Abstract

Background

Recent findings suggest that alcohol consumption may reduce risk of multiple myeloma (MM).

Methods

To better understand this relationship, we conducted an analysis of six case-control studies participating in the International Multiple Myeloma Consortium (1,567 cases, 7,296 controls). Summary odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) relating different measures of alcohol consumption and MM risk were computed by unconditional logistic regression with adjustment for age, race, and study center.

Results

Cases were significantly less likely than controls to report ever drinking alcohol (men: OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.59-0.89, women: OR 0.81, 0.68-0.95). The inverse association with MM was stronger when comparing current to never drinkers (men: OR=0.57, 95% CI 0.45-0.72, women: OR=0.55, 95% CI 0.45-0.68), but null among former drinkers. We did not observe an exposure-response relationship with increasing alcohol frequency, duration or cumulative lifetime consumption. Additional adjustment for body mass index, education, or smoking did not affect our results; and the patterns of association were similar for each type of alcohol beverage examined.

Conclusions

Our study is, to our knowledge, the largest of its kind to date, and our findings suggest that alcohol consumption may be associated with reduced risk of MM.

Impact

Prospective studies, especially those conducted as pooled analyses with large sample sizes, are needed to confirm our findings and further explore whether alcohol consumption provides true biologic protection against this rare, highly fatal malignancy.

INTRODUCTION

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a rare B-cell malignancy characterized by abnormal monoclonal plasma cells in the bone marrow, monoclonal immunoglobulin in serum and/or urine, lytic bone lesions, and in some patients, end-organ damage. MM is highly fatal, with a five-year survival rate of less than 30%.1 In the United States, MM is responsible for one-third of all lymphoma-related deaths, despite accounting for only one-fifth of diagnosed lymphoid malignancies.1

The etiology of MM is poorly understood. Established risk factors include older age, male sex, African ancestry, and obesity.2 Findings suggestive of a protective effect of alcohol consumption on MM risk are less consistent, as demonstrated in some case-control studies3-6 and cohort investigations,7-10 but not others.11-14 Given the rarity of MM many of these past investigations had limited statistical power to detect an alcohol effect of moderate size. To better understand the relationship between alcohol consumption and MM, we conducted a pooled analysis of data from six case-control studies participating in the International Multiple Myeloma Consortium (IMMC).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Population

For this analysis, we pooled individual-level questionnaire data from the six case-control studies in the IMMC that had collected information on alcohol consumption (1,567 cases, 7,296 controls). Methods of previously published studies have been described.1,4,5,15,16 Enrollment period, age eligibility, study design (source of controls: hospital, population), number of cases and controls, and the centers within each study are summarized in Table 1. The European EpiLymph collaboration included studies that used both population and hospital-based controls, and Utah included spouse and population controls which we considered as population controls for our analysis. Four of the studies were conducted in North America and the remaining in Europe. Participants with histologically confirmed incident primary diagnoses of MM (ICD-O-3 diagnostic codes of 9731.3, 9732.3, 9734.3, ICD-9 of 203, and the equivalent) that occurred during the respective enrollment periods were eligible for inclusion in this analysis. However, one study, Utah, enrolled both prevalent and incident cases of MM identified at a major regional myeloma clinic. In our sensitivity analysis we examined associations for incident and prevalent cases separately, and found the associations were not measurably different, therefore we included both types of cases in this analysis. The original data for each study were collected in-person by trained interviewers or by self-administered questionnaire. Protocols for the participating case-control studies were approved by the respective local institutional review boards, and study participants provided written informed consent.

Table 1. International Multiple Myeloma Consortium (IMMC) Lifestyle Factors Pooling Project (LFPP): studies with alcohol data.

| Case-control studies | Enrollment Period | Age Eligibility (years) | Study Design5 |

Cases | Controls | % Caucasian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Italy 1 | 1991-1993 | 20-74 | Population | 270 | 1,161 | 100 |

| NCI-Connecticut | 1996-2000 | 21-84 | Population | 183 | 716 | 91 |

| NCI Population Health Study 2 | 1986-1989 | 30-79 | Population | 573 | 2,131 | 57 |

| Salt Lake City, Utah | 2008-present | ≥18 | Population | 119 | 247 | 98 |

| EpiLymph 3 | 1998-2004 | ≥17 | Population | 92 | 1,046 | 97 |

| EpiLymph 4 | 1998-2004 | ≥17 | Hospital | 186 | 1,419 | 96 |

| Roswell Park Cancer Institute (RPCI), Buffalo, NY | 1982-1998 | ≥20 | Hospital | 144 | 576 | 100 |

