Abstract

Successful integration of advanced semiconductor devices with biological systems will accelerate basic scientific discoveries and their translation into clinical technologies. In neuroscience generally, and in optogenetics in particular, an ability to insert light sources, detectors, sensors and other components into precise locations of the deep brain could yield versatile and important capabilities. Here, we introduce an injectable class of cellular-scale optoelectronics that offers such features, with examples of unmatched operational modes in optogenetics, including completely wireless and programmed complex behavioral control over freely moving animals. The ability of these ultrathin, mechanically compliant, biocompatible devices to afford minimally invasive operation in the soft tissues of the mammalian brain foreshadow applications in other organ systems, with potential for broad utility in biomedical science and engineering.

Electronic systems that integrate with the body provide powerful diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities for basic research and clinical medicine. Recent research establishes materials and mechanical constructs for electronic circuits, light emitting diodes (LEDs), sensors and other components that can wrap the soft, external surfaces of the brain, skin and heart, for diverse function in analytical measurement, stimulation and intervention (1–10). A significant constraint in operating these devices, however, follows from their surface-mounted configurations and inability to provide direct interaction into the volumetric depths of the tissues. Passive penetrating electrodes or optical fibers with interconnections to externally located electronic control/acquisition systems or light sources can be valuable in many contexts, particularly in neuroscience, engineering and surgery (7, 10–14). Direct biological integration is limited by challenges from tissue lesions during insertion, persistent irritation, and engineering difficulties in thermal management, encapsulation, scalable interconnection, power delivery and external control. Many of these issues constrain attempts to insert conventional, bulk LEDs into brain tissue (15), and to use semiconductor nanowire devices as cellular probes or active, in vitro tissue scaffolds (3, 16). In optogenetics, engineering limitations of conventional, tethered fiber optic devices restrict opportunities for in vivo use and widespread biological application. As a solution, we developed mechanically compliant, ultrathin multifunctional optoelectronic systems that mount on releasable injection needles for insertion into the depth of soft tissue. These wireless devices incorporate cellular-scale components ranging from independently-addressable multi-colored microscale, inorganic light emitting diodes (μ-ILEDs) to co-located, precision optical, thermal and electrophysiological sensors and actuators.

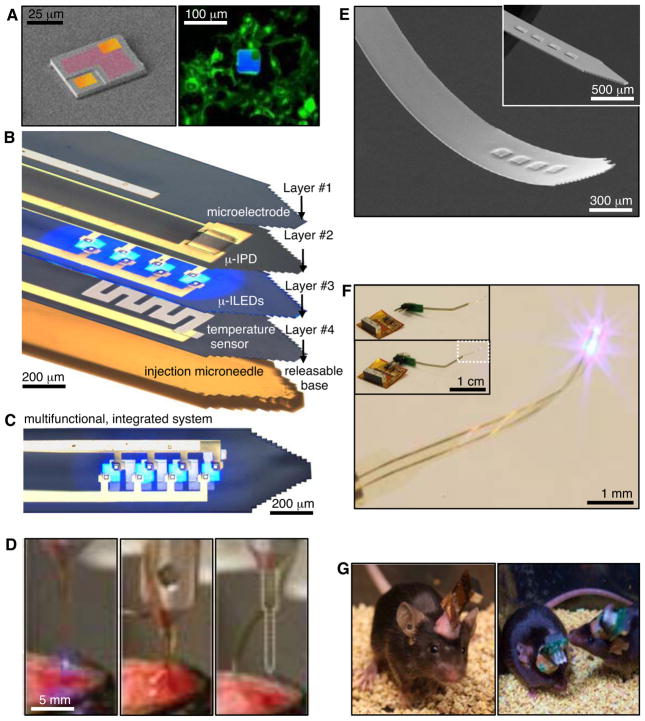

Figure 1A presents a scanning electron micrograph (SEM) of an isolated GaN μ-ILED, as a constituent component of these systems, and an epifluorescent image of a device among cultured HEK293 cells to illustrate the similar sizes. Each such ‘cellular-scale’ μ-ILED (6.45 μm thick, 50×50 μm2) uses high-quality epitaxial material grown on sapphire, processed to establish contacts (15×15 μm2 square pads in the corners, and an L-shaped current spreading layer for the p-contact) and then released, to allow transfer printing onto narrow, thin plastic strips. The μ-ILEDs are more than a thousand times smaller than conventional LEDs (typically 100 μm thick, with lateral dimensions of 1 mm2) and fiber optic probes, as discussed subsequently (17). The small sizes of μ-ILEDs allow for spatially precise, cellular-scale delivery of photons, highly effective thermal management, reduced tissue damage, and minimized inflammation for prolonged use in vivo.

