Abstract

Objectives

To examine time-dependent changes of spirometry (percent-predicted FEV1[%FEV1])and the Pediatric Respiratory Assessment Measure (PRAM)during treatment of acute asthma exacerbations.

Study design

We conducted a prospective study of participants ages 5–17 years with acute asthma exacerbations managed in a Pediatric Emergency Department. %FEV1 and the PRAM were recorded pretreatment and at 2 and 4 hours. We examined responses at 2 and 4 hours following treatment and assessed whether changes of %FEV1 and of the PRAM differed during the first and second 2-hour treatment periods.

Results

Amongst 503 participants, median [IQR] age was 8.8 [6.9, 11.4], 61% were male and 63% African-American. There was significant mean change of %FEV1 during the first (+15.4%; 95%, CI 13.7, 17.1; P<0.0001) but not during the second 2 hour period (+1.5%; 95% CI −0.8, 3.8; P=0.21), and of the PRAM during the first (−2.1 points; 95% CI −2.3, −1.9; P < 0.0001) and second (−1.0 point; 95% CI −1.3, −0.7; P < 0.0001) 2 hour periods.

Conclusions

Most improvement of lung function and clinical severity occur in the first two hours of treatment. Amongst pediatric patients with acute asthma exacerbationsthe PRAM detects significant and clinically meaningful change of severity during the second 2-hours of treatment, whereas spirometry does not. This suggests that spirometry and clinical severity scores do not have similar trajectories and that clinical severity scores may be more sensitive to clinical change of acute asthma severity than spirometry.

Keywords: Asthma, spirometry, pulmonary function tests, pediatrics, PRAM score

INTRODUCTION

Asthma management guidelines recommend percent-predicted forced expiratory volume in 1-second (%FEV1) by spirometry or peak expiratory flow measurement to assess severity and response to treatment during acute exacerbations.(1;2)However, spirometry frequently is not available or cannot be obtained on pediatric patients during these episodes, and PEF may not accurately measure lung function during exacerbations.(3–5)Acute asthma severity scores can be obtained on all patients, including young children. Amongst proposed scores, the Pediatric Respiratory Assessment Measure (PRAM) has been validated for assessing acute asthma exacerbation severity.(6–8)For validation the PRAM developers used respiratory resistance measured by forced oscillation as the criterion standard. Further evidence that an acute severity score provides clinically meaningful information comparable to %FEV1 may be informative for both clinical care and expert asthma guideline development.

There is limited information on the changes of %FEV1 or the PRAM during treatment for acute asthma exacerbations in the emergency department.(9;10) Greater knowledge of these time-dependent changes might better inform decision making and improve resource utilization.

Our objective was to examine whether changes of %FEV1 and the PRAM during the first 2 hours of treatment differed from those during the second 2 hours of treatment in pediatric patients with acute asthma exacerbations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Participants

This study was undertaken as part of an ongoing, prospective investigation of participants with acute asthma exacerbations in an urban, academic children’s hospital emergency department (PED).(11)Between the hours of 7am and 10pm, we recruited patients ages 5 to 17 years who had doctor-diagnosed asthma and signs or symptoms of an asthma exacerbation,(12) were treated with systemic corticosteroid (CCS) and inhaled albuterol by the clinical team.

We excluded participants who had been treated with systemic CCS prior to presentation because of possible interference with the rate of change of %FEV1 and PRAM during the first 4 hours of treatment in the PED. We also excluded participants who were previously enrolledor who had clinical or radiographic evidence of pneumonia or other reason for pertinent signs and symptoms. Asthma assessment and treatment in our PED follows a collaborative protocol based on expert consensus guidelines.(1;13)The clinical team made all management decisions and was blind to the results of our testing. The Institutional Review Board approved the study (protocol #080058). Written informed consent was obtained from a parent or guardian of each participant and written assent or consent, as appropriate, from each participant. The principal investigator (DHA) had full access to all data for the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the analyses.