Italy: Firenze, Forli, Imperia, Latina, Ragusa, Siena, Torin

NCI Population Health Study: Atlanta, GA, Detroit, MI, NJ

EpiLymph: Italy, Germany (Ludwigshafen/Upper Palatinate, Heidelberg/Rhine-Neckar County, Wurzburg/Lower Frankonia, Hamburg, Bielefeld and Munich)

EpiLymph: Czech Republic, Ireland, France (Amiens, Fijon, Monepellier), Spain (Barcelona, Tortosa, Reus, Madrid)

Based on source of controls. Utah also included spouse controls.

Alcohol Data

For this pooled analysis we requested data from each participating study, including variables on alcohol consumption, case/control status, and various demographic and lifestyle factors. We examined several measures of alcohol consumption, including usual alcohol drinking status (never, ever), former or current drinker, frequency (drinks per week), duration (years) and cumulative intake (drinks in lifetime). Alcohol drinking status was based on question(s) about their usual drinking behaviors prior to any current illness. Among ever drinkers, former/current status was calculated from questions regarding duration of drinking, therefore, we were unable to determine former/current status for subjects who did not provide drinking duration (229 cases, 1140 controls). In our sensitivity analysis we examined the associations between ever drinking and MM for subjects with and without current/former drinking status, and found the associations were not measurably different. We also examined associations for former drinkers excluding participants recently quit (i.e., ceased drinking within two years prior to completion of the questionnaire), as well as current drinkers including the participants who recently quit.

We defined alcohol drinking duration as the total number of years beverage-specific (beer, wine, liquor) or total alcohol was consumed. When not directly provided we calculated beverage-specific consumption frequencies (the average number of standard drinks per week) within each study by multiplying the reported number of beverage-specific drinks per week by the estimated volume per serving in North America (350mL beer, 120mL wine, 45ml liquor) or Europe (250mL beer, 100mL wine, 35mL liquor).17 This product was multiplied by the estimated ethanol content of each beverage (beer 5%, wine 12%, liquor 40%), and then divided by the reported average volume of ethanol per serving across the three beverage types, 15.6ml.17 The consumption frequency for total alcohol was calculated by dividing cumulative intake by duration for total alcohol. Beverage-specific estimates of cumulative intake were calculated by multiplying the duration and consumption frequencies for each beverage type. The cumulative intake of total alcohol was calculated as the sum of beverage-specific cumulative intakes. Alcohol sources beyond beer, wine, and liquor, if provided, were minimal and not included in any harmonized alcohol variables.

Statistical Analysis

Data were checked for internal consistency, outliers, and missing values prior to pooling across studies. In a sensitivity analysis, we assessed the impact of excluding subjects with values above the 95th percentile for alcohol frequency, duration and cumulative intake, and found that it did not measurably impact risk estimates. Therefore, we decided not to drop outliers. We found no evidence of outliers for the non-drinking covariates. Missing data for both the alcohol drinking variables and other covariates were retained in the models, since we found that dropping missing data did not impact our results.

Due to differences in alcohol drinking by sex, we categorized the quantitative alcohol variables using sex-specific cut points based on the tertiles among the pooled controls: frequency (men: <8.7, ≤21.4, >21.4, women: <1.6, ≤7.1, >7.1 drinks per week); duration (men: <30, ≤43, >43, women: <23, ≤40, >40 years); cumulative intake (men: 16.882, ≤48,400, >48,400, women: <2,743, ≤12,600, >12,600 drinks). These cut points were also used to categorize beverage-specific consumption measures.

All analyses were performed using SAS unless otherwise specified. Within each study, we computed sex-specific odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) relating the aforementioned alcohol variable categories to MM risk through unconditional logistic regression, with adjustment for age group (<50, 50-59, 60-69, 70+ years), race (white, black, other), and study center. Tests of trend for alcohol frequency, duration, and cumulative intake were performed by linear regression analysis. We used the R package MiMa18 to conduct a meta-analysis of study-specific findings using both random and fixed effects models. Heterogeneity between studies in the meta-analysis was assessed using the Q statistic.

