Abstract

Objective

To determine the effect of pre-injection ocular decompression by cotton swabs on the immediate rise in intraocular pressure (IOP) after intravitreal injections.

Methods

Forty-eight patients receiving 0.05-ml ranibizumab injections in a retina clinic were randomized to two anesthetic methods in each eye on the same day (if bilateral disease) or on consecutive visits (if unilateral disease). One method utilized cotton swabs soaked in 4% lidocaine applied to the globe with moderate pressure and the other 3.5% lidocaine gel applied without pressure. IOPs were recorded at baseline (before injection) and at 0, 5, 10, and 15 minutes after the injection until the IOP was ≤30 mmHg. The IOP elevations from baseline were compared after the two anesthetic methods.

Results

The pre-injection mean IOP (SD, mmHg) was 15.5 (3.3) before the cotton swabs and 15.9 (3.0) before the gel (p=0.28). Mean IOP (SD, mmHg) change immediately after injection was 25.7 (9.2) after the cotton swabs and 30.9 (9.9) after the gel (P=0.001). Thirty-five percent of gel eyes had IOP ≥50 mmHg compared to only 10% of cotton swab eyes immediately after the injection (P<0.001).

Conclusion

Decompressing the eye with cotton swabs during anesthetic preparation prior to an intravitreal injection produces a significantly lower IOP spike after the injection.

Keywords: intraocular pressure, intravitreal injection, eye decompression, anti-VEGF agent

INTRODUCTION

Repetitive intravitreal injections have become a common treatment modality in the management of many retinal diseases. Patients may receive injections as frequently as every 2 weeks.1 Since the globe is essentially a non-compliant sphere, injecting an additional volume produces an acute short-term IOP elevation which carries a well-recognized risk of short-term occlusion of the central retinal artery.2 It has been documented that significant, and at times extreme, IOP elevations are common but are transient, i.e. usually taking less than 30 minutes to return to baseline.2–6 However, elevated IOP has been reported to persist for 2 hours, and there is a report of a patient who required a 1-week course of glaucoma medication to control IOP after bevacizumab.6 High IOP may lead to disruption in retinal and optic nerve head blood flow and has the potential for direct mechanical damage to the optic nerve axons.7,8 Consequences of transient IOP elevations are unknown. Patients with history of glaucoma have been shown to take significantly longer to normalize IOP.4 It is conceivable that these significant rises in IOP, repeated every month for many years, may lead to permanent damage, especially in patients with pre-existing glaucoma. Some normotensive patients might also be susceptible to effects of repetitive IOP elevations, and these might be the patients who demonstrate sustained IOP elevation reported in the literature.9,10,11 While the long-term effects of repetitive IOP elevations need to be studied further, ways to minimize post-injection IOP elevation should be considered. Lowering pre-injection IOP with medications and ocular decompression has been suggested. 10,12

We conducted a prospective randomized clinical trial comparing IOP rise after 0.05-cc ranibizumab injections, where the same patients were subjected to two different pre-injection anesthetic methods, one involving decompression with cotton swabs soaked with 4% lidocaine and the other employing 3.5% lidocaine gel applied without decompression. This was done as part of a randomized clinical trial comparing pain control efficacy of the two anesthetic techniques, which has been published elsewhere.13 Secondary outcome measure was post-injection IOP change with and without pressure on the eye. These data are presented here.

METHODS

This prospective randomized clinical trial was approved by the Miami Veterans Affairs Medical Center Institutional Review Board and was HIPAA compliant. The study was registered with ClinicaTrials.gov (Identifier NCT01087489). Patients requiring frequent ranibizumab intravitreal injections for various indications as part of their routine clinical care were recruited to partake in this study. The primary goal of the trial was to compare pain control with two anesthetic techniques. IOP rise with and without globe decompression was a secondary outcome measure.

Patients requiring bilateral ranibizumab injections were randomly assigned to a different preparation method in each eye, and the injections were administered on the same day. Patients requiring unilateral ranibizumab injection were randomly assigned to one of the anesthetic methods and then received the alternate anesthetic prep with the next injection at a future visit.

The 4% liquid lidocaine applied with cotton swabs and 3.5% lidocaine gel were administered per standard protocols as described below.

