Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the added role of T1-weighted (T1w) gadolinium ethoxybenzyl diethylenetriamine penta-acetic acid (Gd-EOB-DTPA)-enhanced magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRC) compared with T2-weighted MRC (T2w-MRC) in the detection of biliary leaks.

Methods

Ninety-nine patients with suspected biliary complications underwent routine T2w-MRC and T1w contrast-enhanced (CE) MRC using Gd-EOB-DTPA to identify biliary leaks. Two observers reviewed the image sets separately and together. MRC findings were compared with those of surgery and percutaneous transhepatic cholangiopancreatography. The sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of the techniques in identifying biliary leaks were calculated.

Results

Accuracy of locating biliary leaks was superior with the combination of Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC and T2w-MRC (P < 0.05).The mean sensitivities were 79 % vs 59 %, and the mean accuracy rates were 84 % vs 58 % for combined CE-MRC and T2w-MRC vs sole T2w-MRC. Nineteen out of 21 patients with biliary-cyst communication, 90.4 %, and 12/15 patients with post-traumatic biliary extravasations, 80 %, were detected by the combination of Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC and T2w-MRC images, P < 0.05.

Conclusions

Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC yields information that complements T2w-MRC findings and improves the identification and localisation of the bile extravasations (84 % accuracy, 100 % specificity, P < 0.05). We recommend Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC in addition to T2w-MRC to increase the preoperative accuracy of identifying and locating extravasations of bile.

Key Points

• Magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRC) does not always detect bile leakage and cysto-biliary communications.

• Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC helps by demonstrating extravasation of contrast material into fluid collections.

• Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC also demonstrates the leakage site and bile duct injury type.

• Combined Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced and T2w-MRC can provide comprehensive information about biliary system.

• Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC is non-invasive and does not use ionising radiation.

Keywords: Gd-EOB-DTPA, Contrast enhanced MRC, MR cholangiography, Biliary leaks, Biliary tree

Introduction

Bile leaks can be seen after traumatic or iatrogenic bile duct injuries, with an estimated incidence ranging from 12 % to 41 %, and communication of a hydatid disease with the biliary tree has been described in up to 90 % of hepatic hydatid cysts [1, 2]. Precise and prompt preoperative localisation of bile leaks is instrumental in determining the surgical approach and reducing the extent of exploration and anaesthesia time [2]. Thus, morbidity and mortality rates can be reduced significantly. For the detection of biliary leakage, cross-sectional imaging studies including ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRC) are employed [3, 4]. Although these techniques provide highly suggestive findings for a diagnosis of biliary leaks in an appropriate clinical setting, they generally provide non-specific findings (e.g. fluid collection). Further investigation with invasive techniques such as percutaneous transhepatic cholangiopancreatography (PTC) or endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) is required to confirm the diagnosis by demonstration of active contrast extravasation from the biliary tree [4–6]. The current algorithm for searching for an extravasation of bile is to perform abdominal ultrasound and, if the findings are non-diagnostic, to perform T2-weighted (T2w) MRC, which highlights the biliary tree [7]. The accuracy rate of diagnosis and localisation of an extravasation of bile by T2w-MRC is within the range 70–74 % [8]. T1-weighted (T1w) contrast-enhanced MRC (CE-MRC) using hepatobiliary contrast agents such as gadobenate dimeglumine (Gd-BOPTA) and gadolinium ethoxybenzyl diethylenetriamine penta-acetic acid (Gd-EOB-DTPA) is a recently emerged technique with promising results with respect to its ability to visualise non-dilated bile ducts and biliary leaks [5–9]. Both Gd-BOPTA and Gd-EOB-DTPA are incorporated into the hepatocytes by an anionic transport system after the vascular phase. Approximately 3–5 % of the injected dose of Gd-BOPTA and 50 % of Gd-EOB-DTPA are excreted in the human biliary system [10, 11]. Therefore, Gd-EOB-DTPA may provide adequate biliary imaging within a shorter period of time (10–20 min) than Gd-BOPTA (60 min) [12]. Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC allows detection of active bile leakage and cysto-biliary communication by direct visualisation of contrast material extravasation into fluid collections and also demonstrates the anatomical site of the leakage and the type of bile duct injury [10–12].

Although few case reports demonstrated biliary leakage on contrast-enhanced MRC images, to the best of our knowledge, no previous study has investigated its added diagnostic value in comparison to T2w-MRC in a large series. Therefore, in this study we aimed to evaluate the diagnostic value of Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC added to T2w-MRC in the detection of post-traumatic and post-surgical biliary extravasations and cysto-biliary communications.

