Abstract

Kinetics of a lipase isolated from Bacillus sp. was studied. The enzyme showed maximum activity at pH 9 and temperature 60°C. The Michaelis constant (KM 0.31 mM) obtained from three different plots i.e., Lineweaver-Burk, Hanes-Wolf and Hofstee, was found to be lower than already reported lipases that confirmed higher affinity of the enzyme for its substrate p-NPL (p-nitrophenyl laurate). Vmax of the enzyme was found to be 7.6 µM/mL/min. Energy of activation calculated from Arrhenius plot was found to be 20.607 kJmol−1. Activation enthalpy (ΔH*) had negative trend and the value for the hydrolysis of p-NPL by the enzyme at optimum temperature was −2.748 kJmol−1. Activation entropy (ΔS*) and free energy of activation (ΔG*) of the enzyme were found to be 1.468 Jmol−1K−1 and −3.237 kJmol−1, respectively at optimum temperature. Low value of Q10 (0.04788) shows high catalytic activity of the enzyme. Mn2+, Fe2+ and Mg2+ enhanced the lipase activity whereas Cu2+, Na+ and Co2+ inhibited the enzyme activity. However, the enzyme activity was not affected significantly by K+ ions. EDTA and SDS also significantly inhibited the lipase activity. Activity of the enzyme was increased in n-hexane while decreased with increase in concentration of acetone, chloroform, ethanol and isopropanol.

Keywords: Bacillus sp., Kinetic study, Lipases, p-Nitrophenyl laurate, Tannery wastes, Organic solvents

INTRODUCTION

Lipases (triaclglycerol hydrolases, EC 3.1.1.3) are hydrolases acting on the carboxylic ester bonds present in acylglycerols to liberate fatty acids and glycerol. These are among the most important industrial enzymes in terms of their versatility (1, 2). Thermostable and alkalophilic lipases have great potential to be used in detergent, food flavoring, leather processing, pharmaceutical, cosmetics, etc (3). Lipases remain enzymatically active in organic solvents (4, 5) that enhances their potential and flexibility as biocatalysts against a wide range of unnatural hosts (6). These enzymes are the most widely used biocatalysts in organic chemistry (1), thus find tremendous applications in organic synthesis (7, 8). The regio- and/or enantioselectivity of lipases makes them highly attractive source to work precisely in various esterifications, alcoholysis, aminolysis or transformation reactions (9). The enzyme catalyzed reactions in organic solvents have advantages over the reactions carried out in aqueous medium due to many properties including “molecular memory” (10), therefore, lipase-catalyzed ester hydrolysis in water is converted into ester synthesis in non-aqueous media (1).

Alkalophilic microorganisms are widely distributed in nature and the alkalophilic Bacillus strains are often good sources of alkaline extracellular enzymes (11, 12). Microbial lipases are usually extracellular enzymes, which are produced by various fungi, actinomycetes and bacteria (13, 14). Lipases are of significant importance in leather industry. Degreasing of leather during its processing is an important use of lipases in tanning industry in the process of bating. Removal of fat and protein debris by chemical processes is both polluting and laborious (15). Lipases can play distinct role in resolving such problems of leather industry and tanneries. Therefore, researchers are always in search of novel lipases with high catalytic rates from microbial sources. We isolated a Bacillus sp. strain FH5 from tannery wastes that was found to be a good producer of lipases (16). Two lipases were purified (17), however only one with Mr 62 kDa was characterized and reported. In this paper we report kinetic and thermodynamic characteristics of the other lipase (24 kDa) produced from this strain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microorganism and enzyme production

Bacillus sp. FH5 isolated from tannery waste was grown in shake flask cultures in selective medium for the production of lipase (16). The lipases produced under optimum conditions were purified by acetone precipitation followed by chromatographic procedures i.e. gel filtration on Sephadex G-75 followed by ion-exchange chromatography on DEAE-cellulose (17). The lipase with Mr 24 kDa was subjected to further characterization.

Lipase Assay

The method of (18) was used for the determination of lipase activity. To 20 μL of lipase solution was added 880 μL buffer (0.1 M KH2PO4; 0.1% gum Arabic, 0.2% deoxycholate, pH 8.0). After three minutes of incubation at 37°C, 100 μL of 8 mM substrate (p-nitrophenyl laurate; pNPL) solubilized in isopropanol was added and re-incubated for 5 minutes at room temperature. The reaction was stopped by adding 0.5 mL of 3 M HCl and centrifuged at 10000xg for 10 minutes at room temperature. The 333 μL supernatant was mixed with 1 mL of 2 M NaOH and absorbance was recorded at 420 nm. One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that released 1 μmol of p-nitrophenol from pNPL in one minute.