4% liquid lidocaine preparation

Two drops each of 0.5% proparacaine, 4% lidocaine, and 5% liquid povidone-iodine were instilled, and a 10% povidone-iodine swab was gently applied to the lids and lashes. A standard style sterile speculum was placed between the lids. Five percent liquid povidone-iodine was then applied over the entire ocular surface. Next, three sterile cotton swabs soaked in liquid 4% lidocaine were applied with gentle pressure to the area designated for injection in the infero-temporal quadrant to produce a visible circular indentation on the globe. Each cotton swab was pressed against the eye for 60 seconds. The cotton swabs were alternated with an additional drop of 5% povidone-iodine to the chosen area of injection. The injection was then performed by the same treating physician (NG) according to the routine technique. A sterile caliper was used to mark the distance from the limbus, followed by a drop of 5% betadine to this area, and a 0.05-ml ranibizumab injection into the vitreous cavity using a sterile 32-gauge needle attached to a 1-ml syringe. A sterile cotton swab was then used to momentarily cover the site (without applying any pressure) as the needle was withdrawn to limit egress of the vitreous.

3.5% viscous lidocaine ophthalmic gel preparation

Two drops each of 0.5% proparacaine and 5% povidone-iodine were placed on the eye. Sixty seconds later, two drops of preservative-free 3.5% lidocaine hydrochloride ophthalmic gel (Akten™, Akorn Inc.) were placed over the ocular surface and into inferior fornix. The patient was asked to gently close the eye for 7 minutes. A 10% povidone-iodine swab was gently applied to the lids and lashes. A standard style sterile speculum was placed between the lids and the gel was rinsed from the eye with an antibiotic (polymixin or gentamicin). Five percent liquid povidone-iodine was then applied over the ocular surface and allowed to remain in contact with the eye for 60 seconds. Next, the injection was performed by the same treating physician (NG) according to the routine technique as described in the previous preparation, including momentarily covering the site of injection without applying any pressure on the globe as the needle was withdrawn.

Both preparations were performed by the same technician on the same patient to avoid variability in technique. The amount of appropriate ocular compression was gauged by creating a visible indentation in the area of swab application. Same speculum style was utilized in both methods, which was removed prior to the first post-injection IOP reading. The injections were given by the same treating physician. For both preparations, optic nerve perfusion was assessed by confirming post-injection finger-counting vision.

The intraocular pressure was recorded prior to any ocular manipulation (baseline) and immediately following the injection by the same technician as often as possible. IOP was monitored every five minutes until the reading decreased to ≤30 mmHg. No eyes received pressure lowering medication or anterior chamber paracentesis before or after the injection.

The Tonopen (Reichert Technologies, New York) was used for IOP measurements in order to minimize the effects on the cornea. Corneal staining was one of the outcome measures in the trial.13 The Tonopen has a relatively small surface area and does not require the use of fluorescein dye, unlike applanation tonometry. To improve measurement accuracy, the Tonopen was calibrated and the measurements were repeated until a reliability of 5% was achieved.

The IOP elevations from baseline were compared between anesthetic methods with paired t-tests. A P-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Software utilized for statistical analysis is IBM SPSS PASW Statistics Version 17.0.

RESULTS

Fifty-three patients were randomized based on power calculations. Three patients were excluded after randomization (one patient was withdrawn due to inability to be reached by telephone (required for pain control assessment surveys), one patient died before the second injection, and one patient had been enrolled in another VA study and was not allowed to also enroll in this study). Fifty patients completed the clinical trial.14 Two patients who were injected with 0.1-ml rather than 0.05 ml of ranibizumab were excluded from this analysis to avoid skewing results. One patient who received 0.1 ml bilaterally demonstrated post-injection IOP of 81 mmHg (gel) vs. 67 mmHg (cotton swabs). This patient briefly lost light perception with the gel method but recovered vision within few minutes, and no anterior chamber tap was required in any patient. The second patient was measured at 41 mmHg after cotton swabs (eye with the 0.1-ml) and 37 mmHg after gel (eye with 0.05-ml). This patient had pre-existing glaucoma. If these patients are included, the conclusions are the same.

The results presented are based on the 48 patients who had 0.05-ml ranibizumab injections. Patient demographics and ocular characteristics are shown in Table 1. Eighteen patients received bilateral ranibizumab injections on the same day and 30 patients received unilateral ranibizumab injections with anesthetic method randomly assigned at the first injection and the alternate method given at the next injection.

