Abstract

Oxidized phospholipids (OxPLs) are present on apolipoprotein (a) [apo(a)] and lipoprotein (a) [Lp(a)] but the determinants influencing their binding are not known. The presence of OxPLs on apo(a)/Lp(a) was evaluated in plasma from healthy humans, apes, monkeys, apo(a)/Lp(a) transgenic mice, lysine binding site (LBS) mutant apo(a)/Lp(a) mice with Asp55/57→Ala55/57 substitution of kringle (K)IV10)], and a variety of recombinant apo(a) [r-apo(a)] constructs. Using antibody E06, which binds the phosphocholine (PC) headgroup of OxPLs, Western and ELISA formats revealed that OxPLs were only present in apo(a) with an intact KIV10 LBS. Lipid extracts of purified human Lp(a) contained both E06- and nonE06-detectable OxPLs by tandem liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Trypsin digestion of 17K r-apo(a) showed PC-containing OxPLs covalently bound to apo(a) fragments by LC-MS/MS that could be saponified by ammonium hydroxide. Interestingly, PC-containing OxPLs were also present in 17K r-apo(a) with Asp57→Ala57 substitution in KIV10 that lacked E06 immunoreactivity. In conclusion, E06- and nonE06-detectable OxPLs are present in the lipid phase of Lp(a) and covalently bound to apo(a). E06 immunoreactivity, reflecting pro-inflammatory OxPLs accessible to the immune system, is strongly influenced by KIV10 LBS and is unique to human apo(a), which may explain Lp(a)’s pro-atherogenic potential.

Keywords: kringles, lipoproteins, plasminogen

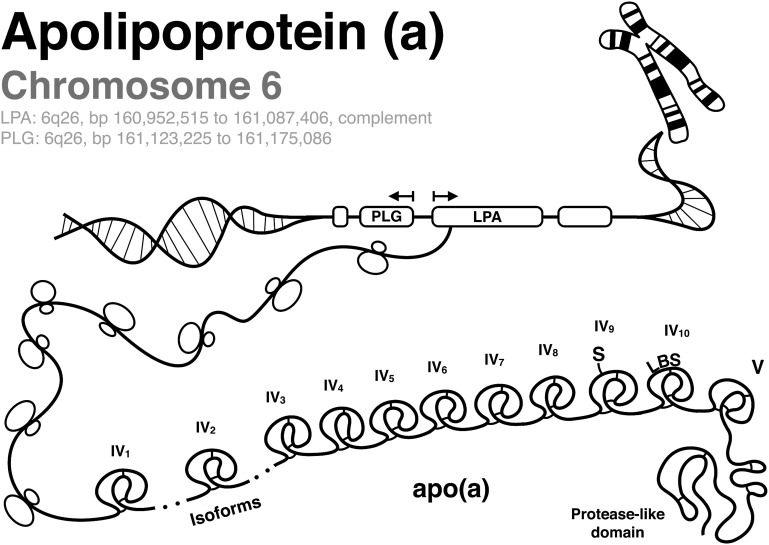

Lipoprotein (a) [Lp(a)] is composed of apolipoprotein (a) [apo(a)] covalently bound to apolipoprotein B-100 (apoB) via a single disulfide bond on kringle (K)IV type 9 (KIV9) to a site near the low density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor binding site of apoB (1–3). The LPA gene encoding apo(a) is present on chromosome 6q26 and is highly homologous to the plasminogen (PLG) gene (Fig. 1). PLG is a zymogen that is activated to plasmin and contains five Ks and a protease domain. Apo(a) contains only KIV and KV and has an inactive protease domain due to a Ser561-Ile562 substitution for Arg561-Val562 that prevents PLG activators from converting PLG to plasmin (4). In addition, apo(a) contains 10 subtypes of KIV; the KIV2 subtype is present in variable numbers of identically-repeated copies. Unlike the PLG gene that is present widely across species, the LPA gene appeared late during primate evolution and is present only in humans, nonhuman primates, and old world monkeys. An apo(a) variant exists in European hedgehogs, where it is present only as multiple copies of KIII and thus likely arose independently during evolution (5).

Fig. 1.

Genetic architecture of PLG and apo(a). The illustration depicts chromosome 6q26 containing the genes for PLG and apo(a) (LPA), which is transcribed into apo(a) containing KIV1, various repeats of KIV2, KIV3 to KIV8, KIV9 that contains an additional cysteine which covalently binds to apoB-100 of Lp(a) via a disulfide bond (S), KIV10 that contains the LBS, and the inactive protease domain.

Recent studies demonstrate that genetically elevated Lp(a) levels independently predict cardiovascular disease (CVD) and peripheral arterial disease (6–8). Mendelian randomization studies have also provided strong supporting evidence that Lp(a) is a genetic risk factor that may causally mediate CVD (9, 10). However, the underlying mechanisms by which Lp(a) mediates atherogenicity are not well understood (11).

We made the observation that Lp(a) is a preferential lipoprotein carrier of oxidized phospholipids (OxPLs) using a variety of experimental and clinical approaches (12–16). Furthermore, we developed an ELISA that quantitates phosphocholine (PC)-containing OxPLs on human apoB lipoproteins (OxPL/apoB), which primarily reflects the presence of OxPLs on the most atherogenic Lp(a) particles (17). OxPLs are highly prevalent in human vulnerable plaques (18) and in total chronic coronary occlusions (19). We have demonstrated that plasma OxPL/apoB levels identify angiographically-determined coronary artery disease (CAD) (14), predict the presence and progression of carotid and femoral atherosclerosis (20) and development of symptomatic peripheral arterial disease (21), and are elevated following acute coronary syndromes (12) and following percutaneous coronary intervention (22). Importantly, increased baseline levels of OxPL/apoB predict 15 year occurrence of new CVD events in previously healthy subjects independent of traditional risk factors and their Framingham risk score (6, 23), and allow reclassification of a significant number of subjects in intermediate Framingham risk category into higher or lower risk categories (24). Thus, OxPL/apoB appears to reflect the adverse consequences of highly atherogenic Lp(a) particles on CVD outcomes, but is also independently associated with CVD risk above and beyond Lp(a) levels in certain populations (6, 14). More recently, we also demonstrated that PLG of a variety of species contains covalently bound OxPLs (25). In contrast to the pro-atherogenic effects of OxPLs on Lp(a), OxPLs on PLG promote fibrinolysis, whereas the absence of OxPLs on PLG result in delayed fibrinolysis, which would be predicted to be atheroprotective (25).

In this study, we evaluate the potential determinants of OxPL binding on apo(a)/Lp(a) using several techniques, including isolated Lp(a) from humans, plasma from apes and monkeys, and recombinant apo(a) [r-apo(a)] constructs with a variety modifications encompassing apo(a) differences in various species. We also examine unique transgenic murine models expressing human Lp(a), including an apo(a) with mutations in a canonical lysine binding site (LBS) on KIV10, which is based on the sequences derived from KIV of PLG (26).