Effect of temperature on lipase activity

The enzyme assay was performed as discussed above except that incubation was done at temperatures from 10–70°C in increments of 10°C.

Effect of pH

Optimum pH for lipase activity was determined covering the range (4-11) using buffers of different pH. The buffers were: pH 4 -6 (acetate); pH 7 (phosphate); pH 8 (Tris-HCl) and pH 9-11 (Glycine-NaOH).

Effect of substrate concentration

Lipase was assayed in reaction buffer (pH 8) with different concentrations (0.113-1.2 mM) of pNPL (p-nitrophenyl laurate) as a substrate. The values of Vmax (maximum velocity) and Km (Michaelis constant) were calculated from Lineweaver-Burk, Hofstee and Hanes-Woof plots.

Activation energy and Thermodynamic parameters

Activation energy (Ea) was determined from Arrhenius plot (19). The values for the activation enthalpy (ΔH*), free energy of activation (ΔG*) and the activation entropy (ΔS*) were calculated according the following equations:

Increase in reaction rate per 10 K rise in temperature (Q10)

The value of activation every was also used to calculate the increase in reaction rate, Q10, for every 10 K increase in temperature i.e. from T1 toT2, according to the following formula:

Effect of metal ions and inhibitors

The effect of metal ions viz Na+, K+, Mg+2, Mn+2, Fe+2, Cu+2, Co+2 and potential inhibitors EDTA (Ethylenediamine teteracetic acid) and SDS (sodium dodecyl sulphate) was studied by incubation of the enzyme in the presence of 1 mM metal ions or the inhibitor following the method of (19). The enzyme activities were determined by normal assay procedure as discussed above.

Effect of organic solvents on lipase activity

The enzyme was assayed in the presence of different percentages (10-100%) of organic solvents viz acetone, chloroform, ethanol, n-hexane and isopropanol using the assay procedure under the standard conditions as discussed above.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Extracellular lipases were produced from a local isolate of Bacillus sp. and purified with the help of acetone precipitation and different chromatographic steps as reporter earlier (17). Two lipases with Mr 64 and 24 kDa were obtained, and the lipase with 64 kDa was characterized and discussed. The lipase with Mr 24 kDa was also characterized and discussed below.

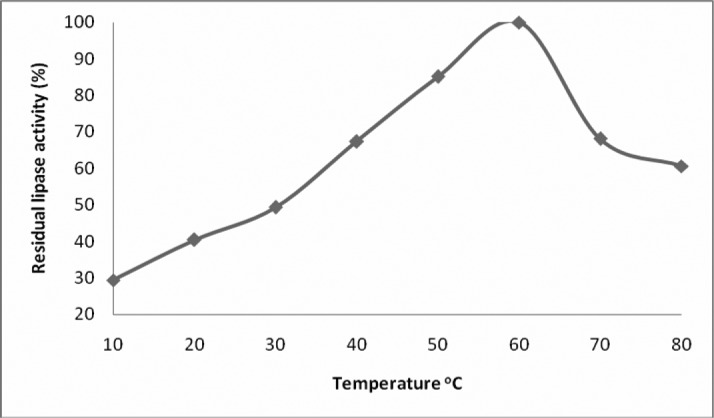

Effect of temperature on lipase activity

The temperature activity profile of Bacillus sp. lipase is shown in Figure 1. The lipase had an optimum temperature of 60°C that is comparable to the previously reported optimum temperatures for lipases from two different strains of Bacillus sp. (20-22). The lipase from Bacillus sp. reported by (22) lost 50% activity after incubation for 65 minutes at 70°C. A lipase from Bacillus coagulans BTS-3 showed maximum activity at 55°C and was found stable up to 70°C (23). Our lipase was found resistant at high temperature and exhibited 50% activity at 70°C and might be highly useful for industrial use. It was superior to that from Bacillus subtilis-168 having 35°C as its optimum temperature and losing all its activity at 55°C (18). The optimum temperature for a lipase from Bacillus subtilis IFFI 10210 (24) was also lower (45°C) as compared to our lipase.

