Abstract

The deep-sea squid Grimalditeuthis bonplandi has tentacles unique among known squids. The elastic stalk is extremely thin and fragile, whereas the clubs bear no suckers, hooks or photophores. It is unknown whether and how these tentacles are used in prey capture and handling. We present, to our knowledge, the first in situ observations of this species obtained by remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) in the Atlantic and North Pacific. Unexpectedly, G. bonplandi is unable to rapidly extend and retract the tentacle stalk as do other squids, but instead manoeuvres the tentacles by undulation and flapping of the clubs’ trabecular protective membranes. These tentacle club movements superficially resemble the movements of small marine organisms and suggest the possibility that G. bonplandi uses aggressive mimicry by the tentacle clubs to lure prey, which we find to consist of crustaceans and cephalopods. In the darkness of the meso- and bathypelagic zones the flapping and undulatory movements of the tentacle may: (i) stimulate bioluminescence in the surrounding water, (ii) create low-frequency vibrations and/or (iii) produce a hydrodynamic wake. Potential prey of G. bonplandi may be attracted to one or more of these as signals. This singular use of the tentacle adds to the diverse foraging and feeding strategies known in deep-sea cephalopods.

Keywords: bathypelagic, behaviour, Cephalopoda, feeding, luring, mesopelagic

1. Introduction

The deep pelagic comprises the largest, yet least explored, habitat on the Earth [1]. Although cephalopods living in the meso- (200–1000 m) and bathypelagic (1000–4000 m) are diverse and widespread, their natural behaviour and lifestyle are known principally from comparative morphological observations of dead individuals that often have been unintentionally damaged by the nets that collected them. The use of remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and manned submersibles has allowed observations of rarely seen deep-sea squids alive in their natural habitat, and the documentation of their behaviours [2–9].

Most squids have a pair of tentacles that are extendable and retractable through the action of transverse and circular musculature [10]. The tentacle clubs—armed with suckers, hooks or both—are rapidly extended by the tentacles towards food items, and once prey is grasped, they are swiftly retracted into the arm crown for manipulation and consumption [10]. The great variation in squid tentacle morphologies may reflect variation in target prey and the handling of captured food [11]. For example, in the deep-sea species Chiroteuthis calyx, the tentacles, which are supported by the fourth pair of arms, are deployed beneath the squid and are slowly extended and retracted in the vertical plane [4]. The midwater fishes that this species consumes are probably attracted to bioluminescence produced by photophores along the tentacle stalk and club [1].

The meso- and bathypelagic squid Grimalditeuthis bonplandi forms a monotypic genus within the family Chiroteuthidae. Chiroteuthids have slender bodies, with relatively long, thin tentacles. These species are semi-gelatinous and slow-moving, partially as a consequence of ammonium accumulation in extracellular spaces to enhance buoyancy [12]. Members of this family develop through a unique, elongated paralarval stage known as the doratopsis, which features a tail with ‘flotation devices’ or ‘secondary fins’ (misnomer) that vary between species [13]. Like many deep-sea squids, G. bonplandi goes through an ontogenetic descent with increasing maturity, living the majority of its life at depths devoid of sun-derived light [1,14,15]. Although G. bonplandi is infrequently captured, it has a worldwide distribution in tropical, subtropical and temperate seas [16]. This species is consumed by a number of oceanic predators, including lancetfish, tuna [17], blue sharks [18], sperm whales [19,20], swordfish [21] and butterfly kingfish [22].

Grimalditeuthis bonplandi is unique not only within the family Chiroteuthidae, but also among all decapod cephalopods, in that the tentacle club is devoid of suckers, hooks or photophores, and the stalks are extremely thin and easily broken [11]. In fact, descriptions of this species indicated a complete lack of tentacles beyond the doratopsis stage, until the first specimen with an intact tentacle was found in the stomach of a deep-sea fish [11]. It is not known whether G. bonplandi uses the tentacles in prey capture, or if it captures food solely with the arms, as occurs in some oegopsid squids—members of Gonatopsis, Lepidoteuthidae and Octopoteuthidae—that lack tentacles as adults. Using ROVs, we observed seven specimens of G. bonplandi for the first time, to our knowledge, in their natural environment; we collected the second known specimen with an intact tentacle and are able to report on aspects of their unusual tentacle behaviour not observed previously in other squids. In order to explore the possible range of tentacle use by G. bonplandi, tentacle anatomy and prey composition were investigated.