Fig. 1.

Injectable, cellular-scale semiconductor devices, with multifunctional operation in stimulation, sensing and actuation. (A) Left, colorized SEM (left) of a GaN μ-ILED (~6.45 μm thick, and 50×50 μm2; contacts – gold; spreading layer – red). Right, fluorescent image of a μ-ILED (blue) with cultured HEK293 cells that express an eYFP tagged transmembrane protein (green). (B) A multifunctional, implantable optoelectronic device, in a tilted exploded view layout illustrating various components. The system includes layers for electrophysiological measurement (#1; Pt contact pad, microelectrode), optical measurement (#2; silicon μ-IPD), optical stimulation (#3; μ-ILED array), and temperature sensing (#4; serpentine Pt resistor), all bonded to a releasable structural support for injection (microneedle). (C) Top view of the integrated device shown in (B). (D) Process of injection and release of the microneedle. After insertion, aCSF (center) dissolves the external silk-based adhesive. The microneedle is removed (right) leaving only the active device components in the brain. (E) SEM of an injectable array of μ-ILEDs. The total thickness is 8.5 μm. Inset shows rigid device before coating with a passivation layer. (F) Integrated system wirelessly powered with RF scavenging. Insets show a connectorized device unplugged (top) and plugged into (bottom) the wireless power system. (G) Healthy, freely-moving mice with lightweight, flexible (left) and rigid (right) wireless systems powering GaN μ-LED arrays in the VTA.

Combining μ-ILEDs with electronic sensors and actuators yields multifunctional integrated systems that can be configured in single or multilayer formats. Figure 1B and C illustrate the latter option, in which the sensors/actuators include a Pt microelectrode for electrophysiological recording or electrical stimulation (Layer #1; a 20×20 μm2 exposure defines the active area), a microscale inorganic photodetector (μ-IPD) based on an ultrathin silicon photodiode (Layer #2; 1.25 μm thick, 200×200 μm2), a collection of four μ-ILEDs connected in parallel (Layer #3) and a precision temperature microsensor or microheater (Layer #4; Pt serpentine resistor) (more details in figs. S1–S3)(18). Each layer is processed on separate substrates shaped to match a releasable, photolithographically-defined epoxy microneedle (fig. S4). A thin layer (~500 nm) of epoxy joins each of the layers in a precisely aligned, stacked configuration. The microneedle bonds to the bottom layer with a thin, bio-resorbable adhesive based on a film of purified silk fibroin, enabling removal of the microneedle after implantation (Fig. 1D, Movie S1 and fig. S5). The microelectrodes measure extracellular voltage signals in the direct vicinity of illumination, and can also be used for stimulation (Fig. 2H). The temperature sensors determine the degree of local heating, with a precision approaching ~1 mK, and can also be used as microheaters. The μ-IPD can measure the intensity of light from the μ-ILEDs while implanted deep in brain tissue and/or enable basic spectroscopic evaluations of absorption, fluorescence, diffuse scattering, etc. For detailed information see figs. S6 and S7 (18).

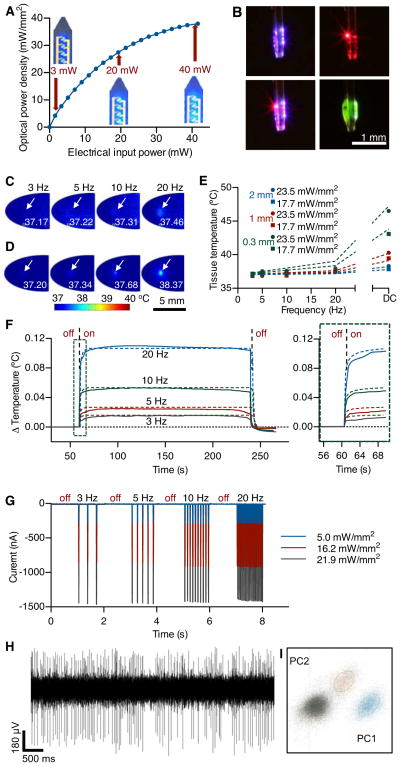

Fig. 2.