METHODS

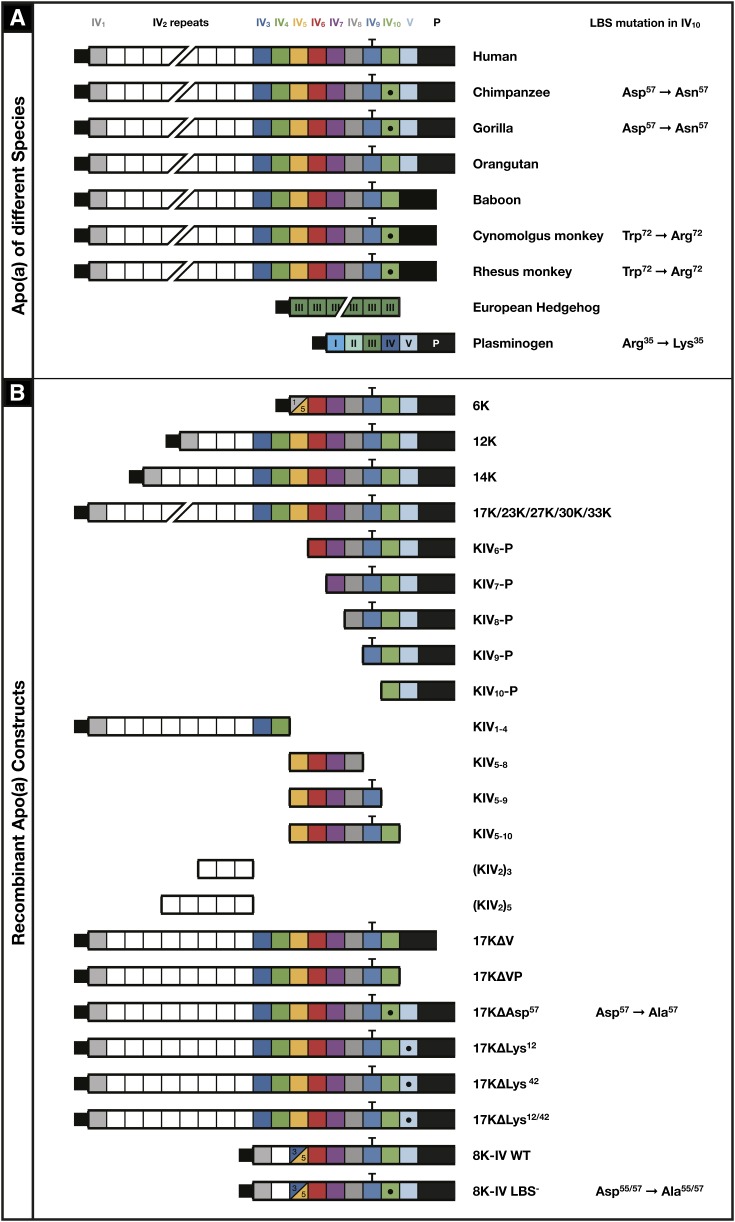

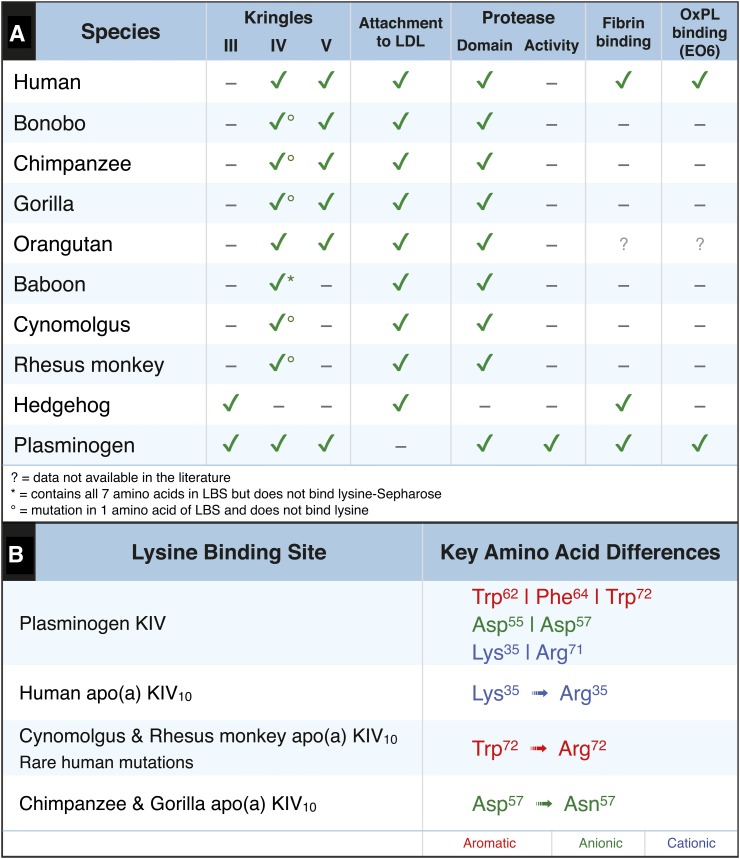

Composition of apo(a) of various species and of r-apo(a) constructs

Figure 2A displays the composition of apo(a) in various species used in this study. Compared with humans, all species except baboons and orangutans have differences in the seven amino acid LBS of KIV10. The r-apo(a) constructs studied contain a variety of modifications of Ks and KIV10 LBS, including the Asp57→Ala57 variant found in the chimpanzee and gorilla.

Fig. 2.

Description of the species differences in apo(a) at the various apo(a) Ks (A) and the various r-apo(a) peptides (B) used in this study. The domain structure of the full-length r-apo(a) construct comprising 17 kringles (17K) is presented at the top, where squares resemble individual Ks, subscripts 1 to 10 denote the subtypes of KIV sequences, KV denotes the KV-like sequence and P is the inactive protease domain. The T-bar over KIV9 indicates the location of the free-cysteine by which apo(a) is covalently bound to apoB-100 in Lp(a) via a disulfide bond. The dot within KIV10 indicates disruption of the LBS in this domain through mutagenesis and involved amino acids are indicated to the right. Variations include the 17K r-apo(a) without KV alone (17KΔV, baboon variant), also without the protease domain (17KΔVP), point mutations within the LBS (17KΔAsp57, chimpanzee and gorilla variants), or deletions of key amino acids of KV (17KΔLys12, 17KΔLys42, 17KΔLys12/42), as well as fragments of the 17K construct including KIV6-P, KIV7-P, KIV8-P, KIV9-P, KIV10-P, KIV6-P, KIV1–4, KIV5–8, KIV5–9, and KIV5–10, and longer (23K, 27K, 30K, 33K) and shorter versions (6K, 12K, 14K) with variations of the KIV2 repeats. 8K-IV indicates a short r-apo(a) version with a fusion of KIV3 to KIV5 that is identical to human apo(a) (WT) or has a disrupted LBS (LBS−).

Figure 2B displays the r-apo(a) variants representing naturally-occurring isoforms as well as various deletion and point mutants. These r-apo(a) constructs, which were derived from the original published human cDNA of apo(a), were generated from the expression plasmid pRK5 ha17 and their construction, expression, and purification have been previously described (27–30). Additionally, site-directed mutagenesis of pRK5 ha17 was used to generate new variants in which Lys12 or Lys42 in KV (17KΔLys12, 17KΔLys42) or both (17KΔLys12/42) were mutated to alanine with similar techniques as for the above r-apo(a) constructs. A construct comprised of the 8K-IV wild-type (WT) and 8K-IV lysine-binding defective mutant (LBS−) r-apo(a), used to generate transgenic mice with a truncated apo(a) as previously described (31–33), was also studied and their construction is described below.

Human subjects

All samples were acquired according to a study protocol approved by the University of California, San Diego Human Subjects Protection program and all study subjects gave their written informed consent before entering the study.

Source of animal plasma samples

Plasma samples from bonobos (Pan paniscus) (n = 4), chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) (n = 7), gorillas (Gorilla gorilla) (n = 6), and baboons (Papio species) (n = 3) were provided by the San Diego Wild Animal Park, and plasmas from cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) (n = 4) were obtained as previously described (34). WT C57BL/6×SJL, Apoe−/−, and Ldlr−/− mice were derived from existing mouse colonies. Apo(a) and Lp(a) transgenic mice with an apo(a) construct containing the apoE promoter and 8 KIV units (KIV1, a single copy of KIV2, a fusion of KIV3 and KIV5, and KIV6 to KIV10), KV, and the inactive protease-like domain on a C57BL/6×SJL background (n = 15) were previously described [termed 8K-IV apo(a)/Lp(a) mice] (33). These mice express both human apo(a) and human apoB-100 and have both elevated apo(a) and Lp(a) levels and increased levels of OxPLs on their apo(a)/Lp(a) particles (31–33). All animal studies were conducted using protocols approved by the University of Califormia, San Diego Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Generation of 8K-IV apo(a)/Lp(a) mice with defective KIV10 LBS

To generate 8K-IV apo(a)/Lp(a) mice with defective KIV10 LBS [8K-IV LBS− apo(a)/Lp(a) mice], the Asp55 and Asp57 residues in the KIV10 LBS apo(a) cDNA construct were replaced by Ala55 and Ala57 residues, as previously described (35). The vector, pRK5 ha8Lysmuta, was digested with BglII, polished with Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), and cut with EcoRI. The LBS mutant apo(a) fragment was inserted into a liver cDNA expression vector that had been digested with KpnI and polished and cut as described above. EcoRI sites were introduced into the 5′ and 3′ ends of the Apoe hepatic control region (LE6) by PCR with primers 5′-CGGGAATTCTGCAGGCTCAGAG-3′ and 5′-GGGAATTCGAGCTCCGCGGCAGCCTGACCA-3′ (the 3′ primer contained a nested SacII site). The LE6 was then ligated to the 3′ end of the LBS mutant apo(a) cDNA. The 8.6 kb LBS mutant apo(a) expression vector (containing the Apoe promoter, Apoe intron 1, the LBS mutant apo(a) cDNA, and LE6) was excised from pRK5 ha8Lysmuta with SacII, purified, and microinjected into C57BL/6×SJL zygotes. The resultant mice were designated LBS− apo(a) mice.

Breeding of 8K-IV WT and LBS− r-apo(a)/Lp(a) mice

Hemizygous LBS− apo(a) mice were crossed with hemizygous mice expressing human apoB-100 only, which were previously generated with an apoB mutation in codon 2,153 that prevented apoB-48 synthesis (36). All mice were on a C57/SJL background, weaned at 28 days of age, housed in a barrier facility with a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle, and fed a chow diet containing 4.5% fat (Ralston Purina, St. Louis, MO). Mice were genotyped by obtaining DNA from the tip of the tail and performing PCR using MyTaq HS Red Mix (BIOLINE, Inc., Taunton, MA). Forward and reverse primers for apo(a) were 5′-GACGGGAGACAGAGTGAAGC-3′ and 5′-TACCTAAACCACGCCAGGAC-3′, respectively, and for apoB 5′-GAAGAACTTCCGGAGAGTTGCAAT-3′ and 5′-CTCTTAGCCCCATTCAGCTCTGAC-3′, respectively. DNA samples were placed in a 1.5% agarose subgel containing ethidium bromide, run at 100 V for about 45 min, and visualized in a fluorescence reading chamber.

Expression of 8K-IV WT apo(a) and 8K-IV LBS− r-apo(a) constructs in mammalian cells

Recombinant WT 8K-IV apo(a) was expressed in human embryonic 293 kidney cells (HEK293) and purified with a lysine Sepharose column as previously described (32). The original 8K construct in the pRK5 ha vector contained no selection gene. To introduce the 8K-IV LBS− r-apo(a) cDNA into HEK293 cells, a cotransfection assay was performed using pcDNA3 containing a G418 Lipofectamine transfection reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) using a 3:1 ratio in order to ensure that the gene of interest was expressed. After several rounds of selection, individual colonies were selected and grown. Each colony was tested for expression by concentrating the media with 10,000 NMWL Amicon Ultra Centrifugal Filter Units from Millipore (Billerica, MA), purifying the 8K-IV LBS− r-apo(a) by size exclusion chromatography (SW400 resin), and analyzing by both ELISA and Western blot. Nontransfected cells were also analyzed as a negative control.

Antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies MB47 specific for human apo B-100, LPA4 specific for apo(a), and E06 specific for the PC headgroup of OxPLs were previously described in detail (22).

Tandem LC-MS/MS analysis of OxPLs on r-apo(a) constructs

LC-MS/MS was utilized to assess the covalent binding of PC-containing OxPLs on the WT 17K r-apo(a) as well as the r-apo(a) 17KΔAsp57, which has a substitution of Asp57 to Ala57 in the LBS of KIV10. The 17K and 17KΔAsp57 r-apo(a) were thermally denatured, the disulfide bonds reduced by dithiothreitol (DTT), alkylated by iodoacetamide, and then digested with trypsin. In brief, to 100 μl of r-apo(a) (1 μg/μl in deionized water) was added 100 μl of ammonium bicarbonate buffer (50 mM pH 8) and 2 μl of 1 M DTT. The mixture was incubated at 50°C for 15 min. Twenty-five microliters of a saturated solution of iodoacetamide in DI water was added to the reaction mixture, which was kept in the dark at room temperature for 15 min. One half of the reaction mixture was then hydrolyzed in 30% NH4OH for 14 h and the reaction mixture subjected to vacuum overnight to remove NH4OH. The residue was reconstituted in 100 μl ammonium bicarbonate buffer and digested in trypsin with a molar ratio of 50:1 (r-apo(a):trypsin) overnight. The digested peptides were purified by solid phase extraction. A Waters SepPak Vac C18 1 cc cartridge was preconditioned with 1 ml of CH3CN and 1 ml water; the digested peptides were loaded on the cartridge and washed with 1 ml of DI water. The peptides were eluted with 1 ml CH3CN. The solvent was evaporated and the residue reconstituted in 100 μl of DI water.