Figure 1.

Effect of temperature on residual activity of the lipase isolated from Bacillus sp. Lipase assay was performed at pH 9 and at various temperatures. Each value represents mean from three independent experiments.

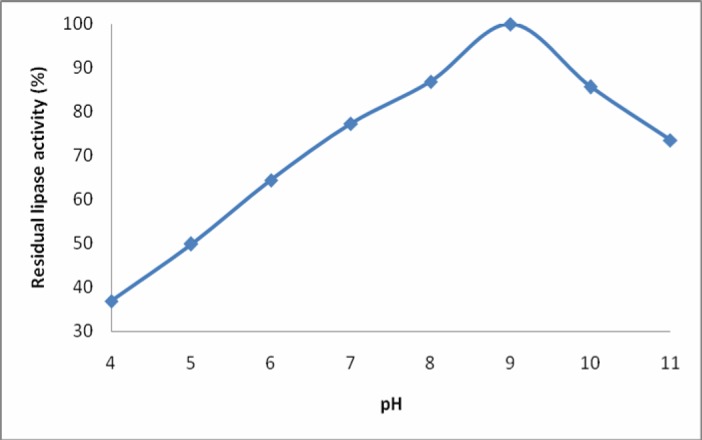

Effect of pH on lipase activity

The enzyme activity increased with an initial increase in pH and optimum activity was noted at pH 9 suggesting alkaline nature of the enzyme. Further increase in pH beyond optimum caused a rapid decrease in the enzyme activity (Figure 2). A pH optimum from 8-9 has previously been reported for lipases from some Bacillus species (22-25). However, lipase from Bacillus sp. is reported to (21) exhibit maximum activity at pH 5.6.

Figure 2.

Effect of pH on residual activity of the lipase isolated from Bacillus sp. Lipase assay was performed at 60°C and at various pH values. Each value represents mean from three independent experiments.