2. Material and methods

(a). In situ observations

On 22 September 2005, we observed and collected a specimen of G. bonplandi with the ROV Tiburon of the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI). This ROV could reach depths of 4000 m, was powered electrically to reduce noise and was equipped with a variable ballast system to attain neutral buoyancy. Four 400-W DeepSea Power and Light HMI lights produced illumination in the daylight range (5500–5600°K). Video was recorded by a broadcast quality Panasonic WVE550 three-chip camera onto Sony Digital Betacam standard definition videocassettes, and a Nikon Coolpix three megapixel camera recorded still images. The squid was collected with a suction device that stored the animal in a 4 l chamber for return to the surface. Prior to capture, we observed and video-recorded the behaviour of the specimen for 22 m 30 s in situ, between 990 and 1015 m depth in the Monterey Submarine Canyon off central California, USA (2500 m above bottom, 36.33° N and 122.89° W, T = 3.99°C, O2 = 0.36 ml l−1).

Between February 2008 and January 2010, six individuals of G. bonplandi were observed and video-taped in the Gulf of Mexico at depths between 914 and 1981 m with ROVs deployed to support offshore oil exploration and production operations. Recordings (one per individual squid) lasted between 14 s and 5 m 41 s. Observational opportunities were provided through a partnership between Louisiana State University, and the oil and gas industry via the Gulf Scientific and Environmental ROV Partnership Using Existing Industrial Technology (SERPENT) project [23]. These specimens were not collected.

(b). Examination of preserved specimens

After collection, the Monterey specimen was preserved and stored in 5% formalin for 7 years prior to measurement. Arm photophores were absent in this specimen. We measured the mantle length (ML), excluding the tail, and the maximum width (Wmax) of the left tentacle stalk of the preserved specimen. Based on the ML, we were able to calculate the length of the extended stalk from still images taken by the ROV (figure 1a). For histological investigation of tentacle musculature, we prepared longitudinal and cross sections of the tentacular stalk and club of G. bonplandi. For comparison, one individual of the closely related C. calyx (ML: 75 mm), whose known habitat overlaps with that of G. bonplandi, was also examined. Chiroteuthis calyx: (i) has many suckers on its tentacle clubs, (ii) deploys the tentacles below its body, (iii) captures midwater fishes, and (iv) has tentacle photophores. Presumably captured fishes are grasped by the suckers on the club, and are retrieved to the arm crown by muscular contraction of the tentacle stalk. A comparison of the morphology between these two species enables us to discuss whether Grimalditeuthis could capture prey in a similar manner.

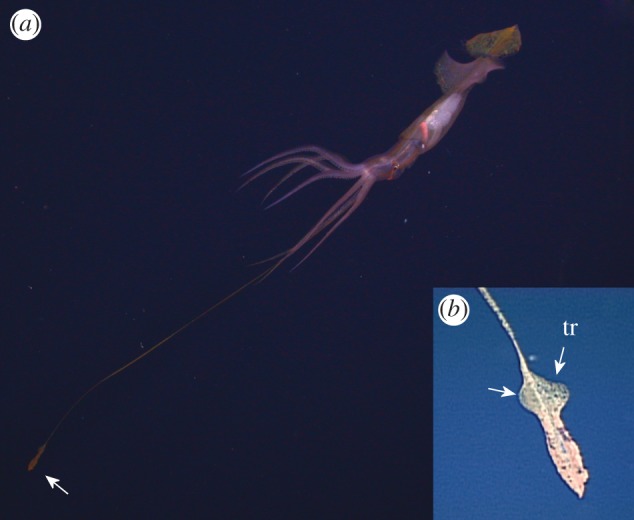

Figure 1.

(a) Grimalditeuthis bonplandi when first observed by the ROV, Monterey Bay at approximately 1000 m. The tentacle club is deployed approximately four mantle lengths anterior to the brachial crown. The chromatophores are expanded to give a mottled coloration, the tail is spread flat and the fourth arm supports the proximal base of the tentacle stalk. (b) Close-up of tentacle club; the trabecular protective membranes (tr) of the club manus, indicated by white arrows, can flap to propel the club.

