Abstract

Phylogenetic composition of bacterial community in soil of a karst forest was analyzed by culture-independent molecular approach. The bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified directly from soil DNA and cloned to generate a library. After screening the clone library by RFLP, 16S rRNA genes of representative clones were sequenced and the bacterial community was analyzed phylogenetically. The 16S rRNA gene inserts of 190 clones randomly selected were analyzed by RFLP and generated 126 different RFLP types. After sequencing, 126 non-chimeric sequences were obtained, generating 113 phylotypes. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that the bacteria distributed in soil of the karst forest included the members assigning into Proteobacteria, Acidobacteria, Planctomycetes, Chloroflexi (Green nonsulfur bacteria), Bacteroidetes, Verrucomicrobia, Nitrospirae, Actinobacteria (High G+C Gram-positive bacteria), Firmicutes (Low G+C Gram-positive bacteria) and candidate divisions (including the SPAM and GN08).

Keywords: karst forest, bacteria, 16S rRNA gene, Purification, Characterization

INTRODUCTION

Guizhou, a province in southwest of China, is the center of East-Asia developing karst area with a karst area over 5.5×105 km2 and is the largest and the most complex developing karst area in the world (44). Karst easily causes more rocks and less soil, serious soil erosion, difficult vegetation restoration, frequent drought, flooding disaster and poor moisture storage in the soil. As a result, the development of the regional forests is influenced and local farmers suffer from slow economic development (43).

Most forests distributed on karst landform are developed from soluble carbonate rocks and usually characterize by high surface rock exposing ratio, separate soil body, shallow topsoil layer and rich calcium (45). Guizhou had a forest area about 1.6×104 km2, with a mean forest coverage ratio of only 11.28% (41). In some counties, the forest coverage ratio is less than 5%, such as Shuicheng (2.57%), Ziyun (2.46%), Dafang (2.40%), and Zhijin (1.14%) (41). Due to rock desertification, the forest and soil area in this karst province decrease drastically (42). Thus, how to protect the forest is vital for improving the local climate and facilitating the economical development of this region.

For several decades, biologists have carried out their investigations on the biodiversity of plant and animal in Guizhou karst region (45), but few attentions were focused on soil microorganism. Recently, bacterial diversities in soils of various forest ecosystems have been studied based on ARDRA (33), DGGE (31), PLFA (9) analyses and so on. Soil bacterial composition of various vegetations had been reported, such as oak, beech (17), pine (24), spruce (4; 12), broad-leaved (10) and pristine forests (6; 22). However, few studies were focused on the phylogenetic diversity of soil bacteria of karst forest.

Soil bacteria are an essential component of the biotic community in natural forests and they are largely responsible for ecosystem function and diversity of life, but the vast majority of soil bacteria still remain unknown (34). Enrichment-based and cultural investigations on typical heterotrophic microbes have shown that microbes grow in proportion to less than 1% of total bacteria in an environment (2). The combination of amplification of bacterial 16S rRNA genes by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and phylogenetic sequence analysis by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) has become a powerful tool to investigate natural bacterial communities. The aim of the present study was to characterize the bacterial diversity in soil of karst forest and present the first knowledge to understand bacterial composition in such environment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Site description and sample collection

A forest predominantly formed by the plant Quercus glauca (25° 47′ N, 107° 48′ E), located in Dushan county, south of Guizhou province, was chosen for study. The mean annual temperature, precipitation and humidity in this region were 18.3ºC, 1320 mm and 80%, respectively. On April 15, 2006, 30 soil samples with a distance of 10 miters from each other were collected from 0~10 cm depth and mixed thoroughly as one for bacterial community analysis. The soil is black and calcareous, with pH 6.5.

Soil DNA extraction, PCR amplification and cloning

Soil DNA was extracted with a soil DNA isolation kit (Catalog #12800-50, MO BIO Laboratories, Inc., USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Bacterial 16S rRNA genes were amplified by PCR using the combination of bacterial primer 27f (5′ AGA GTT TGA TCC TGG CTC AG 3′) and universal primer 1492r (5′ GGT TAC CTT GTT ACG ACT T 3′) (26). The PCR reaction was performed in a thermal cycler with the following program: preheating at 95 ºC for 2 minutes, 25 cycles at 98ºC for 1 min, 50ºC for 40 s, 72ºC for 2 min and a final extension of at 72ºC for 10 minutes. The amplified products were purified using an agarose gel DNA purification kit (No. DV805A, Takara Bio Inc., Otsu, Japan). Bacterial 16S rRNA gene amplicon (ca. 1500 bases) was then excised from a 1% agarose gel and eluted with the same kit. Finally, the purified product was ligated into the pMD 18 T-vector (Takara Bio Inc., Otsu, Japan) and the ligation product was transformed into Escherichia coli DH-5α competent cells with ampicillin and blue/white screening following manufacturer’s instructions.