LC-MS/MS analysis was carried out on a triple quadrupole instrument Thermal TSQ Vantage mass spectrometer coupled with a Waters NanoAcquity autosampler/UPLC system, as previously described (25, 37). The LC separation was achieved on a trapping column with 5 cm of 5 μm Jupiter C18 reverse phase material pressure-packed into a fused silica capillary (360 μm o.d. × 100 μm i.d.) and a resolving (analytical) column with 18 cm of 3 μm Jupiter C18 material pressure-packed into a capillary (360 μm o.d. × 100 μm i.d.) with a laser-pulled tip for nano-electrospray ionization. Full scan monitoring was carried out to scan a mass range of m/z 350 to 1,500. Precursor ion scanning (PIS) monitoring was carried out to identify a product ion of m/z 184, which is characteristic for the PC headgroup.

Identification of OxPLs in r-apo(a) constructs and plasma of humans and animals by chemiluminescent ELISA

The presence of apo(a), Lp(a), apoB, OxPL/apo(a), and OxPL/apoB in the various purified recombinant proteins and mouse, animal, and human plasma was performed by a variety of immunoassays, as previously described (17, 31, 32). Values are reported as relative light units (RLU) per 100 ms using chemiluminescent ELISA. Both direct plating of material and double antibody sandwich assays were utilized. Briefly, for direct plating assays, r-apo(a) constructs (5 μg/ml) or plasma (1:100 dilution) were plated on microtiter well plates overnight and apo(a) detected with antibody LPA4, OxPLs with antibody E06, and human apoB detected with antibody MB47, which does not cross-react with mouse apoB. For OxPL/apo(a) sandwich ELISA, LPA4 (5 μg/ml) as capture antibody was plated overnight and constructs (5 μg/ml) or plasma (1:100 to 1:400 dilution) added and OxPLs detected with biotinylated E06 (2 μg/ml). The human, ape, and monkey plasma samples were usually used at a 1:400 dilution, which was established as the concentration at which the relationship is linear. For OxPL/apoB sandwich ELISA, MB47 (5 μg/ml) as capture antibody was plated overnight and constructs (5 μg/ml) or plasma (1:100 dilution) added and OxPLs detected with biotinylated E06 (2 μg/ml). To determine Lp(a) levels in transgenic 8K-IV Lp(a) and 8K-IV LBS− Lp(a) mice, MB47 was immobilized on microtiter well plates for capture of human apoB, plasma added (1:400), and Lp(a) detected with antibody LPA4. To determine apo(a) levels in 8K-IV WT and 8K-IV LBS− r-apo(a) constructs, apo(a) was captured on microtiter well plates with LPA4 (5 μg/ml), constructs (5 μg/ml), and apo(a) detected with antibody LPA4 (the TRNYCRNPDAEIRP epitope for LPA4 is present on KIV-5, KIV-7, and KIV-8).

Identification of OxPLs in human Lp(a) by LC-MS/MS

Lp(a) from subjects with hypercholesterolemia was isolated using density gradient ultracentrifugation followed by size exclusion chromatography with a Sephacryl S-400 or lysine Sepharose chromatography (16). We extracted the OxPLs from intact purified Lp(a) with 2:1 chloroform:methanol and analyzed the extract for the presence of 1-palmitoyl-2-(5-oxovaleroyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POVPC) (38–40), 1-palmitoyl-2-glutaroyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (PGPC), and epoxy-isoprostane-phosphocholine (PEIPC), which are highly bioactive OxPLs (41, 42). To identify specific species of OxPLs in the lipid phase of Lp(a) (i.e., extractable OxPLs), we employed reversed phase liquid chromatography directly coupled to a triple quadrupole MS (LC-MS/MS), as recently described (40, 43, 44). In brief, for PC, lyso-PC, and oxidized PC containing OxPLs (PC-OxPL) analysis, protonated adducts (PC + H)+, (lyso-PC + H)+, and (PC-OxPL + H)+ are formed when operating the ion source in positive electrospray mode. The MS is operated in PIS mode using a collision energy setting of 35 V and a mass scan range of 500 to 900 atomic mass units. In a specified PIS mode, the MS detects all precursor ions within the mass scan range that produce the specified fragment. PC and lyso-PC species produce the PC headgroup with m/z = 184, regardless of their parent mass or moiety. Applied Biosystems MS software (Analyst 1.5.1) using the extracted ion current (XIC) option allows a search for specified precursor masses detected during the run.

Immunoblot analyses

Nonreducing SDS-PAGE of various apo(a) constructs, purified Lp(a), and PLG (all at 1 μg/ml) was carried out using precast gradient gels with 4–12% polyacrylamide concentrations and performed on a Xcell SureLock Mini-Cell system (Invitrogen) for 1.5 h in 1× MOPS SDS (NuPAGE MES SDS Running Buffer). The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline and Tween for 1 h. Incubation with biotinylated LPA4 and biotinylated EO6 was performed on separate membranes in 1% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline and Tween overnight at 4°C. Protein detection was performed with streptavidin conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) from R and D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). For visualization Supersignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Rockford, IL) was used as substrate and fluorescence detected at 428 nm wavelength on a BioSpectrumAC imaging system using VisionWorksLS imaging acquisition and analysis software from UVP (Upland, CA). In these immunoblots, OxPLs are denoted to reflect only E06-detectable OxPLs and not all OxPLs.

Statistics

For grouped numerical values, a mean value ± standard deviation (mean ± SD) was calculated. Analysis of quantitative parameters between groups was performed by two-tailed Student's unpaired t-test and within the same group by paired t-test or with repeated-measures one-way ANOVA. P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. Data presented in the text and tables are mean ± SD and in figures mean value ± standard error of the mean (mean ± SEM).

RESULTS

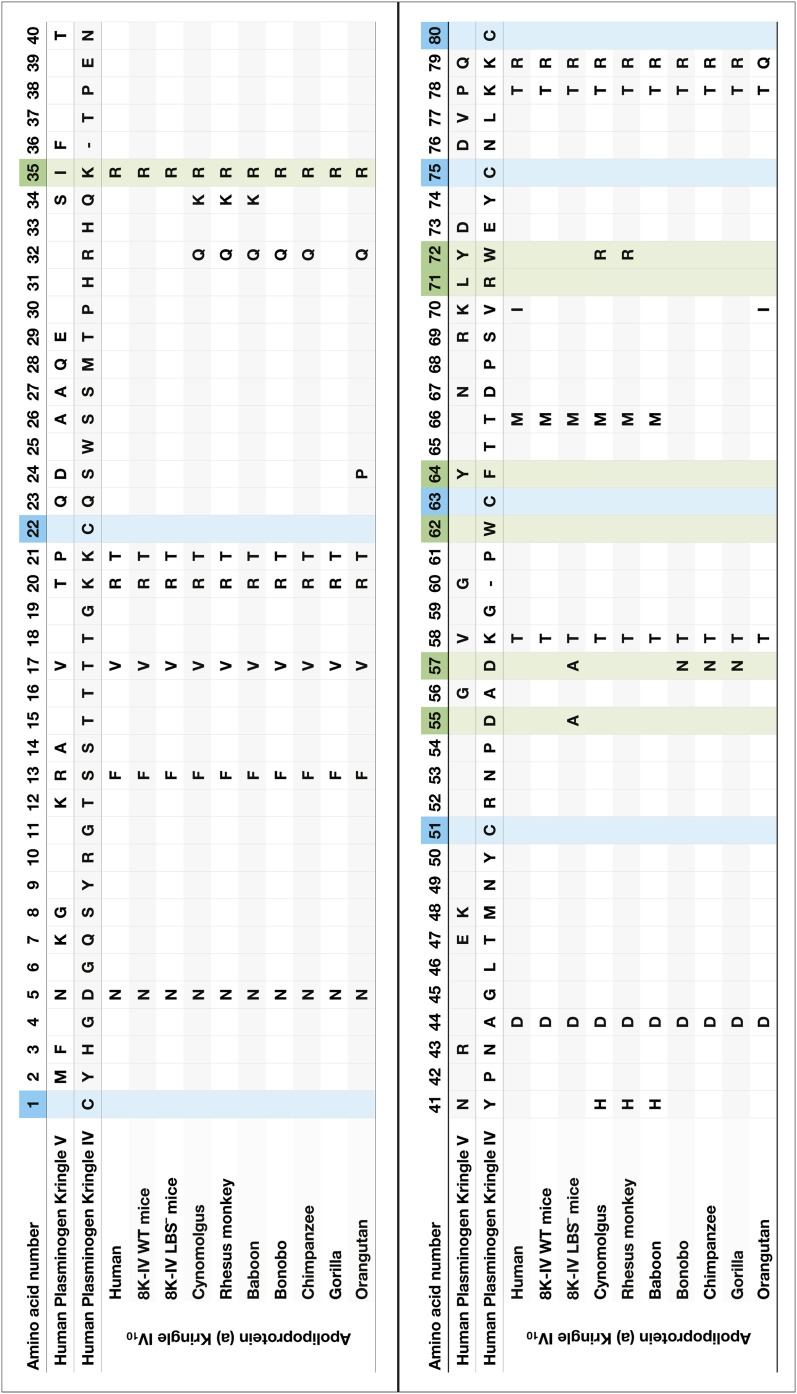

The LBS of KIV10 apo(a) consists of seven amino acids as follows by convention using the nomenclature of KV of PLG: Arg35, Asp55, Asp57, Trp62, Phe64, Arg71, and Trp72. Because of the presence of several naming systems in the literature and differences in the number of amino acids in Ks between species, we provide a comparative summary of PLG KIV and KV, and apo(a) KIV10 of various species in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Amino acid composition of human PLG KIV and KV10 and human, ape, and monkey apo(a) KIV10. One-letter symbols indicate amino acid changes and empty fields identical amino acids compared with KIV of human PLG. Blue: cysteine forming the disulfide bonds in the K structure. Green: amino acids of the LBS. Numbering according to KV of PLG. Note: KIV of PLG and IV10 subtypes of apo(a) are missing two amino acids compared with KV (indicated by a minus sign).