Materials and methods

Patients

This prospective study (over a period of 6 months) received institutional review board approval, and all of the patients gave written informed consent. One hundred and five patients (60 men and 45 women; mean age 55 ± 6.3 [SD], range 39–74 years) with suspected biliary leak were referred for MRC. Six patients were excluded owing to claustrophobia (n = 1), previous hypersensitivity to gadolinium (n = 2) and reduced glomerular filtration rate of less than 30 ml/min/1.73 m2 and increased total serum bilirubin over 17 mg/dl (n = 3). The remaining 99 patients (56 men [56.5 %] and 43 women [43.4 %]) constituted the study group and underwent T2w-MRC and T1w-Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC. The indications for MRC were suspected biliary leaks after cholecystectomy (n = 24); living donor liver transplantation (n = 14); patients with major liver resection (n = 6); pancreaticoduodenectomy (n = 5); following traumatic biliary tract injury (n = 20); surgical treatment of hydatid cysts (n = 21); [this group were divided into two subgroups: cystectomy (n = 16) and tube drainage of bile ducts (n = 5)]; and following percutaneous drainage of a hydatid cyst (n = 9); Table 1. The mean duration between MRC and trauma or surgical and interventional procedures was 3.4 ± 2.3 days (range, 1–5 days).

Table 1.

Types of surgical and interventional procedures carried out on the patients

| Patients | Male | Female | Mean age (years) | Surgical procedure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 24 | 17 | 7 | 42 | Cholecystectomy |

| n = 6 | 4 | 2 | 64 | Major liver resection |

| n = 14 | 8 | 6 | 53 | Orthotopic liver transplantation |

| n = 5 | 3 | 2 | 59 | Pancreaticoduodenectomy |

| n = 20 | 13 | 7 | 41 | Surgical treatment of traumatic bile tract injury |

| n = 16 | 9 | 7 | 44 | Cystectomy |

| n = 5 | 3 | 2 | 49 | Tube drainage |

| n = 9 | 4 | 5 | 48 | Percutaneous drainage of hydatid cyst |

MRC protocol

Conventional T2w-MRC and CE-MRC were performed using a 16-channel phased-array body surface coil on a 3-T MRI (Magnetom Skyra; Siemens Healthcare, Berlin, Germany) equipped with high performance gradients (maximum gradient, 45 mT/m; maximum slew rate, 200 T/m/s). First, T2w-MRC was acquired using half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo spin echo (HASTE) sequences (TR/TE, 2,000/698 ms; FA, 15°; 3-mm slice thickness; 256 × 134 matrix) in transverse and coronal planes. Multiplanar/maximum intensity projection (MPR/MIP) reconstructions specially designed to directly view the contents of the bile and pancreatic ducts were generated. CE-MRC was performed using breath-hold three-dimensional (3D) fat-suppressed gradient echo (GRE) T1w VIBE (volumetric interpolated breath-hold examination) sequence (TR/TE, 3.89/1.83 ms; FA, 15°; duration 18 s; 3-mm slice thickness; 256 × 115 matrix) after intravenous administration of 0.1 ml/kg (0.25 mmol/kg) Gd-EOB-DTPA (Primovist; Bayer Schering Pharma, Berlin, Germany) at a rate of 2 ml/s, followed by a bolus of 20 ml saline. Following an early dynamic phase in a transverse plane, the post-contrast T1w sequence was repeated in the transverse and coronal planes at 5, 10, 20, 30, 60 min for detection of the biliary extravasations. In 12 patients with suspected biliary-cyst communications, further delayed imaging at 180 min after intravenous administration of Gd-EOB-DTPA was carried out.

Image evaluation

Two experienced radiologists (13 and 5 years of experience in abdominal MR imaging) performed image evaluation by consensus; first, they assessed the images obtained by T2w-MRC and recorded all findings. In the post-transplantation and postoperative groups, information on the type of surgical procedure was obtained from operating surgeons before MRC image evaluation. After 3.4 ± 2.3 days, the same radiologists performed comparative assessment of the images obtained by T2w-MRC and T1w-CE-MRC by consensus. T1w-CE-MRC images were evaluated at 30-60 min after intravenous administration of Gd-EOB-DTPA for trauma and postoperative and transplantation group, respectively. In the hydatid cyst group, these images were evaluated at 60 min to 24 h after intravenous administration of Gd-EOB-DTPA. The following parameters were considered in analysis: biliary fistulas (into the peritoneal cavity); intraparanchymal biliary leakage (biloma); cysto-biliary communication; the Strasberg classification in the trauma group; timing of MRC after contrast agent administration. For each examination, the readers recorded the presence or absence of biliary leaks (e.g. fistulas, biloma or cysto-biliary communication) on T2w-MRC and the combined images (T1w-CE-MRC plus T2w-MRC). All MRC images were transferred to a workstation (Syngo Via console, software version 2.0; Siemens Medical Solutions, Berlin, Germany) for evaluation. After images from the MRC examinations had been reviewed by consensus, the sensitivity, specificity and accuracy rates for the presence or absence of biliary abnormalities were calculated for T2w-MRC and the combination of Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC and T2w-MRC. All MRC image findings were compared with the results of the surgical and interventional radiological evaluations findings, or clinical follow-up.

Correlation of MRC with surgical and/or interventional radiological findings

Two surgeons, with 15 and 12 years of experience with hepatobiliary and liver transplantation surgery, performed all surgical explorations. An interventional radiologist with 16 years of hepatobiliary experience performed all interventional radiology procedures. The main aim of surgical exploration and interventional procedures was to determine the site of bile leakage and provide treatment. Additionally, biliary tract injuries were determined. All surgical procedures were performed under general anaesthesia. However, all of the interventional radiological procedures were performed under local anaesthesia. All surgical and interventional radiological findings, including the location of the biliary leaks, were recorded (Table 2).

