Abstract

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Introduction

Employees’ job satisfaction and commitment depends upon the leadership style of managers. This study clarifies further the relationships between leadership behaviors of managers and two employees’ work-related attitudes-job satisfaction and organizational at public hospitals in Iran. A better understanding of these issues and their relationships can pinpoint better strategies for recruiting, promotion, and training of future hospital managers and employees, particularly in Iran but perhaps in other societies as well.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted using self-administered questionnaires distributed among 814 hospital employees and managers through a stratified random sampling.

Results and discussion

The dominant leadership style of hospital managers was participative style. Hospital employees were moderately satisfied with their jobs and committed to their organization. Salaries, benefits, promotion, contingent rewards, interpersonal relationships and working conditions were the best predictors of job satisfaction among hospitals employees. Leadership, job satisfaction and commitment were closely interrelated. The leadership behavior of managers explained 28% and 20% of the variations in job satisfaction and organizational commitment respectively.

Conclusion

This study clarifies the causal relations of job satisfaction and commitment, and highlights the crucial role of leadership in employees’ job satisfaction and commitment. Nevertheless, participative management is not always a good leadership style. Managers should select the best leadership style according to the organizational culture and employees’ organizational maturity.

Key words: Leadership, Job satisfaction, Organizational commitment, Hospital

1. INTRODUCTION

Employees are the most important resources of healthcare organizations. The sustained profitability of an organization depends on its workforce job satisfaction and organizational commitment (1). Employees’ job satisfaction enhances their motivation, performance and reduces absenteeism and turnover (1- 4). Job satisfaction is an employee’s attitude about his or her job and the organization in which s/he performs the job. Employee job satisfaction is correlated with received salaries, benefits, recognition, promotion, coworkers and management support, working conditions, type of work, job security, leadership style of managers, and demographic characteristics such as gender, marital status, educational level, age, work tenure, and number of children (5-8).

Organizational commitment shows the psychological attachment of an employee to the organization (9). According to Meyer and colleagues (2002) there are three types of organizational commitment: Affective, Continuance and Normative Commitment. Affective commitment relates to an employee’s emotional attachment to the organization and its goals. Continuance commitment shows cognitive attachment between an employee and his or her organization because of the costs associated with leaving the organization. Finally, normative commitment refers to typical feelings of obligation to remain with an organization (10).

Leadership behavior of managers plays a critical role in employees ‘job satisfaction and commitment (5, 11, 12). Leadership as a management function is mostly related to human resources and social interaction. It is the process of influencing a group of people towards achieving organizational goals (13). Leadership is the ability of a manager to influence, motivate, and enable employees to contribute toward organizational success (14). Managers can utilize various leadership styles to lead and direct their employees including autocratic, bureaucratic, laissez-faire, charismatic, democratic, participative, transactional, and transformational leadership styles. There is no universal leadership style Different leadership styles are needed for different situations. Effective leader must know when to exhibit a particular approach.

Good human resource management drives employee satisfaction and loyalty (4, 15, 16). Effective human resource management can also have a significant effect on customer satisfaction. Satisfied and committed employees deliver better care, which results in better outcomes and higher patient satisfaction (17-19).

Very little research in the literature is available on the links between managers’ leadership behavior and employees’ job satisfaction and organizational commitment. These studies were mostly conducted in Western countries and limited to health care organizations. However, where job satisfaction and organizational commitment were investigated, leadership behavior of managers was not analyzed. This study aimed to overcome this gap by investigating these variables in a group of hospitals in Iran.

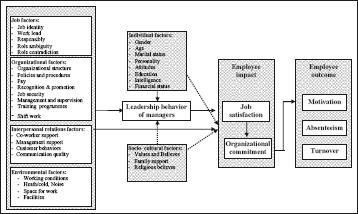

Research has been conducted to identify how leadership behaviors can be used to influence employees to achieve better organizational outcomes (20). However, there are no known studies related to the links between these subjects in the health care organizations of the country. This study addresses that need in Iran. The results of this research provide a better understanding of the relationship between leadership styles of managers and employees’ job satisfaction and commitment. Figure 1 presents a conceptual model of relationships between leadership, job satisfaction and organizational commitment. The model proposes that leadership is positively related to job satisfaction, which is positively related to organizational commitment. Therefore, I propose the following hypotheses:

Figure 1.

Hypothesized relationship between leadership, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment

Hypothesis 1: The greater the employees’ job satisfaction, the greater their commitment.