Measurements

A dedicated research assistant recruited and enrolled participants and was trained in spirometry performance and other study procedures.(11) Study data were acquired at three time points: pretreatment (before systemic CCS and albuterol treatment) and again at 2 and 4 hours after CCS administration if the participant remained in the PED at those times. All data were entered into a secure online database.(14)

The PRAM was developed by Chalut, Ducharme and colleagues and has face and criterion validity in pediatric patients with acute asthma exacerbations.(6;7) The PRAM is comprised of suprasternal and scalene muscle retractions, air entry, wheezing, and oxygen saturation with a score range of 0 to 12 points, 12 being the greatest severity (Table 1). Components of the PRAM were recorded separately, and scores were calculated electronically.

Table 1.

Pediatric Respiratory Assessment Measure (PRAM) severity score components and values assigned by severity of each component(1;2)

| Component values | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Signs | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Suprasternal retractions | No | Yes | ||

| Scalene contraction | No | Yes | ||

| Air entrya | Normal | Decreased at bases | Widespread decrease | Absent or minimal |

| Wheezinga | Absent | Expiratory only | Inspiratory and Expiratory | Audible without stethoscope or silent chest |

| O2 saturation | ≥ 95% | 92–94% | < 92% | |

Most severe side is used for rating if asymmetry is noted between right and left lung.

Reference List

Chalut DS, Ducharme FM, Davis GM. The Preschool Respiratory Assessment Measure (PRAM): a responsive index of acute asthma severity. J Pediatr. 2000 Dec;137(6):762-8.

Ducharme FM, Chalut D, Plotnick L, Savdie C, Kudirka D, Zhang X, Meng L, McGillivray D. The Pediatric Respiratory Assessment Measure: a valid clinical score for assessing acute asthma severity from toddlers to teenagers. J Pediatr. 2008 Apr;152(4):476-80, 480.

All participants present at each time point were asked to perform spirometry. We used a MicroDirect MicroLoop spirometer (Micro Medical, Kent, England),calibrated daily using a 3-liter syringe. A nose clip was applied, and we instructed each participant to perform FVC maneuvers in accordance with American Thoracic Society (ATS) and European Respiratory Society (ERS)spirometry standards.(15;16)

Some participants could not perform 3 FVC maneuvers at each time point that met full ATS criteria. Some of these trials included at least one FVC maneuver with volume-time and flow-volume curves meeting ATS criteria for start-of-test and end-of-test. A standing pulmonary function test oversight committee reviewed these trials and determined whether the data was of high quality and should be included for analysis.(11) The committee is comprised of a certified pediatric pulmonary function technician and a pulmonary physiologist. Each member recorded their determination of whether a non-ATS trial should be retained for analysis based on the volume-time and flow-volume curves and spirometry calculations of the available FVC maneuvers. Each member was blinded to the other’s determination and to all other participant data. A trial was included if both members determined independently that it was high quality.

The observational outcomes examined were time-based differences in the proportionate change of %FEV1 and of the absolute change of the PRAM from pretreatment to 2 hours (1st time period) and from 2 to 4 hours (2nd time period).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented as mean (SD) or median [IQR] as appropriate. Race and ethnicity were identified by the parent and categorized in accordance with NIH guidelines.(17) Some participants who could not perform pretreatment spirometry were able to do so at later time points, and some who were able to do so before treatment were not present at later time points. With these considerations in mind, %FEV1 values are presented for all studies available at each time point (all available data) as well as for those participants who provided studies at all three time points (complete data).

Using all available data, we performed a multivariable generalized least square regression analysis that accounted for the correlation of the repeated measures of %FEV1.(18)Models were adjusted for the a priori specified covariates age, gender, race, continuous albuterol treatment during each 2 hour treatment period, and pretreatment %FEV1 or PRAM as appropriate. Time dependent changes are reported using beta coefficients with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The β coefficient indicates absolute change where the null value is zero and is considered statistically significant when the corresponding 95% CI does not include zero. These effect sizes estimate the changes at 2hours from pretreatment and at 4 hours from 2 hours. These repeated measures regression analyses were also performed for absolute change of the PRAM during the two treatment periods. A two-sided significance level of 0.05 was used for all statistical inferences. Analyses were performed using R-software v. 2.12.1.(19)

