Abstract

The inhibitory effects of fifteen chitosans with different degrees of polymerization (DP) and different degrees of acetylation (FA) on the growth rates (GR) of four phytopathogenic fungi (Alternaria alternata, Botrytis cinerea, Penicillium expansum, and Rhizopus stolonifer) were examined using a 96-well microtiter plate and a microplate reader. The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of the chitosans ranged from 100 μg ×mL-1 to 1,000 μg ×mL-1 depending on the fungus tested and the DP and FA of the chitosan. The antifungal activity of the chitosans increased with decreasing FA. Chitosans with low FA and high DP showed the highest inhibitory activity against all four fungi. P. expansum and B. cinerea were relatively less susceptible while A. alternata and R. stolonifer were relatively more sensitive to the chitosan polymers. Scanning electron microscopy of fungi grown on culture media amended with chitosan revealed morphological changes.

Keywords: chitosan, antifungal activity, fungal morphology, phytopathogenic fungi

INTRODUCTION

Chitin and chitosan are aminoglucopyranans composed of N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) and glucosamine (GlcN) residues, and are renewable resources currently being studied by academic and industrial groups (29) owing to their attractive properties and biological activities. Chitosans have been indicated for the preservation of foods (5, 34) juices (32) and other material from microbial deterioration due their action against different groups of microorganisms, such as bacteria (14, 15, 21, 35), yeast and fungi (1, 3, 4, 8, 9, 16, 18, 25, 28, 30, 33, 37, 42). Studies on coating of fruits and vegetables (6, 10, 11, 12, 13, 17) and defensive plant mechanism studies (39) have been described. However, most studies describing inhibitory effects on the growth of microorganisms involved poorly characterized chitosans or only one or a few different degrees of polymerization (DP) and fractions of acetylation (FA) of chitosans (3, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 25, 33). Thus, important information is lacking on the influence of DP and FA on the biological activity of chitosans against fungi of economic importance for post-harvest losses of fruits and vegetables. The phytopathogenic fungi evaluated in this study B. cinerea, P. expansum, R.stolonifer, and A. alternata, are responsible for strawberry (6, 9, 10), cucumber and bell pepper (11, 12), pear (22), apple (7), wheat (23), and tomato (3, 33) losses.

Growth of filamentous fungi is usually measured as an increase in dry mass (either stationary or shake flasks, and quantitative radial growth measurements on solid media. However, experiments testing the effect of several compounds on the growth of a fungus, can become very space-demanding and laborious, limiting the scale of studies.

The objective and novelty of this study was to examine the in vitro antifungal effect of fifteen chitosans with widely different DP and FA against the phytopathogenic fungi B. cinerea, P. expansum, R.stolonifer, and A. alternata, which are responsible for important economic losses in Brazilian fruit exports (citrus, strawberries, grapes, papaya, apples amongst others) and to overcome the difficulties related to the conventional methods to measure biomass content, by using the microtiter plate technique.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chitosan samples

Chitosan samples were classified into four groups, according to their source and treatment (Table 1). Details on preparation and characterization of all chitosan tested are described in Oliveira-Jr (27). Group I contained 3 chitosans with different DP and the same FA (the raw material was coded as A, from Polymar, Fortaleza, Brazil and was thermally depolymerized to produce samples B and C chitosans). Group II included 2 chitosans of same DP with different FA obtained from alkaline deacetylation of chitin (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, USA). Group III included chitosans with average DP of ca. 190, but FA varying from 0.01 to 0.69. Chitosans of this group were prepared by partial homogeneous de-N-acetylation of highly acetylated chitosan polymers as described previously by Vander et al. (39), and generously provided by Dr. Kjell M. VÅrum, Trondheim, Norway. The acetyl groups were distributed randomly along the linear polymer chains, and the polymers were all fully water soluble at slightly acidic pH. Group IV chitosans with a constant DP (obtained from mass average molar mass) of around 2,500 were prepared by re-N-acetylation of a fully de-N-acetylated chitosan polymer (Table 1) as described by Lamarque et al. (19) and were provided by Dr. Alain Domard, Lyon, France. The acetyl groups were distributed randomly along the linear polymer chains, and the polymers were all fully water soluble at slightly acidic pH.

Table 1.

Average degree of polymerization (DP) and fraction of acetylation (FA) of chitosans (Group I) without treatment (A) and thermally treated for 3 and 10 h (B and C) and chitosans (Group II) obtained by partial alkaline deacetylation of chitin (D and E) and chitosans (X1 to X6) generated by partial homogeneous de-N-acetylation of chitin (Group III) and chitosans (Y1 to Y4) obtained by partial re-N-acetylation of polyglucosamine (Group IV).

| Group III | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 | X5 | X6 |

| DP b | 190 | 320 | 68 | 121 | 210 | 224 |

| FA | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.35 | 0.49 | 0.60 | 0.69 |

| Group IV | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | Y1 | Y2 | Y3 | Y4 |

| DP a | 2,580 | 2,608 | 2,528 | 2,518 |

| FA | 0.10 | 0.29 | 0.40 | 0.50 |

DPw (mass average molar mass)

DPn (number average molar mass).