Table 2.

Biliary complications, (fistula or leakage) detected by surgical and interventional radiological procedure

| Complications a | Surgical and interventional radiological procedure | Type of biliary complications |

|---|---|---|

| n = 10 (41.7 %) | Cholecystectomy | 6 biliary leakages, 4 biliary fistulas |

| n = 3 (60 %) | Major liver resection | 2 biliary fistulas, 1 biliary leakage |

| n = 6 (42.8 %) | Orthotopic liver transplantation | 4 biliary leakages, 2 biliary fistulas |

| n = 3 (60 %) | Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 2 biliopancreatic fistulas, 1 biliary leakage |

| n = 15 (75 %) | Surgical treatment of trauma | 10 biliary leakages, 5 biliary fistulas |

| n = 19 (90 %) | Surgical treatment of hydatid cyst | 19 cysto-biliary communications |

| n = 8 (88 %) | Percutaneous drainage of hydatid cyst | 8 cysto-biliary communications |

a Percentage of complications for each surgical and interventional radiological procedure

Statistical analysis

We used the Fisher’s exact test to analyse the presence or absence of biliary abnormalities per site per patient in each group with the use of T2w-MRC and combined Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC and T2w-MRC. In all cases, a two-tailed P value was determined, and the null hypothesis was rejected at P < 0.05 (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of P values with surgical and interventional radiological explorations in each subgroup of patients

| T2w- MRC | T2w-MRC and Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC | |

|---|---|---|

| Trauma groups (n = 20) | 0.312 | 0.040 |

| Postoperative and transplantation groups (n = 49) | 0.372 | 0.005 |

| Hydatid cyst groups (n = 30) | 0.443 | 0.001 |

P > 0.05 in the T2w-MRC group; P < 0.05 in the T2w-MRC and Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC group

Results

Ninety-nine patients with suspected biliary complications successfully underwent routine T2w-MRC and T1w CE-MRC using Gd-EOB-DTPA.

Biliary leak, confirmed by surgical exploration and interventional radiological procedures was found in 64 of the 99 patients (64.6 %; Table 2). Diagnostic accuracy of T2w-MRC alone and of combined images (CE-MRC and T2w-MRC) was shown in Tables 4 and 5 (P < 0.05).

Table 4.

Comparison between T2w-MRC and surgical or interventional exploration findings

| T2w-MRC | Surgical and interventional exploration findings | Sensitivitya (%) | Specificitya (%) | Accuracya (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP | TN | FP | FN | TP | TN | ||||

| Trauma group (n = 20) | 8 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 15 | 5 | 53.3 | 60 | 55 |

| Postoperative and transplantation group (n = 49) | 14 | 14 | 13 | 8 | 22 | 27 | 63.6 | 51.8 | 57.1 |

| Hydatid cyst group (n = 30) | 13 | 6 | 3 | 8 | 21 | 9 | 61.9 | 66.6 | 63.3 |

T2w-MRC T2-weighted magnetic resonance cholangiography, TP true-positive, TN true-negative, FP false-positive, FN false-negative

a Sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of T2-weighted MRC images

Table 5.

Comparison between combined imaging (Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced and routine T2w-MRC) and surgical and interventional exploration findings

| Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC and T2-weighted MRC | Surgical and interventional exploration findings | Sensitivitya (%) | Specificitya (%) | Accuracya (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP | TN | FP | FN | TP | TN | ||||

| Trauma group (n = 20) | 12 | 3 | - | 5 | 15 | 5 | 80 | 100 | 75 |

| Postoperative and Transplantation group (n = 49) | 19 | 24 | - | 6 | 22 | 27 | 76 | 100 | 91.4 |

| Hydatid cyst group (n = 30) | 19 | 7 | - | 4 | 21 | 9 | 82.6 | 100 | 86.6 |

T2w-MRC T2-weighted magnetic resonance cholangiography, TP true-positive, TN true-negative, FP false-positive, FN false-negative

a Sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of T2-weighted MRC images

Of 29 patients undergoing cholecystectomy and pancreaticoduodenectomy, 13 (44.8 %) showed abnormalities in the biliary tract, namely biliary fistulas (n = 6) and biliary leakage (n = 7). Combined routine T2w-MRC and CE-MRC images achieved to demonstrate extravasation in 11 of these patients (84.6 %; P < 0.05), whereas T2w-MRC failed to identify the abnormality in seven patients (false-negative rate, 53.8 %; Fig. 1a-c). Of six patients undergoing major liver resection, three (50 %) showed biliary extravasation: biliary fistulas (n = 2) and biliary leakage (n = 1). In two of these patients, the alteration was identified on combined T2w-MRC and Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC images (false-negative rate, 16 %, P < 0.05; Fig. 2a-c). Of 20 patients with traumatic biliary injury, 15 (75 %) showed bile extravasation: biliary leakage (n = 10) and biliary fistulas (n = 5). T2w-MRC diagnosed the abnormality in six (40 %) of these patients, whereas combined T2w-MRC and CE-MRC images detected the abnormality in 12 patients (80 %; P < 0.05; Fig. 3a, c). Of 14 patients who underwent orthotopic liver transplantation, six (42.8 %) had biliary extravasation: biliary leakage (n = 4) and biliary fistulas (n = 2). T2w-MRC images detected the abnormality in only two of these patients (33.3 %; Fig. 4a, b), whereas combined T2w-MRC and CE-MRC images delineated the alteration in four patients (66.7 %; P < 0.05; Fig. 5a-c).