RESULTS

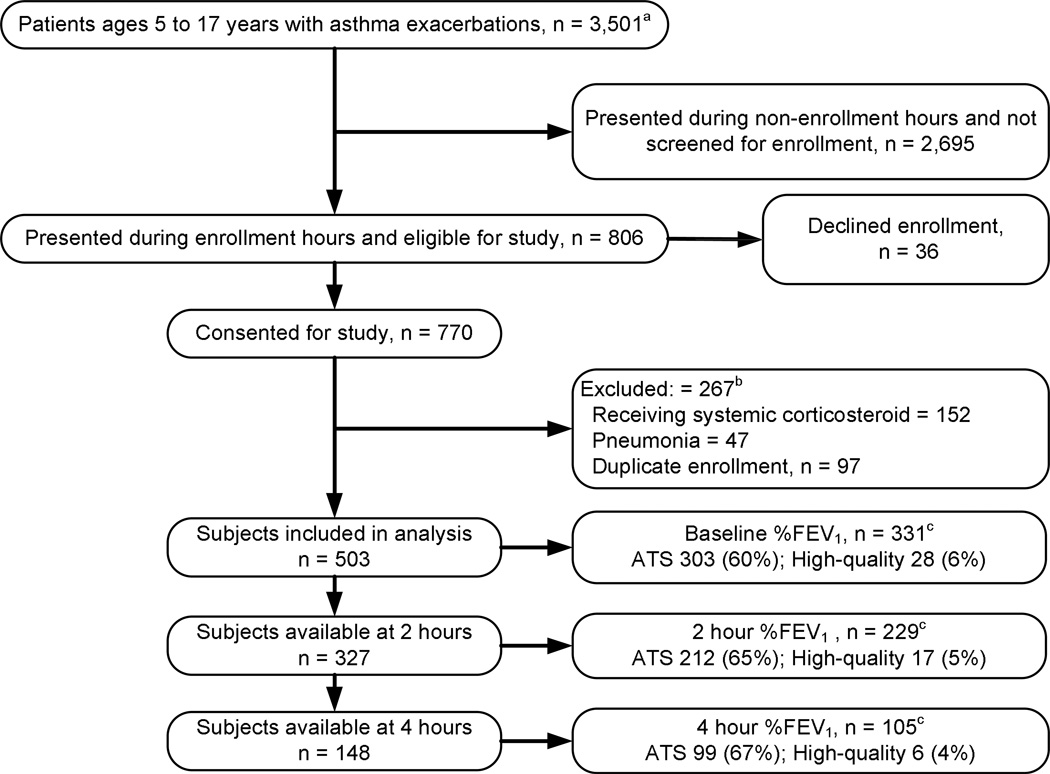

During the study period, April 8, 2008, to March 10, 2011, 806 patients who met inclusion criteria were approached for study participation, 770 were enrolled, 267 were excluded because of duplicate enrollment, prior treatment with systemic CCS, or pneumonia, and 503 are included for analyses (Figure 1). The demographic and asthma characteristics of participants are presented in Table 2.

Figure 1.

aOverall population of patients presenting to pediatric emergency department with final diagnosis of asthma exacerbation during study period

bNot mutually exclusive

cAble to perform spirometry meeting full ATS criteria or of high-quality as n (%) of participants available at time point

TABLE 2.

Demographic and Asthma Characteristics of Study Participants

| Characteristic | Study Sample (N = 503) |

|---|---|

| Demographic | |

| Age, years | 8.8 [6.9, 11.4] |

| Male | 306 (61) |

| Racea | |

| African-American | 315 (63) |

| White | 187 (37) |

| Hispanic ethnicitya | 37 (7) |

| Medicaid insurance | 319 (63) |

| Asthma | |

| Currently using inhaled CCS | 193 (38) |

| Prior PICU admission for asthma | 90 (18) |

| Prior ETI for asthma | 20 (4) |

| PED disposition | |

| Discharge to home | 429 (85) |

| Admit to floor bed | 55 (11) |

| Admit to PICU | 19 (4) |

Data are presented n (%) or median [IQR] where IQR = interquartile range.

