Abstract

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the presence of the periodontal pathogens that form the red complex (Tannerella forsythia, Porphyromonas gingivalis and Treponema denticola) and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans in patients with chronic periodontitis. The sample consisted of 29 patients with a clinical and radiographic diagnosis of chronic periodontitis based on the criteria of the American Academy of Periodontology (3). Samples for microbiological analysis were collected from the four sites of greatest probing depth in each patient, totaling 116 samples. These samples were processed using conventional polymerase chain reaction, which achieved the following positive results: 46.6% for P. gingivalis, 41.4% for T. forsythia, 33.6% for T. denticola and 27.6% for A. actinomycetemcomitans. P. gingivalis and T. forsythia were more prevalent (p < 0.05) in periodontal pockets ≥ 8 mm. The combinations T. forsythia + P. gingivalis (23.2%) and T. forsythia + P. gingivalis + T. denticola (20.0%) were more frequent in sites with a probing depth ≥ 8 mm. Associations with the simultaneous presence of A. actinomycetemcomitans + P. gingivalis, A. actinomycetemcomitans + T. forsythia, P. gingivalis + T. forsythia and T. forsythia + T. denticola were statistically significant (p < 0.05). It was concluded that the red complex pathogens are related to chronic periodontitis, presenting a higher occurrence in deep periodontal pockets. Moreover, the simultaneous presence of these bacteria in deep sites suggests a symbiotic relationship between these virulent species, favoring, in this way, a further progression of periodontal disease.

Keywords: periodontitis, pathogens, Tannerella forsythia, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Treponema denticola, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans

INTRODUCTION

Periodontal disease affects a large number of individuals around the world (2) and is a major oral health problem both in developed and developing countries (12). Periodontitis is defined as a chronic inflammatory disease that affects the tooth-supporting tissues and bacterial deposits play an essential role in the pathogenesis of this condition 18, 22, 25).

Strong associations between periodontal disease and certain microorganisms have been reported in the literature, especially with regard to the presence of certain gram-negative anaerobic bacteria, such as A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, T. forsythia and T. denticola (6, 12, 17, 18, 19, 21, 24, 27). These organisms express potential virulence factors and induce host inflammatory mediators, eventually leading to the breakdown of connective tissue and alveolar bone resorption (20, 23, 27).

The literature suggests that the distribution and prevalence of periodontal pathogens vary depending on geographic locations as well as among different ethnic groups (9, 10, 12, 16, 24, 27). Such differences in global distribution place some populations at greater risk for infection and periodontal disease than others and this variation could be important to the epidemiology and treatment of periodontal disease (9).

In Brazil, few studies have been conducted to investigate the periodontal microbiota, most of these being conducted in the State of São Paulo (7, 8, 9, 13, 14, 15, 26). In these investigations, the bacteria P. gingivalis had its prevalence ranging from 17.8% to 90%, T. forsythia 33.3% to 100%, A. actinomycetemcomitans 23% to 90% and T. denticola was only investigated by Avila-Campos and Velásquez-Meléndez (7) with 60% of positive samples. In view of the importance of knowledge on the microorganisms that make up the subgingival microbiota and the limited number of studies involving South American populations, the aim of the present study was to identify the occurrence of the periodontal pathogens P. gingivalis, T. forsythia, T. denticola and A. actinomycetemcomitans in a convenience sample composed of adult Brazilian, nonsmokers with chronic periodontitis in the city of Recife (northeastern Brazil).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants and clinical examination

The present experimental, quantitative study was conducted at the dental clinic of the Postgraduate Dentistry Program, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco (UFPE), located in the city of Recife, state of Pernambuco, northeastern Brazil. A convenience sample comprised of 12 male and 17 female patients diagnosed with chronic periodontitis who sought dental treatment between August 2008 and July 2009 participated in this study. After an explanation of the objectives, the participants signed terms of informed consent. The study received approval from the UFPE Ethics Committee under process n°191/2008.

The following were the inclusion criteria: presence of least 20 natural teeth; age at least 30 years; clinical and radiographic diagnosis of chronic periodontitis (American Academy of Periodontology, 1999) (3), where to be considered as having chronic periodontitis patients should have at least one site with probing depth (PD) and clinical attachment loss (PIC) ≥ 4 mm; and voluntary agreement to participate. The following were the exclusion criteria: smoking habits; any systemic condition that might affect the progression of periodontal disease (diabetes, hypertension, autoimmune disease, etc.); pregnancy or nursing; periodontal therapy or use of antibiotics in previous six months; chronic use of anti-inflammatory drug; HIV positivity; and use of orthodontic appliance.