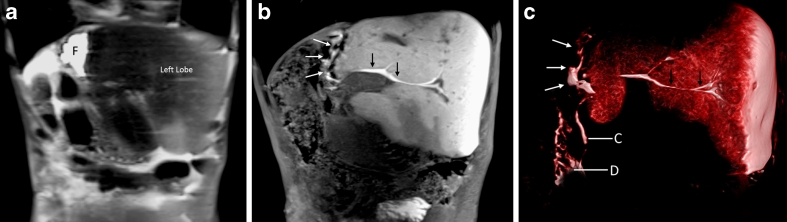

Fig. 1.

A 48-year-old woman with complication after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. T2w axial image (a) shows intraperitoneal free fluid (F) and hilar fluid collection (star), without possibility to discriminate its nature; coronal T2w-MRC HASTE sequence (b) allows the detection of an abrupt termination of the right (black arrow) and left main biliary ducts at the level of the hilar bifurcation with lack of visualisation of the common bile duct (white arrow); Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC image (c) shows the lack of contrast excretion in the left biliary tree and in the common bile duct and a suspected fistula from the right bile duct

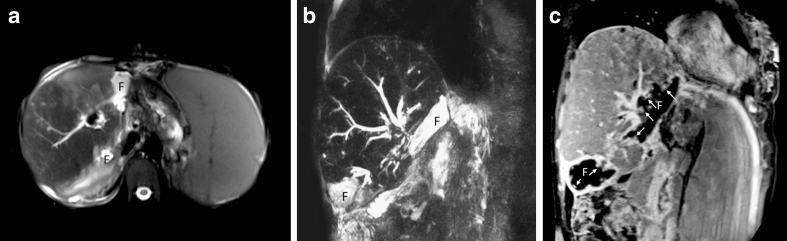

Fig. 2.

A 39-year-old man with complication after liver resection. T2w coronal image (a) shows loculated fluid collection (F) is detected in the surgical incision line; Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC image (b) shows the fluid collection is enhanced by the contrast agent (white arrows) indicating bile leakage (black arrow left bile duct); a 3D volume rendering reconstruction image (c) shows the bile leakage (white arrows). C common bile duct, D second segment of the duodenum

Fig. 3.

A 32-year-old man with complication after traumatic bile duct injury. T2w axial image (a) shows a fluid collection (star) in the liver parenchyma; T2w-MRC image (b) shows communication between the right posterior bile duct and the fluid collection (star); Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC image (c) shows bile leakage into the haematoma (star). The biliary leak was confirmed by surgical exploration

Fig. 4.

A 38-year-old man who had two anastomoses of the bile duct (right anterior and right posterior segmental ducts, separately) with complication after orthotopic liver transplantation. T2w-MRC image (a) shows fistula in both anastomosis lines (right anterior and posterior segmental ducts). The Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC image (b) shows occlusion of the bile duct that drains the right anterior lobe (arrowhead) of the liver and alteration of flow in the bile duct that drains the right posterior lobe (white arrow) of the liver

Fig. 5.

A 47-year-old man who presented with high fever due to complication after orthotopic liver transplantation. T2w axial image (a) image shows fluid collection in the hilum of the liver; T2w-MRC image (b) does not allow this collection to be distinguished from a biliary fistula or leakage; Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC image (c) shows that the fluid collection exhibits peripheral nodular contrast enhancement (arrows), indicating biliary fistula. F fluid collection

Of 21 patients who underwent surgical and interventional treatment for hydatid cyst, 19 (90.4 %) had cysto-biliary communication; combined T2w-MRC and CE-MRC images detected the abnormality in 17 of these patients (89.4 %; P < 0.05; Fig. 6a-c). Of nine patients who underwent percutaneous treatment of a hydatid cyst, eight (88.9 %) had cysto-biliary communication, and all were demonstrated by combined T2w-MRC and Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC images (P < 0.05; Fig. 7a-c).

Fig. 6.

A 41-year-old woman with complication of hydatid cyst treatment. T2w axial image (a) image shows type 3 hydatid cyst; T2w-MRC image (b) reveals cysto-biliary communication (arrows); Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC imaging (c) does not show any cysto-biliary communication

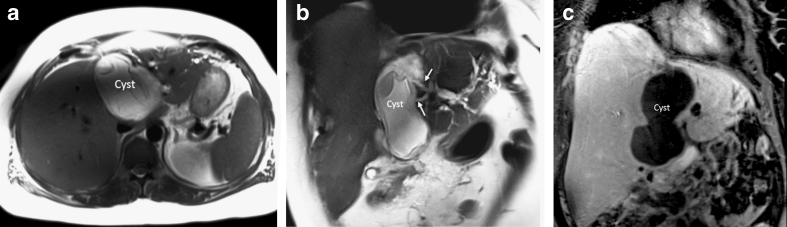

Fig. 7.