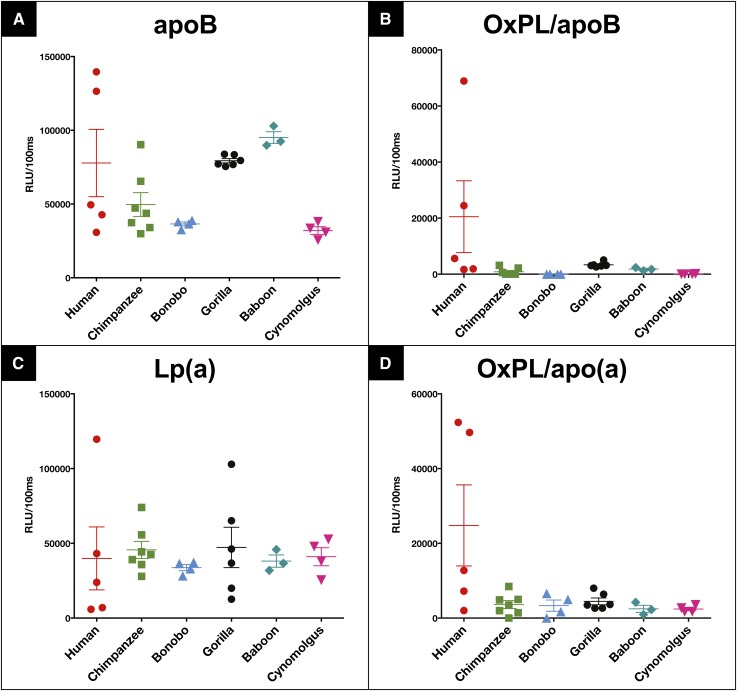

Determination of OxPLs on Lp(a) and apoB from humans, apes, and monkeys using ELISA techniques

OxPL/apoB and OxPL/apo(a) were measured in five humans with widely different Lp(a) levels (data from >15,000 analyses of human plasma for OxPL/apoB and Lp(a) have been published previously (17), therefore we only show data from five representative humans for comparison), chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, baboons, and cynomolgus monkeys, and presented as mean levels and individual data points. Figure 4A, C demonstrates the levels of apoB and Lp(a) captured on the plates from each of the different samples. Figure 4B, D demonstrates the levels of OxPLs on apoB-100 particles and on apo(a) for each of these samples. It can be appreciated that OxPL/apoB and OxPL/apo(a) are mainly present in the humans with high Lp(a) levels, as previously well documented (17). However, all other species had essentially undetectable OxPL/apoB and OxPL/apo(a) levels, with values at or below the sensitivity of these assays (Fig. 4B, D). Importantly, E06 immunoreactivity was not present in chimpanzees and gorillas whose Lp(a) is known to contain KV.

Fig. 4.

ApoB-100 (A), OxPL/apoB (B), Lp(a) (C), and OxPL/apo(a) (D) of human (n = 5), chimpanzee (n = 7), bonobo (n = 4), gorilla (n = 6), baboon (n = 3), and cynomolgus monkey (n = 4) plasma. Bars indicate mean value and standard error of the mean. RLU, relative light units.

Determination of OxPLs on 8K-IV WT apo(a) and 8K-IV LBS− apo(a) recombinant constructs

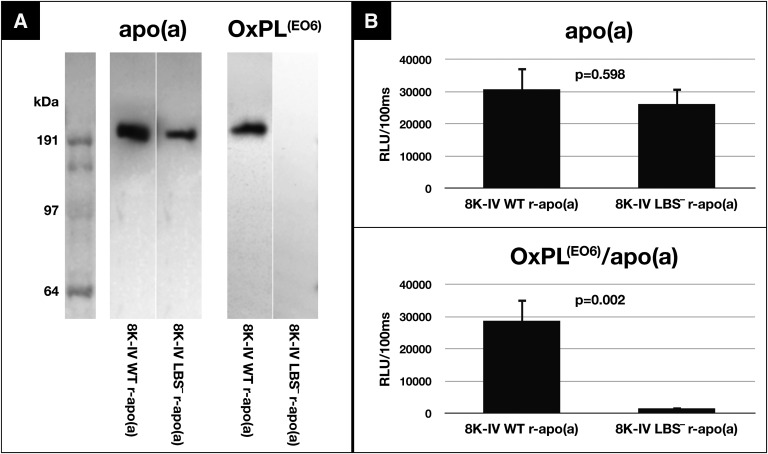

Immunoblot analysis of supernatants of HEK293 cells expressing 8K-IV WT r-apo(a) and 8K-IV LBS− r-apo(a) constructs demonstrates apo(a) immunoreactivity, detected by antibody LPA4, as expected (Fig. 5A). However, OxPLs detected by antibody EO6 is only present in the 8K-IV WT r-apo(a) but not in the LBS− r-apo(a) construct. There are no other E06 positive bands throughout the gel, suggesting that there are no other expressed proteins containing significant OxPLs. ELISA shows similar apo(a) levels for both variants, but OxPLs are only present in the WT 8K-IV r-apo(a) and not the LBS− 8K-IV r-apo(a) construct (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

WT versus LBS-deficient 8K-IV r-apo(a) from HEK293 cell line. A: Western blot: LPA4 detects both the WT and mutant r-apo(a), which were loaded after purification by lysine-Sepharose binding and by size exclusion chromatography. Only the WT r-apo(a) has EO6 reactivity, unlike the LBS-deficient r-apo(a) construct. B: ELISA: both versions of the r-apo(a) are detectable with LPA4, however only the WT version shows EO6 reactivity. RLU, relative light units.

Determination of the presence of OxPLs on 8K-IV WT Lp(a) and 8K-IV LBS− Lp(a) transgenic mice

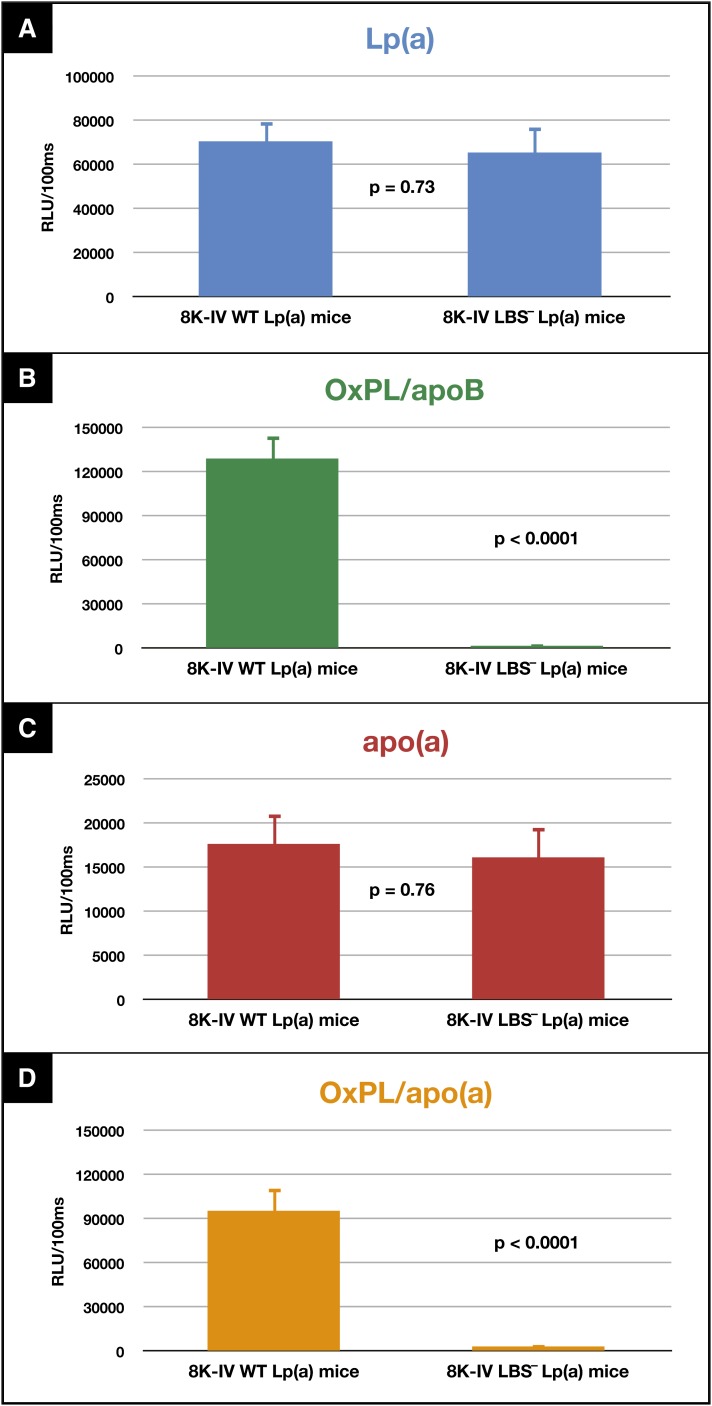

Circulating Lp(a) and apo(a) levels were not statistically different between 8K-IV WT Lp(a) and 8K-IV LBS− Lp(a) mice (Fig. 6A, C). However, OxPL/apoB (Fig. 6B, P < 0.0001) and OxPL/apo(a) (Fig. 6D, P < 0.0001) levels were significantly higher in the 8K-IV WT Lp(a) mice compared with the 8K-IV LBS− Lp(a) mice, where levels were essentially nondetectable.

Fig. 6.

Lp(a) (A), OxPL/apoB (B), apo(a) (C), and OxPL/apo(a) (D) measurements of plasma from WT Lp(a) transgenic mice and LBS-deficient Lp(a) transgenic mice. Plasma from each of these mice was subjected to the various assays described in Methods, and the results presented as relative light units (RLU)/100 ms. Plasma from 15 WT and 15 LBS-deficient mice were studied.