FA determined by potentiometric titration. FA of other samples were determined by high-field 1H NMR (proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy)

Microorganisms and cultivation

A. alternata (CCT 2816), P. expansum (CCT 4680), and R. stolonifer (CCT 2002) were purchased from André Tosello Foundation (Campinas, Brasil). B. cinerea, an isolate from grape, was provided by the Department of Botany of the University of Munster. B. cinerea and P. expansum were cultured on potato dextrose agar (PDA) and in malt extract agar (MEA) supplemented with 2% (m/v) each of glucose and peptone, while R. stolonifer and A. alternata were both cultured on MEA. In order to achieve sporulation, the fungi were incubated in Petri dishes (Ø = 9 cm) for 8 days for A. alternata, B. cinerea, and P. expansum, and for 4 days for R. stolonifer at 25°C at 100 cm under Hg lamps with a 12 h photoperiod. Water suspensions of spores and mycelia were filtered through cotton. The concentration of spores was assessed using a hemocytometer (Fuchs-Rosenthal Hell Linie) under optic microscopy (magnification 400×). The concentration of R. stolonifer spores was adjusted to 1 ´ 104 mL-1 and those of B. cinerea, A. alternata, and P. expansum to 2 ´ 104 mL-1.

Bioassays

Complete medium (CM), pH 4.3, was prepared as described by Pontecorvo (31), which contains approximately 6.2 g x L-1 carbon and 0.6 g x L-1 nitrogen, by considering the contribution of yeast extract, peptone, casein and sucrose). Aliquots (150 μL) of sterile CM containing the required volume of chitosan (2 mg × mL-1) for dose response and sterile water were dispensed into wells of 96-well polystyrene microtiter plates (Roth®) containing either 10 μL of a spore suspension of a test fungus or 10 μL of sterile water (blanks). All chitosan samples and concentrations tested against the phytopathogenic fungi used in this study are listed in Table 2. The plates were incubated at 25 °C under agitation, 200 o.p.m (orbits per minute), for up to three days for R. stolonifer, six days for B. cinerea and A. alternata, and five days for P. expansum. Fungal growth was assessed by measuring the optical density of the culture media at 405 nm at 24 h intervals for A. alternata, B. cinerea, and P. expansum and at 12 h intervals for R. stolonifer.

Table 2.

Chitosan samples and concentrations tested against the phytopathogenic fungi A. alternata, B. cinerea, P. expansum and R. stolonifer.

| Chitosan groups | Chitosan codes | Concentrations (µg × mL-1) | Fungi |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | A, B and C | 0, 20, 40, 60, 100, 200, 300, 400, 600, 800, 900 and 1,000 | A. Alternata, B. cinerea, P. expansum and R. stolonifer |

| II | D and E | ||

| III | X1, X2, X3, X4, X5 and X6 | 0, 60, 100, 200, 300, 400, 600, 700, 800 and 900 | A. Alternata and B. cinerea |

| IV | Y1, Y2, Y3 and Y4 |

Three independent experiments were carried out for each condition, and the data are reported as means ±S.D. Statistical analysis was carried out with the OriginPro version 8 program (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, Massachusetts, USA) and differences between the means were detected by the Tukey multiple comparison test. A standard curve was previously prepared to evaluate the correlation of absorbance values with dry weight of biomass, which was found to be linear for the range between zero and 4.0 for the fungi studied. According to Langvad (20), the absorbance measured in the microtiter plate reader is caused by light absorbance and light scattering.

Growth rate (GR) was calculated according to the following equation:

where,

AUMGC = area under mycelial growth curve (Aλ=405nm x day -1)

Xi = the absorbance at the time on the ith day

ti = the time in days of acessment on the ith day

n = the total number of observations

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was defined as the concentration of chitosan able to reduce GR values to zero.

Chitosans from Group I and from Group II were tested against all fungi studied and A. alternata and B. cinerea, were selected for further experimentation using Group III and Group IV chitosans. Therefore the antifungal activities of all chitosans were tested against A. alternata and B. cinerea, but only five chitosans were tested against P. expansum and R. stolonifer.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

Scanning electron microscopy was carried out according to Melo and Faull (24). In case of control suspension the hyphae were removed from the media by using a clamp and the suspension treated with chitosans was filtered in Millipore PTFE hydrophilic membrane, pore size 0.45μm and Æ=13mm (São Paulo, Brasil). Samples were fixed by immersion in 2.5%(v/v) glutaraldehyde in 0.1 mol L-1 sodium cacodylate buffer pH 7.0 for 1h, washed three times in 0.1 mol L-1 sodium cacodylate buffer pH 7.0, post-fixed with 1%(m/v) osmium tetroxide diluted in the same buffer for 1h. They were then washed three times with the same buffer pH. Subsequently they were dehydrated in a series of crescent concentrations of acetone (10, 25, 40, 60, 75, 85, 95 and 100%v/v) with 15min resting time in each solution. The materials were dried in a CO2 apparatus and sputter-coated with gold and viewed using a field emission scanning electron microscope, Leo 982 (Zeiss + Leica).

