Abstract

Aims

The anticoagulant rivaroxaban is an oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor for the management of thromboembolic disorders. Metabolism and excretion involve cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) and 2J2 (CYP2J2), CYP-independent mechanisms, and P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and breast cancer resistance protein (Bcrp) (ABCG2).

Methods

The pharmacokinetic effects of substrates or inhibitors of CYP3A4, P-gp and Bcrp (ABCG2) on rivaroxaban were studied in healthy volunteers.

Results

Rivaroxaban did not interact with midazolam (CYP3A4 probe substrate). Exposure to rivaroxaban when co-administered with midazolam was slightly decreased by 11% (95% confidence interval [CI] −28%, 7%) compared with rivaroxaban alone. The following drugs moderately affected rivaroxaban exposure, but not to a clinically relevant extent: erythromycin (moderate CYP3A4/P-gp inhibitor; 34% increase [95% CI 23%, 46%]), clarithromycin (strong CYP3A4/moderate P-gp inhibitor; 54% increase [95% CI 44%, 64%]) and fluconazole (moderate CYP3A4, possible Bcrp [ABCG2] inhibitor; 42% increase [95% CI 29%, 56%]). A significant increase in rivaroxaban exposure was demonstrated with the strong CYP3A4, P-gp/Bcrp (ABCG2) inhibitors (and potential CYP2J2 inhibitors) ketoconazole (158% increase [95% CI 136%, 182%] for a 400 mg once daily dose) and ritonavir (153% increase [95% CI 134%, 174%]).

Conclusions

Results suggest that rivaroxaban may be co-administered with CYP3A4 and/or P-gp substrates/moderate inhibitors, but not with strong combined CYP3A4, P-gp and Bcrp (ABCG2) inhibitors (mainly comprising azole-antimycotics, apart from fluconazole, and HIV protease inhibitors), which are multi-pathway inhibitors of rivaroxaban clearance and elimination.

Keywords: cytochrome P450, drug interactions, healthy subjects, P-glycoprotein, rivaroxaban

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT

Rivaroxaban, an oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor, is metabolized and excreted via mechanisms involving CYP3A4/3A5/2J2, P-gp and Bcrp (ABCG2). However, the pharmacokinetic effects and implications of the co-administration of rivaroxaban and medications that interfere with these elimination pathways require characterization.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This paper reports on a series of interaction studies with rivaroxaban in healthy volunteers, the results of which suggest that rivaroxaban can be administered in conjunction with substrates or moderate inhibitors of CYP3A4 and/or P-gp without affecting its pharmacokinetic properties to a clinically relevant extent. However, strong inhibitors of CYP3A4, P-gp and Bcrp (ABCG2), such as azole-antimycotics and HIV protease inhibitors, cause a significant increase in rivaroxaban exposure that could increase the risk of bleeding. The exception is fluconazole, an azole-antimycotic, which interacted to a lesser degree and could, therefore, be co-administered with caution. The results of these studies provide important information to clinicians managing anticoagulation in patients who are taking concomitant medications.

Introduction

The oral anticoagulant rivaroxaban is a highly selective, direct Factor Xa inhibitor for the prevention and treatment of thromboembolic disorders. It inhibits human free and clot-bound Factor Xa (enzyme inhibition constant [Ki] 0.4 nm) independently of antithrombin [1]. In vitro, rivaroxaban has been shown to inhibit thrombin generation and prolong clotting times [1, 2]. Results of in vivo animal model studies showed that rivaroxaban was effective in the prevention and treatment of venous thrombosis [1, 3], as well as in the prevention of arterial thrombosis [1, 4], and this has been confirmed in humans in the RECORD [5], EINSTEIN [6, 7], ROCKET AF [8] and ATLAS ACS 2 TIMI 51 [9] phase III clinical trial programmes.

Rivaroxaban is approved for the prevention of venous thromboembolism (or deep vein thrombosis [DVT] that may lead to pulmonary embolism) after elective hip or knee replacement in adult patients in many countries [10, 11]. It has also been approved in the European Union and United States for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in adult patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation [10, 11], and in the European Union for the treatment of DVT and secondary prevention of DVT and pulmonary embolism after acute DVT [10].

Rivaroxaban has a dual mode of elimination. Approximately two-thirds of the administered dose undergoes metabolic degradation, with half eliminated renally and the remainder by the hepatobiliary route. The final one-third of the administered dose is eliminated via direct renal excretion as unchanged active substance in the urine, mainly via active renal secretion [12]. When comparing the renal clearance of rivaroxaban (approximately 30–40% of its apparent total body clearance [13, 14]) with normal glomerular filtration rate, taking into account the high plasma protein binding of rivaroxaban (approximately 92–95%), a considerable contribution of active secretion to renal elimination of this drug becomes evident [13]. In vitro investigations support the involvement of P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and breast cancer resistance protein (Bcrp [ABCG2]) as the responsible active renal transporters [15].

Rivaroxaban is metabolized via cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4/3A5, CYP2J2 and CYP-independent mechanisms [16, 17]. Oxidative degradation of the morpholinone moiety and hydrolysis of the amide bonds are the major pathways of biotransformation [18]. After a 10 mg oral dose of rivaroxaban, the metabolite profile in human plasma shows that unchanged rivaroxaban is the main compound, with no major or active circulating metabolites present [12]. With a systemic clearance of approximately 10 l h−1, rivaroxaban can be classified as a low clearance drug, lacking relevant presystemic first pass extraction [19, 20], with high absolute bioavailability (≥80% for the 10 mg dose) (unpublished data on file, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Wuppertal, Germany) [10]. Owing to the involvement of both CYP3A4 and CYP2J2 in rivaroxaban biotransformation and of transport proteins P-gp and Bcrp (ABCG2) in active renal secretion of rivaroxaban, it was important to determine the potential of rivaroxaban to interact with drugs that are substrates for, or known inhibitors of, these pathways.

In vitro studies showed that the active transport of rivaroxaban was unaffected by substrates of P-gp and Bcrp (ABCG2). However, these studies suggested that strong inhibitors of P-gp and/or Bcrp (ABCG2), such as ketoconazole and ritonavir, may reduce the renal clearance of rivaroxaban [15]. Further in vitro interaction studies showed that the biotransformation of rivaroxaban was affected by therapeutically relevant concentrations of ketoconazole and ritonavir, both of which are not only strong inhibitors of CYP3A4 [21, 22], but also potentially inhibitors of CYP2J2 [16, 17]. CYP3A4 substrates (including midazolam) or moderate to strong inhibitors of CYP3A4 only (erythromycin and clarithromycin) did not reveal any significant interactions (unpublished data on file, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Wuppertal, Germany). Using appropriate probe drugs and in vitro test systems, rivaroxaban itself (at concentrations up to more than 100-fold higher than therapeutic plasma concentrations) did not show any potential to induce or inhibit major CYP enzymes, including CYP3A4 or P-gp/Bcrp-mediated transport [10, 11, 15, 17], rendering clinically relevant interactions of rivaroxaban with co-medications unlikely. Clinically relevant drug–drug interactions between rivaroxaban and substrates of CYP enzymes are unlikely, because no significant influence of rivaroxaban on biotransformation reactions catalysed by relevant CYP isoforms was observed in vitro [17]. The likelihood of clinically relevant drug–drug interactions through induction of CYP1A2, 3A4, 2B6 or 2C19 was also considered to be very low [17].