The tissue samples were dehydrated in a graded ethanol series, cleared with toluene, and embedded in paraffin wax. Cross sections (3 µm thick) were mounted on slides and stained with haemotoxylin and eosin. Additionally, to check for the presence of mucin secreting cells that could have a function in prey adherence, sections of the distal part of the club were stained with mucicarmine stain, with tartrazine as the counter stain.

The stomach contents of 22 specimens of G. bonplandi (ML: 27–150 mm) archived in the collections of the National Museum of Natural History (NMNH), Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC, USA, and seven specimens (75–142 mm) archived in the collections of the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History (SBMNH) were examined and, if present, prey were identified. Digestive tracts were categorized as empty, partially full or full.

3. Results

(a). In situ observations

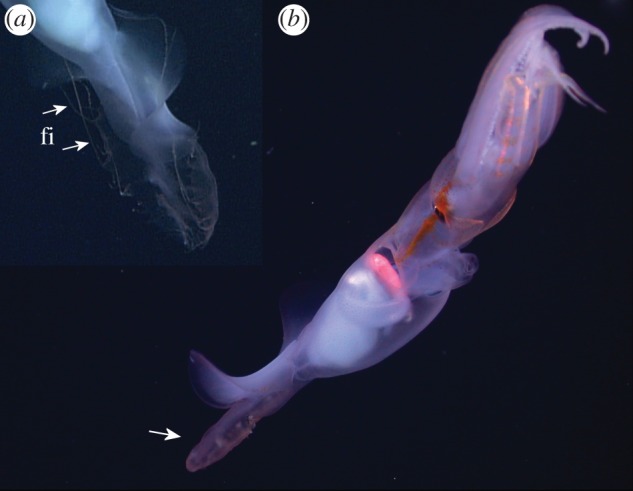

One of the Gulf of Mexico specimens was entrained in thruster wash from the ROV for the entirety of the 14 s observation, and will not be discussed further. Of the remaining six individuals, the body was horizontal upon initial encounter in most instances; however, in one of these, the posterior part of the body was at an angle of approximately 30–40° above horizontal. The entire body of the Monterey specimen was at an angle of 35–40° with the posterior end up (figure 1a). When first observed, all specimens of G. bonplandi were maintaining their position in the water column and were either already gently undulating the fins or began to do so within a few seconds. Posterior to the primary fins, the heart-shaped (distally tapered) tail structure remained spread when individuals were maintaining their position (figure 1a). These tail structures were capable of movement, however, it was limited to either the edges becoming curved inward or the structures rolling into a tube while the animal was swimming or jetting (figure 2). They did not appear to contribute to locomotion. Slender filaments (10–12) of varying length that branched perpendicularly from the margin of each side of the tail structure were observed on the Monterey specimen (figure 2). A few of these filaments, which were capable of extension and retraction, were extended upon initial encounter with the individual, and were often retracted when the animal was disturbed. The translucent skin was scattered with functional yellow–orange chromatophores over the entire body of four specimens, including the Monterey specimen (figures 1 and 2). A prominent stripe of darker, more densely distributed chromatophores occurred on either side of the iris of the latter individual, and extended both anteriorly and posteriorly, from the neck to the brachial pillar (figure 2b). We also observed a hemispherical patch of diffusely iridescent tissue ventral to each eye of the Monterey specimen (figure 2b).

Figure 2.

(a) Close-up of filaments (fi) that can be retracted and extended from the margin of the tail structures. (b) A specimen jetting away rapidly with its tail structure (indicated by a white arrow) curled into a cone, and with expanded chromatophores creating an eye-stripe. The iridescent patches are on the ventral side, one under each eye.

Throughout observations, the arms of all six squid were spread laterally or anterio-laterally while the animal maintained its position. The arms were held straight (n = 6 of six individuals), but were also observed to curve or coil distally (n = 5 of six individuals). The arms of the Monterey specimen were held together while the squid swam (figure 2b). One individual appeared to be missing both the right tentacle club and the right ventral arm. We did not see either tentacle for another of the Gulf of Mexico individuals. Two individuals were observed using the fourth arms to support the tentacle stalk.

