Abstract

Interleukin-10 is a pivotal determinant of virus clearance or persistence. Two human herpesviruses, Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) and human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) are unique among persistent viruses because they not only trigger production of host IL-10, but both viruses also encode homologs of IL-10 that are expressed during infection. Because anti-human IL-10 antibodies have diagnostic value and therapeutic potential for many chronic infections, cross-reactivity with ebvIL-10 and cmvIL-10 was evaluated in this study. Six of seven anti-hIL-10 antibodies tested recognized ebvIL-10 and neutralized its immuno-suppressive activity. In contrast, cmvIL-10 was neither recognized nor neutralized by any anti-human IL-10 antibody. These findings demonstrate that IL-10-neutralizing treatments in HCMV-or EBV-infected patients may require consideration of the contribution of viral IL-10 to disease pathology.

Keywords: Cytomegalovirus, Cytokines, Immune suppression, Antibodies

Persistent virus infections can cause devastating human diseases. Viruses that induce chronic infections employ a range of strategies for evading the host immune system, but one mechanism has emerged as a common theme: induction of IL-10 (Blackburn and Wherry, 2007; Kane and Golovkina, 2010). IL-10 is a pleiotropic cytokine that can effectively attenuate immune responses through the suppression of inflammatory cytokines and inhibition of T cell proliferation (Mosser and Zhang, 2008). Elevated levels of IL-10 have been noted in serum from patients infected with a number of persistent viruses, including HIV, hepatitis C virus, Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), and human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) (Budiani et al., 2002; Clerici et al., 1996; Nordoy et al., 2000; Reiser et al., 1997). In addition to causing elevation of host IL-10 levels, EBV and HCMV also encode viral homologs of IL-10 that are expressed during infection.

EBV and HCMV are members of the Herpesviridae family. These viruses each have a large, linear DNA genome surrounded by an icosahedral capsid, an amorphous tegument layer, and an envelope containing glycoprotein spikes. In addition to a common structure, herpesviruses have the ability to establish lifelong latency in the host. Successful coexistence with the host is mediated by numerous viral gene products that modify host immune responses and create a favorable environment for virus persistence. The specific immunomodulatory viral gene products vary among the herpesviruses, and EBV and HCMV are the only human herpesviruses that encode a viral homolog of IL-10. The BCRF1 gene of EBV is expressed during the lytic cycle; the 17kDa protein product shares 90% amino acid sequence identity with human IL-10 (hIL-10) and displays immune suppressive function (Hsu et al., 1990; Liu et al., 1997). The HCMV UL111A gene contains two introns and encodes a 17.6kDa protein with 27% amino acid sequence identity to hIL-10 that is expressed during productive infection (Kotenko et al., 2000; Lockridge et al., 2000). Despite low sequence conservation, cmvIL-10 forms biologically active dimers with structural similarity to hIL-10, binds with high affinity to the cellular IL-10 receptor, and exhibits potent immune suppressive activity (Jones et al., 2002; Spencer et al., 2002). Alternative splicing of the UL111A gene occurs during latency, and the resulting protein, LAcmvIL-10, exhibits only a subset of immunosuppressive functions (Jenkins et al., 2004, 2008).

Elevated serum IL-10 levels generally correlate with poor prognosis in patients with chronic infections and several types of cancer (Asadullah et al., 2003; Budiani et al., 2002; Ordemann et al., 2002). In murine models, persistent lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) infection was found to correlate with increased IL-10 production and impaired T cell responses (Brooks et al., 2006, 2008). Neutralizing IL-10 activity with antibodies resulted in rapid virus clearance, which was also observed when IL-10 knockout mice were infected with persistent LCMV strains. Induction of IL-10 was also documented in mice infected with murine cytomegalovirus (Redpath et al., 1999), and blocking the IL-10 receptor resulted in greatly reduced viral loads (Humphreys et al., 2007). While the use of IL-10-neutralizing antibodies for the treatment of human virus infection holds promise (Ejrnaes and von Herrath, 2007; Martinic and von Herrath, 2008), the existence of viral IL-10 homologs encoded by highly ubiquitous viruses like EBV and HCMV presents a serious complication in the development of treatments designed to counteract IL-10 activity.