RESULTS

The growth curves (GC) of the filamentous fungi R. stolonifer, B. cinerea, P. expansum, and A. alternata showed that CM medium at pH 4.3 well suited the in vitro assays in the microtitre plates, within standard deviation values varying from 0.01 to 0.18 OD readings. It was also observed that 20% (v/v) of 40 mmol L-1 acetic acid in CM (pH 3.9-4.2) did not significantly affect fungal GR and that chitosans markedly inhibited or completely prevented the growth of all four fungi tested. A dose-response relationship was generally observed for each fungus, with average fungal GR decreasing when the concentration of chitosan increased.

Chitosans from Group I and from Group II were tested against all fungi studied and A. alternata and B. cinerea, were selected for further experimentation using Group III and Group IV chitosans. Therefore the antifungal activities of all chitosans were tested against A. alternata and B. cinerea, but only five chitosans were tested against P. expansum and R. stolonifer.

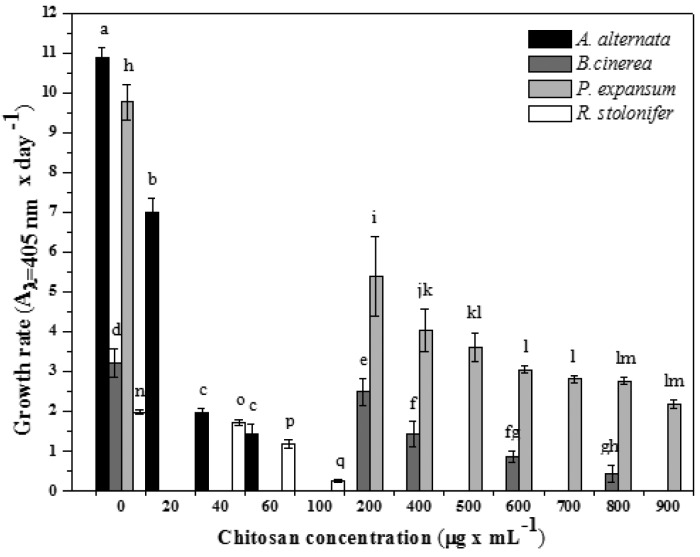

Figure 1 clearly shows the reduction of GR of A. alternata, from 10.91±0.23 to 1.44±0.26 Aλ=405nm x day -1 when the concentration of chitosan A increased from zero to 60 μg × mL-1 (MIC=100 μg × mL-1). The sensitivity of the fungi against chitosan varied according to the strain, and is well depicted in this figure. The GR of B. cinerea, was significantly reduced with higher concentrations of chitosan A (900 μg × mL-1), from 3.22±0.35 to 0.45±0.21 Aλ=405nm x day -1 and this reduction of GR values by the increase of chitosan concentration was similarly observed for the other fungi, P. expansum being the less susceptible in the presence of chitosan A, whose GR reduced from 9.78±0.44 to 2.17±0.11 Aλ=405nm x day -1.

Figure 1.

Growth rate of A. alternata, B. cinerea, P. expansum and R. stolonifer in presence of different concentrations of chitosan A (group I). a–qMeans for the same fungus with different letters differ significantly (p ≤ 0.05) according to the Tukey test.

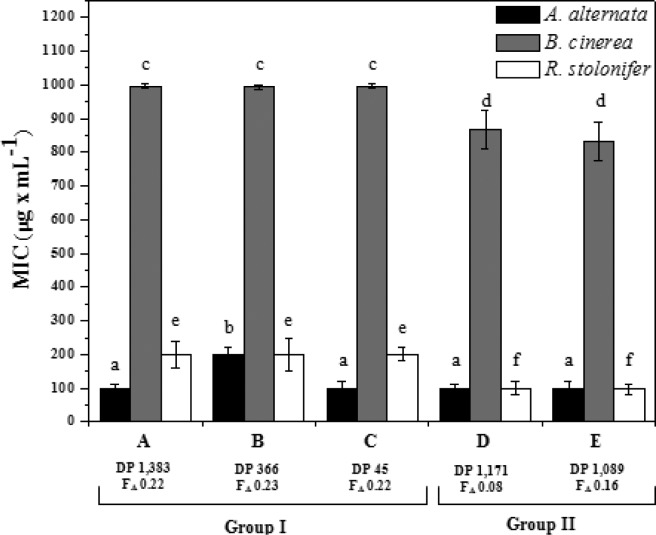

Figure 2 shows the MIC values for Groups I and II chitosans. Chitosans with a constant FA of ca. 0.22 but different DPs ranging from ca. 1,400 to 45, showed different antifungal activities against A. alternata, whose MICs were variable with decreasing DP. In contrast, the sensitivities of B. cinerea (MIC = 1,000 μg × mL-1) and R. stolonifer (MIC = 200 μg × mL-1) did not depend on the DP of these chitosans.