Grimalditeuthis bonplandi moved its tentacles away from its body using movements of the tentacle club, and not the tentacle stalk (n = 4 of five individuals in which tentacles were observed). The club movements were of two types: (i) flapping of the trabecular protective membranes (n = 3 of five), and (ii) undulations (n = 3 of five; electronic supplementary material, videos S1 and S2). A trabecular protective membrane (figure 1b) is located along the proximal one-third of each side of the club. These membranes flapped simultaneously in the same direction, which propelled the club and trailing tentacle stalk, distal end first. At other times, the tentacle clubs were observed to undulate, which would propel the club forward or backward, depending on the direction of the undulation. When both tentacles were extended, they could be positioned either parallel to each other or in opposite directions from each other (see the electronic supplementary material, video S2). In order to return the tentacle to the arm crown, the Monterey specimen swam towards the tentacle club, a relatively slow manoeuvre (see the electronic supplementary material, videos S1 and S2). Retrieval of the tentacles by muscular contractions was not observed in any of the other specimens.

(b). Observations of preserved specimens

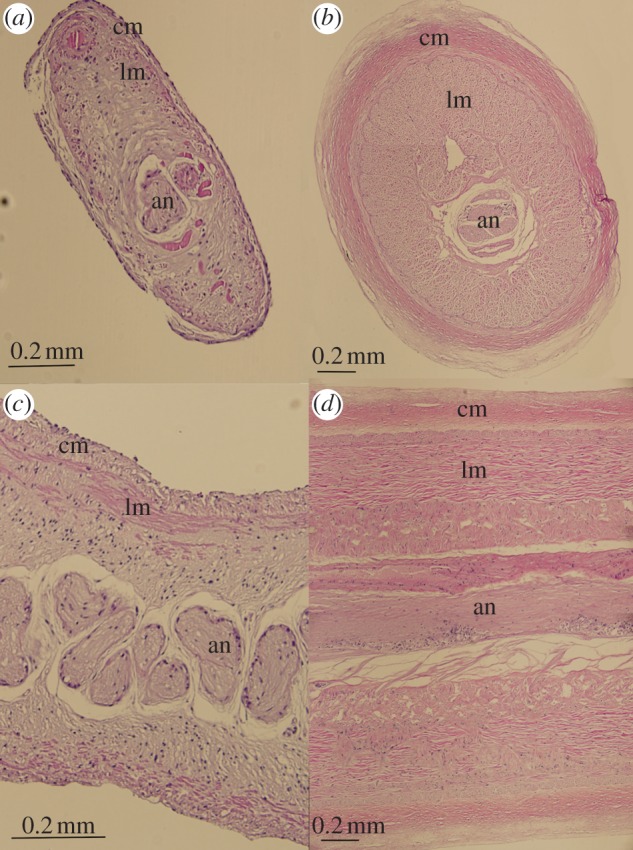

The Monterey specimen was an immature female with an ML of 140 mm. The right tentacle was not observed during the in situ observations, and we confirmed that it was missing from the specimen. The left tentacular stalk of G. bonplandi (Wmax: 1.1 mm) was half as wide as those of the immature female C. calyx examined (Wmax: 2.1 mm). Cross and longitudinal sections through the tentacular stalk of both species show that the circular and longitudinal muscles in the stalks of G. bonplandi are much reduced in comparison with those of C. calyx (figure 3a–d). We confirmed that the G. bonplandi tentacular club lacked secretory cells, suckers, hooks, photophores and a carpal locking apparatus. The oral surface of the tentacular club of G. bonplandi consisted of vacuolated cells and sparse muscles, primarily in the central part of the club. By contrast, the clubs of C. calyx were muscular throughout and contain numerous stalked suckers and a large terminal photophore.

Figure 3.

Histology of Grimalditeuthis bonplandi (a,c) and Chiroteuthis calyx (b,d) tentacles. (a,b) Cross section of tentacle stalk. cm, circular muscle; lm, longitudinal muscle; an, axial nerve. (c,d) Longitudinal section of tentacle stalk, abbreviations as above.

The Monterey specimen had remains of crustaceans in its partially full stomach. Of the 22 NMNH specimens, only 15 were in good enough condition to permit gut content examination. Eight of those 15 had empty digestive tracts, four were partially full and three were full. Two of the seven stomachs containing prey items contained fragments that were possibly from crustaceans, as well as pleopods from a shrimp. The contents of six of these seven specimens included unrecognizable amorphous material. Four stomachs of the SBMNH specimens were empty, one was full with soft tissue but without any hard, identifiable parts and two stomachs contained cephalopod remains (fragments of beaks, sucker rings and suckers, eye lenses, muscle tissue and chitinous hooks).