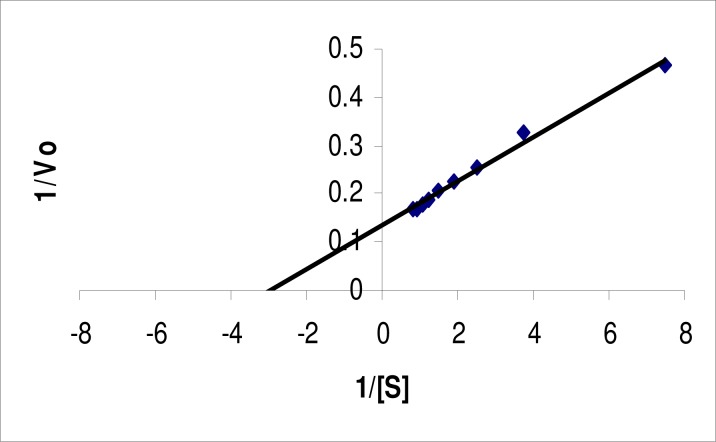

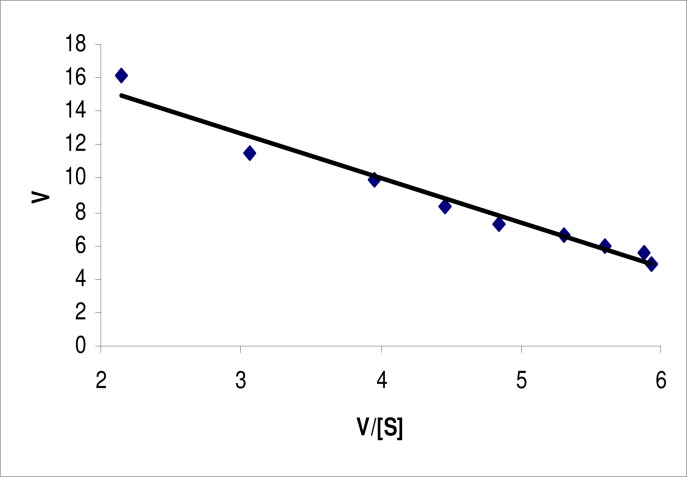

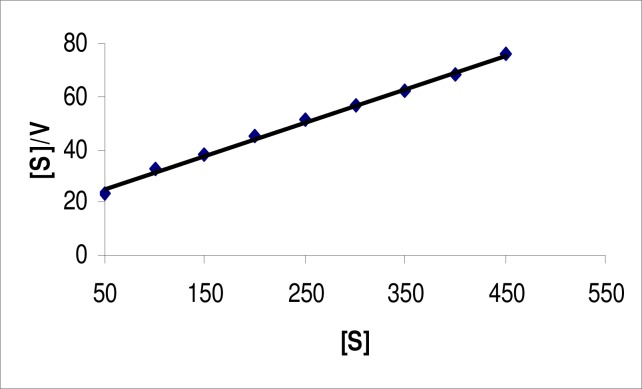

Effect of substrate concentration

The KM and Vmax for the lipase were determined using pNPL as a substrate. The KM value for the free enzyme, estimated from Lineweaver-Burk plot (Figure 3), Woolf-Augustinsson-Hofstee plot (Figure 4) and Hanes-Woolf plot (Figure 5) were 0.345, 0.361 and 0.399 mM, respectively with pNPL as substrate. The Vmax values obtained from the three plots were 7.61, 7.64 and 7.7 μM/mL/min., respectively. The KM and Vmax for a 64 kDa lipase from the same strain were found to be 5.05 mM and 0.416 μM/mL/min., respectively. The KM and Vmax for a lipase from Bacillus sp. J33 were found to be 2.5 mM and 0.4 μM/mL/min., respectively, with pNPL as substrate (26). Similarly, a lipase from another Bacillus sp. had KM and VMax 3.63 mM and 0.26 μM/mL/min., respectively. Whereas, a lipase from another Bacillus sp. exhibited KM and VMax of 0.5 mM and 0.319 μM/mL/min. on the same substrate (22). Our lipase therefore, had better affinity for the substrate and better catalytic activity as compared to previously reported lipases.

Figure 3.

Lineweaver-Burk plot for lipase from Bacillus sp. Lipase assay was conducted at various substrate concentrations at pH 9.0 and temperature 60°C. The data were plotted according to Lineweaver-Burk. Each value is average of three independent experiments.

Figure 4.

Woolf-Augustinsson-Hofstee plot for lipase from Bacillus sp. Lipase assay was conducted at various substrate concentrations at pH 9.0 and temperature 60°C. The data were plotted according to Woolf-Augustinsson-Hofstee equation. Each value is average of three independent experiments.

Figure 5.

Hanes-Woolf plot for lipase from Bacillus sp. Lipase assay was conducted at various substrate concentrations at pH 9.0 and temperature 60°C. The data were plotted according to Hanes-Woolf equation. Each value is average of three independent experiments.

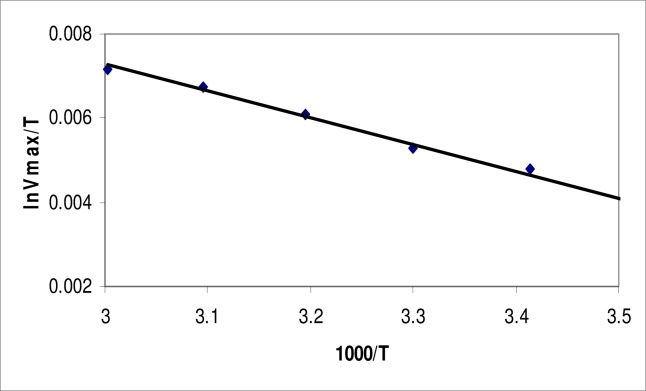

Activation energy and Thermodynamic parameters

Energy of Activation (Ea) for lipases of Bacillus sp. was 20.607 kJmol−1 calculated with the help of Arrhenius plot (Figure 6). It was observed that at 60°C the lipase had maximum catalysis in the conversion of pNPL into para-nitrophenol and lauric acid by using Activation energy (Ea) mentioned above. After this temperature, the enzyme started becoming denatured and showed less activity towards the conversion of the substrate into product. The small activation energy indicates a good relationship between enzyme and the substrate.

Figure 6.

Arrhenius plot for the determination of energy of activation of lipase produced from Bacillus sp.

Enthalpy of activation (ΔH*) was found to be negative and decreased with increase in incubation temperature (Table 1). This indicates alteration in the conformation of the enzyme (27). Negative value of ΔG* reflects that the enzyme reaction was spontaneously favorable in forward direction, and the maximum hydrolysis of the substrate was taking place under the conditions tested. Entropy (ΔS*) of the enzyme was found positive with slight decrease in the temperature range of 10 and 80°C. The positive values of ΔS* thermodynamically support the reaction. It further demonstrates an increase in disorderness that might be observed due to unfolding of the enzyme structure with increase in temperature.

