Abstract

The medullary raphé (MR) of the medulla oblongata contains chemosensitive neurons that respond to increases in arterial [CO2], by altering firing rate, with increases being associated with serotonergic (5-hydroxytryptamine [5HT]) neurons and decreases, with GABAergic neurons. Both types of neurons contribute to increased alveolar ventilation. Decreases in intracellular pH are thought to link the rise in [CO2] to increased ventilation. Because electroneutral Na+-coupled transporters (nNCBTs), which help protect cells from intracellular acidosis, are expressed robustly in the neurons of the central nervous system, a key question is whether these transporters are present in chemosensitive neurons. Therefore, we used an immunocytochemistry approach to identify neurons (using a microtubule associated protein-2 monoclonal antibody) and specifically 5HT neurons (TPH monoclonal antibody) or GABAergic neurons (GAD2 monoclonal antibody) in freshly dissociated cells from the mouse MR. We also co-labeled with polyclonal antibodies against the three nNCBTs: NBCn1, NDCBE, and NBCn2. We exploited ePet-EYFP (enhanced yellow fluorescent protein) mice (with EYFP-labeled 5HT neurons) as well as mice genetically deficient in each of the three nNCBTs. Quantitative image analysis distinguished positively stained cells from background signals. We found that >80% of GAD2+ cells also were positive for NDCBE, and >90% of the TPH+ and GAD2+ cells were positive for the other nNCBTs. Assuming that the transporters are independently distributed among neurons, we can conclude that virtually all chemosensitive MR neurons contain at least one nNCBT.

Keywords: intracellular pH regulation, SLC4 family, chemosensitive neurons, central nervous system

INTRODUCTION

The medulla oblongata is involved in a range of autonomic functions, including the regulation of the digestive, cardiovascular, and respiratory systems. Central chemoreceptors of the medulla oblongata, and elsewhere in the brainstem, sense increases in arterial [CO2] and initiate a reflex increase in both the depth and frequency of ventilation. The resulting increase in alveolar ventilation promotes CO2 elimination from the lungs, and thereby lowers arterial [CO2] toward normal values. The medullary raphé (MR)—located near the midline of the medulla, extending from the ventral surface—contains chemosensitive neurons that assist in the regulation of ventilation. One class of chemosensitive MR neurons are serotonergic (releasing 5-hydroxytryptamine [5HT]), and these respond to increases in arterial [CO2] with a sustained increase in firing rate, contributing to an increase in pulmonary ventilation (Wang et al., 2002; Richerson, 2004). Another class of chemosensitive MR neurons, which may represent a subpopulation of GABAergic neurons, respond to increases in [CO2] with a decrease in firing rate (Wang et al., 1998), presumably also contributing to an increase in ventilation. Both classes of chemosensitive neurons project to respiratory-related areas throughout the brainstem as well as the spinal cord, including the phrenic motor nucleus (PMN) (Connelly et al., 1989; Holmes et al., 1994; Hornung, 2003; Richerson, 2004; Cao et al., 2006).

Respiratory acidosis—a fall in pH caused by an increase in [CO2]—can be caused by a decrease in ventilation. An elevation in arterial [CO2] not only leads to a decrease in arterial pH but also—because CO2 readily crosses the blood–brain barrier—a fall in extracellular pH (pH0) and intracellular pH (pHi) of CNS (central nervous system) neurons and glia. The decrease in pH0 is proposed to be an adequate stimulus for the increase in firing rate of 5HT neurons in the MR (Corcoran et al., 2009). Several acid–base transporters in the plasma membrane of neurons and glial cells contribute to pHi regulation; and in response to acute intracellular acid loads, could restore pHi toward normal and thereby reduce a potential stimulus for increased ventilation. Acid-extruding transporters mediate either the efflux of acid (e.g., H+) from the cell or the uptake of alkali (e.g., ) into the cell. Examples in the CNS are the plasma membrane Na–H exchangers (NHE1-5) (Attaphitaya et al., 1999; Xue et al., 2003); and the electroneutral Na+-coupled transporters (nNCBTs)—the largest subfamily of the solute-linked carrier 4 (SLC4) family of transporters. The nNCBTs, which are heavily expressed in neuronal populations of the CNS (Romero et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2007, 2008a,b), respond to intracellular acid loads (e.g., caused by an increase in CO2) by transporting a -related species (e.g., CO=3) into the cell and thereby raising pHi. The Na+/ cotransporters NBCn1 and NBCn2 mediate what appears to be the uptake of 1 Na+ and 1 across the plasma membrane, without the movement of Cl−, making transport electroneutral (Choi et al., 2000; Parker et al., 2008). The Na+-driven Cl–HCO3 exchanger NDCBE appears to mediate the uptake of 1 Na+ and 2 ions, and the export of 1 Cl−, also making transport electroneutral (Wang et al., 2000).

In the present study, we freshly dissociated neurons from the MR and used immunocytochemical techniques to observe the presence of nNCBTs in neurons. We identified serotonergic neurons with a mouse monoclonal primary antibody directed against tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH), a 5HT neuronal marker. We identified GABAergic neurons using a mouse monoclonal antibody against glutamic acid decarboxylase 2 (GAD2), a GABA neuronal marker. In both cases, we then co-labeled with rabbit polyclonal antibodies directed against NBCn1, NDCBE, and NBCn2. The purpose of our study was to determine the expression of individual nNCBT proteins in serotonergic (vs. non-serotonergic) neurons and in GABAergic (vs. non-GABAergic) neurons of the MR. Following an increase in [CO2], the presence of nNCBTs in chemosensitive neurons would tend to promote the recovery of pHi from the intracellular acid load and thereby reduce the low-pHi stimulus for increased ventilation. Thus, one might hypothesize that nNCBTs are less abundant in chemosensitive neurons of the MR than in other neurons. However, we found that nNCBT expression frequencies do not differ substantially in serotonergic vs. other neurons, or in GABAergic vs. other neurons.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Freshly dissociated mouse neurons

Neurons were freshly dissociated from mice using approaches similar to those described by Kay and Wong (1986) and implemented by Bevensee et al. (1996) and Chen et al. (2008b). The usage of animals was performed according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Case Western Reserve University. Every effort was made to minimize the number of animals used and their suffering. Mice—approximately 7–33 weeks old of both sexes (thirteen males, seven females)—were decapitated, the brainstem isolated, and the MR dissected employing the basic approach used previously to obtain MR tissue from 12 to 18-day-old rats (Bradley et al., 2002; Wu et al., 2008). From the ventral surface of the mouse medulla (in the ventral medial medulla containing raphe magnus, pallidus, and obscures), we removed a section of tissue ~2 mm wide (centered at the midline), extending ~2 mm deep into the medulla, and extending ~4 mm along the length of the medulla (centered at the rostral–caudal midpoint). The tissue was placed in a 250 mL beaker of HEPES-buffered saline (HBS) solution, containing 130 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM dextrose, titrated to pH 7.3 with NaOH, and continuously bubbled with 100% O2 at room temperature. All subsequent manipulations were carried out at room temperature. After 10 min, the tissue was aspirated into a disposable transfer pipette and transported to a 10 mL 0.05–0.1% trypsin (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, type XI: bovine pancreas, T1005-1G) digestion solution at room temperature. After 10 min, we triturated the tissue in HBS—using a series of Pasteur pipettes with decreasing tip diameter—until cloudy. After trituration, neurons were suspended in neurobasal media (GIBCO BRL, Life Technologies Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA, cat# 21103) supplemented with B27. Cells were diluted to a concentration of ~1 × 105 cells/ml and placed on 18-mm-gridded glass coverslips treated with poly-l-ornithine. We allowed the cells to adhere to the glass for at least 60 min before fixing them in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) × 20 min.

ePet-enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP) mice

We used the ePet-EYFP transgenic mouse (Scott et al., 2005)—in which 5HT neurons fluoresce—as positive controls for identifying serotonergic neurons in the MR.

nNCBT-knockout (KO) mice

As negative controls to test the selectivity of the rabbit polyclonal antibodies directed against the transporters, we freshly dissociated neurons from the MR of mice deficient in a single nNCBT.

NBCn1 (slc4a7) KO mice

We thank Christian Aalkjaer (Aarhus University, Denmark) for these mice. They were generated using a gene-trap technique that resulted in the insertion of the LacZ gene into the slc4a7 gene (Boedtkjer et al., 2008).

NDCBE (slc4a8) KO mice

We thank Christian Hübner (Institute for Clinical Chemistry, University Hospital Jena, Friedrich Schiller Universität, Jena, Germany) for these mice. They were generated by deleting exon 12 (Leviel et al., 2010).

NBCn2 (slc4a10) KO mice

These mice were also provided by Christian Hübner, which were generated by deleting exon 12, which results in a frameshift and premature termination within exon 13 (Jacobs et al., 2008).

All three KO strains—in a C57BL/6J background—were transferred to our laboratory, which we then backcrossed for at least five generations for NBCn1 and NBCn2, and three generations for NDCBE with our standard C57BL/6 strain.

Antibodies

Microtubule associated protein-2 (MAP2)

We used MAP2 as a CNS neuronal cell marker. An anti-MAP2 (mouse monoclonal IgG1, clone AP20) was obtained from Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA. It was detected with a goat-anti-mouse IgG1 antibody tagged with Cyanine 2, obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA.

