Abstract

Halophiles are excellent sources of enzymes that are not only salt stable but also can withstand and carry out reactions efficiently under extreme conditions. The aim of the study was to isolate and study the diversity among halophilic bacteria producing enzymes of industrial value. Screening of halophiles from various saline habitats of India led to isolation of 108 halophilic bacteria producing industrially important hydrolases (amylases, lipases and proteases). Characterization of 21 potential isolates by morphological, biochemical and 16S rRNA gene analysis found them related to Marinobacter, Virgibacillus, Halobacillus, Geomicrobium, Chromohalobacter, Oceanobacillus, Bacillus, Halomonas and Staphylococcus genera. They belonged to moderately halophilic group of bacteria exhibiting salt requirement in the range of 3–20%. There is significant diversity among halophiles from saline habitats of India. Preliminary characterization of crude hydrolases established them to be active and stable under more than one extreme condition of high salt, pH, temperature and presence of organic solvents. It is concluded that these halophilic isolates are not only diverse in phylogeny but also in their enzyme characteristics. Their enzymes may be potentially useful for catalysis under harsh operational conditions encountered in industrial processes. The solvent stability among halophilic enzymes seems a generic novel feature making them potentially useful in non-aqueous enzymology.

Keywords: Halophiles, Biodiversity, Halophilic enzymes, Hydrolases, Solvent-stable.

INTRODUCTION

Screening of new source of novel and industrially useful enzymes is a key research pursuit in enzyme biotechnology. For applications in industrial processes, the enzymes should be stable at high temperature, pH, presence of salts, solvents, toxicants etc. In this context, the halophiles have emerged as a vast repository of novel enzymes in recent years. Enzymes derived from halophiles are endowed with unique structural features and catalytic power to sustain the metabolic and physiological processes under high salt conditions. Some of these enzymes have been reported to be active and stable under more than one extreme condition (14, 17, 30).

Halophiles have mainly been isolated from saltern crystallizer ponds, the Dead Sea, solar lakes and hypersaline lakes (24, 34). Culture dependent diversity studies on halophiles have been done from Tunisian Solar Saltern (4), Tuzkoy salt mine, Turkey (6), Howz Soltan Lake, Iran (28) and hypersaline environments in south Spain (29). In Indian context, the halophilic diversity has been limited to the marine salterns near Bhavnagar (9), Lonar Lake (16) and Peninsular coast (26). Enzymatic diversity among halophiles of Indian origin has hardly been profiled. A systematic study on diversity of halophiles from different saline habitats of India would be of great importance, especially comparison of biochemical, metabolic and enzymatic characteristics among them.

The present study focuses on the (i) isolation of moderate halophiles from various saline habitats of India viz. coastal regions of Gujarat, Goa, Kerala and Sambhar Salt Lake, Rajashthan (ii) screening for industrially important enzymes (especially amylases, lipases and proteases) and (iii) studying novel properties in these enzymes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of enzyme producing halophiles

Soil and water samples were collected from Sambhar Salt Lake (Rajasthan, 26°58′N75°05′E), sea coast of Kozhikode (Kerala, 11°25′N75°77′E), Goa (Goa, 15°59′N73°73′E), Nagoa (Diu, 20°71′N70°92′E), Somnath (Gujarat, 20°88′N70°40′E), Veraval (Gujarat, 20°91′N70°35′E) and Triveni Sangam (Gujarat, 20°71′N70°97′E).