Table 1.

Thermodynamic parameters of lipase isolated from Bacillus sp.

| Temp. (K) | ΔG* (kJmol−1) | ΔH* (kJmol−1) | ΔS* (Jmol−1K−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 283 | −2.751 | −2.332 | 1.479 |

| 293 | −2.848 | −2.415 | 1.476 |

| 303 | −2.945 | −2.499 | 1.474 |

| 313 | −3.042 | −2.582 | 1.472 |

| 323 | −3.140 | −2.665 | 1.470 |

| 333 | −3.237 | −2.748 | 1.468 |

Increase in reaction rate per 10°C rise in temperature (Q10)

Increase in reaction rate for energy 10°C convert to K rise in temperature was calculated for the lipase of Bacillus sp. The Q10 value obtained for the lipase was 0.04788. This value shows that there was on average, ~5% increase in the reaction rates of this enzyme when the temperature was increased from 20°C to 30°C convert to K. Lower Q10 values demonstrate high catalysis. A distinctive feature of enzyme catalysis is that the Q10 of a catalyzed reaction is lower as compared to the same reaction uncatalyzed.

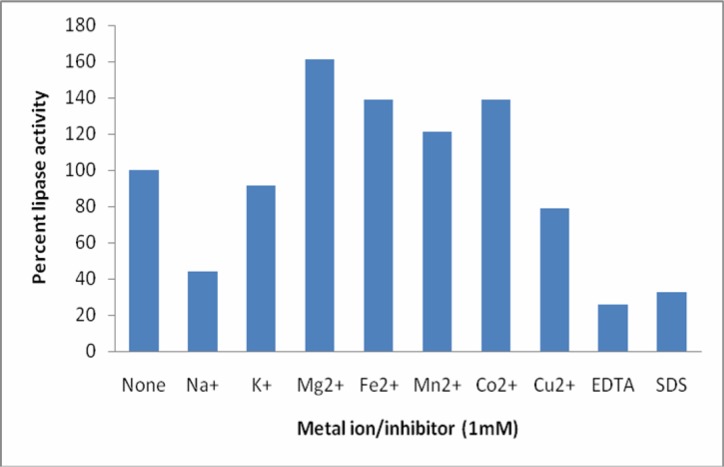

Effect of metal ions and inhibitors

The effect of metal ions viz Na+, K+, Mn+2, Fe+2, Mg2+, Cu+2, Co+2 and two potential inhibitors EDTA and SDS was studied on the lipase isolated from Bacillus sp. The results are summarized in Figure 7. Mn2+, Fe2+ and Mg2+ enhanced the lipase activity indicating that these ions do not compete with the enzyme whereas Cu2+, Na+ and Co2+ inhibited the enzyme activity showing competitive inhibition rendering enzyme to a reduced catalytic activity. K+, on the other hand, had no significant effect on the enzyme activity. Mg2+ has been reported to increase the lipase activity from Bacillus sp. (23, 24). However, in contrast to our findings, Mn2+ is reported to have inhibited activity of the lipase isolated from Bacillus sp. (18, 23). Sugihara and Tominaga (21) found that a lipase from Bacillus sp. was inhibited by the addition of Cu+2, whereas other metal ions including Mg+2 and Fe+2 had no effect on the enzyme activity. According to (24) Fe+2, Cu+2 and Co+2 inhibited the lipase activity from Bacillus subtilis. EDTA and SDS also strongly inhibited the lipolytic activity. The 64 kDa lipase reported earlier by our lab (17) was also inhibited by both of the inhibitors, although the inhibition was not as strong as for our lipase. SDS has been reported to completely inhibit the activity of the lipase isolated from Bacillus thermoleovorans ID-1 (28). However, contradictory reports have been reported for the effect of EDTA. In a few cases EDTA has stimulatory or no affect on lipase activity (29, 30), whereas in others it shows inhibitory effect (31). Strong inhibition of the lipase activity in our case shows that the enzyme requires metal ions that are chelated out with EDTA.

Figure 7.

Effect of metal ions and potential inhibitors on lipase activity. The metal ion or inhibitor was added at 1 mM concentration and the lipase activity was assayed under the standard conditions. The percent lipase activity for control was taken as 100%.