Table 1.

Demographics and Ocular History

| Variable | N (%) Unilateral (n=30) |

N (%) Bilateral (n=18) |

N (%) Total (n=48) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Mean (SD) Median (range) |

73 (11) 77.5 (42–90) |

77 (13) 82.5 (48–91) |

75 (12) 78.5 (42–91) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 28 (93%) | 18 (100%) | 46 (96%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White Non-Hispanic | 21 (70%) | 16 (89%) | 37 (77%) |

| African American | 2 (7%) | 1 (6%) | 3 (6%) |

| Hispanic | 7 (23%) | 1 (6%) | 8 (17%) |

| Ocular diagnosis | |||

| Age-related macular degeneration | 20 (67%) | 14 (78%) | 34 (71%) |

| Diabetic macular edema | 1 (3%) | 4 (22%) | 5 (10%) |

| Retinal vein occlusion | 5 (17%) | 0 | 5 (10%) |

| Central Serous Retinopathy | 1 (3%) | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| Irvine-Gass syndrome | 1 (3%) | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| Idiopathic choroidal neovascular membrane | 1 (3%) | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| Other form of macular edema | 1 (3%) | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| Pre-existing glaucoma* | |||

| Yes | 4 (13%) | 1 (6%) | 5 (10%) |

| Number of previous injections in either eye | |||

| Mean (SD) Median (range) |

17 (13) 13 (3–52) |

21 (17) 17.5 (2–72) |

18 (15) 14.5 (2–72) |

Pre-existing glaucoma includes those with ocular hypertension on glaucoma medications; it does not include other glaucoma suspects

Table 2 presents IOP before and immediately after injection of 0.05-ml of ranibizumab. IOP spiked significantly less when eyes were prepared with cotton swabs compression (P<0.001, paired t-test). Mean change in IOP (SD, range) was 30.9 mmHg (9.9, 13–56) after the gel and 25.7 mmHg (9.2, 7–49) after cotton swab preparation (P=0.001, paired t-test).

Table 2.

Intraocular pressure before and immediately after 0.05-ml ranibizumab injection after the lidocaine gel versus liquid lidocaine-soaked cotton swabs method

| Variable IOP (mmHg) |

Gel method Mean (SD) Range All patients† N=48 |

Cotton swabs method Mean (SD) Range All patients† N=48 |

P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| IOP before injection | 15.9 (3.0) 8 –24 |

15.5 (3.3) 9–24 |

0.28 |

| IOP immediately after injection | 46.8(10.5) 29–76 |

41.2 (9.9) 21–68 |

<0.001 |

| Change in IOP | 30.9 (9.9) 13–56 |

25.7 (9.2) 7–49 |

0.001 |

Paired t-test

excludes 2 patients who received 0.1-cc ranibizumab injection for one or both injections

Abbreviations:

IOP- intraocular pressure, SD- standard deviation

We also compared eyes with (n=5) and without (n=43) pre-existing glaucoma. All eyes with glaucoma were well controlled with drops. No statistically significant differences were found in IOP prior to injection or immediately after injection. Pre-injection mean IOP (SD) was 16.6 (4.3) mmHg in eyes with glaucoma and 15.8 (2.9) mmHg in eyes without glaucoma before the gel prep (P=0.6, t-test), and 16.6 (4.6) mmHg in eyes with glaucoma and 15.4 (3.2) mmHg in eyes without glaucoma before the cotton swab prep (P=0.4, t-test). Immediately after the gel preparation, the mean IOP (SD) was 46.0 (13.9) mmHg in eyes with glaucoma and 46.9 (10.2) mmHg in eyes without glaucoma (P=0.9, t-test). After cotton swab preparation, the mean IOP (SD) was 39.8 (9.8) mmHg in the eyes with glaucoma and 41.3 (10.0) mmHg in the non-glaucomatous eyes (P=0.7, t-test).

