Abstract

Hydrogen sulfide-releasing aspirin (HS-ASA) is a novel compound with potential against cancer. It inhibited the growth of Jurkat T-leukemia cells with an IC50 of 1.9 ± 0.2 µM whereas that of ASA was >5000 µM. It dose-dependently inhibited proliferation and induced apoptosis in these cells, causing a G0/G1 cell cycle arrest. HS-ASA down-regulated β-catenin protein levels and reduced mRNA and protein expression of β-catenin/TCF downstream target genes cyclinD1 and c-myc. Aspirin up to 5 mM had no effect on β-catenin expression. HS-ASA also increased caspase-3 protein levels and dose-dependently increased its activity. These effects were substantially blocked by z-VAD-fmk, a pan-caspase inhibitor.

Keywords: Leukemia, β-catenin, caspase-3, hydrogen sulfide, apoptosis, proliferation, cell cycle

1. Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the primary cause of cancer-related mortality in children [1]. Survival rates of T-cell ALL (T-ALL) patients have improved due to strong supportive care with chemotherapy with a cure rate of more than 80% in children [2]. In spite of these improvements, novel and less toxic treatment strategies for T-ALL are needed. Novel therapies may target aberrantly activated signaling pathways influencing the proliferation, survival, and drug resistance of these T-ALLs. The β-catenin signaling pathway is of significance in cell proliferation and survival in some leukemias. Some reports indicated that β-catenin is essential for the survival and self-renewal of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) [3]. Several T-ALL leukemia cell lines, tumor lines of hematopoietic origin and primary leukemia cells express β-catenin that regulates cell-cell adhesion and transcription. Therefore, overall there is evidence that β-catenin may promote leukemia cell proliferation, adhesion, and survival. However, normal peripheral blood T cells do not express large amounts of β-catenin [4].

Considerable body of evidence has established nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in general and aspirin in particular as the prototypical chemopreventive agents against cancer. Recently, Rothwell et al. [5] reported that daily aspirin use, whether regular strength or low dose, resulted in reductions in cancer incidence and mortality. Moreover, the same group has also reported that aspirin prevented distant metastasis [6]. However, there are no reports that we are aware of regarding the use of NSAIDs and prevention of leukemia. Regular NSAID use may have serious gasterointestinal and renal side effects, which precludes their widespread use (reviewed in [7]). In searching for a better NSAID, various approaches have been implemented. One such approach has been the development of hydrogen sulfide-releasing NSAIDs [8–11]. Hydrogen sulfide-releasing aspirin (HS-ASA has been shown to have significant potential against cancer [12–14]. It consists of traditional ASA molecule covalently bound to an H2S-releasing moiety (5-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-3H-1,2-dithiole-3-thione). The rational for its development was based on the observation that H2S enhanced the local defense mechanisms within the stomach mucosa [15, 16], thereby in effect replacing the reductions in local prostaglandin levels.

HS-NSAIDs, including HS-ASA, profoundly affect cancer cell renewal and death [12, 13]. We have demonstrated that HS-ASA inhibits the growth of human cancer cell lines of colorectal, breast, pancreas, lung, prostate and leukemia far more potently than ASA [13]. In this study, we examined the effects of HS-ASA on growth and cell kinetics using Jurkat T-acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells which are known to express high levels of β-catenin [4, 17].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

HS-aspirin (HS-ASA), [4-(5-thioxo-5H-1, 2-dithiol-3-yl)-phenyl 2-acetoxybenzoate] was synthesized and purified by us with 1H-NMR verification as previously described [13], Fig 1A. Traditional ASA and fine chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Stock (100 mM) solutions of HS-ASA and ASA were prepared in DMSO (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ). The iQ5 SYBR Green Supermix, microplates, tubes and the Microseal B Adhesive seals used in real-time studies (RT-PCR) were from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). The TaqMan reverse transcription kit and Quant-iT RNA BR assay kits (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), RNeasy mini kit, the QIAshredder spin columns and the RNase-Free DNase Set (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) were used for qPCR studies. All primers were designed and synthesized by RealTimePrimers.com (Elkins Park, PA). The compounds MG-132, carbobenzoxyl-leucinyl-leucinyl-leucinal (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) and Bortezomib, [(1R)-3-methyl-1-({(2S)-3-phenyl-2-[(pyrazin-2-ylcarbonyl)amino]propanoyl}amino)butyl]boronic acid (Selleck, Houston, TX) were used as proteasomal inhibitors, and zVAD-FMK (Selleck, Houston, TX) was used as a pancaspase inhibitor.