Hypothesis 2: There is a positive relationship between managers’ leadership style and employee’s job satisfaction and commitment.

2. METHODOLOGY

Purpose and objectives

This research investigates the relationship between perceptions of hospital managers and employees regarding the leadership behavior of hospital managers, and how this is related to the job satisfaction and organizational commitment of employees in Isfahan University Hospitals (IUHs), Isfahan, Iran.

The empirical setting

All University hospitals in Isfahan city (12) participated in this study.

Instruments

Separate questionnaires were sent to managers and employees. Employee questionnaire package contained a cover letter, and questionnaires related to employees’ job satisfaction, organizational commitment and the leadership style of hospital manager. Managers’ questionnaire package included a cover letter, their leadership styles, job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

The Job Satisfaction Scale (Specter 1997) utilized a Likerttype scale with six response alternatives ranging from “Strongly disagree” (weighted 1) to”Strongly agree” (weighted 6) for each of the 36 items to measure job satisfaction (21). Aspects of job satisfaction addressed are with: (a) pay, (b) promotion, (c) supervision, (d) fringe benefits, (e) contingent rewards, (f ) operating conditions, (g) co workers, (h) nature of work, and (i) communication (4 items in each domain).

Organizational Commitment Scale (Meyer et al. 1991) contained three eight-item components which were rated on a 6-point Likert type scale (from strongly disagree=1 to strongly agree=6). Aspects of organizational commitment addressed were affective, continuance, and normative commitment (22).

Mangers leadership scale (Likert, 1967) had 35 items of which 15 items determined a manager’s employee oriented dimension (consideration) and 20 items determined the task oriented dimension (initiating structure) of leadership style (23). Each statement included a five-point Likert scale (from very rarely =1 to often =5).

According to Likert (1967), the four distinct practices that leaders use to affect employee and organizational performance include: exploitative authoritative, benevolent authoritative, consultative and participative management.

Validation of research instruments

Survey questionnaires were originally developed in English. The author developed a Persian translation of these questionnaires by applying a sequential forward and backward translation approach. The final test version questionnaires were then pilot tested, using a random sample of 40 hospital employees (not included in the sample) and found to be well accepted and easy to fill in. The translated questionnaires were found to be understandable and could be completed in about 20 min.

Reliability of research instruments

Cronbach’s alpha was computed for each scale using the SPSS-11 statistical package. The reliability coefficient was .8749 for job satisfaction, .7784 for organizational commitment, .8767 for leadership style questionnaire from the view point of employees and .8139 for leadership style from the view point of managers’ questionnaires.

Data Collection

Stratified random sampling was used in this study. Using the following formula 950 persons were selected for this survey (N=6405, d=0.03, z= 1.96 and s= 0.51). Finally, 832 questionnaires were returned and from those, 814 questionnaires were completely filled (85.68 % return rate).

Analysis of Data

All data were analyzed using SPSS (the statistical package for the Social Sciences) software. In order to normalize the Likert scale on 1- 6 scales for each domain of job satisfaction and commitment questionnaires, the sum of raw scores of items in each domain was divided by the numbers of items in each domain and for overall job satisfaction and commitment, sum of raw scores of items were divided by 36 and 24 respectively. The possible justified scores were varied between 1 and 6. Scores of 2 or lower on the total scale indicate very low, scores between 2 and 2.99 indicate low, scores between 3 and 3.99 indicate moderate, scores between 4 and 4.99 indicate high and scores of 5 or higher indicate very high job satisfaction or organizational commitment. The scores of employee oriented and task oriented dimensions of leadership were varied between 15-75 and 20- 100. Higher scores in the domains indicate more employee oriented or more task oriented managers.

3. RESULTS

Data were collected from 814 persons including 665 employees, 127 first line managers (head of departments), 11 middle managers (hospital managers) and 11 senior managers (hospital presidents). As Table 1 shows about half of the respondents were males (48.4%). The majority (n=340) of participants ranged between 31 and 40 years of age. Approximately 82% (n=667) of the participants were married and 39.9% (n=325) had earned Bachelor’s degrees. Additionally, 51.5%, 87.4 %, 90.9% and 90.9% of employees, first line, middle and senior managers had permanent employment. The mean age for employees, front line, middle and senior managers were 34, 42, 46 and 45 years respectively. Employees, front line, middle and senior managers on the average, had 11, 19, 20 and 18 years of working experiences respectively. Front line, middle and senior managers on the average had 9, 12 and 9 years of managerial experiences respectively.