This article reports the results of a series of mechanism-guided clinical drug–drug interaction studies in healthy subjects, in accordance with pertinent guidelines [23, 24], undertaken to determine the clinical extent of any potential interaction between rivaroxaban and substrates for, or inhibitors of, CYP3A4 and/or CYP2J2 and the transport proteins P-gp and Bcrp (ABCG2). Previously, rivaroxaban has demonstrated a lack of mutual interaction with the P-gp probe substrate digoxin [24, 25], as well as with the CYP3A4/P-gp substrate atorvastatin [26, 27]. Here, interaction studies were carried out between rivaroxaban and the following drugs:

A sensitive probe substrate for CYP3A4 only – midazolam [24, 28]

Strong inhibitors of CYP3A4 (and possibly CYP2J2), P-gp and Bcrp (ABCG2) – ketoconazole [24, 29, 30] and ritonavir [24, 29, 31]

A strong inhibitor of CYP3A4 and moderate inhibitor of P-gp – clarithromycin [24, 32]

A moderate inhibitor of CYP3A4 and P-gp – erythromycin [24, 33]

A moderate inhibitor of CYP3A4, also reported to potentially inhibit Bcrp (ABCG2) – fluconazole [24, 30]

Methods

In total, seven single centre studies were undertaken to determine the extent of potential interactions with single doses of rivaroxaban (10 mg or 20 mg) and steady-state ketoconazole (200 mg once daily), steady-state ritonavir (600 mg twice daily), steady-state clarithromycin (500 mg twice daily), steady-state erythromycin (500 mg three times daily), steady-state fluconazole (400 mg once daily) or a single dose of midazolam (7.5 mg). An additional study was undertaken to determine the extent of the possible interaction between steady-state rivaroxaban (10 mg once daily) and high dose, steady-state ketoconazole (400 mg once daily).

Healthy male subjects aged 18–55 years with a body mass index of 18–32 kg m−2 were enrolled into these studies. They were required to have a resting heart rate of 45–90 beats min−1, systolic blood pressure of 100–145 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure <95 mmHg and no relevant pathological changes in their electrocardiogram (ECG). Exclusion criteria included any clinically relevant condition (past or present) that may have interfered with the study, and any known coagulation disorders or disorders associated with an increased risk of bleeding.

Subjects were admitted to the study unit on the day prior to study drug administration. In the study investigating potential interactions between rivaroxaban and steady-state ketoconazole 200 mg, subjects received ketoconazole for 72 h as outpatients. Subjects were kept in-house for 72 h after administration of the study drugs alone, and were kept in-house for 92 h after administration of the drug combinations, except in the erythromycin interaction study, in which subjects were discharged 72 h after receiving the combination. Blood and urine samples were collected at regular intervals during the in-house periods, and at follow-up (up to 1 week after the last dose of study drug) for routine laboratory tests and to determine the pharmacokinetics of rivaroxaban and, where necessary, the pharmacokinetics of the potential interacting drug.

All studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonisation and Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and with the approval of the local ethics committee (North-Rhine Medical Council). Each subject gave their informed written consent.

Interaction study with a substrate of CYP3A4

Midazolam

A study was undertaken to determine potential interactions between rivaroxaban and a sensitive probe substrate for CYP3A4 alone, midazolam [24, 28].

In an open label, three way crossover study, subjects were randomized to receive a single dose of rivaroxaban 20 mg alone, a single dose of midazolam 7.5 mg alone or the combination. All study drugs were given under fasting conditions.

A total of 12 subjects were enrolled. Their mean age was 28.5 years (range 19–37 years) and their mean weight was 82.2 ± 11.2 kg. All subjects were included in the analyses of safety and pharmacokinetics.

Interaction studies with strong inhibitors of CYP3A4/2J2, P-gp and Bcrp (ABCG2)

Three studies were undertaken to determine the extent of the potential interaction between rivaroxaban and strong inhibitors of CYP3A4/2J2, P-gp and Bcrp (ABCG2), ketoconazole and ritonavir [24, 29, 30].

Ketoconazole

The initial ketoconazole interaction study investigated the potential interaction between a single dose of rivaroxaban and steady-state ketoconazole 200 mg once daily. In this open label, two way crossover study, subjects were randomized to receive a single dose of rivaroxaban 10 mg, alone or with ketoconazole (4 days of oral ketoconazole 200 mg once daily with rivaroxaban given on day 4). Rivaroxaban was given under fasting conditions and ketoconazole was given with food, except when co-administered with rivaroxaban. After completion of this study, a publication suggested that ketoconazole 400 mg may lead to higher inhibition of CYP 34, which prompted a second study investigating the maximum extent of the potential interaction between steady-state rivaroxaban and steady-state ketoconazole 400 mg once daily. This was a non-randomized, open label study in which subjects received oral rivaroxaban 10 mg once daily alone for 5 days, with concomitant ketoconazole 400 mg once daily for a further 5 days. All study drugs were administered with food.

In the ketoconazole 200 mg study, 12 subjects were enrolled. All completed the study and were included in the safety and pharmacokinetic analyses. Their mean age was 33 years (range 24–41 years) and their mean weight was 86.4 ± 9.2 kg. In the ketoconazole 400 mg study, a total of 20 subjects were enrolled. All completed the study and, therefore, were valid for the safety and pharmacokinetic analyses. Their mean age was 34.2 years (range 22–45 years) and their mean weight was 82.9 ± 10.9 kg.

Ritonavir

The potential interaction between a single dose of rivaroxaban and steady-state ritonavir was investigated in a non-randomized, open label study. Subjects received a single dose of rivaroxaban 10 mg on day 1, ritonavir 600 mg twice daily on days 3–7, and ritonavir 600 mg twice daily plus a single dose of rivaroxaban on day 8. All study drugs were administered with food.

Eighteen subjects were enrolled in the study. Their mean age was 33.2 years (range 18–44 years) and their mean weight was 84.3 ± 11.1 kg. One subject withdrew consent and one was withdrawn as a result of a protocol violation. However, neither subject had received the study drugs and so they were not valid for any analyses. As a result, 16 subjects were valid for the safety analysis. All received a single dose of rivaroxaban 10 mg on day 1 and at least one dose of ritonavir (600 mg). Twelve subjects received the combination of rivaroxaban and ritonavir on day 8. However, none of the subjects received the second dose of ritonavir on day 8 because of tolerability issues, which were considered to be related to ritonavir. Four subjects withdrew from the study owing to adverse events while receiving ritonavir alone (see below). Therefore, 12 subjects were valid for the pharmacokinetic analyses.

Interaction studies with other CYP3A4/P-gp inhibitors

Clarithromycin

A single study investigated the potential interaction between rivaroxaban and clarithromycin, classified as a strong inhibitor of CYP3A4, and considered to be a weak to moderate inhibitor of P-gp [24, 32].

In a randomized, two way crossover study, subjects were randomized to receive a single dose of rivaroxaban 10 mg alone, or clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily for a period of 4 days under steady-state conditions, followed by concomitant administration of both drugs on the morning of day 5. All study drugs were administered with food.