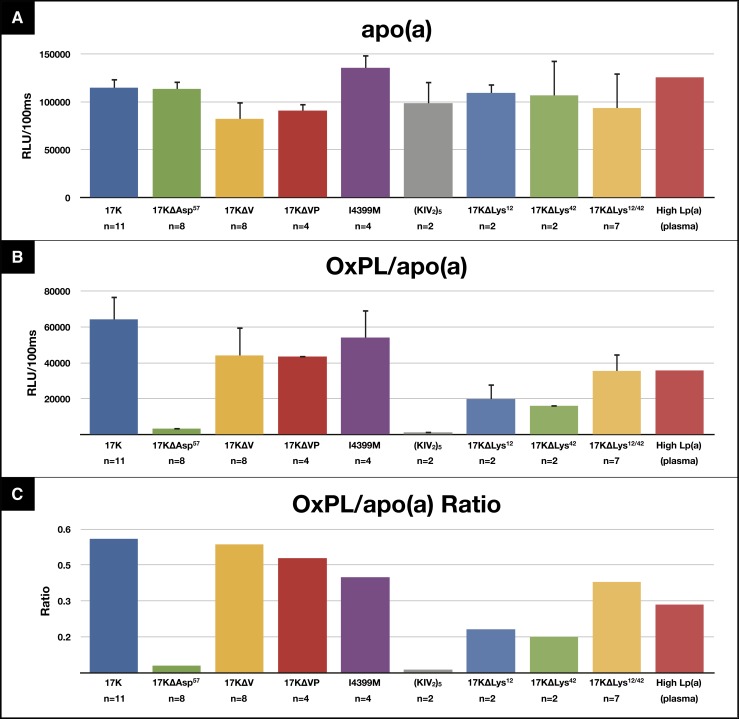

Determination of the presence of OxPLs on r-apo(a) constructs

ELISA of various r-apo(a) constructs was performed to detect the presence of OxPLs using E06. The r-apo(a) constructs were initially captured on microtiter well plates with LPA4 and the amount of apo(a) captured then detected by biotinylated LPA4. For all constructs shown, the levels of r-apo(a) captured in the wells were fairly similar (Fig. 7A). All constructs have evidence of OxPL immunoreactivity, except the 17KΔAsp57 and the (KIV2)5 constructs (Fig. 7B). OxPLs were clearly present in apo(a) captured from the 17K and 17KΔVP constructs, which are missing KV and KV and the protease domain respectively, the I4399M r-apo(a) construct, which represents the LPA single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs3798220 with an isoleucine to methionine substitution associated with CAD (45, 46) and high OxPL/apoB levels (47), and human plasma. No OxPLs were detectable on 17KΔAsp57 r-apo(a) (chimpanzee and gorilla variant) that contains KV but has a substitution of alanine to aspartate 57 on KIV10.

Fig. 7.

Assessment of the presence of OxPL on various r-apo(a) constructs via ELISA as shown in Fig. 2. I4399M = LPA SNP rs3798220 (single nucleotide polymorphism of the LPA gene that is associated with increased Lp(a) levels and an increased risk for CAD). High Lp(a) (plasma) = plasma from a healthy subject with high Lp(a) plasma levels (70 mg/dl).

Of note, Lys12 and Lys42 of KV had previously been postulated to bind OxPLs in both native apo(a) and r-apo(a) (13) based on computer modeling. However, constructs containing either mutation of Lys12 (17KΔLys12) or Lys42 (17KΔLys42) or both (17KΔLys12/42) on KV contained measurable levels of OxPLs, though the amounts bound were lower than other constructs. Indeed, constructs lacking KV altogether (17KΔV and 17KΔVP) had similar E06 reactivity as 17K.

Because the amounts of apo(a) captured on the plates were not identical for all constructs, we also determined the OxPL/apo(a) ratio (Fig. 7C) by dividing the OxPL content on the plate by apo(a) content on separate plates (i.e., data in Fig. 6B divided by data in Fig. 6A), which shows similar results to the raw data.

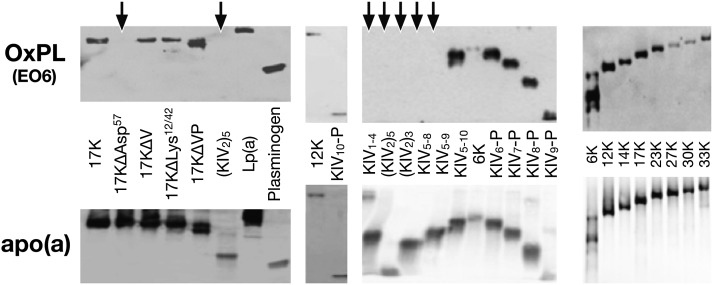

Determination of the presence of OxPLs on r-apo(a) constructs using immunoblotting

Immunoblotting of various r-apo(a) constructs on SDS-PAGE identified the key determinant of OxPL binding to be KIV10. OxPLs were present on Lp(a) and PLG, as expected, and on the r-apo(a) constructs 6K, 12K, 14K, 17K, 23K, 27K, 30K and 33K, 17KΔV, 17KΔVP, 17KΔLys12/42 as well as truncated variants from KIV6-P (KIV6 through protease domain) to KIV10-P. E06 immunoreactivity was not present on r-apo(a) consisting only of KIV1–4, (KIV2)5, or 17KΔAsp57, or on r-apo(a) constructs lacking KIV10 (Fig. 8). The presence of apo(a) in these constructs was confirmed in parallel gels.

Fig. 8.

Immunoblotting of various r-apo(a) constructs and human PLG with E06 for PC-OxPL and an anti-apo(a) antibody. Individual constructs are explained in detail in Fig. 2. Arrows indicate where E06 activity is not present. In these immunoblots OxPLs are denoted to reflect only E06-detectable OxPLs and not all OxPLs. RLU, relative light units.

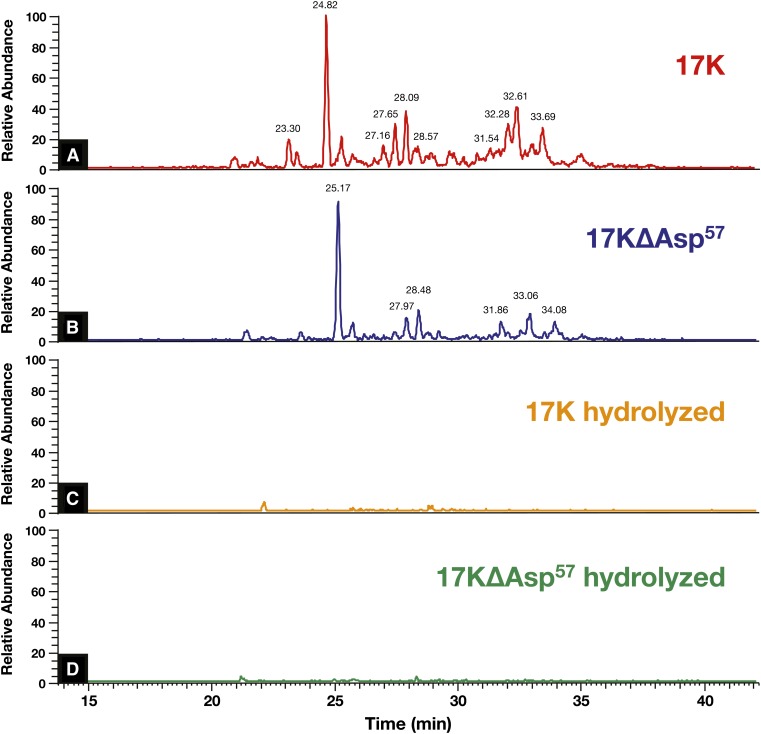

Determination of OxPLs on 17K WT and 17KΔAsp57 r-apo(a) constructs using LC-MS/MS

We next utilized LC-MS/MS to identify PC containing OxPLs on r-apo(a) constructs 17K and 17KΔAsp57. The presence of PC on OxPLs of trypsin digests of r-apo(a)s was assessed by PIS for m/z = 184, which is the signature of PC. A number of prominent peptide peaks containing PC were present in the LC-chromatogram in the 17K construct (Fig. 9A), indicating variously sized PC-modified peptides. Interestingly, the 17KΔAsp57 r-apo(a), despite having no E06 immunoreactivity, had a similar but not identical chromatogram (Fig. 9B). To rule out the possibility that the hydrolysis had destroyed the peptides themselves, we did full scan experiments on samples with and without NH4OH treatment and similar patterns of peptides were observed (data not shown). These PC adducts can be hydrolyzed under basic conditions as shown in Fig. 9C, D. These data strongly suggest that the peaks shown in Fig. 9A, B were indeed peptides with covalently modified PC species, not peptides that happen to have fragments with m/z 184 and thus misidentified, otherwise, they would have shown up in Fig. 9C, D.

Fig. 9.

Identification of OxPLs in r-apo(a) constructs. LC-MS/MS experiments on 17K (A), 17KΔAsp57 (B), and their hydrolyzed versions (C, D).

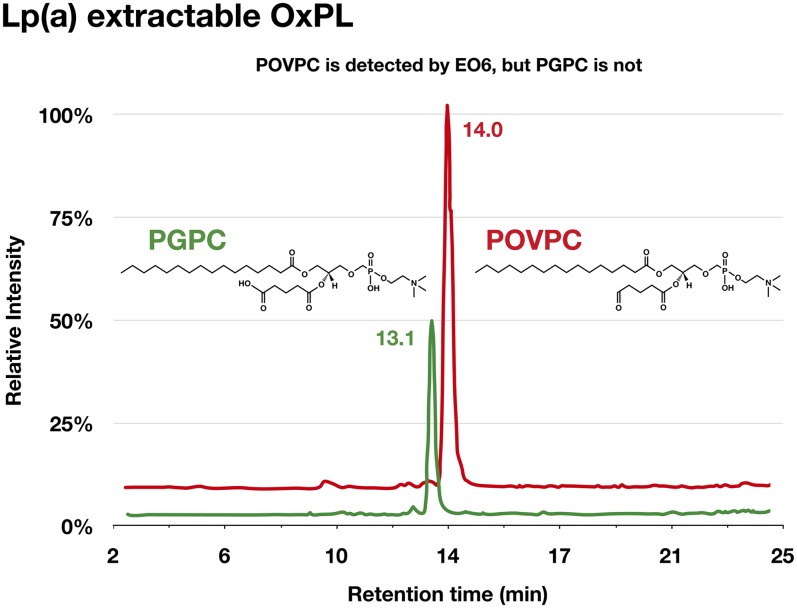

Determination of OxPLs in lipid phase of Lp(a) using LC-MS/MS following lipid extraction

We had previously demonstrated the ability to separate oxidized and nonoxidized species of varying polarities employing reverse phase LC-MS/MS, using a mixture of PC standards (Avanti Polar Lipids) such as POVPC, PGPC, PAzPC (1-palmitoyl-2-azelaoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine), ALDO-PC (1-palmitoyl-2-(9′-oxo-nonanoyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine), and DLPC (1,2-dilinoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine) (41, 43, 44). We have applied this methodology to identify noncovalently bound OxPLs on Lp(a) derived from three normal donors with Lp(a) levels ∼90 mg/dl.