We also conducted a pooled analysis in a single harmonized data set, with ORs and 95% CIs for alcohol measures computed using unconditional logistic regression with adjustment for age, race, and study center. We evaluated potential confounding in analyses additionally adjusted for education level (<12 years of study; 12+ years or high school graduate; some attendance at college, technical, or vocational school after high school; graduation from college without further studies; or, other), body mass index (BMI; <18.5, <25, <30, <35, 35+ kg/m2), and smoking status (ever, never). To assess effect modification of alcohol-MM associations, we investigated associations of alcohol consumption across strata of study design, smoking status, and BMI using the likelihood ratio test.

RESULTS

In the pooled study population approximately 45% of cases and 50% of controls were male; close to 85% of cases and controls were white (Supplemental Table 1). Distributions of other covariables differed slightly but not dramatically between pooled cases and controls.

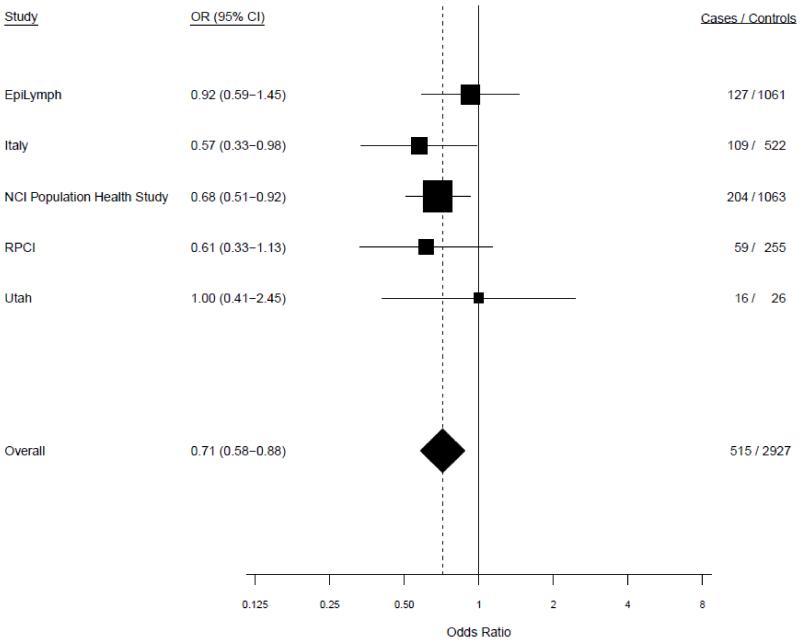

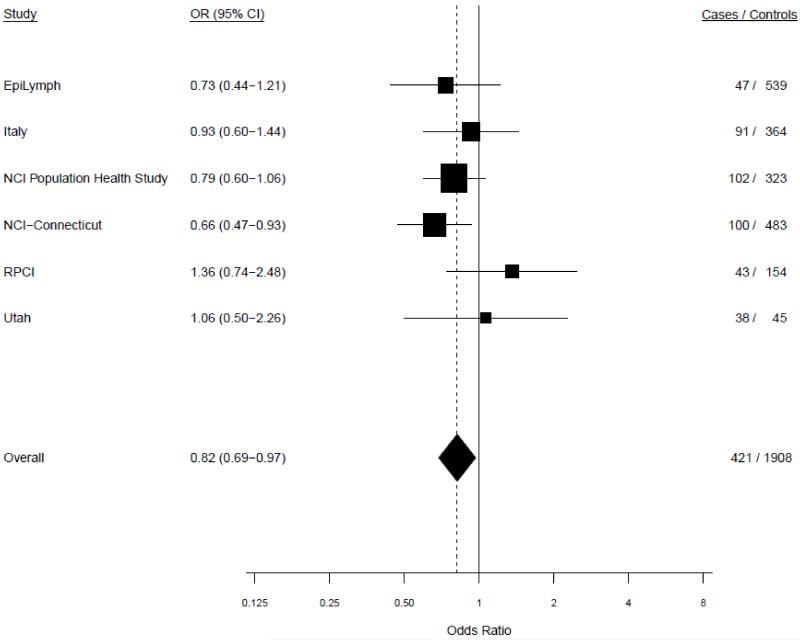

Age-adjusted study-specific associations for ever versus never drinking alcohol were fairly homogeneous in both random and fixed effects models. In the random effects models, tests of heterogeneity between studies did not achieve statistical significance among men (P=0.61) or women (P=0.40) (Figure 1). Since the results from the meta-analysis and pooled analysis were virtually identical we present results from the pooled analysis, unless otherwise specified.