RFLP analysis

Inserts of 16S rRNA genes from recombinant clones were reamplified with vector primers M13-M3 (5′ GTAAAACGACGGCCAGT 3′) and M13-RV (5′ CAGGAAACAGCTATGAC 3′). The purified amplifications were subjected to restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) by separate enzymatic digestions with HhaI (Takara Bio Inc., Otsu, Japan) and MspI (Takara Bio Inc., Otsu, Japan) endonucleases following the manufacturer’s instructions, and the digested DNA fragments were electrophoresed in 3% agarose gels. After staining with ethidium bromide, the gels were photographed using an image-capture system UVITEC DBT-08, and scanning image analysis was performed manually.

DNA sequencing and phylogenetic analysis

One to three representative clones from each unique RFLP type were selected for sequencing. The 16S rRNA gene inserts were sequenced using plasmid DNA as template and M13-20 (5′ CGACGTTGTAAAACGACGGCCAGT 3′) or M13-RV-P (5′ GGAAACAGCTATGACCATGA TTAC 3′) as sequencing primer. Sequencing was done on an automated ABI 3730 sequencer by Beijng Genomics Institute. The resulting sequences (next to the primer 1492r and at least 600 bp) were compared with those available in GenBank by use of the BLAST method to determine their approximate phylogenetic affiliation and 16S rRNA gene sequence similarities (1; 14). Chimeric sequences were identified by use of the CHECK-CHIMERA program of the Ribosomal Database Project (30), and by independently comparing the alignments at the beginning and the end of each sequence and the alignments of the entire sequence. Sequences differing only slightly (≤3%) were considered as a phylotype, and each phylotype was represented by a type sequence (19). Nucleotide sequences were initially aligned using Clustal X (40) and then manually adjusted. Distance matrices and phylogenetic trees were calculated according to the Kimura two-parameter model (23) and neighbor-joining (36) algorithms using the MEGA (version 3.1) software packages (25). One thousand bootstraps were performed to assign confidence levels to the nodes in the trees.

The 16S rRNA gene sequences have been deposited in the GenBank nucleotide sequence database under Accession Nos. EF141940–EF142065.

Diversity index

Bacterial diversity was indicated using the Shannon–Weaver index (H′) (38).

N is the number of operational taxonomic units (OTU) or RFLPs, and Pi is the percentage of clones of the ith OTU or the relative abundance of the ith RFLP.

RESULTS

Diversity of soil bacteria from the karst forest

A total of 190 recombinant clones were randomly selected, and their 16S rRNA gene inserts were subjected to restriction endonuclease analysis (RFLP), resulting 126 different RFLP types. After sequencing and CHECK-CHIMERA analysis, 126 non-chimeric sequences were obtained, generating 113 phylotypes. Eighty sequences (63.5% of total sequences) each represented a single clone and 35 sequences (27.8%) each represented two clones. Comparative analysis of the retrieved sequences showed that all clones belonged to the Bacteria domain. It was determined that most relatives of sequences (101 sequences representing 154 clones, 81.1% of total sequences) were related to sequences from environmental clones and 31 sequences (24.6%) had relatively low levels of similarity (<94%) with their closest counterparts in the GenBank databases (Table 1, Figure 1-3). No sequence was most related to bacterial sequence detected in other forests or karst areas in the public databases except the clone FAC10 (DQ451449) from a Taiwan forest, relative of KF092 and belonging to the Acidobacteria (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Distribution of clones and RFLP types or sequences from soil of karst forest

| Putative phylogenetic affiliationa | No. of clones | % of clones | No. of sequencesb | % of sequences | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Proteobacteria | 69 | 36.4 | 47 | 37.2 | 89-99 |