CCS = corticosteroid; PICU = pediatric intensive care unit; ETI = endotracheal intubation

Race and Hispanic ethnicity are categorized in accordance with NIH guidelines and are not mutually exclusive.

Before treatment 303 (60%) participants performed full ATS criteria spirometry, and an additional 28 (6%) performed high quality studies. Full ATS or high quality studies were performed by 229 (70%) of those present at 2 hours and by 105 (71%) of those present at 4 hours (Tables 3 and 4). These tables include all available data as well as complete data, as defined in the Statistical Analysis section above.

TABLE 3.

FEV1 for participants ages 5 to 17 years with acute asthma exacerbations

| Absolute value, %FEV1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pretreatment | 2 hours | 4 hours | |

| All available dataa | 52 [36, 73] | 65 [47, 80] | 60 [44, 76] |

| Complete datab | 37 [26, 47] | 54 [42, 63] | 55 [43, 71] |

Values are median [IQR]

All valuesmeeting ATS or high quality spirometry criteria available at each time point (pretreatment, n = 331; 2hr, n = 229; 4hr, n = 105)

Values for only those participants who were available and able to provide ATS or high quality criteria spirometry pretreatment and at 2 and 4hr (n = 51)

TABLE 4.

Proportionate change of %FEV1 values for participants aged 5 to 17 years with acute asthma exacerbations

| Proportionate change, %FEV1 | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1st2 hours | 2nd 2 hours | |

| All available dataa | 29 [10, 65] | 4 [−3,14] |

| Complete datab | 34 [12, 72] | 5 [−6, 16] |

Values are median [IQR]

All values meeting ATS or high-quality spirometry criteria available at each time point (pretreatment and 2 hours, n = 199; 2 and 4 hours, n = 98)

Values for only those participants who were available and able to provide ATS or high quality criteria spirometry pretreatment and at 2 and 4hr (n = 51)

