Abstract

Research on coparenting documents that mothers' and fathers' coordination and mutual support in their parenting roles is linked to their offspring's adjustment in childhood, but we know much less about the coparenting of adolescents. Taking a family systems perspective, this study assessed two dimensions of coparenting, parents' shared decision-making and joint involvement in activities with their adolescents, and examined bidirectional associations between these coparenting dimensions and boys' and girls' risky behaviors and depressive symptoms across four time points (6 years) in adolescence. Participants were 201 mothers, fathers, and adolescents (M = 11.83, SD = .55 years of age at Time 1; 51 % female). Parents of sons shared more decisions, on average, than parents of daughters. On average, shared decision-making followed an inverted U shaped pattern of change, and parents' joint involvement in their adolescents' activities declined. Cross-lagged findings revealed that risky behavior predicted less shared decision-making, and shared decision-making protected against increased risky behavior for boys. For girls and boys, parents' joint involvement predicted fewer risky behaviors, and lower levels of risky behavior predicted higher levels of joint involvement. In contrast, boys' and girls' depressive symptoms predicted less joint involvement. The discussion centers on the nature and correlates of coparenting during adolescence, including the role of child effects, and directions for future research on coparenting during this developmental period.

Keywords: Adolescent development, Coparenting, Depressive symptoms, Family systems, Risky behaviors

Introduction

Coparenting is a family systems dynamic that encompasses mothers' and fathers' coordination of their parenting efforts and support for each other's parental role (Feinberg 2002). A principle of a family systems framework is that families reorganize in response to change; as such, studying families during periods of developmental transition can provide insights into family processes (Minuchin 1985). Consistent with this principle, past research has focused oncoparenting in families at the transition to parenthood and in early childhood as mothers and fathers navigate parenting challenges as a team for the first time (McHale et al. 2004; Van Egeren 2004).

Offspring's adolescence is another developmental period when parents face new challenges. Youth's increasing autonomy and risk for behavior problems may require parents to develop new parenting strategies (Steinberg 2001), and as a result, parents of adolescents may need to renegotiate their coparenting relationship to move their parental practices onto the same page. However, we know very little about coparenting during this developmental period, although scholars have argued that the nature and correlates of coparenting are likely to differ for families with adolescents (Feinberg et al. 2007).

Coparenting frameworks (e.g., Feinberg 2002) direct attention to inter-parental consistency in childrearing practices and joint involvement in parenting as two key dimensions, and both of these may be relevant to parenting adolescents. Thus, in keeping with the family systems tenet that development brings new challenges to families, the first goal of this study was to examine two dimensions of coparenting that may be especially relevant to adolescents–parents' shared decision making and joint involvement in activities with their child—and chart patterns of change in these dimensions of coparenting across 6 years of the offsprings' adolescence. Given the earlier onset of puberty for girls relative to boys and the different practices that parents enact with sons and daughters (Kerig et al. 1993), we also explored gender differences in these coparenting dimensions.

In addition to describing changes in dimensions of coparenting across offsprings' adolescence, a second goal of this study was to examine potential bidirectional influences between each coparenting dimension and adolescents' risky behaviors and depressive symptoms. A second tenet of family systems theory is that family subsystems are mutually influential; as such, development in adolescence may contribute to novel social dynamics between parents and their offspring. Some research has shown that mothers' and fathers' parenting and coparenting have implications for adolescent adjustment (Feinberg et al. 2007). In contrast, little is known about the reverse direction of effect, that is, the implications of youth adjustment for coparenting. This is especially true for families of adolescents given the limited coparenting research focused on this developmental period. Research on the role of adolescent adjustment for family dynamics shows, however, that adolescents' behavior problems can interfere with effective parenting (Kerr and Stattin 2003) and marital harmony (Cui et al. 2007). Thus, to advance the understanding of mutual influences within families. we assessed bidirectional links between parents' coparenting, indexed by their shared decision making and joint involvement, and adolescent adjustment.

Dimensions of Coparenting in Families of Adolescents

Normative stressors and transformations in family processes that often accompany adolescence mean that adolescent development may bring new challenges to coparenting. Indeed, coparenting may be quite different in adolescence than in families with young children. Whereas coparenting young children requires a high level of moment-to-moment cooperation, this type of teamwork is less important in coparenting pre-adolescents who are developing independence from their parents (Margolin, et al. 2001). Prior research, however, has not examined coparenting dimensions that pertain to adolescents' unique developmental needs (Feinberg et al. 2007). Thus, to advance understanding of coparenting during offsprings' adolescence we examined dimensions of coordinated parenting that may be pertinent during this developmental transition.

Coparenting frameworks (Feinberg 2002) highlight dimensions including inter-parental consistency on childrearing practices and joint involvement in parenting, both of which may be relevant during offsprings' adolescence, even as coparenting manifestations change. We grounded our efforts to identify dimensions of coparenting of significance in adolescence in conceptualizations of parent–child relationships and youth development during this period (Collins et al. 1997). A central phenomenon of adolescence is the development of autonomy; as youth mature and gain independence, parents allow adolescents more freedom in decision-making (Collins et al. 1997). Because most prior research on decision-making is based on reports from mothers and youth (e.g., Smetana et al. 2004), however, almost nothing is known about inter-parental consistency in mothers' and fathers' decision-making surrounding their adolescents' activities and experiences. As with other parenting practices, mothers and fathers may not always be in agreement with respect to who makes decisions as they renegotiate their practices around new parenting challenges. In this study, we assessed mothers' and fathers' shared decision-making pertaining to their offsprings' daily experiences (e.g., social life, chores, homework) as reflective of their agreement and support in their parenting roles, and one key dimension of coparenting adolescents.

Another dimension of coparenting that has potential significance in adolescence is mothers' and fathers' time in shared activities or their joint involvement with youth. Even as youth pursue autonomy, maintaining close ties to parents remains important for adolescents' development and adjustment, and youths' shared time with their parents is a manifestation of such ties (Collins et al. 1997). Research and theory on coparenting indicate that mothers' and fathers' joint activities with their children reflect their mutual commitment to coparenting, whereas imbalances in coparents' involvement may mark coalitions or divided loyalties within the family (Feinberg 2002). For example, observational studies with young families reveal that shared time with both parents present constitutes positive coparenting (McHale and Rasmussen 1998). Although adolescents spend less time at home and are more involved with the world beyond the family (Larson et al. 1996; Youniss and Smollar 1985), time spent with parents remains important for adjustment (Barnes et al. 2007; Crouter et al. 2004; McHale et al. 2001). Accordingly, as a second dimension of coparenting, we focused on mothers' and fathers' joint involvement or time in shared activities with adolescents.