Optical, thermal, and electrophysiological studies with corresponding theoretical analyses. (A) Total optical power density as a function of electrical input power applied to an array of four GaN μ-ILEDs; optical images show operation at 3, 20 and 40 mW. (B) A single device has one 675 nm GaAs μ-ILED and four 450 nm GaN μ-ILEDs that can be activated independently (upper left and upper right) or concurrently (lower left). The same device is coated in a fluorescein sodium salt phosphor for 530 nm light (lower right). (C) Measured and (D) calculated temperatures in explanted brain tissue near implanted μ-ILEDs at a depth of 0.3 mm and operated at 17.7 mW/mm2 of light output power. (E) Temperatures in a system similar to that of (C, D), as a function of duty cycle in the operation of the μ-ILEDs and at three different implantation depths (0.3, 1.0, 2.0 mm) and two different light output powers (17.7, 23.5 mW/mm2). (F) Change in brain temperature as a function of time, measured using an integrated temperature sensor co-located with an array of four μ-ILEDs in a lightly anesthetized mouse. Results evaluated at a peak input electrical power of 8.65 mW, in 3, 5, 10, and 20 Hz pulses (10 ms duration). The vertical dashed lines indicate onset (at 60 s) and offset (at 240 s) of the μ-ILEDs. Colored dashes lines correspond to theoretical models for the temperature. The right frame shows the time dynamics as the device is powered. (G) Change in photocurrent as a function of time, measured using an integrated μ-IPD, for three different light output powers to an array of μ-ILEDs: 5.0 mW/mm2 (blue trace), 16.2 mW/mm2 (red trace), and 21.9 mW/mm2 (black trace) at different pulse frequencies (10 ms pulses at 3, 5, 10, and 20 Hz). (H) 5 s extracellular voltage trace of spontaneous neuronal activity gathered using the integrated Pt microelectrode. (I) The same data is filtered and sorted using principal components analysis to identify single units.

Injection of such flexible devices into the brain follows steps shown in Fig. 1D and Movie S1. The injected multifunctional optoelectronic systems, have a total thickness of ~20 μm. This exceptionally thin geometry, low bending rigidity, and high degree of mechanical flexibility (Figs. 1E and F) allows for minimally invasive operation. Wired control schemes use standard transistor-transistor logic (TTL) and are therefore compatible with any readily available electrical commutator. Details on wired powering strategies and demonstration of wired optogenetic functionality in rodent behavioral assays are presented in figs. S8, S9, and S10. (18). Figure 1F shows implementation of a wireless power module based on radiofrequency (RF) scavenging. A custom flexible polyimide film-based lightweight (~0.7 g) power scavenger or a rigid printed circuit board-based scavenger (~2.0 g; Fig. 1G and fig. S11) can be acutely and temporarily mounted on freely moving animals without constraint in natural animal behavior (Fig. 1G). The entire system consists of a wireless power transmitter and RF signal generator, an RF source (910 MHz; power output between 0.02 and 0.1 mW), a power supply, an RF power amplifier (gain of 49 dB at 910 MHz; power output between 1.6 and 7.9 W), and a panel antenna (gain of 13 dBi), as in fig. S11 and fig. S12. The low-frequency signal generator provides user-controlled amplitude modulation for programmed operation. The RF power that reaches the animals, under normal operating conditions at a distance of ~1 m, is between 0.15 and 0.77 mW/cm2, which is substantially smaller than the maximum permissible exposure (MPE) limits (3.03 mW/cm2) for humans in controlled environments (19). Wireless control allows access to complex and ethologically relevant models in diverse environmental settings, including social-interactions, homecage behaviors, wheel running, complex maze navigation tasks, and many other behavioral outputs (Fig. 1G and fig. S13).