TPH

We used TPH to identify serotonergic (5-hydroxy-l-tryptophan, 5-HTP) neurons. An anti-TPH antibody (mouse monoclonal IgG3, clone WH-3) was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO. It was detected with a goat-anti-mouse IgG3 antibody tagged with Cyanine 5, obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.

GAD2

We used GAD2 as a marker for GABAergic neurons. An anti-GAD2 antibody (mouse monoclonal IgG3, clone 26H1, directed against the GAD65, the 65 kDa isoform) was purchased from SySy, Goettingen, Germany. It was detected with a goat-anti-mouse IgG3 antibody tagged with Cyanine 5, obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.

NBCn1

We detected this nNCBT with an anti-NBCn1 polyclonal rabbit antibody against the predicted 87-residue carboxy-terminus (Ct) of NBCn1-A (Chen et al., 2007). This antibody could in principle recognize all known variants of NBCn1 (Boron et al., 2009; Parker and Boron, 2013).

NDCBE

We identified this nNCBT with a rabbit polyclonal antibody against the first 18 amino-acid residues of the cytosolic amino-terminus (Nt) of NDCBE-A and -B. The antibody had been affinity purified (CarboxyLink Kit, cat# 44899, Thermoscientific, Rockford, IL, USA) and characterized previously (Chen et al., 2008a). This anti-NDCBE antibody does not recognize NDCBE-C or -D (Parker and Boron, 2013).

NBCn2

We detected this nNCBT with an affinity purified rabbit polyclonal antibody against the first 18 amino acids of its Nt terminus (Liu et al., 2010). This antibody recognizes all four variants of NBCn2 (Parker and Boron, 2013).

All rabbit polyclonal antibodies were detected with a goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody coupled to horseradish peroxidase (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH, USA) and was visualized by tyramide amplification using the TSA plus Tetramethylrhodamine System reagent (cat# NEL742001KT, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA).

Immunocytochemistry

Freshly dissociated neurons on coverslips were fixed in 4% PFA and washed 6 × 5 min with Tris-buffered saline (TBS) with 0.05% Tween-20 (TBST). The cells were then treated in 5% normal goat serum (NGS) in TBS × 1 h at room temperature to minimize nonspecific binding and subsequently incubated overnight at 4 °C with one or more primary antibodies: anti-MAP2 at 1:100, anti-TPH at 1:100, and anti-GAD2 at 1:200 dilution to identify cell types. In all cases, the antibodies were diluted in TBS containing 2.5% NGS, and 0.025% Triton X-100. After the overnight incubation with the primary antibodies, the cells were rinsed with TBST and again treated in NGS ×1 h and then washed with TBST. The samples then were incubated ×1 h with fluorescent-tagged goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies:Cyanine-2-tagged anti-IgG1, and Cyanine-5-tagged anti-IgG3. In each case, the dilution of the secondary antibody was 1:500 in TBS containing 2.5% NGS, and 0.025% Triton X-100 at room temperature. After the incubation, the samples were rinsed 6× 5 min with TBST and counterstained with the nuclei marker DAPI, at 1:10 dilution and mounted on microscope slides using Fluorshield (cat# F6057, Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

The above protocols were slightly modified when using antibodies directed against the nNCBTs. After PFA fixation, we treated the coverslips with 0.3% H2O2—to eliminate endogenous peroxidase activity—in TBS ×5 min. As above, the cells were then washed with TBST ×6, followed by blocking with 5% NGS in TBS ×1 h. One at a time, the nNCBTs were identified by rabbit polyclonal IgG primary antibodies: anti-NBCn1 at 1:1200, anti-NBCn2 at 1:100, or anti-NDCBE at 1:1000. The nNCBT antibodies were diluted in TBS containing 2.5% NGS, and 0.025% Triton X-100 overnight at 4 °C. For colabeling, cell-type specific primary antibodies (anti-MAP2, -TPH, -GAD2) were co-incubated with the different anti-nNCBTs. After the antibody incubation, the coverslips were treated as above with 5% NGS ×1 h and then washed with TBST. The cells were incubated with the secondary antibody: goat-anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-tagged IgG at 1:400 dilution in TBS containing 2.5% NGS, and 0.025% Triton X-100 at room temperature ×1 h. When co-labeling, we simultaneously incubated with the goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies described above. We then rinsed with TBST ×6 for 5 min each and treated the cells with the signal amplification reagent TSA plus Tetramethylrhodamine System at 1:100 dilution. Finally, the cells were counterstained with DAPI and mounted by Fluorshield on microscope slides as described above.

Confocal microscopy

An Olympus FV1000 (IX81) laser scanning confocal microscope was used to visualize the fluorophore-tagged secondary antibodies. Images of specimens were collected at different wavelengths to view multiple antibodies. For co-labeling studies, scanning with each laser line was done separately to minimizing bleed-through, which was negligible. Z-stack images (ranging from 50 to 500-nm per slice) were acquired utilizing the full dynamic range of the acquisition system, that is, settings of laser intensity, PMT voltage and offset were based upon laser wavelength and intensity of specimen fluorophores. Images were sampled at 12 bits/pixel and a dwell time of 8.0 μs/pixel. Differential interference contrast (DIC) images were acquired together with the fluorescent ones, using the transmitted light of one of the laser lines.

Image analysis

To distinguish between signal and unspecific staining, regions of neuronal and non-neuronal cells were selected from Z-stack “max projections” and the images converted to masks outlining the cells. The masks were applied to the original images to retain pixel intensities of the cells, but to set the extracellular background to zero. The mean pixel intensity of the cell (arbitrary intensity units or a.u.) was calculated from the sum of all pixel intensities within the cell region divided by the cell area obtained from the mask.

A 3-dimensional image was generated from the Z-stack, and is described by the x–y–z coordinate system. The x-axis shifts from front-to-back, the y-axis shifts from left-to-right, and the z-axis shifts from top-to-bottom. A “z-section” produced from our z-stack allows us to view an image from the yz-plane and xz-plane.

Microscope settings and thresholds for viewing remained constant for all images (depending on the antibody) to allow comparisons between control images and experimental samples.

RESULTS

We freshly dissociated cells onto coverslips and exposed these separately to mouse monoclonal antibodies directed against markers for neurons (i.e., MAP2) or neuronal subtypes (i.e., TPH and GAD2). We identified the electroneutral NCBTs using rabbit polyclonal antibodies directed against each of the transporters (i.e., NBCn1, NDCBE, NBCn2). For each antibody, we recorded frequency distributions (number of pixels vs. pixel intensity) for several cells, using positive controls (i.e., ePet-EYFP mice) and negative controls (i.e., omission of primary antibody or use of KO mouse) to establish intensity thresholds to determine whether a cell was positive or negative for the antibody.

Neuronal cell types identified in the MR

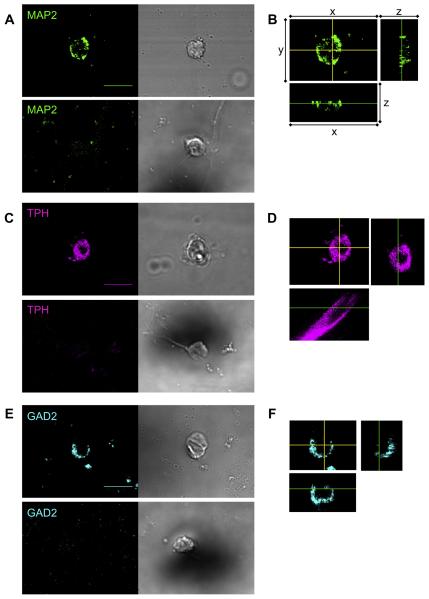

Images of cells identified with MAP2, TPH, and GAD2 antibodies

We used specific antibodies to differentiate between neurons and non-neurons and also recognized potentially chemosensitive neurons. The IgG1-specific MAP2 monoclonal antibody identified neurons within the MR (Fig. 1A, upper left panel). As a negative control, we eliminated the MAP2 antibody (Fig. 1A, lower left). We also acquired DIC images (Fig. 1A, right panels) in addition to the fluorescent images to facilitate the identification of negative cells. We distinguished MAP2-positive cells from MAP2-negative cells based on the striking difference on observed intensity. MAP2 is localized to the cytoplasm and is non-nuclear (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Identification of neuronal cell types in the MR, using mouse monoclonal antibodies. (A) The IgG1 monoclonal MAP2 antibody, together with the Cyanine-2-tagged anti-IgG1 secondary antibody (green), identifies a neuron (upper left panel) that is also shown in a DIC image (upper right). In the absence of the primary antibody, the secondary antibody did not recognize any cells, one example of which is shown here as a negative control (lower left). The DIC image shows the cell at this location (lower right). (B) Representative z-sections for neuron on left side of panel A (details below). (C) The IgG3 monoclonal TPH antibody, together with the Cyanine-5-tagged anti-IgG3 secondary antibody (magenta), identifies a serotonergic neuron (upper left panel). The staining of the secondary antibody is virtually eliminated in the absence of the primary antibody (lower left panel). The two right panels show the DIC images. (D) Representative z-sections for neuron on left side of panel C (details below). (E) IgG3 monoclonal GAD2 antibody, together with the Cyanine-5-tagged anti-IgG3 secondary antibody (cyan), identifies a GABAergic neuron (upper left panel). The staining of the secondary antibody is virtually eliminated in the absence of the primary antibody (lower left panel). The two right panels show the DIC images. Details on z-sections (panels B, D, F): For each, the main picture is an xy section (MAP2 500 nm/slice; TPH 60 nm/slice; GAD2 235 nm/slice) per slice. The yellow cross-hairs indicate the planes of the two side views: the xz section (shown below the main picture) and the yz section (shown to the right of the main picture). In the xz and yz sections, the green lines show the plane of the xy section. Scale bar = 10 μm. Images were acquired with a 60× objective. These panels show that the MAP2, TPH, and GAD2 antibodies are within the cytoplasm but excluded from the nucleus. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

We identified serotonergic neurons using a specific TPH antibody (Fig. 1C, upper left). Again, as a negative control, we eliminated the primary antibody (Fig. 1C, lower left). The TPH enzyme is within the cytoplasm and non-nuclear (Fig. 1D).