Figure 2.

Minimum inhibitory concentrations of chitosans (Group I) A, B, and C with different DP (degree of polymerization) and chitosans (Group II) D and E with different FA (fraction of acetylation) against A. alternata, B. cinerea, and R. stolonifer. a–fMeans for the same fungus specie with different letters differ significantly (p ≤ 0.05) according to the Tukey test.

Group II chitosans, with a constant DP of ca. 1,100 but different FA of 0.08 and 0.16, exhibited equal antifungal activities, with MICs of 100 μg × mL-1 for A. alternata and for R. stolonifer, and 900 μg × mL-1 for B. cinerea. Chitosans D and E did not completely inhibit the growth of P. expansum (data not shown), but their inhibitory effects were stronger than those of chitosan A from Group I. Therefore, the inhibitory effects of chitosans from Group I and Group II tended to increase with decreasing DP but were not markedly influenced by FA of 0.08 to 0.22. In all cases, A. alternata and R. stolonifer were more sensitive to chitosan than B. cinerea and P. expansum. The less susceptible fungus, P.expansum was found to require concentrations of chitosans A, D and E higher than 900 μg × mL-1, whose MIC values could not be calculated (data not shown).

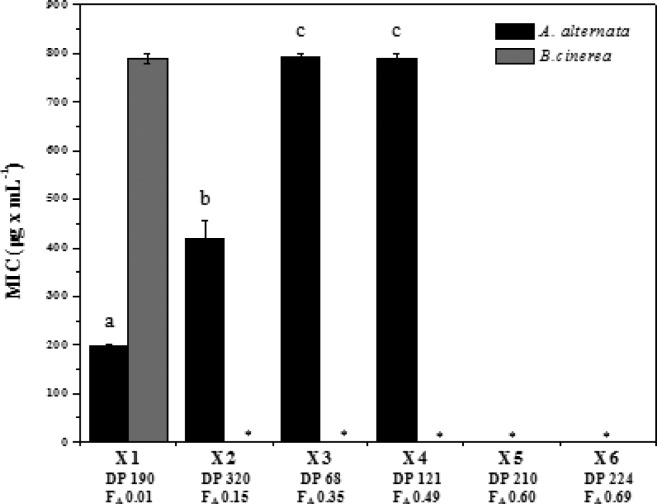

The inhibitory effects of Group III chitosans, within similar DP (about 200) and FA varying from 0.01 to 0.69 were evaluated against B. cinerea and A. alternata (Figure 3). Only chitosan X1 (lowest FA= 0.01) completely inhibited GR of B. cinerea, with a MIC of 800 μg × mL-1; complete inhibition was not obtained with the other chitosans of this group, up to concentration 800 μg × mL-1. In contrast, growth of A. alternata was completely suppressed by chitosans X1 to X4, (FA varied from 0.01 to 0.49) with increasing MICs. Again, complete inhibition was not obtained with samples X5 and X6 (FA 0.060 and 0.69, respectively) using the maximum concentration of 800 μg × mL-1. Clearly, the antifungal activity of the Group III chitosans increased with decreasing FA for both fungi and it was again observed that A. alternata was more sensitive than B. cinerea to chitosans.

Figure 3.

Minimum inhibitory concentrations of chitosans X1 to X6 (Group III) generated by partial homogeneous de-N-acetylation of chitin with similar DP and different FA against A. alternata andB. cinerea. *MICs were not obtained for the chitosans against the fungi tested. a-c Means for the same fungus specie with different letters differ significantly (p ≤ 0.05) according to the Tukey test.

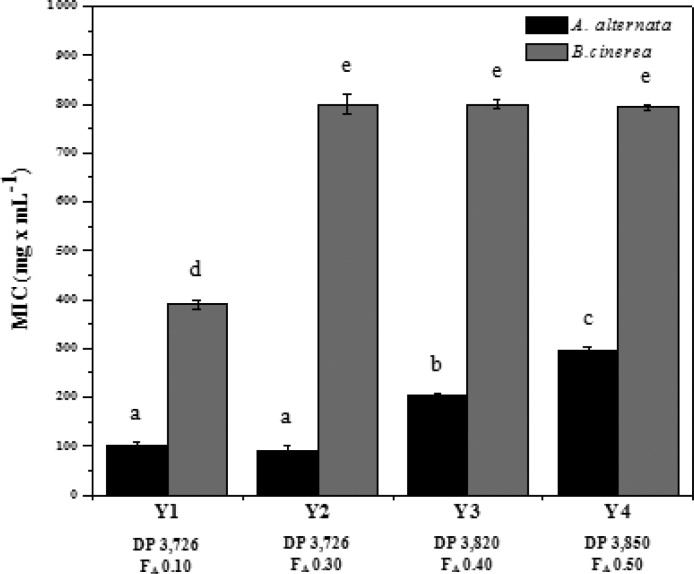

The inhibitory effects of the Group IV chitosans (similar DP of about 2,500 and FA from 0.10 to 0.50) against B. cinerea and A. alternata can be seen in Figure 4. All chitosans were able to completely inhibit GR of both B. cinerea and A. alternata and MIC values could be calculated. Their inhibitory activity again increased with a decrease in FA and A. alternata was found to be more sensitive than B. cinerea. Although the same trend in antifungal activities as that obtained with Group III chitosans was also noticed with Group IV chitosans, Group IV chitosans were more active than Group III chitosans.