4. Discussion

We observed G. bonplandi for, to our knowledge, the first time in its natural habitat, and discovered behaviours that shed light on the use of this species’ unique tentacles. Both in situ observations and histological evidence suggest that G. bonplandi lacks the musculature and consequently the ability for rapid muscular extension and retraction of its tentacles, which is key to prey capture in most squids observed thus far. Additionally, the tentacles do not have any hooks, suckers, adhesive pads or photophores that could be used to attract or grasp prey. Instead, flapping of the tentacle clubs’ trabeculate protective membranes or undulation of the club along its length, move the club and trailing tentacle stalk with respect to the squid. These undulatory and flapping movements of the tentacle clubs superficially resemble the swimming of a small midwater animal (e.g. worm, fish, squid, shrimp). We hypothesize that G. bonplandi exploits this resemblance, using the tentacle clubs to attract potential prey towards the squid. How prey is subsequently engulfed by the arms and handled by the suckers remains subject to speculation.

When a predator exploits its resemblance to a non-threatening or inviting object or species to gain access to prey, it is referred to as aggressive mimicry [24–26]. Luring is one form of aggressive mimicry, and there are numerous proposed occurrences of this type of aggressive mimicry in deep-sea organisms. Examples include: the cookie-cutter shark Isistius brasiliensis [27]; anglerfish, viperfish and dragonfish that possess one or more bioluminescent lures [27–29]; the siphonophore Erenna sp. that attracts prey with luminescence and flicking of the modified side-branches of their tentacles (tentilla) [30]; and various squids with photophore-tipped arms or tentacles [2,28].

While all of the above proposed modes of luring are based on bioluminescence, and G. bonplandi does not have photophores, we suggest three ways in which the movements of this species’ tentacle club may exemplify another method of attracting prey in the deep pelagic. First, the club movements may instigate bioluminescence by other organisms in the surrounding water that consequently attract the squids’ potential prey [31]. Second, the club movements create low-frequency vibrations that could be detected by the well-developed mechanoreceptors of deep-sea chaetognaths, crustaceans, fishes and cephalopods [28,32,33]. For example, the long setae on the antennae of copepods are highly sensitive to the movement created by incoming food items. Likewise, sergestid shrimp have a flexible distal portion of their antennae, the flagellum, that allow responses to water vibrations much like the lateral-line system of fishes [28]. Krill may use low-frequency vibrations to aggregate with conspecifics [34,35]. Aggressive mimicry using vibrations has been described in the assassin bug Stenolemus bituberus, which lures spiders by plucking web silk in a way that mimics the spiders’ prey [36]. Finally, the club movements may produce a recognizable hydrodynamic signal that potential prey would follow because it resembled a signal produced by its own prey or a mate. The ability of marine organisms to detect and follow hydrodynamic signals is probably common, and has been reported for copepods such as male Temora longicornis, looking for mates, and the harbour seal Phoca vitulina tracking prey trails minutes after swimming has ceased [37,38].

Lures may, in some cases, bear a high resemblance to their models (e.g. when exploiting sexual signals). However, other aggressive mimics do not directly resemble the appearance of models. In these cases, the mimics resemble a broader class of models rather than a specific one; or the lure may exhibit a stronger signal than the model, provoking a more intense response from the prey [36].

Although there is no undisputed example of a cephalopod using a lure [39], there are several examples of both shallow and deep-dwelling species that are hypothesized to do so. Angling has been speculated for the sepiolid Rossia pacifica [40], which burrows into sand but sticks out one arm which is then wiggled irregularly. The loliginid squid Sepioteuthis sepioidea [41] and the cuttlefishes Sepia officinalis and Sepia latimanus [39] wave their dorsal arm pairs from side to side before attacking prey, which may indicate hypnotizing or luring. As mentioned above, the mesopelagic squid C. calyx presumably uses bioluminescence to attract prey with its tentacular photophores [1]. Octopoteuthis deletron is believed to use its photophores, which are present on all arm tips, to attract prey and they have been observed wiggling one or two arm tips [2]. To this range of cephalopods that are hypothesized to use a lure to attract prey (i.e. aggressive mimicry), we can now add G. bonplandi.

The singular use of G. bonplandi’s tentacle reported here expands the known diversity of cephalopod feeding strategies and advances the discovery of unique behaviours that have evolved in cephalopods inhabiting the largest living space on our ocean planet.