A 44-year-old man with complication of hydatid cyst treatment. T2w axial image (a) image shows type 2 hydatid cyst; T2w-MRC image (b) does not show any cysto-biliary communication; Gd-EOB-DTPA–enhanced MRC image (c) reveals cysto-biliary communication as peripheral nodular contrast-enhancement (arrows)

In five patients (20 %) treated with tube-drainage in hydatid cyst group, cysto-biliary communications were detected on post-contrast T1w- MRC 30–60 min after contrast agent administration. If visualisation of the biliary tree was insufficient, additional T1w-MRC images were obtained at 60, 120 and 180 min after contrast agent administration. In the remaining 25 patients with hydatid cyst, additional delayed MRC images from longer than 60 min after bolus administration of Gd-EOB-DTPA were obtained because visualisation of the bile ducts was not sufficient for anatomical diagnosis within 60 min of contrast agent administration. In 12 out of 25 patients (P < 0.05; 48 %) with a hydatid cyst, cysto-biliary communications were detected on T1w-MRC 180 min after contrast agent administration, as these alterations were not detected 60 min after contrast agent administration. At surgical exploration, additional cysto-biliary communications were detected in only four patients (16 %) who were missed on T1w-MRC 180 min after contrast agent administration. By Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced T1w-MRC, biloma collections in the gallbladder bed or perihepatic region were seen as peripheral nodular puddling similar to the pattern of contrast enhancement cavernous haemangioma (Fig. 7c). The accuracy of locating biliary leaks was superior using the combination of Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC and T2w-MRC for each group (Table 3).

Discussion

Our results show that the addition of Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC to standard T2w-MRC significantly increases the accuracy in detecting bile leaks. When we added the Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC images to the T2w-MRC, both observers by consensus performed better at identifying the presence of the bile extravasations.

Computed tomography, ultrasound, T2w-MRC, CE-MRC and PTC have been employed to identify bile leaks [13, 14]. However, surgical exploration remains the most reliable technique for detecting bile extravasation [15]. CE-MRC is a non-invasive diagnostic technique that does not require ionising radiation and it holds great potential for biliary imaging. Currently, the following three hepatobiliary contrast agents are available for CE-MRC: mangafodipir trisodium (Mn-DPDP, Teslascan; GE Healthcare, Oslo, Norway), gadobenate dimeglumine (Gd-BOPTA, MultiHance; Bracco Imaging, Milan, Italy) and gadolinium-ethoxybenzyl diethylenetriamine penta-acetic acid (Gd-EOB-DTPA, gadoxetic acid, Primovist; Bayer Schering Pharma, Berlin, Germany) [11]. Fayad et al. [4] used mangafodipir trisodium for CE-MRC to demonstrate bile extravasation. However, as Mn-DPDP is a purely hepatocyte-specific agent it only allows hepatobiliary phase imaging [16].

Unlike mangafodipir trisodium, Gd-EOB-DTPA and Gd-BOPTA allows both early dynamic and delayed hepatobiliary imaging [1, 2, 11–15, 17–20]. Intense enhancement of bile within the common bile duct has been reported to begin as early as 10 min after contrast material administration in healthy volunteers, and a 20-min delay after Gd-EOB-DTPA injection was reported to be sufficient for biliary evaluation [21–25]. Because Gd-EOB-DTPA uptake is mediated by the same transporter that is responsible for bilirubin transport, biliary obstruction or diminished hepatobiliary function can be suspected in patients with reduced or no visualisation of the biliary tree 20–30 min after Gd-EOB-DTPA administration [21, 26, 27]. In our study, hepatobiliary phase images were acquired 10, 20, 30, 60 and 180 min after contrast agent administration to minimise inter-individual differences in the circulation time.

Bile duct injuries are the most common and most serious complications associated with biliary surgery, especially laparoscopic cholecystectomy [28, 29]. Undiagnosed bile extravasation can be a significant cause of morbidity and mortality [30]. Traditionally, bile duct injuries have been classified by using the Bismuth or Strasberg classification. The Bismuth classification is based on the localisation of biliary strictures according to the distance from the biliary confluence but does not encompass the entire spectrum of bile duct injuries [31]. Therefore, Strasberg et al. [25] made the Bismuth classification much more comprehensive by including other types of laparoscopic extrahepatic bile duct injury (Table 6). Type A, a common form of bile duct injury, is seen after laparoscopic cholecystectomy and involves leakage from the cystic duct or the bile ducts of Luschka [24, 28, 32, 33]. Bile leaks usually manifest within the first postoperative week, whereas strictures without a bile leak tend to manifest several months to years after surgery [26]. Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC allows detection of active bile leakage by direct visualisation of contrast material extravasation into fluid collections in addition to demonstrating the anatomical site of the leakage and the type of bile duct injury. Extravasations of bile can be detected concretely on CE-MRC by their characteristic signs such as contrast-enhanced biloma and fistula formation [32–35]. Although only 8 of the 16 patients (50 %) with postoperative bile duct injuries were detected by T2w-MRC alone, the addition of Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC images to the T2w-MRC increased our detection to 13 of these 16 patients (81.2 %). Aduna et al. [15] detected postsurgical bile duct injuries on Mn-DPDP-enhanced MRC images with 95 % sensitivity and 100 % specificity respectively. Vitellas et al. [16] showed the presence of bile duct leaks after cholecystectomy on mangafodipir trisodium-enhanced MRC images with 86 % sensitivity and 83 % specificity respectively. In our study, the sensitivity and specificity of Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC images were 81.2 % and 100 % respectively for post-surgical biliary leaks.

