Abstract

We report a case of cavitary pneumonia caused by N. otitidiscaviarum in a man with diabetes mellitus and thrombocytopenia treated with systemic corticosteroid. Taxonomic identification involved phenotypic testing and molecular identification that was carried out by DNA sequencing of the 16SrRNA gene.

Keywords: Nocardia otitidiscaviarum, pneumonia, 16SrRNA gene

Nocardial infection usually occurs as an opportunistic pulmonary or disseminated infection (14) and more rarely as a subcutaneous disease known as actinomycotic mycetoma caused by direct skin inoculation (11). The diagnosis is often delayed because the disease is not included in the differential diagnosis. Infections due to N. otitidiscaviarum appear to be rare compared with those caused by other species of Nocardia, although it can cause pulmonary infections in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients (6, 17). We present the case of a patient being treated with systemic corticosteroids who developed a serious pulmonary infection caused by N. otitidiscaviarum.

We report a case of a 57-year-old man who presented fever, progressive dyspnoea and asthenia compatibles with pulmonary infection. Demographic data included diabetes mellitus and thrombocytopenia and he was receiving corticosteroid therapy. Radiographic finding was a lung nodule with 7 cm cavitation in lower right lobe and a computed tomography scan of the chest revealed consolidation throughout the lower right lobe and one nodule compatible with cavitary pneumonia.

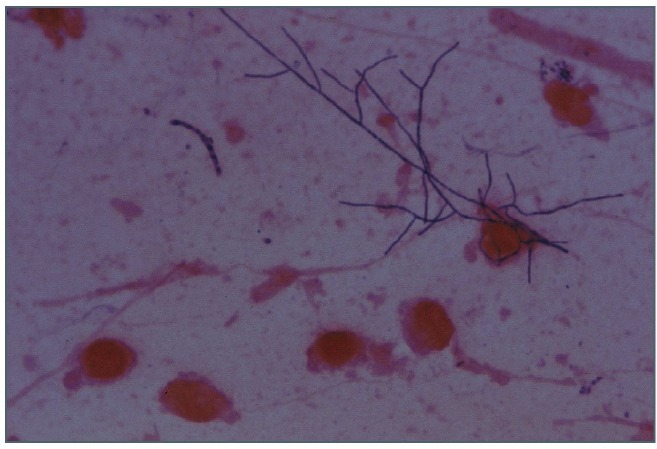

Sputum specimen was smeared and stained by Gram’s technique. The initial microscopic examination showed polymorphonuclear cells and gram-positive branched diphtheroid to filamentous bacterium staining consistent with Nocardia (Figure 1). The sample was cultured on blood agar medium, chocolate agar, Buffered Charcoal Yeast Extract Agar (BCYE) plates and incubated at 35ºC. After three days of incubation, small, white and irregular colonies could be observed and subcultured on plates containing casein, tyrosine, xanthine, hypoxanthine and Middlebrook 7H10. Gram and Ziehl-Neelsen modified stain of the colonies showed gram positive bacilli and rod-shaped elements forming mycelia.

Figure 1.

Gram 1000x. Nocardia otitidiscaviarum in sputum.

The organism was initially characterized on the basis of routine phenotypic test results in our laboratory (typical colony appearance, positive Gram stain, degradation of casein, tyrosine, xanthine, hypoxanthine and Middlebrook) and also a molecular identification was carried out by DNA sequencing of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene as described Rodríguez-Nava et al. (15). A 606 nt fragment was obtained and compared to the Genbank and BIBI databases. The results showed 100 % similarity sequence between our isolate and the type strain of N. otitidiscaviarum species. This approach allowed us to confirm the identification of the sputum isolate and to diagnose a pulmonary nocardiosis due to N. otitidiscaviarum.

The susceptibility of the isolate to different antimicrobials was determined by broth microdilution method, as recommended by the CLSI for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of nocardiae (12). Appropriate dilutions for MIC determinations were obtained from EMIZA 9EF Sensititre® plates and containing an equal volume of broth and serial dilutions of the drugs to be tested. The control recommended reference strain each day test was performed (Escherichia coli ATCC( 35218 and S. aureus ATCC 29213(). The plate was incubated at 37ºC for 72 hours. The MICs were interpreted in accordance with the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards guidelines (12). The organism was resistant to imipenem (>8), amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (>16/8), cefotaxime (>32), tobramycin (>8), ciprofloxacin (>2) and susceptible to amikacin (≤4), gentamycin (≤1) and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (1/19).

Nocardia are aerobic Gram-positive bacteria of the order Actinomycetales. They have a worldwide distribution and are commonly found in dust, sand, soil and stagnant water. Human infections can be divided clinically into pulmonary nocardiosis, systemic nocardiosis, central nervous system nocardiosis, extrapulmonary and localized nocardiosis, cutaneous and subcutaneous nocardiosis and nocardial mycetoma. (3). The incidence of nocardial infections is as yet unknown, and their prevalence is almost certainly underestimated (4).

N. otitidiscaviarum was first described by Snijders in 1924 (16) from a Sumatran cavy or guinea pig with ear disease and was considered to be a soil saprophyte until the first systemic infections in man were reported in 1974 (8). In humans, N. otitidiscaviarum is rarely isolated in nontropical countries and is known to be a cause of primary cutaneous, lymphocutaneous, and pulmonary infections in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients (7). Infections due to N. otitidiscaviarum appear to be rare compared to those caused by other species of Nocardia (9, 13) and the low incidence may be attributed to reduced pathogenicity or its lower prevalence in soil compared with other Nocardia species (10).

