Abstract

Cellulosimicrobium cellulans is one of the microorganisms that produces a wide variety of yeast cell wall-degrading enzymes, β-1,3-glucanase, protease and chitinase. Dried cells of Saccharomyces cerevisiae were used as carbon and nitrogen source for cell growth and protease production. The medium components KH2PO4, KOH and dried yeast cells showed a significant effect (p<0.05) on the factorial fractional design. A second design was prepared using two factors: pH and percentage of dried yeast cells. The results showed that the culture medium for the maximum production of protease was 0.2 g/l of MgSO4.7H2O, 2.0 g/l of (NH4)2SO4 and 8% of dried yeast cells in 0.15M phosphate buffer at pH 8.0. The maximum alkaline protease production was 7.0 ± 0.27 U/ml over the center point. Crude protease showed best activity at 50ºC and pH 7.0-8.0, and was stable at 50ºC.

Keywords: response surface, medium optimization, alkaline protease, Cellulosimicrobium cellulans, actinomycete

INTRODUCTION

Actinomycetes, a Gram-positive mycelium forming bacterial group, are able degrade macromolecules, being efficient in the breakdown of proteins (25). The microbiology of Brazilian soil, which has special environmental characteristics and is rich in actinomycete populations, has not been very well explored and constituting an excellent source for the search for new enzymes (5). C. cellulans is an actinomycete that was isolated from residues of an alcohol fermentation industry. This microorganism produces an extracellular enzyme complex during growth, which consists mainly of β-1,3-glucanase, chitinase and alkaline protease. This enzyme complex is capable of lysing yeast cell walls.

Proteases are probably the most important class of enzymes, which constitute about 65% of the total industrial enzyme market (13). Proteases have applications in various industries such as the detergent, food, pharmaceutical, leather and silk industries (22). In recent years the use of alkaline protease as an industrial catalyst has increased. These enzymes exhibit high catalytic activity and are economically feasible. Various physiological activities have been detected in the hydrolysates derived from the proteolytic hydrolysis of many food proteins. For example, antioxidative peptides were isolated from a hydrolysate prepared with microbial protease (4).

The optimization of culture medium components for alkaline protease production by microorganisms, mainly Bacillus, was presented in several recent articles (3,13,15,17,23). Some of these components were glucose, corn starch, yeast extract, corn steep liquor, sucrose, casein, malt extract, polypeptone, fructose corn syrup, maltose, potato starch, molasses, whey, soybean meal and several salts. The aim of these papers was increase the protease production and the cellular growth.

The cost of enzyme production is a major obstacle in its successful industrial application. Statistical approaches offer ideal ways for process optimization studies in biotechnology, and have advantages because they use the fundamental principles of statistics, randomization and replication (13). In view of the promising applicability of the alkaline protease, it should be produced in high yields in a low-cost medium. Within this context, the purpose of the present study was to determine the optimum culture medium and the best fermentation conditions for the maximum protease production from Cellulosimicrobium cellulans, as well as to partially characterize the crude enzyme.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Microorganism

The culture of C. cellulans was isolated from alcohol fermentation industrial waste in the Food Biochemistry Laboratory, UNICAMP, and identified by the Korean Institute of Bioscience & Biotechnology.

Protease Production

Protease production from C. cellulans was carried out in 50 ml of sterile medium containing 13.6 g/l of KH2PO4, 2.0 g/l of (NH4)2SO4, 4.2 g/l of KOH, 0.2 g/l of MgSO4.7H2O, 0.001 g/l of Fe2(SO4)3.6H2O, 1 mg/l of thiamine, 1 mg/l of biotin and 1% of dried S. cerevisiae cells (20, with modification). Initial pH of the culture medium was 7.5. The culture medium was inoculated with a 10% inoculum of a 15 hour culture of C. cellulans and incubated at 30ºC with shaking (150 rpm) for 24 hours. The culture was centrifuged at 10000g for 10 minutes at 5ºC. Protease activity of the supernatant was determined.