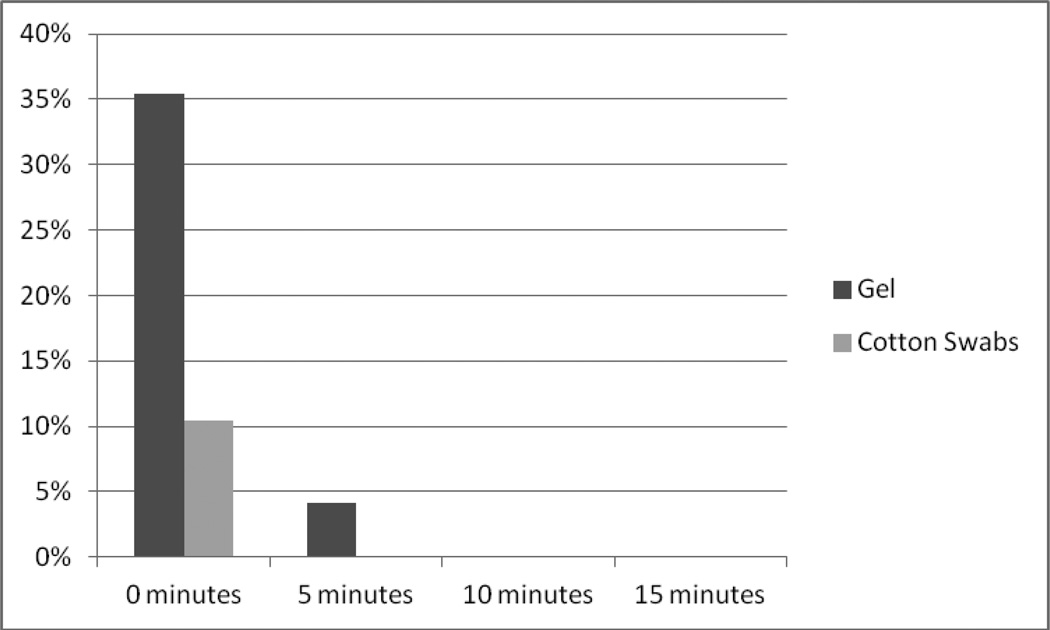

The IOP was measured every 5 minutes until it decreased to ≤30 mmHg. Figure 1 depicts percent of eyes with very high pressures, i.e. IOP ≥50 mmHg, at each time point. Thirty-five percent of gel eyes were at ≥50 mmHg compared to only 10% of cotton swab eyes immediately after injection (P<0.001, McNemar's test). IOP rapidly decreased, and 4% of gel eyes and none of the cotton swab eyes were at this high pressure at 5 minutes (P= 0.5, McNemar's test). No eyes were at ≥50 mmHg at 10 or 15 minutes.

Figure 1.

Percentage of Eyes Prepared with the Gel and with Cotton Swabs Methods with Post-injection IOP ≥ 50 mmHg vs. time after the injection.

A graph showing percentage of eyes prepared with gel and lidocaine-soaked cotton swabs with IOP ≥50 mmHg at zero through 15 minutes after 0.05-ml ranibizumab injection. Higher percentage of gel eyes prepared without softening by cotton swabs demonstrated IOP ≥ 50 mmHg immediately after the injection (P<0.001, McNemar's test) than the eyes softened by lidocaine-soaked cotton swabs.

Ninety-eight percent of gel eyes were ≥ 30 mmHg compared to 90% of cotton swab eyes immediately after injection (p=0.2, McNemar’s test). At 5 minutes 54% of the gel eyes and 44% of the cotton swab eyes had IOP ≥ 30 mmHg (p=0.4); at 10 minutes 17% versus 13% (P=0.7); and at 15 minutes 8% versus 2% (P=0.4).

DISCUSSION

Our data demonstrate that decompressing the eye with cotton swabs during anesthetic preparation prior to an intravitreal injection produces a significantly lower IOP spike after the injection. Short-term transient pressure elevation after anti-VEGF intravitreal injections, which introduce additional fluid into the eye, has been well described. 2–6,10 This phenomenon is not unique to anti-VEGF injections, as it is seen after any intravitreal injection in clinical practice, including steroid and antibiotic injections. Fortunately, the IOP has been shown to normalize within 30 minutes in most eyes.6. The long-term consequences of repetitive IOP elevations in patients undergoing anti-VEGF intravitreal therapy are unknown. Whether these short-term elevations play a role in the development of sustained IOP elevations requiring glaucoma therapy is also unknown. Anti-VEGF therapy has been shown to cause long-term, sustained IOP elevation in some patients. 11, 14–17 It is reasonable to suspect that some eyes are more susceptible to pressure damage due to limited blood supply or pre-existing glaucoma. Glaucoma eyes have been shown to take longer to return to pre-injection pressures. 4

