Abstract

Bacillus spp. are well known rhizosphere residents of many crops and usually show plant growth promoting (PGP) activities that include biocontrol capacity against some phytopatogenic fungi. Potato crops in the Andean Highlands of Peru face many nutritional and phytophatogenic problems that have a significant impact on production. In this context is important to investigate the natural presence of these microorganisms in the potato rhizosphere and propose a selective screening to find promising PGP strains. In this study, sixty three Bacillus strains isolated from the rhizosphere of native potato varieties growing in the Andean highlands of Peru were screened for in vitro antagonism against Rhizoctonia solani and Fusarium solani. A high prevalence (68%) of antagonists against R. solani was found. Ninety one percent of those strains also inhibited the growth of F. solani. The antagonistic strains were also tested for other plant growth promotion activities. Eighty one percent produced some level of the auxin indole-3-acetic acid, and 58% solubilized tricalcium phosphate. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that the majority of the strains belonged to the B. amyloliquefaciens species, while strains Bac17M11, Bac20M1 and Bac20M2 may correspond to a putative new Bacillus species. The results suggested that the rhizosphere of native potatoes growing in their natural habitat in the Andes is a rich source of Bacillus fungal antagonists, which have a potential to be used in the future as PGP inoculants to improve potato crop.

Keywords: Bacillus, plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria, potato, antagonism, phosphate solubilization, 16S rRNA gene.

INTRODUCTION

Potato is a staple crop in 130 countries worldwide, ranking fourth in production after rice, maize, and wheat. This important crop was domesticated by pre-Columbian civilizations in the Andean highlands of Peru and Bolivia. Nowadays, the yield levels of potato crop in subsistence agriculture in the Andes are low to medium, ranging between 5 to 8 t ha-1 for low input systems and 15 to 20 t ha-1 for high input systems, indicating a low soil fertility and a low nutrient availability (11). Also, fungal diseases affect crop yield and tubers quality. Black scurf and dry rot caused by Rhizoctonia solani and Fusarium solani, respectively, are among the most common potato fungal diseases in the Andes (31).

The use of beneficial microorganisms could be an environmentally sound option to increase crop yields and reduce disease incidence. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) colonize plant roots and induce an increase in plant growth (33). Among the mechanisms by which PGPR exert beneficial effects on plants are facilitating the uptake of nutrients such as phosphorus via phosphate solubilization, synthesizing stimulatory phytohormones like indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) (33), or aiding in the control of the deleterious effects of pathogens by producing inhibitory substances, excluding them from the roots by competition or by inducing systemic resistance (7).

Strains of the genus Bacillus are among the most commonly reported PGPR (7, 33). The secondary metabolites produced by certain species and strains of Bacillus have antibacterial or antifungal activity against phytopathogenic microorganisms (2, 7). Products for plant disease biocontrol containing B. subtilis and other Bacillus species have being used over the past years as seed dressings in several crops (26). Bacillus strains have the advantage of being able to form endospores which confers them high stability as biofungicides or biofertilizers (26).

Exotic strains from commercial inoculants may not survive in local soils due to different edaphic or climatic conditions, or be out-competed by better adapted native bacteria during plant colonization resulting in poor performance of PGPR (4, 18). Therefore, isolation and screening of native strains is justified. Bacillus strains have been previously isolated from potato rhizospheres (5, 28) but nothing is known about the Bacillus strains associated with potato growing in its domestication Andean areas. The aims of this study were (i) to screen for native rhizospheric Bacillus showing in vitro antagonism against R. solani and F. solani and other plant growth promoting activities, and (iii) to determine the phylogenetic affiliation of some representative selected isolates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacillus strains