Figure 1.

a. Study-specific risks of multiple myeloma for ever versus never drinking alcohol among males. P-heterogeneity=0.61.

b. Study-specific risks of multiple myeloma for ever versus never drinking alcohol among females. P-heterogeneity=0.40.

In the pooled analysis of ever vs. never consumption of alcohol, ever consumption was associated with a decreased risk of MM for men (OR=0.72, 95% CI 0.59-0.89) and women (OR=0.81, 95% CI 0.68-0.95) (Table 2). The inverse association was stronger for current drinkers (men: OR=0.57, 95% CI 0.44-0.72; women OR=0.55, 95% CI 0.45-0.68), as well as for current drinkers combined with participants who recently quit (i.e., ceased drinking within two years prior to questionnaire). The risks for former drinkers compared to never drinkers were elevated, however, after excluding those who recently quit, the associations were null. Among current drinkers, including those who recently quit, there was no evidence of a monotonic trend of MM risk with increasing alcohol drinking frequency, duration, or cumulative intake for either men or women, even though some p-trend values were statistically significant when compared to never drinkers (Table 2). Similar patterns of association were seen among ever and former drinkers (excluding those who recently quit) (Supplemental Table 2). These associations did not change with additional adjustment for education, smoking status, or BMI (data not shown).

Table 2. Risk of Multiple Myeloma associated with alcohol consumption in pooled study population by gender.

| Alcohol Consumption | Male |

Female |

p- interaction |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Control | OR1, 2 | 95% CI1, 2 | OR1, 3 | 95% CI1, 3 | Case | Control | OR1, 2 | 95% CI1, 2 | OR1, 3 | 95% CI1, 3 | ||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Total | 699 | 3674 | - | - | - | - | 856 | 3541 | - | - | - | - | |

| Never Drinker | 184 | 747 | 1.00 | - | - | - | 435 | 1633 | 1.00 | - | - | - | |

| Ever Drinker | 515 | 2927 | 0.72 | 0.59-0.89 | - | - | 421 | 1908 | 0.81 | 0.68-0.95 | - | - | 0.59 |

| Current | 257 | 1803 | 0.57 | 0.45-0.72 | - | - | 202 | 1179 | 0.55 | 0.45-0.68 | - | - | |

| Current4 | 289 | 1851 | 0.65 | 0.52-0.82 | - | - | 226 | 1199 | 0.62 | 0.51-0.77 | - | - | |

| Former | 126 | 449 | 1.11 | 0.84-1.47 | - | - | 122 | 264 | 1.32 | 1.02-1.70 | - | - | |

| Former5 | 94 | 401 | 0.90 | 0.66-1.24 | - | - | 98 | 244 | 1.11 | 0.85-1.47 | - | - | |