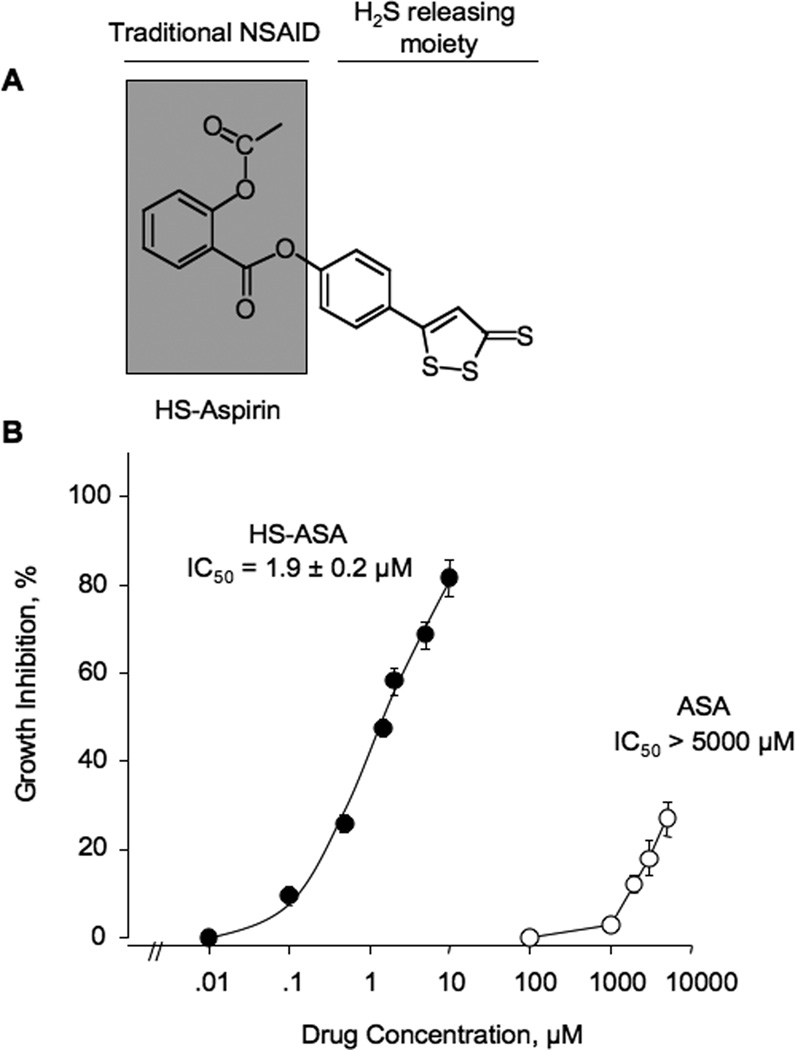

Figure 1.

Inhibitory effect HS-ASA on Jurkat T cell growth. (A) The structural components of HS-ASA. (B) Cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of the HS-ASA or ASA for 24h. Cell viability was determined by MTT assay as described in Section 2. Results are means ± SEM of three different experiments performed in triplicate.

2.2. Cell culture

Jurkat T-leukemia cells and SW480 human colon cancer cells were obtained from American Type Tissue Collection (Manassas, VA). The Jurkat T-leukemia cells were grown as a suspension culture and the SW480 cells as adherent cells using RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, BRL, Life Technologies, Inc.) supplemented with 10% FCS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin, grown at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. The final DMSO concentration was adjusted in all media to 1%. Viability was determined by the trypan blue dye exclusion method.

2.3. Cell viability analysis

Cell growth inhibitory effect of HS-ASA and ASA was measured using a colorimetric MTT assay kit (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Jurkat T-leukemia and SW480 colon cancer cells were plated in 96-well plates at a density of 30,000 cells/well. Following overnight incubation, the cells were treated for 24 hrs with different concentrations of HS-ASA or ASA. Role of caspases on cell growth inhibition by HS-ASA was examined by pretreatment with zVAD-FMK at final concentration of 50µM for 30 min. Viable cells were quantified with MTT substrate according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Growth inhibition was expressed as percentage of the corresponding control.

2.4. Cell kinetic studies

Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) was determined using an ELISA kit (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA), in accordance with the manufacturers protocol and as previously described [13]. For apoptosis, Jurkat T cells (105 cells/mL) were treated for 24 h with various concentrations of HS-ASA, washed with and resuspended in 1× Binding Buffer (Annexin V binding buffer, 0.1 M HEPES/NaOH (pH 7.4), 1.4 M NaCl, 25 mM CaCl2; BD BioSciences Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). Then, 5 mL of Annexin V-FITC (final concentration: 0.5 mg/mL) was added followed by propidium iodide as a counter stain (final concentration 20 mg/mL). The cells were then incubated at room temperature for 15 min in the dark and subjected to FACS analysis. Apoptotic cells were quantified using a Becton Dickinson LSR II equipped with a single argon ion laser. For each subset, about 10,000 events were analyzed. All parameters were collected in list mode files. Data was analyzed by Flow Jo software.

For cell cycle analysis, cells treated with various concentrations of HA-ASA were fixed in 100% methanol for 10 min at −20°C, pelleted (5000 rpm ×10 min at 4°C), resuspended and incubated in PBS containing 1% FBS/0.5% NP-40 on ice for 5 min. Cells were washed again in 500 µL of PBS/1% FBS containing 40 mg/mL propidium iodide (used to stain for DNA) and 200 µg/mL RNase type IIA, and analyzed within 30 min by flow cytometry. The percentage of cells in G0/G1, G2/M, and S phases was determined from DNA content histograms. Cell cycle phase distributions of control and treated cells were obtained and analyzed as described above.

2.5. Western blot analysis

β-Catenin, cyclin D1, c-myc, and caspase-3 expressions were assayed by immunoblotting proteins from cells treated with HS-ASA at 24 hr. When the effects of proteasomal inhibitors were examined, cells were co-treated with HS-ASA at the concentrations indicated ± Bortezomib (10 nM) or MG132 (1 µM), as previously described [18, 19]. Post- harvest of the cells, protein extracts were prepared in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate; 0.1% SDS; 0.5% NP-40) supplemented with proteinase inhibitor cocktail and dissolved in Laemmli sample buffer. Thirty micrograms of total protein were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and electro blotted on nitrocellulose membranes before immunodetection with the indicated antibody was performed. Primary mouse monoclonal antibodies were against β-catenin (1:1000 dilution; BD-Transduction Laboratories, San Jose, CA), cyclin D1 and c-Myc (clone DCS-6 and 9E10, respectively, 1:1000 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and α-actin (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Rabbit-anti-mouse-IgG peroxidase (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA) was used as secondary conjugated antibody for visualization of the proteins by ECL (Pierce Chemicals, Rockford, IL).

2.6. Preparation and characterization of RNA from cells, cDNA synthesis, quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