| 1.1 Alphaproteobacteria | 19 | 10.0 | 11 | 8.7 | 91-99 |

| 1.2 Betaproteobacteria | 17 | 9.0 | 12 | 9.5 | 92-99 |

| 1.3 Gammaproteobacteria | 18 | 9.5 | 13 | 10.3 | 94-99 |

| 1.4 Deltaproteobacteria | 15 | 7.9 | 11 | 8.7 | 89-99 |

| 2. Acidobacteria | 45 | 23.7 | 26 | 20.6 | 90-98 |

| 3. Planctomycetes | 22 | 11.6 | 13 | 10.3 | 87-96 |

| 4. Actinobacteria | 20 | 10.5 | 14 | 11.1 | 90-99 |

| 5. Chloroflexi | 5 | 2.6 | 4 | 3.2 | 85-93 |

| 6. Bacteroidetes | 7 | 3.7 | 6 | 4.8 | 94-98 |

| 7. Verrucomicrobia | 6 | 3.2 | 6 | 4.8 | 91-97 |

| 8. Nitrospirae | 7 | 3.5 | 5 | 4.0 | 95-98 |

| 9. Firmicutes | 2 | 1.1 | 2 | 1.6 | 95-97 |

| 10.Candidate division | 7 | 3.7 | 3 | 2.4 | 89-99 |

Closest relatives as determined by the BLAST method.

Each sequence representing a single RFLP type. S: The sequence similarity to its closest relatives.

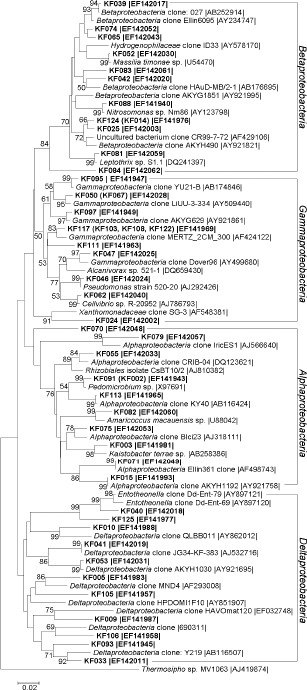

Figure 1.

16S rRNA gene-based dendrogram showing phylogenetic relationships of bacterial phylotypes from karst forest soil (shown in bold) to members of the Proteobacteria from public database. Bootstrap values (n=1000 replicates) of ≥50% are reported as percentages. The scale bar represents the number of changes per nucleotide position. Thermosipho sp. MV1063 (AJ419874) was used as outgroup. Sequences of RFLP types differing only slightly (≤3%) are shown in parentheses. Accession numbers are given at the end of each sequence.

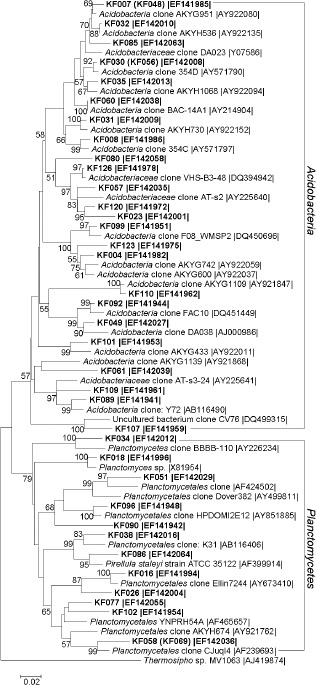

Figure 2.

16S rRNA gene-based dendrogram showing phylogenetic relationships of bacterial phylotypes from karst forest soil (shown in bold) to members of the Acidobacteria and Planctomycetes from public database. Bootstrap values (n=1000 replicates) of ≥50% are reported as percentages. The scale bar represents the number of changes per nucleotide position. Thermosipho sp. MV1063 (AJ419874) was used as outgroup. Sequences of RFLP types differing only slightly (≤3%) are shown in parentheses. Accession numbers are given at the end of each sequence.

Phylogenetic analysis on the soil bacteria from the karst forest

Phylogenetic analyses placed the 113 phylotypes in the following 10 groups of the domain Bacteria: the Proteobacteria, Acidobacteria, Planctomycetes, Chloroflexi (Green nonsulfur bacteria), Bacteroidetes, Verrucomicrobia, Nitrospirae, Actinobacteria (High G+C Gram-positive bacteria), Firmicutes (Low G+C Gram-positive bacteria) and candidate divisions (including the SPAM and GN08) (Figure 1.-3). Among them, the Proteobacteria was the largest group including 69 clones, followed by Acidobacteria (45 clones), Planctomycetes (22 clones) and Actinobacteria (20 clones) (Table 1).