Table 1.

percentage of participants and the mean score of their job satisfaction and organizational commitment

| Demographic Parameters\The mean score of Job satisfaction and Commitment | percent | Job satisfaction | organizational commitment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Sex: | |||||

| Male | 48.4 | 3.28 | 0.50 | 3.987 | 0.50 |

| Female | 51.6 | 3.23 | 0.56 | 3.976 | 0.49 |

| Marital status | |||||

| Single | 18 | 3.21 | 0.59 | 3.96 | 0.51 |

| Married | 82 | 3.27 | 0.52 | 3.99 | 0.49 |

| Education level | |||||

| Illiterate | 2.8 | 3.58 | 0.54 | 3.96 | 0.45 |

| Under diploma | 11.9 | 3.23 | 0.65 | 4.09 | 0.48 |

| Diploma | 7.6 | 3.28 | 0.59 | 4.04 | 0.48 |

| Post diploma | 24.8 | 3.21 | 0.58 | 4.00 | 0.41 |

| Bachelor of science | 39.9 | 3.24 | 0.62 | 3.95 | 0.49 |

| Master of science or doctor of medicine | 7.2 | 3.15 | 0.50 | 3.88 | 0.51 |

| Doctor of philosophy | 5.8 | 3.37 | 0.43 | 3.85 | 0.47 |

| Area of work | |||||

| Managerial and clerical | 19.1 | 3.32 | 0.59 | 3.93 | 0.45 |

| Ancillary or logistic | 13.3 | 3.44 | 0.43 | 3.96 | 0.50 |

| Therapeutic | 55.1 | 3.20 | 0.56 | 4.00 | 0.47 |

| Diagnostic | 12.5 | 3.24 | 0.47 | 4.04 | 0.46 |

| Age group | |||||

| Under 20 years | 0.4 | 4.04 | 0.33 | 3.93 | 0.53 |

| Between 20-30 years | 28.7 | 3.25 | 0.53 | 4.02 | 0.50 |

| Between 31-40 years | 41.8 | 3.21 | 0.54 | 3.95 | 0.48 |

| Between 41-50 years | 26.6 | 3.30 | 0.48 | 4.00 | 0.41 |

| Between 51-60 years | 2.5 | 3.50 | 0.69 | 4.14 | 0.46 |

| Work experience years group | |||||

| Under 1 year (6 months - 1 year) | 3.2 | 3.34 | 0.43 | 4.04 | 0.58 |

| Between 1-5 years | 24.8 | 3.29 | 0.48 | 3.97 | 0.51 |

| Between 6-10years | 20.7 | 3.20 | 0.53 | 3.88 | 0.46 |

| Between 11-15 years | 18.1 | 3.15 | 0.53 | 3.95 | 0.44 |

| Between 16-20 years | 13.8 | 3.32 | 0.51 | 4.02 | 0.42 |

| Between 21-25 years | 12.8 | 3.33 | 0.46 | 4.07 | 0.43 |

| Between 26-30 years | 6.6 | 3.34 | 0.65 | 4.15 | 0.44 |

| Received salaries | |||||

| < 1,500,000 RLS | 81.9 | 3.22 | 0.53 | 3.99 | 0.49 |

| > 1,500,000 RLS | 18.1 | 3.44 | 0.54 | 3.96 | 0.50 |

Hospital employees were satisfied overall with their job with a mean score of 3.26±0.56 on a 6 scale (moderate satisfaction) compared with the possible range from 1.52 to 5.61. Employees, first line, middle and senior managers scored a mean of job satisfaction of 3.21, 3.40, 3.97 and 3.73 respectively. The differences between values were statistically significant (p<0.05).

Within the nine items of the job satisfaction scale, the three dimensions of the job with which respondents were most satisfied were: supervision, nature of the job and co workers. Respondents were least satisfied with the benefits, contingent rewards, communication, salaries, working conditions, and promotion (see Table 3).

Table 3.