The following information on each patient was recorded: visible plaque index (Ainamo and Bay) (1), bleeding index (Ainamo and Bay) (1), probing depth and clinical attachment loss. The examination was performed by a single calibrated examiner in an office with artificial light using a dental mirror and Williams periodontal probe (Trinity ®, Brazil). The diagnosis of chronic periodontitis was based on the criteria established by the American Academy of Periodontology (4), which state that the patient must have at least one site with a probing depth and clinical attachment loss ≥ 4 mm. Subgingival plaque samples

The four sites of greatest probing depth in each patient were used to obtain subgingival samples, totaling 116 samples. Sterilized n° 30 paper tips (Dentsply, Brazil) were inserted to the depth of the pocket, left in place for 20 seconds, transferred to microcentrifuge tubes and stored at -20 C for subsequent DNA extraction and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis at the Molecular Biology Laboratory of the Postgraduate Dentistry Program, UFPE.

DNA extraction

DNA from subgingival clinical samples was isolated using the Geneclean kit (Qbiogene, Inc.), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

PCR detection

The amplification reaction was performed with a total volume of 25 μl, containing 1.3 μl of MgCl2 (50 mM) (LGC Biotecnologia, Brazil), 2.5 μl of dNTP (2 mM) (LGC Biotecnologia, Brazil), 1 μl of each primer (10 mM) (Invitrogem ®, Brazil), 2.5 μl of 10X PCR buffer (LGC Biotecnologia, Brazil), 0.2 μl of Taq DNA polymerase (5 U/μl) (LGC Biotecnologia, Brazil), 13.5 μl of sterile Milli-Q water and 3 μl of DNA sample. At each run, an amplification reaction without the DNA sample was used as the negative control to check the possibility of contamination. The primers used for PCR were species-specific for 16S rDNA. The sequence used was based on Ashimoto et al. (5). The thermocycler (Biocycle) program and the annealing temperature was also based on Avila-Campos and Velasques-Meléndez (7) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Microorganisms and specific primers for PCR.

| Microorganism | Primer (5’-3’) | PCR annealing temperature | Extension of amplicon (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A actinomycetemcomitans | F - GCT AAT ACC GCG TAG AGT CGG | 50°C | 557 |

| R - ATT TCA CAC CTC ACT TAA AGG T | |||

| P. gingivalis | F - AGG CAG CTT GCC ATA CTG CG | 60° C | 404 |

| R - ACT GTT AGC AAC TAC CGA TGT | |||

| T. forsythia | F - GCG TAT GTA ACC TGC CCG CA | 60° C | 641 |

| R - TGC TTC AGT GTC AGT TAT ACC T | |||

| T. denticola | F - TAA TAC CGA ATG TGC TCA TTT ACA T | 60° C | 316 |

| R- TCA AAG AAG CAT TCC CTC TTC TTC TTA |

The PCR products (9.5 μl) were added to 0.5 μl of blue green fluorescence (LGC Biotecnologia, Brazil) and submitted to electrophoresis in 1.5% agarose gel. The gels were then visualized and photographed on a UV transilluminator for later analysis. A 100-bp DNA ladder (LGC Biotecnologia, Brazil) was used as the molecular mass standard. All samples negative for pathogens were repeated and confirmed.

Statistical Analysis

Analysis was performed using descriptive statistics (frequency, mean, mode, median) and the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, when the conditions for using the chi-square did not apply. A 5% level of significance and 95% confidence interval were used for all statistical tests.

RESULTS

Patient age ranged from 30 to 59 years (mean: 41.8 years). More than half the patients (58.6%) were female. Regarding the sites evaluated, 74.1% of samples were collected from posterior teeth. Most (76.7%) exhibited bleeding upon probing, 37.9% had a probing depth of 6 to 7 mm and only 31.9% had visible dental plaque (Table 2).

Table 2.