Finally, in a separate incubation, we used a specific GAD2 antibody to identify GABAergic neurons in the MR (Fig. 1E, upper left), eliminating the primary antibody as the negative control (Fig. 1E, lower left). GAD2 is present in the cytoplasm and absent in the nucleus (Fig. 1F).

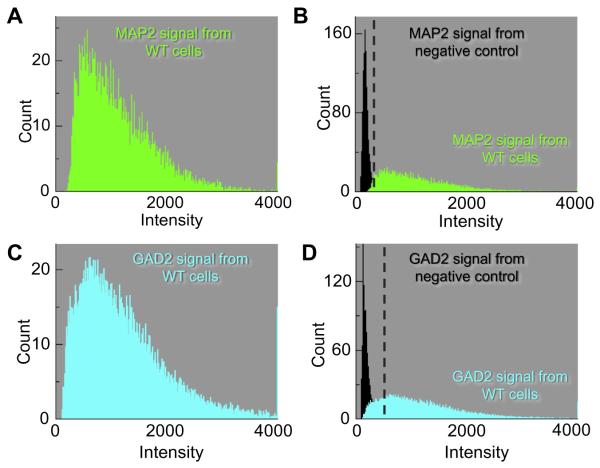

Frequency distributions of pixel intensities for MAP2- and GAD2-positive cells

We recorded the mean frequency distribution of pixel intensities for a small population of neurons for each group, and from that computed the mean intensity. For the 10 MAP2-positive cells (Fig. 2A), the average mean intensity was 876 ± 161 (SEM) arbitrary units (a.u.), with a range of 520–1533 (Table 1). The 10 negative control cells (Fig. 2B)—those with primary antibody absent—had an average mean intensity of 177 ± 14 (a.u.), with a range of 164–194 (Table 1). As a threshold for distinguishing positive from negative cells, we chose the midpoint between the cell with the highest negative mean (194) and the cell with the lowest positive mean (520), which is approximately 357 (a.u.). Thus, cells with a mean pixel intensity >357 (a.u.) we will regard as MAP2 positive, and cells with mean pixel intensities <357 (a.u.) we will regard as MAP2 negative.

Fig. 2.

Frequency distributions of the individual cell types. The data summarized here come from many images like that in Fig. 1. (A) The mean frequency distribution (green histogram) of 10 MAP2-positive cells describes the average number of pixels for each pixel intensity. The mean intensity of cells in the MAP2 population was 876 (arbitrary units, a.u.). (B) The frequency distribution of the negative controls (black histogram) is the average of 10 cells. The average mean intensity from negative controls was 177 (a.u.). The green data represent a re-plot of the data from panel A. (C) The mean frequency distribution (Cyan histogram) of 13 GAD2-positive cells yields a mean intensity of 1175 (a.u.). (D) The frequency distribution of the negative controls (black histogram) is an average of 20 cells. The average mean intensity from negative controls was 220 (a.u.). The cyan data represent a re-plot of the data from panel C. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Table 1.

Signal intensities from fluorescent markers (in arbitrary units)

| Mean | Standard deviation | Standard error | Range | Midpoint (threshold) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAP2 (n = 10) | 876 | 509 | 161 | 520–1533 | 357 |

| MAP2 (−1° Ab) (n = 10) | 177 | 43 | 14 | 164–194 | |

| GAD2 (n = 13) | 1175 | 300 | 83 | 841–1845 | 579 |

| GAD2 (−1° Ab) (n = 20) | 202 | 67 | 15 | 138–317 | |

| TPH positive (ePet-EYFP mouse) (n = 34) | 1480 | 704 | 121 | 909–3936 | 896 |

| TPH negative (ePet-EYFP mouse) (n = 71) | 477 | 222 | 26 | 120–884 | |

| TPH (−1° Ab) (n = 11) | 125 | 27 | 8 | 105–193 | |

| nNCBTs (−1° Ab) (n = 10) | 570 | 78 | 25 | 399–660 | |

| NBCn1 (n = 14) | 2044 | 474 | 127 | 1272–2928 | 943 |

| NBCn1-KO (n = 11) | 514 | 84 | 25 | 293–614 | |

| NDCBE (n = 15) | 1400 | 302 | 78 | 982–1980 | 766 |

| NDCBE-KO (n = 9) | 370 | 79 | 26 | 285–549 | |

| NBCn2 (n = 15) | 1499 | 479 | 124 | 1116–2514 | 748 |

| NBCn2-KO (n = 10) | 294 | 62 | 63 | 214–380 |

Using a similar approach, we identified 13 GAD2-positive cells and recorded the frequency distribution (Fig. 2C). These had an average mean intensity of 1175 ± 83 (a.u.), with a range of 841–1845 (Table 1). The 20 control cells (Fig. 2D) had an average mean intensity of 202 ± 15 (a.u.), with a range of 138–317 (Table 1). The midpoint value between the highest negative mean (317) and the lowest positive mean (841), is approximately 579 (a.u.). Thus, cells with mean pixel intensities >579 (a.u.) we will regard as GAD2 positive.

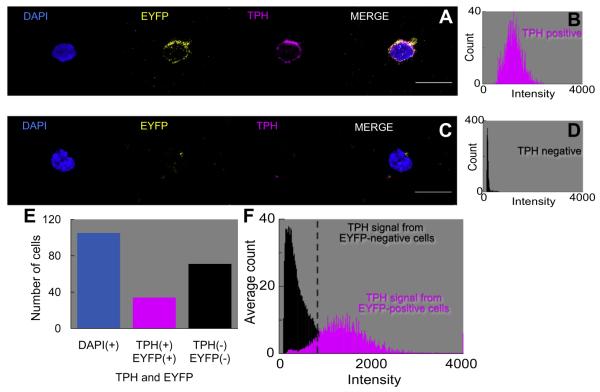

Identification of serotonin neurons using EYFP fluorescence vs. TPH antibody

Our approach was to use EYFP-positive and EYFP-negative cells—isolated from the MR of ePet-EYFP transgenic mice—as positive and negative controls, respectively, for identifying serotonergic neurons. After fixing the cells, we incubated them with the TPH antibody. Finally, to identify all nuclei, we counterstained with DAPI. Fig. 3A shows a neuron that is positive for DAPI, EYFP, and TPH. The rightmost panel in Fig. 3A is a merge of the three previous panels. Fig. 3B is a frequency distribution of the mean pixel intensity in the TPH panel of the neuron shown in Fig. 3A. Fig. 3C shows a cell that was DAPI positive, but TPH negative and EYFP negative; as expected the frequency distribution for the TPH signal in Fig. 3D reveals a low mean intensity.

Fig. 3.

Co-localization of TPH antibody with EYFP-tagged neurons in the MR. (A) The DAPI marker (blue) identifies the nucleus of the cell in the first panel. The ePet-EYFP tag (yellow) identifies a serotonergic neuron in the second panel. In the third panel, the IgG3 monoclonal TPH antibody, together with the Cyanine-5-tagged anti-IgG3 secondary antibody (magenta), identifies the cell as a serotonergic neuron. In the fourth panel, the merge is an assembly of all of the images. (B) Frequency distribution of the TPH antibody (magenta histogram) for the TPH cell in panel A, which we consider a 5HT-positive neuron. The mean pixel intensity is 1236 (a.u.). (C) The DAPI marker identifies the nucleus, the EYFP tag is negative, the TPH antibody is negative, and the merge is an assembly of all of the images. (D) The frequency distribution of the TPH antibody (black histogram) for the TPH cell in panel C, which we consider a 5HT-negative cell. The mean pixel intensity is 178 (a.u.). (E) Summary of the total counts of cells: 105 DAPI+, 34 EYFP+/TPH+, 71 EYFP−/TPH−. (F) Mean frequency distribution of the TPH signal (magenta histogram) in 34 EYFP+/TPH+ cells. The mean intensity is 1480 (a.u.). Mean frequency distribution of the TPH signal (black histogram) in 71 EYFP−/TPH− cells. The mean pixel intensity is 477 (a.u.). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

We examined 105 neurons in this study, and determined by eye whether each neuron was EYFP positive or negative. Of the 105 cells, 34 were EYFP positive (Fig. 3E); these had an average TPH mean intensity of 1480 ± 121, with a range of 909–3936 (Table 1). Of the 105 cells, the other 71 cells were EYFP negative (Fig. 3E) and had an average TPH mean intensity of 477 ± 26, with a range of 120–884 (Table 1). Using an approach similar to the one applied to MAP2 above, we assigned a threshold a mean pixel intensity >896 (a.u.)—that is, the midpoint of the highest negative mean and the lowest positive mean—to distinguish TPH-positive vs. -negative cells. In other experiments on cells isolated from wild-type mice (WT; data not shown), we eliminated the primary TPH antibody. The 10 MR cells examined in these experiments yielded a low TPH mean intensity of 125 ± 8 (Table 1).

