Abstract

In this Letter, we describe a short, high yielding protocol for the enantioselective (87–96% ee) and general synthesis of β-fluoroamines and previously difficult to access γ-fluoroamines from commercial aldehydes via organocatalysis.

Keywords: β-fluoroamine, γ-fluoroamine, Enantioselective, Organocatalysis

Small molecule probes and drug candidates that contain one or more chiral fluorine atoms are commonplace and represent a critical component of the medicinal chemists’ toolbox.1,2 In the context of amine-containing ligands, introduction of a fluorine atom either β- or γ- to the amine often maintains activity at the desired target while providing a 1–2 log reduction in pKa. That shift in electronic structure often results in diminished ancillary pharmacology at cardiac ion channels, improved metabolic stability, enhanced pharmacokinetics, and increased CNS penetration.1–3 In some cases, introduction of a chiral β-fluoroamine, due to the almost 2-log impact on pKa, can diminish activity at the desired target; however, moving the fluorine atom to the γ-position has been shown to maintain the desired bioactivity, while still affording the benefits of the β-fluoroamine congeners.1–6

While we and others have made considerable advances in the synthesis of chiral β-fluoroamines,7–13 the synthesis of γ-congeners still relies on classical DAST approaches which are plagued with rearranged and dehydrated products.1–6,14 Therefore, new synthetic strategies to access these elusive, chiral γ-fluoroamines were warranted.

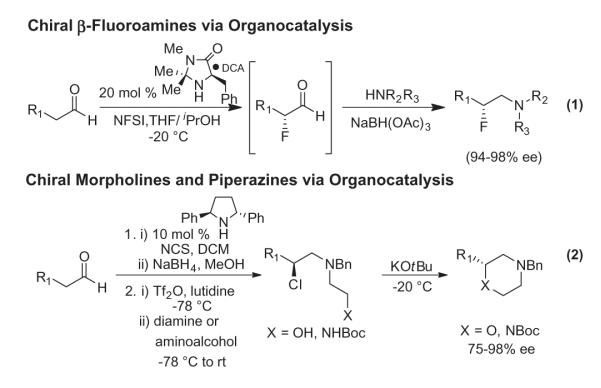

Previous work from our lab (Fig. 1) employed a one-pot protocol to access chiral β-fluoroamines via organocatalysis in high yield and % ee (Eq. 1); however, the configurational instability of the incipient α-fluoroaldehyde required its immediate conversion to the β-fluoroamine.7,8 Later efforts utilized a similar strategy, but employed the analogous α-chloroaldehydes, to access chiral N-terminal aziridines15 and chiral morpholines and piperazines;16 however, the configurational instability of the α-chloroaldehyde also necessitated immediate, one-pot use. To provide additional flexibility, we developed an approach (Fig. 1, Eq. 2) that improved yields and % ee for the synthesis of chiral morpholines and piperazines by reducing the α-chloroaldehyde to an alcohol, converting the hydroxyl to a leaving group, displacing the leaving group with an amino alcohol or diamine followed by base-induced cyclization.16,17

Figure 1.

First generation organocatalytic approach to chiral β-fluoroamines and refined approach to chiral morpholines and piperazines.

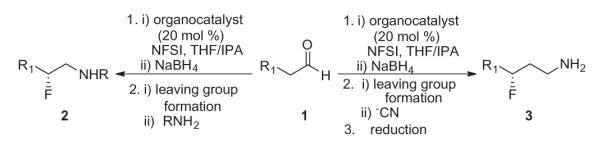

These results led us to reflect on the β- and γ-fluoroamine problem, and apply this strategy to their asymmetric construction (Fig. 2). Here, we envisioned standard organocatalytic α-fluorination followed by reduction to the β-fluoroalcohol to provide a bench stable, chiral intermediate. Conversion of the hydroxyl to a leaving group followed by SN2 displacement with an amine would provide chiral β-fluoroamines 2, whereas a cyanide displacement, followed by nitrile reduction, would afford rapid access to chiral γ-fluoroamines 3.

Figure 2.

Envisioned route to access both chiral β- and γ-fluoroamines via organocatalysis.