Acknowledgements

We thank the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) and the Royal Dutch Academy of Science (KNAW). We also thank the staff of MBARI's videolab and the pilots of the ROV Tiburon and ships’ crew of the R/V Western Flyer, as this study would not have been possible without their efforts. Richard Young is thanked for his comments on an early draft of this paper. The Community Hospital of the Monterey Peninsula is thanked for the preparation of histological sections. We thank the ROV teams from Saipem-America and Oceaneering who provided the observations. Eric Hochberg from the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History kindly assisted with access to the museum specimens.

Funding statement

Gulf SERPENT is supported by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) with matching funds from BP and Shell. The David and Lucile Packard Foundation, the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research and the Royal Dutch Academy for Sciences (KNAW) part funded the research.

References

- 1.Robison BH. 2004. Deep pelagic biology. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 300, 253–272 (doi:10.1016/j.jembe.2004.01.012) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bush SL, Robison BH, Caldwell RL. 2009. Behaving in the dark: locomotor, chromatic, postural, and bioluminescent behaviors of the deep-sea squid Octopoteuthis deletron Young 1972. Biol. Bull. 216, 7–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoving HJT, Bush SL, Robison BH. 2012. A shot in the dark: same-sex sexual behaviour in a deep-sea squid. Biol. Lett. 8, 287–290 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2011.0680) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hunt JC. 1996. The behavior and ecology of midwater cephalopods from Monterey Bay: submersible and laboratory observations. PhD thesis, University of California, Los Angeles [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunt JC, Seibel BA. 2000. Life history of Gonatus onyx (Cephalopoda: Teuthoidea): ontogenetic changes in habitat, behavior and physiology. Mar. Biol. 136, 543–552 (doi:10.1007/s002270050714) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robison BH, Reisenbichler KR, Hunt JC, Haddock SHD. 2003. Light production by the arm tips of the deep-sea cephalopod Vampyroteuthis infernalis. Biol. Bull. 205, 102–109 (doi:10.2307/1543231) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roper CFE, Vecchione M. 1996. In situ observations on Brachioteuthis beanii (Verrill): paired behavior, probably mating (Cephalopoda, Oegopsida). Am. Malacol. Bull. 13, 55–60 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seibel BA, Robison BH, Haddock SHD. 2005. Post spawning egg-care by a squid. Nature 438, 929 (doi:10.1038/438929a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vecchione M, Roper CFE, Widder EA, Frank TM. 2002. In situ observations on three species of large-finned squids. Bull. Mar. Sci. 71, 893–901 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kier WM. 1982. The functional-morphology of the musculature of squid (Loliginidae) arms and tentacles. J. Morphol. 172, 179–192 (doi:10.1002/jmor.1051720205) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young RE, Vecchione M, Donovan DT. 1998. The evolution of coleoid cephalopods and their present biodiversity and ecology. S. Afr. J. Mar. Sci. 20, 393–420 (doi:10.2989/025776198784126287) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seibel BA, Goffredib SK, Theusen EV, Childress JJ, Robison BH. 2004. Ammonium content and buoyancy in midwater cephalopods. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 313, 375–387 (doi:10.1016/j.jembe.2004.08.015) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vecchione M, Robison BH, Roper CFE. 1992. A tale of two species: tail morphology in paralarval Chiroteuthis. Proc. Biol. Soc. Wash. 105, 683–692 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roper CFE, Young RE. 1975. Vertical distribution of pelagic cephalopods. Smith. Contrib. Zool. 209, 1–51 (doi:10.5479/si.00810282.209) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young RE. 1972. The systematics and areal distribution of pelagic cephalopods from the seas off southern California. Smith. Contrib. Zool 97, 1–159 (doi:10.5479/si.00810282.97) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jereb P, Roper CFE. 2010. Cephalopods of the World: an annotated and illustrated catalogue of cephalopod species known to date. FAO Species Catalogue for Fishery Purposes No. 4, vol. 2. Rome, FAO. 605 p