Lp(a) was isolated by density gradient ultracentrifugation followed by NaCl/ϵ-aminocaproic acid elution on lysine Sepharose. The purified Lp(a) was then extracted with 2:1 chloroform:methanol and the organic phase run on LC-MS/MS. Prominent peaks in the Lp(a) organic phase extract, but not in the aqueous phase, were positively identified as POVPC and PGPC using appropriate standards (Fig. 10). POVPC is known to be detected by E06, but PGPC is not (38), confirming that Lp(a) contains lipid phase E06-detectable and E06-nondetectable OxPLs.

Fig. 10.

Determination of PC containing OxPLs in organic phase of isolated of Lp(a) following lipid extraction using LC-MS/MS. Data represent findings from three normal donors with Lp(a) levels ∼90 mg/dl.

DISCUSSION

In this study we demonstrate several novel observations in the relationship between OxPLs and Lp(a): 1) Among all the species tested that have circulating Lp(a), only human Lp(a) contains OxPLs detectable by monoclonal antibody E06; 2) The PC-OxPLs in human Lp(a) are both covalently bound to apo(a) and also extractable from the lipid phase; 3) Lp(a) transgenic mice expressing a modified human Lp(a) with an intact KIV10 LBS and the presence of KV contained E06-detectable OxPLs, whereas Lp(a) transgenic mice expressing a very similar apo(a) construct, but in which two critical amino acids of the LBS of apo(a) were modified, did not contain E06-detectable OxPLs. These data, along with similar results in selected r-apo(a) constructs, support the hypothesis that the KIV10 LBS, along with its well-known property of mediating fibrin binding (35, 48), influences covalent binding of OxPLs to apo(a); 4) Lp(a) contains both E06-detectable (POVPC) and nonEO6-detectable (PGPC) OxPLs, consistent with its ability to bind a variety of OxPLs; and 5) PC-containing OxPLs were shown to be present by LC-MS/MS on the natural human 17K r-apo(a), consistent with the ability of E06 to bind to this construct. The observation that saponification removed the PC signal from the peptides suggests that this PC was indeed part of a covalently linked OxPL. Surprisingly, however, we also found peptides containing PC in the 17KΔAsp57 construct, which represents a mutation present in the chimpanzee and gorilla, and which were not detected by E06 binding, suggesting either the presence of nonE06-detectable OxPLs or a steric hindrance mediated by the change in the LBS preventing E06 from detecting such OxPLs. Overall, these observations have implications for understanding the role of OxPLs in binding to Lp(a) and mediating human CVD.

Prior studies in transgenic mice have shown that modification of the LBS in KIV10 results in reduced focal accumulation of apo(a) in mouse aorta following high cholesterol diet (35, 48). Modifications of this binding pocket are present in all apes and monkeys studied, except the baboon and orangutan, and the apo(a)/Lp(a) from these species does not have EO6 immunoreactivity on ELISA. In most baboons, an intact LBS on apo(a) is functionally present that is similar to the human apo(a) that binds lysine. However, baboon Lp(a), as opposed to apo(a), does not bind to lysine or to plasmin-modified fibrinogen (49). Interestingly, KV is absent in baboon apo(a) and thus, in baboon Lp(a) the absence of KV appears to prevent access to lysine resides in the KIV10 LBS due to altered apo(a) confirmation causing steric hindrance (49). Even in humans, significant lysine binding heterogeneity of apo(a) exists among different subjects, and part of this heterogeneity may be mediated by noncovalent associations of Lp(a) with other circulating proteins that may mask the KIV10 LBS (50, 51).

The role of KIV10 LBS in mediating binding of OxPLs was further documented by lack of E06 immunoreactivity in r-apo(a) constructs that were designed with various changes in the LBS and other K sites, as well by lack of E06 immunoreactivity in Lp(a) of mice expressing an LBS− apo(a) transgene. In previous studies (13), it was suggested by enzymatic digestion of human apo(a) that KV was the site containing contained OxPLs and that rhesus monkey apo(a), which does not contain KV, had no OxPLs, as demonstrated by lack of E06 immunoreactivity. Computer modeling further suggested that Lys12 and Lys42 of KV covalently bound OxPLs, but no experimental confirmation of the data were presented and nonhuman primate apo(a) containing KV was not evaluated. In contrast, our current results show that the presence of KV is not necessary for OxPL binding, as r-apo(a) constructs lacking KV had strong E06 immunoreactivity. Furthermore, chimpanzees (and bonobos) that have KV did not show E06 immunoreactivity, a finding that seems to be explained by their KIV10 Asp57→Ala57 substitution compared with human apo(a). This observation does not appear to be due to lack of circulating OxPLs, as cholesterol- and fat-fed cynomolgus monkeys with total plasma cholesterol ∼700 mg/dl and abundant E06-detectable OxPLs in atherosclerotic lesions also do not have E06-detectable OxPLs on Lp(a), as shown previously (34), but they do on PLG which has an intact KIV10 LBS compared with Lp(a) (25). In addition, cynomolgus monkeys do carry OxPLs on apoB particles, as previously shown (34).

In general, the most likely amino acids binding OxPLs are cysteines, lysines, and histidines. The seven amino acids that define the KIV10 LBS do not have terminal amines or cysteines and are unlikely themselves to bind OxPLs. There are no lysines in KIV10 in human apo(a) (see Fig. 2) and all six cysteines are occupied in disulfide bonds. Therefore, it appears that histidines, of which there are three in KIV10, are the likely sites that bind OxPLs in KIV10 in human apo(a). In particular, His31 and His33, which flank Arg32, are strong candidates for binding OxPLs. Compared with humans and gorillas, all other species with apo(a) have an Arg to Gln substitution at amino acid position 32 in KIV10. Previous modeling studies (49) suggested that Arg32, which is substituted in all other Ks in human apo(a) (4), quite markedly alters the conformation of this K that may allow the histidines to bind OxPLs. Further work removing the entire KIV10 and/or utilizing site-specific mutagenesis of likely sites will be needed to identify the exact amino acids involved in the covalent binding of OxPLs.

An important finding in this study was that OxPLs are not only present covalently on apo(a) but are also present in the lipid phase of Lp(a). We previously showed that E06 immunoreactivity was present in organic extracts of human Lp(a) (16). Now utilizing LC-MS/MS analyses of organic extracts of human Lp(a), we confirm that specific OxPLs are present, such as POVPC, which is recognized by EO6, as well as PGPC, which is not recognized by E06 as previously documented (38). This demonstrates that there are OxPLs present in Lp(a) that are not recognized by E06 and suggests that the ability of Lp(a) to bind various OxPLs is a generalized property. The relative amounts of OxPLs on apo(a) versus Lp(a) have not been fully established and may vary according to underlying disease states. Indeed, we found previously that the amount of E06-detectable OxPLs in organic extracts of human Lp(a) varied considerably, with ∼30–70% of E06 immunoreactivity in Lp(a) from various subjects being lipid soluble (16).

The r-apo(a) constructs contained covalently bound OxPLs. We speculate that the OxPLs on the r-apo(a) constructs are likely derived from OxPLs generated from apoptotic cells in cell culture (52). In vivo, OxPLs on Lp(a) may be derived from hepatocytes during Lp(a) assembly, particularly if there is enhanced hepatocyte oxidative stress, such as in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (53), or transferred to Lp(a) in plasma from atherosclerotic plaques, as suggested by prior human studies in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (22, 54). Importantly, however, our studies of OxPLs on apo(a), expressed both in cell culture and found in mouse plasma, show a similar dependence on an intact LBS in KIV10, suggesting that the OxPLs acquired by apo(a) in vitro are a relevant model for those acquired by the apo(a) component of Lp(a) in vivo.

A summary of the differences in Ks, attachment to LDL, protease activity, fibrin binding, and OxPL binding in PLG and apo(a) is given in Fig. 11. The evolution of Lp(a) in apes and monkeys from PLG has occurred concomitantly with losing the lysine binding properties of the KIV10 LBS. This has occurred through a variety of mechanisms, including loss of KV and/or modifications of KIV10 LBS (49, 55, 56). Along with loss of lysine binding, these species also do not have E06 immunoreactivity on Lp(a). Interestingly, we recently showed that humans, apes, monkeys, and lower species such as mice do have OxPLs on circulating PLG, which is not known to have similar LBS substitutions as apo(a), and that the presence of OxPLs on PLG actually mediates more optimal fibrinolysis (25). Thus, the presence of OxPLs on PLG would be expected to be protective against atherothrombosis, as opposed to OxPLs on Lp(a) being pro-atherogenic. This suggests that during evolution, human Lp(a), as opposed to Lp(a) on other species, has further evolved from ape and monkey Lp(a) by regaining the ability to both bind lysine through the KV10 LBS and also to overtly capture E06-detectable OxPLs.

Fig. 11.

Summary of differences in E06 immunoreactivity of various species. A: Depicts the presence of KIII, KIV variants, KV, and the protease domain of apo(a) from various species and human PLG. B: Depicts the key amino acids of the functionally intact LBS of KIV of PLG, the conservative substitution of KIV10 of human apo(a), and two individual amino acid substitutions in monkeys, apes, and rare human mutations that render the LBS defective.

We have previously shown that the PC of OxPLs present on OxPLs of OxLDL, or apoptotic cells or apoptotic blebs and debris represents a “danger associated molecular pattern” (57), which is recognized by a variety of innate “pattern recognition receptors” such as natural antibodies (58), scavenger receptors, e.g., CD36 (39) and C-reactive protein (59). Each of these pattern recognition receptors can bind and/or scavenge PC containing OxPLs, which are pro-inflammatory. In support of this, Lp(a) and its associated OxPLs were recently shown to trigger apoptosis in endoplasmic reticulum-stressed macrophages through a mechanism requiring both CD36 and Toll-like receptor 2 (40). In a similar manner, malondialdehyde epitopes, which represent another well-described oxidation-specific epitope resulting from lipid peroxidation, are bound by complement factor H, which protects against the oxidative stress that may mediate age-related macular degeneration (60). In future studies, demonstration of human “E06”-like antibodies may provide additional insights into the role of OxPLs in humans as danger-associated molecular patterns and the response of the adaptive and innate immune systems in removing them to protect the host (57, 61, 62).

