Abstract

Interindividual variability in the response of plasma triglyceride concentrations (TG) following fish oil consumption has been observed. Our objective was to examine the associations between single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within genes encoding proteins involved in de novo lipogenesis and the relative change in plasma TG levels following a fish oil supplementation. Two hundred and eight participants were recruited in the greater Quebec City area. The participants completed a six-week fish oil supplementation (5 g fish oil/day: 1.9–2.2 g eicosapentaenoic acid and 1.1 g docosahexaenoic acid. SNPs within SREBF1, ACLY, and ACACA genes were genotyped using TAQMAN methodology. After correction for multiple comparison, only two SNPs, rs8071753 (ACLY) and rs1714987 (ACACA), were associated with the relative change in plasma TG concentrations (P = 0.004 and P = 0.005, respectively). These two SNPs explained 7.73% of the variance in plasma TG relative change following fish oil consumption. Genotype frequencies of rs8071753 according to the TG response groups (responders versus nonresponders) were different (P = 0.02). We conclude that the presence of certain SNPs within genes, such as ACLY and ACACA, encoding proteins involved in de novo lipogenesis seem to influence the plasma TG response following fish oil consumption.

Keywords: omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, fatty acid biosynthesis, SREBF1, ACACA, ACLY, interindividual variability

In Canada, cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the second leading cause of mortality after cancer (1). Many risk factors contribute to increase the risk of developing CVD. Among them, plasma triglyceride (TG) concentrations have been debated about whether they should be considered as an independent CVD risk factor. A review by Morisson et al. (2) indicated that plasma TG concentrations are an independent risk factor of coronary events in individuals without previous history of coronary heart disease (CHD). Plasma TG concentrations was the parameter of the metabolic syndrome the most strongly and independently associated with myocardial infarction and stroke (3). However, a recent meta-analysis has demonstrated no independent association between plasma TG concentrations and CVD risk (4). Still, the presence of high plasma TG concentrations is an important biomarker indicating alterations of lipid metabolism.

Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFAs) have been proven as an effective way to reduce plasma TG concentrations (5). However, a large interindividual variability has been observed in plasma TG concentration response following n-3 PUFA supplementation (6–8). A decrease in de novo lipogenesis is one of a few pathways that could explain the n-3 PUFA plasma TG-lowering effects. Lipogenesis is strongly regulated by the transcription factor sterol regulatory element-binding transcription factor 1 (SREBF1) (9). n-3 PUFA decrease the expression of SREBF1 (10, 11). SREBF1 regulates the activity of several lipogenic genes, such as ATP citrate lyase (ACLY) and acetyl-CoA carboxylase α (ACACA). ACLY is the primary enzyme responsible for the synthesis of acetyl-CoA in the cytosol (12). Acetyl-CoA may then be transformed by ACACA to malonyl-CoA, which is the first product in fatty acid biosynthesis (13). Only a few polymorphisms within these genes have been studied. SREBF1, gly952gly (rs2297508), has been associated with obesity, type 2 diabetes, and serum lipids (14–16), whereas a few single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) within ACACA gene (rs1266175 and rs2229416) were associated with plasma TG concentrations after the intake of certain antipsychotic drugs (17). The effects of SNPs within these genes on plasma TG concentrations have never been studied in the context of n-3 PUFA supplementation. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to examine the associations between polymorphisms in genes involved in the lipogenesis pathway and the plasma TG response following a marine n-3 PUFA supplementation.