Jurkat cells were harvested, washed with PBS and lysed with the RLT buffer containing 1% mercaptoethanol and passed through the QIAshredderspin columns. RNA from cells was isolated using the RNeasy kit and subjected to on-column DNase digestion for 15 min at room temperature. RNA concentration was estimated using Quant-iT RNA BR Assay Kit and Qubit Fluorometer (Life Technologies, Chicago, IL) as described in the manufacturer’s protocol. The TaqMan reverse transcription kit as used for cDNA synthesis as described in the manufacturer’s protocol. In brief, 2.5 µM random hexamers were used in a 25 µL reaction with 500 ng of total RNA, primed at 25°C/10 min followed by reverse transcription at 48°C/30 min and final inactivation of RT at 95°C/5 min. Gene expression analysis by qPCR was carried out in 96 well plates using iCycler thermal cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The iCycler v3.1 Optical System Software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) was used to collect control thermocycler base and to collect the data. The qPCR mixes consisted of 12.5 µL of iQ5 SYBR Green Supermix, 10 ng of cDNA and forward and reverse primers for BCTNN1, CCND1, MYC and ACTB in 25 µL final volume per well. The sequences are patented by RealtimePrimers, Inc (Elkins Park, PA) and are available on their website. Thermocycling protocol was followed per manufacturer’s recommendation. In brief, Taq polymerase was activated by heating at 95°C for 3 minutes, followed by 40 two-step cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 seconds and annealing/extension at 60°C for 45 seconds. The fluorescence was measured after the extension step. Melt curves were generated to verify specificity of PCR amplification by heating at 95°C for 1 minute, then cooling at 55°C for 1 minute, followed by heating with a rate of 0.4°C for 10 seconds for a total of 100 repeats (end point at 95°C). The data files were analyzed using the iQ5 Optical System Software (Bio-Rad). Raw Ct values along with a combination of sample/target identifiers were exported from the iQ5 software and the resulting Excel files were subsequently imported into qbasePLUS (Biogazelle NV, Zwijnarde, Belgium, EU, [20], http://www.biogazelle.com/support/qbasePLUS/manual). Automated extraction of well information with regard to samples and targets took place during the imports. We used the following calculation parameters: one target amplification efficiency for all targets and average Cq calculated as a median of technical replicates. Stability of reference genes was first determined using geNorm statistical analysis [21] built-into the qbasePLUS. The relative quantification method was used to calculate Delta Delta Ct values to determine fold change in expression. Stability of reference genes was first determined using geNorm statistical analysis [21] built-into the qbasePLUS.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± SEM for at least three different sets of plates and treatment groups. Statistical comparison among the groups was performed using a one-way analysis of variance followed by the least significant difference method.

3. Results

3.1. HS-ASA inhibits the growth of Jurkat T cells

The growth inhibitory effect of HS-ASA was evaluated by the MTT assay in Jurkat T cells. HS-ASA had a significant growth inhibitory effect on these cells in a concentration-dependent manner, with an IC50 of 1.9 ± 0.2 µM whereas the IC50 for ASA was greater than 5000 µM at 24h (Fig 1B). Therefore, the ratio of the IC50s of ASA/HS-ASA is > 2600 suggesting that HS-ASA is at least 2600-fold more potent than traditional ASA in inhibiting the growth of this cell line. For further studies, we used the various multiple amounts of the IC50 concentrations, corresponding to 0.5× (1µM), 1× (2 µM), and 2×IC50 (4 µM). Recently, we had reported the effect of HS-ASA on eleven human cancer cell lines of six different tissue origins, that being of colon, breast, pancreatic, prostate, lung, and leukemia [13]. Of these, SW480 human colon cancer cells, expresses high levels of β-catenin [22]. We therefore, also used this cell line in some of our studies to evaluate whether our observation were cell line specific or not. HS-ASA inhibited the growth of SW480 cell line with an IC50 of 1.6 ± 0.5 µM at 24 hr. This is in line with our previous reported value of 1.8 ± 0.6 µM [13].

3.2. HS-ASA alters cell cycle kinetics and induces apoptosis

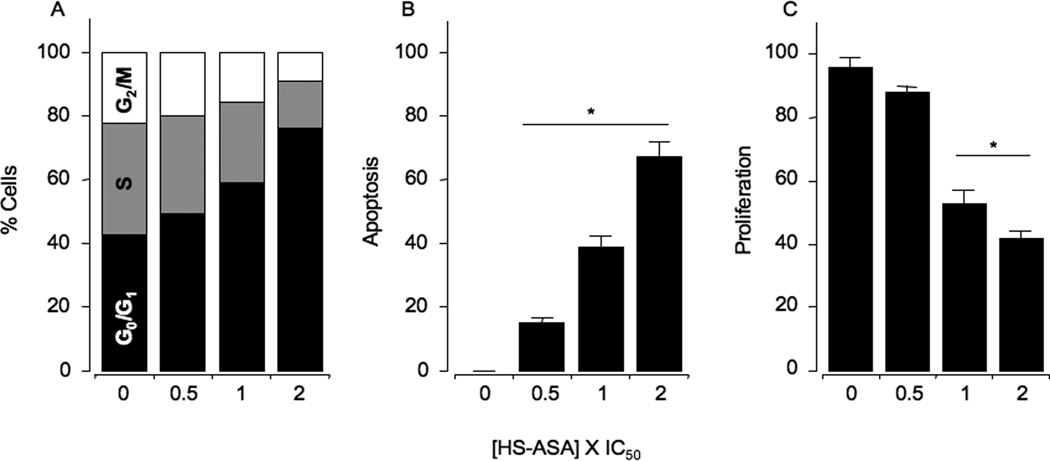

Human Jurkat T cells were treated with 0.5×, 1×, and 2×IC50 HS-ASA for 24 h as detailed in Methods, followed by flow cytometry analysis. The G1 population of cells was substantially increased from 42.5% in the vehicle treated cells (controls) to 49.1%, 58.6%, and 76.1% at 0.5×IC50, 1×IC50, and 2×IC50, respectively. This was accompanied by a dose-dependent reduction in the S and G2/M phases, suggesting a G0/G1 block (Fig 2A). HS-ASA also dose-dependently increased the Annexin V-FITC stained apoptotic population of cells, to 15 ± 2%, 39 ± 3%, and 67 ± 5% at 0.5×IC50, 1×IC50, and 2X×C50, respectively compared to control (Fig 2B). Cell proliferation (PCNA expression) was dose-dependently decreased by HS-ASA to 88 ± 2%, 63 ± 2%, 42 ± 3%, at 0.5×IC50, 1×IC50, and 2×IC50,respectively (Fig 2C).

Figure 2.

HS-ASA causes G0/G1 cell cycle arrest, induces apoptosis, and inhibits proliferation. Asynchronous Jurkat T cells were treated for 24 hours with either solvent or HS-ASA. Cells were harvested, and analyzed by flow cytometry as described is Section 2. The amount of G0/G1, S, and G2/M cell populations (Panel A) was demonstrated by DNA histograms. Results are representative of two different experiments. This study was repeated twice generating results within 10% of those presented here. Apoptosis (Panel B) and proliferation (Panel C) were determined as described in Section 2. Results are mean ± SEM of three different experiments. *P < 0.05 compared with untreated cells.