Protease assay

The protease was assayed by Obata et al. (12) using casein as substrate. One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of protease required to produce an increase in absorbance of 1.0 in 30 minutes (18) under the above assay conditions.

Identification of important nutrient components of the culture medium (fractional design)

A factorial design was used to estimate the effects of each medium component on enzyme production. Initially, eight components of the culture medium were studied. To screen the relative influence of these factors and their possible interactions in the experimental domain, a 28-3 fractional factorial design was chosen. The assays were performed at 30ºC with agitation of 150 rpm. Table 1 presents the 35 assays performed and the respective concentrations of the culture medium components.

Table 1.

Design matrix for the 28-3 fractional factorial design and the response after analysis.

| Run | KH2PO4 | (NH4)2SO4 | KOH | MgSO4.7H2O | Fe(SO4)3.6H2O | Thiamine | Biotin | yeast cells | Protease Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g/l | 10-3 g/l | % | U/ml | ||||||

| 1 | 19.6 | 3.0 | 6.4 | 0.3 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 0.27 |

| 2 | 19.6 | 3.0 | 6.4 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 0.10 |

| 3 | 19.6 | 3.0 | 6.4 | 0.1 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.10 |

| 4 | 19.6 | 3.0 | 6.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 0.23 |

| 5 | 19.6 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 0.3 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 0.06 |

| 6 | 19.6 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 0.15 |

| 7 | 19.6 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 0.21 |

| 8 | 19.6 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.07 |

| 9 | 19.6 | 1.0 | 6.4 | 0.3 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.07 |

| 10 | 19.6 | 1.0 | 6.4 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 0.24 |

| 11 | 19.6 | 1.0 | 6.4 | 0.1 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 0.20 |

| 12 | 19.6 | 1.0 | 6.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 0.09 |

| 13 | 19.6 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.3 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 0.12 |

| 14 | 19.6 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.09 |

| 15 | 19.6 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 0.08 |

| 16 | 19.6 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 0.15 |

| 17 | 7.6 | 3.0 | 6.4 | 0.3 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 0.54 |

| 18 | 7.6 | 3.0 | 6.4 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.19 |

| 19 | 7.6 | 3.0 | 6.4 | 0.1 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 0.28 |

| 20 | 7.6 | 3.0 | 6.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 0.55 |

| 21 | 7.6 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 0.3 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | .0.08 |

| 22 | 7.6 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 0.09 |

| 23 | 7.6 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 0.09 |

| 24 | 7.6 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 0.03 |

| 25 | 7.6 | 1.0 | 6.4 | 0.3 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 0.24 |

| 26 | 7.6 | 1.0 | 6.4 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 0.23 |

| 27 | 7.6 | 1.0 | 6.4 | 0.1 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 0.65 |

| 28 | 7.6 | 1.0 | 6.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.18 |

| 29 | 7.6 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.3 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 0.03 |

| 30 | 7.6 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 0.09 |

| 31 | 7.6 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.07 |

| 32 | 7.6 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 0.12 |

| 33* | 13.6 | 2.0 | 4.2 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.19 |

| 34* | 13.6 | 2.0 | 4.2 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.18 |

| 35* | 13.6 | 2.0 | 4.2 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.23 |

center point

Central composite experimental design to optimize the medium components

A new design was prepared using two factors: pH and concentration of dried yeast cells. We used a central composite design to find the optimal concentration of two factors. For this purpose, a set of 11 experiments including 22 factorial experiments, three center point and four axial points (α = 1.41) were conducted. The assays were performed at 30ºC with agitation of 150 rpm. The setting range for factors was as follows: pH, 6.6-9.4 and percentage of dried yeast cells, 4.0-11.0%.