METHODS

Subjects

A total of 254 unrelated subjects were recruited to participate in this clinical trial from the greater Quebec City metropolitan area between September 2009 and December 2011 through advertisements in local newspapers as well as by electronic messages sent to university students/employees. It was determined that a group of 152 participants was sufficient to provide an 80% probability and a 5% significance level of detecting an anticipated difference of 0.25 mmol/l in plasma TG concentrations after six weeks of fish oil supplementation with a genetic variation occurring in a relatively low frequency (5%) of the population. To be eligible, subjects had to be nonsmokers and free of any thyroid or metabolic disorders requiring treatment, such as diabetes, hypertension, severe dyslipidemia, or coronary heart disease. Participants had to be between ages 18 and 50 years and with a body mass index (BMI) between 25 and 40 kg/m2. The subjects who had taken n-3 PUFA supplements during the six months preceding the study were excluded. A total of 210 subjects completed the n-3 PUFA supplementation period. However, plasma TG concentrations were available for 208 participants, and thus the analyses were conducted on 208 participants. The experimental protocol was approved by the ethics committees of Laval University Hospital Research Center and Laval University. This clinical trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01343342). Informed, written consent was obtained from all the study subjects.

Study design and diets

Subjects followed a run-in period of two weeks. Individual dietary instructions were given by a trained dietitian to achieve the recommendations from Canada's Food Guide. Subjects were asked to follow these dietary recommendations and maintain their body weight stable throughout the research protocol. Some specifications were given regarding the n-3 PUFA dietary intakes: not to exceed two fish or seafood servings per week, to prefer white-flesh fishes instead of fatty fishes (examples were given), and to avoid enriched n-3 PUFA dietary products, such as some milks, juices, breads, and eggs. Subjects were also asked to limit their alcohol consumption during the protocol: two regular drinks per week were allowed. In addition, subjects were not allowed to take n-3 PUFA supplements (such as flaxseed), vitamins, or any natural health products during the protocol.

After the two-week run-in period, each participant received a bottle containing n-3 PUFA capsules for the next six weeks. They were instructed to take five capsules (1 g of fish oil/capsule) per day (Ocean Nutrition, Nova Scotia, Canada), providing a total of 5 g of fish oil [1.9–2.2 g eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and 1.1 g docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)] per day. Capsules were provided in sufficient quantity for six weeks. Compliance was assessed from the return of bottles and by measuring plasma phospholipid fatty acid composition. Subjects were asked to report any deviation during the study protocol and to write down their alcohol and fish consumption as well as any side effects.

A validated food-frequency questionnaire (FFQ) was administrated to each participant before the run-in period by a trained registered dietitian (18). This FFQ is based on typical food items available in Quebec and contains 91 items, with 27 items that have between one and three subquestions. The subjects were asked how often they consumed each item per day, per week, per month, or none at all during the last month. Many examples of portion size were provided for a better estimation of the real portion consumed by the subject. Moreover, subjects completed two three-day food records, before and after the n-3 PUFA supplementation period. Dietary data included both foods and beverages consumed at home and outside. A dietitian provided instructions on how to complete the food record with some examples and a written copy of these examples. All foods and beverages consumed on two representative weekdays and one weekend day were weighed or estimated and recorded in food diaries. Dietary intake data were analyzed using Nutrition Data System for Research software version 2011 developed by the Nutrition Coordinating Center (NCC), University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

Anthropometric measurements

Body weight, height, and waist girth were measured according to the procedures recommended by the Airlie Conference (19) and were taken before the run-in period, as well as before and after the n-3 PUFA supplementation. BMI was calculated as weight per meter squared (kg/m2).

Biochemical parameters

The morning after a 12 h overnight fast and 48 h alcohol abstinence, blood samples were collected from an antecubital vein into vacutainer tubes containing EDTA. Blood samples were used to identify individuals with metabolic disorders, who were excluded. Plasma was separated by centrifugation (2,500 g for 10 min at 4°C), and samples were aliquoted and frozen for subsequent analyses. Plasma total cholesterol (total-C) and plasma TG concentrations were measured using enzymatic assays (20, 21). Infranatant (d >1.006 g/ml) with heparin-manganese chloride was used to precipitate VLDL and LDL and then determine HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C) concentrations (22). The equation of Friedewald was used to estimate LDL-cholesterol (LDL-C) concentrations (23). Non-HDL-C was calculated by subtracting HDL-C from total-C. Plasma apoB-100 concentrations were measured by the rocket immunoelectrophoretic method of Laurell, as previously described (24).