A total of 16 subjects were enrolled into the study, with a mean age of 37.6 years (range 24–50 years) and a mean weight of 81.1 ± 12.0 kg. One subject did not complete the study owing to an adverse event (ankle joint pain), and was included only for the safety analysis. The remaining 15 subjects were included in the pharmacokinetic analyses.

Erythromycin

A single study investigated the potential interaction between rivaroxaban and erythromycin, classified as a moderate inhibitor of CYP3A4, and considered to be a weak to moderate inhibitor of P-gp [24, 33].

In an open label, two way crossover study, subjects were randomized to receive a single dose of rivaroxaban 10 mg alone, or erythromycin 500 mg three times daily given for 4 days, with a single 500 mg dose given on day 5 with rivaroxaban 10 mg. All study drugs were administered with food and there was a 14 day washout period between study arms.

A total of 16 subjects were enrolled into the study and were valid for the safety analysis. Their mean age was 32.0 years (range 20–44 years) and their mean weight was 79.3 ± 11.2 kg. One subject withdrew from the study prematurely owing to an adverse event. Consequently, 15 subjects were valid for the pharmacokinetic analyses.

Fluconazole

A single study investigated the potential interaction between rivaroxaban and fluconazole, classified as a potent inhibitor of CYP2C9 (rivaroxaban is not metabolized via CYP2C9), a moderate inhibitor of CYP3A4, and also reported to potentially inhibit Bcrp (ABCG2) [24, 30].

In an open label, two way crossover study, subjects were randomized to receive a single dose of rivaroxaban 20 mg alone, or fluconazole 400 mg once daily given for 6 days, with a concomitant administration of 20 mg rivaroxaban given on day 5. All study drugs were administered with food and there was a 14 day washout period between study arms.

A total of 14 subjects were enrolled into the study, with a mean age of 33.8 years (range 24–53 years) and a mean weight of 83.7 ± 9.4 kg. One subject dropped out because of an adverse event before receiving any study medication. Consequently, 13 subjects received at least one dose of study medication and were included in both the safety and pharmacokinetic analyses.

Assessments and analyses

Safety

Safety and tolerability were assessed subjectively by spontaneous reporting of adverse events and questioning of subjects. Tolerability was evaluated by monitoring heart rate, blood pressure, ECG parameters, haematology and by analyzing clinical chemistry and urinalysis findings. Treatment-emergent adverse events were classified according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA).

Sample collection and analysis

Pharmacokinetic parameters were derived from rivaroxaban plasma concentration–time profiles obtained by serial blood sampling at predefined sampling time points in all studies. In addition, urine samples were collected during predefined time intervals after drug administration. Quantitative analysis of rivaroxaban concentrations (plasma and urine) was performed using a fully validated high performance liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry method after solid phase extraction, as described previously [35]. Across all studies, quality control plasma samples were determined with a lower limit of quantification of 0.5 μg l−1, an accuracy of 94.2–105.6% and a precision of 2.4–8.3%. Quality control urine samples were determined with a lower limit of quantification of 0.0997 mg l−1, an accuracy of 88.3–103.0% and a precision of 1.2–8.3% (ranges were narrower in the individual studies).

The following rivaroxaban plasma pharmacokinetic parameters were assessed: area under the plasma concentration–time curve (AUC(0,τ)) in the ketoconazole 400 mg study, in which multiple doses of rivaroxaban were given. Maximum drug concentration in plasma (Cmax), time to maximum drug plasma concentration (tmax) and elimination half-life (t1/2) were calculated using a model-independent (compartment free) method with the program WinNonlin® (Pharsight Corporation, Mountain View, CA, USA). The linear-logarithmic trapezoidal method was used to calculate AUC and t1/2 was derived by linear least-squares regression after logarithmic transformation of the terminal concentrations. Clearance of blood from plasma (CL/F) was calculated by dividing AUC by dose, and is considered to be close to total body clearance, because absolute bioavailability (F) for rivaroxaban is high (>80%) for the 10 mg dose [14] used in most of the studies. The amount of rivaroxaban excreted in the urine was used to determine the renal clearance (CLR). Non-renal (hepatic) clearance was defined as: CLNR = CL/F – CLR.

For mechanistic interpretation of the anticipated interaction findings (in the ketoconazole, ritonavir, clarithromycin, erythromycin and fluconazole studies), the fraction of free (unbound) drug in plasma (fu, %) for rivaroxaban was determined using equilibrium dialysis of total plasma concentrations at three predefined sampling time points. Creatinine clearance (CLcr), as a marker of glomerular filtration, was determined from serum creatinine measurements and urinary creatinine data collected in parallel to amount of rivaroxaban excreted in the urine. This allowed the splitting of rivaroxaban CLR into clearance by renal filtration (CLRF, calculated by CLCR × fu/100 [l h−1]) and clearance by active renal secretion (CLRS = CLR – CLRF [l h−1]). The AUC, Cmax, tmax and t1/2 of the potential interacting drugs were also assessed using fully validated assays and non-compartmental pharmacokinetic analyses, and reported in a descriptive manner, mainly for compliance but also to support a lack of interaction for co-medicated drugs, and to allow mechanistic drug–drug interaction modelling.

Pharmacokinetic parameters were assessed with either drug alone, and in combination with the potential interacting drug. In addition, as midazolam is metabolized by CYP3A4 to α-hydroxy-midazolam [28], the effect of rivaroxaban on the pharmacokinetics of this CYP3A4-mediated metabolite was also analyzed.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using an SAS software package. In the studies using a crossover design, the pharmacokinetic parameters AUC and Cmax of rivaroxaban were analyzed assuming log-normally distributed data. To compare the pharmacokinetics of rivaroxaban in the absence and presence of the potential interacting drug, the logarithms of the pharmacokinetic parameters were analyzed using analysis of variance (anova), including sequence, subject (sequence), period and study drug effects. Point estimates (least-squares means) and exploratory 90% confidence intervals (CIs) for the ratios were calculated by retransformation of the logarithmic results. The AUC and Cmax of midazolam (and its CYP3A4-mediated metabolites), in the absence or presence of rivaroxaban, were also analyzed using the same method.

In the ketoconazole 400 mg once daily and ritonavir studies, both using sequential designs, the pharmacokinetic parameters AUC and Cmax of rivaroxaban were analyzed assuming log-normally distributed data. Student's paired t-tests were used to analyze the differences in these parameters in the absence and presence of the potential interacting drug, and exploratory 90% CIs for the ratios were calculated by retransformation of the logarithmic results. Derived clearance values of rivaroxaban (CL/F, CLR, CLRS) were analyzed using the same methods.

Results

Interaction study with a substrate of CYP3A4

Midazolam

The pharmacokinetics of rivaroxaban, midazolam and its CYP3A4-mediated metabolite, α-hydroxy-midazolam, when rivaroxaban 20 mg and midazolam 7.5 mg were administered alone and in combination are summarized in Table 1. Co-administration with midazolam led to an increase in rivaroxaban median tmax from 1.5 h to 4.0 h and slightly decreased the rivaroxaban mean Cmax by 12% compared with rivaroxaban alone, a change that was not statistically significant (90% CI −28%, 7%). Rivaroxaban mean AUC remained almost unchanged. Co-administration with rivaroxaban slightly decreased the mean AUC of midazolam by 11% compared with midazolam alone, but this was not statistically significant (90% CI −25%, 5%). The mean Cmax was virtually unaffected. Conversely, the mean AUC of α-hydroxy-midazolam remained almost the same with co-administration of rivaroxaban and midazolam compared with midazolam alone, but the mean Cmax was increased by 11%. This change was not statistically significant (90% CI −23%, 59%). The tmax and t1/2 of midazolam and its metabolite remained similar in the presence or absence of rivaroxaban.