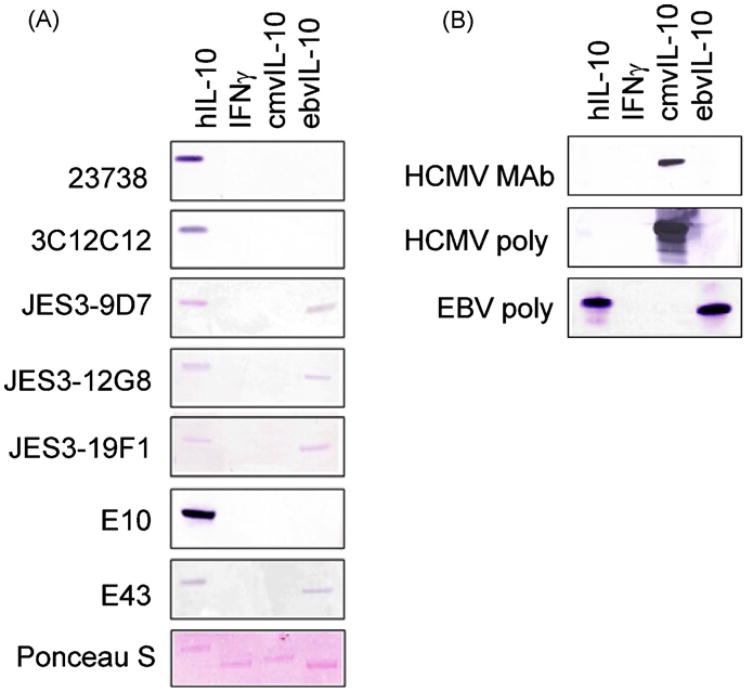

In order to examine whether hIL-10-specific antibodies recognize cmvIL-10 or ebvIL-10, Western blots were performed. Purified recombinant human and viral IL-10 proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. After blocking in PBS-Tween + 5% milk, the membranes were probed with the indicated anti-hIL-10 antibodies, followed by AP-conjugated secondary antibody. As shown in Fig. 1, all of the antibodies tested recognized hIL-10 in a Western blot. The intensity of bands varied significantly among these antibodies, with E10 consistently giving the darkest band and JES3-19F1 and JES3-12G8 showing fainter bands. All of the cytokines were present in equal amounts, as evidenced by Ponceau staining of the membranes prior to Western blotting. Interferongamma (IFNγ) served as a negative control cytokine and none of the antibodies showed any reaction with this protein.

Fig. 1.

Cross-reactivity of anti-hIL-10 antibodies by Western blot. Purified recombinant hIL-10, IFNγ, cmvIL-10, or ebvIL-10 (R&D Systems) were diluted to 10 μg/ml in PBS and analyzed by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a PVDF membrane, blocked, and then probed with the indicated antibodies at a dilution of 1:100 in PBS plus 5% milk. All anti-hIL-10 monoclonal antibodies are referred to by the clone name and were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. HCMV and EBV goat polyclonal antisera were obtained from R&D Systems and the HCMV monoclonal antibody was kindly provided by Dr. Gavin Wilkinson. Appropriate alkaline phosphatase conjugated secondary antibodies were used for detection at a dilution of 1:1000. Promega Western Blue Substrate was used for colorimetric detection of bands. Ponceau S staining was performed to confirm the presence of each cytokine on the membrane prior to Western blotting. Results are representative of three separate experiments.

Of the seven antibodies that recognized hIL-10, four of these (JES3-9D7, JES3-12G8, JES3-19F1, and E43) also detected ebvIL-10. This result is not surprising given the considerable sequence identity between hIL-10 and ebvIL-10. In contrast, cmvIL-10 has lower amino acid sequence identity with hIL-10 and was not recognized by any of the antibodies. Polyclonal antiserum directed against cmvIL-10 or ebvIL-10 was used as a control to confirm the identity of the viral cytokines. EbvIL-10 antiserum recognized both ebvIL-10 and hIL-10, while the cmvIL-10 antiserum was highly specific and did not cross-react with either hIL-10 or ebvIL-10. In addition, a monoclonal antibody raised against cmvIL-10 exhibited specificity for cmvIL-10 and failed to recognize either ebvIL-10 or hIL-10.