Halophiles were isolated by salt (100.0/200.0 gL-1, NaCl) and substrate (starch/ olive oil/ gelatin) enrichment. The isolation media contained (gL-1): NaCl 100.0/200.0; Starch/ olive oil/ gelatin 10.0; MgSO4.7H2O 0.4; MgCl2.6H2O 0.7; CaCl2.2H2O 0.5; KH2PO4 0.3; K2HPO4 0.3; (NH4)2SO4 0.5; 0.01% of trace elements solution containing (gL-1) metal: B 0.26; Cu 0.5; Mn 0.5; Mo 0.06 and Zn 0.7 (27). Different dilutions of soil or water samples were added to the above medium and incubated at 30 ºC for 96h. The growth was diluted 10 times and plated on complete medium agar (gL-1): glucose 10.0; peptone 5.0; yeast extract 5.0; KH2PO4 5.0; agar 30.0; and NaCl 100.0. Resultant colonies were purified by repeated streaking on complete media agar. The isolates were stored at 4 ºC and sub-cultured at 15 days intervals.

Screening of hydrolase activities

Hydrolase producing bacteria among the isolates were screened by plate assay on starch, tributyrin and gelatin agar plates for amylase, lipase and protease respectively.

Amylolytic activity of the cultures was screened on starch nutrient agar plates containing gL-1: starch 10.0; peptone 5.0; yeast extract 3.0; agar 30.0; NaCl 100.0. The pH was from 7.0 to 10.0 depending on experimental conditions. After incubation at 30 ºC for 72h, the zone of clearance was determined by flooding the plates with iodine solution. The potential amylase producers were selected based on ratio of zone of clearance diameter to colony diameter.

Proteolytic activity of the isolates was similarly screened on gelatin nutrient agar plates containing 10.0 gL-1 of gelatin. The isolates showing zones of gelatin clearance upon treatment with acidic mercuric chloride were selected and designated as protease producing bacteria.

Lipase activity of the cultures was screened on tributyrin nutrient agar plates containing 1% (v/v) of tributyrin. Isolates that showed clear zones of tributyrin hydrolysis were identified as lipase producing bacteria.

Identification and characterization of potential halophilic isolates

For identification of strains by 16S rRNA gene sequencing, the genomic DNA was extracted by PrepManTM Ultra sample preparation kit (Applied Biosystems Inc, CA, USA). The 16S rRNA gene sequence was obtained by using MicroSeq® 16S rRNA gene sequencing kit containing universal primers (Applied Biosystems Inc., CA, USA). The identification of phylogenetic neighbours was initially carried out by the BLAST (1) and megaBLAST (35) programmes against the database of type strains with published prokaryotic names. The 50 sequences with the highest scores were then selected for the calculation of pairwise sequence similarity using global alignment algorithm, which was implemented at the EzTaxon server (www.eztaxon.org)(7). The phylogenetic tree was constructed using CLC genomics workbench 4.0.3 (CLC Bio, Denmark).

The biochemical characterization was carried out by HiBio-ID Test Kits.

Production of hydrolases

Hydrolase activities of the isolate exhibiting larger zone of clearance on plate were further confirmed by assaying enzymatic activity in broth. The isolates were seeded into the medium containing (gL-1): gelatin/starch/olive oil 10.0; peptone 5.0; yeast extract 5.0; NaCl 50.0–200.0 and pH 7.0. The incubation was carried out at 150 rpm and 30 °C for 96h. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000xg for 10 min at 4 °C and cell free supernatant was assayed for respective enzymatic activities.

Enzyme assay

Amylase was assayed following the method of Bernfeld (5) using starch as a substrate. One unit of amylase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme releasing 1 μmol of maltose equivalent per minute from soluble starch under assay conditions. Lipase activity was determined using p-nitrophenol palmitate (pNPP) as substrate following the method described by Kilcawley et al. (18). One unit of lipase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme liberating 1 nmol of pNP (p-nitrophenol) per minute under standard assay conditions. Protease activity was measured by using casein as a substrate following the method of Shimogaki et al. (31). One unit of protease activity is defined as the amount of enzyme liberating 1 µg of tyrosine per minute under assay conditions.

Characterization of enzymes

pH optimum was determined by assaying the enzyme at various pH ranging from 5.0 to 10.0 using 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0–5.5), 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0–7.5) and 0.1 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0–10.0).