Sixty three Bacillus strains previously isolated from the rhizosphere of native varieties of potato (Solanum tuberosum) growing in Huancavelica and Puno, two Andean regions of Peru, were used (6). Strains were grown in TGE agar (composition per liter: triptone 5 g, glucose 10 g, beef extract 3 g, agar 15 g) at 28 °C. Pure cultures were kept at 4 °C in TGE agar slants and at -80 °C in 15% glycerol. B. amyloliquefaciens FZB24, a known antagonist of phytopathogenic fungi and IAA producer, was used as control in several tests (17). The lecithinase test was used to discard any strains putatively belonging to the potentially pathogenic Bacillus cereus species. The production of lecithinase was assayed by observing the formation of a white precipitate around colonies after streaking on MEYP (Mannitol-Egg Yolk-Polymixin) agar, where the majority of strains of B. cereus give a positive reaction (14).

In vitro screening for antagonism

One pathogenic strain of Rhizoctonia solani and one of Fusarium solani were isolated in this work from sick tubers obtained in a potato field located in Huancavelica. For R. solani, the tubers were disinfected with sodium hypochlorite (1,5%) for one minute, the sclerotia were retired and place in water agar and PDA (Potato Dextrose Agar) plates. For F. solani, the white characteristic mycelium of affected tubers was retired and placed on water agar and PDA plates. The plates were incubated at 20 °C for 7–10 d. After purification, the fungi were identified in the International Potato Center’s Phytopathology Laboratory by microscopic observation of characteristic structures (3), namely, the anatomy of the septal pore and the cellular nuclear number for R. solani (1), and the macroconidia and microconidia produced in the aerial mycelium for F. solani (23).

Antagonistic activity was tested using the dual culture technique (16). Briefly, three 5 μl drops of each bacterial culture (108 cfu ml-1) were equidistantly placed on the margins of potato dextrose agar plates adjusted to pH 7. A one cm agar disc from a fresh culture of R. solani or F. solani was placed at the center of the plate. Control plates not inoculated with bacteria were also prepared. Plates were incubated at 20 °C for 5 d (R. solani) or 7 d (F. solani). The fungal growth inhibition was quantified by using the percentage inhibition formula: ((R-r) × R-1 × 100), where, r is the radius of the fungal colony that grew towards the bacterial colony and R is the maximum radius of the fungal colony away from the bacterial colony (the maximum growth that the fungi can have in the Petri dish) (16). Two independent experiments with each bacterial isolate replicated two times were performed.

Production of IAA

The Salkowski reagent (0.01 M FeCl3 in 36% H2SO4) was used to colorimetrically assay the production of IAA (12, 13). Isolates were grown in TGE supplemented with 5 mM of L-tryptophan with agitation (150 rpm) at 28 ºC for 4 d. 300 μl of the Salkowski reagent was added to 100 μl of cultures in a microplate. After 15 minutes in the dark, color reaction was visually scored. The results were expressed in an arbitrary scale of color intensity. Non inoculated and untreated controls were kept for comparison. The experiment was independently performed twice with two replicates of the bacterial strains each time.

Assay for phosphate solubilization

Phosphate solubilization test was conducted by plating 5 μl of bacterial cultures (108 ufc ml-1) in NBRIP (National Botanical Research Institute's phosphate growth medium) agar that contains insoluble tricalcium phosphate making the medium opaque (22). The solubilization halo was calculated by subtracting colony diameter from the total diameter. Measures were taken every 2 d during a 30 d period. Two independent experiments with each bacterial isolate replicated two times were performed.

Correlation analysis

The correlation between the different plant growth promoting characteristics was determined by calculating Pearson product moment correlation coefficients (36). The correlations were considered significant if P < 0.05.

DNA techniques and phylogenetic analysis

Total DNA was extracted from liquid cultures with the GenomicPrep kit (Amersham) using the manufacturer's instructions. BOX genomic fingerprints were generated as described by Versalovic et al. (32). DNA fragments were separated in a 3% agarose gel, photograped after ethidium bromide staining, and the bands visually recorded. Different BOX profiles were assigned to strains having at least one different band. 16S rRNA genes were PCR amplified using primers fD1 and rD1 (35) and sequenced. The sequences of type- and reference strains of related Bacillus species (34) were identified by BLASTN searches. Phylogenetic analysis was performed by the neighbor joining (NJ) method with genetic distances computed with the Kimura’s two-parameter model using Mega4 (30, 34). The sequences determined in this study have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers FJ889050 - FJ889057.