Adolescent gender may have implications for both coparenting and youth adjustment. Prior research reveals mixed results on the role of gender in coparenting. Although gender differences are not evident in studies of young children (Floyd and Zmich 1991; Stright and Bales 2004), among school-aged children, boys tend to be more involved in and exposed to inter-parental discord than girls (Margolin et al. 2001; McHale 1995). Thus, the role of youth gender in coparenting may change across development. And, consistent with a gender intensification perspective, the role of gender for family dynamics and youth adjustment may become more pronounced in adolescence (Hill and Lynch 1983). Indeed, prior work reveals gender differences in parental knowledge (Bumpus et al. 2001) and parent-adolescent relationship qualities (Shanahan et al. 2007). In addition, youth adjustment problems become increasingly gendered, with boys experiencing faster increases in externalizing behavior (Zahn-Waxler 1993), and girls experiencing more rapid increases in internalizing behaviors (Angold and Rutter 1992). For these reasons, we were interested in whether associations between coparenting dimensions and youth adjustment differed for boys versus girls.

Evidence for Reciprocal Relationships Between Coparenting and Adolescent Adjustment

Research on coparenting establishes that inter-parental dynamics are important for early childhood adjustment. Low levels of coparental consistency and support have been linked to higher externalizing behavior problems among pre-school aged children (McHale and Rasmussen 1998; Schoppe et al. 2001), and inter-parental differences in warmth have been related to more internalizing problems for school-aged sons and daughters and externalizing behavior problems for sons (McConnell and Kerig 2002). Imbalances between mothers' and fathers' involvement with offspring have been linked to children's anxiety and aggression (McHale and Rasmussen 1998). From the smaller set of studies that have examined coparenting in families of adolescents, there is some evidence that coparental conflict about childrearing issues puts youth at risk for externalizing behavior problems (Baril et al. 2007) and delinquency (Feinberg et al. 2007). Less well understood, however, are the implications of positive and coordinated coparenting for adolescent adjustment. Accordingly, we expanded on the coparenting literature by testing whether parents' shared decision making and joint involvement were linked to lower levels of risky behavior and depressive symptoms in adolescence.

There is little evidence of children's influences on coparenting (Lindsey et al. 2005; Stright and Bales 2004). However, given adolescents' increasingly active role in family processes, they may be influential in coparenting dynamics. In support of the family systems tenet that subsystems within families are bidirectional, we draw on research that documents youth-driven effects on family functioning. For example, there is evidence that adolescent behavior problems interfere with parental knowledge of youth's whereabouts when parents become discouraged and withdraw from parenting responsibilities (Kerr and Stattin 2003; Laird et al. 2003). One study examined the role of youth's behavior problems for coparenting: Cui et al. (2007)found that adolescents' internalizing and externalizing behaviors exacerbated inter-parental conflict about childrearing, which, in turn, had a negative impact on marital satisfaction. This study provided an important contribution to our understanding of coparenting, lending support to the idea that adolescent behaviors can interfere with marital functioning through their effects on coparenting dynamics. We built on this work and other past research by examining the longitudinal associations between adolescent risky behaviors and dimensions of coparenting. Specifically, using four waves of data, we tested two directions of effect to determine whether youth's risky behaviors and depressive symptoms predicted coparenting, and/or whether dimensions of coparenting predicted adolescent adjustment problems, and we examined whether there were gender differences in these associations.

The Present Study

This study expanded the scope of research on coparenting in addressing two goals. The first was to explore the longitudinal course of two dimensions of coparenting that may be relevant in adolescence, namely mothers' and fathers' shared decision-making and joint involvement, across 6 years of their firstborns' adolescent development. We examined coparenting among firstborns to understand changes in coparenting the first time parents face the challenges of rearing an adolescent. We also explored the role of youth gender in patterns of change given research and theory on the intensification of gender socialization in adolescence. Given the lack of prior research on coparenting during adolescence and mixed evidence for the role of child gender in coparenting, however, we did not advance hypotheses about patterns of change over time or gender differences in these patterns. Our second goal was to examine the reciprocal links between dimensions of coparenting and adolescent adjustment, and gender differences in these associations. Based on prior research, primarily in early and middle childhood, we expected that mothers' and fathers' shared decision-making and joint involvement would be related negatively to adolescent risky behavior and depressive symptoms. In turn, based on research showing that adolescent adjustment problems can disrupt inter-parental dynamics, we expected that risky behavior and depressive symptoms would be linked to lower levels of these positive dimensions of coparenting. Finally, given increasing gender differences in adjustment problems in adolescence, we expected links between coparenting and risky behavior would be stronger for boys and associations between coparenting and depressive symptoms would be stronger for girls.

Methods

Participants

Data came from a longitudinal study of family relationships and individual development in 201 two-parent European American families with offspring in middle childhood and adolescence. Families were recruited via letters sent home from schools in small urban and rural districts in a northeastern state. The letters described the study and criteria for participation: always-married parents with a firstborn child in the fourth or fifth grade, with a sibling who was 1–4 years younger. Interested families returned a postcard, and a follow-up interview determined whether they met the criteria to participate in the study. We were unable to determine how many families received letters and met the study criteria but did not volunteer to participate. However, among families who returned the postcard and were eligible, over 90 % agreed to participate.

Data collection began in 1995–1996. To capture changes in coparenting and adjustment across multiple years of adolescence, our analyses used data from mothers, fathers, and offspring at years 2, 3, 6, and 7 of the study (referred to as Times 1, 2, 3, and 4, hereon) when offspring were approximately 12, 13, 16, and 17 years old, respectively, and when the measures of interest were collected. Sample attrition was minimal: Over the study period, 10 families withdrew and an additional 4 youth and 13 fathers did not participate at wave 7, and were missing data on some occasions as a result. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) determined that parents and youth with missing occasions of measurement did not differ from those with complete data on their reports of any variables of interest, so all 201 families were retained in the analyses.

At Time 1, youth averaged 11.83 years of age (SD = .55), and ranged in age from 10.41 to 13.72. The sample was approximately equally divided by gender (n = 103 girls). Families were generally working and middle class. At Time 1, the mean education level for mothers was 14.63 years (SD = 2.11) and fathers' education, 14.72 years (SD = 2.40), with a score of 14 representing vocational training/some college and a score of 15 representing Associates degree. Almost all parents were employed (92 % of mothers and 100 % of fathers). Fathers worked an average of 47.36 h/week (SD = 11.11), and mothers, 29.28 h/week (SD = 15.23). At Time 1, the mean household income was $63,355 (SD = 31,471). Average family size was 4.54 (SD = .76). There was no significant change in family size, education, work hours, or income across the study period.