The effect of salt on enzymatic activity was determined by varying salt concentrations (0–20% NaCl) in the assay mixture. For determining the temperature optima, assay was carried out at various temperatures (30–80 ºC). The thermal stability of enzymes was determined by preincubating at various temperatures (40–80 °C), and estimating the residual activity in aliquots withdrawn at various time intervals. Maximum temperature at which enzyme retained 100% activity for 1h was determined. Other conditions were kept same as per standard assay procedures.

Organic solvent stability

Three millilitres of enzyme was mixed with 1.0 mL of organic solvents in screw capped tubes. The mixture was incubated at 30 ºC with constant shaking at 200 rpm for 24h. Samples were withdrawn from aqueous phase and residual enzyme activity estimated. Enzyme incubated without solvent was treated as control.

All the experiments were done in triplicate and the variation was within ±5%.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Isolation of halophiles and screening of hydrolase producers

Halophiles have been perceived as a potential source of industrially useful enzymes endowed with exceptional stabilities. The present study was undertaken to screen stable enzymes from halophiles occurring in saline habitats of India. The site dependent diversity of halophiles from west coast, south coast and Salt Lake located in western part of India was investigated. A total of 108 halophilic isolates producing hydrolases were isolated by salt (NaCl) and substrate (starch/ olive oil/ gelatin) enrichment.

Distributions of hydrolytic activity among the isolates are summarized in Table 1. Seventy eight isolates secreted only one predominant enzyme, protease (33), lipase (23) and amylase (22) respectively. Nine isolates produced both lipase and protease, whereas one isolate showed all three activities. Based on ratio of zone of clearance diameter to colony diameter, twenty one isolates were selected for further study.

Table 1.

Sampling sites and distribution of hydrolases producing halophiles

| Sample site | Sample type | pH | Temperature (°C) | Grampositive isolates | Gramnegative isolates | Enzymes present | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amylase | Lipase | Protease | ||||||

| Kozhikode, Kerala | Sea water and sand | 7.6 | 31.2 | 3 | 9 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| Nagoa, Diu | Sea water and soil | 7.9 | 30.6 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 7 |

| Somnath, Gujarat | Sea water | 7.7 | 30.5 | 7 | 11 | 4 | 9 | 8 |

| Triveni Sangam, Gujarat | Sea water and soil | 7.8 | 31.5 | 9 | 12 | 7 | 5 | 11 |

| Veraval, Gujarat | Sea water | 7.7 | 30.3 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 5 |

| Goa | Sea water | 7.7 | 30.6 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| Sambhar Salt Lake, Rajasthan | Soil and water | 7.8 | 35 .0 | 11 | 9 | 7 | 4 | 11 |

Characterization of halophilic isolates

Among the selected isolates, sixteen were Gram-positive and five Gram-negative. The isolates generally grew in the salt range of 3–20% NaCl, with an optimum requirement of about 5% salt indicating them to be moderately halophilic according to the classification of Kushner (20). The isolates grew in alkaline pH range at average pH~ 7.5–8.0.