A multiple regression analysis of the data was carried out with the statistical package (Statistica 5.0) and the second-order polynomial equation was obtained: y = a0 + a1.x1 + a2.x2 +a3.x12 + a4.x22 + a5.x1.x2; where a0 is the intercept term; a1, a2 are linear coefficients; a3, a4 are squared coefficients and a5 is the interaction coefficient.

Central composite design to optimize the fermentation conditions

An experimental design was prepared to evaluate the optimal temperature and agitation conditions for maximum protease production. The range studied in this experimental design was from 18 to 32ºC for the temperature and from 80 to 220 rpm for the agitation speed. Once the response was obtained, the data were correlated as second-order polynomial models.

The relationships between responses and variables were determined using the software Statistica ® 5.0 from Statsoft Inc. (2325 East 13 th Street, Tulsa, OK, 74104, USA). The response surface graph indicates the effect of variables and determines their optimum levels for maximal protease production.

Protease production and kinetic of growth in the optimized culture medium

One loopfull of a 24 hour culture of C. cellulans was inoculated in 10ml of the optimized culture medium and incubated at 27ºC for 16 hours at 150 rpm. Five ml of this culture were transferred to 250 ml Erlenmeyer flasks containing 45 ml of the same culture medium, and incubated at 27ºC at 150 rpm. One ml samples were collected after 5, 10, 24, 48 and 72 hours of growth. The samples were transferred to tubes containing 9 ml of a 0.2% Tween 80 solution and mixed vigorously in a vortex for 5 minutes. The viable cell count was performed using serial dilutions on TYM agar plates, incubated at 30ºC. The number of colony forming units was determined by the drop method (9).

Crude enzyme characterization

To investigate the effect of temperature on protease activity, the protease assay was performed in the temperature range from 20 to 96ºC at pH 7.5. The influence of pH was investigated using 50 mM buffer solutions ranging from 2.6 to 10.7, at the optimum temperature previously determined. To determine the enzyme stability, the crude enzyme was incubated at temperatures ranging from 5 to 80ºC in a 50 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.5. After 15 minutes incubation, the reaction mixture was assayed, and the residual enzymatic activity was measured. The crude enzyme was incubated at pH ranging from 2.6 to 10.7 at 30ºC during 1 hour, and then the residual enzymatic activity was determined.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Factorial fractional design (28-3) to estimate the effects of the culture medium components on protease production.

Table 1 show the factorial fractional design matrix and Table 2 shows the main effects in the fractional experimental design. The culture medium components that showed significant effects (p<0.05) on protease production were KH2PO4, KOH and dried yeast cells. The effect of KH2PO4 was -0.077. The negative effect indicates that an increase in the concentration of this compound (level -1 to level +1) in the culture medium resulted in 0.077 U/ml less protease activity; this represents a reduction of 35.6% (0.216 to 0.139 U/ml) in the protease activity. The effects of KOH and dried yeast cells were 0.164 and 0.128. Thus, the increase in these variables from level -1 to level +1 resulted in an increase of 170.8% (0.096 to 0.260 U/ml) and 112.3% (0.114 to 0.242) in the protease activity, respectively.

Table 2.

Main effects of the variables on protease production (28-3 fractional design).

| Factor | Effect | p |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | 0.180* | 0.001* |

| KH2PO4 | -0.077* | 0.014* |

| (NH4)2SO4 | 0.024 | 0.121 |

| KOH | 0.164* | 0.003* |

| MgSO4.7H2O | -0.032 | 0.076 |

| Fe(SO4)3.6H2O | 0.031 | 0.0820 |

| Thiamine | -0.014 | 0.264 |

| Biotin | -0.026 | 0.111 |

| Dried yeast cells | 0.128* | 0.005* |

Statistically significant values (p < 0.05).

The effects of thiamine, biotin and Fe2(SO4)3.6H2O were not significant (p>0.05), meaning that they were not necessary for protease production since that the lowest studied level for they was concentration zero.

The effect of MgSO4.7H2O and (NH4)2SO4 were also not significant in the studied levels, however, they were kept at the concentration used in the initial medium, 0.2 and 2.0 g/l respectively, because they were not studied at concentration zero.