Procedure

We used two data collection procedures. First, we conducted annual home interviews with mothers, fathers, and youth. Informed consent/assent was obtained, and families received a $100 honorarium at Times 1 and 2, and $200 at Times 3 and 4. Then, family members were interviewed separately about their family relationship experiences and personal qualities during the past year unless a different time frame is noted. Home interviews generally lasted 2–3 h.

The second data collection procedure was used to obtain information about youth's daily activities. In the 3–4 weeks following annual home interviews, trained interviewers used a detailed script to conduct 7 telephone interviews with youth (5 on weekday evenings, 2 on weekend evenings). During these calls, youth reported on their daily activities outside of regular school hours; the type of activity, how long the activity lasted, and with whom they had engaged in each activity were recorded. Mothers and fathers were interviewed separately by phone on 3 weeknights and 1 weekend night. These calls focused on parents' own activities and their knowledge about youth's daily activities and whereabouts. Calls were scheduled in the evening so that family members could report on almost all activities that occurred during that day. Across study waves, 28 youth, 48 fathers, and 33 mothers were missing some phone data. Families with missing phone data did not differ from those with complete data on any background characteristics.

Measures

Parents' Shared Decision-Making

Shared decision-making was assessed during the home interviews at each time point using an adapted measure of adolescent decision-making (Dornbusch et al. 1985). Mothers and fathers were asked to “think about how decisions have been made during the past year in different areas of your child's life”, and indicated the family member(s) who made decisions in each of eight domains: chores, appearance, homework/schoolwork, social life, bedtime/curfew, health, choosing activities, and money. Response options were: (1) child only, (2) mother, (3) father, (4) both parents, (5) father and child, (6) mother and child, (7) parents and child, (8) other person(s), and (9) nobody. Because “other person” and “nobody” were never endorsed, these options were not included in scoring. We also excluded the “child only” response, reasoning that decisions that involved “both parents” would be the purest measure of coparenting. (We tested models in which “child only” reports were treated as coparenting. Results were consistent when “child only” was included and excluded,” and thus we report results that exclude “child only” responses.) For the analyses, responses were coded as 0 when only one parent was involved in the decision (i.e., mother only, father only, father and child, mother and child), and 1 when both parents were involved in decision-making (i.e., both parents, both parents and child). Scores were summed across domains to create an index ranging from 0 (parents made no decisions together in any domain) to 8 (parents made decisions together in every domain). Mothers' and fathers' ratings were correlated moderately to high, ranging from r = .54 to r = .70 across phases, with the correlation between parents increasing over time. Thus, we averaged their scores to create one indicator of shared decision-making at each year of the study.

Joint Involvement

Parents' joint involvement with offspring was measured using youth reports from the nightly telephone interviews. We aggregated youth reports across all activities and all 7 calls to create a measure of the time (in min) that youth spent with both their mothers and fathers present. Scores reflect mother-father-child involvement if both parents and target youth were present, regardless of whether others (e.g., sibling, friend) were involved in the activity as well.

Risky Behaviors

We assessed externalizing behaviors using the 18-item Risky Behavior Scale (Eccles and Barber 1990). Youth reported on the extent of their involvement in risk taking behaviors (e.g., “Drink alcohol without your parents' permission”) using a scale of 1 = never to 4 = more than 10 times in the past year. Items were summed with higher scores indicating more risk taking behaviors. Cronbach αs ranged from .71 to .87 for girls, and from .72 to .89 for boys.

Depressive Symptoms

Youth depressive symptoms were measured using the Children's Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs 1985). For 26 items (an item on suicide ideation was dropped from the original scale), youth were asked to choose among three sentences, the one that best described them over the past week (e.g., “I am sad once in a while” or “I am sad many times” or “I am sad all the time”). Items were summed, with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms. Across time points, alphas ranged from .78 to .89 for girls, and from .70 to .86 for boys.

Youth and Family Background Characteristics

Parents reported on family demographics at Time 1, including youth age, youth gender, parent education level, family income, and household size.

Results

Coparenting in Families of Adolescents

The results are organized around our research goals. Our first step was to describe patterns of change in dimensions of coparenting. Descriptive statistics for study variables are shown in Table 1, and correlations are shown in Table 2. On average, parents reported shared decision-making in more than half of the eight domains. Mothers, fathers, and adolescents averaged about 4 h of time together/week, or about 34 min/day. Together, descriptive findings suggest that these types of coparenting are relatively prominent in families of adolescents. Scores for the two coparenting dimensions were not correlated highly, lending further support to our decision to treat them as separate dimensions.

Table 1. Means and standard deviations (SDs), for study variables.

| Variables | Girl Mean (SD) | Boy Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Shared decision-making | ||

| Time 1 | 5.57 (1.73) | 5.96 (1.55) |

| Time 2 | 5.74 (1.53) | 6.30 (1.35) |

| Time 3 | 4.64 (2.28) | 5.05 (2.22) |

| Time 4 | 4.44 (2.27) | 4.72 (2.35) |

| Joint involvement (min/week) | ||

| Time 1 | 324.12 (192.24) | 377.18 (265.99) |

| Time 2 | 304.15 (191.78) | 326.59 (226.30) |

| Time 3 | 249.23 (225.21) | 268.99 (230.59) |

| Time 4 | 231.89 (190.58) | 221.67 (214.02) |

| Risky behavior | ||

| Time 1 | 20.19 (2.05) | 22.50 (3.76) |

| Time 2 | 20.99 (3.38) | 23.87 (5.96) |

| Time 3 | 24.61 (6.36) | 28.82 (8.92) |

| Time 4 | 26.52 (7.74) | 29.40 (9.10) |

| Depressive symptoms | ||

| Time 1 | 5.24 (4.31) | 4.75 (3.99) |

| Time 2 | 4.89 (4.16) | 4.56 (3.58) |

| Time 3 | 8.23 (6.80) | 6.28 (5.70) |

| Time 4 | 7.76 (6.60) | 5.86 (5.77) |

N = 103 girls, N = 98 boys

Mean age at Time 1 = 11.82 (SD = .55), Time 2 = 12.82 (SD = .56), Time 3 = 16.46 (SD = .79), Time 4 = 17.34 (SD = .79)