The mean score of employees & managers job satisfaction according to job satisfier factors

| Job satisfier factors \ The mean score of Satisfaction Job | Senior managers | Middle managers | First line managers | Employees | All |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pay | 3.04 | 3.63 | 2.75 | 2.64 | 2.67 |

| Promotion | 3.95 | 3.59 | 3.09 | 2.85 | 2.91 |

| Supervision | 4.29 | 3.36 | 4.77 | 4.71 | 4.69 |

| Fringe benefits | 2.75 | 2.34 | 1.91 | 1.92 | 1.93 |

| Contingent rewards | 2.72 | 3.29 | 2.76 | 2.37 | 2.44 |

| Working conditions | 2.65 | 3.06 | 2.64 | 2.78 | 2.76 |

| Co workers | 4.77 | 4.98 | 4.54 | 4.32 | 4.36 |

| Nature of work | 5.06 | 4.88 | 4.60 | 4.34 | 4.39 |

| Communication | 3.54 | 3.72 | 3.14 | 2.83 | 2.53 |

A difference existed in perceptions between employees and managers pertaining to what aspects of the job are important to employees’ job satisfaction. Employees reported that managers’ loyalty to employees, job security, good pay and good working conditions were the most important motivators for them. However, managers thought that sufficient salaries, recognition and job security were most important to employees.

The mean score of employees’ job satisfaction in general and specialized hospitals was 3.19 and 3.37 respectively. The differences were statistically significant (p=0.038). The mean score of employees’ job satisfaction in hospitals with the specialty in burn (3.08), psychiatry (3.29), and cancer (3.31) were low and in hospitals with the specialty in ophthalmology (3.42) and cardiology (3.52) was high. Employees in specialized hospitals receive more monetary benefits than those employees in general hospitals because of the type of expensive services provided to patients.

Employee’s job satisfaction in therapeutic and diagnostic departments was statistically lower than administrative and ancillary departments (p<0.01). The mean score of employees’ job satisfaction in the Central Storage Department (4.21), Secretarial Unit (4.05), Public Relations Office (3.91), Social Worker Office (3.90) and Material Supply Department (3.66) were high and in the Psychiatry Ward (2.55), Pediatrics Ward (2.63), dialysis Ward (2.75), Urology Ward (2.85) and Medical Records Department, (2.88) were low.

There was strong correlation between the job satisfaction of employees and their gender, marital status, age, tenure, organizational position and received salaries (p<0.01). There was no statistically significant correlation between job satisfaction of employees and their graduation levels and type of employment: permanent or contract employment (p>0.05).

In order to determine the main factors that cause satisfaction and/or dissatisfaction with work, the relationship between total job satisfaction and job satisfy factors was analyzed. Calculations of Spearmen’s ratios revealed the strongest correlation between total job satisfaction and such characteristics as salaries, .687; fringe benefits, .685; promotion, .673 and communication, .637. On the other hand work conditions, .468; nature of the job, .502; supervision, .536; and co workers, .554 had less effect on employees’ job satisfaction respectively. This relationship was statistically significant in all of cases (p<0.001).

The mean score of employees’ satisfaction of job factors and organizational factors related to job satisfaction was 4.39 and 3.05 on a 6 scale respectively. Organizational, job and individual factors overall explained 99.3 % of the variance in employees’ job satisfaction. Organizational factors explained the largest amount of the variance (94%), followed by job factors and individual factors. Regards to organizational factors, Pay explained the largest amount of the variance, followed by coworkers, promotion, communication, supervision and benefit.

The mean score of respondents’ organizational commitment was 3.98±0.49 on a 6 scale (moderate). The mean score of organizational commitment of employees, first line, middle and senior managers was 3.97, 4.07, 4.12 and 4.03 from 6 credits respectively. The mean score of affective, continuance, and normative commitment were 3.88±0.69, 3.74±0.61, and 4.32±0.38 respectively.

The mean score of organizational commitment in employees with relevant educational background towards their job was higher than those without any relevance. The differences between values were statistically significant (p=0.004). A negative association was seen between employees organizational commitment and their educational levels (r = -0.126, p=0.001). Significant differences were obtained between age, tenure, organizational position, type of employment, received salaries and organizational commitment (p<0.05). Temporary employment and Amount of salaries were significantly related to continuance commitment (p<0.05). The employee’s organizational commitment in therapeutic and diagnostic departments was higher than administrative and ancillary departments. The differences between values were statistically significant (p=0.009). Significant differences were not obtained between employees’ organizational commitment and their gender, and marital status. The Kruskal Wallis test revealed that the total organizational commitment scores was not differed among twelve hospitals (p=0.61). In correlation analysis between organizational commitment and its three dimensions, affective commitment, 0.809; continuance commitment, 0.741; and normative commitment, 0.417 respectively had positive and the highest effect on employees’ organizational commitment.