Table 1.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of rivaroxaban administered alone or in combination with midazolam 7.5 mg (mean/CV [range]) and comparison of pharmacokinetic characteristics between treatments based on anova results (point estimates and exploratory 90% CIs for the differences)

| Drug | AUC (μg l h−1) | Cmax (μg l−1) | tmax (h)1 | t1/2 (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacokinetic parameters of rivaroxaban (n = 12) | ||||

| Rivaroxaban (20 mg) | 1278/29.9 (881.0–2595) | 118.6/38.9 (70.1–232.0) | 1.5 (1.0–4.0) | 10.7/32.3 (6.4–18.8) |

| Rivaroxaban (20 mg) + midazolam (7.5 mg) | 1295/34.2 (732.3–2528) | 104.1/49.3 (38.6–258.9) | 4.0 (1.0–6.0) | 9.1/41.7 (4.4–17.8) |

| Ratio (90% CI) | 1.01 (0.92, 1.12) | 0.88 (0.72, 1.07) | ||

| Pharmacokinetic parameters of midazolam (n = 12) | ||||

| Midazolam (7.5 mg) | 97.8/38.6 (42.4–202.1) | 26.5/41.7 (12.8–51.9) | 1.5 (0.5–4.0) | 4.3/25.9 (2.3–5.8) |

| Rivaroxaban (20 mg) + midazolam (7.5 mg) | 86.9/52.2 (55.9–331.9) | 26.7/68.4 (11.4–80.8) | 1.5 (0.5–3.0) | 4.5/20.4 (3.1–5.7) |

| Ratio (90% CI) | 0.89 (0.75, 1.05) | 1.01 (0.73, 1.39) | ||

| Pharmacokinetic parameters of α-hydroxy-midazolam (n = 12) | ||||

| Midazolam (7.5 mg) | 29.0/34.6 (17.0–50.9) | 9.1/53.7 (4.6–18.5) | 1.1 (0.5–4.0) | 5.1/37.9 (3.0–10.0) |

| Rivaroxaban (20 mg) + midazolam (7.5 mg) | 28.6/36.1 (18.6–62.6) | 10.1/78.1 (4.2–35.2) | 1.0 (0.5–4.0) | 5.5/50.0 (2.9–13.6) |

| Ratio (90% CI) | 0.99 (0.85, 1.14) | 1.11 (0.77, 1.59) | ||

Median (range). anova, analysis of variance; AUC, area under the plasma concentration–time curve from zero to infinity after single (first) dose; CI, confidence interval; Cmax, maximum drug concentration in plasma after single dose administration; CV, coefficient of variation in %; t1/2, half-life associated with the terminal slope; tmax, time to reach maximum drug concentration in plasma after a single (first) dose.

Interaction studies with strong inhibitors of CYP3A4/2J2, P-gp and Bcrp (ABCG2)

Ketoconazole 200 mg once daily

The pharmacokinetic parameters of rivaroxaban 10 mg administered alone or in combination with ketoconazole 200 mg once daily are shown in Table 2. Co-administration with steady-state ketoconazole significantly increased the plasma concentrations of a single dose of rivaroxaban 10 mg compared with rivaroxaban alone. The mean AUC increased by 82% (90% CI 59%, 108%) and the mean Cmax increased by 53% (90% CI 27%, 85%). The total (apparent) body clearance of drug from plasma (CL/F) of rivaroxaban was significantly reduced by a mean of 45% (90% CI −52%, −37%) with combined vs. rivaroxaban alone.

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of rivaroxaban (10 mg) administered alone or in combination with ketoconazole 200 mg once daily or 400 mg once daily, ritonavir 600 mg twice daily, clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily, erythromycin 500 mg three times daily or fluconazole 400 mg once daily (mean/CV [range]), and comparison of pharmacokinetic characteristics between treatments based on anova results (point estimates and exploratory 90% CIs for the differences)

| Parameter | AUC (μg l h−1) | Cmax (μg l−1) | tmax (h)* | t1/2 (h) | CL/F (l h−1) | CLR (l h−1) | CLRS (l h−1) | fu (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ketoconazole | ||||||||

| Rivaroxaban 10 mg (n = 12) | 1088/17.4 (876.3–1441) | 148.8/28.2 (95.6–222) | 2.5 (0.8–6.0) | 7.3/50.4 (4.3–19.1) | 9.2/17.4 (6.9–11.4) | 3.2/17.9 (2.4–4.1) | – | – |

| Rivaroxaban 10 mg + ketoconazole 200 mg once daily (n = 12) | 1980/20.4 (1234–2481) | 228.1/21.5 (153.2–315) | 2.3 (0.8–3.0) | 5.7/21.8 (4.2–9.4) | 5.0/20.4 (4.0–8.1) | 2.1/30.3 (1.4–3.9) | – | – |

| Ratio (90% CI) | 1.82 (1.59, 2.08) | 1.53 (1.27, 1.85) | 0.55 (0.48, 0.63) | |||||

| Rivaroxaban 10 mg (n = 20) | 892/27.0 (557–1747) | 138.1/22.1 (86.2–219.2) | 3.0 (2–4) | 4.8/21.6 (3.3–7.8) | 11.2/27.0 (5.72–17.95) | 2.5/26.0 (1.6–5.0) | 1.9/29.9 (1.1–4.3) | 7.8/21.6 (4.8–10.4) |

| Rivaroxaban 10 mg + ketoconazole 400 mg once daily (n = 20) | 2298/26.0 (1501–3902)† | 237.0/20.1 (156.6–350) | 4.0 (3–8) | 6.5/24.5 (4.5–9.8) | 4.35/26.0 (2.56–6.66) | 1.6/33.1 (0.8–2.9) | 1.1/53.6 (0.3–2.4) | 7.5/29.5 (4.1–11.9) |

| Ratio (90% CI) | 2.58 (2.36, 2.82) | 1.72 (1.61, 1.83) | 0.39 (0.35, 0.42) | 0.56 (0.50, 0.68) | ||||

| Ritonavir | ||||||||

| Rivaroxaban 10 mg (n = 12) | 1000/16.1 (779–1170) | 153.7/15.4 (125–200) | 3.0 (2.0–4.0) | 5.7/31.0 (4.0–11) | 10.0/16.1 (8.5–13.0) | 4.0/20.0 (2.6–5.3) | 3.3/21.6 (2.3–4.7) | 7.0/27.0 (3.5–10.4) |

| Rivaroxaban 10 mg + ritonavir 600 mg twice daily (n = 12) | 2529/16.8 (1806–3370) | 238/23.4 (169.1–351) | 4.0 (0.5–8.0) | 6.9/31.4 (4.8–13.1) | 4.0/16.8 (3.0–5.5) | 1.0/47.3 (0.4–1.9) | 0.6/66.7 (0.2–1.3) | 7.3/19.6 (5.0–10.0) |