Table 2. Bivariate correlations for dimensions of coparenting and adolescent adjustment.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Shared decision-making T1 | – | .17 | .01 | .02 | .69 | .11 | .03 | −.04 |

| 2. Joint involvement T1 | .10 | – | .10 | .14 | .22 | .44 | .13 | .06 |

| 3. Risky behaviors T1 | .19 | −.11 | – | .29 | −.08 | .07 | .73 | .34 |

| 4. Depressive symptoms T1 | .13 | −.18 | .43 | – | −.10 | .02 | .19 | .52 |

| 5. Shared decision-making T2 | .59 | .07 | .14 | .09 | – | .20 | .06 | −.11 |

| 6. Joint involvement T2 | .16 | .41 | −.03 | −.03 | .00 | – | .11 | −.01 |

| 7. Risky behaviors T2 | .20 | .01 | .33 | .09 | .13 | .11 | – | .37 |

| 8. Depressive symptoms T2 | .12 | .02 | .23 | .51 | .06 | .04 | .33 | – |

| 9. Shared decision-making T3 | .55 | .08 | .01 | .04 | .54 | .12 | −.00 | .07 |

| 10. Joint involvement T3 | .15 | .07 | −.03 | −.23 | .04 | .05 | −.05 | −.17 |

| 11. Risky behaviors T3 | −.05 | −.07 | .23 | .08 | −.01 | −.13 | .30 | .22 |

| 12. Depressive symptoms T3 | −.04 | −.14 | .32 | .53 | −.02 | −.07 | .16 | .39 |

| 13. Shared decision-making T4 | .44 | .02 | .15 | .14 | .43 | .06 | −.03 | .03 |

| 14. Joint involvement T4 | .25 | .23 | −.02 | −.15 | .09 | .24 | .03 | −.04 |

| 15. Risky behaviors T4 | .06 | .03 | .32 | .14 | .09 | −.05 | .28 | .19 |

| 16. Depressive symptoms T4 | .11 | −.08 | .36 | .54 | .12 | .02 | .08 | .32 |

|

| ||||||||

| Variables | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

|

| ||||||||

| 1. Shared decision-making T1 | .41 | .21 | −.02 | −.02 | .33 | .09 | −.01 | −.02 |

| 2. Joint involvement T1 | .14 | .25 | .02 | −.04 | .23 | .22 | −.05 | −.07 |

| 3. Risky behaviors T1 | −.05 | −.12 | .55 | .17 | −.10 | −.14 | .58 | .13 |

| 4. Depressive symptoms T1 | .05 | −.02 | .19 | .25 | .02 | −.14 | .13 | .34 |

| 5. Shared decision-making T2 | .38 | .17 | .01 | .01 | .28 | .12 | .02 | −.02 |

| 6. Joint involvement T2 | .01 | .15 | .04 | .28 | .04 | .03 | .13 | .19 |

| 7. Risky behaviors T2 | −.07 | −.11 | .55 | .23 | −.23 | −.05 | .59 | .18 |

| 8. Depressive symptoms T2 | .02 | −.28 | .29 | .35 | −.05 | −.02 | .23 | .31 |

| 9. Shared decision-making T3 | – | .37 | .03 | .02 | .74 | .34 | .00 | −.02 |

| 10. Joint involvement T3 | .25 | – | −.20 | −.06 | .35 | .48 | −.14 | .09 |

| 11. Risky behaviors T3 | −.13 | −.27 | – | .38 | −.07 | −.25 | .81 | .32 |

| 12. Depressive symptoms T3 | −.15 | −.34 | .51 | – | −.09 | −.05 | .26 | .73 |

| 13. Shared decision-making T4 | .64 | .20 | −.09 | .01 | – | .40 | −.10 | −.07 |

| 14. Joint involvement T4 | .32 | .45 | −.26 | −.27 | .14 | – | −.17 | −.09 |

| 15. Risky behaviors T4 | −.10 | −.19 | .85 | .55 | .06 | −.22 | – | .34 |

| 16. Depressive symptoms T4 | −.03 | −.23 | .23 | .65 | .09 | −.16 | .37 | – |

T1–T4 refer to time points of measurement; correlations for boys above the diagonal, correlations for girls below the diagonal. Correlations higher than r = .12 are significant, p < .05

To examine the trajectory of each coparenting dimension across adolescence, we used multilevel modeling (MLM). This approach extends multiple regression to account for dependencies in the data (i.e., within person over time) and allows for an unbalanced design. Thus, we were able to use youth age as an index of time to detect developmental patterns in coparenting that might have been obscured by using the study year as the metric of time. Specifically, we tested a two level model for each coparenting dimension using SAS Proc Mixed. The Level 1, or within-person model, captured changes in shared decision-making and joint involvement in relationship to youth age. We included a linear and quadratic age polynomial at Level 1. Level 2 estimates are at the between-person level. Here we included offspring gender to examine whether average coparenting levels or patterns of change over time differed for boys and girls.

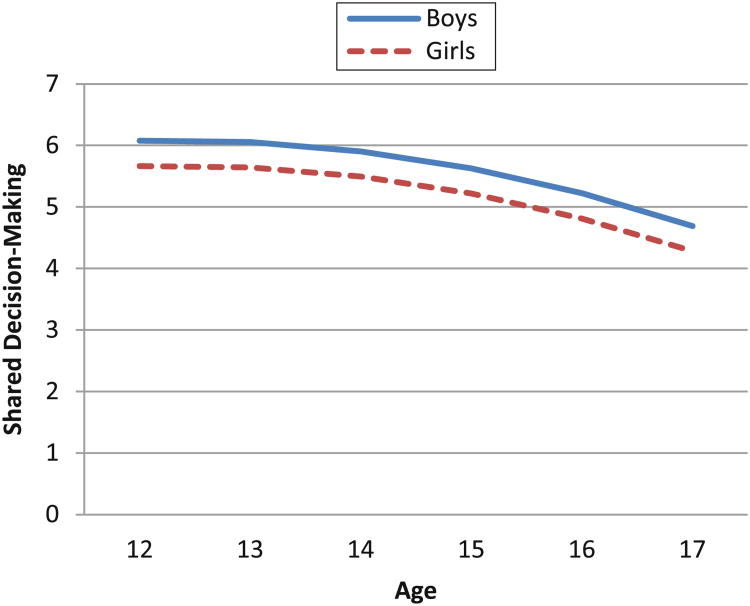

In the case of parents shared decision-making, the analysis revealed a significant effect of gender, γ = .41, SE = .21, p < .05, such that parents of boys shared more decisions than parents of girls (see means in Table 1). A significant quadratic pattern of change emerged, γ = −.06, SE = .02, p < .01, suggesting that parents' shared decision-making was relatively stable in early adolescence, declined slightly by age 16, and declined more steeply between ages 16 and 17 (Fig. 1). For both boys and girls, parents changed the most in the domain of homework (went from more shared decisions to fewer shared decisions). In line with prior work on family time (Crouter et al. 2004), there was significant linear decrease in parents' joint involvement with youth, γ = −23.04, SE = 3.42, p < .01, but joint involvement did not differ by youth gender.