RESULTS

Antagonistic activity

Forty three of the 63 Bacillus strains (68%) isolated from potato rhizosphere (6) were able to reduce the growth of R. solani with percentages of inhibition ranging from 69% to 91% (Table 1). Thirty nine of the 43 antagonistic strains (91%) were also able to control the growth of F. solani with percentages of inhibition ranging from 56% to 86% (Table 1). The non antagonistic strains grew normally and were not inhibited by the fungi (data not shown). There was not a significant correlation between the control capacity against the two pathogens (P > 0.05), yet some strains, like BacNe2c and Bac20M1, showed high inhibition against both fungi. Mainly saprophytic Bacillus species have been reported in potato rhizospheres but the potentially pathogenic B. cereus has also been obtained (5). All our antagonistic strains showed a negative reaction in the lecithinase test, suggesting that they did not belong to B. cereus.

Table 1.

Geographical origin and plant growth promoting activities of the antagonistic Bacillus strains isolated from potato rhizospheres.

| Growth inhibition (%) against | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | Geographical origin | R. solani | F. solani | PO4 solubilization halo (mm) | IAAa | BOX profileb |

| Bac3M3 | Huancavelica | 75.0 | 59.8 | 0 | + | |

| Bac3M4 | Huancavelica | 69.1 | 56.7 | 3 | + | |

| Bac3M5 | Huancavelica | 71.4 | 65.9 | 0 | + | A |

| Bac3M6 | Huancavelica | 59.5 | 0 | 7 | + | |

| Bac3M8 | Huancavelica | 83.3 | 57.9 | 0 | + | |

| Bac3M9 | Huancavelica | 82.1 | 60.1 | 0 | + | |

| Bac5M1 | Huancavelica | 70.2 | 65.9 | 0 | − | |

| Bac6M1 | Huancavelica | 79.8 | 69.9 | 2 | + | |

| Bac7M1 | Huancavelica | 84.5 | 75.6 | 0 | ++ | |

| Bac7M3 | Huancavelica | 77.4 | 74.7 | 0 | + | B |

| BacC7M1 | Huancavelica | 77.4 | 77.0 | 2 | +++ | |

| Bac8M7(1) | Huancavelica | 77.4 | 79.3 | 3 | − | C |

| Bac8M2 | Huancavelica | 83.3 | 0 | 1 | − | |

| Bac13M3 | Puno | 89.3 | 0 | 9 | + | |

| Bac14M1a | Puno | 75.0 | 65.5 | 0 | + | C |

| Bac14M1b | Puno | 84.5 | 74.7 | 0 | + | |

| Bac14M1c | Puno | 81.0 | 81.7 | 0 | + | |

| Bac15Ma | Puno | 86.9 | 78.6 | 0 | + | |

| Bac15Mb | Puno | 82.1 | 77.9 | 4 | + | C |

| Bac17M7 | Puno | 84.5 | 63.2 | 0 | + | |

| Bac17M8 | Puno | 84.5 | 70.1 | 5 | + | |

| Bac17M9 | Puno | 79.8 | 63.2 | 0 | ++++ | D |

| Bac17M10 | Puno | 81.0 | 63.2 | 3 | +++ | |