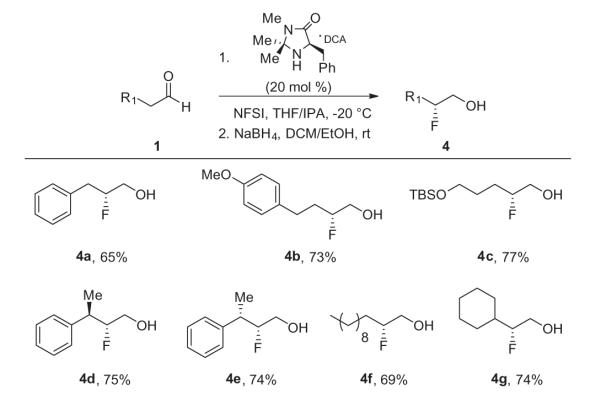

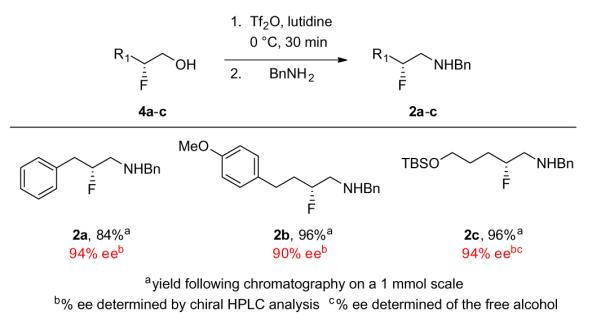

To validate this new approach, we prepared a number of β-fluoroalcohol substrates 4a–g under standard conditions in good yields (65–77%) and high enantioselectivity (87–96% ee) as expected from literature precedent (Scheme 1).7,8,18–20 Conversion to the corresponding triflate, and displacement with benzylamine delivered the desired chiral β-fluoroamines 2a–c (Scheme 2) in high yields (84–96%) and in excellent enantioselectivity (90–94% ee). In essence, this new strategy sets the key stereocenter in a conformationally stabile way, affording the β-fluoroamines with reproducibly high % ee, and higher yields than the first generation chiral β-fluoroamine route.7

Scheme 1.

Organocatalytic, enantioselective synthesis of β-fluoroalcohols 4a–g.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of chiral β-fluoroamines 2a–c.

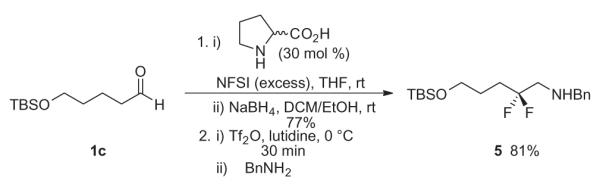

In some instances, a β,β-difluoroamines have been shown to be an important pharmacophore,1–7 and we wanted to determine if this new approach would grant access to this moiety as well. Here (Scheme 3), organocatalytic α-fluorination with excess NFSI leads to α,α-difluorination, and reduction affords the β,β-difluoroalcohol. Conversion to the triflate and displacement with benzylamine provides the desired β,β-difluoroamine 5 from the difluoroalcohol in 81% yield, representing another improvement over our first generation methodology.7

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of a β,β-difluoroamine 5.

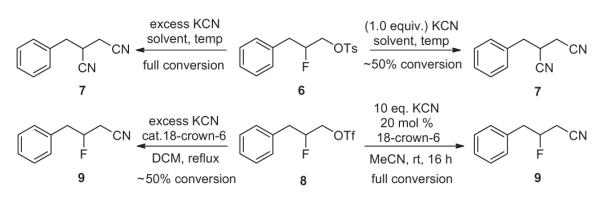

While the ability to access β-fluoroamines was gratifying, our main objective with this approach was to gain access to chiral γ-fluoroamines, a chemotype that is very challenging to prepare in high enantioselectivity.1–8,14 We began our attempts with a racemic 4a congener and surveyed a variety of leaving groups for cyanide displacement en route to γ-fluoroamines. Interestingly, when tosylate 6 was employed, all attempts (independent of cyanide source, stoichiometry, solvent, and temperature) afforded a 1,2-bis-cyano adduct 7 (Scheme 4). As more forcing conditions were required for tosylate displacement, a competing displacement of the fluoride by cyanide occurred. When triflate 8 was used, excess KCN in refluxing DCM provided the desired β-fluoronitrile 9, but in only 50% conversion accompanied by considerable decomposition. Further surveying of reaction conditions and refinement led to the discovery of optimal conditions (10 equiv KCN in the presence of 20 mol % 18-crown-6 at room temperature in MeCN for 16 h) to fully convert triflate 8 to the desired fluoronitrile 9, without any evidence of cyanide displacement of the fluoride.

Scheme 4.

Optimization of β-fluoronitrile 8 synthesis.

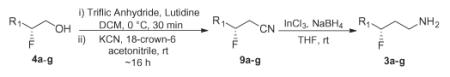

With racemic 9 in hand, we then evaluated a number of reducing agents to provide the γ-fluoroamine. Interestingly, the vast majority of common methods for nitrile reduction (LiAlH4, DIBALH, H2/Pd, Ni(0)/NaBH4) failed to reduce the β-fluoronitrile without considerable decomposition or defluorination. Ultimately, good results were obtained with the milder conditions of InCl3/NaBH4,21,22 delivering the γ-fluoroamines in yields up to 90%.