Proteobacteria

Sixty-nine clones, represented by 47 sequences and accounting for 36.4% of the clone library, were phylogenetically associated with the following taxa of Proteobacteria with similarities between 89%–99%: the Alphaproteobacteria (number of sequences, ns=11, number of clones, nc=19), Betaproteobacteria (ns=12, nc=17), Gammaproteobacteria (ns=13, nc=18) and Deltaproteobacteria (ns=11, nc=15) (Table 1, Figure 1).

A total of sixteen clones, represented by 10 sequences, were related to cultured members and belonged to putatively Sphingomonadales (sequence KF003), Rhizobiales (KF091 and KF002), Rhodospirillales (KF082), Nitrosomonadales (KF088), Burkholderiales (KF052 and KF081), Xanthomonadales (KF024) and Pseudomonadales (KF046 and KF062). Sequences KF040, KF125 and their closest relatives (Entotheonella clones) were grouped in a clade with a bootstrap confidence value of 99% (Figure 1). Entotheonella, a new Deltaproteobacteria genus, had been found thus far only in sponges of the family Theonellidae (37).

Acidobacteria

Forty-five clones, represented by 26 sequences and accounting for 23.7% of the clone library, were clustered with the uncultivated bacterial sequences of the Acidobacteria with similarities between 90%–98% (Table 1, Figure 2). Figure 2 showed a phylogenetic tree of Acidobacteria, which was grouped into at least 5 acidobacterial clusters. Acidobacteria form a newly devised division of Bacteria, probably as diverse as Proteobacteria or gram-positive bacteria. The definition of this phylum was based on the analysis of 16S rRNA gene sequences retrieved from cloned rRNA genes and phylogenetically related to several cultivated species such as the Fe (III)-reducing Geothrix fermentans (29; 35). The clone F08_WMSP2 (DQ450696), relative of KF099, was detected in Alpine tundra wet meadow soil. The clone DA038 (AJ000986), relative of KF049 respectively, was found from a grassland soil in the Netherlands.

Planctomycetes

Thirteen sequences, representing 22 clones (11.6% of the clone library), were grouped into the Planctomycetes. Seven sequences were related with relatively low similarities between 87%–93% to cultured or uncultured bacterial sequences listed in the GeneBank database (Table 1, Figure 2). Molecular microbial ecology has provided new evidence showing that Planctomycetes bacteria are ubiquitous and constitute a representative part of the natural bacterial population (20). The sequence HPDOMI2E12 (AY851885), which was clustered with KF096, was a member from stromatolites of Hamelin Pool in Shark Bay, Western Australia.

Actinobacteria

Fourteen sequences, representing 20 clones (10.5% of the clone library), were clustered with the Actinobacteria (Table 1, Figure 3). These bacterial clones were related with similarities between 90%–99% to cultured or uncultured bacterial sequences listed in the GeneBank database. Five sequences were related to classified members and belonged to putatively the Actinomycetales (KF043) and Rubrobacterales (KF012, KF017, KF066 and KF068).

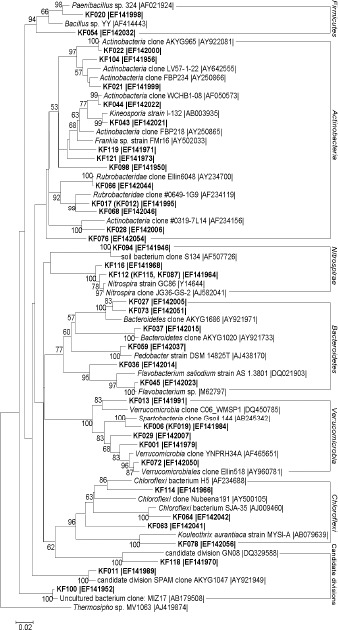

Figure 3.

16S rRNA gene-based dendrogram showing phylogenetic relationships of bacterial phylotypes from karst forest soil (shown in bold) to members of the Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Nitrospirae, Bacteroidetes, Verrucomicrobia, Chloroflexi and Candidate divisions from public database. Bootstrap values (n=1000 replicates) of ≥50% are reported as percentages. The scale bar represents the number of changes per nucleotide position. Thermosipho sp. MV1063 (AJ419874) was used as outgroup. Sequences of RFLP types differing only slightly (≤3%) are shown in parentheses. Accession numbers are given at the end of each sequence.