Figure 4.

Minimum inhibitory concentrations of chitosans Y1 to Y4 (Group IV) obtained by partial re-N-acetylation of polyglucosamine with similar DP and different FA against A. alternata and B. cinerea. a–eMeans for the same fungus specie with different letters differ significantly (p ≤ 0.05) according to the Tukey test.

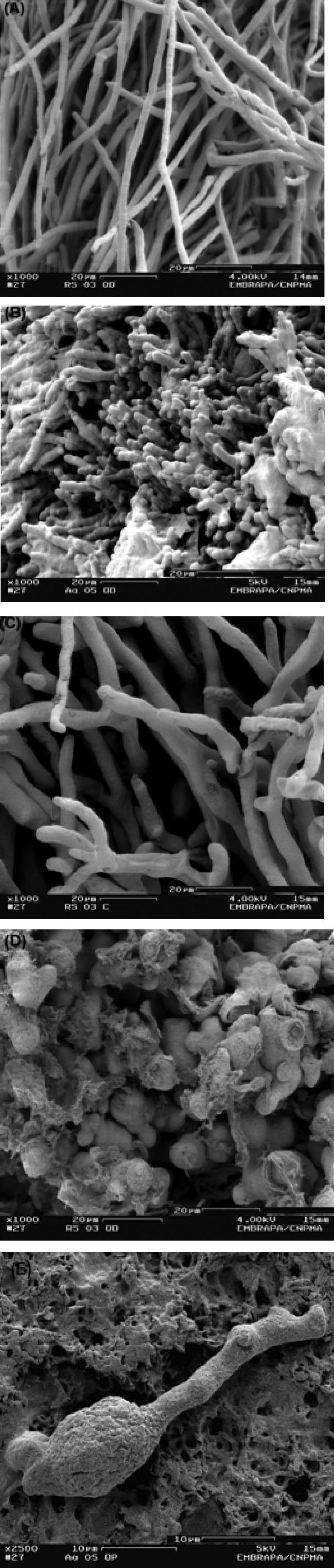

Changes in fungal morphology due to the effect of chitosan

Chitosans were not only effective in restricting mycelial growth of A. alternata, B. cinerea, P. expansum, and R. stolonifer, but also induced marked morphological changes such as general excessive mycelial branching and hyphal size reduction and aggregation. Morphological anomalies caused by coating on the mycelia surface of the fungi studied suggest that chitosan layer around the surface may make nutrient transport difficult. In the case of A. alternata and B. cinerea, abnormal shapes and swelling of the mycelia were observed in addition to the morphological changes, and also germ tube inhibition was found for A. alternata (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Scanning electron micrographs of mycelia of A. alternata (A) in the absence of chitosan, A. alternata (B) treated with 500 µg × mL-1 chitosan A (DP 1,089 and FA 0,16); R. stolonifer (C) in the absence of chitosan and R. stolonifer (D) treated with 500 µg × mL-1 chitosan A (DP 1,089 and FA 0,16). Magnification 1,000×. (E) Spore and germ tube of Alternaria alternata after 5 days of culture at 25 °C with medium amended with chitosan P (1,000 mg × mL-1). Magnification at 2,500×.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

We have previously adapted the microtiter plate technique in our laboratory to study the antimicrobial activity of chitosan against plant pathogenic bacteria and fungi, now it has been extended to this study on the growth of four fungi causing post-harvest damage to fruits and vegetables, in the absence or presence of up to fifteen different chitosans varying greatly in their DP and FA. The present study corroborates our earlier observations (not published), namely that the antifungal activities of chitosans depend on both of these parameters, by employing the technique validated by Langvad (20). Our study here shows the advantage of miniaturization of analytical tools to evaluate GR and MIC of the four fungi, since conventional techniques require larger volumes of materials, samples, reagents, and are more time consuming.

The effect of FA is best seen in chitosans of Group III and Group IV which span a wide range of FA from ca. 0 to 0.7 in both cases, the antimicrobial activity of the chitosans decreased with increasing FA. Consequently, fully de-acetylated polyglucosamine exhibited the highest antifungal activities. This effect was previously observed by Pacheco et al. (28) who have only evaluated a series of five different chitosans against the fungus P.digitatum.