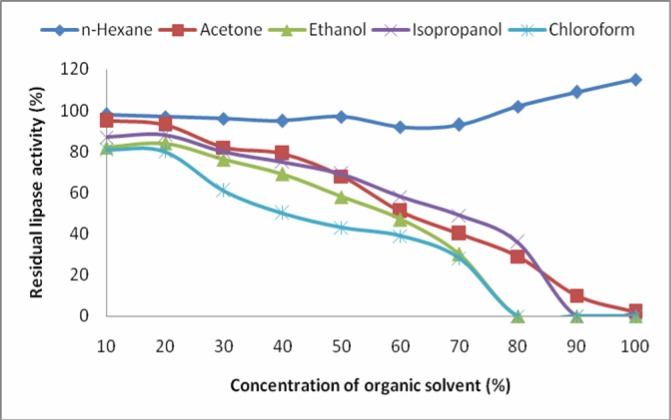

Effect of organic solvents on the enzyme activity

Utilization of enzymes, especially lipases, in organic solvents is gaining much industrial importance as the process leads to the development of products of high-added value (4, 32). We tested activity of the lipase in five different solvents i.e. acetone, chloroform, ethanol, n-hexane and isopropanol (Figure 8). The enzyme exhibited high activity in all the organic solvents except for chloroform. Maximum lipolytic residual activity was observed in n-hexane followed by isopropanol, acetone and ethanol. Except for n-hexane, the enzyme activity was decreased with increase in the solvent concentration. The lipolytic activity was enhanced at higher concentrations of n-hexane showing stimulatory effect of the solvent on the enzyme. Other solvents did not stimulate the lipolytic activity, however, high lipolytic activity was observed at lower concentrations of the organic solvents. Contradictory reports are found in literature regarding the effect of the organic solvents on lipase activity. A lipase from Bacillus sp. was stimulated in the presence of acetone while inhibited in n-hexane (21). On the other hand activity of the lipase from Bacillus sp. strain 42 was found to be enhanced in n-hexane (33). Lipase from Rhizopus oryzae was found stable for many days in different organic solvents, n-hexane being the most suitable (34).

Figure 8.

Effect of organic solvents on the activity of the lipase. The assay was carried out in the organic solvents at various concentrations under standard conditions.

Conclusively, 24 kDa lipase produced and isolated from the local isolate of Bacillus sp. exhibited favorable kinetics for its use in industrial and environmental applications.

Acknowledgments

One of the authors, M. I. Ghori, is grateful to Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan for the grant of a post-doctoral research fellowship in order to carry out this research work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jaeger K.E., Eggert T. Lipases for biotechnology. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2002;13:390–7. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(02)00341-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reetz M.T. Lipases as practical biocatalysts. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2002;6:145–50. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(02)00297-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hasan F., Shah A.A., Hameed A. Industrial applications of microbial lipases. Enzyme Microbial Technol. 2006a;39:235–251. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verma M.L., Azmi W., Kanwar S.S. Microbial lipases: at the interface of aqueous and non-aqueous media. A review. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2008;55:265–294. doi: 10.1556/AMicr.55.2008.3.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klibanov A.M., Zaks A. Enzymatic catalysis in organic media at 100°C. Science. 1984;224:1249–1251. doi: 10.1126/science.6729453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmid R.D., Verger R. Lipases: Interfacial enzymes with attractive applications. Angew Chem Int. 1998;37:1608–1633. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980703)37:12<1608::AID-ANIE1608>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Houde A., Kademi A., Leblanc D. Lipases and their industrial applications: an overview. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2004;118:155–170. doi: 10.1385/abab:118:1-3:155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bornscheuer U.T., Bessler C., Srinivas R., Krishna S.H. Optimizing lipases and related enzymes for efficient application. TRENDS in Biotechnol. 2002;20:433–437. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(02)02046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berglund P. Controlling lipase enantioselectivity for organic synthesis. Biomolecular Engineering. 2001;18:13–22. doi: 10.1016/s1389-0344(01)00081-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klibanov A.M. Improving enzymes by using them in organic solvents. Nature. 2001;409:241–246. doi: 10.1038/35051719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horikoshi K., Akiba T. Alkalophilic microorganism: a new microbial world. 1982. (Japan Scientific Societies Press Tokyo Japan)