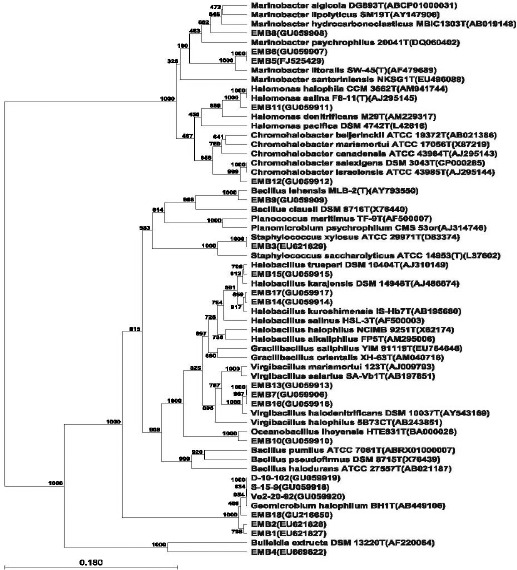

Identification by 16S rRNA gene analysis

The 16S rRNA gene analysis related their grouping in nine major genus; Marinobacter, Virgibacillus, Halobacillus, Geomicrobium, Chromohalobacter, Oceanobacillus, Bacillus, Halomonas and Staphylococcus. Gram-negative isolates of Marinobacter, Chromohalobacter and Halomonas genus belonged to Gamma-Proteobacteria and Gram-positive isolates of Virgibacillus, Halobacillus, Geomicrobium, Oceanobacillus and Bacillus belonged to Firmicutes.

The GenBank accession numbers of the isolates along with their closest phylogenetic neighbour are presented in Table 2. Geomicrobium was the most common genus, six halophilic isolates affiliated to this genus showed similarity to Geomicrobium halophilum. The genus Marinobacter was found only from the Kozhikode. Virgibacillus was represented from Kozhikode, Triveni Sangam and Nagoa. The phylogenetic association of the isolates is shown in Figure 1. All the nine genus obtained in present study, are commonly occurring in various saline habitats across the globe. Presence of Marinobacter, type isolate Marinobacter hydrocarbonoclasticus has been reported from Meditteranean sea (13). Halobacillus litoralis (33), Oceanobacillus iheyensis (21) and Geomicrobium halophilum (10) have been isolated from Great Salt Lake, Iheya ridge and soil samples from Japan respectively.

Table 2.

16S rRNA gene identification of halophilic bacterial isolates producing potent hydrolases

| Sample Site | Isolate | GenBank Accession number | Closest phylogenetic neighbour | Similarity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sambhar Lake | Haloalkaliphilic bacterium EMB1 | EU621827 | Geomicrobium halophilum | 99.458 |

| Haloalkaliphilic bacterium EMB2 | EU621828 | Geomicrobium halophilum | 99.457 | |

| Haloalkaliphilic bacterium EMB3 | EU621829 | Staphylococcus xylosus | 100 | |

| Haloalkaliphilic bacterium EMB4 | EU669822 | Bulleidia extructa | 88.996 | |

| Kozhikode | Marinobactersp. EMB5 | FJ525429 | Marinobacter litoralis | 99.864 |

| Marinobactersp. EMB6 | GU059907 | Marinobacter litoralis | 99.863 | |

| Virgibacillussp. EMB7 | GU059906 | Virgibacillus halodenitrificans | 99.414 | |

| Marinobactersp. EMB8 | GU059908 | Marinobacter santoriniensis | 96.288 | |

| Goa | Bacillussp. EMB9 | GU059909 | Bacillus lehensis | 99.395 |

| Oceanobacillussp. EMB10 | GU059910 | Oceanobacillus iheyensis | 99.607 | |

| Triveni Sangam | Chromohalobactersp. EMB12 | GU059912 | Chromohalobacter israelensis | 100 |

| Virgibacillussp. EMB13 | GU059913 | Virgibacillus halodenitrificans | 99.23 | |

| Halobacillussp. EMB14 | GU059914 | Halobacillus kuroshimensis | 99.609 | |

| Nagoa | Halobacillussp. EMB15 | GU059915 | Halobacillus trueperi | 99.414 |

| Virgibacillussp. EMB16 | GU059916 | Virgibacillus halodenitrificans | 99.219 | |

| Halobacillussp. EMB17 | GU059917 | Halobacillus kuroshimensis | 99.608 | |

| Haloalkaliphilic bacterium D-10-102 | GU059919 | Geomicrobium halophilum | 100 | |

| Somnath | Halomonassp. EMB11 | GU059911 | Halomonas salina | 99.795 |

| Haloalkaliphilic bacterium EMB18 | GU216650 | Geomicrobium halophilum | 99.796 | |

| Haloalkaliphilic bacterium S-15-9 | GU059918 | Geomicrobium halophilum | 100 | |

| Veraval | Haloalkaliphilic bacterium Ve2-20-92 | GU059920 | Geomicrobium halophilum | 100 |

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic inference based on 16S rRNA gene analysis of halophilic isolates. Each organism is preceded by its NCBI accession number. Bootstrap values and horizontal scale bar representing number of substitutions per nucleotide are indicated.