It is now well-established that high levels of Lp(a) are a major risk factor for CAD (11). Lp(a) has an increased affinity for the extracellular matrix of the intima compared with LDL, and one can envision that the enhanced content of OxPLs would make Lp(a) even more pro-inflammatory. It was previously shown that the LBS of human Lp(a) is a key component in mediating the accumulation of Lp(a) in the intima as well, and in mediating enhanced fatty streak formation (35, 48). As shown in this study, such LBS intact Lp(a) as found in humans would also be enriched in OxPLs. This would lead to the hypothesis that an Lp(a) with loss of the LBS would also be associated with in an inability to bind OxPLs and this would be less atherogenic. Studies are underway in the LBS− apo(a)/Lp(a) to assess whether they have less atherogenesis than WT apo(a)/Lp(a) mice with similar Lp(a) levels. Future studies will also need to dissociate LBS features of apo(a) along with the lack of E06 immunoreactivity to assess whether the reduced atherogenesis is due to the defective LBS or the failure to contain OxPLs.

Limitations of this study include the lack of adequate nonhuman primate plasma to perform comprehensive studies such as isolation of Lp(a), immunoblotting, or LC-MS/MS of lipid extracts to directly assess for the presence of OxPLs. Whether these species carry OxPLs on other proteins cannot be determined at present. However, the r-apo(a) constructs used covered the key differences in apo(a) present in apes and monkeys compared with humans and may potentially be considered appropriate apo(a) surrogates.

In summary, E06- and nonE06-detectable PC containing OxPLs are present in the lipid phase of Lp(a) and covalently bound to apo(a). E06 immunoreactivity is strongly influenced by the KIV10 LBS and is unique to human Lp(a), which may explain its pro-atherogenic potential. Human clinical trials with potent Lp(a) lowering agents, that also may reduce their OxPL content (31, 32), will provide the ultimate evidence of the atherogenicity of Lp(a) (63).

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- ALDO-PC

- 1-palmitoyl-2-(9′-oxo-nonanoyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- AzPC

- 1-palmitoyl-2-azelaoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- CAD

- coronary artery disease

- CVD

- cardiovascular disease

- DLPC

- 1,2-dilinoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- K

- kringle

- LBS

- lysine binding site

- Lp(a)

- lipoprotein (a)

- LPA

- gene encoding apo(a)

- OxPL

- oxidized phospholipid

- PC

- phosphocholine

- PEIPC

- epoxy-isoprostane-phosphocholine

- PGPC

- 1-palmitoyl-2-glutaroyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- PIS

- precursor ion scanning

- PLG

- plasminogen

- r-apo(a)

- recombinant apo(a)

- POVPC

- 1-palmitoyl-2-(5-oxovaleroyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- WT