Evaluation of the tooth, plaque, bleeding and probing depth

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| • Dental Element | ||

| Anterior | 30 | 25.9 |

| Posterior | 86 | 74.1 |

| • Bleeding | ||

| Positive | 89 | 76.7 |

| Negative | 27 | 23.3 |

| • Plaque | ||

| Positive | 37 | 31.9 |

| Negative | 79 | 68.1 |

| • Probing depth (mm) | ||

| ≤3 | 3 | 2.6 |

| 4 a 5 | 39 | 33.6 |

| 6 a 7 | 44 | 37.9 |

| ≥8 | 30 | 25.9 |

| TOTAL | 116 | 100.0 |

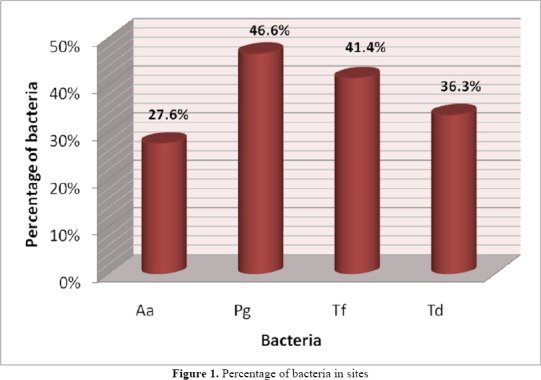

Among the 116 collection sites, 46.6% were positive for P. gingivalis, 41.4% were positive for T. forsythia, 33.6% were positive for T. denticola and 27.6% were positive for A. actinomycetemcomitans (Figure 1). There were no significant associations (p > 0.05) between these bacteria and gender, age, bleeding upon probing or visible dental plaque.

Figure 1.

Percentage of bacteria in sites

Significant associations were found between probing depth and the bacteria P. gingivalis and T. forsythia (p < 0.05), demonstrating that these bacteria were more prevalent in deep pockets (≥ 8 mm), followed by sites with probing depths of 6 to 7 mm (Table 3). Table 4 displays the occurrence bacteria either isolated or combined according to probing depth. At sites with a probing depth ≥ 8 mm, the two most frequent combinations were P. gingivalis + T. forsythia (23.2%) and T. forsythia + P. gingivalis + T. denticola (20.0%).

Table 3.

Evaluation of bacteria at sites according to probing depth.

| Probing depth (mm) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | ≤3 | 4 to 5 | 6 to 7 | ≥8 | Total Group | p-value | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | N | % | ||

| • A. actinomycetemcomitans | |||||||||||

| Positive | 1 | 33.3 | 8 | 20.5 | 13 | 29.5 | 10 | 33.3 | 32 | 27.6 | p(†) = 0.591 |

| Negative | 2 | 66.7 | 31 | 79.5 | 31 | 70.5 | 20 | 66.7 | 84 | 72.4 | |

| • P. gingivalis | |||||||||||

| Positive | 1 | 33.3 | 9 | 23.1 | 21 | 47.7 | 23 | 76.7 | 54 | 46.6 | p(†) < 0.001* |

| Negative | 2 | 66.7 | 30 | 76.9 | 23 | 52.3 | 7 | 23.3 | 62 | 53.4 | |

| • T. forsythia | |||||||||||

| Positive | – | – | 12 | 30.8 | 16 | 36.4 | 20 | 66.7 | 48 | 41.4 | p(†) = 0.005* |

| Negative | 3 | 100.0 | 27 | 69.2 | 28 | 63.6 | 10 | 33.3 | 68 | 58.6 | |

| T. denticola | |||||||||||

| Positive | – | – | 12 | 30.8 | 15 | 34.1 | 12 | 40.0 | 39 | 33.6 | p(†) = 0.660 |

| Negative | 3 | 100.0 | 27 | 69.2 | 29 | 65.9 | 18 | 60.0 | 77 | 66.4 | |

| TOTAL | 3 | 100.0 | 39 | 100.0 | 44 | 100.0 | 30 | 100.0 | 116 | 100.0 | |

significant difference at 5.0%

Fisher’s exact test

Table 4.