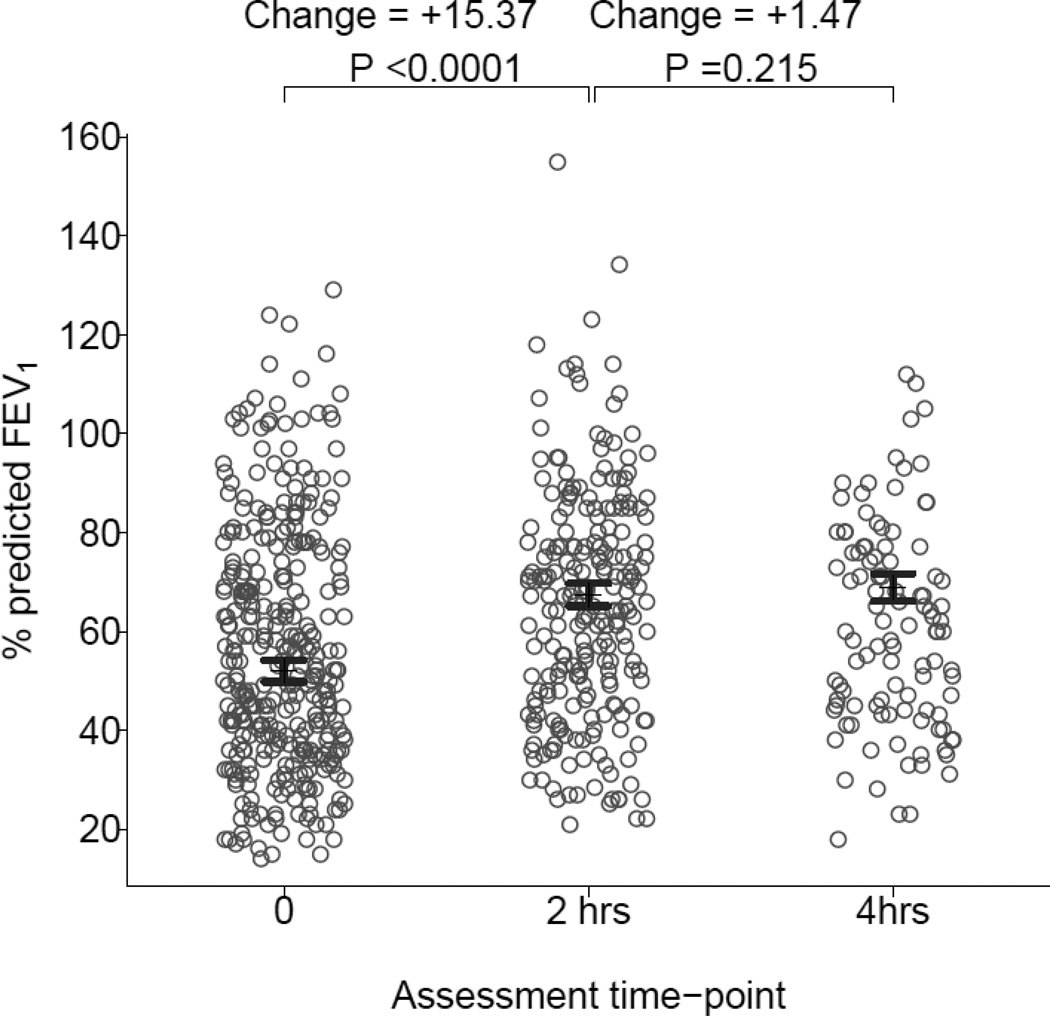

There was statistically and clinically significant improvement %FEV1 during the first 2 hour (adjusted mean difference: [+15.4%; 95%, CI 13.7, 17.1; P<0.0001]) but not during the second 2 hour period (+1.5%; 95% CI −0.8, 3.8; P=0.21) in the multivariable repeated measures analyses adjusted for age, gender, race, continuous albuterol treatment, and pretreatment %FEV1 (Figure 2). PRAM values are displayed in Table 5. There were statistically and clinically significant improvements in PRAM scores after the first (−2.1 points; 95% CI −2.3, −1.9; P < 0.0001) and second (−1.0 point; 95% CI −1.3, −0.7; P < 0.0001) 2 hour periods after adjustment for age, gender, race, continuous albuterol treatment, and pretreatment PRAM score.

Figure 2.

% FEV1 in participants available for testing who could perform spirometry before treatment (n = 331) and after 2-hours (n = 229) and 4-hours (n = 105) of treatment with continuous albuterol. Error-bars represent adjusted mean value bounded by 95% confidence intervals from multivariable model. Values for percent change of %FEV1 are at top.

TABLE 5.

Pediatric Respiratory Assessment Measure (PRAM) severity scorevalues for participants aged 5 to 17 years with acute asthma exacerbations

| Assessment time point during treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-treatmenta | 2 hrsb | 4 hrsc | |

| PRAM value | 3 [1, 5] | 1 [0, 4] | 1 [0, 2 |

| 1st 2 hoursb | 2nd 2 hoursd | ||

| Change of PRAM | −2 [−4, −1] | −1 [−3, 0] | |

Values are median [IQR]

Participants available for PRAM measurement at each time point or for each time interval: a503; b 327; c146; d146

DISCUSSION

The results of this study suggest that, amongst pediatric patients with acute asthma exacerbations, most clinically meaningful improvements of lung function measured using %FEV1 and a clinical severity score can be expected to occur in the first 2 hours of treatment. Specifically, we observed an overall 15.3% increase of %FEV1 during the first 2 hour treatment period and none during the second, and a 2 versus 1 point improvement of the PRAM. One might speculate that the mechanisms for this may include that activation of pulmonary β2-receptors is rapid and complete and that bronchodilation plateaus after the first 2 hours. As well, β2-receptor desensitization may have occurred in some participants during this period of sustained activation.(20;21) These findings are clinically relevant to practitioners in emergency departments and other acute care settings and may facilitate efficient and appropriate decision-making.