The results of the simultaneous multiple regression model indicate that Organizational, job and individual factors overall explained 54.5% of the variance in employees’ organizational commitment. Organizational factors explained the largest amount of the variance (46%), followed by job factors and individual factors. Employees’ characteristics explain a smaller amount of variation in commitment. This is primarily the result of the effect of the employee’s education, the more educated employee reporting less commitment.

The mean score of employee-oriented dimension of leadership style in first line, middle and senior managers were 52 ± 6.35, 54 ± 3.89, and 54 ± 5.00 (from 75 credit) respectively. The mean score of task-oriented dimension of leadership style in first line, middle and senior managers were 68± 9.25, 69± 6.70, and 70± 7.20 (from 100 credit) respectively. 0.78%, 4.74% and 94.48% of first line managers had Exploitative-Authoritative, Benevolent-Authoritative and Participative leadership styles. All middle and senior managers had a participative leadership style.

From the viewpoint of employees the mean score of hospital managers’ employee-oriented and task-oriented credits were 46 (out of 75 credits) and 65 (out of 100 credits). From the viewpoint of hospital managers’ the mean score of their employee-oriented and task-oriented credits were 54 and 69. The differences between values were statistically significant (p<0.001). In other words, from the view point of employees, hospital managers were more task-oriented and from the view point of the hospital managers themselves, they were more employee-oriented.

There was no correlation between leadership style of managers and their demographic variables except age and managerial experience years. Pearson correlation coefficients indicate a significant statistically relationship between hospital managers’ management experience years and their employee oriented (p= 0.024 and r=0.736) and task oriented (p= 0.023 and r=0.706) dimensions of leadership style.

There was a statistically significant relationship between employees’ job satisfaction and their organizational commitment (p<0.001 and r=0.623) indicating that the employees who are more satisfied with their job are also more committed to the health care service. This study observed an asymmetric relationship where satisfaction had a stronger effect on commitment than the reverse. Satisfaction with job identity, .589; supervision, .463; communications, .442; contingent rewards, .367; promotion, .344; fringe benefit, .242; salaries, .235 and Work conditions, .215 were found to have a significant relationship to organizational commitment. On the other hand, affective and continuance commitment had more effect on employees’ job satisfaction. There was a statistically significant correlation between the job satisfaction of employees and the leadership style of managers. This correlation between employees job satisfaction and employee-oriented and task-oriented dimensions of leadership style of hospital managers was at p<0.001 and p<0.01 levels. The correlation co efficient between employee oriented and task oriented dimensions of leadership style and employees’ satisfaction factors showed that the most positive co-efficiency was between supervision and employee oriented dimension and the most negative co-efficiency was between fringe benefits and task oriented dimension of leadership style of managers.

A positive, significant correlation was shown among managers’ leadership style and employees’ commitment (p<0.01). Leadership behaviors were positively correlated with affective commitment (strongest relationship) and normative commitment. However, a negative correlation existed with continuance commitment. The employee-oriented dimension of leadership had positive, statistically significant (p < .01) correlations with affective commitment and normative commitment. Task-oriented had negative statistically significant (p < .01) correlations with normative commitment.

Leadership behaviors explained 28% variance in employees’ job satisfaction and 20 % in their commitment. Employees’ oriented dimension of leadership explained the largest amount of the variance in these two variables.

4. DISCUSSION

This study revealed a positive link between job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Satisfied employees had higher levels of organizational commitment. The result supported hypothesis 1. This finding is consistent with the findings of other previous studies in health care settings (24-25). However, Draper et al.’s (2004) study showed a negative correlation between job satisfaction and dimensions of organizational commitment which is contrary to with the finding from the present study (26). These differing results may be due to the differences in culture and the use of different instruments to measure commitment.

Employees with higher occupational positions reported higher job satisfaction. This can be related to having more control over the job, more decision-making latitude, higher salaries and benefits linked to seniority and more social recognition. This study has also shown that there is a significant negative relationship between the education level of employees and their commitment with their organization. Those employees with fewer years of education revealed more continuance and normative commitment. Therefore, education was found to have an inverse relationship with organizational commitment.