A rise in IOP will be compensated by an increased rate of aqueous humor drainage via the trabecular meshwork and uveoscleral routes.18 The bulk of aqueous humor drainage occurs through the trabecular meshwork and Schlemm's canal, which communicates directly with the episcleral veins. The absorption through this route depends upon the gradient of the IOP to episcleral venous pressure. The rest of resorption occurs through the uveoscleral route, which relies on the pressure gradient from the anterior chamber to the interstitium of the sclera. In keeping with Goldmann’s analysis of aqueous humor flow 19, while the globe is indented and the IOP is elevated, there is a volume of fluid exit that exceeds steady inflow. When the external pressure is released, the reduced intraocular volume is reflected in a reduced IOP and should permit an injection to re-inflate the globe with less chance of an abnormally high IOP.

At the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, the standard anesthetic preparation for intravitreal injection involves three cotton swabs soaked in 4% liquid lidocaine, which are applied to the site of injection with moderate pressure. To our knowledge, there are no published data to document the effect of globe compression with cottons swabs on post-injection IOP elevation.

In the current prospective randomized clinical trial we show that compressing the eye with cotton swabs during anesthetic preparation resulted in significantly lower post-injection IOP elevations. Significantly fewer eyes prepared with compression exhibited IOP of ≥50 mmHg immediately after the injection. These findings resonate with the results of Kim and Jee who demonstrated that the Honan intraocular pressure reducer, applied to the eye at 30 mmHg for 10 minutes, significantly lowered pre-injection IOP and IOP immediately after intravitreal injection using tunneled scleral technique. 12 The IOP at 10 minutes post-injection was lower in the Honan group as well. The Honan balloon is a bulky and awkward device, which takes significantly greater time than the current method, and carries a risk of producing extremely high IOPs in eyes with higher initial pressure, such as in patients with glaucoma. 12 Therefore, other ways of decompressing the eye, such as gentle pressure with cotton swabs saturated with an anesthetic, should be considered.

The critics of pressure on the globe might raise a question of IOP increase during cotton swab application. Indeed we have measured a value of 68 mmHg during cotton swab pressure application (not part of this study), but the brief IOP increase during the prep can result in lower and shorter IOP spike after the injection. The critics might also suggest that patient-delivered pressure on the globe or a pressure device such as a mercury bag might be an alternative method of softening the eye prior to injection. While these methods can certainly be evaluated in a future study, the cotton swab method included in this study achieves both anesthesia and globe decompression prior to the injection.

Hollands et al showed that more than 10% of eyes prepared without decompression experience an IOP spike of above 50 mmHg after a 0.05-ml bevacizumab injection delivered with a 27 gauge needle.6 In our study, 0.05-ml ranibizumab was delivered with a 32 gauge needle causing 35.4% of gel eyes versus 10% of cotton swab eyes to exhibit an IOP of ≥50 mmHg (P<0.001). The IOP returned to lower values quickly in both groups, albeit more slowly in the gel group. Larger volume of injection (based on our clinical experience) and a smaller needle size4 result in statistically higher IOP elevation post-injection. Smaller needle bore size is believed to reduce pain and vitreous reflux after the injection, therefore smaller needles are commonly used in clinical practice. Unfortunately, 30- or 32-gauge needles results in higher post-injection IOPs after 0.05 ml injections than 27-gauge needles after 0.1 ml injections.4 At the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute and the Miami VA the 32 gauge needle is commonly used for all anti-VEGF agents, making globe decompression an important step in pre-injection globe preparation.

In conclusion, the current study provides objective data that decompressing the eye with cotton swabs during anesthetic preparation produces significantly lower post-injection pressure spikes. Whether repetitive IOP spikes have a long-term effect on patients' risk of developing glaucoma or produce further damage in patients with pre-existing glaucoma is unknown. Since many patients are likely to receive injections for many years, ophthalmologists should look for ways of minimizing potential harm. This study provides new information regarding the effects of mechanically decompressing the eye as a way to reduce IOP spike after intravitreal injections.