3.3. HS-ASA induces caspases activity

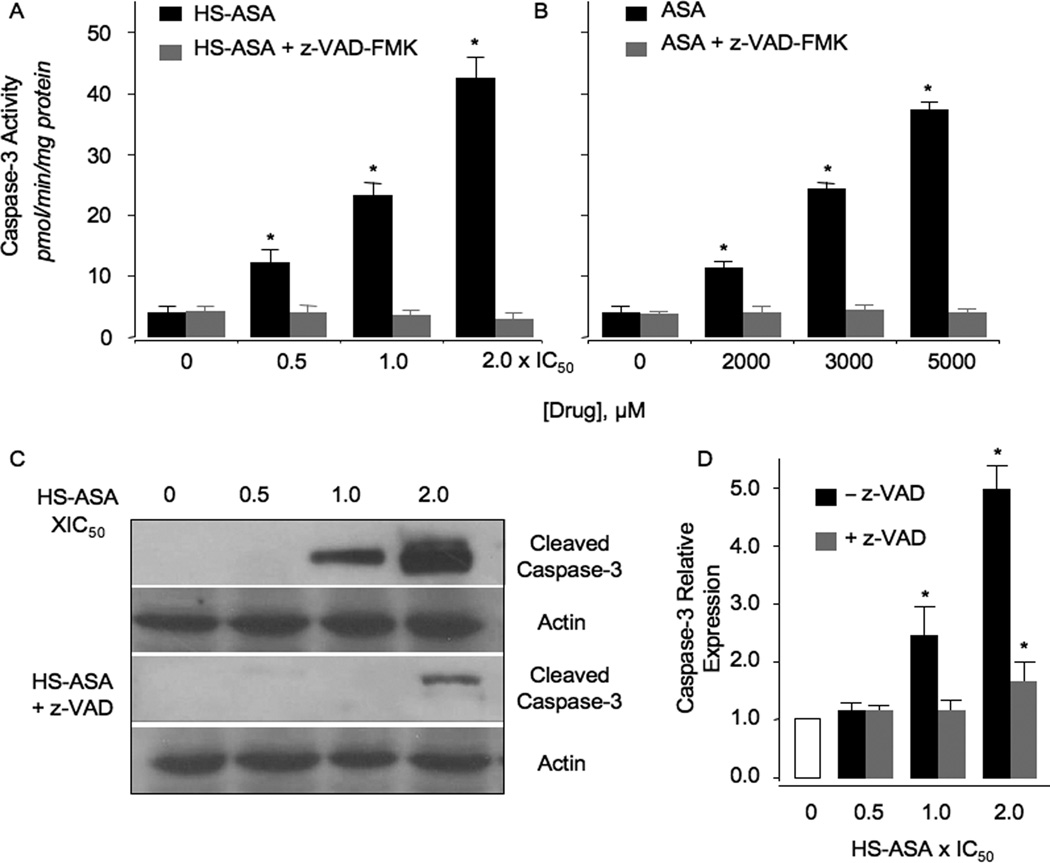

In some B and T cell leukemias, ASA and its nitric oxide donating derivatives are reported to activate caspases [23–26]. Since we obtained apoptotic populations in Jurkat T cells by HS-ASA, we investigated caspase-3 activation by HS-ASA and ASA. HS-ASA increased caspase-3 enzymatic activity in a dose-dependent manner at 6 hr. Compared to control, 0.5×IC50, 1×IC50, and 2×IC50 HS-ASA induced caspase-3 enzyme activity from 3.9 ± 0.3 pmol/min/mg protein to 12.3 ± 0.5, 23.3 ± 0.7, and 42.6 ± 1.2 pmol/min/mg protein, respectively (Fig 3A). ASA also dose-dependently increased capsae-3 enzyme activity from 4.2 ± 0.2 pmol/min/mg protein in untreated cell (control) to 11.6 ± 0.4, 25.2 ± 0.5, and 38.4 ± 1.4 pmol/min/mg at 2000 µM, 3000 µM, and 5000 µM, respectively (Fig 3B). The pan-caspsase inhibitor z-VAD-fmk was able to completely abrogate HS-ASA-and ASA-mediated caspase-3 activation, confirming the specificity of the observed effects (Fig 3A and 3B). Examination of caspase-3 protein by immunoblotting confirmed a dose-dependent increase in cleaved caspase-3 levels, which was significant at 1×IC50 and 2×IC50, Fig 3C and 3D. Further, pretreatment with z-VAD-fmk effectively blocked these increases (Fig 3C and 3D), demonstrating it as a specific effect.

Figure 3.

Concentration-dependence of caspase-3 enzymatic activity and protein expression in Jurkat cells. Caspase-3 enzymatic activity was determined as a function of varying concentrations of HS-ASA (panel A) and ASA (panel B) after 24 hr of treatment. In parallel experiments, cells were pretreated with the caspase-3 inhibitor, z-VAD-fmk as described in Section 2. Panel C, HS-ASA caused concentration-dependent increases in caspase-3 protein expression. Results are mean ± SEM for 3 different cell preparations done in triplicate. *P < 0.05 compared to control untreated cells.