Fatty acid composition of plasma phospholipids

Briefly, plasma lipids were extracted with chloroform:methanol (2:1, by volume) according to a modified Folch method (25). Total phospholipids (PL) were separated by thin layer chromatography using a combination of isopropyl ether and acetic acid, and fatty acids of isolated PL were then methylated. Capillary gas chromatography was then used to obtain FA profiles. The technique used for plasma analyses has been previously validated (26).

SNP selection and genotyping

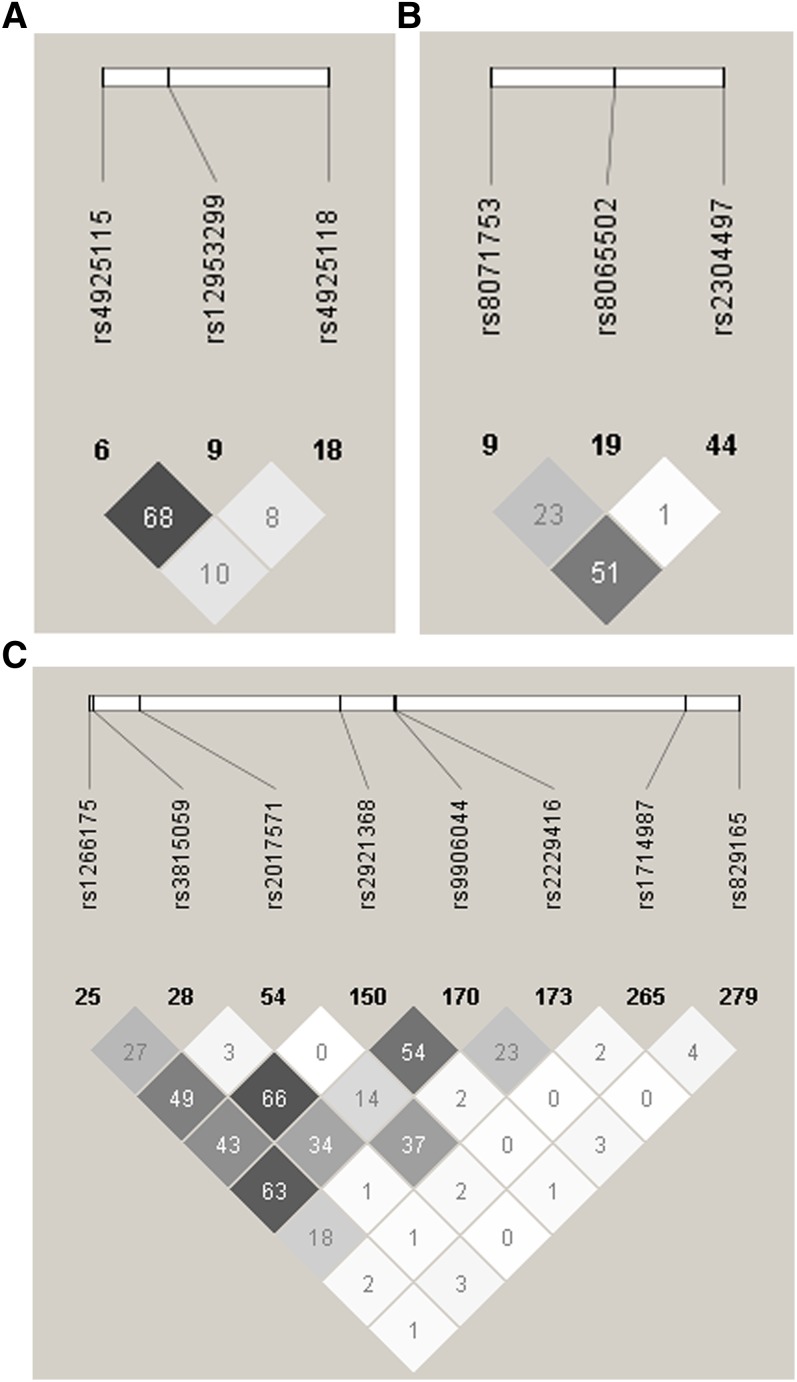

SNPs were selected with the International HapMap Project SNP database [HapMap Data Rel. 28 Phase II+III, August 10, on National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) B36 assembly, dbSNP b126, accessed April 2013]. Tag SNPs (tSNP) were determined with the tagger procedure in HaploView software version 4.2 with minor allele frequency (MAF) > 0.05 and pairwise tagging R2 ≥ 0.80. For each gene, a minimum of 85% of the most common SNPs had to be captured by tSNPs. Additionally, tSNPs were prioritized according to the following criteria i): known SNPs from the literature; ii) SNPs within coding regions (exon); iii) SNPs within the promoter region (2,500 bp before the start codon); iv) SNPs within 3′ untranslated region (UTR) (500 bp after the stop codon); and v) SNPs within 100 bp before an exon-intron splicing boundaries. Afterwards, as shown in Fig. 1, linkage disequilibrium (LD) plots were generated with Haploview software version 4.2. All tSNPs were genotyped within INAF laboratories with the TAQMAN methodology (27), as described previously (8). Briefly, genotypes were determined using ABI Prism SDS version 2.0.5 (Applied Biosystem, Foster City, CA). All SNPs were successfully genotyped. In an attempt to further understand the potential effects of the associated tSNPs on splice consensus sites or on intronic enhancer regions, NNSPLICE (28), Splice Site Finder (29, 30), and FASTSNP (31) web-based programs were used.

Fig. 1.

LD plots of tSNPs in genes involved in the de novo lipogenesis pathway. (A) SREBF1 gene, (B) ACLY gene, and (C) ACACA gene. LD plots were generated by HaploView software version 4.2 using R2 LD values.

Statistical analyses