KH2PO4 and KOH showed a significant effect. The significant role of phosphate ions in protease production is in agreement with others reports (10). These compounds are also related to the pH of the culture medium, thus the influence of pH on protease production was evaluated in a new experimental design.

Central composite design to optimize the medium components

More two experimental designs were performed after the first design. They showed that the protease production increased when pH and the percentage of dried yeast cells increased. Based in these results, the levels studied in the design presented in Table 3 were defined.

Table 3.

Results obtained in the central composite design for culture medium optimization.

| Experiment | pH | % Dried yeast cells | Protease activity (U/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9.0 | 10.0 | 4.94 |

| 2 | 9.0 | 5.0 | 2.42 |

| 3 | 7.0 | 10.0 | 4.30 |

| 4 | 7.0 | 5.0 | 3.88 |

| 5 | 9.4 | 7.5 | 3.98 |

| 6 | 6.6 | 7.5 | 5.42 |

| 7 | 8.0 | 11.0 | 5.82 |

| 8 | 8.0 | 4.0 | 3.36 |

| 9* | 8.0 | 7.5 | 7.18 |

| 10* | 8.0 | 7.5 | 6.88 |

| 11* | 8.0 | 7.5 | 7.42 |

center point.

C. cellulans produced 0.20 ± 0.03 U/ml protease with the initial medium. Table 3 shows the central composite design matrix.

Protease activity around the center points was 7.16 ± 0.27 U/ml. The Analysis of Variance of the optimization study showed that the model-F value was 15.04. This value is more than three times the value of F3,7 value (4.35), indicating that the quadratic model has a good fit.

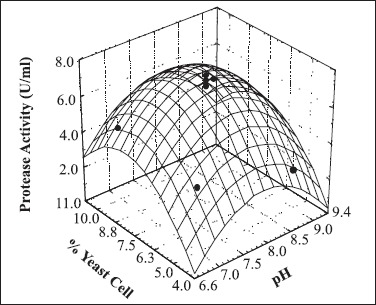

Fig. 1 shows the estimated response surface for protease production based on two statistically significant factors. The highest protease production was observed when the value of the culture medium pH was between 7.5 and 8.5, and the dried yeast cell concentration between 7.0 and 9.0%.

Figure 1.

Response surface curve of protease production (U/ml) by C. cellulans as a function of dried yeast cell percentage and pH. Protease activity (U/ml) = 7.16 - 1.42 pH2 + 0.80 DYC - 1.48 DYC2, where pH is the value of the coded pH and DYC, the value of the coded percentage of dried yeast cell.

The regression equation obtained from the analysis of variance (ANOVA) indicated that the R2 value (correlation coefficient) is 0.86 (a value > 0.75 indicates aptness of the model). This value ensured a satisfactory adjustment of the quadratic model to the experimental data and indicated that 86% of the variability in the response could be explained by the model.

The culture medium for maximum protease production was 0.2 g/l of MgSO4.7H2O, 2.0 g/l of (NH4)2SO4 and 8.0% of dried yeast cells in 0.15M phosphate buffer pH 8.0.

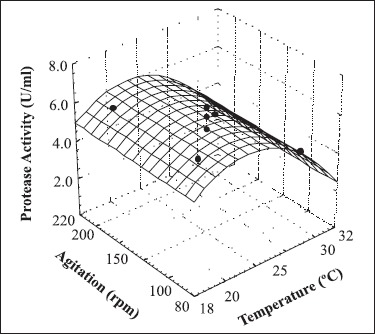

Central composite design to optimize the fermentation conditions

Table 4 shows the central composite design matrix. Optimization of the fermentation conditions presented an increase of about 16% in protease activity (8.28 ± 0.29 U/ml). The analysis of variance showed that the variation in agitation speed during microbial growth did not significantly affect protease production. Enzyme production was only influenced by fermentation temperature, showing a significant effect of - 1.13 on protease production.