The electrical, optical and thermal characteristics of the devices when operated in biological environments are important for optogenetics and other biomedical applications. Figure 2A shows the total optical power density of the four μ-ILEDs in this device as a function of electrical input power (more details in fig. S14 and S15)(18). This performance is comparable to similarly designed, state-of-the-art conventional GaN LEDs (17). Many optogenetic constructs can be activated with ~1 mW/mm2, at wavelengths near 450 nm (13). These conditions are well matched to the output of the GaN μ-ILEDs. Input power of ~1.0–1.5 mW (Fig. 2A) is sufficient for both activation of the channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2(H134)) ion channel and precise control of intracellular signaling (cAMP and ERK 1/2) via an optically sensitive G-protein coupled receptor (OPTO-β2) (20) (Fig. 3C and D, figs. S16 and S17). Wirelessly, at a distance of one meter, the RF scavenger outputs 4.08 mW of electrical power resulting in a 7 mW/mm2 optical power density. Other wavelengths are possible using different types of μ-ILEDs, either in multicolored or uniform arrays. Fig. 2B shows an example of the latter, with blue and red (GaAs) μ-ILEDs, and the former, with green devices (produced using fluorescein sodium salt phosphor on a blue GaN μ-ILED).

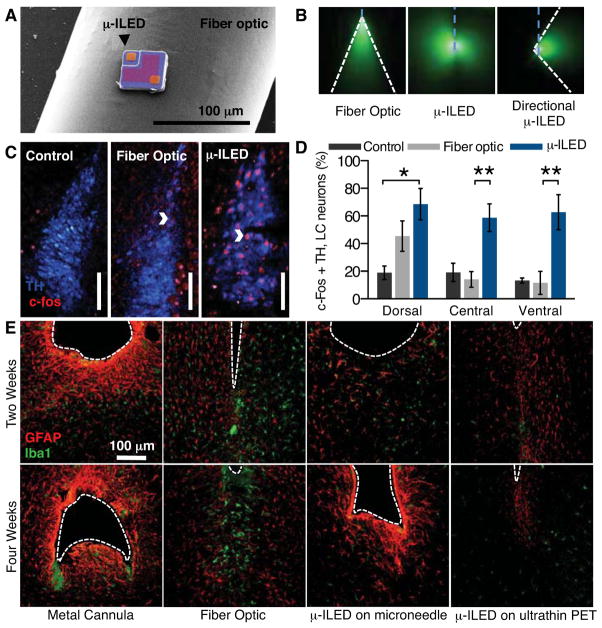

Fig. 3.

μ-ILED devices improve spatial targeting and reduce gliosis. (A) Colorized SEM (left) of a μ-ILED mounted on a standard 200 μm fiber optic implant. (B) Left, a dorsal-ventral oriented light cone (outlined in white) from a 200 μm bare fiber implant (blue dash) emitting 465 nm light in 30 μM fluorescein water. Center, near omnidirectional light escape from a μ-ILED device (blue dash) with four 450 nm μ-ILEDs. Right, lateral light escape (outlined in white) from a modified μ-ILED device (blue dash) to allow unique spatial targeting including flanking positions along the dorsal-ventral axis of brain loci. (C) Confocal fluorescence images of 30 μm brainstem slices containing the LC show staining for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and c-fos in control (left), fiber optic implanted (center), and μ-ILED device implanted (right) animals following 1 hour 3 Hz photostimulation (15 ms pulses, 5 mW output power). Scale bar = 100 μm. (D) Fiber optic and μ-ILED treatments specifically increase co-immunoreactivity. Ventral portions of the LC the μ-ILED devices express a higher proportion of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH, blue) and c-fos (red) co-immunoreactive neurons than fiber optic or control groups (n = 3 slices per brain from 3 brains for each group; Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc; All error bars represent means ± SEM; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01). (E) Confocal fluorescence images of 30 μm striatal slices show staining for astrocytes (GFAP, red) and activated microglia (Iba1, green) at the ventral tip of each implanted device (dashed outline). Gliosis is smallest with the μ-ILED device at both two- and four-week time points.