Table 6.

Strasberg classification of bile duct injuries

| Type | Criteria |

|---|---|

| A | Leaks from the cystic duct or the bile ducts of Luschka |

| B | Occlusion of aberrant right hepatic ducts |

| C | Transection without ligation of aberrant right hepatic ducts |

| D | Lateral injuries to major bile ducts |

| E | Subdivided as per the Bismuth classification into E1–E5 |

Post-traumatic biliary tract injuries are also a significant cause of morbidity and mortality. Therefore, preoperative evaluation of biliary duct injury and biloma formation is very important for surgeons [28, 29, 32–34, 36]. In patients suspected of having a bile leak, cross-sectional imaging studies are useful for depicting fluid collection in the gallbladder bed or perihepatic region [30]. Concordantly, CE-MRC is also useful for assessing the degree of any obstruction according to the presence or absence of contrast material downstream in the bile duct [29, 35–37]. In patients with complete obstruction of the bile duct after trauma CE-MRC imaging shows proximal duct dilatation and lack of excretion of the contrast agent from the bile duct. Salvolini et al. [18] determined the traumatic biliary injuries on CE-MRC images, with 64 % sensitivity. In this study we detected 12 (80 % sensitivity) of the 15 patients with biliary injury. The injuries were accurately detected on the combined images (CE-MRC and T2w-MRC) before surgical treatment. Thus, post-traumatic morbidity and mortality were significantly decreased.

An obstruction is a relatively common complication of liver transplantation, occurring in up to 20 % of patients [36]. MRC depicts the site of the biliary anastomosis, the cause of the obstruction and the status of the biliary ducts upstream [37]. By using CE-MRC, comprehensive information on the patency of biliary-enteric anastomoses can be obtained [29, 36, 37]. In our study, four of the six patients (66 %) with biliary leakage after orthotopic liver transplantation were accurately detected on the combined images (CE-MRC and T2w-MRC), but biliary leakage in two of these patients was not detected on the routine T2w-MRC images. Fulcher and Turner [38] determined 19 of the 25 patients with ductal dilatation after liver transplantation on routine T2w-MRC images. CE-MRC imaging combined with T2w-MRC can be helpful in identifying biliary complications after liver transplantation.

In patients with a centrally located type 2 or 3 hepatic hydatid cyst larger than 10 cm, there is a higher risk of the cyst being close to the biliary tract [39]. Unless the relationship between the cyst and biliary tract is evaluated before endoscopic or percutaneous radiological procedures or surgery, alcohol-like scolicidal agents that are injected into the cyst may pass into biliary system, and cause chemical sclerotic reactions in the biliary tracts [16, 39]. Therefore, CE-MRC combined with T2w-MRC imaging plays a role in detecting a connection between the biliary duct and cyst when results of T2w-MRC are inconclusive or diagnostically insufficient [16, 29, 36, 37, 39]. Adaletli et al. [35] demonstrated a case with a fistulous communication between a hepatic hydatid cyst and the gallbladder on T2w-MRC images. In this study, 19 of the 21 patients (90.4 %) who had cysto-biliary communications were identified by Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC combined with T2w-MRC imaging before surgical and interventional radiological procedures. To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has investigated the added diagnostic value of CE-MRC in comparison to T2w-MRC in hepatic hydatid cysts.

Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC provides functional assessment of the biliary anatomy and detection of biliary leakage from other fluid collections. With CE-MRC, concrete evidence of contrast agent leakage from the biliary tract can be obtained, which is not possible with conventional MRC sequences [39–42]. Furthermore, we can evaluate bile duct injury, biliary-enteric anastomosis and sphincter of Oddi dysfunction; and differentiate biloma from other pathological conditions on Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC images [10]. At Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRC, filling defects might be masked if contrast material completely fills the bile duct, a pitfall similar to the one that occurs during ERCP (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography) due to overfilling or superimposition of contrast medium. Moreover, adequate contrast material filling in the bile duct requires liver function that is normal or at least not substantially reduced and a sufficient delay time [13]. As we had excluded the patients with increased total serum bilirubin over 17 mg/dl, we successfully evaluated the biliary tree on CE-MRC in our study. We should point out that the excretion of Gd-EOB-DTPA into the biliary tree interferes with successful visualisation of biliary fluid at conventional T2w-MRC, because at a higher concentration of the contrast material the signal intensity of bile appears darker on T2w images, owing to the T2-shortening effect of concentrated contrast material within the bile ducts [24]. Therefore, we acquired conventional T2w-MRC first in order to avoid the darkening effect of Gd-EOB-DTPA in the biliary tree.