Table 4.

Results of the runs of the central composite design for optimization of the fermentation conditions.

| Run | Temperature (°C) | Agitation (rpm) | Protease Activity (U/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30 | 200 | 7.14 |

| 2 | 30 | 100 | 7.52 |

| 3 | 20 | 200 | 8.42 |

| 4 | 20 | 100 | 8.50 |

| 5 | 18 | 150 | 7.80 |

| 6 | 32 | 150 | 6.90 |

| 7 | 25 | 80 | 8.59 |

| 8 | 25 | 220 | 8.89 |

| 9* | 25 | 150 | 8.55 |

| 10* | 25 | 150 | 7.98 |

| 11* | 25 | 150 | 8.31 |

center point.

The analysis of variance showed that the statistical coded model was significant and predictive. The model-F value (21.87) was 7 times higher than the F2,8 value (3.11) and the R2 value was 0.84 (p<0.10).

The response surface presented in Fig. 2 indicates that the highest protease activity was observed when the fermentation was performed at temperatures between 20 and 27ºC.

Figure 2.

Response surface curve of protease production as a function of temperature and agitation speed. Protease activity (U/ml) = 8.46 - 0.44 T - 0.56 T2, where T is the coded value for the temperature.

Culture medium optimization produced an increase of about 36 times in protease activity when compared with the activity in the initial culture medium (0.20 ± 0.03 U/ml, 7.16 ± 0.27 U/ml), optimization of the fermentation conditions presented an increase of about 16% (7.16 ± 0.27 U/ml, 8.28 ± 0.29 U/ml).

There is a growing acceptance of use of statistical experimental designs in biotechnology. Many scientists have reported satisfactory optimization of protease production from microbial sources using the statistical approach (7,16,24). In this study, response surface methodology was shown to be efficient for the optimization of the enzyme production.

In view of the commercial utility of the enzyme, a cost-effective media formulation becomes a primary concern (3). Protease production by C. cellulans in the initial medium was very low. Optimization of this culture medium showed that is possible to increase protease production and reduce the cost of the culture medium with the use of yeast cells. Yeast cells are a residue of the alcohol fermentation industry and are a rich source of carbon and nitrogen for the cellular growth and alkaline protease production. The use of the yeast cell wall was only possible because C. cellulans is a yeast lysing microorganism (YLM) and it is capable of using the cell walls of yeasts as source of nutrients. Moreover, this culture medium is hardly contaminated by nonlytic microorganisms.

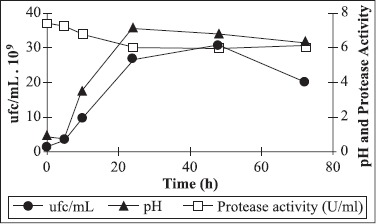

Protease production and kinetic of growth in the optimized culture medium

Protease was produced during the exponential growth phase (Fig. 3). Protease activity was detected from the early stages in the culture medium, showing that the yeast cell was an excellent nutrients source. The activity increased greatly during the exponential growth phase, reaching a plateau during the stationary phase. Maximum alkaline protease production was observed after 24 hours of incubation.

Figure 3.

Kinetics of growth and protease production by C. cellulans in the optimized culture medium.

Maximum protease production was observed after 24 hours of fermentation, when the stationary phase of microbial growth begins. Protease production was shown to be directly related to biomass production as reported by Puri et al. (16) and Chauhan and Gupta (3). Azeredo et al. (2) and Chauhan et al. (3) reported maximum protease production by Bacillus sp. after 96 hours of incubation. Thys et al. (24) reported maximum enzyme production by Microbacterium sp upon 48-96 h of incubation. The decline in protease production in prolonged incubation may be due to autolysis or the proteolytic activity of other proteases (3).