3.4. Caspase inhibitor reversed HS-ASA mediated Cell growth inhibition

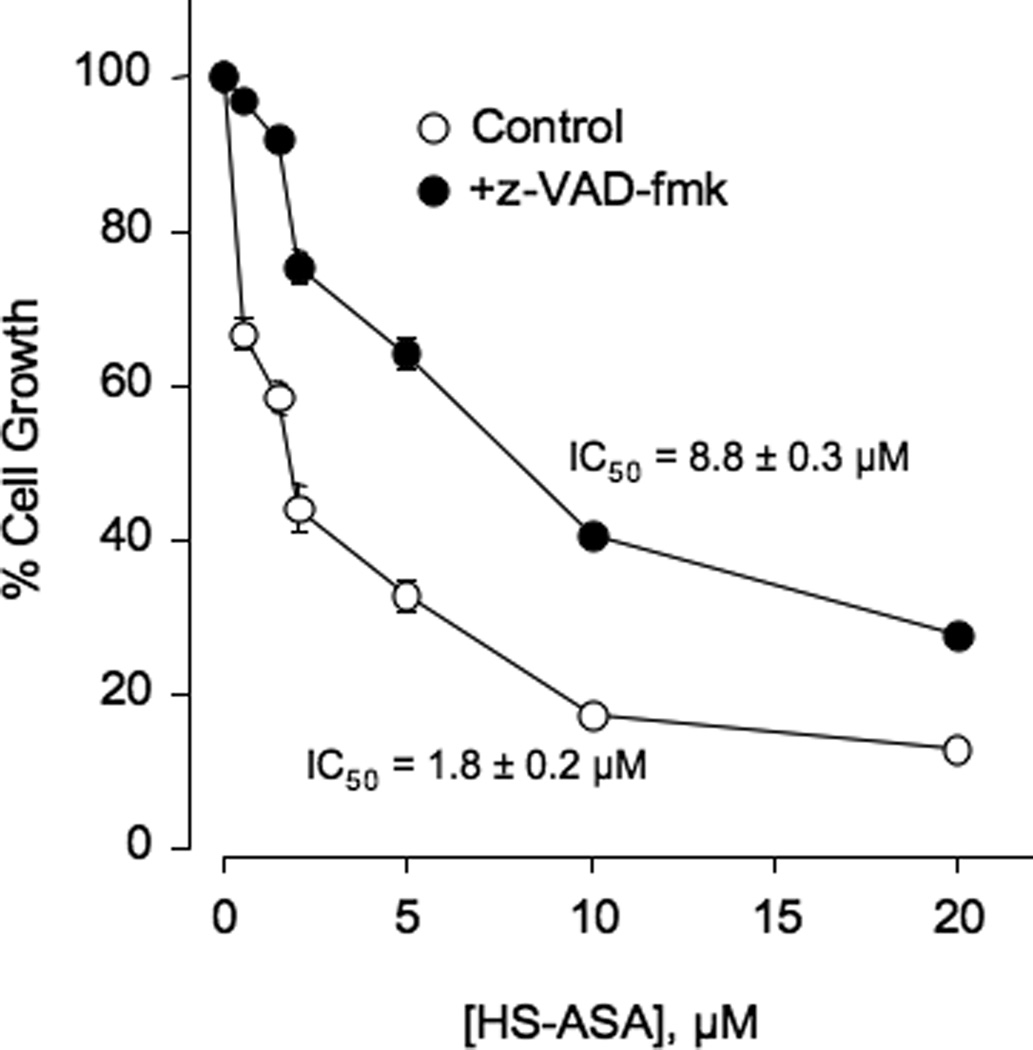

Jurkat cells were untreated or pretreated with 2 µM z-VAD-fmk for 4 hr and followed by treatment with different concentrations of HS-ASA for 24 hr and subsequently analyzed for growth inhibition by MTT assay. z-VAD-fmk partially reversed growth inhibition by HS-ASA and there was an almost 5-fold shift in the IC50 from 1.8 ± 0.2 µM to 8.8 ± 0.3 µM (Fig 4) thereby demonstrating the specific induction of apoptosis by HS-ASA through the well known apoptotic cascade enzymes. Complete reversal was not obtained, likely due to involvement of other pathways.

Figure 4.

HS-ASA mediated cell growth inhibition is reversed by z-VAD-fmk. Jurkat cells, pretreated with 2 µM z-VAD-fmk for 4 hr or untreated, were followed by different concentrations of HS-ASA for 24 hr and subsequently analyzed for growth as described in Section 2. Values represent means ± SEM of three representative experiments performed in triplicate.