| Ratio (90% CI) | 2.53 (2.34, 2.74) | 1.55 (1.41, 1.69) | 0.40 (0.37, 0.43) | 0.18 (0.14, 0.24) | ||||

| Clarithromycin | ||||||||

| Rivaroxaban 10 mg (n = 15) | 964/22.1 (652.2–1517) | 139.4/16.3 (103.5–199) | 4.0 (1.0–6.0) | 6.7/39.0 (5.0–22.0) | 10.4/22.1 (6.6–15.3) | 3.8/31.0 (2.0–6.0) | 3.1/38.9 (1.3–5.1) | 10.6/16.5 (8.3–14.4) |

| Rivaroxaban 10 mg + clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily. (n = 15) | 1469/24.5 (905–2161) | 194.4/21.7 (122.5–284) | 4.0 (0.5–6.0) | 5.7/16.8 (4.0–7.2) | 6.8/24.5 (4.6–11.0) | 3.4/27.5 (1.9–4.7) | 2.8/31.9 (1.4–4.0) | 10.5/13.3 (7.4–12.3) |

| Ratio (90% CI) | 1.54 (1.44, 1.64) | 1.40 (1.30–1.52) | 0.65 (0.61, 0.69) | 0.90 (0.80, 1.01) | ||||

| Erythromycin | ||||||||

| Rivaroxaban 10 mg (n = 15) | 1069/30.5 (686–1666) | 170.5/29.6 (100.9–273.3) | 3.0 (0.5–4.0) | 7.0/44.2 (3.6–15.5) | 9.4/30.5 (6.0–14.6) | 3.0/39.3 (1.5–5.2) | 2.6/43.3 (1.3–4.7) | 6.7/21.7 (4.3–10.1) |

| Rivaroxaban 10 mg + erythromycin 500 mg three times daily (n = 15) | 1425/30.5 (629.4–2469) | 228.6/24.1 (143.8–380.1) | 3.0 (0.5–4.0) | 6.0/32.7 (4.0–10.5) | 7.0/30.4 (4.0–15.9) | 3.4/49.8 (0.9–9.4) | 2.8/60.1 (0.6–7.9) | 7.1/36.8 (4.2–14.8) |

| Ratio (90% CI) | 1.34 (1.23, 1.46) | 1.38 (1.21, 1.48) | 0.75 (0.69, 0.81) | 1.07 (0.90, 1.27) | ||||

| Fluconazole | ||||||||

| Rivaroxaban 20 mg (n = 13) | 1771/31.6 (887.4–2458) | 212.4/34.4 (83.03–318.2) | 4.0 (0.5–4.0) | 7.6/67.3 (4.1–26.3) | 11.3/31.6 (8.1–22.5) | 3.6/17.8 (2.5–4.7) | 2.8/20.8 (1.8–4.0) | 10.9/13.1 (8.3–13.0) |

| Rivaroxaban 20 mg + fluconazole 400 mg once daily (n = 13) | 2464/28.3 (1624–3612) | 268.8/21.1 (190.2–410.6) | 4.0 (0.5–4.0) | 9.5/58.0 (5.0–23.6) | 8.1/28.3 (5.5–12.3) | 3.0/17.6 (2.1–3.8) | 2.2/22.8 (1.3–3.1) | 10.3/14.1 (8.3–13.4) |

| Ratio (90% CI) | 1.42 (1.29, 1.56) | 1.28 (1.12, 1.47) | 0.71 (0.64, 0.78) | 0.78 (0.71, 0.86) | ||||

Median (range);

AUC(0,τ). AUC, area under the plasma concentration–time curve from zero to infinity after single (first) dose; AUC(0,τ), area under the plasma concentration–time curve for the actual dose interval; CI, confidence interval; CL/F, clearance of drug from plasma; CLR, renal body clearance of drug; CLRS, clearance by active renal secretion; Cmax, maximum drug concentration in plasma; CV, coefficient of variation in %; fu, fraction of free (unbound) drug in plasma; t1/2, half-life associated with the terminal slope; tmax, time to reach maximum drug concentration in plasma after a single (first) dose.

Ketoconazole 400 mg once daily

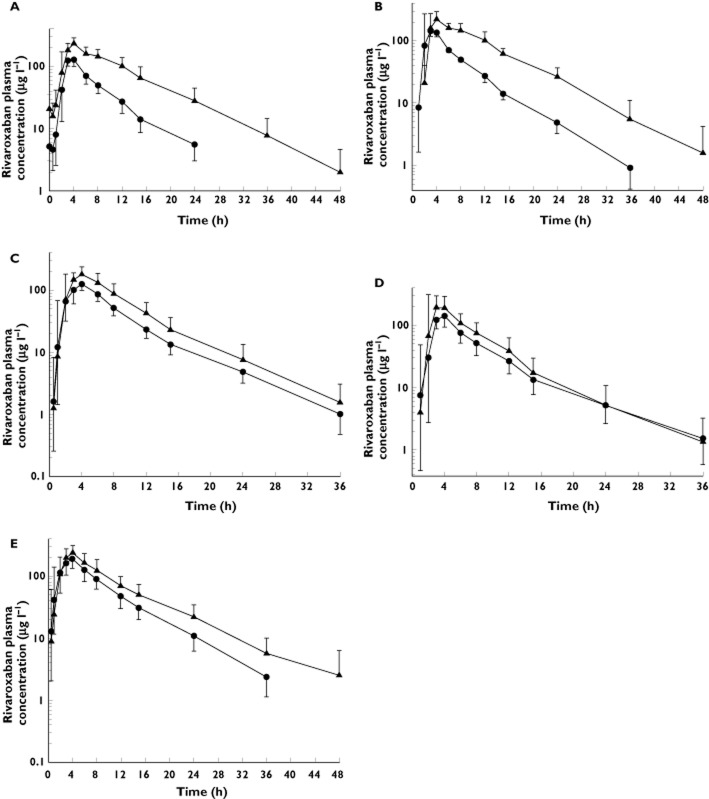

The pharmacokinetics of steady-state rivaroxaban 10 mg (day 5) were compared with those of steady-state rivaroxaban 10 mg in combination with steady-state ketoconazole 400 mg once daily (day 10). Co-administration with ketoconazole 400 mg significantly increased rivaroxaban plasma concentrations (Figure 1A). The mean AUC for the actual dose interval (AUCτ) was increased by 158% (90% CI 136%, 182%) and the mean Cmax by 72% (90% CI 61%, 83%) with the combination compared with rivaroxaban alone (Table 2). The mean CL/F was significantly decreased by 61% (90% CI −65%, −58%) with the combination of drugs, and clearance by active renal secretion (CLRS) was also significantly reduced by a mean of 44% (90% CI −50%, −32%).

Figure 1.