We observed a 100% concordance between the EYFP and TPH approaches for determining whether cells were serotonergic. The magenta histogram in Fig. 3F summarizes the mean frequency distribution of TPH intensities for the 34 EYFP-positive/TPH-positive neurons, which we will regard as serotonergic (34/105 = 32% of all cells). The black histogram in Fig. 3F summarizes the mean frequency distribution for 71 EYFP-negative/TPH-negative cells, which we will regard as non-serotonergic.

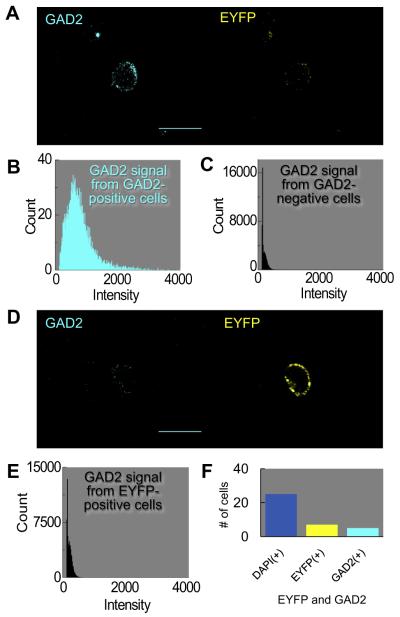

Mutual exclusivity of GAD2 and EYFP signal

In principle, no GAD2-positive cells should have been TPH positive or vice versa. To test this hypothesis, we incubated the GAD2 antibody with cells freshly dissociated from the MR of ePet-EYFP mice. Fig. 4A shows a cell that is GAD2 positive (cyan) but EYFP negative (yellow). The histogram in Fig. 4B shows the average frequency distribution of five GAD2-positive cells, all of which were EYFP negative. The average mean intensity for the five GAD2-positive cells was 689 ± 52 (a.u.), with a range of 583–868. The histogram in Fig. 4C represents data for 20 cells that were GAD2 negative. The average mean pixel intensity for the 20 GAD2-negative cells was 221 ± 13 (a.u.), with a range of 141–337. Fig. 4D shows a cell that is GAD2 negative (cyan) but EYFP positive (yellow). The histogram in Fig. 4E represents the average frequency distribution of the GAD2 signal in seven EYFP-positive cells, all of which were GAD2 negative. These seven cells are a subset of the 20 GAD2-negative neurons summarized in Fig. 4C. The average mean pixel intensity of 253 ± 26 (a.u.) and range of 145–337 of these seven cells were similar to those of the other populations of GAD2-negative cells noted earlier. In summary, of cells freshly dissociated from ePet-EYFP mice, five out of 25 (20%) were GAD2 positive and seven out of the 25 cells (28%) were EYFP positive (Fig. 4F), with no overlap in the two populations.

Fig. 4.

Mutual exclusivity of GAD2 antibody and EYFP-tagged neurons in the MR. (A) GABAergic neuron. The GAD2 antibody (cyan) identifies a GABAergic neuron, whereas the EYFP tag (yellow) is negative. (B) The mean frequency distribution of the GAD2 signal in 5 GAD2-positive cells (cyan histogram, left panel). Of 5 GAD2-positive cells, 0 were EYFP positive. The mean intensity is 689 (a.u.). (C) The mean frequency distribution of the GAD2 signal in 20 GAD2-negative cells (black histogram, right panel). The mean pixel intensity is 220 (a.u.). (D) Serotonergic neuron. (D) The GAD2 antibody does not label the cell, but the EYFP tag is positive. Of the 7 EYFP-positive cells, 0 were GAD-positive. (E) The mean frequency distribution of the GAD2 signal in 7 EYFP-positive cells. The mean pixel intensity is 253 (a.u.). (F) Summary of total counts of cells: 25 DAPI+, 5 EYFP−/GAD2+, and 7 EYFP+/GAD2−. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

nNCBTs identified in the MR

Subcellular localization of transporters

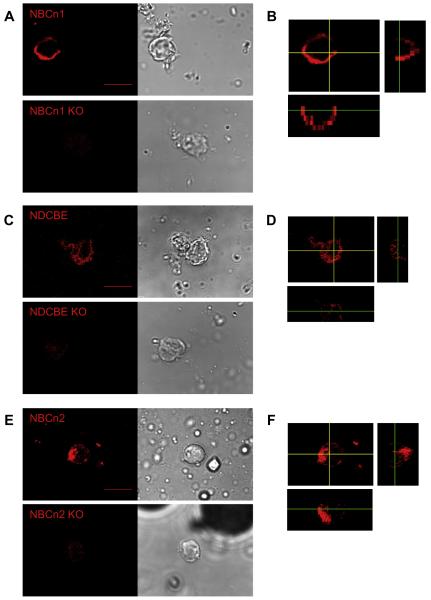

We examined the presence of the nNCBTs in MR cells, using rabbit polyclonal antibodies directed against the transporters in separate incubations. We identified, by eye, cells that appeared positive for NBCn1 (slc4a7) from freshly dissociated WT mice (Fig. 5A, upper left panel). As a definitive negative control, we incubated the NBCn1 antibody with cells freshly dissociated from NBCn1-null mice (Boedtkjer et al., 2008). The NBCn1 antibody is barely visible in NBCn1-KO cells (Fig. 5A, lower left). The DIC images are on the right of Fig. 5A. Fig. 5B is a z-section of the NBCn1-positive cell shown in Fig. 5A. We can determine from the z-sections that NBCn1 is non-nuclear and within the cytoplasm or cell membrane. The NDCBE (slc4a8) antibody—which should react with NDCBE-A/B but not NDCBE-C/D (Chen et al., 2008a)—identified cells from WT but not NDCBE-null mice (Fig. 5C). NDCBE is non-nuclear and within the cytoplasm or cell membrane (Fig. 5D). Lastly, the NBCn2 (slc4a10) antibody reacted robustly with WT but not NBCn2-null MR cells (Fig. 5E). As was the case for the NBCn1 and NDCBE antibodies, it was relatively excluded from the nucleus but present in the cytoplasm or plasma membrane (Fig. 5F).

Fig. 5.

Individual labeling of SLC4A transporters, using rabbit polyclonal antibodies. (A) The IgG polyclonal NBCn1 antibody—together with the horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-tagged IgG antibody, followed by signal amplification using the Tetramethylrhodamine (TMR) System (red)—identifies NBCn1 in a cell from a WT mouse (upper left panel). In cells from an NBCn1-KO mouse, we detect only a very faint signal (lower left panel). The two right panels show the corresponding DIC images. (B) Representative z-sections (for details, see legend of Fig. 1) for cell on left side of panel A (xy sections, 1230 nm). (C) The IgG polyclonal NDCBE antibody likewise identifies NDCBE in a cell from a WT mouse (upper left panel). We detect only a very faint signal from a cell from an NDCBE-KO mouse (lower left panel). The two right panels show the DIC images. (D) Representative z-sections for cell on the left side of panel C (xy sections, 360 nm). (E) The IgG polyclonal NBCn2 antibody likewise recognizes NBCn2 in a cell from a WT mouse (upper left panel). In cells from an NBCn2-KO mouse, the signal is extremely faint (lower left panel). The two right panels show the DIC images. (F) Representative z-sections for cell on left side of panel E (xy sections, 410 nm). Scale bar = 10 μm. Images were acquired with a 60× objective. These panels show that the NBCn1, NDCBE, and NBCn2 antibodies are within the cytoplasm, and presumably the cell membrane, but excluded from the nucleus. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Frequency distributions of pixel intensities

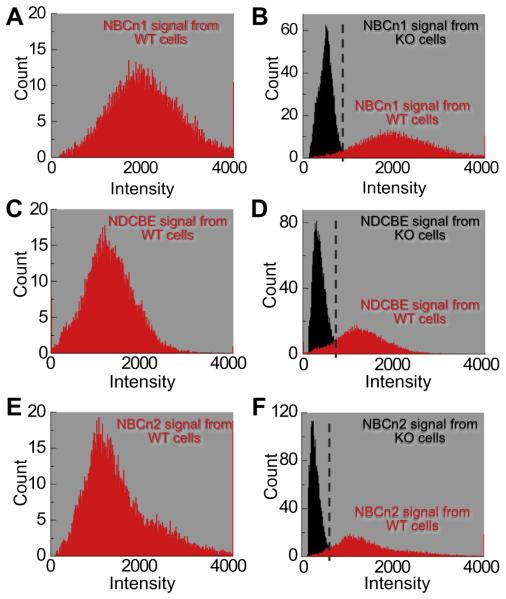

NBCn1

For neurons like those shown in Fig. 5, we generated frequency distributions for cells isolated from WT (Fig. 6, left) and KO mice (Fig. 6, right). Fig. 6A shows the mean frequency distribution of 14 MR cells judged by eye to be positive for NBCn1. For individual cells, the mean intensities averaged 2044 ± 127 (a.u.), and ranged from 1272 to 2928 (Table 1). For 11 NBCn1-KO cells, the average mean intensity was 514 ± 84 (a.u.); for individual cells, the means had a range of 293–614 (Fig. 6B, Table 1). The midpoint between the highest mean from KO cells and the lowest mean from WT cells was approximately 943 (a.u.). Thus, cells with a mean pixel intensity >943 (a.u.) we will regard as NBCn1 positive, and cells with a mean pixel intensity <943 (a.u.) we will regard as NBCn1 negative.