Pulmonary nocardiosis is an uncommon but severe pulmonary infection (2) and can be acute, subacute or chronic with a marked tendency towards remissions and exacerbations. The majority of the pulmonary nocardiosis occurs in patients with suppression of cell-mediated immune response and the most frequent predisposing factors are chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, underlying malignancies, HIV-infection or corticosteroid therapy like in the present case. Glucocorticoid is well recognized and widely used for immune suppression and it is one of the great risk factors for invasive nocardiosis (1, 11). In our patient, corticosteroid administration, diabetes mellitus and thrombocytopenia were considered to be the major contributors to his impaired immunity in line with previous reports (11).

Biochemically, this strain showed its ability to hydrolyze hypoxanthine and xantine and did not produce opacity of Middlebrook 7H10 agar.

Isolates of N. otitidiscaviarum complex are usually resistant to beta-lactams, including most broad-spectrum cephalosporins, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, and imipenem, but are usually susceptible to amikacin, fluoroquinolones, and sulfonamides (5, 6). The isolate showed in vitro antibiotic susceptibilities similar to those reported previously (6). The patient was treated with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole which was selected by susceptibility tests and the clinical outcome was favorable after treatment.

In most of the patients with lung nocardiosis, early diagnosis and proper treatment allow successful clinical evolution. A high level of clinical suspicion is required in patients with risk factors, because infections due to N. otitidiscaviarum seem to be rare but it is also possible that they are more common and not properly diagnosed. Microbiologist must be informed in such cases to include stains and specific cultures to investigate the presence of Nocardia. This may lead to an early diagnosis and a prompt initiation of appropriate treatment, based in susceptibility test performed in the laboratory.

This case shows that nocardiosis may be the cause of a serious lung infection presenting cavitary pneumonia caused by an antimicrobial resistant N. otitidiscaviarum.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ando T., Usa T., Ide A., Abe Y., Sera N., Tominaga T., Ejima E., Ashizawa K., Nakata K., Eguchi K. Pulmonary nocardiosis associated with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Intern. Med. 2001;40:246–249. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.40.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beaman B.L., Burnside J., Edwards B., Causey W. Nocardial infections in the United States, 1972-1974. J. Infect. Dis. 1976;134:286–289. doi: 10.1093/infdis/134.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beaman B.L., Saubolle M.A., Wallace R.J. Nocardia, Rhodococcus, Streptomyces, Oerskovia, and other aerobic actinomycetes of medical importance. In: Murray P.R., Baron E.J., Pfaller M.A., Tenover F.C., Yolken R.H., editors. 6th. American Society for Microbiology,Washington, D.C: Manual of clinical microbiology; 1995. pp. 379–399. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boiron P., Provost F., Chevrier G., Dupont B. Review of nocardial infections in France 1987 to 1990. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1992;11:709–714. doi: 10.1007/BF01989975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boiron P., Provost F. Characterization of Nocardia, Rhodococcus and Gordona species by in vitro susceptibility testing. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. 1990;274:203–213. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(11)80103-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown-Elliott B.A., Brown J.M., Conville P.S., Wallace R. J., Jr. Clinical and laboratory features of the Nocardia spp. based on current molecular taxonomy. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2006;19:259–282. doi: 10.1128/CMR.19.2.259-282.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castelli L., Zlotnik H., Ponti R., Vidotto V. First reported Nocardia otitidiscaviarum infection in an AIDS patient in Italy. Mycopathologia. 1994;126:131–136. doi: 10.1007/BF01103766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Causey W.A., Arnell P., Brinker J. Systemic Nocardia caviae infection. Chest. 1974;65:360–362. doi: 10.1378/chest.65.3.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark N.M., Braun D.K., Pasternak A., Chenoweth C.E. Primary cutaneous Nocardia otitidiscaviarum infection: case report and review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1995;20:1266–1270. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.5.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Durán E., López L., Martínez A., Comuñas F., Boiron P., Rubio M.C. Primary brain abscess with Nocardia otitidiscaviarum in an intravenous drug abuser. J. Méd. Microbiol. 2001;50:101–103. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-50-1-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hui C.H., Au V.W., Rowland K., Slavotinek J.P., Gordon D.L. Pulmonary nocardiosis re-visied: experience of 35 patients at diagnosis. Respir Med. 2003;97:709–7. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2003.1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.NCCLS. Wayne, PA: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 2003. Susceptibility testing of mycobacteria, nocardia, and other aerobic actinomycetes, vol. 23: Approved standard M24-A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pelaez A.I., Garcia-Suarez M.M., Manteca A., Melon O., Aranaz C., Cimadevilla R., Mendez F.J., Vazquez F. A fatal case of Nocardia otitidiscaviarum pulmonary infection and brain abscess: taxonomic characterization by molecular techniques. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2009;8:11. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-8-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Provost F., Laurent F., Camacho Uzcategui L.R., Boiron P. Molecular study of persistence of Nocardia asteroides and Nocardia otitidiscaviarum strains in patients with long-term nocardiosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1997;35:1157–1160. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.5.1157-1160.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodríguez-Nava V., Couble A., Devulder G., Flandrois J.P., Boiron P., Laurent F. Use of PCR-restriction enzyme pattern analysis and sequencing database for hsp65 gene-based identification of Nocardia species. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:536–546. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.2.536-546.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Snijders E.P. Verslag van het wetenschappenllijk gdeelte der vergaderingen van der afdelling Sumatra’s oostkurst. Geneesk. Tijdschr. Ned. IndiË. 1924;64:75–77. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoshida K., Bandoh S., Fujita J., Tokuda M., Negayama K., Ishida T. Pyothorax caused by Nocardia otitidiscaviarum in a patient with rheumatoid vasculitis. Intern. Med. 2004;43:615–9. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.43.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]