Plasma concentration–time profile of rivaroxaban (20 mg [fluconazole study] or 10 mg [all other studies] once daily) in the absence and presence of (A) steady-state ketoconazole (400 mg once daily given concomitantly for 5 days),  , rivaroxaban alone (n = 20);

, rivaroxaban alone (n = 20);  , rivaroxaban + ketoconazole (n = 20); (B) steady-state ritonavir (600 mg twice daily for 8 days),

, rivaroxaban + ketoconazole (n = 20); (B) steady-state ritonavir (600 mg twice daily for 8 days),  , rivaroxaban alone (n = 12);

, rivaroxaban alone (n = 12);  , rivaroxaban + ritonavir (n = 12); (C) steady-state clarithromycin (500 mg twice daily for 4 days),

, rivaroxaban + ritonavir (n = 12); (C) steady-state clarithromycin (500 mg twice daily for 4 days),  , rivaroxaban alone (n = 15);

, rivaroxaban alone (n = 15);  , rivaroxaban + clarithromycin (n = 15); (D) steady-state erythromycin (500 mg three times daily for 5 days),

, rivaroxaban + clarithromycin (n = 15); (D) steady-state erythromycin (500 mg three times daily for 5 days),  , rivaroxaban alone (n = 15);

, rivaroxaban alone (n = 15);  , rivaroxaban + erythromycin (n = 15); (E) steady-state fluconazole (400 mg once daily for 6 days),

, rivaroxaban + erythromycin (n = 15); (E) steady-state fluconazole (400 mg once daily for 6 days),  , rivaroxaban alone (n = 13);

, rivaroxaban alone (n = 13);  , rivaroxaban + fluconazole (n = 13)

, rivaroxaban + fluconazole (n = 13)

Ritonavir

The pharmacokinetics of rivaroxaban 10 mg were compared after a single dose (day 1) with those of a single dose of steady-state ritonavir 600 mg twice daily (day 8). In addition, the pharmacokinetics of ritonavir were compared in the absence and presence of rivaroxaban (days 7 and 8, respectively). Steady-state ritonavir significantly increased the AUC and Cmax of rivaroxaban. The mean AUC increased by 153% (90% CI 134%, 174%) and the mean Cmax increased by 55% (90% CI 41%, 69%) compared with rivaroxaban alone (Table 2). Mean plasma concentrations of rivaroxaban were shown to increase with the combined regimen (Figure 1B). Ritonavir significantly decreased the CL/F of rivaroxaban by 60% (90% CI −63%, −57%) without affecting the fu of rivaroxaban. CLRS was significantly reduced by 82% (90% CI −86%, −76%).

Interaction studies with other CYP3A4/P-gp inhibitors

Clarithromycin

The pharmacokinetics of rivaroxaban were compared after a single dose of rivaroxaban 10 mg was administered alone and co-administered with clarithromycin 500 mg after 4 days of pretreatment with clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily. Co-administration with clarithromycin significantly increased the primary pharmacokinetic parameters of rivaroxaban (Table 2, Figure 1C). Both the mean AUC and Cmax were significantly increased, by 54% (90% CI 44%, 64%) and 40% (90% CI 30%, 52%), respectively, in comparison with rivaroxaban alone. Co-administration significantly decreased the mean CL/F of rivaroxaban from plasma by 35% (90% CI −39%, −31%), whereas mean CLRS was not significantly reduced (10% decrease; 90% CI −20%, 1%).

Erythromycin

The pharmacokinetic effects of rivaroxaban 10 mg administered alone (day 5) and in combination with steady-state erythromycin (500 mg three times daily for 4 days with a single 500 mg dose on day 5) were analyzed. Co-administration with steady-state erythromycin significantly increased the pharmacokinetics of rivaroxaban (Table 2, Figure 1D). The mean AUC and Cmax both significantly increased (by 34% [90% CI 23%, 46%] and 38% [90% CI 21%, 48%], respectively) compared with rivaroxaban alone. The mean CL/F of rivaroxaban was significantly decreased by 25% (90% CI −31%, −19%) with the combination. However, CLRS was not significantly affected (increased by 7%; 90% CI −10%, 27%) and the fu of rivaroxaban showed a slight increase of 6%.

Fluconazole

The pharmacokinetics of rivaroxaban were compared after a single dose of rivaroxaban 20 mg was administered alone and co-administered with fluconazole 400 mg after 4 days of pretreatment with fluconazole 400 mg once daily. Co-administration with fluconazole significantly increased the primary pharmacokinetic parameters of rivaroxaban (Table 2, Figure 1E). Both the mean AUC and mean Cmax increased (by 42% [90% CI 29%, 56%] and 28% [90% CI 12%, 47%], respectively) in comparison with rivaroxaban alone. Co-administration significantly decreased the CL/F of rivaroxaban from plasma by 29% (90% CI −36%, −22%) and significantly reduced CLRS by 22% (90% CI −29%, −14%).

Tolerability and adverse events across all studies

In these studies, most adverse events reported were mild or moderate in intensity and resolved by the end of the study. A total of 64 events, none of which was serious, were considered to be possibly related to rivaroxaban alone or a combination involving rivaroxaban. Of these, headache (32 events) and fatigue (13 events) were the most common. No clinically relevant changes in ECG or vital signs were observed. Subjects taking ritonavir exhibited adverse events consistent with its established safety profile.

Discussion

The results of these specific interaction studies in healthy subjects demonstrate that rivaroxaban does not interact with a probe substrate for CYP3A4 (midazolam). Co-administration of rivaroxaban with a moderate CYP3A4 and P-gp inhibitor (erythromycin), a moderate inhibitor of CYP3A4 and potentially Bcrp (ABCG2, fluconazole), and a strong inhibitor of CYP3A4 and moderate inhibitor of P-gp (clarithromycin), led to a statistically significant increase in rivaroxaban exposure. Of note, active renal secretion (CLRS) was reduced to a moderate but statistically significant extent with fluconazole but minimally with erythromycin and clarithromycin. As expected from in vitro studies [15, 24, 29, 30], a pronounced and statistically significant interaction was demonstrated between rivaroxaban and strong inhibitors of CYP3A4 (and possibly CYP2J2), P-gp and Bcrp (ABCG2, ketoconazole and ritonavir).

The co-administration of rivaroxaban with midazolam had no effect on the pharmacokinetics of rivaroxaban, or on the pharmacokinetics of midazolam or its CYP3A4-mediated metabolites. Previous interaction studies with digoxin (a pure P-gp substrate with a narrow therapeutic window) and atorvastatin (a substrate of both CYP3A4 and P-gp) in healthy subjects demonstrated no effect on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of rivaroxaban, or on the pharmacokinetics of digoxin or atorvastatin [25, 27]. This lack of interaction confirms previous in vitro observations that rivaroxaban does not induce or inhibit any major CYP isoforms, including CYP3A4, or P-gp/Bcrp transporters [10, 11, 15, 17]. This information is of further value because the concomitant use of rivaroxaban and these drugs is highly likely. Rivaroxaban is now in use for the prevention of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation, and phase III data for secondary prevention in patients with acute coronary syndrome have been published. Patients with these conditions are likely to be taking concomitant cardiovascular medications, such as digoxin and statins [36, 37].

The co-administration of rivaroxaban and the frequently used antibiotic erythromycin, a moderate CYP inhibitor and weak to moderate P-gp inhibitor, led to a 34% and 38% increase in the AUC and Cmax of rivaroxaban, respectively. However, as with other studies reporting similar statistically significant increases and/or decreases in these parameters when drugs were co-administered with erythromycin [38, 39], these changes were not considered to be clinically relevant because they were similar in magnitude to the inter-individual variability expected for rivaroxaban in patients [20, 40]. The decreased clearance and slightly increased active renal secretion of rivaroxaban when it was co-administered with steady-state erythromycin may be partially explained by the observed mean difference in CLcr between the treatment periods (CLcr is a key factor in the formulae used to derive clearance by renal filtration [CLRF] and CLRS). The interaction between rivaroxaban and another frequently used antibiotic, clarithromycin, classified as a strong inhibitor of CYP3A4 only, but reported also to possess weak to moderate P-gp inhibitory potential, was also moderate (mean increases of 54% and 40% in rivaroxaban AUC and Cmax, respectively), with a minimal decrease in active renal secretion.