Moreover, improvement of the PRAM was noted after both the first and second 2-hour treatment periods. That continued improvement of this bedside severity score was detected, whereas that of %FEV1 was not, may have resulted from bias as a result of missing %FEV1 values, noted below.,

Although expert consensus guidelines continue to recommend %FEV1 measurement for acute asthma assessment, this measure is frequently not available in acute care settings and not possible in young children or those in respiratory distress. (1)) Langhan and Spiro obtained reproducible spirometry during exacerbations in 73% of 34 children with median age 12 years, and our participants achieved a rate of 60% (median age 8.8 years).(3) As such, a substantial proportion of patients are not able to perform spirometry during exacerbations.

We believe our findings also support the value of validated, effort-independent, bedside measures of acute asthma severity because these measures can be obtained in all patients and because they may better represent the clinically severity of children in respiratory distress than spirometry. There may also be clinical improvement that is not fully captured by spirometry. The PRAM is effort independent and can be obtained on all patients whereas spirometry requires considerable cooperation and coordination on the part of the patient. Although our findings indicate that a bedside acute severity score may be of greater use to clinicians in the emergency department, spirometry nonetheless provides an objective measure of lung function that is of great value in other clinical settings.

Limitations of our study include missing spirometry data that may introduce bias as some subjects were either unavailable because of disposition decisions or unable to perform spirometry at each time point. These participants may have had different asthma characteristics than those available or able to perform testing.(22) An additional limitation is the infrequency of PRAM scores over 8 in our cohort. This resulted from the infrequency of assigning 2-points for scalene muscle contractions or 3-points for completely absent breath sounds. This finding is at variance with that of Chalut, Ducharme and colleagues, who noted that all 5 components of the score contributed to the PRAM in their derivation and validation studies, although scalene muscle use was noted in only 2% of participants in the PRAM derivation study.(6;7) Notwithstanding the infrequency of scalene muscle use, significant and clinically meaningful change was noted for the PRAM during both the first and second 2-hour treatment periods.

In conclusion, our findings that most improvement of lung function and clinical severity occur in the first two hours of treatment suggests that disposition decisions for the pediatric patient with an acute asthma exacerbation can generally be made within 2 hours following initiation of systemic CCS and inhaled albuterol treatment. Equally important, this data suggests that spirometry and clinical measures of disease severity do not have similar change trajectories, and that clinical assessment tools may be more sensitive to change of severity. Although their improvement trajectories differ, spirometry and clinical measures of disease severity may both be important in assessing disease outcomes because they measure different physiological and clinical domains of acute exacerbation severity. This knowledge may improve resource utilization and decrease the burden of this illness on patients and families. In addition, expert management guidelines for acute asthma might consider the PRAM in place of FEV1 or PEFR testing for acute pediatric asthma assessment.

Acknowledgments

This work was performed at the Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN 37232.

Research support: This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health: [K23 HL80005] (Dr. Arnold); NIAID [K24 AI77930] (Dr. Hartert); and NIH/NCRR [UL1 RR024975] (Vanderbilt CTSA).

ABBREVIATIONS

- CCS

Corticosteroid

- %FEV1

Percent-predicted forced expiratory volume in 1-second

- PRAM

Pediatric Respiratory Assessment Measure

Footnotes

Author Disclosure Statements:

Data integrity: Dr. Arnold had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

COI: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Prior presentation: The results of this study were presented as a platform presentation, Pediatric Academic Societies, May, 2010, Vancouver, BC.

Contributor Information

Donald H Arnold, Email: don.arnold@vanderbilt.edu.

Tebeb Gebretsadik, Email: tebeb.gebretsadik@vanderbilt.edu.

Tina V Hartert, Email: tina.hartert@vanderibilt.edu.

Reference List

- 1.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. 2007 Available from http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/01_front.pdf.