| Bac17M11 | Puno | 86.9 | 63.2 | 5 | + | E |

| Bac17M12 | Puno | 76.2 | 77.0 | 0 | − | |

| Bac17M13 | Puno | 85.7 | 72.4 | 0 | ++ | H |

| Bac17M8+ | Puno | 89.3 | 77.9 | 3 | ++ | |

| Bac17M21a | Puno | 77.4 | 54.9 | 2 | − | |

| Bac17M22b | Puno | 88.1 | 60.2 | 2 | +++ | |

| Bac19M1 | Puno | 85.7 | 0 | 3 | +++ | |

| Bac20M1 | Puno | 91.7 | 83.1 | 5 | ++ | E |

| Bac20M2 | Puno | 89.3 | 80.5 | 2 | − | E |

| BacYU1 | Puno | 76.2 | 79.8 | 0 | − | H |

| Bacbla1a | Huancavelica | 75.0 | 72.4 | 3 | + | H |

| Bacbla1b | Huancavelica | 86.9 | 72.4 | 4 | + | |

| Bacbla1c | Huancavelica | 79.8 | 77.0 | 2 | − | H |

| BacNeIB1 | Huancavelica | 86.9 | 63.2 | 0 | ++ | |

| BacNeIB1a | Huancavelica | 84.5 | 70.1 | 3 | + | |

| BacNeIB1b | Huancavelica | 79.8 | 65.5 | 0 | + | H |

| BacNe2a | Huancavelica | 78.6 | 72.4 | 3 | + | C |

| BacNe2b | Huancavelica | 82.1 | 72.4 | 4 | + | |

| BacNe2c | Huancavelica | 86.9 | 86.9 | 2 | + | |

| BacNe2d | Huancavelica | 81.0 | 77.8 | 2 | + | C |

| Bac3M2 | Huancavelica | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | H |

| Bac3M7 | Huancavelica | 0 | 0 | 0 | − | G |

| FZB24c | 72.6 | 60.8 | 0 | + | ||

Arbitrary colorimetric scale of IAA production from - (no production) to ++++ (high production).

Only a subset of strains were analyzed

Commercially used Bacillus amyloliquefaciens strain.

IAA production and phosphate solubilization

The majority of the antagonistic strains (81%) produced IAA to various extents (Table 1). Twenty five of the positive strains (71%) produced it to the same level as the commercially-used B. amyloliquefaciens FZB24 control strain, while the remaining showed higher production (Table 1). The phosphate solubilization process, observed as growing solubilization haloes in a 30 d period, was progressive and reaches its maximum between the 10 and 15 d of incubation for all the isolates (data not shown). Twenty five out of the 43 antagonistic strains (58%) were able to solubilize tricalcium phosphate with maximum halo sizes varying between 1 and 9 mm (Table 1). There was not significant correlations (P > 0.05) between any pair of plant growth promoting activities except for a slight negative correlation between phosphate solubilization and the antagonism against F. solani (r = -0.39, P = 0.0105). We did not find any relationship between the plant growth promoting abilities of the strains and their geographical origin.