Fig. 1.

Trajectory of parents' shared-decision making as a function of adolescent age. Intercept for boys versus girls is significantly different, p < .01; slopes are not significantly different by gender

These analyses also revealed that boys reported more risky behavior than girls overall, γ = 2.99, SE = .71, p < .01, and there was a significant linear increase in risky behavior across the 6 years of study, γ = 1.36, SE = .08, p < .01. In the case of depressive symptoms, a linear increase, γ = 1.10, SE = .18, p < .01, was qualified by an interaction with gender, γ = −.61, SE = .26, p < .01, and follow-ups revealed a more rapid increase in symptoms for girls, γ = 1.10, SE = .19, p < .01, than for boys, γ = .49, SE = .17, p < .01.

Bidirectional Associations Between Coparenting Dimensions and Adolescent Adjustment

We used cross-lagged structural equation models to address our second goal of testing the associations between coparenting and adolescent adjustment. Using the AMOS 18 statistical package (Arbuckle and Wothke 1999), we estimated four separate structural equation models with cross-lagged associations between each coparenting dimension and each measure of adolescent adjustment, using full information maximum likelihood (FIML) to estimate missing data (Enders and Bandalos 2001). To control for stability in each construct over time, we included paths from earlier scores to later scores (e.g., coparenting at Time 3 was regressed on coparenting at Time 2, etc.). Including these cross-lagged pathways allowed us to determine whether dimensions of coparenting and adjustment were associated with each other across time, independent of their stability and any cross-lagged contributions of the other variables. The residuals for coparenting dimensions and adjustment also were correlated within each time point (e.g., residual for coparenting at Time 2 was correlated with the residual for adjustment at Time 2, etc.). This step accounted for the time-specific association between coparenting and adjustment, independent of the association between the same two variables at the previous time point.

We tested adolescent gender differences in each of the four models using a series of multi-group analyses. We compared four models: (a) unconstrained (all parameters were allowed to vary across boys and girls), (b) measurement weights (only measurement weights were constrained as equal for boys and girls), (c) structural weights (measurement weights and intercepts and structural weights were constrained to be equal for boys and girls), and (d) structural residuals (paths were fully constrained to be equal for boys and girls). Instead of focusing on statistical differences in structural weights, we examined whether the unconstrained model was a better fit than a constrained model based on Chi squared (χ2)/degree of freedom differences between two models. In cases where unconstrained models yielded a better fit, t-ratios were examined to determine which paths differed significantly for boys and girls. We tested each model controlling for parent education. Models with and without education yielded the same pattern of results, however, and so education was not included in final models.

Model fit was assessed using three indices: (1) χ2, with high levels indicative of poor fit; (2) the comparative fit index (CFI; Bentler 1990), which assesses model fit in relation to an uncorrelated model; and (3) root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA; Steiger 1990), which assesses model fit, accounting for complexity. A χ2 value that is non-significant, a CFI above .95, and an RMSEA below .05, indicate good model fit (Kline 2005; MacCallum et al. 1996). Adequate model fit is indicated by a CFI between .90 and .95 or an RMSEA between .05 and .08 (Bentler 1990).

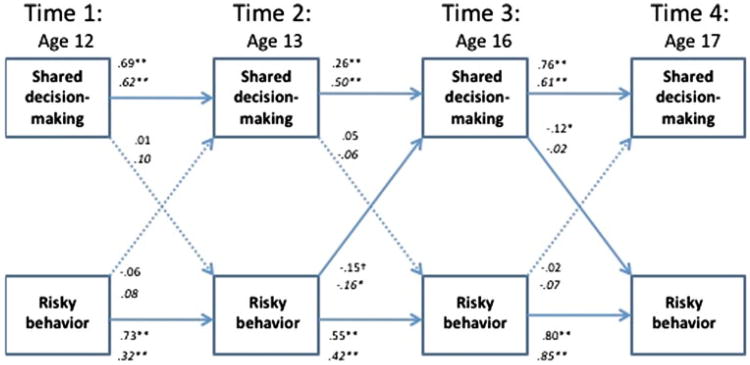

Shared Decision-Making

Model 1 tested the cross-lagged associations between parents' shared decision-making and adolescent risky behaviors. Nested model comparisons revealed that the unconstrained model provided the best fit (details available from the first author). Model fit for the unconstrained model was adequate, χ2(64) = 54.48, p = .00; CFI = .96; RMSEA = .07. Shared decision-making and risky behavior were stable across time for boys and girls. As shown in Fig. 2, girls' risky behavior at age 13 was a significant negative predictor of parents' shared decision-making at age 16, and boys' risky behaviors at 13 were marginally predictive of parents' shared decisions at age 16. However, according to the t ratios test of critical differences, this effect was not significantly different for boys versus girls, t = 1.25, ns. For boys but not girls (t = 2.08, p < .05), shared decision-making at age 16 was a significant negative predictor of risky behavior at age 17, suggesting that coparenting protected against further increases in boys' externalizing.

Fig. 2.

Cross-lagged SEM for parents' shared decision-making and adolescent risky behaviors. All effects are reported as standardized regression coefficients. Italicized effects are for girls. *p < .05; **p < .01; †p < .10

Model 2 tested the cross-lagged associations between parents' shared decision-making and adolescents' depressive symptoms. The measurement weights model provided the best fit for the data, meaning that only measurement weights were constrained to be equal for boys and girls (intercepts and residuals were free to vary). Model fit for the measurement weights model was generally good, χ2(52) = 63.15; p = .03, CFI = .95; RMSEA = .05. Shared decision-making and depressive symptoms were stable across time; however, there were no significant cross-lagged paths (results available from the first author).