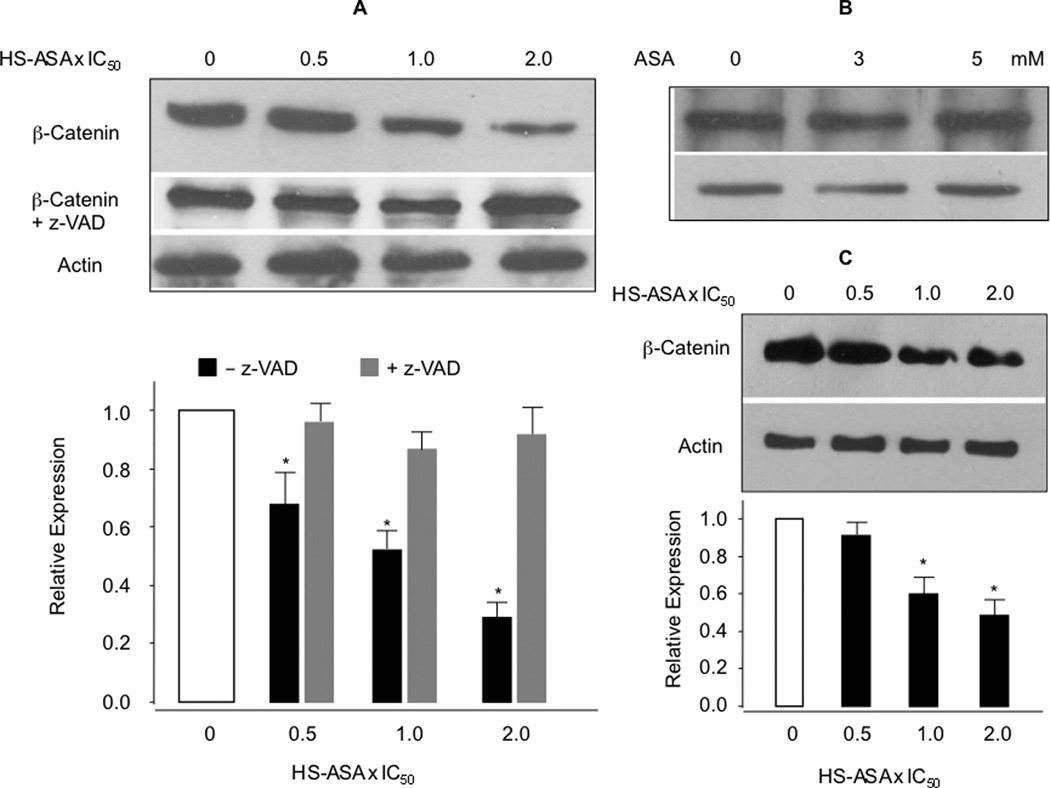

3.5. HS-ASA reduces β-catenin protein levels via caspases

We analyzed the total amount of β-catenin in response to HS-ASA and ASA in Jurkat T-leukemia cells. HS-ASA dose-dependently reduced the protein levels of β-catenin in the whole cell lysates, whereas ASA up to 5 mM had no effect on total β-catenin expression (Fig 5A and 5B). The reduction in total β-catenin expression by HS-ASA treatment was not cell type specific, since we also observed that HS-ASA dose-dependently reduced β-catenin protein expression in SW480 colon cancer cells (Fig 5C). However, β-catenin degradation products or partial degradation bands, represented by smaller fragments, were not observed in lysates of HS-ASA treated cells when compared to controls, even at various concentrations and time intervals less than 24 hrs (data not shown) in either of the cell lines. Comparison of the relative expression ratio of β-catenin with the growth inhibition in Jurkat T cells shows that at 1×IC50, which represents 50% inhibition of cell growth at 24 hours, there is approximately 50 to 55% reduction in β-catenin levels, and such correspondence of sequestering dose-dependence is encouraging. Since we did not locate partial breakdown fragments of β-catenin at any time point, we examined three possibilities that may lead to reduced β-catenin protein expression such as, increase in the proteasomal degradation process, the inhibition of mRNA expression of β-catenin, and finally, caspase-mediated degradation of β-catenin. Cells were co-treated with various concentrations HS-ASA ± the proteasome inhibitors Bortezomib (10 nM) or MIG132 (1 µM) and examined for possible accumulation of β-catenin. However, in stark contrast, at the concentrations indicated for these proteasome inhibitors and even at lower doses, there were marked reductions of β-catenin protein expression down to undetectable amounts in control lanes without or with HS-ASA. Therefore, ubiquitination changes could not be pursued further (data not shown). Next, mRNA levels of β-catenin, as measured by qRT-PCR from HS-ASA treated cells confirmed that β-catenin mRNA levels are not altered by HS-ASA at 24 h (Fig 6A) Finally, since caspase-mediated degradation of β-catenin has been demonstrated by a nitric oxide-donating derivative of aspirin [24], we therefore examined whether the observed decrease in β-catenin could be reversed by the pan caspases inhibitor z-VAD-fmk. Figure 5A (lower panel) shows that HS-ASA mediated β-catenin decrease was substantially blocked by z-VAD-fmk, especially notable at 2×IC50 HS-ASA. This strongly suggetsts that caspases mediate the reduction of β-catenin levels by cleavage and degradation, and therefore, agrees with the partial reversal of growth inhibition shown in Fig 4.

Figure 5.

HS-ASA decreases β-catenin levels. Jurkat and SW480 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of HS-ASA or ASA for 24 h and analyzed for total β-catenin expression by immunoblot of the lysates. Panels (A) and (C) show concentration-dependent reductions of β-catenin in Jurkat and SW80 cells respectively; panel (B) shows that increasing concentrations of ASA had no effect on total β-catenin in Jurkat cells. The blots were reprobed for α-actin. The blots are representative of 3 different experiments, the bar graphs in (A) and (C) are mean ± SEM of three different blots normalized against their respective α-actin. *P < 0.05 compared to no treatment.

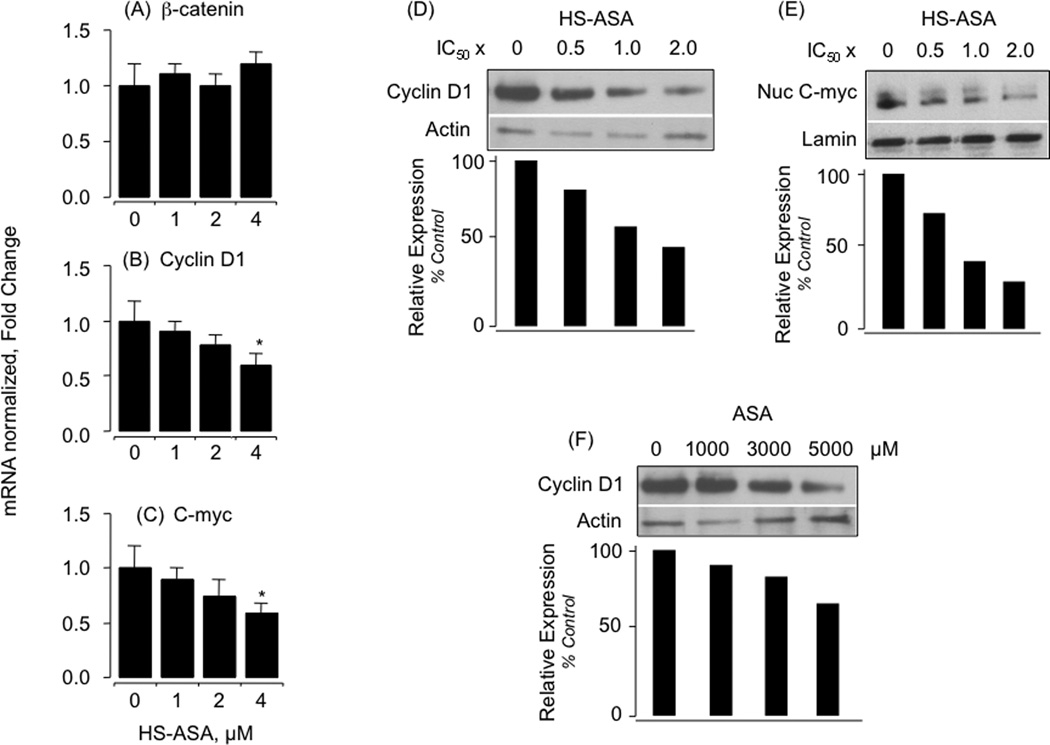

Figure 6.