Having developed a route to racemic γ-fluoroamines, attention was now directed at accessing chiral γ-fluoroamines, an elusive and difficult to prepare pharmacophore. Here, the chiral β-fluoroalcohols 4a–g (Scheme 1) were converted into the corresponding triflates, which were then displaced under the optimized cyanide displacement conditions to deliver chiral β-fluoronitriles 9a–g in yields ranging from 71% to 93% (Table 1). Our optimized reduction protocol with InCl3/NaBH4 smoothly provided the chiral γ-fluoroamines 3a–g in excellent yields (73–90%) and enantioselectivity (87–96% ee). The overall yields starting from commercial aldehydes 1 range from 40–58%. Of particular utility of this approach is the commercial availability of both enantiomers of the organocatalyst, enabling either enantiomer of the chiral γ-fluoroamine to be prepared. We were now able to access chiral β-fluoro- and γ-fluoroamines, as well as β,β-difluoroamines, providing a range of finely tuned amine basicity (with pKas of 10.7 (parent amine) to 9.0 (β-fluoro), to 7.3 (β,β-difluoro) to 9.7 (γ-fluoro)). Attempts to prepare a γ,γ-difluoro congener, to provide an amine substrate with a pKa of ~8.7 failed, as we were unable to displace the β,β-difluorotriflate with cyanide in yield greater than 10%, despite surveying a broad spectrum of reaction conditions (cyanide source, temperature, solvent, additives).23

Table 1.

Chrial γ-fluoroamines 10a–g via organocatalysis

| Starting material | Yield of 9a–ga | Yield of 3a–gb | % eec |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4a | 9a, 71% | 3a, 87% | 94% |

| 4b | 9b, 92% | 3b, 84% | 87% |

| 4c | 9c, 73% | 3c, 86% | 92% |

| 4d | 9d, 93% | 3d, 83% | 96% |

| 4e | 9e, 77% | 3e, 90% | 96% |

| 4f | 9f, 82% | 3f, 89% | 95% |

| 4g | 9g, 84% | 3g, 73% | 96% |

All reactions were performed on a 1.0 mmol scale.

All reactions were performed on a 0.5 mmol scale.

Enantiomeric excess determined by 19F NMR using the (R)-Mosher amide of the final amine.

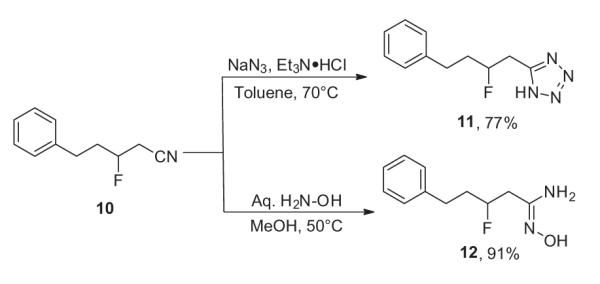

By synthesizing β-fluoronitriles, we envisioned them not only as precursors to γ-fluoroamines, but also as intermediates poised to access a variety of fluorinated scaffolds using the nitrile as a handle. To illustrate this idea, we performed common reactions to exemplify the β-fluoronitrile as a lynchpin providing access to other, difficult to prepare, fluorinated moieties. As seen in Scheme 5, the β-fluoronitrile 10 was used in a [3+2] cycloaddition with sodium azide to provide β-fluorotetrazole 11, a common carboxylic acid bioisostere.24 Additionally, hydrolysis of the nitrile with hydroxylamine provided amide oxime 12, a precursor for oxadiazole synthesis.25 Overall, the chiral β-fluoronitrile linchpin offers rapid entry to a wide range of valuable fluorinated functional groups with subtle perturbations of pKa and electronic properties.

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of a β-fluoro tetrazole and a β-fluoro amide oxime.

In summary, we have developed a powerful extension of our one-pot, chiral β-fluoroamine work, that overcomes issues related to variable % ee due to configurationally unstable α-fluoroaldehydes, by a two-pot protocol that affords β-fluoroamines in high yields and reproducibly high enantioselectivity (90–94% ee). A further extension allows access to highly elusive and previously difficult to prepare chiral γ-fluoroamines using a three-pot protocol in good overall yields (40–58%) and excellent enantioselectivities (87–96%) from commercial aldehydes. Importantly, outside of classical DAST chemistry, this work represents the only other approach for the enantioselective synthesis of γ-fluoroamines, an important pharmacophore in drug discovery and development. Moreover, the chiral β-fluoronitrile linchpin offers rapid access to a wide range of valuable fluorinated functional groups with subtle perturbations of pKa and electronic properties. Additional refinements are under development and will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding from the Department of Pharmacology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center and the Warren Family & Foundation for funding the William K. Warren, Jr. Chair in Medicine.