Chloroflexi (Green nonsulfur bacteria)

Four sequences representing 5 clones were related to Chloroflexi sequences listed in the GeneBank database (85%-93% similarity) (Table 1, Figure 3). The low similarities to these members indicated that the corresponding bacteria detected in the soil of karst forest belonged to putatively new taxonomic groups.

Bacteroidetes, Verrucomicrobia, Nitrospirae and Firmicutes

Six sequences were clustered with the Bacteroidetes (Table 1, Figure 3). The closest relatives of KF059 and KF036 (KF045) were strains belonging to the Flavobacteriaceae and Sphingobacteriales, respectively. Some species in the Flavobacteriaceae degrade soluble cellulose derivatives, and nine cellulolytic isolates were assigned to Flavobacterium johnsoniae (27). Six sequences were grouped with uncultured bacterial sequences of the Verrucomicrobia. Furthermore, five and two sequences were closely related to the Nitrospirae and Firmicutes, respectively. KF020 and KF054 were related to classified members and belonged to putatively the Bacillales.

DISCUSSION

To date, few molecular microbiological data on bacterial community in soil of karst forest were presented. We firstly presented the knowledge on bacterial community and revealed a considerable number of novel and unknown bacterial sequences and a high diversity of putative bacterial communities in this environment. Sequences with low similarities (<94%) to bacterial sequences listed in the GeneBank database were mainly distributed in Deltaproteobacteria, Acidobacteria, Planctomycetes, Actinobacteria and Chloroflexi (Table 1). Clones of the Proteobacteria, Acidobacteria, Planctomycetes and Actinobacteria accounted for more than 80% of the clone library, while that of other 6 groups each accounted for less than 4%. That confirmed Proteobacteria, Acidobacteria, Planctomycetes and Actinobacteria were absolutely the dominating communities in soil of karst forest. Besides, Proteobacteria and Acidobacteria were two largest groups (more than 60% of the clone library) (Table 1).

Diversity of bacterial communities in soil of karst forest was quite different with that in other forests reported until now (Table 2). The Shannon–Weaver index (H′) of karst forest (2.32) was higher than others forests, including the British Columbia forest. This reflected bacterial diversity in the ecosystem is higher than that in other forests. Karst forest was a relatively fragile ecosystem type (45). The high bacterial diversity in soil of karst forest could possibly contribute to its tolerance for natural disturbance and self-recovery and regeneration processes.

Table 2.

Distribution of bacteria in forest soils investigated by molecular method

| Putative phylogenetic affiliation | % of clones from forests with different vegetations and in different locations | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spruce in Rothwald, Austria (17) | Spruce in Britsh Columbia, Canada (4) | Spruce in British Columbia, Canada (12) | Pine in Ungaran, Indonesia (24) | Pristine in Western Amazon, Brazil (22) | Pristine in Eastern Amazon, Brazil (6) | Broad-leave in Ailaoshan, China (10) | Broad-leave in Xishuangbanna, China (10) | Quercus in Guizhou, China (this study) | |

| 1. Proteobacteria | 45.0 | 46.5 | 55.2 | 54.1 | 30.7 | 12.2 | 28.0 | 15.0 | 36.4 |

| 1.1 Alphaproteobacteria | 27.0 | 21.0 | 24.4 | 40.5 | 18.4 | 4.1 | 3.0 | 6.0 | 10.0 |

| 1.2 Betaproteobacteria | 6.0 | 11.0 | 19.0 | 6.8 | 4.1 | 2.0 | 9.0 | 8.0 | 9.0 |

| 1.3 Gammaproteobacteria | 6.0 | 14.0 | 9.0 | 4.1 | 8.2 | 2.0 | 12.0 | 1.0 | 9.5 |

| 1.4 Deltaproteobacteria | 6.0 | 0.5 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 7.9 | ||

| 2. Acidobacteria | 35.0 | 9.0 | 18.8 | 1.4 | 49.0 | 48.0 | 80.0 | 23.7 | |

| 3. Planctomycetes | 10.0 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 4.1 | 2.0 | 13.0 | 1.0 | 11.6 | |