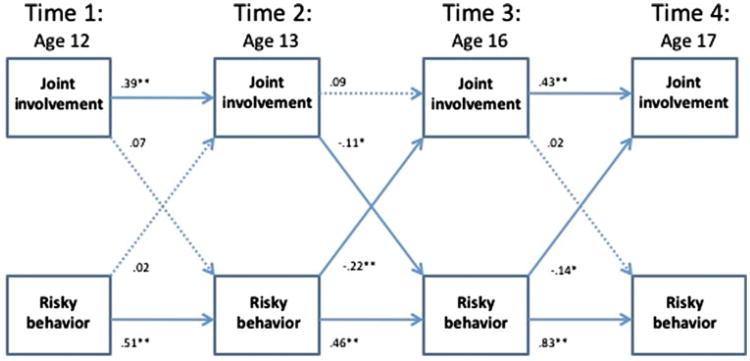

Joint Involvement

Model 3 tested cross-lagged associations between mother-father joint involvement and adolescent risky behavior. The measurements weights model, where measurement weights for boys and girls were constrained to be equal, was the best fitting model. Fit for this model was generally good, χ2(52) = 60.82, p = .02; CFI = .96; RMSEA = .02. Joint involvement and risky behavior were stable over time. As shown in Fig. 3, joint involvement at age 13 was related negatively to adolescents' risky behavior at age 16, suggesting that shared time with parents may protect against increased risky behavior. Risky behavior at age 13 also predicted less joint involvement at age 16. In turn, risky behavior at age 16 was a significant negative predictor of joint involvement at age 17, suggesting that behavior problems may affect negatively this type of coparenting.

Fig. 3.

Cross-lagged SEM for joint involvement and adolescent risky behaviors. All effects are reported as standardized regression coefficients. Effects are for girls and boys. *p < .05; **p < .01; †p < .10

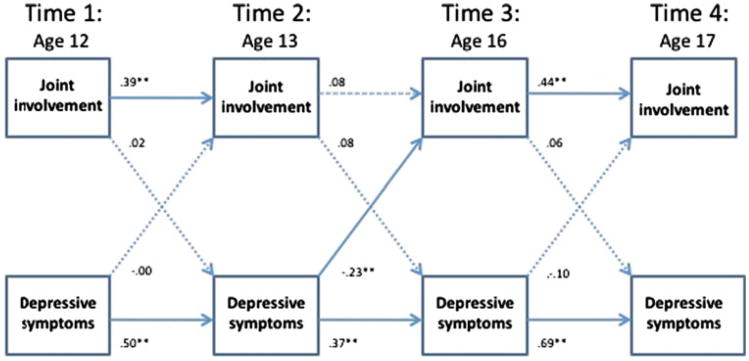

In model 4 we examined cross-lagged paths between joint involvement and adolescent depressive symptoms. The measurement weights model provided a significantly better fit compared to the other models, meaning that measurement weights were constrained for boys and girls. Fit for this model was acceptable, χ2(52) = 70.13, p = .01; CFI = .91; RMSEA = .07. Joint involvement and depressive symptoms were stable over time. As shown in Fig. 4, depressive symptoms at age 13 negatively predicted joint involvement at age 16, suggesting that adolescents' internalizing problems interfered with this form of coparenting. There were no significant pathways for the other direction of effect; that is, joint involvement did not predict adolescent depressive symptoms.

Fig. 4.

Cross-lagged SEM for joint involvement and adolescent depressive symptoms. All effects are reported as standardized regression coefficients. Effects are for boys and girls. *p < .05; **p < .01; †p < .10

Discussion

A growing literature has established that coparenting is a fundamental family systems dynamic, with implications for infant and early childhood adjustment. Drawing on longitudinal data from families with adolescents, findings from this study are consistent with past work and suggest that coparenting, as measured by shared parental decision-making and parents' joint involvement with their adolescent, are linked in bidirectional ways with adolescents' risky behaviors and depressive symptoms. This study adds to the literature by examining dimensions of coparenting that, we argued, are relevant to adolescent development, by testing the implications of youth adjustment for coparenting using a longitudinal design, and by examining the role of youth gender in these processes. Below, we review the findings, highlighting the ways in which this study advances understanding of coparenting during adolescence and of family systems dynamics, more generally.

Coparenting in Families of Adolescents

Our conceptualization of coparenting is rooted in a family systems perspective wherein family dynamics are understood as changing as a function of developmental changes experienced by family members. We focused on adolescence as a time of dramatic change, when parents and youth renegotiate their relationships around youth's increasing autonomy and focus on the world beyond the home. This study extended prior research on coparenting—which has targeted infants and young children and is largely based on self-reported measures—to examine coparenting processes in adolescence, as reported by multiple family members. We also moved beyond prior research on coparenting conflicts in adolescence to study facets of coordinated parenting that likely would be susceptible to renegotiation during a period of increasing youth autonomy.

In spite of youth's developing independence, parents in this sample generally shared decision-making responsibility; this was particularly the case for parents of sons, who, across the study period, shared approximately 70 % of the decisions in which either parent was involved. There was a quadratic pattern of change in parents' shared decision-making, such that shared decision-making was relatively stable between ages 12 and 13, declined slightly by age 16, and declined more steeply between ages 16 and 17. This is not surprising given normative changes in adolescent development, wherein adolescents start making more decisions on their own. However, it is notable that by age 17, parents shared decisions in more than half of the eight domains measured.

With respect to joint involvement, mothers, fathers, and adolescents spent about 6 h/week, on average, in shared activities when youth were 12 years old. Shared involvement by both parents and offspring decreased significantly, averaging about 4 h/week by the time youth were 17 years of age. This pattern reflects normative developmental trends in how adolescents spend their time as established in prior research on family time (Crouter et al. 2004). Taken together, the results suggest that these domains of coparenting were relevant to families of adolescents. Future research should examine how coparents of adolescents navigate new challenges in other childrearing domains, such as parental monitoring and knowledge.

Bidirectional Links Between Coparenting and Adolescent Adjustment

In agreement with the family systems notion that family dynamics are bidirectional, and in line with research with young children, we found that shared decision-making protected against normative increases in boys' risky behavior, and joint involvement protected against boys' and girls' risky behaviors and depressive symptoms, even in this non-clinical sample of families in which adolescents reported low levels of problems. In turn, we found evidence for youth's effects on their parents, including that boys' and girls' behavior problems had implications for parents' shared decision-making, and that boys' and girls' risky behaviors and depressive symptoms negatively predicted parents' joint involvement. By controlling for associations at prior time points, we confirmed that the bidirectional links between coparenting and adolescent adjustment were specific to particular points in youth's adolescence. Although studies with younger children have found little evidence that child gender plays a role in coparenting (e.g., Stright and Bales 2004), our findings provided initial evidence that the links between coparenting and adolescent adjustment may differ for girls and boys. Below, we discuss these effects in detail.