Phylogenetic affiliation

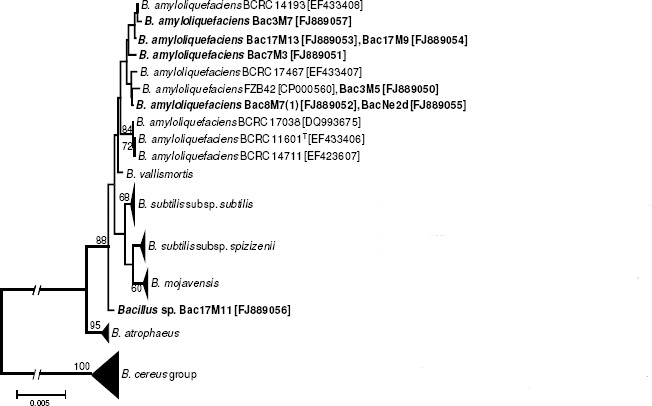

Eight strains showing antagonism against both fungi were randomly chosen from each geographical region to be subjected to phylogenetic analysis. Two non-antagonistic strains (Bac3M2 and Bac3M7) were also included. Genomic fingerprinting of these 18 strains revealed eight distinct BOX profiles (Table 1). Eight strains representing seven of the BOX profiles were selected for 16S rRNA gene sequencing. The phylogram presented in Fig. 1 showed that the potato strains belonged to the ‘B. subtilis group’ phylogenetic branch (34). The Bac17M11 strain occupied an independent position indicating that it belong to a not yet described Bacillus species, while the remaining strains were intermingled with B. amyloliquefaciens, indicating that they belong to this species. The non-antagonistic strains were closely related to the antagonistic strains by BOX fingerprinting (Table 1) or 16S rRNA gene sequence (Fig. 1) indicating that strains possessing similar genomic backgrounds or 16S phylogeny may widely vary in their antagonistic abilities.

Figure 1.

Neighbor joining phylogeny of 1390 aligned positions (without gaps) of the 16S rRNA gene of the antagonistic potato-associated Bacillus (shown in bold) and related Bacillus species. Strains having the same sequence are shown in the same terminal branch. Sequence accession numbers of the Bac17M11 strain and all the B. amyloliquefaciens strains are given within brackets. Only boostrap values greater than 60% are shown.

DISCUSSION

The results of this research evidenced a high prevalence of antagonistic Bacillus towards R. solani and F. solani in the rhizosphere of potatoes growing in their natural habitat in the Andes. In other studies where a collection of Bacillus strains has been challenged against R. solani, only 9.5 to 36% were antagonistic to this pathogen (9, 20). In vitro antagonism towards R. solani has been previously found in Bacillus spp. isolated from several sources (9, 10, 19, 20, 24), including potato rhizosphere (5). The reported growth inhibitions are generally lower than those obtained here, ranging from 28 to 74% (19–21, 24). In contrast to the ample literature involving R. solani, only in few studies Bacillus spp. has been challenged against F. solani (10, 19, 29). The behavior reported ranged from no inhibition (29) to 10–64% growth reduction (10, 19).

A relatively wide range of antagonistic performances among Bacillus strains was observed here and has also been noted in other studies involving the same or different fungi (16). Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the inhibition of fungal pathogens by Bacillus spp., including production of antimicrobials, secretion of hydrolytic enzymes, competition for nutrients, or a combination of mechanisms (7). Given that more than one mechanism may be involved, a complex response with a range of antagonistic effects among Bacillus strains and distinct responses by different pathogens could be expected as was observed here.

The capacity to produce phytohormones, like auxins, is a desirable characteristic of a PGPR (33). Several species of Bacillus have been reported to produce auxins. Idris et al. (15) have shown that mutants of B. amyloliquefaciens FZB42 with diminished levels of IAA production were less efficient in promoting plant growth. Although low IAA production scores were assigned to the majority of our strains, it has been shown that even low concentrations can induce an increase in the radical length and the number of secondary roots, and not always high concentrations results in a better growth promotion (27).

Several microorganisms are able to make insoluble soil phosphorous available to plants by solubilizing mineral phosphates through the production of organic acids or phosphatases. Pseudomonas and Azotobacter are two of the most reported phosphate solubilization genera; however Bacillus strains also have this capacity (8, 22, 33). The phosphate solubilization abilities of our strains were similar to those reported for other Bacillus tested under similar assay conditions (8, 22).

Some of the strains characterized by BOX fingerprinting and 16S rRNA gene phylogeny seemed to belong to a novel Bacillus species but the majority of the strains were ascribed to B. amyloliquefaciens, a species with several reported PGPR representatives like FZB24. Reva et al. (25) proposed the existence of two ecotypes within B. amyloliquefaciens, one including the type strain and other including strains that seems to be well adapted to plant colonization. Interestingly, the B. amyloliquefaciens strains isolated here formed a subcluster separated from the type strain (Fig. 1), that subcluster may correspond to the plant-associated ecotype proposed by Reva et al. (25). It is worth to note that strains belonging to B. amyloliquefaciens are considered safe for use in biotechnological applications.