Screening and preliminary characterization of the halophilic enzymes

Since the basic objective of study was to screen novel/ stable enzymes among halophiles, the isolates were grown in culture media to obtain crude enzyme for further characterization. Amylase, lipase and protease were chosen for the study, considering their high industrial usage. Maximum amylase was produced by Marinobacter sp. EMB8. Lipase and protease production level were maximum in Marinobacter sp. EMB5 and Bacillus sp. EMB9 respectively.

Crude enzymes were partially characterized to investigate their properties and stability (Table 3). Their optimum salt requirement in most cases was in the range of 1–2%. These were optimally active at pH 9.0 or above, in general. Their temperature optimum ranged between 50–65 °C. Interestingly, all the hydrolases were stable in organic solvents. Based on these results, hydrolases from moderate halophiles can be categorized to be alkaline in nature, moderate in salt requirement and endowed with solvent stability, a common novel feature among all.

Table 3.

Preliminary characterization of halophilic enzymes

| Sample Site | Microorganism | Potent enzyme produced | Production level (UmL-1) | pH optima | Salt optima (%, NaCl) | Temp. optima (°C) | Solvent-stability† (25%, v/v) | Thermal stability (°C) # |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sambhar Lake | Haloalkaliphilic bacterium EMB1 | Protease | 28 | 9.5 | 5 | 50 | Stable | 50 |

| Haloalkaliphilic bacterium EMB2 | Protease | 37 | 10.0 | 3 | 50 | Stable | 50 | |

| Haloalkaliphilic bacterium EMB3 | Protease | 21 | 9.0 | 6 | 45 | Stable | 50 | |

| Haloalkaliphilic bacterium EMB4 | Amylase | 1.2 | 9.0 | 3 | 40 | Stable | 50 | |

| Kozhikode | Marinobactersp. EMB5 | Lipase | 129 | 9.0 | 2 | 50 | Stable | 60 |

| Marinobactersp. EMB6 | Lipase | 88 | 9.5 | 2 | 65 | Stable | 60 | |

| Virgibacillussp. EMB7 | Protease | 156 | 7.5 | 1 | 60 | Stable | 50 | |

| Marinobactersp. EMB8 | Amylase | 4 | 7.0 | 1 | 45 | Stable | 50 | |

| Goa | Bacillussp. EMB9 | Protease | 191 | 9.0 | 1 | 60 | * | * |

| Oceanobacillussp. EMB10 | Protease | 26 | 9.0 | 1 | 55 | * | * | |

| Triveni Sangam | Chromohalobactersp. EMB12 | Lipase | 65 | 9.5 | 2 | 65 | Stable | 50 |

| Virgibacillussp. EMB13 | Protease | 62 | 7.5 | 1 | 60 | Stable | 50 | |

| Halobacillussp. EMB14 | Amylase | 0.3 | 7.5 | 1 | 55 | * | * | |

| Nagoa | Halobacillussp. EMB15 | Amylase | 0.2 | 8.0 | 1 | 55 | * | * |

| Virgibacillussp. EMB16 | Protease | 60 | 7.5 | 1 | 60 | * | * | |

| Halobacillussp. EMB17 | Amylase | 0.2 | 7.5 | 1 | 55 | * | * | |

| Haloalkaliphilic bacterium D-10-102 | Lipase | 7 | 9.5 | 1.5 | 65 | * | * | |

| Somnath | Halomonassp. EMB11 | Lipase | 42 | 9.0 | 2 | 65 | * | * |

| Haloalkaliphilic bacterium EMB18 | Protease | 38 | 10.0 | 2 | 55 | Stable | 55 | |

| Haloalkaliphilic bacterium S-15-9 | Lipase | 57 | 9.5 | 1.5 | 65 | Stable | 60 | |

| Veraval | Haloalkaliphilic bacterium Ve2-20-92 | Lipase | 15 | 9.5 | 1.5 | 65 | * | * |