Employees who work with patients reported less job satisfaction but more commitment in this study. Job rotation could possibly be a good strategy for improving job satisfaction of these employees. Job enrichment can also be used as a motivational strategy to satisfy these employees through providing opportunities for personal achievement, challenge and recognitions. Higher commitment in employees in these wards could be because of investigation of this concept in an Islamic country. Nursing and providing services for patients is strongly recommended in Islam.

Lack of respect and recognition was another reason for employees’ dissatisfaction. Recognition and respect are highly important especially for employees who are in direct contact with patients, families, and peers. Managers’ recognition for good performance boosts employees’ morale and increases their satisfaction. A supportive management style, demonstrated through open communication, respect and recognition improve the employees’ job satisfaction.

It has been noted in this study that leadership, job satisfaction and commitment are closely interrelated. The finding supports hypothesis 1. These findings are consistent with earlier studies in health care organizations that demonstrate the connection between job satisfaction (27, 28, 29) and organizational commitment (30, 31) with leadership. These findings suggest that there is a positive relationship between the employee-oriented leadership behaviors and both affective commitment and normative commitment.

The findings also showed that hospital managers mainly used participative leadership style. Hospital employees were moderately satisfied with their jobs and committed to their organization. Therefore, it can be said that participative leadership was not successful in Iranian public hospitals. It seems that managers have insufficient information about leadership styles. Mosadeghrad and Tahery (2004) in their research in Iranian public hospitals concluded that managers’ knowledge about leadership styles was low (32). Providing more information about leadership theories help managers understand the importance of applying the right leadership style in their organizations.

Participative leadership does not necessarily result in higher employees’ outcome. There are situational variables that affect the effectiveness of participative leadership. For instance, the effectiveness of participatory leadership can be examined from a cultural perspective. In low power distance cultures, participative leadership style is viewed as desirable and effective (33). However, power distance in Iran is high (34). Managers in high power distance culture do not provide job enrichment and empowerment and employees do not necessarily want the responsibilities (35). Managers in such a culture may use a more directive leadership style to communicate with their subordinates. Therefore, in high power distance cultures, participative leadership style could be viewed as weak and ineffective leadership style. Iranian employees do not expect their leaders to be participatory. They prefer the managers to develop a vision and communicate it to them. Since charismatic leaders help reduce uncertainty, there is a strong preference for visionary, honest, cooperative, generous, concerned, and modest leaders (36).

Organizational culture influences employees’ sense of engagement, identification and belonging and subsequently impact on their commitment. In an innovative, corporate and supportive culture, employees’ level of job satisfaction and commitment are high. Organizational culture can also affect leadership styles of managers. Iranian public hospitals tend to be bureaucratic, and hierarchical. According to Mosadeghrad and Malek pour (2004), 75% of Isfahan university hospitals had mechanistic and bureaucratic structures. Hospital managers should consider the structure and culture of the organization in choosing the appropriate leadership style (37, 38, 39, 40, 41).

Maslow’s (1954) believes that human needs form a five-level hierarchy ranging from physiological needs, safety, love, and esteem to self-actualization (42). According to Maslow’s theory of hierarchy of needs, once individuals have satisfied one need in the hierarchy, it ceases to motivate their behavior and they are motivated by the need at the next level up the hierarchy. In this study, employees’ job satisfaction in relation to their salaries and benefits and working conditions was low. Once these primary and basic needs are met, they would think about participating in management decision making processes. The participative management is not a good leadership style for these hospitals at the moment, unless managers meet their employees’ basic needs, improve employees’ organizational maturity, promote a culture of teamwork, cooperation and participation and upgrade organizational structure accordingly.

Hospital managers should understand the impact of varying leadership styles on employees’ job satisfaction and commitment level. Thus, education and training should be provided to develop effective leadership behaviors to have a more positive effect on their employees’ job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

5. CONCLUSION

Research regarding the impact of leadership style of hospital managers on employees’ job satisfaction and commitment is relatively new in Iranian health care organizations. The purpose of this study was to contribute to a better understanding of the relationship between leadership behaviors of managers and these two employees’ work-related attitudes. This research documented the level of job satisfaction and organizational commitment among employees and the type of leadership style of managers in Iranian hospitals. This research also contributed to the knowledge of factors influencing job satisfaction and organizational commitment. The findings added to emerging studies on the influence of leadership on organizational outcomes.