The effect of DP is less unambigious. Group I chitosans with a low FA and spanning a DP range from 45 to ca. 1,400 clearly demonstrate that the antifungal activity increases with decreasing molecular weight. This is in accordance with our previous study (27) where the same trend was clearly seen with a series of polyglucosamines spanning a DP range from 20 to 2,500. However, when comparing the activities of chitosans of Group III and Group IV chitosans, the high DP chitosans (Group IV) were clearly more active than their low DP counterparts. The DP-dependent difference in inhibitory activity was more pronounced the higher the FA of the chitosans in both studies. Considering this, we think that there is a possibility that the DP dependency of the inhibitory activity of chitosans changes with FA, while highly de-acetylated chitosans exhibit their inhibitory activity best as small to medium sized polymers, the inhibitory activity of highly acetylated chitosans may be highest at very large polymer sizes. We are currently generating a series of chitosans with a constant high FA and spanning a DP range from small to very large polymers to investigate this possibility.

The relationship between DP of chitosans and chito-oligosaccharides and their antifungal activity has been investigated in some studies (3, 16, 25, 26, 28, 37, 38, 42). Few studies reported on the effect of FA on the antifungal activity of chitosans, and even fewer on combined effects of both parameters (28).

Oligosaccharides of DP 9 and DP 14 which had been prepared by nitrous acid depolymerization of chitosan were active against Leptographium procerum and Sphaeropsis sapinea, but not against Trichoderma harzianum, while oligomers of DP 5 were inactive (37). On the other hand, Fusarium solani was inhibited by chitooligosaccharides of DP ≥ 7, while oligomers of DP 2 and DP 8 were not active against three Fusarium species (38). Low-DP chitosans, in particular chitooligosaccharides with an average DP 20, were more effective than high-DP chitosans in inhibiting mycelial growth of a variety of phytopathogenic and wood inhabiting fungi (16, 38, 42). Different methods of chitosan preparation had a significant effect on the DP and FA of the resulting biopolymers and thereby, their antimicrobial activities (28).

Oliveira-Jr et al. (26) have observed that chitooligosaccharides of DP ≤ 8 are not notably inhibitory to any of the fungi, A. alternata, B. cinerea, P. expansum, and R. stolonifer and high-DP chitooligosaccharides (DP ≤ 12) showed initially inhibitory effects. However, the complete inhibition for all fungi was not obtained by using chitooligosaccharides. In contrast, as reported in our present study, A. alternata, B. cinerea e R. stolonifer were completely inhibited and growth reduction for P. expansum was observed by high-DP chitosans (DP 45 to 2,608). Higher antibacterial activity of chitosan compared with chitosan oligomers also was reported by several workers (32, 34, 38).

The novelty of our studies is that the antimicrobial activities of a very wide variety of chitosans against different fungi, including species belonging to different taxonomic groups, namely is described here. While the growth of all of them was inhibited to some extent by the presence of chitosans, their sensitivity varied greatly. However, the relative antifungal activities of different chitosans were similar for all fungi studied, so that a general mechanism appears to be responsible for the observed growth inhibition.

The exact mechanism by which the higher chitooligosaccharides and chitosans exert antimicrobial activity is unknown. Based on the other author´s observation that the fungistatic activity is higher at lower pH, it was assumed that the toxicity is correlated, besides to optimum DP, to the cationic charge of the oligosaccharides (37). Our studies indicate that reasons also can be important for the growth rate inhibitions, i.e. enzymatic uptake of simple carbohydrates by permeases could temporally be blocked by the presence of the large oligosaccharides (27). Several fungi systems however, such as cellulase containing, are usually controlled by inducers, and glucose or catabolite repression, and the expression of enzymes to hydrolyze larger molecules to soluble oligosaccharides (low DP). After cellulose and large molecules are degraded a large amount of glucose is liberated, which causes catabolite repression (36). Chitin hydrolyzing enzymes could be similarly regulated, controlled by inducers and short chain molecules. Amaretti et al. (2) have demonstrated carbohydrate preferences in bacteria resulting from different distributions of carbon fluxes through the fermentative pathway, where substrate selectivity was observed based on the degree of polymerization, when shorter saccharides were the first to be consumed, while a delay was observed until longer oligosaccharides were utilized.

A number of possible mechanisms for the antimicrobial action of chitosan have been proposed, mostly based on the positive charge conferred by protonation of free amino groups at acidic pH, although the exact mechanism of action is still unknown. A polycationic chitosan or oligomer can potentially interact with negatively charged fungal cell membrane components (i.e., proteins, phospholipids), thus interfering with the normal growth and metabolism of the fungal cells (4, 13, 34). Roller and Covill (32) reported that amino groups in chitosan have the ability to interact with a multitude of anionic groups on the yeast cell wall surface, thereby forming an impervious layer around the cell. Because of its property to form films, chitosan may thus act as a barrier (i.e. anionic groups) and consequently, reducing their availability to a level that will not sustain growth of the pathogen (4). Our results suggest that this barrier to water soluble nutrients may be most effective for chitosans of lower molar mass and low FA, since we also have observed (40) that the water permeability of chitosan films is 50% reduced when molar mass of the original chitosan is reduced from 235 kDa (DP 1,383) to approximately 13.7 kDa (DP 45).