| Current4 Drinker Frequency6 | |||||||||||||

| T1 | 61 | 317 | 0.70 | 0.50-0.98 | 1.00 | - | 43 | 279 | 0.55 | 0.38-0.79 | 1.00 | - | |

| T2 | 54 | 412 | 0.49 | 0.34-0.70 | 0.74 | 0.48-1.12 | 67 | 296 | 0.62 | 0.45-0.85 | 1.01 | 0.64-1.59 | |

| T3 | 74 | 461 | 0.62 | 0.45-0.87 | 0.95 | 0.63-1.41 | 86 | 348 | 0.77 | 0.57-1.04 | 1.22 | 0.79-1.91 | 0.21 |

| p-trend | 0.01 | 0.90 | 0.23 | 0.36 | |||||||||

| Current4 Drinker Duration7 | |||||||||||||

| T1 | 63 | 571 | 0.64 | 0.45-0.92 | 1.00 | - | 37 | 359 | 0.51 | 0.34-0.75 | 1.00 | - | |

| T2 | 95 | 578 | 0.71 | 0.52-0.96 | 1.12 | 0.73-1.73 | 93 | 404 | 0.76 | 0.58-1.01 | 1.45 | 0.91-2.31 | |

| T3 | 122 | 645 | 0.61 | 0.46-0.81 | 0.98 | 0.61-1.58 | 95 | 426 | 0.57 | 0.43-0.75 | 0.99 | 0.59-1.65 | 0.27 |

| p-trend | 0.001 | 0.84 | 0.001 | 0.86 | |||||||||

| Current4 Drinker Cumulative8 | |||||||||||||

| T1 | 61 | 370 | 0.65 | 0.46-0.91 | 1.00 | - | 49 | 288 | 0.63 | 0.44-0.91 | 1.00 | - | |

| T2 | 59 | 403 | 0.56 | 0.40-0.80 | 0.90 | 0.60-1.36 | 59 | 317 | 0.56 | 0.41-0.78 | 0.79 | 0.51-1.23 | |

| T3 | 71 | 419 | 0.61 | 0.44-0.86 | 1.02 | 0.67-1.54 | 88 | 318 | 0.76 | 0.57-1.02 | 0.99 | 0.64-1.53 | 0.53 |

| p-trend | 0.01 | 0.87 | 0.16 | 0.79 | |||||||||

Adjusted for age, race and center

Reference group is never drinkers

Reference group is among drinkers

Includes participants who ceased drinking within two years prior to completion of questionnaire

Excludes participants who ceased drinking within two years prior to completion of questionnaire

Average number of standard drinks per week

Male tertiles: <8.7, ≤21.4, >21.4

Female tertiles: <1.6, ≤7.1, >7.1

Number of years consumed

Male tertiles: <30, ≤43, >43

Female tertiles: <23, ≤40, >40

Lifetime number of standard drinks (frequency × duration)

Male tertiles: <16,882, ≤48,400, >48,400

Female tertiles: <2,743, ≤12,600, >12,600

In the analysis that stratified by study design, the inverse association of ever alcohol drinking with MM was significant among population-based studies (OR=0.73, 95% CI 0.63-0.84), but not among hospital-based studies (OR=0.90, 95% CI 0.68-1.18) (Table 3). The interaction of ever vs. never alcohol drinking with study design was statistically significant (p =0.01). In contrast, the associations were not significantly different by smoking status or BMI. We also found consistent results among black participants (cases=231, controls=992).

Table 3. Risk of Multiple Myeloma associated with alcohol consumption in pooled study population by various factors.

| Case | Control | OR1, 2 | 95% CI1, 2 | Case | Control | OR1, 2 | 95% CI1, 2 | p-interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||

|

STUDY DESIGN

|

|||||||||

| Alcohol Status | Hospital | Population | |||||||

|

|

|

||||||||

| Never Drinker | 128 | 810 | 1.00 | - | 491 | 1570 | 1.00 | - | |

| Ever Drinker | 197 | 1148 | 0.90 | 0.68-1.18 | 739 | 3687 | 0.73 | 0.63-0.84 | 0.01 |

| Current | 79 | 637 | 0.76 | 0.54-1.07 | 380 | 2345 | 0.53 | 0.45-0.63 | |

| Current3 | 91 | 666 | 0.81 | 0.58-1.14 | 424 | 2384 | 0.60 | 0.51-0.71 | |

| Former | 31 | 166 | 1.04 | 0.66-1.64 | 217 | 547 | 1.21 | 0.99-1.48 | |

| Former4 | 19 | 156 | 0.79 | 0.45-1.37 | 173 | 508 | 1.02 | 0.82-1.27 | |

|

SMOKING STATUS

|

|||||||||

|

Ever Smoker

|

Never smoker

|

||||||||

| Never Drinker | 207 | 849 | 1.00 | - | 412 | 1528 | 1.00 | - | |

| Ever Drinker | 576 | 3223 | 0.74 | 0.61-0.89 | 356 | 1611 | 0.84 | 0.70-1.01 | 0.50 |

| Current | 278 | 2017 | 0.53 | 0.43-0.66 | 179 | 965 | 0.65 | 0.52-0.81 | |

| Current3 | 315 | 2070 | 0.61 | 0.49-0.76 | 197 | 980 | 0.71 | 0.57-0.88 | |

| Former | 161 | 512 | 1.16 | 0.90-1.50 | 86 | 201 | 1.34 | 1.00-1.80 | |

| Former4 | 124 | 459 | 0.95 | 0.72-1.26 | 68 | 186 | 1.10 | 0.80-1.51 | |

|

BMI

|

|||||||||

|

BMI <25 kg/m2

|

BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2

|

||||||||

| Never Drinker | 217 | 881 | 1.00 | - | 318 | 1149 | 1.00 | - | |

| Ever Drinker | 320 | 1382 | 0.79 | 0.64-0.98 | 392 | 2023 | 0.73 | 0.60-0.88 | 0.77 |