Protease properties in crude extract

The maximum activity was observed at 50ºC. Thermophilic proteases from Actinomycetes, with high activity at 70ºC, have been reported for Thermoactinomyces vulgaris (7) and Streptomyces thermovulgaris (26). The strain of actinomycete Arthrobacter sp presented high activity at 55ºC (1). Alkaline proteases from Bacillus sp. presented optimum temperature about 55 to 70ºC (11,14,21).

The optimum pH of proteolytic activity was found to be 7.0-8.0, but significant levels of activity (80%) were still detected between pH 8.0 and 10.7. There are reports of alkaline proteases from Bacillus sp. that presents the maximum activity at pH 8.0 to 9.0 (8,11,21). Proteases from Actinomycetes Arthrobacter luteus, Arthrobacter sp and Oerskovia xanthineolytica presented high activity at pH 10.5, 11.0 and 9.5-11.0, respectively (1,6,19).

C. cellulans protease was stable (around 90% of activity) in a range of temperature from 5 to 55ºC after 15 minutes incubation. At low temperatures (-5ºC), the crude enzyme preparation retained 96.8% of its activity after 2 months. The enzyme was stable between pH 7.0 and 9.0 after 1 hour of incubation.

C. cellulans is a very promising strain for biotechnological application. The alkaline protease of this microorganism was produced in a low cost medium, providing a novel and effective alternative for the production of a higher value product.

RESUMO

Produção de protease alcalina por Cellulosimicrobium cellulans

Cellulosimicrobium cellulans é um microrganismo que produz uma variedade de enzimas que hidrolisam a parede celular de leveduras: β-1,3-glucanase, protease e quitinase. Células desidratadas de Saccharomyces cerevisiae foram usadas como fonte de carbono e nitrogênio para o crescimento celular e produção de protease. Os componentes do meio de cultura: KH2PO4, KOH e células de levedura desidratadas mostraram efeitos significativos (p<0,05) no planejamento experimental fracionário. Um segundo planejamento foi preparado usando dois fatores: pH e porcentagem de células de levedura desidratadas. Os resultados mostraram que o meio de cultura para a produção máxima de protease foi 0,2 g/L de MgSO4.7H2O; 2,0 g/L de (NH4)2SO4 e 8% de células de levedura desidratadas em tampão fosfato 0,15M e pH 8,0. A produção máxima de protease alcalina foi 7,0 ± 0,27 U/mL no ponto central. A protease bruta apresentou atividade ótima a 50ºC e pH 7,0-8,0; e foi estável a 50ºC.