Consistent with our expectation that adolescent adjustment would be enhanced when parents exhibit positive coparenting, we found that, for boys, parents' shared-decision-making at age 16 was related to fewer risky behaviors at age 17. Whereas this prediction was supported for boys, parents' shared decision making did not protect against risky behaviors for girls. One reason for this gender difference may be that parents expected boys to engage in more risky behaviors than girls, and in anticipation, took a more active role in coordinating their decisions about their sons. This interpretation is consistent with our finding that, on average, parents of sons shared more decisions than parents with daughters. Also in line with previous research (e.g., Zahn-Waxler 1993), girls engaged in significantly fewer risky behaviors than boys: Parents' shared decision-making may only become protective once the level of risky behaviors reaches a certain threshold. These results also are consistent with the idea that inter-parental dynamics have stronger implications for boys' adjustment (Margolin et al. 2001; McHale 1995). Our findings add to prior research that has focused on negative marital dynamics in showing that boys may be influenced more strongly by positive coparent interactions, specifically decision-making.

With respect to the implications of adolescent adjustment for shared decision-making, youth risky behavior at age 13 was related negatively to parents' shared decisions at age 16, and these associations were similar for boys and girls. Prior research suggests that parents of youth who experience more behavior problems have a tendency to withdraw from parenting responsibilities, including support and monitoring (Kerr and Stattin 2003). Taking a step beyond individual parenting practices, results from this study provide initial evidence that behavior problems undermine coparenting.

In contrast to the findings for risky behaviors, there were no significant links between shared decision-making and depressive symptoms. Some prior research found that coparenting conflict was related to adolescent externalizing but not internalizing behaviors (Baril et al. 2007; Feinberg et al. 2007), and our results pertaining to positive shared decision-making were consistent with this pattern. Feinberg et al. (2007) suggested that depressive symptoms are less visible to parents than risky behaviors, and that parents are more motivated to work together on adjustment problems that are readily apparent.

In contrast to the lack of association between shared decision making and internalizing problems, parents' joint involvement was linked to both depressive symptoms and risky behavior. Consistent with our prediction based on past research on the positive correlates of parent-offspring shared time, coparents' joint involvement at age 13 protected against normative increases in youth's risky behaviors at age 16. And, there was evidence that associations between joint involvement and risky behavior were bidirectional in that youth's risky behavior at age 13 was related to less joint involvement at age 16. In turn, youth who reported more risky behaviors at age 16 spent less time together with parents at age 17 suggesting that youth behavior problems disrupted this dimension of coparenting, beyond normative declines in joint involvement with adolescents. These findings are consistent with research on coparenting during the preschool years, which documents an inverse association between family harmony and child behavior problems (McHale and Rasmussen 1998). In light of research documenting the effect of adolescent externalizing problems on inter-parental conflict (Cui et al. 2007), it is possible that coparent conflict surrounding offsprings' behavior problems undermined parents' ability to work together, which is reflected in less joint involvement. Missing years of data collection may have reduced stability within constructs and allowed the detection of correlations between adolescent adjustment and coparenting only at certain time points. Future research should examine bidirectional links between these constructs over consecutive years of adolescence to better understand the timing of associations.

Also in support of our expectation that adolescent adjustment problems would interfere negatively with coparenting, youth depressive symptoms at age 13 were associated with less joint involvement at age 16. In line with evidence that adolescents with internalizing problems view their parents as less accepting (e.g., Garber et al. 1997) and their families as less cohesive (e.g., Stark et al. 1990), it is possible that youth with depressive symptoms withdraw from interactions with their parents. Our findings are consistent with those of McConnell and Kerig (2002) who documented significant correlations between youth internalizing but not externalizing problems, and mother-father differences in parental investment. In sum, the results suggest that associations with joint involvement and adjustment were similar for boys and girls and that both externalizing and internalizing problems had negative implications for mother–father–offspring involvement. Together, these findings indicate that adolescent internalizing and externalizing may have different implications for coparenting, lending further support to a need for research coparenting by parents of adolescents.

Conclusions

This study is among the first to examine how coparenting unfolds across the course of adolescence and how it is linked longitudinally to youth adjustment. As have prior investigators, we argued that a conceptualization of coparenting in adolescence should include elements of parenting that may emerge and/or are central during this developmental period. A corollary to this argument is that, like other family systems processes, coparenting dynamics are not solely parent-driven but also are shaped by adolescents. The dimensions of coparenting we studied here were predicted by youth's internalizing and externalizing behaviors, and furthermore, youth gender played a role in coparenting-adjustment linkages.

In the face of its contributions, there were also several limitations to this study. First, our design was correlational, and although we were able to illuminate directions of effect, inferences about causality cannot be drawn. Interventions that promote coparenting practices using experimental designs for their evaluation constitute an important research direction. Second, our sample was small for this type of analysis, possibly masking some significant effects, and it was comprised of two-parent European American families from a circumscribed geographical location, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Further research is needed to test the significance of coparenting in other ethnic groups, and families that include stepparents or non-marital coparenting partners. In addition, while significant, many effects were small. With respect to the research design, although our study included four waves of data collected over 6 years, due to the timing of data collection, ages 14and 15 are not reflected in these analyses. On the one hand, consideration of these middle adolescent years might help to better explain some associations. Given that the majority of significant cross lagged associations were evident between ages 13 and 16, however, it also is possible that this feature of our design allowed for a degree of inter-individual change to occur so that coparenting-adjustment associations were evident beyond the effects of stability in each. Finally, with respect to the measures of coparenting, as in some prior research (McHale and Rasmussen 1998), parents' joint involvement was used as an index of coparenting, however, the qualities of the interactions and activities that took place during their shared time were not measured. Observational measures of coparenting have been used with families of younger children and this is an important direction for coparenting research on adolescents.

Although our study requires replication and extension, findings from this research advance the understanding of the mutual influences between coparenting, a key family systems dynamic, and adolescent adjustment. This work makes an important contribution to the coparenting literature, which largely has overlooked the new challenges that parents face during their offsprings' adolescent years. It also adds to the literature on adolescent development, which, to date, has paid little attention to the role of coparenting in adolescents' well-being. Finally, our work advances the family systems literature by going beyond a focus on dyadic relationships and parent-driven socialization processes. Taken together, our findings also highlight the utility of studying family dynamics during times of developmental transitions.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the graduate and undergraduate assistants, staff, and faculty collaborators for their help in conducting this study, as well as the participating families for their time and insights about youth development. This work was funded by a Grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01-HD32336) to Ann C. Crouter and Susan M. McHale, Co-Principal Investigators.

Biographies

Elizabeth M. Riina is a Postdoctoral Research Scientist at the National Center for Children and Families, at Teachers College, Columbia University. She received her doctorate in Human Development and Family Studies from Penn State University. Her research interests include family dynamics during adolescence, and the connections between families and their broader ecological contexts.