| Current | 143 | 1106 | 0.54 | 0.41-0.69 | 164 | 1014 | 0.57 | 0.45-0.72 | |

| Current3 | 169 | 1136 | 0.62 | 0.48-0.79 | 193 | 1051 | 0.66 | 0.52-0.83 | |

| Former | 109 | 309 | 1.38 | 1.03-1.84 | 134 | 380 | 1.10 | 0.86-1.42 | |

| Former4 | 83 | 279 | 1.11 | 0.80-1.52 | 105 | 343 | 0.94 | 0.71-1.24 | |

Adjusted for sex, age, race and center

Reference group is never drinkers

Includes participants who ceased drinking within two years prior to completion of questionnaire

Excludes participants who ceased drinking within two years prior to completion of questionnaire

Similar patterns of association were seen for each type of alcohol beverage (beer, wine, liquor) (Supplemental Table 3). We found reduced risks of MM among ever drinkers of beer, wine and liquor, but no meaningful dose-response associations.

DISCUSSION

In this pooled analysis of 1,567 cases and 7,296 controls, participants who ever drank alcohol had a lower risk of MM compared to those who never drank. This significant inverse association persisted for current drinkers, but not for former drinkers. We found no dose-response relationships with frequency, duration, or cumulative intake of alcohol. The alcohol-MM associations were similar by different types of alcoholic beverage.

An association between alcohol drinking and decreased risk of MM has also been observed in some cohort studies.7,10,19,20 The largest of these studies, an analysis within the Million Women cohort that included 1584 cases followed for a mean of 10 years, reported a relative risk of 0.88 (95% CI 0.80-0.98) per 10g of alcohol consumed per day.10 A cohort study in Japan with 89 MM cases followed for an average of 13 years found a non-significant 53% decreased relative risk for high vs. occasional alcohol intake among current drinkers,7 and a cohort study of female teachers in California with 101 MM cases followed for over 10 years found a non-significant decreased risk for current drinkers, particularly for lighter drinkers (RR=0.65, 95% CI 0.39-1.09), compared to nondrinkers.8 No clear evidence of an association was seen in the CPSII cohort,9 the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial,20 or in the San Francisco Health Care program.14 A large pooled case-control analysis of alcohol intake and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), a collection of lymphoid malignancies that are predominantly B-cell in origin, like MM, had findings very similar to our own, with alcohol consumption associated with reduced risk, particularly for current drinkers, but no dose-response relationship with consumption frequency or duration.21

The lack of dose-response associations in this study limits our interpretation for a true protective effect. Furthermore, the biological effects of alcohol and relationship to cancer are not clear. It has been suggested that light to moderate alcohol intake can attenuate proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines that may promote lymmphomagenesis,22-24 improve cellular and humoral immune responses, and improve DNA repair capacity.25 Also, antioxidants such as resveratrol in wine and flavonoids in beer may have anticarcinogenic effects.26,27 In contrast, heavy alcohol consumption has been shown to impair immune function and increase susceptibility to infection.28

Our study is, to our knowledge, the largest investigation of alcohol consumption and MM risk in men and women. As a consequence, we had excellent power to detect associations of weak magnitude, whereas the majority of previous investigations had low power to detect a statistically significant association of the magnitude of the OR of 0.73 that we observed in this study. Another strength of our analysis was the availability of extensive data on other putative demographic and lifestyle risk factors for MM with which we were able to evaluate confounding and effect modification.

An inherent limitation of this study is the retrospective case-control design of the participating studies, in which information on alcohol consumption was collected after disease diagnosis for cases. Although alcohol drinking status was based on participants’ usual drinking behavior prior to illness, the critical window of exposure may not be captured in retrospective case-control studies since the effects of alcohol are based on consumption close to time of diagnosis. Not having a clearly defined reference period, such as one to three years prior to diagnosis, across all studies limited our ability to rule out potential disease effects prior to diagnosis. We were able to exclude former drinkers who had ceased drinking within the two years prior to the completion of the questionnaire since these participants would be most subject to some influence of preclinical disease on alcohol use. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that our findings could be due to confounding of unascertained or unknown risk factors, or a reflection of selection bias due to differential participation or exposure misclassification between cases and controls. We did not have data on the presence of other medical conditions, such as autoimmune disorders, that may have led to participants avoiding alcohol. However, we note that the results from several prospective cohorts, including the largest cohort analysis of alcohol and MM conducted to date, support our findings.