Fig. 2C and D show μ-ILED-induced changes in temperature determined by infrared imaging and by analytical calculation, respectively. The μ-ILEDs were implanted 0.3 mm into an explanted piece of brain tissue held at 37 °C. The time-averaged temperatures measured at light-pulse (10 ms) frequencies of 3, 5, 10, and 20 Hz with peak light output of 17.7 mW/mm2 are 37.17, 37.22, 37.31, and 37.46 °C, respectively. These results are similar to calculated time-averaged temperatures of 37.20, 37.34, 37.68, and 38.37 °C, respectively. Importantly, the input power used in these tests is ten times greater than what is necessary to activate many optogenetic constructs (13). The cellular-scale dimensions of the μ-ILEDs enable high rates of passive thermal spreading and the brain tissue itself operates as an efficient heat sink. The latter is apparent in studies of the dependence of operating temperature on tissue thickness, operating power and frequency (Fig. 2E). As in Fig. 2D, the experiment and theory agree remarkably well in spite of the indirect correlation between infrared imaging results and temperature at the location of the devices (Details appear in figs. S18 and S19)(18). Perfusion in living tissue further increases the efficacy of these biological heat sinks. Figure 2F shows changes in temperature measured in vivo using an integrated temperature sensor (fig. S6) compared to calculated results. Collectively, these results indicate that changes in temperature associated with operation of μ-ILEDs can be less than 0.10 °C for pulse frequencies less than 20 Hz, typical of many neuronal firing rates. These values are much lower than those that occur in human deep brain stimulation (DBS) regulation, ~2°C (21). Furthermore, in wireless operation, there is no appreciable change in temperature associated with operation at the headstage antenna or the skull (fig. S20).

Other components of this multifunctional platform exhibit similarly good characteristics. To demonstrate functionality of the silicon μ-IPD, Fig. 2G shows photocurrents generated by different intensities of light from μ-ILEDs at different pulse frequencies. Finally, the Pt microelectrode has a 400 μm2 exposure site with ~1.0 MΩ impedance at 1 kHz capable of measuring extracellular potentials on the μV scale necessary to distinguish individual action potentials (Fig. 2H) as demonstrated with clear clustering in the principal component analysis of spike data (Fig. 2I).

For use in optogenetics, such devices eliminate the need for lasers, bulk LEDs, fiber coupling systems, tethers, and optomechanical hardware used in conventional approaches (fig. S8). Furthermore, the fundamental optics of μ-ILEDs are much different than typical fiber optic implants. Absorbing/reflecting structures around the emissive areas of the μ-ILEDs enable precise delivery of light to cellular sub-regions. Figs. 3A and B compare relative size and the different patterns of light emission from μ-ILEDs to fiber optic probes. Fiber optics typically approach brain structures dorsally. This approach preferentially illuminates cells in the dorsal portion of the targeted region with greater light intensity near the point of light escape (22) (Fig. 3B left, & fig. S21). Targeting ventral cell bodies or terminals requires lesion of dorsal regions or the use of substantially greater, and potentially phototoxic (23), amounts of light to the site of interest. Neither option protects the intact architecture of a complete brain locus. Though recent advances have spatially restricted light from implanted fiber optics (24, 25), these approaches require the use of invasive metal cannulae (Fig. 3E) or rely on sophisticated and sensitive optomechanical engineering that may limit use in awake, behaving animals. The architecture of the μ-ILEDs enables light delivery medial or lateral to the intended target brain region. Native light escape from μ-ILEDs is nearly omni-directional (Fig. 3B, center), but can be restricted to a wide range of angles with absorbing or reflective structures on the device (Fig. 3B, right).

We acutely implanted both μ-ILEDs and fiber optics into animals expressing ChR2(H134)-eYFP in the LC (fig. S21). One hour of output-matched photostimulation induced c-fos expression (26), a biochemical marker of neuronal activation, in both groups of ChR2(H134)-eYFP expressing mice that was not seen in GFP expressing controls (Fig. 3C and Fig. 3D). The spatial distribution of c-fos expression, however, differed markedly between the fiber optic and μ-ILED groups. μ-ILED devices produced significantly greater activation in the ventral LC (Fig. 3D).