The findings showed that hospital employees were moderately satisfied with their jobs and committed to their organization. Employees were mostly dissatisfied with salaries, benefits, rewards, work conditions, and communication. Areas of dissatisfaction are signals for change. Eighteen variables were found to contribute significantly to variance in employees’ job satisfaction. These include demographic variables of age, years of work experiences, marital status, gender and organizational position, monthly salary, type of hospital, employees’ organizational commitment, leadership style of managers and the nine subscales of job satisfy factors, as indicted in Table 3. Factors that may influence the level of employees’ commitment are demographic variables of age, years of work experiences, educational levels, organizational position, and type of employment, monthly salary, leadership style of managers and the nine subscales of job satisfier factors, as indicted in Table 3. In this study, employee oriented leadership explained significant variance in employees’ job satisfaction and commitment.

The current research was limited to a group of public hospitals in Iran. Hence, the findings should be interpreted with caution. More studies of the Iranian health care employees especially within hospitals that are not as hierarchical as the public hospitals surveyed in the current study are needed. This study serves as a foundation for future studies in other countries. More studies which involve hospital employees from other countries would enrich the literature on hospital employees’ job satisfaction and commitment. The results of such studies can be very helpful in developing strategies to improve the global retention of hospital personnel.

Table 2.

The frequency percentage of employees and managers’ job satisfaction

| Respondents \ Percent of Jab satisfaction | very low | low | medium | high | Very High |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employees | 1.9 | 26.1 | 64.7 | 7.3 | - |

| Front line managers | - | 23.9 | 63.2 | 12 | 0.9 |

| Middle managers | - | 27.2 | 45.5 | 18.2 | 9.1 |

| Senior managers | - | 9.1 | 63.6 | 18.2 | 9.1 |

Table 4.

The frequency percentage of employees and managers’ organizational commitment

| Commitment subscales \ Percent of Commitment | low | medium | high | Very High |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affective commitment | 5.3 | 59.8 | 26.7 | 8.2 |

| Continuance commitment | 12.7 | 59.2 | 22.6 | 5.5 |

| Normative commitment | - | 15.5 | 68.9 | 15.6 |

| Overall organizational commitment | - | 52.2 | 43.3 | 4.5 |

REFERENCES

- 1.Lok P, Crawford J.The effect of organizational culture and leadership style on job satisfaction and organizational commitment, Journal of Management Development. 2004; 23(4): 321-338 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Đorđević B.Employee commitment in times of radical organizational changes, Economics and Organization. 2004; 2(2): 111-117 [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeConincka J, Bachmann D.An analysis of turnover among retail buyers, Journal of Business Research. 2005; 58: 874-882 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mosadeghrad AM, Ferlie E, Rosenberg D.A study of relationship between job satisfaction, organisational commitment and turnover intention among hospital employees. Health Services Management Research, 2008; 21 (4): 211-227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mosadeghrad AM, Yarmohammadian MH.A study of relationship between managers’ leadership style and employees’ job satisfaction. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance incorporating Leadership in Health Services, 2006; 19(2): xi-xxviii [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furnham A, Petrides KV, Jackson CJ, Cotter T.Do Personality Factors Predict Job Satisfaction? Personality and Individual Differences. 2002; 33(8): 1325-1342 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wittig PG, Tilton-Weaver L, Patry BN, Mateer CA.Variables related to job satisfaction among professional care providers working in brain injury rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2003; 25: 97-106 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seo Y, Ko J, Price JL.The determinants of job satisfaction among hospital nurses: a model estimation in Korea. Int J Nurs Stud. 2004; 41: 437-446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kate W, Masako T.Reframing organizational commitment within a contemporary careers framework, Cornell University, New York, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyer JP, Stanley DJ, Herscovitch L, Topolnyutsky L.Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2002; 61: 20-52 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiok Foong, Loke J.Leadership behaviors: effects on job satisfaction, productivity and organizational commitment, J Nurs Manag. 2001; 9(4): 191-204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu TF, Tsai MH, Fey YHm Wu RTY.A Study of the Relationship between Manager’s Leadership Style and Organizational Commitment in Taiwan’s International Tourist Hotels. Asian Journal of Management and Humanity Sciences. 2006; 1(3): 434-452 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skansi D.Relation of managerial efficiency and leadership styles: empirical study in Hrvatska elektroprivreda, Management. 2000; 5(2): 51-67 [Google Scholar]