Not defined

Solvent stability checked in hexane, cyclohexane, decane, dodecane and toluene

Stability for 1h

Prominent amylase, lipase and protease producers have been reported from Salinivibrio, Halomonas and Salinivibrio genus respectively from different hypersaline environment of south Spain (29). Study from Howz Soltan Lake, Iran showed majority of amylase producers were Oceanobacillus and Halobacillus. Gracibacillus and Halomonas produced lipase and Virgibacillus produced protease (28). The hydrolase producing ability was also observed in moderately halophilic bacteria from Marinobacter, Chromohalobacter and Halomonas genera from the Tunisian Solar Saltern (4).

In the present work, amylase from Marinobacter sp. EMB8, Halobacillus sp. EMB14, EMB15 and EMB17 and Haloalkaliphilic bacterium EMB4 have shown noticeable production level (up to 4.0 UmL-1). Among halophiles amylase production has been previously reported from Halomonas meridiana (8) and Chromohalobacter sp. TVSP 101 (25). Amoozegar et al. (2) have characterized Halobacillus sp. MA-2 amylase, which exhibited pH optima at 7.5–8.5 and temperature optima at 50 ºC. As compared to this, all three isolates of Halobacillus sp. although have pH optima in 7.5–8.0 range and temperature optimum in the range 55–60 ºC. Amylase from a Marinobacter genus is being reported for the first time to best of our knowledge.

Marinobacter sp. EMB5, Marinobacter sp. EMB6, Halomonas sp. EMB11, Chromohalobacter sp. EMB12 and four Geomicrobium sp. isolate were found to be potent lipase producers (up to 129.0 UmL-1). Marinobacter lipolyticus (22) and Chromohalobacter sp. (29) have been previously described for lipase production. The lipase from Geomicrobium sp. is being reported for the first time to best of our knowledge. Till date very few halophilic lipases have been characterized, these are from Salicola sp. IC10 (23) and Salinivibrio sp. strain SA-2 (3). Solvent stability has not been reported in any these cases, which is highlight of Geomicrobium sp. lipase characteristics in present study.

Three isolates belonging to Virgibacillus sp., Geomicrobium sp. and one each Oceanobacillus and Bacillus sp. were potent protease producers (up to 191 UmL-1). All the Virgibacillus sp. isolates were only protease producers irrespective of site of their isolation. Virgibacillus sp. SK33 protease has been reported to be salt tolerant and stable in organic solvents (32).

Solvent stability a generic novel feature in halophiles

Solvent stability as a generic feature marks these novel enzymes for further study. Solvent stability has been observed as a novel trait among the halophilic enzymes in recent years (15). Solvent stability in halophilic enzymes may be attributed to the fact that they work in low water activity caused by high salt surroundings. Such enzymes are potentially useful in synthesis applications (12). Halophilic hydrolases investigated in present study were stable in 25% (v/v) concentration of hexane, cyclohexane, decane, dodecane and toluene.

Amylase from Haloarcula sp. strain S-1 remained active and stable in presence of 66% benzene, toluene and chloroform (11). Solvent stable proteases have been reported from Halobacterium salinarum (19) and Geomicrobium sp. EMB2 (17).