Acknowledgments

Research supported by an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc. and National Eye Institute core center grant P30 EY014801.The sponsor or funding organization had no role in the design or conduct of this research. The study was registered on the ClinicaTrials.gov with the following Identifier NCT01087489.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Stewart MW, Rosenfeld PJ, Penha FM, et al. Pharmacokinetic rationale for dosing every 2 weeks versus 4 weeks with intravitreal ranibizumab, bevacizumab, and aflibercept (vascular endothelial growth factor Trap-eye) Retina. 2012;32(3):434–457. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0B013E31822C290F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Falkenstein IA, Cheng L, Freeman WR. Changes of intraocular pressure after intravitreal injection of bevacizumab (avastin) Retina. 2007;27(8):1044–1047. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3180592ba6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharei V, Hohn F, Kohler T, et al. Course of intraocular pressure after intravitreal injection of 0.05 mL ranibizumab (Lucentis) Eur J Ophthalmol. 2010;20(1):174–179. doi: 10.1177/112067211002000124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim JE, Mantravadi AV, Hur EY, Covert DJ. Short-term intraocular pressure changes immediately after intravitreal injections of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor agents. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146(6):930–934. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gismondi M, Salati C, Salvetat ML, et al. Short-term effect of intravitreal injection of Ranibizumab (Lucentis) on intraocular pressure. J Glaucoma. 2009;18(9):658–661. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31819c4893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hollands H, Wong J, Bruen R, et al. Short-term intraocular pressure changes after intravitreal injection of bevacizumab. Can J Ophthalmol. 2007;42(6):807–811. doi: 10.3129/i07-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riva CE, Hero M, Titze P, Petrig B. Autoregulation of human optic nerve head blood flow in response to acute changes in ocular perfusion pressure. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1997;235(10):618–626. doi: 10.1007/BF00946937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yan DB, Coloma FM, Metheetrairut A, et al. Deformation of the lamina cribrosa by elevated intraocular pressure. Br J Ophthalmol. 1994;78(8):643–648. doi: 10.1136/bjo.78.8.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mathalone N, Arodi-Golan A, Sar S, et al. Sustained elevation of intraocular pressure after intravitreal injections of bevacizumab in eyes with neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00417-012-1981-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aref AA. Management of immediate and sustained intraocular pressure rise associated with intravitreal antivascular endothelial growth factor injection therapy. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2012;23(2):105–110. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32834ff41d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoang QV, Mendonca LS, Della Torre KE, et al. Effect on intraocular pressure in patients receiving unilateral intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor injections. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(2):321–326. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim KS, Jee D. Effect of the Honan intraocular pressure reducer on intraocular pressure increase following intravitreal injection using the tunneled scleral technique. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2011;55(6):632–637. doi: 10.1007/s10384-011-0088-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gregori NZ, Weiss MJ, Goldhardt R, et al. Randomized clinical trial of two anesthetic techniques for intravitreal injections: 4% liquid lidocaine on cotton swabs versus 3.5% lidocaine gel. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2012;9(7):735–741. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2012.685155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Good TJ, Kimura AE, Mandava N, Kahook MY. Sustained elevation of intraocular pressure after intravitreal injections of anti-VEGF agents. Br J Ophthalmol. 95(8):1111–1114. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2010.180729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adelman RA, Zheng Q, Mayer HR. Persistent ocular hypertension following intravitreal bevacizumab and ranibizumab injections. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 26(1):105–110. doi: 10.1089/jop.2009.0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kahook MY, Kimura AE, Wong LJ, et al. Sustained elevation in intraocular pressure associated with intravitreal bevacizumab injections. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2009;40(3):293–295. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20090430-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tseng JJ, Vance SK, Della Torre KE, et al. Sustained increased intraocular pressure related to intravitreal antivascular endothelial growth factor therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. J Glaucoma. 2012;21(4):241–247. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31820d7d19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morrison JC, TS A. Glaucoma - Science and Practice. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers Inc; 2003. Anatomy and physiology of aqueous humor outflow; pp. 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldmann H. Out-flow pressure, minute volume and resistance of the anterior chamber flow in man. Doc Ophthalmol. 1951;5–6:278–356. doi: 10.1007/BF00143664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]