| 4. Actinobacteria | 15.0 | 3.1 | 36.5 | 6.1 | 10.5 | ||||

| 5. Chloroflexi | 0.5 | 2.6 | |||||||

| 6. Bacteroidetes | 3.0 | 3.4 | 6.1 | 3.7 | |||||

| 7. Verrucomicrobia | 10.0 | 12.0 | 3.1 | 6.1 | 12.2 | 7.0 | 1.0 | 3.2 | |

| 8. Nitrospirae | 3.5 | ||||||||

| 9. Firmicutes | 0.5 | 4.1 | 22.4 | 1.1 | |||||

| 10. Fibrobacter | 18.6 | ||||||||

| 11. Chlamydia | 2.0 | 2.0 | |||||||

| 12. Othersb | 12.5 | 16.4 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 24.5 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 3.7 | |

| H’a | 1.69 | 2.09 | 1.92 | 1.49 | 1.63 | 1.99 | 1.64 | 0.79 | 2.32 |

H’ (Shannon–Weaver index) was calculated for estimation of bacterial diversity, using phyla as OUT.

Including candidate divisions, unclassified.

Composition of bacterial communities in soil of karst forest was also unique (Table 2), which was putatively related to unknown soil environmental variables. Although the forests with broad-leaved in Ailaoshan, Xishuangbanna (10) and this study site are located in the Southwest of China, their compositions of bacterial communities are totally quite different (except the group of Betaproteobacteria, Table 2). Similar results were obtained from the spruce forests in British Columbia, Canada (4, 12) (especially the difference of Acidobacteria, Actinobacteria and Verrucomicrobia, Table 2) and from the pristine forests in Brazil (6, 22) (especially the difference of Proteobacteria, Acidobacteria, Firmicutes and Fibrobacter, Table 2). That seemed compositions of bacterial communities from soil of forest were largely independent of vegetation types and geographic distance. But Fierer and Jackson (15) discussed that bacterial diversity and community composition could largely be explained by soil pH, but unrelated to plant diversity and geographic distance, respectively.

The closest relatives of KF088 and KF112, with a high similarity value of more than 97%, were strains belonging to Nitrosomonas and Nitrospira respectively (Figure 1, 3). Nitrosomonas is a genus of ammonia-oxidizing proteobacteria (39). Nitrospira strains are the dominant nitrite oxidizers in most environmental samples tested so far (8). The Rhizobiales is famous for nitrogen-fixing bacteria that form nodules on host plants (7). Some strains of the Burkholderiales are capable of nitrogen fixation, such as Ralstonia taiwanensis (11). And the closest relative of KF062 was Cellvibrio bacteria that are capable of cellulose-degrading, such as Cellvibrio fulvus (5) (Figure 1). Based on culture-dependent method, Long et al. (28) reported ammonifiers (7.6×106 bacteria per gram soil), nitrobacteria (1.14×103), nitrogen fixing bacteria (1.28×103) and cellulose decomposers (5.68×104) in soil of Maolan karst forest.

The closest relatives of KF091 and KF081 were Pedomicrobium and Leptothrix strains respectively (Figure 1). Pedomicrobium plays an important role in iron- and manganese-oxidization (16). Leptothrix is known to be capable of oxidizing both iron (II) and manganese (II) to ferric hydroxide and manganese oxide (13). Relatives of KF113, KF033, KF089 and KF038 are clones detected in coastal marine sediment beneath areas of intensive shellfish aquaculture where sulfur cycle was accelerated (3). It has been reported that sulfur-oxidizing bacteria play a role in the dissolution of limestone (32).

The Acidobacteria and the Planctomycetes were poorly studied phylogenetic divisions that have been detected in many clonal analyses and are thought to be of great ecological significance to many ecosystems (18; 29). But as limited cultivated species, their ecological functions and possible impacts on soils remain unclear at present. Two novel genera of the Planctomycetes, Candidatus Kuenenia stuttgartiensis and Candidatus Brocadia annamoxidans are capable of catalyzing the anaerobic oxidation of ammonium (21).

Our present study has given a useful insight into bacterial populations in soil of karst forest and can be used as a starting point for in-depth studies. Although studies based on culture-independent methods make more difficult valid statements about the ecological role that clones might play in the environment, such studies will help understand the diversity and structure of bacterial communities in soil of karst forest and contributions of bacteria to the ecosystem.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported jointly by “National Basic Research Program of China” (2007CB116310, 2007CB411600), NSFC (30760002) and projects of Department of Science and Technology of Yunnan Province (2006XY41, 2006C0005M).