Effect of HS-ASA on β-catenin, cyclin D1 and c-myc mRNA levels and effects of HS-ASA and ASA on cyclin D1 and c-myc protein expression. Using Jurkat cells, levels of β-catenin, cyclin D1 and c-myc mRNA (panels A, B, and C respectively) were measured after 24 h of treatment with HS-ASA using qRT- PCR with gene specific primers followed by real time detection and normalized to β-actin as described in Section 2. Results are mean ± SEM of 4 different determinations. *P < 0.05 compared to no treatment. For effects of HS-ASA on cyclin D1 and c-myc protein levels, Jurkat cells were treated with increasing concentrations HS-ASA for 24h and analyzed as described in Section 2. Cyclin D1 and c-myc protein levels were reduced by HS-ASA in a concentration-dependent manner (panels D and E respectively). Cyclin D1 protein levels were also reduced by ASA in a concentration-dependent manner (panel F). Results are representative of two different experiments. The results of the duplicate experiments were within 15% of each other.

Of the several of genes whose transcription is regulated by β-catenin/TCF-4, Cyclin D1 plays an important role in the process of carcinogenesis [27]. Therefore, we also analyzed the mRNA levels and protein expression of β-catenin/TCF transcriptional targets, cyclin D1 and c-myc, following HS-ASA treatment for 24 h for control at 1 µM, 2 µM and 4 µM concentrations. Levels of cyclin D1, c-myc, mRNA were determined by RT-qPCR. There was a concentration-dependent decrease in cyclin D1 and c-myc mRNA levels at 24 h (Fig 6B and 6C, respectively) and this was associated with reduction of their protein levels at 24 h (Fig 6D and 6E, respectively). Intriguingly, ASA also reduced cyclin D1 protein expression, which was substantial only at the highest dose, 5000 µM (Fig 6F). ASA-mediated reduction in cyclin D1 protein without upstream reduction of β-catenin levels implies modulation of TCF-4/β-catenin signaling by other mechanisms and agrees with reports in other cell types such as in colorectal cell lines [28]. Therefore in this study, HS-ASA decreased β-catenin protein levels, overall reduced cyclin D1 and c-myc message, which are in agreement with cell growth inhibition and G1 phase blockade.

4. Discussion

There are three major points of interest regarding HS-ASA’s effects in Jurkat T cells. Firstly, HS-ASA is more potent in inhibiting the growth of Jurkat T leukemia cells than its parent compound ASA, and other analogs of ASA such as nitric oxide-releasing aspirin (NO-ASA) [24], and therefore is potentially a strong candidate for further development. This strong effect was also observed in SW480 human colon cancer cell line, indicating tissue independence rather than being cell line specific.

Second, this is the first report describing the effects of this novel agent on β-catenin levels. This reduction in β-catenin levels is due to degradation of β-catenin by HS-ASA-mediated caspase activation, excluding the possibility of reduction in β-catenin mRNA expression. In the case of Jurkat cells, β-catenin reduction was more easily evident since this cell line is known to express moderate to high levels of β-catenin in the cytoplasm [4, 17]. Regarding caspase-3 activation, it is well accepted that β-catenin is cleaved by caspases, and in particular by caspase-3 [29–31]. Similar results were obtained in SW480 colorectal cancer cells that also express high levels of β-catenin (data not shown). Overall, the reduced β-catenin levels is a result of apoptosis induced by HS-ASA

Third, G0/G1 cell cycle block, induction of apoptosis, and inhibition of proliferation are the cellular mechanisms involved by HS-ASA. There is a clear indication that apoptosis contributes to the overall cell growth inhibition via capsase-3 activation, since z-VAD-fmk blocked the capsase-3 activity completely and partially reversed cell growth inhibition. Therefore, caspases are necessary for the observed effects. Considering the well known canonical β-catenin/TCF-4 signaling pathway, the demonstration of degradation of β-catenin levels associated with decreased cyclin D1 protein expression clearly imply this signaling pathway is affected.

The two gasotransmitters H2S and NO share many similar actions. Previously we had reported on the pro-apoptotic effect of NO-ASA in Jurkat T cells [24]. Others have shown that high concentrations of NO cause apoptosis and death of normal bone marrow hematopoietic cells [32], and cytotoxicity to acute leukemia cells [32]. H2S has also been reported to have pro-oxidant and pro-apoptotic effects in malignant cells, and have cytoprotective effects on most normal cells [33].

Future directions in this area may focus on the role of S-sulfhydration as a potential mechanism of action of HS-NSAIDs on target regulatory molecules. Overall, this study underscores the significance of this novel agent and its cellular and biochemical effects. HS-ASA strongly inhibits the growth of Jurkat T cells and causes inhibition of β-catenin expression. These studies suggest one mechanism by which HS-ASA inhibits the growth of Jurkat T cells and strongly suggest that this novel agent merits further evaluation against ALL.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute through a subcontract from ThermoFisher, contract # FBS-43312-26 and by NIH grant R24 DA018055. The funding agencies had no role in the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Abbreviations

- ALL

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- CML

Chronic Myeloid Leukemia

- NSAIDs

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- ASA

aspirin, HS-ASA, hydrogen sulfide-releasing aspirin

- NO

nitric oxide

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Authors' Contributions

Participated in research design: MC, NN, TS, KK

Conducted experiments: MC, RK, NN, ZYG, TS, SM

Performed data analysis: MC, NN, TS, SM, KK

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: MC, RK, NN, ZYG, TS, SM, KK