- 12.Ito S., Kobayashi T., Ara K., et al. Alkaline detergent enzymes from alkaliphiles: enzymatic properties, genetics, and structures. Extremophiles. 1998;2:185–90. doi: 10.1007/s007920050059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hou C.T. Johnston Screening of lipase activities with cultures from the agricultural research service culture collection. J. Amer. Oil Chem. Soc. 1992;69:1088–1097. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta R., Gupta N., Rathi P. Bacterial lipases: an overview of production, purification and biochemical properties. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2004;64:763–81. doi: 10.1007/s00253-004-1568-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Posorske L.H. Industrial scale application of enzymes to the fat and oil industry. J. Amer. Oil Chem. Soc. 1984;61:1758–1760. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hasan F., Shah A.A., Hameed A. Influence of culture conditions on lipase production by Bacillus sp. FH5. Ann. Microbiol. 2006;56:247–252. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hasan F., Shah A.A., Hameed A. Purification and characterization of a mesophilic lipase from Bacillus subtilis FH5 stable at high temperature and pH. Acta Biol Hung. 2007;58:115–32. doi: 10.1556/ABiol.58.2007.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lesuisse E., Schanck K., Colson C. Purification and preliminary characterization of the extracellular lipase of Bacillus subtilis 168, an extremely basic pH-tolerant enzyme. Eur. J. Biochem. 1993;216:155–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siddiqui K.S., Azhar M.J., Rashid M.H., Rajoka M.I. Stability and identification of active-site residues of carboxymethylcellulases from Aspergillus niger and Cellulomonas biazotea. Folia Microbiol. (Praha). 1997;42:312–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02816941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee D., Koh Y., Kim K., et al. Isolation and characterization of a thermophilic lipase from bacillus thermoleovorans ID-1. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1999;179:393–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb08754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sugihara A., Tani T., Tominaga Y. Purification and characterization of a novel thermostable lipase from Bacillus sp. J. Biochem. (Tokyo). 1991;109:211–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nawani N., Khurana J., Kaur J. A thermostable lipolytic enzyme from a thermophilic Bacillus sp.: purification and characterization. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2006;290:17–22. doi: 10.1007/s11010-005-9076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar S., Kikon K., Upadhyay A., Kanwar S.S., Gupta R. Production, purification, and characterization of lipase from thermophilic and alkaliphilic Bacillus coagulans BTS-3. Protein Expr. Purif. 2005;41:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma J., Zhang Z., Wang B., et al. Overexpression and characterization of a lipase from Bacillus subtilis. Protein Expr. Purif. 2006;45:22–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lianghua T., Liming X. Purification and partial characterization of a lipase from Bacillus coagulans ZJU318. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2005;125:139–46. doi: 10.1385/abab:125:2:139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nawani N., Kaur J. Purification, characterization and thermostability of lipase from a thermophilic Bacillus sp. J33. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2000;206:91–6. doi: 10.1023/a:1007047328301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhatti H.N., Asgher M., Abbas A., Nawaz R., Sheikh M.A. Studies on kinetics and thermostability of a novel acid invertase from Fusarium solani. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006;54:4617–23. doi: 10.1021/jf053194g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee D.W., Koh Y.S., Kim K.J., et al. Isolation and characterization of a thermostable lipase from Bacillus thermoleovorans ID-1. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;179:393–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb08754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Handelsman T., Shoham Y. Producation and characterization of an extracellular thermostable lipase from a thermostable Bacillus sp. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 1994;40:435–443. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dharmsthiti S., Ammaranond P. Lipase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa LP602: biochemical properties and application for wastewater treatment. J Indus Microbiol Biotechnol. 1998;21:75–80. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Talon R., Dublet N., Montel M.C., Cantonnet M. Purification and characterization of extracellular Staphylococcus warneri lipase. Curr Microbiol. 1995;30:11–16. doi: 10.1007/BF00294517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gotor V. Lipases and (R)-oxynitrilases: useful tools in organic synthesis. J Biotechnol. 2002;96:35–42. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(02)00035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eltaweel M.A., Raja R.N.Z., Rahman A., Salleh A.B., Basri M. An organic solvent-stable lipase from Bacillus sp. strain 42. Ann. Microbiol. 2005;55:187–192. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Essamri M., Deyris V., Comeau L. Optimization of lipase production by Rhizopus oryzae and study on the stability of lipase activity in organic solvents. J Biotechnol. 1998;60:97–103. [Google Scholar]