All the 108 hydrolase producers isolated from diverse saline habitats of India belong to moderate halophiles category. Moderately halophilic bacteria constitute the most versatile group of microorganisms that could be used as a source of salt-adapted enzymes. These have advantage over extreme halophiles in that they do not have a strict salt requirement and grow in wide salt range. Solvent stability of amylase, lipase and protease from these halophilic isolates make them potentially useful for application in non-aqueous enzymology for synthesis of oligosaccharides, esters and peptides.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The financial support by the Department of Biotechnology (Government of India) is gratefully acknowledged. Author SK is grateful to the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), India, for Research Fellowship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S.F., Madden T.L., Schaeffer A.A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., Lipman D.J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amoozegar M.A., Malekzadeh F., Malik K.A. Production of amylase by newly isolated moderate halophile, Halobacillus sp. strain MA-2. J. Microbiol. Meth. 2003;52:353–359. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(02)00191-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amoozegar M.A., Salehghamari E., Khajeh K., Kabiri M., Naddaf S. Production of an extracellular thermohalophilic lipase from a moderately halophilic bacterium, Salinivibrio sp. strain SA-2. J. Basic Microbiol. 2008;48:160–167. doi: 10.1002/jobm.200700361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baati H., Amdouni R., Gharsallah N., Sghir A., Ammar E. Isolation and characterization of moderately halophilic bacteria from Tunisian solar saltern. Curr. Microbiol. 2010;60:157–161. doi: 10.1007/s00284-009-9516-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernfeld P. Amylase, α and β. Meth. Enzymol. 1955;1:149–158. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birbir M., Ogan A., Calli B., Mertoglu B. Enzyme characteristics of extremely halophilic archaeal community in Tuzkoy salt mine, Turkey. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2004;20:613–621. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chun J., Lee J.-H., Jung Y., Kim M., Kim S., Kim B.K., Lim Y.W. EzTaxon: a web-based tool for the identification of prokaryotes based on 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequences. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007;57:2259–2261. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64915-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coronado M., Vargas C., Hofemeister J., Ventosa A., Nieto J.J. Production and biochemical characterization of an α-amylase from the moderate halophile Halomonas meridiana. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2000;183:67–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb08935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dave S.R., Desai H.B. Microbial diversity at marine salterns near Bhavnagar, Gujarat, India. Curr. Sci. 2006;90:497–499. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Echigo A., Minegishi H., Mizuki T., Kamekura M., Usami R. Geomicrobium halophilum gen. nov., sp. nov., moderately halophilic and alkaliphilic bacteria isolated from soil samples. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2010;60:990–995. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.013268-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukushima T., Mizuki T., Echigo A., Inoue A., Usami R. Organic solvent tolerance of halophilic α-amylase from a Haloarchaeon, Haloarcula sp. strain S-1. Extremophiles. 2005;9:85–89. doi: 10.1007/s00792-004-0423-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaur R., Gupta A., Khare S.K. Purification and characterization of lipase from solvent tolerant Pseudomonas aeruginosa PseA. Process Biochem. 2008;43:1040–1046. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gauthier M.J., Christen B.R., Fernandez L., Acquaviva M., Bonin P., Bertrand J.-C. Marinobacter hydrocarbonoclasticus gen. nov,, sp. nov,, a new, extremely halotolerant, hydrocarbon-degrading marine bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1992;42:568–576. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-4-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gomes J., Steiner W. The biocatalytic potential of extremophiles and extremozymes. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2004;42:223–235. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta A., Khare S.K. Enzymes from solvent-tolerant microbes: Useful biocatalysts for non-aqueous enzymology. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2009;29:44–54. doi: 10.1080/07388550802688797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joshi A.A., Kanekar P.P., Kelkar A.S., Shouche Y.S., Wani A.A., Borgave S.B., Sarnaik S.S. Cultivable bacterial diversity of alkaline Lonar Lake, India. Microb. Ecol. 2008;55:163–172. doi: 10.1007/s00248-007-9264-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karan R., Khare S.K. Purification and characterization of a solvent stable protease from Geomicrobium sp. EMB2. Environ. Technol. 