Susan M. McHale is a Professor of Human Development and the Director of the Social Science Research Institute at The Pennsylvania State University. She received her Ph.D. in Developmental Psychology from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her research interests include family relationships and dynamics, youth adjustment and development, and the roles of gender and culture in these phenomena.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: This article was part of E.R.'s doctoral dissertation. E.R. conceived of this study, conducted analyses, interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript: S.M. participated in study design, interpretation of the data, and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth M. Riina, Email: riina@tc.columbia.edu, National Center for Children and Families, Teachers College, Columbia University, 525 West 120th Street, Box 39, New York, NY 10027, USA.

Susan M. McHale, Email: x2u@psu.edu, The Pennsylvania State University, 601 Oswald Tower, University Park, PA 16802, USA.

References

- Angold A, Rutter M. Effects of age and pubertal status on depression in a large clinical sample. Development and Psycho-pathology. 1992;4:5–28. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL, Wothke W. Amos 4.0 user's guide. Chicago: Small Waters Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Baril ME, Crouter AC, McHale SM. Processes linking adolescent well-being, marital love, and coparenting. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:645–654. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes GM, Hoffman JH, Welte JW, Farrell MP, Dintcheff BA. Adolescents' time use: Effects on substance use, delinquency, and sexual activity. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2007;36:697–710. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumpus MF, Crouter AC, McHale SM. Parental autonomy granting during adolescence: Exploring gender differences in context. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:163–173. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.37.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Gleason T, Sesma A. Internalization, autonomy, and relationships: Development during adolescence. In: Grusec JE, Kuczynski L, editors. Parenting and children's internalization of values: A handbook of contemporary theory. New York: Wiley; 1997. pp. 78–99. [Google Scholar]

- Crouter AC, Head MR, McHale SM, Tucker CJ. Family time and the psychosocial adjustment of adolescent siblings and their parents. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:147–162. [Google Scholar]

- Cui M, Donnellan MB, Conger RD. Reciprocal influences between parents' marital problems and adolescent internalizing and externalizing behavior. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:143–159. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dornbusch SM, Carlsmith JM, Bushwall SJ, Ritter PL, Leiderman H, Hastorf H, et al. Single parents, extended households, and the control of adolescents. Child Development. 1985;56:326–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles J, Barber B. The risky behavior scale. The University of Michigan; 1990. Unpublished measure. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Bandalos DL. The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling. 2001;8:430–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg ME. Coparenting and the transition to parenthood: A framework for prevention. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2002;5:173–195. doi: 10.1023/a:1019695015110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg ME, Kan ML, Hetherington EM. The longitudinal influence of coparenting conflict on parental negativity and adolescent maladjustment. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69:687–702. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00400.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd FJ, Zmich DE. Marriage and the parenting partnership: Perceptions and interactions of parents with mentally retarded and typically developing children. Child Development. 1991;62:1434–1448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber J, Robinson NS, Valentiner D. The relation between parenting and adolescent depression: Self-worth as a mediator. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1997;12:12–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hill JP, Lynch ME. The intensification of gender-related role expectations during early adolescence. In: Brooks-Gunn J, Petersen AC, editors. Girls at puberty: Biological and psychosocial perspectives. New York: Plenum; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Kerig PK, Cowan PA, Cowan CP. Marital quality and gender differences in parent–child interaction. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:931–939. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr M, Stattin H. Parenting of adolescents: Action or reaction? In: Crouter AC, Booth A, editors. Children's influence on family dynamics: The neglected side of family relationships. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2003. pp. 121–151. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practices of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. The children's depression inventory (CDI) Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1985;21:995–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird RD, Pettit GS, Bates JE, Dodge KA. Parents' monitoring relevant knowledge and adolescents' delinquent behavior: Evidence of correlated developmental changes and reciprocal influences. Child Development. 2003;74:752–768. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson RW, Richards MH, Moneta G, Holmbeck G, Duckett E. Changes in adolescents' daily interactions with their families from ages 10 to 18: Disengagement and transformation. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:744–754. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey EW, Caldera Y, Colwell M. Correlates of coparenting during infancy. Family Relations. 2005;54:346–359. [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Browne MW, Sugawara HM. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods. 1996;1:130–149. [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G, Gordis EB, John RS. Coparenting: A link between marital conflict and parenting in two-parent families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:3–21. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell MC, Kerig PK. Assessing coparenting in families of school-age children: Validation of the coparenting and family rating system. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science. 2002;34:44–58. [Google Scholar]

- McHale JP. Coparenting and triadic interactions during infancy: The roles of marital distress and child gender. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:985–996. [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Crouter AC, Tucker CJ. Free-time activities in middle childhood: Links with adjustment in early adolescence. Child Development. 2001;72:1764–1778. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale JP, Kazali C, Rotman T, Talbot J, Carleton M, Lieberman R. The transition to coparenthood: Parents' prebirth expectations and early coparental adjustment at 3 months postpartum. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:711–733. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404004742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale JP, Rasmussen JL. Coparental and family group-level dynamics during infancy: Early family precursors of child and family functioning during preschool. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:39–59. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minuchin P. Families and individual development: Provocations from the field of family therapy. Child Development. 1985;56:289–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoppe SJ, Mangelsdorf SC, Frosch CA. Coparenting, family process, and family structure: Implications for preschoolers' externalizing behavior problems. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:526–545. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.3.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan L, McHale SM, Crouter AC, Osgood DW. Warmth with mothers and fathers from middle childhood to late adolescence: Within- and between-families comparisons. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:551–563. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.3.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, Campoine-Barr N, Daddis C. Longitudinal development of family decision-making: Defining healthy behavioral autonomy for middle-class African American adolescents. Child Development. 2004;75:1418–1434. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark KD, Humphrey LL, Crook K, Lewis K. Perceived family environments of depressed and anxious children: Child's and maternal figure's perspectives. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1990;18:527–547. doi: 10.1007/BF00911106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiger JH. Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1990;25:173–180. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. We know some things: Parent–adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Stright AD, Bales SS. Coparenting quality: Contributions of child and parent characteristics. Family Relations. 2004;52:232–240. [Google Scholar]

- Van Egeren LA. The development of the coparenting relationship over the transition to parenthood. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2004;25:453–477. [Google Scholar]

- Youniss J, Smollar J. Adolescent relations with mothers, fathers, and friends. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Zahn-Waxler C. Warriors and worriers: Gender and psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 1993;5:79–89. [Google Scholar]