- 2.O'Byrne PC. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention 7 A.D. Dec 10; doi: 10.1183/09031936.00138707. [cited 2008 Jan 28] Available from http://www.ginasthma.com/Guidelineitem.asp??l1=2&l2=1&intId=60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Langhan ML, Spiro DM. Portable spirometry during acute exacerbations of asthma in children. J Asthma. 2009 Mar;46(2):122–125. doi: 10.1080/02770900802460522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnold DH, Gebretsadik T, Abramo TJ, Hartert TV. Noninvasive testing of lung function and inflammation in pediatric patients with acute asthma exacerbations. J.Asthma. 2012 Feb;49(1):29–35. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2011.637599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eid N, Yandell B, Howell L, Eddy M, Sheikh S. Can peak expiratory flow predict airflow obstruction in children with asthma? Pediatrics. 2000 Feb;105(2):354–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.2.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chalut DS, Ducharme FM, Davis GM. The Preschool Respiratory Assessment Measure (PRAM): a responsive index of acute asthma severity. J Pediatr. 2000 Dec;137(6):762–768. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.110121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ducharme FM, Chalut D, Plotnick L, Savdie C, Kudirka D, Zhang X, Meng L, McGillivray D. The Pediatric Respiratory Assessment Measure: a valid clinical score for assessing acute asthma severity from toddlers to teenagers. J Pediatr. 2008 Apr;152(4):476–480. 480. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birken CS, Parkin PC, Macarthur C. Asthma severity scores for preschoolers displayed weaknesses in reliability, validity, and responsiveness. J Clin.Epidemiol. 2004 Nov;57(11):1177–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin RY, Pesola GR, Bakalchuk L, Heyl GT, Dow AM, Tenenbaum C, Curry A, Westfal RE. Rapid improvement of peak flow in asthmatic patients treated with parenteral methylprednisolone in the emergency department: A randomized controlled study. Ann Emerg Med. 1999 May;33(5):487–494. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(99)70334-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scarfone RJ, Fuchs SM, Nager AL, Shane SA. Controlled trial of oral prednisone in the emergency department treatment of children with acute asthma. Pediatrics. 1993 Oct;92(4):513–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arnold DH, Gebretsadik T, Abramo TJ, Sheller JR, Resha DJ, Hartert TV. The Acute Asthma Severity Assessment Protocol (AASAP) study: objectives and methods of a study to develop an acute asthma clinical prediction rule. Emerg Med J. 2011 May 17; doi: 10.1136/emj.2010.110957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanders DL, Gregg W, Aronsky D. Identifying asthma exacerbations in a pediatric emergency department: A feasibility study. Int.J Med Inform. 2006 Apr 27; doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dexheimer JW, Arnold DH, Abramo TJ, Aronsky D. Development of an asthma management system in a pediatric emergency department. AMIA.Annu.Symp.Proc. 2009 Nov 14;2009:142–146. 142–146. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2009 Apr;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Standardization of Spirometry, 1994 Update. American Thoracic Society. Am.J.Respir.Crit Care Med. 1995 Sep;152(3):1107–1136. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.3.7663792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, Crapo R, Enright P, van der Grinten CP, Gustafsson P, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur.Respir J. 2005 Aug;26(2):319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Institutes of Health. NIH policy on reporting race and ethnicity data: Subjects in clinical research. 2001 Aug 1; [cited 2008 Mar 8] Available from http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-01-053.html.

- 18.Pinheiro JC, Bates DM. Mixed-Effects Models in S and S-PLUS. 1st ed. New York: Springer Verlag; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 19.R Develpment core team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2011 Available from http://www.R-project.org.

- 20.Davis C, Conolly ME. Tachyphylaxis to beta-adrenoceptor agonists in human bronchial smooth muscle: studies in vitro. Br.J Clin.Pharmacol. 1980 Nov;10(5):417–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1980.tb01782.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hancox RJ, Aldridge RE, Cowan JO, Flannery EM, Herbison GP, McLachlan CR, Town GI, Taylor DR. Tolerance to beta-agonists during acute bronchoconstriction. Eur.Respir.J. 1999 Aug;14(2):283–287. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14b08.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donders AR, van der Heijden GJMG, Stijnen T, Moons KGM. Review: A gentle introduction to imputation of missing values. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2006 Oct;59(10):1087–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]