Assessment of isolated or combined bacteria in sites according to probing depth

| Probing depth (mm) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | ≤3 | 4 to 5 | 6 to 7 | ≥8 | Total Group | |||||

| N | % | n | % | N | % | n | % | n | % | |

| None | 2 | 66.7 | 18 | 46.2 | 15 | 34.1 | 2 | 6.7 | 37 | 31.9 |

| A. actinomycetemcomitans | – | – | 1 | 2.6 | 2 | 4.5 | 1 | 3.3 | 4 | 3.4 |

| P. gingivalis | – | – | – | – | 2 | 4.5 | 2 | 6.7 | 4 | 3.4 |

| T. forsythia | – | – | 1 | 2.6 | 1 | 2.3 | 1 | 3.3 | 3 | 2.6 |

| T. denticola | – | – | 5 | 12.8 | 3 | 6.8 | – | – | 8 | 6.9 |

| A. actinomycetemcomitans + P. gingivalis | 1 | 33.3 | – | – | 2 | 4.5 | 3 | 10.0 | 6 | 5.2 |

| A. actinomycetemcomitans + T. forsythia | – | – | 1 | 2.6 | – | – | 1 | 3.3 | 2 | 1.7 |

| P. gingivalis + T. forsythia | – | – | 4 | 10.3 | 4 | 9.1 | 7 | 23.3 | 15 | 12.9 |

| P. gingivalis + T. denticola | – | – | 1 | 2.6 | 3 | 6.8 | 1 | 3.3 | 5 | 4.3 |

| T. forsythia + T. denticola | – | – | 1 | 2.6 | 1 | 2.3 | 1 | 3.3 | 3 | 2.6 |

| A. actinomycetemcomitans + P. gingivalis + T. forsythia | – | – | 2 | 5.1 | 3 | 6.8 | 1 | 3.3 | 6 | 5.2 |

| A. actinomycetemcomitans + P. gingivalis + T. denticola | – | – | 1 | 2.6 | 1 | 2.3 | 1 | 3.3 | 3 | 2.6 |

| A. actinomycetemcomitans + T. forsythia + T. denticola | – | – | 2 | 5.1 | 1 | 2.3 | 1 | 3.3 | 4 | 3.4 |

| P. gingivalis + T. forsythia + T. denticola | – | – | 1 | 2.6 | 2 | 4.5 | 6 | 20.0 | 9 | 7.8 |

| A. actinomycetemcomitans + P. gingivalis + T. forsythia + T. denticola | – | – | – | – | 4 | 9.1 | 2 | 6.7 | 6 | 5.2 |

| TOTAL | 3 | 100.0 | 39 | 100.0 | 44 | 100.0 | 30 | 100.0 | 116 | 100.0 |

In the analysis of the relationship between periodontal pathogens, there were significant associations for A. actinomycetemcomitans + P. gingivalis and A. actinomycetemcomitans + T. forsythia (p < 0.05), with odds ratios of 2.95 and 2.31, respectively. The percentage of sites with T.

forsythia + T. denticola was higher when P. gingivalis was present than when absent (66.7% vs. 19.4% and 42.6% vs. 25.8%, respectively); however, only the only significant association was for T. forsythia + P. gingivalis (p < 0.05), with an odds ratio 8.33. There was also a significant association for T. forsythia + T. denticola (p < 0.05), with an odds ratio of 2.54 (Table 5).

Table 5.

Associations between pathogens analyzed.

| P. gingivalis | T. forsythia | T. denticola | A. actinomycetemcomitans | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR‡ (95% CI§) | p-value(†) | OR‡ (95% CI§) | p-value(†) | OR‡ (95% CI§) | p-value(†) | OR‡ (95% CI§) | p-value(†) | |

| • P. gingivalis | – | – | 8.33 (3.57–19.43) | < 0.001* | 2.13 (0.97–4.67) | 0.056 | 2.95 (1.26–6.91) | 0.011* |

| • T. forsythia | – | – | 2.54 (1.15–5.59) | 0.019* | 2.31 (1.01–5.30) | 0.045* | ||

| • T. denticola | – | – | 1.84 (0.79–4.25) | 0.154 | ||||

| • A. actinomycetemcomitans | – | – | ||||||

significant difference at 5.0%

chi-square test

OR – odds ratio

CI – confidence interval

DISCUSSION

The present study assessed the occurrence of periodontal pathogens in a convenience sample of adult Brazilian nonsmokers with chronic periodontitis in the city of Recife (northeastern Brazil). It takes on particular importance in light of the small number of studies carried out on Brazilian populations, particularly those in the northeastern region of the country.

Strict inclusion and exclusion criteria were employed in the present study in order to obtain a homogeneous sample. Previous other studies evaluating the subgingival microbiota involved a considerable diversity of participants (8, 24, 25). Diversity in samples leads to a greater number of biases, but encourages the participation of a large number of individuals. Factors such as the inclusion of both smokers and nonsmokers with no distinguishing between the two, patients in use of antibiotics and anti-inflammatory agents, those with systemic diseases and those with tooth loss are examples of selection biases, as these aspects can influence the status of the subgingival microbiota and, consequently, affect the results. The eligibility criteria employed in the present study led to a small number of patients, but with similar characteristics.