Footnotes

Supplementary data Supplementary data (experimental details and characterization data for all new compounds) associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tetlet.2013.04.116.

References and notes

- 1.Hagmann WK. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:4359–4369. doi: 10.1021/jm800219f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Purser S, Morre PR, Swallow S, Gouverance V. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008;37:320–330. doi: 10.1039/b610213c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Hagan D. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008;37:308–319. doi: 10.1039/b711844a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rowley M, Hallett DJ, Goodacre S, Moyes C, Crawforth J, Sparey TJ, Patel S, Marwood R, Patel S, Thomas S, Hitzel L, O’Connor D, Szeto N, Castro JL, Hutson PH, Macleod AM. J. Med. Chem. 2001;44:1603–1612. doi: 10.1021/jm0004998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang Z-Q, Barrow JC, Shipe WD, Schlegel KS, Shu Y, Yang FV, Lindsley CW, Rittle KE, Bock MG, Hartman GD, Uebele VN, Nuss CE, Fox SV, Kraus RL, Doran SM, Connolly TM, Tang C, Ballard JE, Kuo Y, Adarayan ED, Prueksaritanont Y, Zrada MM, Marino MJ, DiLella AG, Reynolds IJ, Vargas HM, Bunting PB, Woltman MM, Koblan KS, Renger JJ. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:6471–6477. doi: 10.1021/jm800830n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shipe WD, Barrow JC, Yang Z-Q, Lindsley CW, Yang FV, Schlegel KS, Shu Y, Rittle KE, Zrada MM, Bock MG, Hartman GD, Tang C, Ballard JE, Kuo Y, Adarayan ED, Prueksaritanont Y, Uebele VN, Nuss CE, Connolly TM, Doran SM, Fox SV, Kraus RL, Marino MJ, Graufelds VK, Vargas HM, Bunting PB, Hasbun-Manning M, Evans RM, Koblan KS, Renger JJ. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:3692–3695. doi: 10.1021/jm800419w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fadeyi OO, Lindsley CW, Org CW. Lett. 2009;11:943–946. doi: 10.1021/ol802930q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schulte ML, Lindsley CW, Org CW. Lett. 2011;13:5684–5687. doi: 10.1021/ol202415j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Creswell AJ, Davies SG, Lee JA, Roberts PM, Russell AJ, Thomson JE, Tyte MJ. Org. Lett. 2010;12:2936–2939. doi: 10.1021/ol100862s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duggan PJ, Johnston M, March TL. J. Org. Chem. 2010;75:7365–7372. doi: 10.1021/jo101600c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Appayee C, Brenner-Moyer SE. Org. Lett. 2010;12:3356–3359. doi: 10.1021/ol101167z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malamakal RM, Hess WR, Davis TA. Org. Lett. 2010;12:2186–2189. doi: 10.1021/ol100647b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalow JA, Schmitt DE, Doyle AG. J. Org. Chem. 2012;77:4177–4183. doi: 10.1021/jo300433a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Percy JM. Sci. Synth. 2005;34:379–416. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fadeyi OO, Schulte ML, Lindsley CW. Org. Lett. 2010;12:3276–3278. doi: 10.1021/ol101276x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Reilly MC, Lindsley CW. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012;53:1539–1542. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.12.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Reilly MC, Lindsley CW. Org. Lett. 2012;14:2910–2913. doi: 10.1021/ol301203z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beeson TD, MacMillan DWC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:8826–8828. doi: 10.1021/ja051805f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halland N, Braunton A, Bachmann S, Margio M, Jorgensen KA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:4790–4791. doi: 10.1021/ja049231m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Margio M, Bachmann S, Halland N, Braunton A, Jorgensen KA. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004;43:5507–5511. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saavedra JZ, Resendez A, Rovira A, Eagon S, Haddenham D, Singaram B. J. Org. Chem. 2012;77:221–228. doi: 10.1021/jo201809a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Souza MVN, Vasconcelos TRA. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2006;20:798–810. [Google Scholar]

- 23.See supporting information for listing of attempted conditions for synthesizing β,β-difluoronitriles.

- 24.Koguro K, Oga T, Mitsui S, Orito R. Synthesis. 1998;6:910–914. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Copp RR, Abraham BD, Farnham JG, Twose TM. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2011;15:1344–1347. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.