Palavras-chave: superfície de resposta, otimização de meio, protease alcalina, Cellulosimicrobium cellulans, actinomiceto.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adamistsch B.F., Karner F., Hampel W. Proteolytic of a yeast cell wall lytic Arthrobacter species. Lett. App. Microbiol. 2003;36(4):227–229. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.2003.01300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azeredo L.A.I., Freire D.M.G., Soares R.M.A., Leite S.G.F., Coelho R.R.R. Production and partial characterization of thermophilic proteases from Streptomyces sp. isolated from Brazilian cerrado soil. Enzyme Microbial Technol. 2004;34:354–358. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chauhan B., Gupta R. Application of statistical experimental design for optimization of alkaline protease production from Bacillus sp. RGR-14. Process Biochem. 2004;39:2115–2122. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen H.M., Muramoto K., Yamauchi F. Structural analysis of antioxidative peptides from soybean. J. Agricul. Food Chem. 1995;43:574–78. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coelho R.R.R., Drozdowicz A. The occurrence of Actinomycetes in a cerrado soil in Brazil. Ver. Ecol. Sol. 1978;15:459–473. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Funatsu M., Oh H., Aizono Y., Shimoda T. Protease of Arthrobacter luteus, properties and function on lysis of viable yeast cells. Agricul. Biol. Chem. 1978;42:1975–1977. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta R., Beg Q.K., Lorentz P. Bacterial alkaline proteases molecular approaches and industrial applications. App. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2002;59:15–32. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-0975-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joshi G.K., Kumar S., Sharma V. Production of moderately halotolerant SDS stable alkaline protease from Bacillus cereus MTCC 6840 isolated from lake Nainitial, Uttaranchal state, India. Braz. J. Miocrobiol. 2007;38:773–779. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miles A.A., Misra S.S. The estimation of the bactericidal power of blood. J. Hygiene. 1938;38:732–749. doi: 10.1017/s002217240001158x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moon S-H., Parulekar S.J. Parametric study of protein production in batch and bath cultures of Bacillus firmus. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1991;37:467–483. doi: 10.1002/bit.260370509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nascimento W.C.A., Martins M.L.L. Production and properties of an extracellular protease from thermophilic Bacillus sp. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2004;35:91–96. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Obata T., Iwata H., Namba Y. Proteolytic enzyme from Oerskovia sp CK lysing viable yeast cell. Agricul. Biol. Chem. 1977;41:2387–2394. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oskouie S.F.G., Tabandeh F., Yakhchali B., Eftekhar F. Response surface optimization of medium composition for alkaline protease production by Baccillus clausii. Biochem. Engineer. J. 2008;39:37–42. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel R.K., Dodia M.S., Joshi R.H., Singh S.P. Purification and characterization of alkaline protease from a newly isolated haloalkalophilic Bacillus sp. Process Biochem. 2006;41:2002–2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Potumarthi R., Subhakar C., Jetty A. Alkaline protease production by submerged fermentation in stirred tank reactor using Bacillus licheniformis NCIM-2042: Effect of aeration and agitation regimes. Biochem. Eng. J. 2007;34:185–192. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Puri S., Beg Q.K., Gupta R.G. Optimization of alkaline protease production from Bacillus sp. using response surface methodology. Curr. Microbiol. 2002;44:286–290. doi: 10.1007/s00284-001-0006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reddy L.V.A., Wee Y-J., Yun J-S., Ryu H-W. Optimization of alkaline protease production by batch culture of Bacillus sp RKY3 through Plackett-Burman and response surface methodology approaches. Bioresour. Technol. 2008;99:2242–2249. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rowley B.I., Bull A.T. Isolation of a yeast-lysing Arthrobacter species and the production of the lytic enzyme complex in batch and continuous-flow fermentors. Biotec. Bioeng. 1977;19:879–899. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saeki K., Iwata J., Watanabe Y., Tamai Y. Purification and characterization of an alkaline protease from Oerskovia xanthineolytica TK-1. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 1994;77(5):554–556. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scoot J.H., Schekman R. Lyticase: endoglucanase and protease activities that act together in yeast cell lysis. J Bacteriol. 1980;142:414–423. doi: 10.1128/jb.142.2.414-423.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silva C.R., Delatorre A.B., Martins M.L.L. Effect of the conditions on the production of an extracellular protease by thermophilic Bacillus sp and some properties of the enzymatic activity. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2007;38:253–258. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh J., Batra N., Sobti R.C. Serine alkaline protease from a newly isolated Bacillus sp. SSR1. Process Biochem. 2001;36:781–85. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tari C., Genckal H., TokatlÝ F. Optimization of a growth medium using a statistical approach for the production of an alkaline protease from a newly isolated Bacillus sp. L21. Process Biochem. 2006;41:659–665. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thys R.C.S., Guzzon S.O., Claera-Olivera F., Brandelli A. Optimization of protease production by Microbacterium sp in feather meal using response surface methodology. Process Biochem. 2006;41:67–73. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsujibo H., Miyamoto K., Hasegawa T., Inamori Y. Purification and characterization of two alkaline serine proteases produced by an alkalophilic actinomycete. J. App. Bacteriol. 1990;69:520–529. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1990.tb01544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yeoman K.H., Edwards C. Protease production by Streptomyces thermovulgaris grown on rapemeal-derived media. J. Appl. Microbiol. 1994;77:264–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1994.tb03073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]