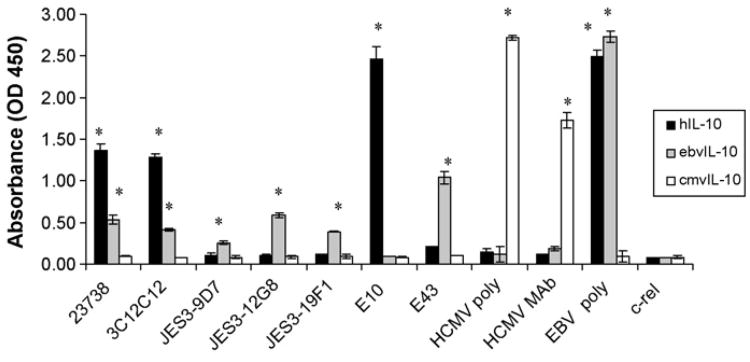

To evaluate antibody recognition of native protein and also allow for a relative measurement of affinity of the antibody for the target, ELISAs were performed. Purified recombinant human and viral IL-10 proteins were adsorbed to a microtiter plate for 15 h at 4 °C. The plate was washed, blocked with PBS containing 1% BSA, and then anti-hIL-10 antibodies were added at a concentration of 2 μg/ml. After incubation for 2h at room temperature, the plates were washed and antibody binding detected via the addition of HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. As shown in Fig. 2, three of the seven antibodies recognized hIL-10 in this assay. Antibody clones 23738, 3C12C12, and E10 all had absorbance values that were significantly higher than the background readings from the negative control c-rel antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Unexpectedly, four of the anti-hIL-10 antibodies that recognized hIL-10 by Western blot did not react with hIL-10 via ELISA (JES3-9D7, JES3-12G8, JES3-19F1, and E43). This suggests that either the epitopes for these antibodies may require protein denaturation or that adsorption to the ELISA dish obscured the epitope. Despite these possible limitations, all four of these antibodies recognized ebvIL-10 by both ELISA and Western blot. Again, none of the anti-hIL-10 antibodies recognized cmvIL-10, and the cmvIL-10 antibodies reacted with cmvIL-10 only.

Fig. 2.

ELISA detection by anti-human IL-10 antibodies. Purified hIL-10, cmvIL-10, or ebvIL-10 proteins were diluted to 2.5 μg/ml in PBS and used to coat a microtiter plate overnight at 4°C. After blocking, the indicated antibodies were added (4 μg/ml), followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:1000) and substrate reagent. An antibody to NF-κB family protein c-rel served as a negative control. Optical density was read at 450 nm following the addition of 1 M sulfuric acid stop solution to each well. Error bars represent standard error. Statistical analysis was performed using a two-tailed Student' t-test, and * indicates P< 0.01. Results are representative of four separate experiments.