Fig. 6.

Frequency distributions of the nNCBTs. The data summarized here come from many experiments like that in Fig. 5. (A) The mean frequency distribution (red histogram) from 14 NBCn1-positive cells describes the average number of pixels for each pixel intensity. The mean intensity from cells in the NBCn1 population was 2044 (a.u.). (B) The frequency distribution of negative controls (black histogram) is an average of 11 cells from NBCn1-KO mice. The average mean intensity from NBCn1-KO cells was 514 (a.u.). The red data in panel B are the same data as in panel A. (C) The frequency distribution (red histogram) from 15 NDCBE-positive cells yields a mean intensity of 1400 (a.u.). (D) The frequency distribution of negative controls (black histogram) is an average of nine cells from NDCBE-KO mice. The average mean intensity from NDCBE-KO cells was 370 (a.u.). The red data in panel D are the same data as in panel C. (E) The frequency distribution (red histogram) from 15 NBCn2-positive cells yields a mean intensity of 1499 (a.u.). (F) The frequency distribution of negative controls (black histogram) is an average of 10 cells from NBCn2-KO mice. The average mean intensity from NBCn2-KO cells was 294 (a.u.). The red data in panel F are the same data as in panel E. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

NDCBE

We determined the mean frequency distribution of 15 WT MR cells that appeared by eye to be positive for NDCBE (Fig. 6C). The mean intensities of individual cells averaged 1400 ± 78 (a.u.) and ranged from 982 to 1980 (Table 1). Among nine NDCBE-KO cells, the mean intensities of individual cells averaged 370 ± 26 (a.u.), ranging from 285 to 549 (Fig. 6D, Table 1). The midpoint value between the highest mean from NDCBE-KO cells (549) and the lowest mean from NDCBE WT cells (982) was approximately 766 (a.u.). Therefore; cells with a mean pixel intensity >766 (a.u.) we will regard as NDCBE positive.

NBCn2

Finally, we recorded the frequency distribution of 15 MR cells judged by eye to be NBCn2-positive cells. For individual cells, mean intensity averaged 1499 ± 124 (a.u.), ranging from 1116 to 2514 (Fig. 6E). The comparable figures for 10 individual NBCn2-KO cells were an average mean intensity of 294 ± 63 (a.u.), and means ranging from 214 to 380. The midpoint value between the highest mean from NBCn2-KO cells (380) and the lowest mean from NBCn2 WT cells (1116) was approximately 748 (a.u.). We will regard cells with a mean pixel intensity >748 (a.u.) as NBCn2 positive.

Co-labeling of neuronal cell types and nNCBTs

In these experiments, we co-labeled cells with monoclonal antibodies that detect specific cell types and polyclonal antibodies directed against individual transporters. We calculated the percentage of neurons (identified with the MAP2 antibody) that were either TPH positive or GAD2 positive or neither. We also determined the fraction of TPH-positive and GAD2-positive neurons that were also positive for NBCn1, for NDCBE, and for NBCn2.

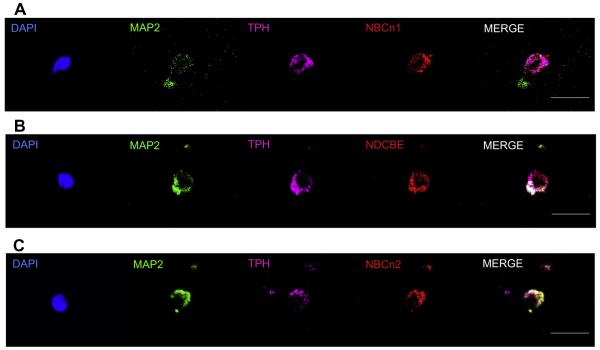

Serotonergic neurons: expression of nNCBTs

Fig. 7 shows images of three representative serotonergic neurons freshly dissociated from the mouse MR. DAPI (blue) recognizes the nucleus, the MAP2 (green) antibody identifies the cell as a neuron, the TPH antibody (magenta) identifies specifically serotonergic neurons, the three nNCBT antibodies (red) identify individual transporters, and the merge assembles all the images. We can conclude that at least some serotonergic neurons express NBCn1 protein (Fig. 7A) or NDCBE protein (Fig. 7B) or NBCn2 protein (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 7.

Co-labeling studies of serotonergic neurons with nNCBT antibodies. (A) NBCn1. The DAPI marker (blue) identifies the nucleus within a cell (see Fig. 3). The IgG1 mouse monoclonal MAP2 antibody (green) identifies the cell as a neuron (see Fig. 1). The IgG3 mouse monoclonal TPH antibody (magenta) identifies the neuron as a serotonergic neuron (see Fig. 1 and Fig. 3). The IgG rabbit polyclonal antibody (red) identifies NBCn1 within the neuron (Fig. 5). The merge (white) is an assembly of all panels except DAPI. Thus, the cell is a serotonergic neuron that contains the NBCn1 transporter (B) NDCBE. The cell stains positive for DAPI, MAP2, TPH, and NDCBE. (C) NBCn2. The cell stains positive for DAPI, MAP2, TPH, and NBCn2. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

NBCn1

In a population of freshly dissociated cells, 49 were DAPI-positive, 42 were MAP2 positive, indicating 86% of cells in this series were neurons (Table 2). Of the 42 MAP2-positive cells, 15 were TPH positive, meaning 36% of neurons were serotonergic (Table 2).

Table 2.

Frequency distribution of neuronal subtypes and nNCBTs

| Marker | Cell count | Percent (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| DAPI | 49 | 100 | Fig. 8 |

| MAP2 | 42 | 84 | |

| TPH | 15 | 32 | |

| NBCn1 | 42 | 84 | |

| DAPI | 48 | 100 | Fig. 8 |

| MAP2 | 43 | 90 | |

| TPH | 7 | 15 | |

| NDCBE | 47 | 98 | |

| DAPI | 50 | 100 | Fig. 8 |

| MAP2 | 41 | 82 | |

| TPH | 13 | 18 | |

| NBCn2 | 48 | 96 | |

| DAPI | 46 | 100 | Fig. 10 |

| MAP2 | 40 | 87 | |

| GAD2 | 16 | 35 | |

| NBCn1 | 43 | 93 | |

| DAPI | 55 | 100 | Fig. 10 |

| MAP2 | 47 | 85 | |

| GAD2 | 17 | 31 | |

| NDCBE | 48 | 87 | |

| DAPI | 47 | 100 | Fig. 10 |

| MAP2 | 41 | 87 | |

| GAD2 | 15 | 32 | |

| NBCn2 | 43 | 91 |

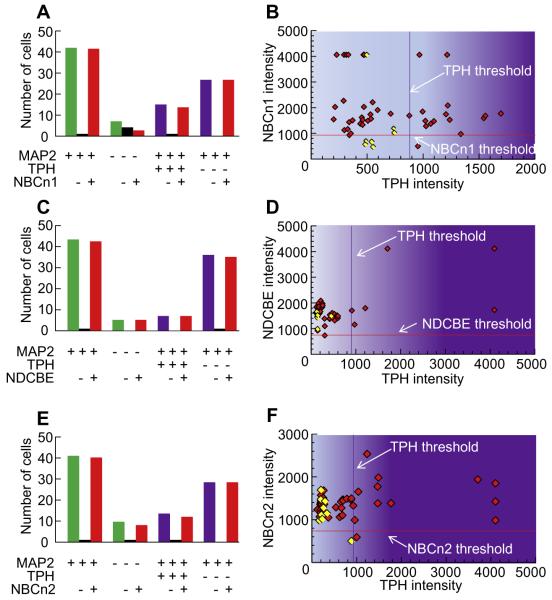

Fig. 8A summarizes the NBCn1 status of MAP2-positive vs. MAP2-negative cells, as well as for TPH-positive vs. TPH-negative neurons. Of all neurons, 98% were NBCn1 positive (41 NBCn1+/42 MAP2+), 43% of non-neurons were NBCn1 positive (3 NBCn1+/7 MAP2−), 93% of TPH neurons were NBCn1 positive (14 NBCn1+/15 TPH+), and 100% of non-TPH neurons were also NBCn1 positive (27 NBCn1+/27 TPH−MAP2+).

Fig. 8.

Summary of data on the co-labeling of nNCBTs and TPH. The data summarized here come from many experiments like that in Fig. 7. (A) Summary of the total counts of cells in NBCn1 study. The legend beneath the bars indicates whether the cells were positive (+), negative (−), or either (blank cell) for MAP2, TPH, and NBCn1. Thus, the left-most group of three bars indicates that we analyzed 42 MAP2+ cells, one of which was NBCn1−, and 41 of which were NBCn1+. (B) The scatter diagram describes the relationship between the intensities of the NBCn1 signal and TPH signal. Each diamond represents one MAP2+ (red) or MAP2− (yellow) cell. (C) Summary of the total counts of cells in NDCBE study. (D) The scatter diagram describes the relationship between the intensities of the NDCBE signal and TPH signal. (E) Summary of the total counts of cells in NBCn2 study. (F) The scatter diagram describes the relationship between the intensities of the NBCn2 signal and TPH signal. Based on simple linear regression, the coefficient of determination R2 was <0.06 in panels B and F, and <0.46 in panel D. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 8B is a scatter diagram that describes the relationship between NBCn1 expression on the y axis (based upon mean intensity of individual cells) and TPH expression on the x axis.