The results obtained indicate that the rhizosphere of potato is a rich source of potential PGPR strains of Bacillus. Some of the strains isolated here are currently being tested for plant growth promoting effects on potato in greenhouse experiments.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A. López-López, M. A. Rogel-Hernández, Mónica Rosenblueth, and L. Raymundo are thanked for technical assistance. This research was supported by Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (Concytec), Integrated Crop Management Division of International Potato Center (CIP), FDA biol-111/UNALM, DGAPA-PAPIIT IN200709 project, and Red Biofag-Cyted. We are grateful to Dr. Andreas Oswald (CIP) for his support in the collection of samples.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anguiz R., Martin C. Anastomosis groups, pathogenicity, and other characteristics of Rhizoctonia solani isolated from potatoes in Peru. Plant Disease. 1989;73(3):199–201. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asaka O., Shoda M. Biocontrol of Rhizoctonia solani damping-off of tomato with Bacillus subtilis RB14. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1996;62(11):4081–4085. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.11.4081-4085.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnett H.L., Hunter B.B. Illustrated Genera of Imperfect Fungi. American Phytopathological Society: St. Paul; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bashan Y. Inoculants of plant growth-promoting bacteria for use in agriculture. Biotechnol. Adv. 1998;16(4):729–770. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berg G., Krechel A., Ditz M., Sikora R.A., Ulrich A., Hallmann J. Endophytic and ectophytic potato-associated bacterial communities differ in structure and antagonistic function against plant pathogenic fungi. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2005;51(2):215–229. doi: 10.1016/j.femsec.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calvo-Vélez P., Reymundo-Meneses L., Zúñiga-Dávila D. A study of potato (Solanum tuberosum) crop rhizosphere microbial population in highland zones. Ecol. Apl. 2008;7(1,2):141–148. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Compant S., Duffy B., Nowak J., Clement C., Barka E.A. Use of plant growth-promoting bacteria for biocontrol of plant diseases: principles, mechanisms of action, and future prospects. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71(9):4951–4959. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.9.4951-4959.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chatli A.S., Beri V., Sidhu B.S. Isolation and characterisation of phosphate solubilising microorganisms from the cold desert habitat of Salix alba Linn. in trans Himalayan region of Himachal Pradesh. Indian J. Microbiol. 2008;48(2):267–273. doi: 10.1007/s12088-008-0037-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho K.M., Hong S.Y., Lee S.M., Kim Y.H., Kahng G.G., Lim Y.P., Kim H., Yun H.D. Endophytic bacterial communities in ginseng and their antifungal activity against pathogens. Microb. Ecol. 2007;54(2):341–351. doi: 10.1007/s00248-007-9208-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daami-Remadi M., Ayed F., Jabnoun-Khiareddine H., Hibar K., El Mahjoub M. Effects of some Bacillus sp. isolates on Fusarium spp. in vitro and potato tuber dry rot development in vivo. Plant Pathol. J. 2006;5(3):283–290. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies Jr F.T., Calderón C.M., Huaman Z., Gómez R. Influence of a flavonoid (formononetin) on mycorrhizal activity and potato crop productivity in the highlands of Peru. Sci. Hortic. 2005;106(3):318–329. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glickmann E., Dessaux Y. A critical examination of the specificity of the Salkowski reagent for indolic compounds produced by phytopathogenic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995;61(2):793–796. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.2.793-796.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon S.A., Weber R.P. Colorimetric estimation of indoleacetic acid. Plant Physiol. 1951;26(1):192–195. doi: 10.1104/pp.26.1.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Health-Protection-Agency. Identification of Bacillus species. National Standard Method BSOP ID 9 Issue 2.1; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Idris E.E., Iglesias D.J., Talon M., Borriss R. Tryptophan-dependent production of indole-3-Acetic Acid (IAA) affects level of plant growth promotion by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2007;20(6):619–626. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-6-0619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Idris H.A., Labuschagne N., Korsten L. Screening rhizobacteria for biological control of Fusarium root and crown rot of sorghum in Ethiopia. Biol. Control. 2007;40(1):97–106. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Idriss E.E., Makarewicz O., Farouk A., Rosner K., Greiner R., Bochow H., Richter T., Borriss R. Extracellular phytase activity of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB45 contributes to its plant-growth-promoting effect. Microbiology. 