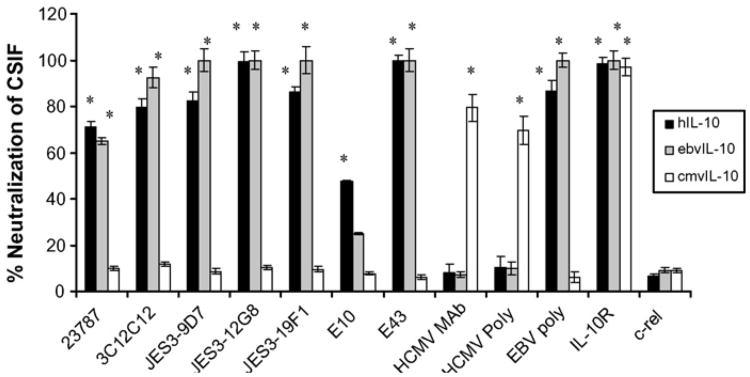

To further examine the specificity of these antibodies, a neutralization assay was performed. Suppression of inflammatory cytokines is a hallmark property of human and viral IL-10s (Moore et al., 2001; Slobedman et al., 2009), and hIL-10 was initially referred to as CSIF, or cytokine synthesis inhibitory factor (Fiorentino et al., 1989). The ability of each antibody to reduce IL-10-mediated cytokine suppression was evaluated. THP-1 monocytes were treated with 1 ng/ml lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to stimulate production of TNFα. In the presence of hIL-10, cmvIL-10, or ebvIL-10, TNFα production is greatly reduced, as described previously (Spencer, 2007; Spencer et al., 2002). Treatment with anti-hIL-10 antibodies neutralized CSIF activity and in several cases, fully restored TNFα levels (Fig. 3). An antibody to the human cellular IL-10 receptor (R&D Systems AF874) served as a positive control for neutralization and was effective at inhibiting cytokine suppression by hIL-10, cmvIL-10, and ebvIL-10. Six of the anti-hIL-10 antibodies almost completely neutralized both hIL-10 and ebvIL-10 CSIF activity, but no effect on cmvIL-10 function was observed with any anti-hIL-10 antibody. The ebvIL-10 antiserum was effective against both hIL-10 and ebvIL-10. Only the anti-cmvIL-10 antibodies neutralized cmvIL-10-mediated immune suppression, and these antibodies had no effect on the CSIF activity of either hIL-10 or ebvIL-10.

Fig. 3.

Effect of anti-human IL-10 antibodies onTNFα production. THP-1 monocytes were seeded into 96-well culture dishes at 2 × 104 cells per well and treated with 1 ng/ml LPS in the presence or absence of hIL-10, cmvIL-10, or ebvIL-10 (10ng/ml). After 24 h, supernatants were collected and TNFα levels determined by ELISA (R&D Systems) to determine total cytokine suppression for each cytokine. The indicated antibodies (5 μg/ml) were included just prior to the addition of human or viral IL-10 to neutralize CSIF activity. Results are expressed as percent neutralization, or the extent to which antibodies relieved TNFα suppression caused by the cytokines alone. Error bars represent standard error. Statistical analysis was performed using a two-tailed Student' t-test, and * indicates P<0.01. Results are representative of four separate experiments.

Antibody E10 exhibited the greatest specificity for hIL-10 but was unable to fully neutralize cytokine suppression, suggesting that the epitope for E10 may be distinct from the receptor contact sites. While E10 showed no recognition of ebvIL-10 via Western blot or ELISA, a modest decrease in CSIF activity was observed when this antibody was included in the reaction mix. EbvIL-10 has been shown to have greatly reduced affinity for the IL-10 receptor compared with hIL-10 (Liu et al., 1997), which may also account for the near complete neutralization of ebvIL-10 activity by antibodies that exhibited relatively weak recognition by Western blot or ELISA. The results for all of the commercially available antibodies tested are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Cross-reactivity of IL-10-specific antibodies.

| Clone | Isotype | Commercial source(s) | Reactivity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| hIL-10 | ebvIL-10 | cmvIL-10 | ||||

| 23738 | Mouse IgG2b | Abcam, Genway, Leinco Technologies, R&D Systems, Santa Cruz Biotech, Sigma–Aldrich | +a | +b | – | |

| 3C12C12 | Mouse IgG1 | CytoMol UniMed, LifeSpan Biosciences, Novus Biologicals, Santa Cruz Biotech | +a | +b | – | |

| JES3-9D7 | Rat IgG1 | Abcam, AbD Serotec, BD Pharmingen, Biolegend, Beckman Coulter, Biolegend, eBioscience, GeneTex, Inc., Genway, LifeSpan Biosciences, Novus Biologicals, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Southern Biotech, Thermo Scientific | +c | +a | – | |

| JES3-12G8 | Rat IgG2a | AbD Serotec, BD Pharmingen, Beckman Coulter, Biolegend, eBioscience, LifeSpan Biosciences, Novus Biologicals, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Southern Biotech, Thermo Scientific | +c | +a | – | |

| JES3-19F1 | Rat IgG2a | BD Pharmingen, Biolegend, Santa Cruz Biotechnology | +c | +a | – | |

| E10 | Mouse IgG2b | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | +d | – | – | |

| E43 | Mouse IgG2b | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | +c | +a | – | |

| EBV poly | Goat IgG polyclonal | R&D Systems (Catalog # AF915) | +a | +a | – | |

| HCMV poly | Goat IgG polyclonal | R&D Systems (Catalog # AF117) | – | – | +a | |

Western blot, ELISA, and neutralization.

ELISA and neutralization only.

Western blot and neutralization only.

Western blot and ELISA only.