Fig. 8B confirms that the overwhelming majority of all neurons are NBCn1 positive but that the odds of a neuron being NBCn1 negative are similar in TPH-negative cells (0%, left side of plot) and in TPH-positive cells (7%, right side of plot).

NDCBE

In a second population of freshly dissociated cells, 90% were neurons (43 MAP2+/48 DAPI+), and 15% of neurons in this sample were serotonergic (7 TPH+/43 MAP2+; Table 2). Of the total neuronal population, 98% were NDCBE positive (42 NDCBE+/43 MAP2+), 100% of non-neurons were NDCBE positive (5 NDCBE+/5 MAP2−), 100% of TPH neurons were NDCBE positive (7 NDCBE+/7 TPH+), and 97% of non-TPH neurons were NDCBE positive (35 NDCBE+/36 TPH− MAP2+; Fig. 8C). The scatter diagram in Fig. 8D confirms that nearly all cells are positive for NDCBE, but more importantly all TPH-positive neurons examined contain NDCBE. Thus, the odds of a cell being NDCBE positive are about the same regardless of whether it is TPH positive (100%, right side of plot) or TPH negative (97%, left side of plot).

NBCn2

In a third population of freshly dissociated cells, 82% were neurons (41 MAP2+/50 DAPI+), and 32% of neurons were serotonergic (13 TPH+/41 MAP2+; Table 2). In Fig. 8E, the bar graphs show that 98% of neurons in this population were NBCn2 positive (40 NBCn2+/41 MAP2+), 88% of non-neurons were NBCn2 positive (8 NBCn2+/9 MAP2−), 92% of TPH-positive neurons were NBCn2 positive (12 NBCn2+/13 TPH+), and 100% of non-TPH neurons were NBCn2 positive (28 NBCn2+/28 TPH− MAP2+). The scatter diagram in Fig. 8F confirms that nearly all cells are NBCn2 positive, so the odds of a cell being NBCn2-positive are similar regardless of whether the cell is TPH positive (92%, right side of plot) or TPH negative (100%, left side of plot).

GABAergic neurons

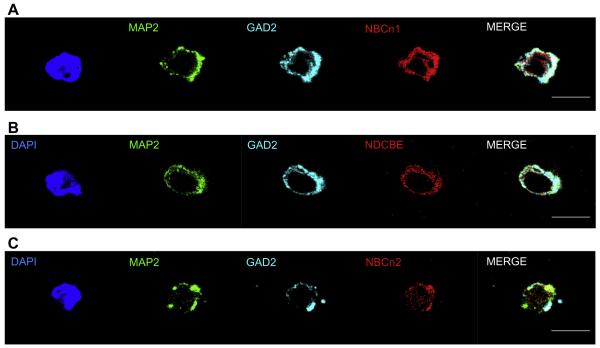

expression of nNCBTs. Analogous to the previous experiments on serotonergic neurons, we determined nNCBT expression in GABAergic neurons freshly dissociated from the MR by simultaneously incubating the coverslips with specific antibodies directed against GAD2 as well as one of the three nNCBTs. Fig. 9 shows images of cells recognized by DAPI (blue), MAP2 (green), nNCBTs (red), and GAD2 (cyan), indicating that GABAergic neurons of the MR can express NBCn1, NDCBE, and NBCn2.

Fig. 9.

Co-labeling studies of GABAergic neurons with nNCBT antibodies. (A) NBCn1. DAPI (blue) identifies the nucleus within a cell (see Fig. 3). The IgG1 mouse monoclonal MAP2 antibody (green) identifies the cell as a neuron (see Fig. 1). The IgG3 mouse monoclonal GAD2 antibody (cyan) identifies the neuron as a GABAergic neuron (see Figs. 1 and 4). The IgG rabbit polyclonal antibody (red) identifies NBCn1 within the neuron. The merge (white) is an assembly of all panels except DAPI. Thus, the cell is a GABAergic neuron that contains NBCn1. (B) NDCBE. The cell is positive for DAPI, MAP2, GAD2, and NDCBE. (C) NBCn2. The cell is positive for DAPI, MAP2, GAD2, and NBCn2. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

NBCn1

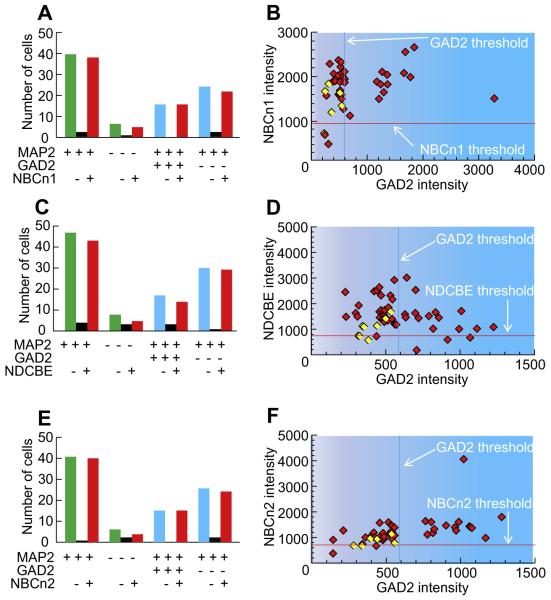

In one population of freshly dissociated cells from the MR, 87% were neurons (40 MAP2+/46 DAPI+), and 40% of these neurons were GABAergic (16 GAD2+/40 MAP2+; Table 2). The bar graphs in Fig. 10A summarize the NBCn1 status of MAP2-positive vs. MAP2-negative cells, as well as for GAD2-positive vs. GAD2-negative neurons. Of the total neurons, 95% were NBCn1 positive (38 NBCn1+/40 MAP2+). 83% of Non-neurons expressed NBCn1 (5 NBCn1+/6 MAP2−). 100% of the GAD2-positive neurons were NBCn1 positive (16 NBCn1+/16 GAD2+), and 92% of non-GAD2 neurons were NBCn1 positive (22 NBCn1+/24 GAD2− MAP2+). The scatter diagram in Fig. 10B shows that the overwhelming majority of cells are NBCn1-positive; these NBCn1-positive cells include all GAD2-positive neurons. However, not all GAD2-negatives are NBCn1 positive. Thus, the odds of a cell being NBCn1 negative are greater if it is GAD2 negative (8%, left side of plot) than in GAD2 positive (0%, right side of plot).

Fig. 10.

Summary of data on the co-labeling of nNCBTs and GAD2. The data summarized here come from many experiments like that in Fig. 9. (A) Summary of the total counts of cells in NBCn1 study. The legend beneath the bars indicates whether the cells were positive (+), negative (−), or either (blank cell) for MAP2, GAD2, and NBCn1. Thus, the left-most group of three bars indicates that we analyzed 40 MAP2+ cells, two of which were NBCn1−, and 38 of which were NBCn1+. (B) The scatter diagram describes the relationship between the intensities of the NBCn1 signal and GAD2 signal. (C) Summary of the total counts of cells in NDCBE study. (D) The scatter diagram describes the relationship between the intensities of the NDCBE signal and GAD2 signal. (E) Summary of the total counts of cells in NBCn2 study. (F) The scatter diagram describes the relationship between the intensities of the NBCn2 signal and GAD2 signal. Based on simple linear regression, the coefficient of determination R2 was <0.3 in panels B, D, and F.

NDCBE

In a different population of freshly dissociated cells, 85% were neurons (47 MAP2+/55 DAPI+), and 36% of these neurons were GABAergic (17 GAD2+/47 MAP2+; Table 2). The bar graphs in Fig. 10C show that 91% of neurons expressed NDCBE (43 NDCBE+/47 MAP2+), 63% of non-neurons expressed NDCBE (5 NDCBE+/8 MAP2−), 82% of GAD2 neurons were NDCBE positive (14 NDCBE+/17 GAD2+), and 96% of non-GAD2 neurons were NDCBE positive (29 NDCBE/30 GAD2− MAP2+). The scatter plot confirms that most GAD2-positive neurons express NDCBE (Fig. 10D). Viewed somewhat differently, the odds of a cell being NDCBE negative may be somewhat lower in GAD2-positive (18%, right side of plot) than in GAD2-negative (4%, left side of plot) neurons.

NBCn2

In the last population of freshly dissociated cells studied, 87% were neurons (41 MAP2+/47 DAPI+), and 37% of these neurons were GABAergic (15 GAD2+/41 MAP2+; Table 2). Fig. 10E shows that 98% of the neurons express NBCn2 (40 NBCn2+/41 MAP2+), 67% of non-neurons express NBCn2 (4 NBCn2+/6 MAP2−), 100% of GAD2 neurons were NBCn2 positive (15 NBCn2+/15 GAD2+), and 92% of non-GAD2 neurons were NBCn2 positive (24 NBCn2+/26 GAD2− MAP2+). The scatter plot indicates that all GAD2-positive neurons express NBCn2 (Fig. 10F). In addition, the odds of a cell being NBCn2 negative may be lower in GAD2-positive (0%, right side of plot) than in GAD2-negative (8%, left side of plot) neurons.