These results, combined with in vitro data [15, 17], suggest that rivaroxaban has the potential to interact to a clinically relevant extent with strong inhibitors of both CYP3A4 and the transport proteins P-gp and Bcrp (ABCG2). This was confirmed in the studies with ketoconazole and ritonavir, both strong inhibitors of CYP3A4 (and possibly CYP2J2 based on in vitro data [unpublished data on file, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Wuppertal, Germany]), P-gp and Bcrp (ABCG2). There were significant increases in exposure to rivaroxaban when it was co-administered with ketoconazole and ritonavir, with a more than two-fold increase in the AUC. Ketoconazole 400 mg led to an approximately 70% mean inhibition of non-renal (metabolic) clearance of rivaroxaban (derived from data in Table 2) and a 44% mean inhibition of active renal secretion, whereas ritonavir led to a reduction of metabolic clearance by approximately 50% and of active renal secretion by more than 80%. It is anticipated that similar interactions will occur with other members of the same drug class (i.e. azole-antimycotics and HIV protease inhibitors, respectively) and, as a result, the concomitant administration of rivaroxaban with these drugs should be avoided because of a potential increase in the risk of bleeding [10, 11]. An exception may be the azole-antimycotic fluconazole, which is classified as a strong CYP2C9 inhibitor with only moderate inhibitory potential for CYP3A4. In the present study, the quantitative assumption for the interaction of fluconazole with rivaroxaban was moderate (mean increases of 42% and 28% in rivaroxaban AUC and Cmax, respectively).

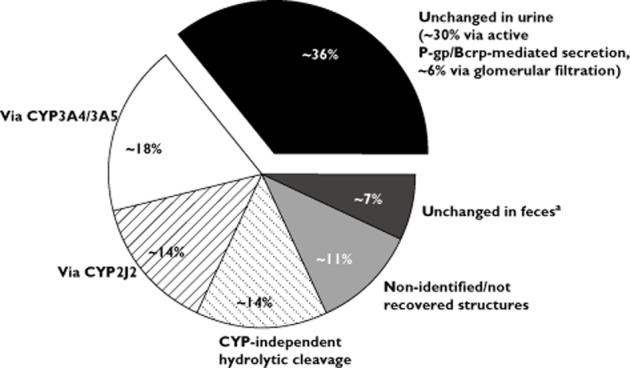

Based on excretion and metabolite data derived from studies in humans [12, 13] and the results from the in vitro CYP-reaction phenotyping study [16–18], the clearance pathways of rivaroxaban have been quantified to the following average values. The contribution of CYP3A4/3A5 accounts for approximately 18% and CYP2J2 for approximately 14% of total rivaroxaban elimination. In addition to this oxidative biotransformation, non-CYP-mediated hydrolysis of the amide bonds (approximately 14%) and active, transporter-mediated (P-gp, Bcrp [ABCG2]) renal excretion of unchanged drug (approximately 30%; total renal excretion of unchanged drug: 36% [13]) play important roles as elimination pathways (Figure 2). The results of all previously reported interaction studies are in accordance with the contributions of the respective routes of rivaroxaban multi-pathway clearance and the inhibitory potential of the specific inhibitors employed [23, 24]. This confirms both the established mechanistic understanding of the clearance and elimination profile for rivaroxaban and its potential for drug–drug interactions when linking in vitro and in vivo data. Of note, although the studies described here involve single doses of rivaroxaban, no relevant accumulation was observed in a multiple dose escalation study [41]. This indicates that the concentrations of rivaroxaban observed after single dose administration can be considered representative for steady-state conditions.

Figure 2.

Metabolic clearance and elimination pathways of rivaroxaban based on in vitro investigations [16–18] and human studies [12, 13]. All numbers are approximate. aPotentially not absorbed

In conclusion, CYP3A4, CYP2J2 and the transport proteins P-gp and Bcrp (ABCG2), are involved in the elimination of rivaroxaban. Therefore, it was important to determine the clinical extent of any potential interaction between rivaroxaban and drugs that are substrates for and/or inhibitors of these pathways. The results of these studies suggest that the oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor rivaroxaban does not interact to a clinically relevant extent with substrates for, or inhibitors of, CYP3A4 and/or P-gp, unless the agent strongly inhibits both CYP3A4 and P-gp/Bcrp (ABCG2). The latter group essentially comprises two classes of drugs, the azole-antimycotics and the HIV protease inhibitors. Therefore, the concomitant use of rivaroxaban with these agents should be avoided. The exception may be fluconazole, which is expected to have less effect on rivaroxaban exposure and can be co-administered with caution [10, 11].

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research funding from Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals and Janssen Research & Development, LLC. We wish to acknowledge Stephen Purver, who provided medical writing services with funding from Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals.

Competing Interests

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare that all authors are employees of Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals and for all authors, there are no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the design, conduct and interpretation of one or more of the studies described in this manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and contributed to its content.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site:

Appendix S1

Additional information on experimental methodology

References

- 1.Perzborn E, Strassburger J, Wilmen A, Pohlmann J, Roehrig S, Schlemmer KH, Straub A. In vitro and in vivo studies of the novel antithrombotic agent BAY 59-7939 – an oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:514–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerotziafas GT, Elalamy I, Depasse F, Perzborn E, Samama MM. In vitro inhibition of thrombin generation, after tissue factor pathway activation, by the oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor rivaroxaban. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:886–888. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biemond BJ, Perzborn E, Friederich PW, Levi M, Buetehorn U, Büller HR. Prevention and treatment of experimental thrombosis in rabbits with rivaroxaban (BAY 59-7939) – an oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor. Thromb Haemost. 2007;97:471–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perzborn E, Arndt B, Harwardt M, Lange U, Fischer E, Trabant A. Antithrombotic efficacy of BAY 59-7939 – an oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor – compared with fondaparinux in animal arterial thrombosis and thromboembolic death models. Eur Heart J. 2005;26(Suppl):Abstract P2943. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turpie AGG, Lassen MR, Eriksson BI, Gent M, Berkowitz SD, Misselwitz F, Bandel TJ, Homering M, Westermeier T, Kakkar AK. Rivaroxaban for the prevention of venous thromboembolism after hip or knee arthroplasty. Pooled analysis of four studies. Thromb Haemost. 2011;105:444–453. doi: 10.1160/TH10-09-0601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The EINSTEIN Investigators. Oral rivaroxaban for symptomatic venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2499–2510. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The EINSTEIN–PE Investigators. Oral rivaroxaban for the treatment of symptomatic pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1287–1297. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, Pan G, Singer DE, Hacke W, Breithardt G, Halperin JL, Hankey GJ, Piccini JP, Becker RC, Nessel CC, Paolini JF, Berkowitz SD, Fox KAA, Califf RM ROCKET AF Investigators. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:883–891. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mega JL, Braunwald E, Wiviott SD, Bassand JP, Bhatt DL, Bode C, Burton P, Cohen M, Cook-Bruns N, Fox KA, Goto S, Murphy SA, Plotnikov AN, Schneider D, Sun X, Verheugt FW, Gibson CM. Rivaroxaban in patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:9–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xarelto® (rivaroxaban) Bayer Pharma AG Summary of Product Characteristics. 2012. Available at http://www.xarelto.com/html/downloads/Xarelto-Prescribing_Information-Nov-2012.pdf (last accessed 11 December 2012)