IL-10 is an important regulator of anti-inflammatory activity in infection, autoimmune diseases, and cancer. The existence of viral IL-10s produced by herpesviruses that are widespread in the general population complicates both the measurement of IL-10 levels and therapeutic efforts to ameliorate IL-10 activity. Our results show that many anti-hIL-10 antibodies can recognize and neutralize both hIL-10 and ebvIL-10, but these antibodies do not detect cmvIL-10 or neutralize its biological activity. Due to the lack of recognition of cmvIL-10, LAcmvIL-10 was not tested for cross-reactivity with these anti-hIL-10 antibodies. LAcmvIL-10 is a truncated protein of 139 amino acids that is co-linear with cmvIL-10 for the first 127 amino acids (Jenkins et al., 2004). The C-terminal 12 amino acids of LAcmvIL-10 have no significant sequence similarity to either cmvIL-10 or hIL-10 (data not shown); thus, it is highly unlikely that hIL-10-specific antibodies that fail to recognize full length cmvIL-10 would detect LAcmvIL-10.

Detection of ebvIL-10 by some IL-10 reagents has previously been noted (Blay et al., 1993; de Waal Malefyt et al., 1991); however, this study represents the most comprehensive comparison of antibody cross-reactivity between hIL-10, ebvIL-10, and cmvIL-10. Although the antibodies tested here are marketed for research purposes, they could be produced for use as diagnostic tools or therapeutic treatments in the future. One antibody, JESG-12G8, has already been humanized and has potential for use as a clinical treatment (Presta, 2005). Given the success of other humanized monoclonal antibody therapeutics, anti-IL-10 antibodies could soon become important clinical tools, making it imperative that cross-reactivity with viral IL-10 homologs be thoroughly examined.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by University of San Francisco Faculty Development Funds (to J.V.S.). The authors thank Dr. Gavin Wilkinson for kindly providing the anti-cmvIL-10 monoclonal antibody. The anti-hIL-10 antibodies used in this study were all obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, but these antibodies are all available from multiple vendors and the authors thank technical service representatives from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, BDParmingen, and R&D Systems for many helpful discussions.