2002;148(Pt 7):2097–2109. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-7-2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnsson L., Hökeberg M., Gerhardson B. Performance of the Pseudomonas chlororaphis biocontrol agent MA 342 against cereal seed-borne diseases in field experiments. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 1998;104(7):701–711. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knaak N., Rohr A.A., Fiuza L.M. In vitro effect of Bacillus thuringiensis strains and cry proteins in phytopathogenic fungi of paddy rice-field. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2007;38(3):526–530. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mojica-Marín V., Luna-Olvera H.A., Sandoval-Coronado C.F., Pereyra-Alférez B., Morales-Ramos L.H., Hernández-Luna C.E., Alvarado-Gomez O.G. Antagonistic activity of selected strains of Bacillus thuringiensis against Rhizoctonia solani of chili pepper. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2008;7(9):1271–1276. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montealegre J.R., Reyes R., Pérez L.M., Herrera R., Silva P., Besoain X. Selection of bioantagonistic bacteria to be used in biological control of Rhizoctonia solani in tomato. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2003;6(2):38–50. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nautiyal C.S. An efficient microbiological growth medium for screening phosphate solubilizing microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1999;170(1):265–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nelson P.E., Toussoun T.A., Marasas W.F.O. Fusarium species: An Illustrated Manual for Identification. New York: Pennsylvania State Uniervsity Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rajendran L., Samiyappan R. Endophytic Bacillus species confer increased resistance in cotton against damping off disease caused by Rhizoctonia solani. Plant Pathol. J. 2008;7(1):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reva O.N., Dixelius C., Meijer J., Priest F.G. Taxonomic characterization and plant colonizing abilities of some bacteria related to Bacillus amyloliquefaciens and Bacillus subtilis. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2004;48(2):249–259. doi: 10.1016/j.femsec.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schisler D.A., Slininger P.J., Behle R.W., Jackson M.A. Formulation of Bacillus spp. for biological control of plant diseases. Phytopathology. 2004;94(11):1267–1271. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2004.94.11.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Selvadurai E.L., Brown A.E., Hamilton J.T.G. Production of indole-3-acetic acid analogues by strains of Bacillus cereus in relation to their influence on seedling development. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1991;23(4):401–403. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sessitsch A., Kan F.Y., Pfeifer U. Diversity and community structure of culturable Bacillus spp. populations in the rhizospheres of transgenic potatoes expressing the lytic peptide cecropin B. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2003;22(2):149–158. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siddiqui I.A., Ehetshamul-Haque S., Shahid Shaukat S. Use of rhizobacteria in the control of root rot-root knot disease complex of mungbean. J. Phytopathol. 2001;149(6):337–346. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tamura K., Dudley J., Nei M., Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2007;24(8):1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Torres H. Manual de las enfermedades más importantes de la papa en el Perú. Lima: International Potato Center (CIP); 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Versalovic J., Schneider M., De Bruijn F.J., Lupski J.R. Genomic fingerprinting of bacteria using repetitive sequence-based polymerase chain reaction. Meth. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994;5(1):25–40. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vessey J.K. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria as biofertilizers. Plant Soil. 2003;255(2):571–586. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang L.T., Lee F.L., Tai C.J., Kasai H. Comparison of gyrB gene sequences, 16S rRNA gene sequences and DNA-DNA hybridization in the Bacillus subtilis group. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007;57(8):1846–1850. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64685-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weisburg W.G., Barns S.M., Pelletier D.A., Lane D.J. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J. Bacteriol. 1991;173(2):697–703. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.697-703.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zar J.H. Biostatistical Analysis. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall; 1984. [Google Scholar]