In conclusion, in the present study we have shown that the combined effects of FA and DP are important variables in the bioactivity of chitosans. The chitosan coating on the surface of the mycelia and severe structural alterations in the fungal mycelia, observed by scanning electron microscopy, suggest that fungal growth inhibition could be explained by the direct interaction of chitosan on the fungal cell wall. Results of this study indicate that chitosan samples with low FA were most effective against the phytopathogenic fungi tested, while chitosan with high FA did not have the ability to inhibit fungal growth in vitro. Complete inhibition was obtained for the fungi B. cinerea, R. stolonifer, and A. alternata, and growth reduction for P. expansum, using chitosan samples with different FA and DP.

Acknowledgments

Financial support by the Brazilian funding agencies FAPESP, CAPES and CNPq is gratefully acknowledged, as also to the PROBRAL programme (CAPES/DAAD) and to the European Commission (ALFA Programme, II-0259-FA-FC POLYLIFE). We also acknowledge K.M.VÅrum and A.Domard for supplying chitosans, as also prof. M.G. Peter for the NMR characterization of groups I and II chitosans.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allan C.R., Hadwiger L.A. The fungicidal effect of chitosan on fungi of varying cell composition. Exp. Mycol. 1979;3:285–287. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amaretti A., Bernardi T., Tamburini E., Zanoni S., Lomma M., Matteuzzi D., Rossi M. Kinetics and metabolism of Bifidobacterium adolescentis MB 239 growing on glucose, galactose, lactose, and galactooligosaccharides. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;11:3637–3644. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02914-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Badawya M. E. I., Rabea E. I. Potential of the biopolymer chitosan with different molecular weights to control postharvest gray mold of tomato fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2009;51:110–117. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bautista-Baños S., Hernandez-Lauzardo A.N., Velázquez-del Valle M.G., Hernández-López M., Bravo-Luna L., Ait Barka E., Bosquez-Molina E., Wilson C.L. Chitosan as a potential natural compound to control pre and postharvest diseases of horticultural commodities. Crop Prot. 2006;25:108–118. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beales N., Smith J. Antimicrobial Preservative-Reduced Foods. In: Smith J., editor. Technology of Reduced Additive Foods. London, England: Wiley; 2007. pp. 84–105. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhaskara Reddy M.V., Belcacemi K., Corcuff R., Castaigne F., Arul J. Effect of pre-harvest chitosan sprays on post-harvest infection by Botrytis cinerea and quality of strawberry fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2000;20:39–51. [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Capdeville G., Wilson C. L., Beer S. V., Aist J. R. Alternative disease control agents induce resistance to blue mold in harvested ‘Red Delicious’ apple fruit. Phytopathology. 2002;92:900–908. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2002.92.8.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El Ghaouth A., Arul J., Asselin A., Benhamou N. Antifungal activity of chitosan on postharvest pathogens: Induction of morphological and cytological alterations in Rhizopus stolonifer. Mycol. Res. 1992;96:769–779. [Google Scholar]

- 9.El Ghaouth A., Arul J., Grenier J., Asselin A. Antifungal activity of chitosan on two postharvest pathogens of strawberry fruits. Phytopathology. 1992;82:398–402. [Google Scholar]

- 10.El Ghaouth A., Arul J., Ponnampalam R., Boulet M. Chitosan coating effect on storability and quality of fresh strawberries. J. Food Sci. 1991;56:1618–1620. [Google Scholar]

- 11.El Ghaouth A., Arul J., Ponnampalam R., Boulet M. Use of chitosan coating to reduce water loss and maintain quality of cucumber and bell pepper fruits. J. Food Process. Preservat. 1991;15:359–368. [Google Scholar]

- 12.El Ghaouth A., Arul J., Wilson C., Benhamou N. Biochemical and cytochemical aspects of the interactions of chitosan and Botrytis cinerea in bell pepper fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 1997;12:183–194. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fang S.W., Li C.F., Shih D.Y.C. Antifungal activity of chitosan and its preservative effect on low sugar candied kumquat. J. Food Prot. 1994;56:136–140. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-57.2.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujimoto T., Tsuchiya Y., Terao M., Nakamura K., Yamamoto M. Antibacterial effects of Chitosan solution against Legionella pneumophila, Escherichia coli, and Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2006;112:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gil G., del Monaco S., Cerrutti P., Galvagno M. Selective antimicrobial activity of chitosan on beer spoilage bacteria and brewing. Biotechnol. Lett. 2004;26:569–574. doi: 10.1023/b:bile.0000021957.37426.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirano S., Nagao N. Effects of chitosan, pectic acid, lysozyme and chitinase on the growth of several phytopathogens. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1989;53:3065–3066. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang Y.M., Li Y.B. Effects of chitosan coating on postharvest life and quality of longan fruit. Food Chem. 2001;73:139–143. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kendra D.F., Hadwiger L.A. Characterization of the smallest chitosan oligomer that is maximally antifungal to Fusarium solani and elicits pisatin formation by Pisum sativum. Exp. Mycol. 1984;8:276–281. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lamarque G., Lucas J.M., Viton C., Domard A. Physicochemical behavior of homogeneous series of acetylated chitosans in aqueous solution: Role of various structural parameters. Biomacromolecules. 2005;6(1):131–142. doi: 10.1021/bm0496357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langvad F. A rapid and efficient method for growth measurement of filamentous fungi. J. Microbiol. Methods. 1999;37:97–100. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(99)00053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu H., Du Y., Wang X., Sun L. Chitosan kills bacteria through cell membrane damage. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2004;95:147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2004.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mari M., Iori R., Leoni O., Marchi A. Bioassays of glucosinolate-derived isothiocuanates against postharvest pear pathogens. Plant Pathol. 1996;45:753–760. [Google Scholar]