Conflict of interest

The authors reported no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Pui CH, Robison LL, Look AT. Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet. 2008;371:1030–1043. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60457-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartram CR, Schrauder A, Kohler R, Schrappe M. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children: treatment planning via minimal residual disease assessment. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109:652–658. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2012.0652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu Y, Chen Y, Douglas L, Li S. beta-Catenin is essential for survival of leukemic stem cells insensitive to kinase inhibition in mice with BCR-ABL-induced chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2009;23:109–116. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung EJ, Hwang SG, Nguyen P, Lee S, Kim JS, Kim JW, et al. Regulation of leukemic cell adhesion, proliferation, and survival by beta-catenin. Blood. 2002;100:982–990. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.3.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rothwell PM, Price JF, Fowkes FG, Zanchetti A, Roncaglioni MC, Tognoni G, et al. Short-term effects of daily aspirin on cancer incidence, mortality, and non-vascular death: analysis of the time course of risks and benefits in 51 randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2012;379:1602–1612. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61720-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rothwell PM, Wilson M, Price JF, Belch JF, Meade TW, Mehta Z. Effect of daily aspirin on risk of cancer metastasis: a study of incident cancers during randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2012;379:1591–1601. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60209-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kashfi K. Anti-inflammatory agents as cancer therapeutics. Adv Pharmacol. 2009;57:31–89. doi: 10.1016/S1054-3589(08)57002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li L, Rossoni G, Sparatore A, Lee LC, Del Soldato P, Moore PK. Anti-inflammatory and gastrointestinal effects of a novel diclofenac derivative. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:706–719. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sparatore A, Santus G, Giustarini D, Rossi R, Del Soldato P. Therapeutic potential of new hydrogen sulfide-releasing hybrids. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2011;4:109–121. doi: 10.1586/ecp.10.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lazzarato L, Chegaev K, Marini E, Rolando B, Borretto E, Guglielmo S, et al. New nitric oxide or hydrogen sulfide releasing aspirins. J Med Chem. 2011;54:5478–5484. doi: 10.1021/jm2004514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kashfi K, Olson KR. Biology and therapeutic potential of hydrogen sulfide and hydrogen sulfide-releasing chimeras. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;85:689–703. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chattopadhyay M, Kodela R, Nath N, Barsegian A, Boring D, Kashfi K. Hydrogen sulfide-releasing aspirin suppresses NF-kappaB signaling in estrogen receptor negative breast cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:723–732. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chattopadhyay M, Kodela R, Nath N, Dastagirzada YM, Velazquez-Martinez CA, Boring D, et al. Hydrogen sulfide-releasing NSAIDs inhibit the growth of human cancer cells: a general property and evidence of a tissue type-independent effect. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:715–722. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chattopadhyay M, Kodela R, Nath N, Street CR, Velazquez-Martinez CA, Boring D, et al. Hydrogen sulfide-releasing aspirin modulates xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes in vitro and in vivo. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:733–740. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wallace JL, Caliendo G, Santagada V, Cirino G, Fiorucci S. Gastrointestinal safety and anti-inflammatory effects of a hydrogen sulfide-releasing diclofenac derivative in the rat. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:261–271. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallace JL, Dicay M, McKnight W, Martin GR. Hydrogen sulfide enhances ulcer healing in rats. FASEB J. 2007;21:4070–4076. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8669com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsutsui J, Moriyama M, Arima N, Ohtsubo H, Tanaka H, Ozawa M. Expression of cadherin-catenin complexes in human leukemia cell lines. J Biochem. 1996;120:1034–1039. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen D, Frezza M, Schmitt S, Kanwar J, Dou QP. Bortezomib as the first proteasome inhibitor anticancer drug: current status and future perspectives. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2011;11:239–253. doi: 10.2174/156800911794519752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dillard AC, Lane MA. Retinol decreases beta-catenin protein levels in retinoic acid-resistant colon cancer cell lines. Mol Carcinog. 2007;46:315–329. doi: 10.1002/mc.20280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hellemans J, Mortier G, De Paepe A, Speleman F, Vandesompele J. qBase relative quantification framework and software for management and automated analysis of real-time quantitative PCR data. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R19. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-2-r19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vandesompele J, De Preter K, Pattyn F, Poppe B, Van Roy N, De Paepe A, et al. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002;3 doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. RESEARCH0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chapple KS, Cartwright EJ, Hawcroft G, Tisbury A, Bonifer C, Scott N, et al. Localization of cyclooxygenase-2 in human sporadic colorectal adenomas. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:545–553. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64759-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bellosillo B, Pique M, Barragan M, Castano E, Villamor N, Colomer D, et al. Aspirin and salicylate induce apoptosis and activation of caspases in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Blood. 1998;92:1406–1414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nath N, Labaze G, Rigas B, Kashfi K. NO-donating aspirin inhibits the growth of leukemic Jurkat cells and modulates beta-catenin expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;326:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu Y, Chen GQ. Effector caspases and leukemia. Int J Cell Biol. 2011;2011:738301. doi: 10.1155/2011/738301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Razavi R, Gehrke I, Gandhirajan RK, Poll-Wolbeck SJ, Hallek M, Kreuzer KA. Nitric oxide-donating acetylsalicylic acid induces apoptosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells and shows strong antitumor efficacy in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:286–293. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin Beta-catenin, a novel prognostic marker for breast cancer: its roles in cyclin D1 expression and cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4262–4266. doi: 10.1073/pnas.060025397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dihlmann S, Siermann A, von Knebel Doeberitz M. The nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs aspirin and indomethacin attenuate beta-catenin/TCF-4 signaling. Oncogene. 2001;20:645–653. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Webb SJ, Nicholson D, Bubb VJ, Wyllie AH. Caspase-mediated cleavage of APC results in an amino-terminal fragment with an intact armadillo repeat domain. FASEB J. 1999;13:339–346. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steinhusen U, Badock V, Bauer A, Behrens J, Wittman-Liebold B, Dorken B, et al. Apoptosis-induced cleavage of beta-catenin by caspase-3 results in proteolytic fragments with reduced transactivation potential. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:16345–16353. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001458200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van de Craen M, Berx G, Van den Brande I, Fiers W, Declercq W, Vandenabeele P. Proteolytic cleavage of beta-catenin by caspases: an in vitro analysis. FEBS Lett. 1999;458:167–170. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weinberg JB. Nitric Oxide and Life or Death of Human Leukemia Cells. In: Bonavida B, editor. Cancer Drug Discovery and Development Nitric Oxide (NO) and Cancer Prognosis, Prevention, and Therapy. Springer Science + Business Media, LLC; 2010. pp. 147–167. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Predmore BL, Lefer DJ, Gojon G. Hydrogen sulfide in biochemistry and medicine. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;17:119–140. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]