The physical sizes and mechanical properties of the μ-ILED systems reduce lesioning, neuronal loss, gliosis, and immunoreactivity. Glial responses are biphasic with an early phase featuring widespread activation of astrocytes and microglia and a late, prolonged phase hallmarked by restriction of the gliosis to the area closest to the implanted substrate (27). The μ-ILED devices produced substantially less glial activation and caused smaller lesions as compared to metal cannulae and fiber optics, at both early (two weeks) and late (four weeks) phases (Fig. 3E). Furthermore, the brain tolerates the thin, flexible devices better than rigid structures (Fig. 3E), consistent with reports on passive electrode devices (28). Finally, we examined the chronic functionality of the devices and demonstrated that they are well tolerated in freely moving animals with encapsulated sensors and μ-ILEDs maintaining function over several months (S22).

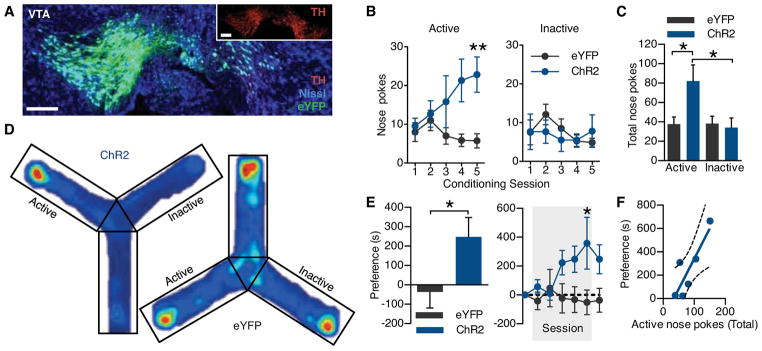

We next implemented a fully wireless system for dissecting complex neurobiology and behavior. Phasic neuronal firing of VTA-dopaminergic (VTA-DA) neurons encodes salient stimuli and is sufficient for behavioral conditioning (29–32). We selectively targeted ChR2(H134)-eYFP to VTA-DA neurons (Fig. 4A) and tested whether mice would engage in wireless, optical self-stimulation (20, 5 ms pulses every nose poke) of their dopamine reward pathway. To increase the contextual salience of the stimulation and demonstrate wireless function of the μ-ILED devices, the mice were free to explore a complex environment (fig. S23, A–C). In the absence of physical reward, the same stimulation of VTA-DA neurons that drives a traditional conditioned place preference (fig. S9) (29, 30) is actively sought with a cued nose poke when paired within a discrete environmental context. ChR2(H134)-eYFP mice learned to self-stimulate their dopamine neurons (Fig. 4B and C) and, furthermore, developed a robust place preference (Fig. 4D and E) for the environmental context containing the active nose poke for VTA-DA stimulation. ChR2(H134)-eYFP animals showed strong correlation (r = 0.8620, p = 0.0272) between the number of active nose pokes and the magnitude of conditioned place preference that was absent in eYFP controls (Fig. 4F and fig. S23E). In addition, we examined the effects of wireless tonic stimulation of VTA-DA neurons on anxiety-like behavior. 5 Hz tonic stimulation reduced anxiety-like behavior whereas phasic activation of VTA-DA neurons did not have an effect on anxiety-like behavior (fig. S24). These findings are consistent with the anxiolytic actions of nicotine on VTA-DA neurons as well as the behavioral phenotypes seen in the ClockΔ19 mice that have increased tonic firing of VTA-DA neurons (33, 34) and further establish the utility of wireless optogenetic control in multiple environmental contexts.

Fig. 4.