- 23.McRoberts N., Lennard J. H. Pathogen behaviour and plant cell reactions in interactions between Alternaria species and leaves of host and nonhost plants. Plant Pathol. 1996;45:742–752. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Melo I. S., Faull J. L. Scanning electron microscopy of conidia of Thichoderma stromaticum, a biocontrol agent of witches broom disease of cocoa. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2004;35:330–332. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meng X., Yang L., Kennedy J. F., Tian S. Effects of chitosan and oligochitosan on growth of two fungal pathogens and physiological properties in pear fruit. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010;81:70–75. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oliveira-Jr E.N., El Gueddari N.E., Moerschbacher B.M., Peter M.G., Franco T.T. Growth of Phytopathogenic Fungi in the Presence of Partially Acetylated Chitooligosaccharides. Mycopathologia. 2008;166:163–174. doi: 10.1007/s11046-008-9125-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oliveira-Jr. E.N. Caracterização dos efeitos de quitosanas na inibição de fungos fitopatogênicos. Brasil: Campinas; 2006. p. 147. (PhD. Thesis. School of Chemical Engineering. UNICAMP) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pacheco N., Larralde-Corona C.P., Sepulveda J, Trombotto S., Domard A., Shirai K. Evaluation of chitosans and Picchia guillermondii as growth inhibitors of Penicillium digitatum. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2008;43:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peter M.G. Chitin and chitosan from animal sources. In: Vandamme E.J., De Baets S., Steinbüchel A., editors. Biopolymers, Polysaccharides II: Polysaccharides from Eukaryotes. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH; 2002. pp. 481–574. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Placencia-Jatomea M., Viniegra G., Olayo R., Castillo-Ortega M.M., Shirai K. Effect of chitosan and temperatura on spore germination on Aspergillus niger. Macromol. Biosci. 2003;3:582–586. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pontecorvo G. The genetics of Aspergillus nidulans. Adv.Genet. 1953;5:150–151. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2660(08)60408-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roller S., Covill N. The antifungal properties of chitosan in laboratory media and apple juice. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 1999;47:67–77. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(99)00006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sánchez-Domínguez D., Ríos M. Y., Castillo-Ocampo P., Zavala-Padilla G., Ramos-García M., Bautista-Baños S. Cytological and biochemical changes induced by chitosan in the pathosystem Alternaria alternata–tomato. Pest. Biochem. Physiol. 2011;99:250–255. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shahidi F., Arachchi J.K.V., Jeon Y.J. Food applications of chitin and chitosans. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 1999;10(2):37–51. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sudharshan N. R., Hoover D.G., Knorr D. Antibacterial action of chitosan. Food Biotechnol. 1992;6:257–272. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suto M., Tomita F. Induction, catabolite repression mechanisms of cellulase in fungi. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2001;92:305–311. doi: 10.1263/jbb.92.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Torr K.M., Chittenden C., Franich R.A., Kreber B. Advances in understanding bioactivity of chitosan and chitosan oligomers against selected wood-inhabiting fungi. Holzforschung. 2005;59:559–567. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Uchida Y., Izume M., Ohtakara A. Preparation of chitosan oligomers with purified chitosanase and its application. In: Skjåk-BrÆk G., Anthonsen T., Sandford P., editors. Chitin and chitosan: sources, chemistry, biochemistry, physical properties and applications. London, England: Elsevier; 1988. pp. 373–382. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vander P., Varum K.M., Domard A., El Gueddari N.E., Moerschbacher B.M. Comparison of the ability of partially N-acetylated chitosans and chitooligosaccharides to elicit resistance reactions in wheat leaves. Plant Physiol. 1998;118:1353–1359. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.4.1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoshida C.M.P., Oliveira-Jr E.N., Franco T.T. Chitosan tailor-made films: the effects of additives on barrier and mechanical properties. Packing Technol. Sci. 2008;22:161–170. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu T., Li H.Y., Zheng X.D. Synergistic effect of chitosan and Cryptococcus laurentii on inhibition of Penicillium expansum infections. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007;14:261–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang M., Tan T., Yuan H., Rui C. Insecticidal and fungicidal activities of chitosan and oligo-chitosan. J. Bioact. Compat. Polym. 2003;18:391–400. [Google Scholar]