- wild-type

This study was funded by a grant from the Fondation Leducq, HL-088093 and HL-055798 (S.T., J.L.W.), the Swiss National Science Foundation PBBSP3-124742 and the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences PASMP3_132566 (G.L.), National Institutes of Health Grants GM-15431 and GM-69338 (J.L.W.), CAS (2012OHTP07) and ES013125 (H.Y.), and CIHR MOP11272 and HSFO T5916 (M.L.K). S.T. and J.L.W. are inventors of patents owned by the University of California for the commercial use of oxidation-specific antibodies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dubé J. B., Boffa M. B., Hegele R. A., Koschinsky M. L. 2012. Lipoprotein(a): more interesting than ever after 50 years. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 23: 133–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoover-Plow J., Huang M. 2013. Lipoprotein(a) metabolism: potential sites for therapeutic targets. Metabolism. 62: 479–491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kronenberg F., Utermann G. 2013. Lipoprotein(a): resurrected by genetics. J. Intern. Med. 273: 6–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McLean J. W., Tomlinson J. E., Kuang W. J., Eaton D. L., Chen E. Y., Fless G. M., Scanu A. M., Lawn R. M. 1987. cDNA sequence of human apolipoprotein(a) is homologous to plasminogen. Nature. 330: 132–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawn R. M., Boonmark N. W., Schwartz K., Lindahl G. E., Wade D. P., Byrne C. D., Fong K. J., Meer K., Patthy L. 1995. The recurring evolution of lipoprotein(a). Insights from cloning of hedgehog apolipoprotein(a). J. Biol. Chem. 270: 24004–24009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsimikas S., Mallat Z., Talmud P. J., Kastelein J. J., Wareham N. J., Sandhu M. S., Miller E. R., Benessiano J., Tedgui A., Witztum J. L., et al. 2010. Oxidation-specific biomarkers, lipoprotein(a), and risk of fatal and nonfatal coronary events. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 56: 946–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erqou S., Thompson A., Di Angelantonio E., Saleheen D., Kaptoge S., Marcovina S., Danesh J. 2010. Apolipoprotein(a) isoforms and the risk of vascular disease: systematic review of 40 studies involving 58,000 participants. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 55: 2160–2167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration, Ergou S., Kaptoge S., Perry P. L., Di Angelantonio E., Thompson A., White I. R., Marcovina S. M., Collins R., Thompson S. G., Danesh J. 2009. Lipoprotein(a) concentration and the risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and nonvascular mortality. JAMA. 302: 412–423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clarke R., Peden J. F., Hopewell J. C., Kyriakou T., Goel A., Heath S. C., Parish S., Barlera S., Franzosi M. G., Rust S., et al. ; PROCARDIS Consortium 2009. Genetic variants associated with Lp(a) lipoprotein level and coronary disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 361: 2518–2528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamstrup P. R., Tybjaerg-Hansen A., Steffensen R., Nordestgaard B. G. 2009. Genetically elevated lipoprotein(a) and increased risk of myocardial infarction. JAMA. 301: 2331–2339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsimikas S., Hall J. H. 2012. Lipoprotein(a) as a potential causal genetic risk factor of cardiovascular disease: a rationale for increased efforts to understand its pathophysiology and develop targeted therapies. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 60: 716–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsimikas S., Bergmark C., Beyer R. W., Patel R., Pattison J., Miller E., Juliano J., Witztum J. L. 2003. Temporal increases in plasma markers of oxidized low-density lipoprotein strongly reflect the presence of acute coronary syndromes. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 41: 360–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edelstein C., Pfaffinger D., Hinman J., Miller E., Lipkind G., Tsimikas S., Bergmark C., Getz G. S., Witztum J. L., Scanu A. M. 2003. Lysine-phosphatidylcholine adducts in kringle V impart unique immunological and potential pro-inflammatory properties to human apolipoprotein(a). J. Biol. Chem. 278: 52841–52847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsimikas S., Brilakis E. S., Miller E. R., McConnell J. P., Lennon R. J., Kornman K. S., Witztum J. L., Berger P. B. 2005. Oxidized phospholipids, Lp(a) lipoprotein, and coronary artery disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 353: 46–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsimikas S., Witztum J. L. 2008. The role of oxidized phospholipids in mediating lipoprotein(a) atherogenicity. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 19: 369–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bergmark C., Dewan A., Orsoni A., Merki E., Miller E. R., Shin M. J., Binder C. J., Horkko S., Krauss R. M., Chapman M. J., et al. 2008. A novel function of lipoprotein [a] as a preferential carrier of oxidized phospholipids in human plasma. J. Lipid Res. 49: 2230–2239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taleb A., Witztum J. L., Tsimikas S. 2011. Oxidized phospholipids on apolipoprotein B-100 (OxPL/apoB) containing lipoproteins: a biomarker predicting cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular events. Biomark. Med. 5: 673–694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Dijk R. A., Kolodgie F., Ravandi A., Leibundgut G., Hu P. P., Prasad A., Mahmud E., Dennis E., Curtiss L. K., Witztum J. L., et al. 2012. Differential expression of oxidation-specific epitopes and apolipoprotein(a) in progressing and ruptured human coronary and carotid atherosclerotic lesions. J. Lipid Res. 53: 2773–2790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fefer P., Tsimikas S., Segev A., Sparkes J., Otsuma F., Kolodgie F., Virmani R., Juliano J., Charron T., Strauss B. H. 2012. The role of oxidized phospholipids, lipoprotein (a) and biomarkers of oxidized lipoproteins in chronically occluded coronary arteries in sudden cardiac death and following successful percutaneous revascularization. Cardiovasc. Revasc. Med. 13: 11–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsimikas S., Kiechl S., Willeit J., Mayr M., Miller E. R., Kronenberg F., Xu Q., Bergmark C., Weger S., Oberhollenzer F., et al. 2006. Oxidized phospholipids predict the presence and progression of carotid and femoral atherosclerosis and symptomatic cardiovascular disease: five-year prospective results from the Bruneck study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 47: 2219–2228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gong Y., Hoover-Plow J. 2012. The plasminogen system in regulating stem cell mobilization. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012: 437920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsimikas S., Lau H. K., Han K. R., Shortal B., Miller E. R., Segev A., Curtiss L. K., Witztum J. L., Strauss B. H. 2004. Percutaneous coronary intervention results in acute increases in oxidized phospholipids and lipoprotein(a): short-term and long-term immunologic responses to oxidized low-density lipoprotein. Circulation. 109: 3164–3170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kiechl S., Willeit J., Mayr M., Viehweider B., Oberhollenzer M., Kronenberg F., Wiedermann C. J., Oberthaler S., Xu Q., Witztum J. L., et al. 2007. Oxidized phospholipids, lipoprotein(a), lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 activity, and 10-year cardiovascular outcomes: prospective results from the Bruneck study. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 27: 1788–1795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsimikas S., Willeit P., Willeit J., Santer P., Mayr M., Xu Q., Mayr A., Witztum J. L., Kiechl S. 2012. Oxidation-specific biomarkers, prospective 15-year cardiovascular and stroke outcomes, and net reclassification of cardiovascular events. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 60: 2218–2229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leibundgut G., Arai K., Orsoni A., Yin H., Scipione C., Miller E. R., Koschinsky M. L., Chapman M. J., Witztum J. L., Tsimikas S. 2012. Oxidized phospholipids are present on plasminogen, affect fibrinolysis, and increase following acute myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 59: 1426–1437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mulichak A. M., Tulinsky A., Ravichandran K. G. 1991. Crystal and molecular structure of human plasminogen kringle 4 refined at 1.9-A resolution. Biochemistry. 30: 10576–10588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koschinsky M. L., Tomlinson J. E., Zioncheck T. F., Schwartz K., Eaton D. L., Lawn R. M. 1991. Apolipoprotein(a): expression and characterization of a recombinant form of the protein in mammalian cells. Biochemistry. 30: 5044–5051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sangrar W., Koschinsky M. L. 2000. Characterization of the interaction of recombinant apolipoprotein(a) with modified fibrinogen surfaces and fibrin clots. Biochem. Cell Biol. 78: 519–525 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hancock M. A., Boffa M. B., Marcovina S. M., Nesheim M. E., Koschinsky M. L. 2003. Inhibition of plasminogen activation by lipoprotein(a): critical domains in apolipoprotein(a) and mechanism of inhibition on fibrin and degraded fibrin surfaces. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 23260–23269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feric N. T., Boffa M. B., Johnston S. M., Koschinsky M. L. 2008. Apolipoprotein(a) inhibits the conversion of Glu-plasminogen to Lys-plasminogen: a novel mechanism for lipoprotein(a)-mediated inhibition of plasminogen activation. J. Thromb. Haemost. 6: 2113–2120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Merki E., Graham M. J., Mullick A. E., Miller E. R., Crooke R. M., Pitas R. E., Witztum J. L., Tsimikas S. 2008. Antisense oligonucleotide directed to human apolipoprotein B-100 reduces lipoprotein(a) levels and oxidized phospholipids on human apolipoprotein B-100 particles in lipoprotein(a) transgenic mice. Circulation. 118: 743–753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Merki E., Graham M., Taleb A., Leibundgut G., Yang X., Miller E. R., Fu W., Mullick A. E., Lee R., Willeit P., et al. 2011. Antisense oligonucleotide lowers plasma levels of apolipoprotein (a) and lipoprotein (a) in transgenic mice. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 57: 1611–1621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schneider M., Witztum J. L., Young S. G., Ludwig E. H., Miller E. R., Tsimikas S., Curtiss L. K., Marcovina S. M., Taylor J. M., Lawn R. M., et al. 2005. High-level lipoprotein [a] expression in transgenic mice: evidence for oxidized phospholipids in lipoprotein [a] but not in low density lipoproteins. J. Lipid Res. 46: 769–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsimikas S., Aikawa M., Miller F. J., Jr, Miller E. R., Torzewski M., Lentz S. R., Bergmark C., Heistad D. D., Libby P., Witztum J. L. 2007. Increased plasma oxidized phospholipid:apolipoprotein B-100 ratio with concomitant depletion of oxidized phospholipids from atherosclerotic lesions after dietary lipid-lowering: a potential biomarker of early atherosclerosis regression. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 27: 175–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boonmark N. W., Lou X. J., Yang Z. J., Schwartz K., Zhang J. L., Rubin E. M., Lawn R. M. 1997. Modification of apolipoprotein(a) lysine binding site reduces atherosclerosis in transgenic mice. J. Clin. Invest. 100: 558–564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skålén K., Gustafsson M., Rydberg E. K., Hultén L. M., Wiklund O., Innerarity T. L., Borén J. 2002. Subendothelial retention of atherogenic lipoproteins in early atherosclerosis. Nature. 417: 750–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Szapacs M. E., Kim H. Y., Porter N. A., Liebler D. C. 2008. Identification of proteins adducted by lipid peroxidation products in plasma and modifications of apolipoprotein A1 with a novel biotinylated phospholipid probe. J. Proteome Res. 7: 4237–4246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Friedman P., Horkko S., Steinberg D., Witztum J. L., Dennis E. A. 2002. Correlation of antiphospholipid antibody recognition with the structure of synthetic oxidized phospholipids. Importance of Schiff base formation and aldol condensation. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 7010–7020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boullier A., Friedman P., Harkewicz R., Hartvigsen K., Green S. R., Almazan F., Dennis E. A., Steinberg D., Witztum J. L., Quehenberger O. 2005. Phosphocholine as a pattern recognition ligand for CD36. J. Lipid Res. 46: 969–976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seimon T. A., Nadolski M. J., Liao X., Magallon J., Nguyen M., Feric N. T., Koschinsky M. L., Harkewicz R., Witztum J. L., Tsimikas S., et al. 2010. Atherogenic lipids and lipoproteins trigger CD36-TLR2-dependent apoptosis in macrophages undergoing endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Metab. 12: 467–482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watson A. D., Leitinger N., Navab M., Faull K. F., Horkko S., Witztum J. L., Palinski W., Schwenke D., Salomon R. G., Sha W., et al. 1997. Structural identification by mass spectrometry of oxidized phospholipids in minimally oxidized low density lipoprotein that induce monocyte/endothelial interactions and evidence for their presence in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 13597–13607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watson A. D. 2006. Systems biology approaches to metabolic and cardiovascular disorders. Lipidomics: a global approach to lipid analysis in biological systems. J. Lipid Res. 47: 2101–2111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fang L., Harkewicz R., Hartvigsen K., Wiesner P., Choi S. H., Almazan F., Pattison J., Deer E., Sayaphupha T., Dennis E. A., et al. 2010. Oxidized cholesteryl esters and phospholipids in zebrafish larvae fed a high cholesterol diet: macrophage binding and activation. J. Biol. Chem. 285: 32343–32351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harkewicz R., Hartvigsen K., Almazan F., Dennis E. A., Witztum J. L., Miller Y. I. 2008. Cholesteryl ester hydroperoxides are biologically active components of minimally oxidized low density lipoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 283: 10241–10251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luke M. M., Kane J. P., Liu D. M., Rowland C. M., Shiffman D., Cassano J., Catanese J. J., Pullinger C. R., Leong D. U., Arellano A. R., et al. 2007. A polymorphism in the protease-like domain of apolipoprotein(a) is associated with severe coronary artery disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 27: 2030–2036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li Y., Luke M. M., Shiffman D., Devlin J. J. 2011. Genetic variants in the apolipoprotein(a) gene and coronary heart disease. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 4: 565–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arai K., Luke M. M., Koschinsky M. L., Miller E. R., Pullinger C. R., Witztum J. L., Kane J. P., Tsimikas S. 2010. The I4399M variant of apolipoprotein(a) is associated with increased oxidized phospholipids on apolipoprotein B-100 particles. Atherosclerosis. 209: 498–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hughes S. D., Lou X. J., Ighani S., Verstuyft J., Grainger D. J., Lawn R. M., Rubin E. M. 1997. Lipoprotein(a) vascular accumulation in mice. In vivo analysis of the role of lysine binding sites using recombinant adenovirus. J. Clin. Invest. 100: 1493–1500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Belczewski A. R., Ho J., Taylor F. B., Jr, Boffa M. B., Jia Z., Koschinsky M. L. 2005. Baboon lipoprotein(a) binds very weakly to lysine-agarose and fibrin despite the presence of a strong lysine-binding site in apolipoprotein(a) kringle IV type 10. Biochemistry. 44: 555–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xia J., May L. F., Koschinsky M. L. 2000. Characterization of the basis of lipoprotein [a] lysine-binding heterogeneity. J. Lipid Res. 41: 1578–1584 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scanu A. M., Pfaffinger D., Lee J. C., Hinman J. 1994. A single point mutation (Trp72→Arg) in human apo(a) kringle 4-37 associated with a lysine binding defect in Lp(a). Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1227: 41–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chang M. K., Binder C. J., Miller Y. I., Subbanagounder G., Silverman G. J., Berliner J. A., Witztum J. L. 2004. Apoptotic cells with oxidation-specific epitopes are immunogenic and proinflammatory. J. Exp. Med. 200: 1359–1370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bieghs V., Walenbergh S. M., Hendrikx T., van Gorp P. J., Verheyen F., Olde Damink S. W., Masclee A. A., Koek G. H., Hofker M. H., Binder C. J., et al. 2013. Trapping of oxidized LDL in lysosomes of Kupffer cells is a trigger for hepatic inflammation. Liver Int. 33: 1056–1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ravandi A., Harkewicz R., Leibundgut G., Miller Y. I., Dennis E. A., Witztum J. L., Tsimikas S. 2011. Identification of oxidized phospholipids and cholesteryl esters in embolic protection devices post percutaneous coronary, carotid and peripheral interventions in humans. (Poster P385 at ATVB 2011 Scientific Sessions. April 28–30, 2011; Chicago, IL). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chenivesse X., Huby T., Wickins J., Chapman J., Thillet J. 1998. Molecular cloning of the cDNA encoding the carboxy-terminal domain of chimpanzee apolipoprotein(a): an Asp57→Asn mutation in kringle IV-10 is associated with poor fibrin binding. Biochemistry. 37: 7213–7223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Scanu A. M., Miles L. A., Fless G. M., Pfaffinger D., Eisenbart J., Jackson E., Hoover-Plow J. L., Brunck T., Plow E. F. 1993. Rhesus monkey lipoprotein(a) binds to lysine Sepharose and U937 monocytoid cells less efficiently than human lipoprotein(a). Evidence for the dominant role of kringle 4(37). J. Clin. Invest. 91: 283–291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Miller Y. I., Choi S. H., Wiesner P., Fang L., Harkewicz R., Hartvigsen K., Boullier A., Gonen A., Diehl C. J., Que X., et al. 2011. Oxidation-specific epitopes are danger-associated molecular patterns recognized by pattern recognition receptors of innate immunity. Circ. Res. 108: 235–248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hartvigsen K., Chou M. Y., Hansen L. F., Shaw P. X., Tsimikas S., Binder C. J., Witztum J. L. 2009. The role of innate immunity in atherogenesis. J. Lipid Res. 50(Suppl): S388–S393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chang M. K., Binder C. J., Torzewski M., Witztum J. L. 2002. C-reactive protein binds to both oxidized LDL and apoptotic cells through recognition of a common ligand: Phosphorylcholine of oxidized phospholipids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99: 13043–13048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weismann D., Hartvigsen K., Lauer N., Bennett K. L., Scholl H. P., Charbel Issa P., Cano M., Brandstatter H., Tsimikas S., Skerka C., et al. 2011. Complement factor H binds malondialdehyde epitopes and protects from oxidative stress. Nature. 478: 76–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lichtman A. H., Binder C. J., Tsimikas S., Witztum J. L. 2013. Adaptive immunity in atherogenesis: new insights and therapeutic approaches. J. Clin. Invest. 123: 27–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Leibundgut G., Witztum J. L., Tsimikas S. 2013. Oxidation-specific epitopes and immunological responses translational biotheranostic implications for atherosclerosis. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kolski B., Tsimikas S. 2012. Emerging therapeutic agents to lower lipoprotein (a) levels. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 23: 560–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]