2010;31:1061–1072. doi: 10.1080/09593331003674556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kilcawley K.N., Wilkinson M.G., Fox P.F. Determination of key enzyme activities in commercial peptidase and lipase preparations from microbial or animal sources. Enzym. Microb. Tech. 2002;31:310–320. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim J., Dordick J.S. Unusual salt and solvent dependence of a protease from an extreme halophile. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1997;55:471–479. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19970805)55:3<471::AID-BIT2>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kushner D.J. The Halobacteriaceae. In: Woese C.R., Wolfe R.S., editors. The Bacteria. Vol. 8. London: Academic Press; 1985. pp. 171–214. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu J., Nogi Y., Takami H. Oceanobacillus iheyensis gen. nov., sp. nov., a deep-sea extremely halotolerant and alkaliphilic species isolated from a depth of 1050m on the Iheya Ridge. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2001;205:291–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martín S., Márquez M.C., Sánchez-Porro C., Mellado E., Arahal D.R., Ventosa A. Marinobacter lipolyticus sp. nov., a novel moderate halophile with lipolytic activity. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2003;53:1383–1387. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02528-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moreno M.L., Garcia M.T., Ventosa A., Mellado E. Characterization of Salicola sp. IC10, a lipase- and protease-producing extreme halophile. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2009;68:59–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2009.00651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oren A. Molecular ecology of extremely halophilic Archaea and Bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2002;39:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2002.tb00900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prakash B., Vidyasagar M., Madhukumar M.S., Muralikrishna G., Sreeramulu K. Production, purification, and characterization of two extremely halotolerant, thermostable, and alkali-stable α-amylases from Chromohalobacter sp. TVSP 101. Process Biochem. 2009;44:210–215. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raghavan T.M., Furtado I. Occurrence of extremely halophilic Archaea in sediments from the continental shelf of west coast of India. Curr. Sci. 2004;86:1065–1067. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rahman R.N.Z.R.A., Leow T.C., Salleh A.B., Basri M. Geobacillus zalihae sp. nov., a thermophilic lipolytic bacterium isolated from palm oil mill effluent in Malaysia. BMC Microbiol. 2007;7:77–86. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-7-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rohban R., Amoozegar M.A., Ventosa A. Screening and isolation of halophilic bacteria producing extracellular hydrolases from Howz Soltan Lake, Iran. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009;36:333–340. doi: 10.1007/s10295-008-0500-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sánchez-Porro C., Martín S., Mellado E., Ventosa A. Diversity of moderately halophilic bacteria producing extracellular hydrolytic enzymes. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2003;94:295–300. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2003.01834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sellek G.A., Chaudhuri J.B. Biocatalysis in organic media using enzymes from extremophiles. Enzym. Microb. Tech. 1999;25:471–482. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shimogaki H., Takeuchi K., Nishino T., Ohdera M., Kudo T., Ohba K., Iwama M., Irie M. Purification and properties of a novel surface active agent and alkaline-resistant protease from Bacillus sp. Y. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1991;55:2251–2258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sinsuwan S., Rodtong S., Yongsawatdigul J. Purification and characterization of a salt-activated and organic solvent-stable heterotrimer proteinase from Virgibacillus sp. SK33 Isolated from Thai Fish Sauce. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2010;58:248–256. doi: 10.1021/jf902479k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spring S., Ludwig W., Marquez M.C., Ventosa A., Schleifer K.-H. Halobacillus gen. nov., with descriptions of Halobacillus litoralis sp. nov. and Halobacillus trueperi sp. nov., and transfer of Sporosarcina halophila to Halobacillus halophilus comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 1996;46:492–496. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ventosa A., Nieto J.J., Oren A. Biology of moderately halophilic aerobic bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1998;62:504–544. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.2.504-544.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Z., Schwartz S., Wagner L., Miller W. A greedy algorithm for aligning DNA sequences. J. Comput. Biol. 2000;7:203–214. doi: 10.1089/10665270050081478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]