DISCUSSION

Strengths and limitations of experimental approach

Isolation of neurons

We elected to use freshly dissociated neurons rather than cultured neurons from the mouse MR. Advantages of acute dissociation include the ability to isolate relatively large numbers of cells from adult animals, and the likelihood that the proteins detected in the soma are more likely to reflect normal protein expression. Disadvantages are that the thick section of tissue could become somewhat hypoxic during the incubation periods (totaling 20 min in 100% O2 at room temperature), and that the trituration step of the procedure truncates neuronal appendages. To the extent that a particular nNCBT is degraded during the incubations, or is expressed in such appendages but not the soma, we would systematically undercount the nNBCT-positive neurons. Note that, our group has previously studied pHi regulation in freshly dissociated neurons using procedures similar to those of the present study (Bevensee et al., 1996; Chen et al., 2008b).

Determination thresholds

For each cell labeled with an antibody, we obtained a frequency distribution of pixel intensities for the fluorescent label. Accumulating the mean pixel intensity for each cell in the population of cells, we generated a range of means from least to greatest. As the threshold, we took the midpoint value between the highest mean value of negative-control cells and the lowest mean value of positive-observed cells. Although our method was simple and non-biased and appears to have been satisfactory, we could have used other statistical approaches for establishing a threshold for each antibody. For instance, instead of using the mean intensity from each cell, we could have used the median intensity or the peak intensity.

Another uncertainty is the validity of the negative control. In several cases we were able to exploit genetic tools. However, in the case of MAP2 and GAD2 experiments, we relied on incubating secondary antibodies without the primary antibodies as negative controls. Inspecting the data and the computed TPH thresholds in Fig. 8B, D, F, for example, might lead one to conclude that clear breaks in the TPH signals occurred just to the left of the thresholds, meaning that our approach may have yielded a few false negatives. A similar inspection of the GAD2 data and thresholds in Fig. 10 is consistent with the idea that our approach may have yielded one false positive in Fig. 10B. Thus, we conclude that our choice of algorithms for establishing thresholds is unlikely to have seriously affected the statistics presented below.

Limitation of antibodies for TPH and GAD

Our TPH antibody recognizes the gene products of both the Tph1 and Tph2 genes (Ni et al., 2008). On the other hand, our GAD2 antibody recognizes the GAD65 protein (encoded by the Gad2 gene) but not the GAD67 protein (encoded by the Gad1 gene). Gad2 and Gad1 genes are co-expressed in most GABAergic neurons, but the proteins that they encode are localized to different regions of the cell (Esclapez et al., 1994). GAD2 expression is higher in axon terminals (suggesting a role in GABA synaptic release), where GAD1 expression is lower. Conversely, GAD1 expression is higher in the cell body, where GAD2 expression is lower. Apropos of our discussion, the nucleus raphé magnus expresses the Gad2 gene (Zhang et al., 2011). Nevertheless, our approach of assaying the soma of freshly dissociated neurons for GAD2 may have led to a systematic underestimation of GABAergic neurons.

Limitation of antibodies for nNCBT variants

Our NBCn1 and NBCn2 antibodies should recognize all known variants of these proteins. However, our NDCBE antibody limited us to identifying only two out of the four known variants. Nevertheless, this antibody labeled 94% of all MAP2-positive cells. It is possible that some of the remaining 6% of MAP2-positive cells expressed one of the other two NDCBE variants. Clearly, it would be helpful to develop a common antibody that identifies all known variants of NDCBE.

Frequency distributions of serotonergic and GABAergic neurons in the MR

Table 3 summarizes the total count of serotonergic (TPH-positive) and GABAergic (GAD2-positive) neurons within the total neuronal population (MAP2-positive cells). Of the 295 freshly dissociated cells identified by DAPI, a total of 254 were positive for MAP2, 126 of which came from the TPH study, and 128 of which came from the GAD2 study. Thus, 86% of cells were neurons. Of the 126 MAP2-positive cells recorded in TPH experiments, 35 were TPH positive, meaning 28% of neurons in this sample were serotonergic. Also, of the 128 MAP2-positive cells analyzed from GAD2 experiments, 48 were GAD2 positive, meaning 38% of neurons in this sample were GABAergic.

Table 3.

Overall frequency distribution of neuronal populations

If the population of 128 neurons (from which we identified TPH- but not GAD2-positive neurons) is similar to the population of 126 neurons (from which we identified GAD2- but not TPH-positive neurons), then approximately half of the neurons came from populations that include chemosensitive neurons (Richerson, 2004). Indeed, of the 25 cells from ePet-EYFP mice summarized in Figs. 4 and 7 were EYFP positive (serotonergic) and five were GAD2 positive (GABAergic). Together, the two represent about half of all cells and more than half of all neurons.

Frequency distribution of nNCBTs in MR neurons

All neurons

We colocalized rabbit polyclonal antibodies directed against nNCBTs and mouse monoclonal antibody directed against MAP2. These data allowed us to determine the fraction of neurons and non-neuronal cells that expressed each transporter. Table 4 summarizes the total count of each nNCBT (NBCn1, NDCBE, and NBCn2) in MAP2-positive cells. Of the 82 MAP2-positive cells from the two NBCn1 studies (i.e., Figs. 8A and 10A), 79 were NBCn1-positive, meaning 96% of neurons contained the electroneutral Na+/ cotransporter-1.

Table 4.

Frequency distribution of nNCBTs among all neurons

Of the 90 MAP2-positive cells from the two NDCBE studies (i.e., Figs. 8C and 10C), 85 were NDCBE-positive, meaning that 94% of neurons contained the Na+-driven Cl–HCO3 exchanger.

Of the 82 MAP2-positve cells, 80 were NBCn2-positive from the two NBCn2 studies (i.e., Figs. 8E and 10E), meaning 98% of neurons contained the electroneutral Na+/ cotransporter-2.

In conclusion, we identified each of the three nNCBTs in a very large fraction of MR neurons (NBCn1: 96%, NDCBE: 94%, NBCn2: 98%). If expression of each transporter is independently associated, then 96% × 94% × 98% ≅ 88% of all MR neurons contain all three nNCBTs. Conversely, the odds of finding a neuron that does not express any of the three nNCBTs is only 4 × 6 × 2% ≅ 0.005%. In other words, virtually all MR neurons express significant levels of at least one of the NCBTs.

TPH-positive neurons

As discussed above (see Fig. 8), the frequency of nNCBTs among TPH-positive neurons is extremely high (93% NBCn1, 100% NDCBE, and 92% NBCn2), and is very similar to the nNCBTs frequency recorded from MR neurons in general (Table 5). These results conflict with our original hypothesis, which led us to predict that nNCBTs would be less abundant in chemosensitive serotonergic neurons than in non-serotonergic/non-GABAergic neurons, nearly all of which are not chemosensitive. However, we note that our antibody data do not address the issues of plasma-membrane expression or whether individual nNCBT molecules might be less active in the serotonergic neurons.

Table 5.

Frequency distribution of nNCBTs among TPH-positive and GAD2-positive neurons

Serotonergic neurons are extremely sensitive to CO2, increasing their firing rate in response to extracellular acidosis. A previous study has shown that the “electroneutral” Na+/ co-transporter NBCn1 has an intrinsic Na+ conductance (Choi et al., 2000).

The expression of nNCBTs has previously been linked to neuron excitability (Jacobs et al., 2008; Sinning et al., 2011), with a higher expression (presumably due to either higher steady-state pHi or a faster pHi recovery from an acid load) being correlated to an increase in excitability. Consistent with this notion, knocking out NDCBE (Sinning et al., 2011) or NBCn2 (Jacobs et al., 2008), both which would be expected to cause pHi to fall, is associated with a dramatic decrease in excitability and, in the case of the NDCBE KO, the release of glutamate in the hippocampus (Sinning et al., 2011). A paradox is that, in serotonergic MR neurons, respiratory acidosis, presumably by causing pHi to fall, triggers an increased firing rate (Wang et al., 2002). Perhaps NDCBE and the other nNCBTs prevent pHi from falling too far during respiratory acidosis, and thereby help to maintain a pHi permissive for a higher firing rate.

GAD2-positive neurons

We had hypothesized earlier that the nNCBTs would be less abundant in GABAergic neurons, many of which are chemosensitive, than in non-GABAergic/non-serotonergic MR neurons. On the contrary, our study shows that GAD2-positive neurons in the mouse MR have a high probability of expressing nNCBTs (100% NBCn1, 82% NDCBE, and 100% NBCn2; see Table 5).

A subpopulation of GABAergic MR neurons are extremely sensitive to CO2, undergoing a substantial decrease in firing rate in response to acid loads (Wang et al., 1998). The decrease firing in GABAergic neurons is believed to cause an increase in the respiratory drive because of decreased inhibition of inspiratory neurons. If the trigger for a decreased firing rate in GABAergic neurons is a fall in pHi, then one might speculate that a low nNCBT functional activity—the product of surface expression and the per-molecule activity of the transporters—could allow pHi to fall by an exaggerated amount in GABAergic neurons, helping to magnify the decrease in firing rate. As stated above, our present data do not address plasma-membrane expression levels or per-molecule activity of nNCBTs in the GABAergic neurons.