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S.F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E.W., Lipman D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amann R.I., Ludwig W., Schleifer K.H. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol. Rev. 1995;59:143–169. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.143-169.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asami H., Aida M., Watanabe K. Accelerated sulfur cycle in coastal marine sediment beneath areas of intensive shellfish aquaculture. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71:2925–2933. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.6.2925-2933.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Axelrood P.E., Chow M.L., Radomski C.C., McDermott J.M., Davies J. Molecular characterization of bacterial diversity from British Columbia forest soils subjected to disturbance. Can. J. Microbiol. 2002;48:655–674. doi: 10.1139/w02-059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berg B., Hofsten B.V., Pettersson G. Electronmicroscopic obsetvations on the degradation of cellulose fibres by Cellvibrio fulvus and Sporoctphaga myxococcoides. J. Appl. Bact. 1972;35:215–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1972.tb03692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borneman J., Triplett E.W. Molecular microbial diversity in soils from eastern Amazonia: evidence for unusual microorganisms and microbial population shifts associated with deforestation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997;63:2647–2653. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.7.2647-2653.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bottomley P.J. Ecology of Bradyrhizobium and Gluconoacetobacter diazotrophicusobium. In Biological Nitrogen Fixation. In: Stacey G., Burris R.H., Evans H.J., editors. London: Chapman and Hall New York; 1992. pp. 293–348. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burrell P.C., Keller J., Blackall L.L. Microbiology of a nitrite-oxidizing bioreactor. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998;64:1878–1883. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.5.1878-1883.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Busse M.D., Beattie S.E., Powers R.F., Sanchez F.G., Tiarks A.E. Microbial community responses in forest mineral soil to compaction, organic matter removal, and vegetation control. Can. J. For. Res. 2006;36:577–588. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan O.C., Yang X., Fu Y., Feng Z., Sha L., Casper P., Zou X. 16S rRNA gene analyses of bacterial community structures in the soils of evergreen broad-leaved forests in south-west China. FEMS Microb. Ecol. 2006;58:247–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2006.00156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen W.M., Laevens S., Lee T.M., Coenye T., De Vos P., Mergeay M., Vandamme P. Ralstonia taiwanensis sp. nov., isolated from root nodules of Mimosa species and sputum of a cystic fibrosis patient. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2001;51:1729–1735. doi: 10.1099/00207713-51-5-1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chow M.L., Radomski C.C., McDermott J.M., Davies J., Axelrood P.E. Molecular characterization of bacterial diversity in Lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta) rhizosphere soils from British Columbia forest soils differing in disturbance and geographic source. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2002;42:347–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2002.tb01024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DE Vrind-DE Jong E.W., Corstjens P.L.A.M., Kempers E.S., Westbroek P., DE Vrind J.P.M. Oxidation of manganese and iron by Leptothrix discophora: use of N,N,N’,N’ tetramethyl p phenylenediamine as an indicator of metal oxidation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1990;56:3458–3462. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.11.3458-3462.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engel A.S., Porter M.L., Stern L.A., Quinlan S., Bennett P.C. Bacterial diversity and ecosystem function of filamentous microbial mats from aphotic (cave) sulfidic springs dominated by chemolithoautotrophic “Epsilonproteobacteria”. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2004;51:31–53. doi: 10.1016/j.femsec.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fierer N., Jackson R.B. The diversity and biogeography of soil bacterial communities. PNAS. 2006;103:626–631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507535103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghiorse W.C., Hirsch P. Iron and manganese deposition by budding bacteria. In Environmental Biogeochemistry and Geotnicrohiology. In: Krumbein W.E., editor. Vol. 3. 10. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Ann Arbor Science Publishers; 1978. pp. 897–9. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hackl E., Zechmeister Boltenstern S., Bodrossy L., Sessitsch A. Comparison of diversities and compositions of bacterial populations inhabiting natural forest soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;70:5057–5065. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.9.5057-5065.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holmes A.J., Tujula N.A., Holley M., Contos A., James J.M., Rogers P., Gillings M.R. Phylogenetic structure of unusual aquatic microbial formations in Nullarbor Caves, Australia. Environ. Microbiol. 2001;3:256–264. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2001.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang L.N., Zhou H., Zhu S., Qu L.H. Phylogenetic diversity of bacteria in the leachate of a full-scale recirculating landfill. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2004;50:175–183. doi: 10.1016/j.femsec.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hugenholtz P., Goebel M.B., Pace N.R. Impact of culture-independent studies on the emerging phylogenetic view of bacterial diversity. J. Bacteriol. 1998;180:4765–4774. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.18.4765-4774.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jetten M., Wagner M., Fuerst J., van Loosdrecht M., Kuenen G., Strous M. Microbiology and application of the anaerobic ammonium oxidation "anamox" process. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2001;12:283–288. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(00)00211-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim J.S., Sparovek G., Regina M.L., MELO W.J., Crowley D. Bacterial diversity of terra preta and pristine forest soil from the Western Amazon. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2007;39:684–690. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kimura M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rate of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 1980;16:111–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01731581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krave A.S., Lin B., Braster M., Laverman A.M., van Straalen N.M., Roling W.F.M., van Verseveld H.W. Stratification and seasonal stability of diverse bacterial communities in a Pinus merkusii (pine) forest soil in central Java, Indonesia. Environ. Microbiol. 2002;4:361–373. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar S., Tamura K., Nei M. MEGA3: Integrated software for molecular evolutionary genetics analysis and sequence alignment. Brief. Bioinform. 2004;5:150–163. doi: 10.1093/bib/5.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lane D.J. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing. In Nucleic Acid Techniques in Bacterial Systematics. In: Stackebrandt E., Goodfellow M. Wiley, editors. New York; 1991. pp. 115–175. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lednicka D., Mergaert J., Cnockaert M.C., Swings J. Isolation and identification of cellulolytic bacteria involved in the degradation of natural cellulosic fibres. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2002;23:292–299. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(00)80017-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Long J., Li J., Jiang X.R., Huang C.Y. Soil microbial activities in Maolan karst forest, Giuzhou province. Acta Pedologica Sinica. 2004;41:597–602. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ludwig W., Bauer S.H., Bauer M., Held I., Kirchhof I., Schulze R., Schleifer K.H. Detection and in situ identification of representatives of a widely distributed new bacterial phylum. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1997;153:181–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maidak B.L., Olsen G.J., Larsen N., Overbeek R., McCaughey M.J., Woese C.R. The RDP ribosomal database project. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:109–110. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.1.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neufeld J.D., Mohn W.W. Unexpectedly high bacterial diversity in arctic tundra relative to boreal forest soils, revealed by serial analysis of ribosomal sequence tags. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71:5710–5718. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.10.5710-5718.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Northup D.E., Lavoie K.H. Geomicrobiology of caves: a review. Geomicrobiol. J. 2001;18:199–222. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nüsslein K., Tiedje J.M. Soil Bacterial community shift correlated with change from forest to pasture vegetation in a tropical soil. Appl. Envir. Microbiol. 1999;65:3622–3626. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.8.3622-3626.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pace N.R. A molecular view of microbial diversity and the biosphere. Science. 1997;276:734–740. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5313.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quaiser A., Ochsenreiter T., Lanz C., Schuster S.C., Treusch A.H., Eck J., Schleper C. Acidobacteria form a coherent but highly diverse group within the bacterial domain: evidence from environmental genomics. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;50:563–575. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saitou N., Nei M., Lerman L.S. The neighbor joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schirmer A., Gadkari R., Reeves C.D., Ibrahim F., DeLong E.F., Hutchinson C.R. Metagenomic analysis reveals diverse polyketide synthase gene clusters in microorganisms associated with the marine sponge Discodermia dissoluta. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71:4840–4849. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.8.4840-4849.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shannon C.E, Weaver W. Urbana: University of Illinois Press; 1963. The mathematical theory of communication. pp. 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suzuki I., Dular U., Kwok S.C. Ammonia or ammonium ion as substrate for oxidation by Nitrosomonas cells and extracts. J. Bacteriol. 1974;120:556–558. doi: 10.1128/jb.120.1.556-558.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thompson J.D., Gibson T.J., Plewniak F., Jeanmougin F., Higgens D.G. The Clustal X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;24:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tu Y.L. Karst forests in Guizhou. Carsologica Sinica. 1989;8:282–290. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang H. Discussion on variation of karst environmental quality. In: Xie Y., Yang M., editors. Human Activity and Karst Environment. Beijing: Beijing Science and Technology Press; 1994. pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu L.F. The assessment on the natural restoration of degraded Karst forests. Forest. Sci. 2000;36:12–19. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang Y.J., Yang M.D., He C.H. Karst geomorphology and environmental implication in Guizhou. Cave Science. 1992;19:13–20. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhu S.Q. Guiyang: Guizou Sci-Tech Press; 1997. Ecological research on Karst Forests (α). pp. 57–63. [Google Scholar]