In conclusion, our pooled analysis suggests that people who drink alcoholic beverages have a lower risk of MM. A pooled analysis among prospective cohorts with sufficiently detailed alcohol consumption data would be a valuable source of further confirmation of the present findings. If confirmed, the data collectively suggest that alcohol consumption may protect against this rare, highly fatal malignancy. Nevertheless, the biologic mechanisms underlying this association need to be elucidated further before we can state that alcohol consumption may confer true biologic protection, particularly since alcohol is linked to an increased risk of some adverse health outcomes and so may have limited value in prevention of MM.

Supplementary Material

Novelty & Impact.

To our knowledge, this is the largest analysis of alcohol consumption and multiple myeloma risk in men and women; therefore, we had excellent power to detect modest associations. Also, we were able to evaluate confounding and effect modification by putative risk factors. Our findings suggest that alcohol consumption may be associated with reduced risk of multiple myeloma, and point to the need for pooled analyses of cohort studies to better understand this relationship.

Acknowledgements

Funding for the Utah study was in part from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society 6067-09 (NJC) and the NCI CA152336 (NJC). Data collection for the Utah resource was made possible by the Utah Population Database (UPDB) and the Utah Cancer Registry (UCR). Partial support for all datasets within the UPDB was provided by the University of Utah Huntsman Cancer Institute (HCI) and the HCI Cancer Center Support grant, P30 CA42014 from the NCI. The UCR is funded by contract HHSN261201000026C from the NCI SEER program with additional support from the Utah State Department of Health and the University of Utah.

The work was supported by the European Regional Development Fund and the State Budget of the Czech Republic (RECAMO, CZ.1.05/2.1.00/03.0101).