CONCLUSION

We unexpectedly found that nNCBT expression frequencies do not differ substantially among serotonergic vs. non-serotonergic, or among GABAergic vs. non-GABAergic. If chemosensitive neurons do indeed have different pHi physiologies compared to non-chemosensitive neurons, then it is possible that the plasma-membrane expression or the per-molecule activity of nNCBTs—rather than total protein levels per se—differs among different MR neuron subtypes. For example, different neuron subtypes could regulate permolecule activities of nNCBTs differently by using different alternative promoters, different combinations of splice cassettes, and different post-translational modifications (e.g., phosphorylation state). Another possibility is that acid–base transporters other than the nNCBTs (e.g., Na–H exchangers, Cl–HCO3 exchangers), or molecules such as carbonic anhydrases, are responsible for the hypothesized physiological differences in pHi homeostasis (Boron, 2004). Finally, it is possible that the pHi physiology of chemosensitive neurons is fundamentally similar to that of other neurons. In other words, the adequate stimulus to alter the firing rate of CO2-chemosensitive neurons might not be changes in pHi, but rather another parameter, such as pHo or [CO2]. In order to address these possibilities, one would need to measure—on the same neurons—some combination of firing rate, pHi homeostasis, and localization of acid–base transporters during the imposition of acid–base disturbances.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Evan Deneris for providing the ePet-EYFP mice (Neurosciences department, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland OH 44118), Dr. Christian Aalkjaer (Aarhus University, Denmark) for the NBCn1 (slc4a7) knockout mice, and Dr. Christian Hübner (Institute for Clinical Chemistry, University Hospital Jena, Friedrich Schiller Universität, Jena, Germany) for NDCBE (slc4a8) and NBCn2 (slc4a10) knockout mice. This work was supported by NIH Grant NS18400 (awarded to W.F.B.).

Abbreviations

- 5HT

5-hydroxytryptamine

- DIC

differential interference contrast

- GAD2

glutamic acid decarboxylase 2

- HBS

HEPES-buffered saline

- HEPES

hydroxyethyl piperazineethanesulfonic acid

- KO

knockout

- MAP2

microtubule associated protein-2

- NGS

normal goat serum

- Nt

amino-terminus

- PFA

paraformaldehyde

- pH0

extracellular pH

- pHi

intracellular pH

- MR

medullary raphé

- nNCBTs

electroneutral Na+-coupled transporters

- SLC4

solute-linked carrier 4

- TBS

Tris-buffered saline

- TBST

TBS with 0.05% Tween-20

- TPH

tryptophan hydroxylase

- WT

wild-type

REFERENCES

- Attaphitaya S, Park K, Melvin JE. Molecular cloning and functional expression of a rat Na+/H+ exchanger (NHE5) highly expressed in brain. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:4383–4388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.7.4383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevensee MO, Cummins TR, Haddad GG, Boron WF, Boyarsky G. PH regulation in single CA1 neurons acutely isolated from the hippocampi of immature and mature rats. J Physiol (Lond) 1996;494:315–328. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boedtkjer E, Praetorius J, Fuchtbauer EM, Aalkjaer C. Antibody-independent localization of the electroneutral Na+, -cotransporter NBCn1 (slc4a7) in mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;294:C591–603. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00281.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boron WF. Regulation of intracellular pH. Adv Physiol Educ. 2004;28:160–179. doi: 10.1152/advan.00045.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boron WF, Chen L, Parker MD. Modular structure of sodium-coupled bicarbonate transporters. J Exp Biol. 2009;212:1697–1706. doi: 10.1242/jeb.028563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley SR, Pieribone VA, Wang W, Severson CA, Jacobs RA, Richerson GB. Chemosensitive serotonergic neurons are closely associated with large medullary arteries. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:401–402. doi: 10.1038/nn848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Matsuyama K, Fujito Y, Aoki M. Involvement of medullary GABAergic and serotonergic raphe neurons in respiratory control: electrophysiological and immunohistochemical studies in rats. Neurosci Res. 2006;56:322–331. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LM, Choi I, Haddad GG, Boron WF. Chronic continuous hypoxia decreases the expression of SLC4A7 (NBCn1) and SLC4A10 (NCBE) in mouse brain. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293:R2412–R2420. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00497.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LM, Kelly ML, Parker MD, Bouyer P, Gill HS, Felie JM, Davis BA, Boron WF. Expression and localization of Na-driven Cl− exchanger (SLC4A8) in rodent CNS. Neuroscience. 2008a;153:162–174. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LM, Kelly ML, Rojas JD, Parker MD, Gill HS, Davis BA, Boron WF. Use of a new polyclonal antibody to study the distribution and glycosylation of the sodium-coupled bicarbonate transporter NCBE in rodent brain. Neuroscience. 2008b;151:374–385. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi I, Aalkjær C, Boulpaep EL, Boron WF. An electroneutral sodium/bicarbonate cotransporter NBCn1 and associated sodium channel. Nature. 2000;405:571–575. doi: 10.1038/35014615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connelly CA, Ellenberger HH, Feldman JL. Are there serotonergic projections from raphe and retrotrapezoid nuclei to the ventral respiratory group in the rat? Neurosci Lett. 1989;105:34–40. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran AE, Hodges MR, Wu Y, Wang W, Wylie CJ, Deneris ES, Richerson GB. Medullary serotonin neurons and central CO2 chemoreception. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2009;168:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esclapez M, Tillakaratne NJ, Kaufman DL, Tobin AJ, Houser CR. Comparative localization of two forms of glutamic acid decarboxylase and their mRNAs in rat brain supports the concept of functional differences between the forms. J Neurosci. 1994;14:1834–1855. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-03-01834.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes CJ, Mainville LS, Jones BE. Distribution of cholinergic, GABAergic and serotonergic neurons in the medial medullary reticular formation and their projections studied by cytotoxic lesions in the cat. Neuroscience. 1994;62:1155–1178. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90351-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung JP. The human raphe nuclei and the serotonergic system. J Chem Neuroanat. 2003;26:331–343. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs S, Ruusuvuori E, Sipila ST, Haapanen A, Damkier HH, Kurth I, Hentschke M, Schweizer M, Rudhard Y, Laatikainen LM, Tyynela J, Praetorius J, Voipio J, Hübner CA. Mice with targeted Slc4a10 gene disruption have small brain ventricles and show reduced neuronal excitability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:311–316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705487105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay AR, Wong RKS. Isolation of neurons suitable for patch-clamping from adult mammalian central nervous systems. J Neurosci Methods. 1986;16:227–238. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(86)90040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leviel F, Hübner CA, Houllier P, Morla L, El Moghrabi S, Brideau G, Hatim H, Parker MD, Kurth I, Kougioumtzes A, Sinning A, Pech V, Riemondy KA, Miller RL, Hummler E, Shull GE, Aronson PS, Doucet A, Wall SM, Chambrey R, Eladari D. The Na+-dependent chloride-bicarbonate exchanger SLC4A8 mediates an electroneutral Na+ reabsorption process in the renal cortical collecting ducts of mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1627–1635. doi: 10.1172/JCI40145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Xu K, Chen LM, Sun X, Parker MD, Kelly ML, LaManna JC, Boron WF. Distribution of NBCn2 (SLC4A10) splice variants in mouse brain. Neuroscience. 2010;169:951–964. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni W, Geddes TJ, Priestley JR, Szasz T, Kuhn DM, Watts SW. The existence of a local 5-hydroxytryptaminergic system in peripheral arteries. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:663–674. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker MD, Boron WF. The divergence, actions, roles, and relatives of sodium-coupled bicarbonate transporters. Physiol Rev. 2013 doi: 10.1152/physrev.00023.2012. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker MD, Musa-Aziz R, Rojas JD, Choi I, Daly CM, Boron WF. Characterization of human SLC4A10 as an electroneutral Na/HCO3 cotransporter (NBCn2) with Cl− self-exchange activity. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:12777–12788. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707829200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richerson GB. Serotonergic neurons as carbon dioxide sensors that maintain pH homeostasis. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:449–461. doi: 10.1038/nrn1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero MF, Fulton CM, Boron WF. The SLC4 family of transporters. Pflügers Arch. 2004;447:495–509. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1180-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott MM, Wylie CJ, Lerch JK, Murphy R, Lobur K, Herlitze S, Jiang W, Conlon RA, Strowbridge BW, Deneris ES. A genetic approach to access serotonin neurons for in vivo and in vitro studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16472–16477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504510102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinning A, Liebmann L, Kougioumtzes A, Westermann M, Bruehl C, Hübner CA. Synaptic glutamate release is modulated by the Na+ -driven Cl−/ exchanger Slc4a8. J Neurosci. 2011;31:7300–7311. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0269-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Pizzonia JH, Richerson GB. Chemosensitivity of rat medullary raphe neurones in primary tissue culture. J Physiol (Lond) 1998;511(2):433–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.433bh.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CZ, Yano H, Nagashima K, Seino S. The Na+-driven Cl−/ exchanger: cloning, tissue distribution, and functional characterization. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:35486–35490. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000456200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Bradley SR, Richerson GB. Quantification of the response of rat medullary raphe neurones to independent changes in pHo and PCO2. J Physiol (Lond) 2002;540:951–970. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Hodges MR, Richerson GB. Stimulation by hypercapnic acidosis in mouse 5-HT neurons in vitro is enhanced by age and increased temperature. 2008 Neuroscience Meeting; 2008. pp. 383–389. Planner Online. [Google Scholar]

- Xue J, Douglas RM, Zhou D, Lim JY, Boron WF, Haddad GG. Expression of Na+/H+ and -dependent transporters in Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 1 null mutant mouse brain. Neuroscience. 2003;122:37–46. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00598-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Cai YQ, Zou F, Bie B, Pan ZZ. Epigenetic suppression of GAD65 expression mediates persistent pain. Nat Med. 2011;17:1448–1455. doi: 10.1038/nm.2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]