References

- Asadullah K, Sterry W, Volk HD. Interleukin-10 therapy–review of a new approach. Pharmacol Rev. 2003;55(2):241–269. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.2.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn SD, Wherry EJ. IL-10, T cell exhaustion and viral persistence. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15(4):143–146. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blay JY, Burdin N, Rousset F, Lenoir G, Biron P, Philip T, Banchereau J, Favrot MC. Serum interleukin-10 in non-Hodgkin' lymphoma: a prognostic factor. Blood. 1993;82(7):2169–2174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks DG, Lee AM, Elsaesser H, McGavern DB, Oldstone MB. IL-10 blockade facilitates DNA vaccine-induced T cell responses and enhances clearance of persistent virus infection. J Exp Med. 2008;205(3):533–541. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks DG, Trifilo MJ, Edelmann KH, Teyton L, McGavern DB, Oldstone MB. Interleukin-10 determines viral clearance or persistence in vivo. Nat Med. 2006;12(11):1301–1309. doi: 10.1038/nm1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budiani DR, Hutahaean S, Haryana SM, Soesatyo MH, Sosroseno W. Interleukin-10 levels in Epstein–Barr virus-associated nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2002;35(4):265–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerici M, Balotta C, Salvaggio A, Riva C, Trabattoni D, Papagno L, Berlusconi A, Rusconi S, Villa ML, Moroni M, Galli M. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) phenotype and interleukin-2/interleukin-10 ratio are associated markers of protection and progression in HIV infection. Blood. 1996;88(2):574–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Waal Malefyt R, Haanen J, Spits H, Roncarolo MG, te Velde A, Figdor C, Johnson K, Kastelein R, Yssel H, de Vries JE. Interleukin 10 (IL-10) and viral IL-10 strongly reduce antigen-specific human T cell proliferation by diminishing the antigen-presenting capacity of monocytes via downregulation of class II major histocompatibility complex expression. J Exp Med. 1991;174(4):915–924. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.4.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ejrnaes M, von Herrath MG. Cure of chronic viral infection by neutralizing antibody treatment. Autoimmun Rev. 2007;6(5):267–271. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentino DF, Bond MW, Mosmann TR. Two types of mouse T helper cell. J Exp Med. 1989;170(6):2081–2095. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.6.2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu DH, de Waal Malefyt R, Fiorentino DF, Dang MN, Vieira P, de Vries J, Spits H, Mosmann TR, Moore KW. Expression of interleukin-10 activity by Epstein–Barr virus protein BCRF1. Science. 1990;250(4982):830–832. doi: 10.1126/science.2173142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys IR, de Trez C, Kinkade A, Benedict CA, Croft M, Ware CF. Cytomegalovirus exploits IL-10-mediated immune regulation in the salivary glands. J Exp Med. 2007;204(5):1217–1225. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins C, Abendroth A, Slobedman B. A novel viral transcript with homology to human interleukin-10 is expressed during latent human cytomegalovirus infection. J Virol. 2004;78(3):1440–1447. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.3.1440-1447.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins C, Garcia W, Godwin MJ, Spencer JV, Stern JL, Abendroth A, Slobedman B. Immunomodulatory properties of a viral homolog of human interleukin-10 expressed by human cytomegalovirus during the latent phase of infection. J Virol. 2008;82(7):3736–3750. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02173-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BC, Logsdon NJ, Josephson K, Cook J, Barry PA, Walter MR. Crystal structure of human cytomegalovirus IL-10 bound to soluble human IL-10R1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(14):9404–9409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152147499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane M, Golovkina T. Common threads in persistent viral infections. J Virol. 2010;84(9):4116–4123. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01905-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotenko SV, Saccani S, Izotova LS, Mirochnitchenko OV, Pestka S. Human cytomegalovirus harbors its own unique IL-10 homolog (cmvIL-10) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(4):1695–1700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, de Waal Malefyt R, Briere F, Parham C, Bridon JM, Banchereau J, Moore KW, Xu J. The EBV IL-10 homologue is a selective agonist with impaired binding to the IL-10 receptor. J Immunol. 1997;158(2):604–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockridge KM, Zhou SS, Kravitz RH, Johnson JL, Sawai ET, Blewett EL, Barry PA. Primate cytomegaloviruses encode and express an IL-10-like protein. Virology. 2000;268(2):272–280. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinic MM, von Herrath MG. Novel strategies to eliminate persistent viral infections. Trends Immunol. 2008;29(3):116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KW, de Waal Malefyt R, Coffman RL, O'Garra A. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:683–765. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosser DM, Zhang X. Interleukin-10: new perspectives on an old cytokine. Immunol Rev. 2008;226:205–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00706.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordoy I, Muller F, Nordal KP, Rollag H, Lien E, Aukrust P, Froland SS. The role of the tumor necrosis factor system and interleukin-10 during cytomegalovirus infection in renal transplant recipien]ts. J Infect Dis. 2000;181(1):51–57. doi: 10.1086/315184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordemann J, Jacobi CA, Braumann C, Schwenk W, Volk HD, Muller JM. Immunomodulatory changes in patients with colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2002;17(1):37–41. doi: 10.1007/s003840100338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presta L. Interleukin-10 Antibodies. Schering Corporation, World Intellectional Property Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Redpath S, Angulo A, Gascoigne NR, Ghazal P. Murine cytomegalovirus infection down-regulates MHC class II expression on macrophages by induction of IL-10. J Immunol. 1999;162(11):6701–6707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiser M, Marousis CG, Nelson DR, Lauer G, Gonzalez-Peralta RP, Davis GL, Lau JY. Serum interleukin 4 and interleukin 10 levels in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol. 1997;26(3):471–478. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(97)80409-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slobedman B, Barry PA, Spencer JV, Avdic S, Abendroth A. Virus-encoded homologs of cellular interleukin-10 and their control of host immune function. J Virol. 2009;83(19):9618–9629. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01098-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer JV. The cytomegalovirus homolog of interleukin-10 requires phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity for inhibition of cytokine synthesis in monocytes. J Virol. 2007;81(4):2083–2086. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01655-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer JV, Lockridge KM, Barry PA, Lin G, Tsang M, Penfold ME, Schall TJ. Potent immunosuppressive activities of cytomegalovirus-encoded interleukin-10. J Virol. 2002;76(3):1285–1292. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.3.1285-1292.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]