Wirelessly powered μ-ILED devices operantly drive conditioned place preference. (A) Cell-type specific expression of ChR2(H134)-eYFP (green) in dopaminergic, TH (red) containing neurons of the VTA. For clarity, inset shows TH channel alone. All scale bars = 100 μm. (B) Operant learning curve on the active (left) and inactive (right) nose poke devices over 5 days of 1-hour trials in the Y-maze. Active pokes drive 1 s of 20 Hz light (5 ms pulses) from the μ-ILED device on a fixed-ratio-1 schedule (n = 6–8 mice/group; Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc; **p < 0.01). (C) Mean number of nose pokes ± SEM across all five conditioning sessions. (*p < 0.05 One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc) (D) Heat maps of activity during the post-test, hotter colors represent longer duration in a location in that part of the apparatus. (E) Left, place preference scores calculated as post-test minus pre-test in the active nose poke-paired context. Five days of self-stimulation significantly conditioned a place preference that developed over the course of the training sessions and remained during the post-test (right; *p < 0.05 t-test compared to controls; *p < 0.05 Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc). All error bars represent means ± SEM (F) Scatter plot demonstrating positive correlation (r = 0.8620, p = 0.0272) between post-test preference and total number of active nose pokes during training in the ChR2(H134)-eYFP group.

These experiments demonstrate that these devices can be readily used in optogenetic experiments. Future possible uses are in closed-loop operation, where actuators (heat, light, electrical, etc) operate in tandem with sensors (temperature, light, potential, etc) for altering light stimulation in response to physiological parameters such as single unit activity, pH, blood oxygen or glucose levels, or neurochemical changes associated with neurotransmitter release. Many of the device attributes that make them useful in optogenetics suggest strong potential for broader use in biology and medicine. The demonstrated compatibility of silicon technology in these injectable, cellular-scale platforms foreshadows sophisticated capabilities in electronic processing and biological interfaces. Biocompatible deep tissue injection of semiconductor devices and integrated systems such as those reported here will accelerate progress in both basic science and translational technologies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by NIH Common Fund, NINDS R01NS081707 (M.R.B., J.A.R.), NIDA R00DA025182 (M.R.B.), McDonnell Center for Systems Neuroscience (M.R.B.), National Security Science and Engineering Faculty Fellowship of Energy (J.A.R.), US Department of Energy, Division of Materials Sciences under Award No. DE-FG02-07ER46471 (J.A.R.), and the Materials Research Laboratory and Center for Microanalysis of Materials (DE-FG02-07ER46453) (J.A.R.). and WUSTL DBBS (J.G.M.). We thank Hu Tao (Tufts University) and Sukwon Hwang (UIUC) for their help in preparation of silk solution and valuable discussions. We thank the Bruchas laboratory and the laboratories of. Robert W. Gereau, IV (WUSTL) and Garret D. Stuber (UNC) for helpful discussion. We thank Karl Deisseroth (Stanford University) for the channelrhodopsin-2 (H134) and OPTO-β2 constructs, Stuber for the TH-IRES-Cre mice, the WUSTL Bakewell Neuroimaging Laboratory Core, and the WUSTL Hope Center Viral Vector Core.

References and Notes

- 1.Kim DH, et al. Dissolvable films of silk fibroin for ultrathin, conformal bio-integrated electronics. Nat Mater. 2010;9:511. doi: 10.1038/nmat2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Viventi J, et al. A conformal, bio-Interfaced class of silicon electronics for mapping cardiac electrophysiology. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:22. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tian B, et al. Three-diemensional, flexible, nanoscale field effect transistors as localized bioprobes. Science. 2010;329:830. doi: 10.1126/science.1192033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim DH, et al. Epidermal electronics. Science. 2011;333:838. doi: 10.1126/science.1206157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qing Q, et al. Nanowire transistor arrays for mapping neural circuit in acute brain slides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:1882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914737107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sekitani T, Someya T. Stretchable organic integrated circuits for large-area electronic skin surface. MRS Bull. 2012;37:236. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ordonez J, Schuettler M, Boehler C, Boretius T, Stieglitz T. Thin films and microelectrode arrays for neuroprosthetics. MRS Bull. 2012;37:590. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mannsfeld SCB, et al. Highly sensitive flexible pressure sensors with micro-structured rubber as the dielectric layer. Nat Mater. 2010;9:859. doi: 10.1038/nmat2834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sekitani T, et al. Organic nonvolatile memory transistors for flexible sensor arrays. Science. 2009;326:1516. doi: 10.1126/science.1179963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takeuchi S, Suzuki T, Mabuchi K, Fujita H. 3D flexible multichannel neural probe array. J Micromech Microeng. 2004;14:104–107. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stark E, Koos T, Buzsáki G. Diode probes for spatiotemporal optical control of multiple neurons in freely moving animals. J Neurophysiol. 2012;108:349–363. doi: 10.1152/jn.00153.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim Y-T, Romero-Ortega MI. Material considerations for peripheral nerve interfacing. MRS Bull. 2012;37:573. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mattis J, et al. Principles for applying optogenetic tools derived from direct comparative analysis of microbial opsins. Nat Methods. 2011;18:159. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anikeeva P, et al. Optetrode: a multichannel readout for optogenetic control in freely moving mice. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:163. doi: 10.1038/nn.2992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cao H, Gu L, Mohanty SK, Chiao J-C. An integrated μLED optrode for optogenetic stimulation and electrical recording. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2012.2217395. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tian B, et al. Macroprous nanowire nanoelectronic scaffolds for synthetic tissues. Nat Mater. 2012;11:986–994. doi: 10.1038/nmat3404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim TI, et al. High efficiency, microscale GaN LEDs and their thermal properties on unusually substrates. Small. 2012;8:1643–1649. doi: 10.1002/smll.201200382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Materials and methods are available as supporting material on Science Online.