The work conducted by Brenda Birmann was supported in part by grants from the NCI (K07 CA115687, CA149445) and the American Cancer Society (RSG-11-020-01-CNE).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors of this paper have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society . Cancer Facts & Figures 2012. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baris D, Brown LM, Andreotti G, Devesa SS. Epidemiology of Multiple Myeloma. In: Wiernik PH, Goldman JM, Dutcher JP, Kyle RA, editors. Neoplastic Diseases of the Blood. Springer; New York: 2013. pp. 547–64. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown LM, Pottern LM, Silverman DT, Schoenberg JB, Schwartz AG, Greenberg RS, Hayes RB, Liff JM, Swanson GM, Hoover R. Multiple myeloma among Blacks and Whites in the United States: role of cigarettes and alcoholic beverages. Cancer Causes Control. 1997;8:610–4. doi: 10.1023/a:1018498414298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nieters A, Deeg E, Becker N. Tobacco and alcohol consumption and risk of lymphoma: results of a population-based case-control study in Germany. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:422–30. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gorini G, Stagnaro E, Fontana V, Miligi L, Ramazzotti V, Amadori D, Rodella S, Tumino R, Crosignani P, Vindigni C, Fontana A, Vineis P, Seniori Costantini A. Alcohol consumption and risk of Hodgkin’s lymphoma and multiple myeloma: a multicentre case-control study. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:143–8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hosgood HD, 3rd, Baris D, Zahm SH, Zheng T, Cross AJ. Diet and risk of multiple myeloma in Connecticut women. Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18:1065–76. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-9047-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanda J, Matsuo K, Inoue M, Iwasaki M, Sawada N, Shimazu T, Yamaji T, Sasazuki S, Tsugane S, Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study Group Association of alcohol intake with the risk of malignant lymphoma and plasma cell myeloma in Japanese: a population-based cohort study (Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:429–34. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang ET, Clarke CA, Canchola AJ, Lu Y, Wang SS, Ursin G, West DW, Bernstein L, Horn-Ross PL. Alcohol consumption over time and risk of lymphoid malignancies in the California Teachers Study cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172:1373–83. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gapstur SM, Diver WR, McCullough ML, Teras LR, Thun MJ, Patel AV. Alcohol intake and the incidence of non-hodgkin lymphoid neoplasms in the cancer prevention study II nutrition cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176:60–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kroll ME, Murphy F, Pirie K, Reeves GK, Green J, Beral V. Alcohol drinking, tobacco smoking and subtypes of haematological malignancy in the UK Million Women Study. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:879–87. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown LM, Gibson R, Burmeister LF, Schuman LM, Everett GD, Blair A. Alcohol consumption and risk of leukemia, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and multiple myeloma. Leuk Res. 1992;16:979–84. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(92)90077-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monnereau A, Orsi L, Troussard X, Berthou C, Fenaux P, Soubeyran P, Marit G, Huguet F, Milpied N, Leporrier M, Hemon D, Clavel J. Cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, and risk of lymphoid neoplasms: results of a French case-control study. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:1147–60. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allen NE, Beral V, Casabonne D, Kan SW, Reeves GK, Brown A, Green J, Million Women Study Collaborators Moderate alcohol intake and cancer incidence in women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:296–305. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klatsky AL, Li Y, Baer D, Armstrong MA, Udaltsova N, Friedman GD. Alcohol consumption and risk of hematologic malignancies. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19:746–53. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng T, Holford TR, Leaderer B, Zhang Y, Zahm SH, Flynn S, Tallini G, Zhang B, Zhou K, Owens PH, Lan Q, Rothman N, Boyle P. Diet and nutrient intakes and risk of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in Connecticut women. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;59:454–66. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moysich KB, Bonner MR, Beehler GP, Marshall JR, Menezes RJ, Baker JA, Weiss JR, Chanan-Khan A. Regular analgesic use and risk of multiple myeloma. Leuk Res. 2007;31:547–51. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2006.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.IARC . Alcohol Consumption and Ethyl Carbamate. Vol. 96. International Agency for Research on Cancer; Lyon: IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Viechtbauer W. Confidence intervals for the amount of heterogeneity in meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2007;26:37–52. doi: 10.1002/sim.2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiu BC, Cerhan JR, Gapstur SM, Sellers TA, Zheng W, Lutz CT, Wallace RB, Potter JD. Alcohol consumption and non-Hodgkin lymphoma in a cohort of older women. Br J Cancer. 1999;80:1476–82. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Troy JD, Hartge P, Weissfeld JL, Oken MM, Colditz GA, Mechanic LE, Morton LM. Associations between anthropometry, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171:1270–81. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morton LM, Zheng T, Holford TR, Holly EA, Chiu BC, Costantini AS, Stagnaro E, Willett EV, Dal Maso L, Serraino D, Chang ET, Cozen W, et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a pooled analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:469–76. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70214-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szabo G, Mandrekar P, Girouard L, Catalano D. Regulation of human monocyte functions by acute ethanol treatment: decreased tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-1 beta and elevated interleukin-10, and transforming growth factor-beta production. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:900–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb05269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blanco-Colio LM, Muñoz-García B, Martín-Ventura JL, Alvarez-Sala LA, Castilla M, Bustamante A, Lamuela-Raventós RM, Gómez-Gerique J, Fernández-Cruz A, Millán J, Egido J. Ethanol beverages containing polyphenols decrease nuclear factor kappa-B activation in mononuclear cells and circulating MCP-1 concentrations in healthy volunteers during a fat-enriched diet. Atherosclerosis. 2007;192:335–41. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smedby KE, Askling J, Mariette X, Baecklund E. Autoimmune and inflammatory disorders and risk of malignant lymphomas--an update. J Intern Med. 2008;264:514–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.02029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pool-Zobel BL, Dornacher I, Lambertz R, Knoll M, Seitz HK. Genetic damage and repair in human rectal cells for biomonitoring: sex differences, effects of alcohol exposure, and susceptibilities in comparison to peripheral blood lymphocytes. Mutat Res. 2004;551:127–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jang M, Cai L, Udeani GO, Slowing KV, Thomas CF, Beecher CW, Fong HH, Farnsworth NR, Kinghorn AD, Mehta RG, Moon RC, Pezzuto JM. Cancer chemopreventive activity of resveratrol, a natural product derived from grapes. Science. 1997;275:218–20. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5297.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gerhäuser C. Beer constituents as potential cancer chemopreventive agents. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:1941–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nelson S, Kolls JK. Alcohol, host defense and society. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:205–9. doi: 10.1038/nri744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.