Our study had a few limitations. Firstly, the patient population was relatively small. Our results will need to be confirmed by a larger prospective study. Secondly, two experienced radiologists performed image evaluation in consensus, and we did not determine interobserver variability. Because of the learning curve involved, it would have been better to assess interobserver agreement. Thirdly, the sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced were not calculated alone.

We conclude that CE-MRC using Gd-EOB-DTPA and the 3D GRE technique is a robust tool that displays the biliary anatomy and provides functional information about physiological or pathological biliary flow. The added diagnostic properties make it invaluable in the accurate detection of bile leaks and cysto-biliary communication. Therefore, CE-MRC can be added to T2w-MRC as a complementary tool in order to increase the accuracy in the detection of bile extravasations in selected patients.

References

- 1.Balci NC, Semelka RC. Contrast agents for MR imaging of the liver. Radiol Clin North Am. 2005;43:887–898. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewall DB, McCorkell SJ. Rupture of echinococcal cysts: diagnosis, classification, and clinical implications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1986;146:391–394. doi: 10.2214/ajr.146.2.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reimer P, Schneider G, Schima W. Hepatobiliary contrast agents for contrast-enhanced MRI of the liver: properties, clinical development and applications. Eur Radiol. 2004;14:559–578. doi: 10.1007/s00330-004-2236-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fayad LM, Holland GA, Bergin D, et al. Functional magnetic resonance cholangiography (fMRC) of the gallbladder and biliary tree with contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance cholangiography. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2003;18:449–460. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hammerstingl R, Huppertz A, Breuer J, et al. Diagnostic efficacy of gadoxetic acid (Primovist)-enhanced MRI and spiral CT for a therapeutic strategy: comparison with intraoperative and histopathologic findings in focal liver lesions. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:457–467. doi: 10.1007/s00330-007-0716-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ergen FB, Akata D, Sarikaya B, et al. Visualization of the biliary tract using gadobenate dimeglumine: preliminary findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2008;32:54–60. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e3180616b87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.An SK, Lee JM, Suh KS, et al. Gadobenate dimeglumine-enhanced liver MRI as the sole preoperative imaging technique: a prospective study of living liver donors. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:1223–1233. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.0584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheppard D, Allan L, Martin P, McLeay T, Milne W, Houston JG. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance cholangiography using mangafodipir compared with standard T2W MRC sequences: a pictorial essay. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;20:256–263. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fayad LM, Kamel IR, Mitchell DG, Bluemke DA. Functional MR cholangiography: diagnosis of functional abnormalities of the gallbladder and biliary tree. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:1563–1571. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.5.01841563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seale MK, Catalano OA, Saini S, Hahn PF, Sahani DV. Hepatobiliary-specific MR contrast agents: role in imaging the liver and biliary tree. Radiographics. 2009;29:1725–1748. doi: 10.1148/rg.296095515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karabulut N, Cakmak V, Kiter G. Confident diagnosis of bronchobiliary fistula using contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance cholangiography. Korean J Radiol. 2010;11:493–496. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2010.11.4.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bae K, Na JB, Choi DS, et al. Contrast-enhanced MR cholangiography: comparison of Gd-EOB-DTPA and Mn-DPDP in healthy volunteers. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:1250–1254. doi: 10.1259/bjr/22238911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Onur MR, Poyraz AK, Kocakoc E, Ogur E, Akyol M. Diagnosis of peritoneal metastases with abdominal malignancies: role of ADC measurement on diffusion weighted MRI. Eurasian J Med. 2012;44:163–168. doi: 10.5152/eajm.2012.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dahlstrom N, Persson A, Albiin N, Smedby O, Brismar TB. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance cholangiography with Gd-BOPTA and Gd-EOB-DTPA in healthy subjects. Acta Radiol. 2007;48:362–368. doi: 10.1080/02841850701196922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aduna M, Larena JA, Martin D, Martinez-Guereñu B, Aguirre I, Astigarraga E. Bile duct leaks after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: value of contrast-enhanced MRCP. Abdom Imaging. 2005;30:480–487. doi: 10.1007/s00261-004-0276-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vitellas KM, El-Dieb A, Vaswani KK, et al. Using contrast-enhanced MR cholangiography with IV mangafodipir trisodium (Teslascan) to evaluate bile duct leaks after cholecystectomy: a prospective study of 11 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:409–416. doi: 10.2214/ajr.179.2.1790409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee MS, Lee JY, Kim SH, et al. Gadoxetic acid disodium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging for biliary and vascular evaluations in preoperative living liver donors: comparison with gadobenate dimeglumine-enhanced MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;33:149–159. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salvolini L, Urbinati C, Valeri G, Ferrara C, Giovagnoni A. Contrast-enhanced MR cholangiography (MRCP) with GD-EOB-DTPA in evaluating biliary complications after surgery. Radiol Med. 2012;117:354–368. doi: 10.1007/s11547-011-0731-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hyodo T, Kumano S, Kushihata F, et al. CT and MR cholangiography: advantages and pitfalls in perioperative evaluation of biliary tree. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:887–896. doi: 10.1259/bjr/21209407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gandhi SN, Brown MA, Wong JG, Aguirre DA, Sirlin CB. MR contrast agents for liver imaging: what, when, how. Radiographics. 2006;26:1621–1636. doi: 10.1148/rg.266065014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tamada T, Ito K, Sone T, Kanki A, Sato T, Higashi H. Gd-EOB-DTPA enhanced MR imaging: evaluation of biliary and renal excretion in normal and cirrhotic livers. European J Radiol. 2010;80:207–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee NK, Kim S, Lee WJ, et al. Biliary MR imaging with Gd-EOB-DTPA and its clinical applications. Radiographics. 2009;29:1707–1724. doi: 10.1148/rg.296095501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tschirch FT, Struwe A, Petrowsky H, Kakales I, Marincek B, Weishaupt D. Contrast-enhanced MR cholangiography with Gd-EOB-DTPA in patients with liver cirrhosis: visualization of the biliary ducts in comparison with patients with normal liver parenchyma. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:1577–1586. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-0929-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kessel CS, Veldhuis WB, Bosch MAAJ, Leeuwen MS. MR liver imaging with Gd-EOB-DTPA: a delay time of 10 minutes is sufficient for lesion characterisation. Eur Radiol. 2012;22:2153–2160. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2486-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bollow M, Taupitz M, Hamm B, Staks T, Wolf KJ, Weinmann HJ. Gadoliniumethoxybenzyl-DTPA as a hepatobiliary contrast agent for use in MR cholangiography: results of an in vivo phase-I clinical evaluation. Eur Radiol. 1997;7:126–132. doi: 10.1007/s003300050125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strasberg SM, Hertl M, Soper NJ. An analysis of the problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;180:101–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Macera A, Lario C, Petracchini M, et al. Staging of colorectal liver metastases after preoperative chemotherapy. Diffusion-weighted imaging in combination with Gd-EOB-DTPA MRI sequences increases sensitivity and diagnostic accuracy. Eur Radiol. 2013;23:739–747. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2658-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papanikolaou N, Prassopoulos P, Eracleous E, Maris T, Gogas C, Gourtsoyiannis N. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance cholangiography versus heavily T2-weighted magnetic resonance cholangiography. Invest Radiol. 2001;36:682–686. doi: 10.1097/00004424-200111000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carlos RC, Hussain HK, Song JH, Francis IR. Gadolinium-ethoxybenzyl-diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid as an intrabiliary contrast agent: preliminary assessment. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:87–92. doi: 10.2214/ajr.179.1.1790087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pavone P, Laghi A, Catalano C, et al. MR cholangiography in the examination of patients with biliary-enteric anastomoses. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169:807–811. doi: 10.2214/ajr.169.3.9275901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ragozzino A, De Ritis R, Mosca A, et al. Value of MR Cholangiography in patients with iatrogenic bile duct injury after cholecystectomy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:1567–1572. doi: 10.2214/ajr.183.6.01831567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thurley PD, Dhingsa R. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: postoperative imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:794–801. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marin D, Bova V, Agnello F, et al. Gadoxetate disodium-enhanced magnetic resonance cholangiography for the noninvasive detection of an active bile duct leak after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2010;34:213–216. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e3181c1a72c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lau WY, Lai EC. Classification of iatrogenic bile duct injury. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2007;6:459–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adaletli I, Yilmaz S, Cakir Y, et al. Fistulous communication between a hepatic hydatid cyst and the gallbladder: diagnosis with MR cholangiopancreatography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:1211–1213. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prat F, Pelletier G, Ponchon T, et al. What role can endoscopy play in the management of biliary complications after laparoscopic cholecystectomy? Endoscopy. 1997;29:341–348. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1004213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Freeman ML, Overby C. Selective MRCP and CT targeted drainage of malignant hilar biliary obstruction with self-expanding metallic stents. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:41–49. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fulcher AS, Turner MA. Orthotopic liver transplantation: evaluation with MR cholangiography. Radiology. 1999;215:715–722. doi: 10.1148/radiology.211.3.r99jn17715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim HJ, Kim KW, Byun JH, et al. Comparison of mangafodipir trisodium and ferucarbotran enhanced MRI for detection and characterization of hepatic metastases in colorectal cancer patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:1059–1066. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Catalano OA, Singh AH, Uppot RN, Hahn PF, Ferrone CR, Sahani DV. Vascular and biliary variants in the liver: implications for liver surgery. Radiographics. 2008;28:359–378. doi: 10.1148/rg.282075099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsuda N, Okada M, Murakami T. New proposal for the staging of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: evaluation of liver fibrosis on Gd-EOB-DTPA enhanced MRI. Eur J Radiol. 2010;73:137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holzapfel K, Breitwieser C, Prinz C, et al. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance cholangiography using gadolinium-EOB-DTPA. Preliminary experience and clinical applications. Radiologe. 2007;47:536–544. doi: 10.1007/s00117-006-1444-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]