The pathogens investigated are known to be associated with the progression and severity of periodontal disease. Epidemiological studies involving adults have demonstrated significant variation in the prevalence of periodontal pathogens depending on race, ethnicity, geographic location (24) and methodology employed.

In Brazil, few studies have been conducted to investigate the periodontal microbiota and most of these have been carried out in the state of São Paulo (southeastern Brazil) (7, 8, 13, 14, 15, 26). Comparing the data to those of reported in other studies involving Brazilian patients with periodontal disease, the frequency of pathogens was lower in the present study (7, 8, 9, 13, 15, 26). However, differences in methodology and distinct population characteristics (ethnic diversity) in the different regions investigated should be stressed.

Differences in the results reported in previous studies carried out in Brazil and elsewhere may also be explained by the different periodontal conditions assessed. The low presence of bacteria in the sites evaluated may be explained by the evaluation of a high number of shallow sites, as the patients in the present study exhibited different degrees of chronic periodontitis. A. actinomycetemcomitans

In sites with a probing depth ≥ 8 mm, a higher frequency T. forsythia + P. gingivalis and P. gingivalis + T. denticola + T. forsythia combinations was found, confirming the strong association between chronic periodontitis and red complex species, as also demonstrated by Socransky et al. (22) and Hamlet et al. (11). This fact can be explained by the deeper pockets offer a better medium for anaerobes and, consequently, greater colonization of these pathogens (11, 22). In addition, Zambon (28) also explains the strong association of T. forsythia and P. gingivalis pathogens in the pathogenesis of periodontitis, as these bacteria causes tissue loss and severe alveolar bone resorption. Considering these facts, it is expected that these pathogens be more present in deeper sites with greater signs of periodontal disease. Moreover, the simultaneous presence of these bacteria in deep sites suggests a symbiotic relationship between these virulent species, favoring, in this way, a further progression of periodontal disease.

As found in the study carried out by Hamlet et al. (11), the bacterium A. actinomycetemcomitans exhibited a different behavior from the other pathogens, with a lower frequency at deeper probing depths. This may be explained by the fact that this pathogen is a facultative anaerobe.