- 19.Federal Communications Comission (FCC) . Guidelines for Evaluating the Environmental Effects of Radiofrequency Radiation. FCC Publication Docket No 93-62. 1996 http://transition.fcc.gov/Bureaus/Engineering_Technology/Orders/1996/fcc96326.txt.

- 20.Airan RD, Thompson KR, Fenno LE, Bernstein H, Deisseroth K. Temporally precise in vivo control of intracellular signalling. Nature. 2009;458:1025–1029. doi: 10.1038/nature07926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elwassif MM, Kong Q, Vazquez M, Bikson M. Bio-heat transfer model of deep brain stimulation-induced temperature changes. J Neural Eng. 2006;3:306. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/3/4/008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aravanis AM, et al. An optical neural interface: in vivo control of rodent motor cortex with integrated fiberoptic and optogenetic technology. J Neural Eng. 2007;4:S143–S156. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/4/3/S02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yizhar O, Fenno LE, Davidson TJ, Mogri M, Deisseroth K. Optogenetics in neural systems. Neuron. 2011;71:9–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tye KM, et al. Amygdala circuitry mediating reversible and bidirectional control of anxiety. Nature. 2011;471:358–362. doi: 10.1038/nature09820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zorzos AN, Scholvin J, Boyden ES, Fonstad CG. Three-dimensional multiwaveguide probe for light delivery to distributed brain circuits. Opt Lett. 2012;37:4841–3. doi: 10.1364/OL.37.004841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carter ME, et al. Tuning arousal with optogenetic modulation of locus coeruleus neurons. Nat Neuro. 2011;13:1526–1533. doi: 10.1038/nn.2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Szarowski DH, et al. Brain responses to micro-machined silicon devices. Brain Res. 2003;983:23–35. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshida Kozai1 TD, Kipke DR. Insertion shuttle with carboxyl terminated self-assembled monolayer coatings for implanting flexible polymer neural probes in the brain. J Neuro Met. 2009;184:199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsai H, et al. Phasic firing in dopaminergic neurons is sufficient for behavioral conditioning. Science. 2009;324:1080–1084. doi: 10.1126/science.1168878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adamantidis AR, et al. Optogenetic interrogation of dopaminergic modulation of the multiple phases of reward-seeking behavior. J Neurosci. 2011;31:10829–10835. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2246-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Witten IB, et al. Recombinase-driver rat lines: tools, techniques, and optogenetic application to dopamine-mediated reinforcement. Neuron. 2011;72:721–733. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim KM, et al. Optogenetic mimicry of the transient activation of dopamine neurons by natural reward is sufficient for operant reinforcement. Plos ONE. 2012;7:e33612. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGranahan TM, Patzlaff NE, Grady SR, Heinemann SF, Booker TK. $4%2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on dopaminergic neurons mediate nicotine reward and anxiety relief. J Neurosci. 2011;31:10891–902. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0937-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coque L, et al. Specific role of VTA dopamine neuronal firing rates and morphology in the reversal of anxiety-related, but not depression-related behavior in the ClockΔ19 mouse model of mania. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:1478–1488. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.