- 17.Potier M, Marsac F, Cherel Y, Lucas V, Sabatie R, Maury O, Menard F. 2007. Forage fauna in the diet of three large pelagic fishes (lancetfish, swordfish and yellowfin tuna) in the western equatorial Indian Ocean. Fish. Res. 83, 60–72 (doi:10.1016/j.fishres.2006.08.020) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Markaida U, Sosa-Nishizaki O. 2010. Food and feeding habits of the blue shark Prionace glauca caught off Ensenada, Baja California, Mexico, with a review on its feeding. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 90, 977–994 (doi:10.1017/S0025315409991597) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clarke MR. 1980. Cephalopoda in the diet of sperm whales of the southern hemisphere and their bearing on sperm whale biology. Disc. Rep. 37, 1–324 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clarke MR. 1996. Cephalopods in the World's oceans: cephalopods as prey. III. Cetaceans. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 351, 1053–1065 (doi:10.1098/rstb.1996.0093) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Markaida U, Hochberg FG. 2005. Cephalopods in the diet of swordfish Xiphias gladius Linnaeus caught off the west coast of Baja California, Mexico. Pac. Sci. 59, 25–41 (doi:10.1353/psc.2005.0011) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsuchiya K, Sawadaishi S. 1997. Cephalopods eaten by the butterfly kingfish Gasterochisma melapus in the eastern South Pacific Ocean. Venus (Tokyo) 56, 49–59 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benfield MC, Graham WM. 2010. In situ observations of Stygiomedusa gigantea in the Gulf of Mexico with a review of its global distribution and habitat. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 90, 1079–1093 (doi:10.1017/S0025315410000536) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stevens M. 2013. Sensory ecology, behaviour, and evolution. Glasgow, UK: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wickler W. 1965. Mimicry and evolution of animal communication. Nature 208, 519 (doi:10.1038/208519a0) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wickler W. 1968. Mimicry in plants and animals. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill [Google Scholar]

- 27.Widder EA. 1998. A predatory use of counterillumination by the squaloid shark, Isistius brasiliensis. Environ. Biol. Fish. 53, 267–273 (doi:10.1023/A:1007498915860) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herring PJ. 2002. The biology of the deep ocean. Oxford, UK: University Press [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miya M, et al. 2010. Evolutionary history of anglerfishes (Teleostei: Lophiiformes): a mitogenomic perspective. BMC Evol. Biol. 10, 1–27 (doi:10.1186/1471-2148-10-58) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haddock SHD, Dunn CW, Pugh PR, Schnitzler CE. 2005. Bioluminescent and red-fluorescent lures in a deep-sea siphonophore. Science 309, 263 (doi:10.1126/science.1110441) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haddock SHD, Moline MA, Case JF. 2010. Bioluminescence in the sea. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2, 443–493 (doi:10.1146/annurev-marine-120308-081028) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Büdelmann BU. 1994. Cephalopod sense organs, nerves and the brain: adaptations for high performance and life style. Mar. Freshw. Behav. Phys. 25, 13–33 (doi:10.1080/10236249409378905) [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marshall NB. 1979. Developments in deep-sea biology. Poole, UK: Blandford Press [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bleckmann H, Breithaupt T, Blickhan R, Tautz J. 1991. The time course and frequency content of hydrodynamic events caused by moving fish, frogs, and crustaceans. J. Comp. Phys. A, Sens. Neural Behav. Physiol. 168, 749–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wiese K, Ebina Y. 1995. The propulsion jet of Euphausia superba (Antarctic krill) as a potential communication signal among conspecifics. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 75, 43–54 (doi:10.1017/S0025315400015186) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wignall AE, Taylor PW. 2011. Assassin bug uses aggressive mimicry to lure spider prey. Proc. R. Soc. B 278, 1427–1433 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.2060) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Doall MH, Colin SP, Strickler JR, Yen J. 1998. Locating a mate in 3D: the case of Temora longicornis. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 353, 681–689 (doi:10.1098/rstb.1998.0234) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dehnhardt G, Mauck B, Hanke W, Bleckmann H. 2001. Hydrodynamic trail-following in harbor seals (Phoca vitulina). Science 293, 102–104 (doi:10.1126/science.1060514) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hanlon RT, Messenger JB. 1996. Cephalopod behavior. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anderson RC, Mather JA, Steele CW. 2004. Burying and associated behaviors of Rossia pacifica (Cephalopoda : Sepiolidae). Vie et Milieu Life Environ. 54, 13–19 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moynihan M, Radoniche AF. 1982. The behavior and natural history of the Caribbean reef squid Sepioteuthis sepiodea. With a consideration of social, signal and defensive patterns for difficult and dangerous environments. Adv. Ethol. 25, 1–151 [Google Scholar]