It was concluded that the bacteria P. gingivalis, T. forsythia and T. denticola are related to chronic periodontitis, presenting a higher occurrence in deep periodontal pockets. Moreover, the simultaneous presence of these bacteria in deep sites suggests a symbiotic relationship between these virulent species, favoring, in this way, a further progression of periodontal disease.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ainamo J., Bay I. Problems and proposals for recording gingivitis and plaque. Int. Dent. J. 1975;25:229–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Academy of Periodontology Consensus report on periodontal disease: pathogenesis and microbial factors. Ann. Periodontol. 1996;67:926–932. doi: 10.1902/annals.1996.1.1.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Academy of Periodontology International workshop for classification of periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann. Periodontol. 1999;4:7–112. doi: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Academy of Periodontology Parameter on chronic periodontitis with slight to moderate loss of periodontal support. J. Periodontol. 2000;71:853–855. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.5-S.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ashimoto A., Chen C., Bakker I., Slots J. Polymerase chain reaction detection of 8 putative periodontal pathogens in subgingival plaque of gingivitis and advanced periodontal lesions. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 1996;11:266–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1996.tb00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atieh A. Accuracy of real-time polymerase chain reaction versus anaerobic culture in detection of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis: a meta-analysis. J. Periodontol. 2008;79:1620–1629. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ávila-Campos M.J., Velásquez-Meléndez G. Prevalence of putative periodontopathogens from periodontal pacients and healthy subjects in São Paulo, SP, Brazil. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo. 2002;44:1–5. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652002000100001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ávila-Campos M.J. PCR detection of four periodontopathogens from subgingival clinical samples. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2003;34:81–84. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cortelli J.R., Cortelli S.C., Jordan S., Haraszthy V.I., Zambon J.J. Prevalence of periodontal pathogens in Brazilians with aggressive or chronic periodontitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2005;32:860–866. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dogan B., Antinhelmo J., Cetiner D., Bodur A., Emingil G., Buduneli E., Uygur C., Firatli E., Lakio L., Asikainen S. Subgingival microflora in Turkish patients with periodontitis. J. Periodontol. 2003;74:803–814. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.6.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamlet S.M., Cullinan M.P., Westerman B., Lindeman M., Bird P.S., Palmer J., Seymour G.J. Distribution of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonas gingivalis and Prevotella intermedia in an Australian population. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2001;28:1163–1171. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.281212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herrera D., Contreras A., Gamonal J., Oteo A., Jaramillo A., Silva N., Sanz M., Botero J.E, León R. Subgingival microbial profiles in chronic periodontitis patients from Chile, Colombia and Spain. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2007;35:106–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imbronito A.V., Okuda O.S., Freitas N.M., Lotufo R.F.M., Nunes F.D. Detection of herpes viruses and periodontal pathogens in subgingival plaque of patients with chronic periodontitis, generalized aggressive periodontitis, or gingivitis. J. Periodontol. 2008;79:2313–2321. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kantorski K.Z., Rodrigues A.S., Zimmemann G.S., Lotufo R.F.M. Ocurrence of Porphyromonas gingivalis in patients with periodontitis in Brazil. Ciênc. Odontol. Bras. 2006;9:26–31. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klein M.I., Gonçalves R.B. Detection of Tannerella forsythensis (Bacteroides forsythus) and Porphyromonas gingivalis by polimerase chain reaction in subjects with different periodontal status. J. Periodontol. 2003;74:798–802. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.6.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim T.S., Kang N.W., Lee S.B., Eickholz P., Pretzl B., Kim C.K. Differences in subgingival microflora of Korean and German periodontal patients. Arch. Oral Biol. 2009;54:223–229. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayanagi G., Sato T., Shimauchi H., Takahashi N. Detection frequency of periodontitis-associated bacteria by polymerase chain reaction in subgingival and supragingival plaque of periodontitis and healthy subjects. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 2004;19:379–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.2004.00172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mineoka T., Awano S., Rikimaru T., Kurata H., Yoshida A., Ansai T., Takehara T. Site-specific development of periodontal disease is associated with increased levels of Porphyromonas gingivalis, Treponema denticola, and Tannerella forsythia in subgingival plaque. J. Periodontol. 2008;79:670–676. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morikawa M., Chiba T., Tomil N., Sato S., Takahashi Y., Konishi K., Numabe Y., Iwata K., Imai K. Comparative analysis of putatite periodontopathic bacteria by multiplex polymerase chain reaction. J. Periodont. Res. 2008;43:268–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2007.01025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Offenbacher S. Periodontal diseases: pathogenesis. Ann. Periodontol. 1996;1:821–878. doi: 10.1902/annals.1996.1.1.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sakamoto M., Takeuchi Y., Umeda M., Ishikawa I., Benno Y. Rapid detection and quantification of five periodontopathic bacteria by real-time PCR. Microbiol. Immunol. 2001;45:39–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2001.tb01272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Socransky S.S., Haffajee A.D., Cugni M.A., Smith C., Kent Jr. R.L. Microbial complexes in subgingival plaque. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1998;25:134–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1998.tb02419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tatakis D.N., Kumar P.S. Etiology and pathogenesis of periodontal diseases. Dent. Clin. North Am. 2005;49:491–516. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Torrungruang K., Bandhaya P., Likittanasombat K., Grittayaphong C. Relationship between the presence of certain bacterial pathogens and periodontal status of urban Thai adults. J. Periodontol. 2009;80:122–129. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.080248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Winkelhoff A.J., Loos B.G., van der Reijden W.A., van der Velden U. Porphyromonas gingivalis, Bacteroides forsythus and other putative periodontal pathogens in subjects with and without periodontal destruction. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2002;29:1023–1028. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.291107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Victor L.V., Cortelli S.H., Aquino D.R., Carvalho Filho J., Cortelli J.R. Periodontal profile and presence of periodontal pathogens in young African-Americans from Salvador, BA, Brazil. Braz. J.Microbiol. 2008;39:226–232. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822008000200005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wara-aswapati N., Pitiphat W., Chanchaimongkon L., Taweechaisupapong S., Boch J.A., Ishikawa I. Red bacterial complex is associated with the severity of chronic periodontitis in a Thai population. Oral diseases. 2009;15:354–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2009.01562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zambon J.J. Periodontal disease: Microbial factors. Ann. Periodontol. 1996;1:879–925. doi: 10.1902/annals.1996.1.1.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]