- 11.Xarelto® (rivaroxaban) Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc Prescribing Information. 2012. Available at http://www.xareltohcp.com/sites/default/files/pdf/xarelto_0.pdf (last accessed 11 December 2012)

- 12.Weinz C, Schwarz T, Kubitza D, Mueck W, Lang D. Metabolism and excretion of rivaroxaban, an oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor, in rats, dogs and humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:1056–1064. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.025569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kubitza D, Becka M, Mueck W, Halabi A, Maatouk H, Klause N, Lufft V, Wand DD, Philipp T, Bruck H. Effects of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and safety of rivaroxaban, an oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;70:703–712. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03753.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kubitza D, Becka M, Voith B, Zuehlsdorf M, Wensing G. Safety, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics of single doses of BAY 59-7939, an oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;78:412–421. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gnoth MJ, Buetehorn U, Muenster U, Schwarz T, Sandmann S. In vitro and in vivo P-glycoprotein transport characteristics of rivaroxaban. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;338:372–380. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.180240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cardiovascular and Renal Drugs Advisory Committee. FDA Advisory Committee Briefing Document. 2009. Available at http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/CardiovascularandRenalDrugsAdvisoryCommittee/UCM181524.pdf (last accessed 13 December 2012)

- 17.European Medicines Agency. CHMP assessment report for Xarelto EMEA/543519/2008. 2008. Available at http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Public_assessment_report/human/000944/WC500057122.pdf (last accessed 13 December 2012)

- 18.Lang D, Freudenberger C, Weinz C. In vitro metabolism of rivaroxaban – an oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor – in liver microsomes and hepatocytes of rat, dog and man. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:1046–1055. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.025551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mueck W, Becka M, Kubitza D, Voith B, Zuehlsdorf M. Population model of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of rivaroxaban – an oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor – in healthy subjects. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;45:335–344. doi: 10.5414/cpp45335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mueck W, Eriksson BI, Bauer KA, Borris L, Dahl OE, Fisher WD, Gent M, Haas S, Huisman MV, Kakkar AK, Kälebo P, Kwong LM, Misselwitz F, Turpie AGG. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of rivaroxaban – an oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor – in patients undergoing major orthopaedic surgery. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2008;47:203–216. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200847030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.von Moltke LL, Greenblatt DJ, Grassi JM, Granda BW, Duan SX, Fogelman SM, Daily JP, Harmatz JS, Shader RI. Protease inhibitors as inhibitors of human cytochromes P450: high risk associated with ritonavir. J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;38:106–111. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1998.tb04398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang JS, Wen X, Backman JT, Taavitsainen P, Neuvonen PJ, Kivisto KT. Midazolam alpha-hydroxylation by human liver microsomes in vitro: inhibition by calcium channel blockers, itraconazole and ketoconazole. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1999;85:157–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1999.tb00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products (CPMP) Note for guidance on the investigation of drug interactions CPMP/EWP/560/95. 1997. Available at http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500002966.pdf (last accessed 13 December 2012)

- 24.Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry. Drug interaction studies – study design, data analysis, implications for dosing, and labeling recommendations. Draft Guidance 2012. Available at http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM292362.pdf (last accessed 13 December 2012)

- 25.Kubitza D, Becka M, Zuehlsdorf M, Mueck W. No interaction between the novel, oral direct Factor Xa inhibitor BAY 59-7939 and digoxin. J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;46:Abstract 11. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holtzman CW, Wiggins BS, Spinler SA. Role of P-glycoprotein in statin drug interactions. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26:1601–1607. doi: 10.1592/phco.26.11.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kubitza D, Mueck W, Becka M. No interaction between rivaroxaban – a novel, oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor – and atorvastatin. Pathophysiol Haemost Thromb. 2008;36:Abstract P062. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kronbach T, Mathys D, Umeno M, Gonzalez FJ, Meyer UA. Oxidation of midazolam and triazolam by human liver cytochrome P450IIIA4. Mol Pharmacol. 1989;36:89–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mao Q, Unadkat JD. Role of the breast cancer resistance protein (ABCG2) in drug transport. AAPS J. 2005;7:E118–E133. doi: 10.1208/aapsj070112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta A, Unadkat JD, Mao Q. Interactions of azole antifungal agents with the human breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) J Pharm Sci. 2007;96:3226–3235. doi: 10.1002/jps.20963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gupta A, Zhang Y, Unadkat JD, Mao Q. HIV protease inhibitors are inhibitors but not substrates of the human breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2) J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;310:334–341. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.065342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wakasugi H, Yano I, Ito T, Hashida T, Futami T, Nohara R, Sasayama S, Inui K. Effect of clarithromycin on renal excretion of digoxin: interaction with P-glycoprotein. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998;64:123–128. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(98)90030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim RB, Wandel C, Leake B, Cvetkovic M, Fromm MF, Dempsey PJ, Roden MM, Belas F, Chaudhary AK, Roden DM, Wood AJ, Wilkinson GR. Interrelationship between substrates and inhibitors of human CYP3A and P-glycoprotein. Pharm Res. 1999;16:408–414. doi: 10.1023/a:1018877803319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao P, Ragueneau-Majlessi I, Zhang L, Strong JM, Reynolds KS, Levy RH, Thummel KE, Huang SM. Quantitative evaluation of pharmacokinetic inhibition of CYP3A substrates by ketoconazole: a simulation study. J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;49:351–359. doi: 10.1177/0091270008331196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rohde G. Determination of rivaroxaban – a novel, oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor – in human plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2008;872:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2008.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gheorghiade M, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Colucci WS. Contemporary use of digoxin in the management of cardiovascular disorders. Circulation. 2006;113:2556–2564. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.560110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumar A, Cannon CP. Importance of intensive lipid lowering in acute coronary syndrome and percutaneous coronary intervention. J Interv Cardiol. 2007;20:447–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2007.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cooper KJ, Martin PD, Dane AL, Warwick MJ, Raza A, Schneck DW. The effect of erythromycin on the pharmacokinetics of rosuvastatin. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;59:51–56. doi: 10.1007/s00228-003-0573-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luurila H, Olkkola KT, Neuvonen PJ. Interaction between erythromycin and nitrazepam in healthy volunteers. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1995;76:255–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1995.tb00139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mueck W, Lensing AW, Agnelli G, Decousus H, Prandoni P, Misselwitz F. Rivaroxaban: population pharmacokinetic analyses in patients treated for acute deep-vein thrombosis and exposure simulations in patients with atrial fibrillation treated for stroke prevention. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2011;50:675–686. doi: 10.2165/11595320-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kubitza D, Becka M, Wensing G, Voith B, Zuehlsdorf M. Safety, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics of BAY 59-7939 – an oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor – after multiple dosing in healthy male subjects. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;61:873–880. doi: 10.1007/s00228-005-0043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.