- 14.House RJ, Javidan M.Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies, Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ingersoll G, Olsan T, Drew-Cates J.et al. Nurses’ job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and career intent. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2002; 32(5): 250-263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Redfern S, Hannan S, Norman I, Martin F.Work satisfaction, stress, quality of care and morale of older people in a nursing home. Health and Social Care in the Community. 2002; 10(6): 512-517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haas JS, Cook EF, Puopolo AL, Burstin HR.et al. Is the professional satisfaction of general internists associated with patient satisfaction? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2000; 15(2): 122-128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sit WY, Ooi KB, Lin B, Chong AYL.TQM and customer satisfaction in Malaysia’s service sector. Industrial Management & Data Systems. 2009; 109(7): 957-975 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang CC.The impact of human resource management practices on the implementation of total quality management: An empirical study on hightech firms. The TQM Magazine. 2006; 18(2): 162-173 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mosadeghrad AM.The role of participative management in hospital effectiveness & efficiency. Research in Medical Sciences. 2003; 8(3): 85-89 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spector PE.Job Satisfaction: Application, Assessment, Causes, and Consequences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyer JP, Allen NJ.Commitment in the Workplace: Theory, Research, and Application, Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Likert RL.New Patterns of Management, New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1967 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knoop R.Relationships among job involvement, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment for nurses. The Journal of Psychology. 1995; 129(6): 643-649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al-Aameri AS.Job satisfaction and organizational commitment for nurses. Saudi Medical Journal. 2000; 21(6): 531-535 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Draper J, Halliday D, Jowett Set al. NHS Cadet Schemes: student experience, commitment, job satisfaction and job stress. Nurse Education Today. 2004; 24(3): 219-228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McNeese-Smith DK.Job satisfaction, productivity and organizational commitment, the result of leadership. Journal of Nursing Administration. 1995; 25: 17-26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moss R, Rowles CJ.Staff nurse job satisfaction and management style, Nurs Manage. 1997; 28(1): 32-34 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morrison RS, Jones L, Fuller B.The relation between leadership style and empowerment on job satisfaction of nurses. Journal of Nursing Administration. 1997; 27(5): 27-34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chiok Foong, Loke J.Leadership behaviors: effects on job satisfaction, productivity and organizational commitment, J Nurs Manag. 2001; 9(4): 191-204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leach LS.Nurse executive transformational leadership and organizational commitment. J Nurs Adm 2005; 35(5): 228-237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mosadeghrad AM, Tahery H.The survey of managers’ knowledge about management’s styles in Isfahan Medical University Hospitals (IMUHs) at Isfahan, Iran, Grant NO. 82300, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu MY.Compare Participative Leadership Theories in Three Cultures, China Media Research. 2006; 2(3): 19-30 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hofstede G.Culture’s consequences: International differences in workrelated values. Newbury Park, CA, Sage, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aycan Z, Kanungo RN, Mendonca M, Yu K.et al. Impact of Culture on Human Resource Management Practices: A 10-Country Comparison. Applied Psychology: An International Review. 2000; 49 (1): 192-221 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yukl GA.Leadership in organizations. 6 ed Prentice Hall, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mosadeghrad AM, Malek Pour J.The survey of relationship between organizational culture and employees’ organizational commitment in Isfahan University Hospitals (IUHs) at Isfahan, Iran, Grant NO. 83121, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mosadeghrad AM, Ferdosi M, Afshar H, Hosseini Nejhad S.The Impact of Top Management Turnover on Quality Management Implementation. Med Arh. 2013. Apr; 67(2): 134-140 doi: 10.5455/medarh.2013.67.134-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saghaeiannejad SA, Bahrami S, Torki S.Job Characteristic Percepcion and Intrinsic Motivation in Medical Record Department Staff. Med Arh. 2013. Feb; 67(1): 51-55 doi: 10.5455/medarh.67.51-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alavi SS, Alaghemanden H, Jannatifard F.Job Security at Isfahan University of Medical Sciences: Implications on Employees and Types of Contracts. Mat Soc Med. 2013. Mar; 25(1): 64-67 doi: 10.5455/msm.2013.25.64-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tavakoli N, Jakanbakhsh M, Shahin A, Mokhtari H, Rafiei M.Electronic Medical Records in Central Polyclinic of Isfahan Oil Industry: a Case Study Based on Technology Acceptance Model. Acta Inform Med. 2013. Mar; 21(1): 23-25 doi: 10.5455/aim.2013.21.23-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maslow A.Motivation and Personality, Harper and Row, New York, 1954. [Google Scholar]