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was tested with the ALLELE procedure of SAS version 9.3 using Fisher's exact test (P < 0.01). When the genotype frequency for homozygotes individuals of the minor allele was less than 5%, carriers (heterozygotes and homozygotes individuals) of the minor allele were grouped.

Variables nonnormally distributed were logarithmically transformed. To examine the difference between responders and nonresponders for the plasma TG response, two groups were created. The responders group included individuals in which plasma TG concentrations decreased after the supplementation period (relative change in plasma TG < 0%). The nonresponders group included individuals in which plasma TG concentrations did not change or even increased (relative change in plasma TG ≥ 0%). Presupplementation and the relative change in the descriptive characteristics of the participants were compared between the responders and nonresponders with an ANOVA including age, sex, and BMI (except for BMI and waist circumference variables).

To verify the SNPs that were associated with the relative change in plasma TG concentrations, the GLM procedure of SAS was used, with age, sex, and BMI as confounding variables. To take into account the effects of multiple testing, the simpleM procedure described by Gao et al. (32) was utilized. This method takes into consideration the impacts of LD between SNPs and has been demonstrated as efficient and accurate compared with permutation-based corrections (32). First, the composite LD correlation matrix was derived from the data set. Then, eigenvalues were calculated using the SAS PRINCOMP procedure, and the number of effective independent tests was inferred so that the corresponding eigenvalues explain 99.5% of the variation in SNP data, as proposed by Gao et al. (32). The final step applies the Bonferroni correction formula to calculate the adjusted pointwise significance level, which was defined as αG = 0.05 / 9 (effective independent tests). Thus, P-values lower than 5.56 × 10−3 were considered significant.

To identify the variables the most tightly associated with the relative change in plasma TG concentrations, a regression model with stepwise selection, including and retaining only variables and tSNPs with P < 0.05 was created. This regression model included age, sex, BMI, and the tSNPs. Fisher's exact test was performed to verify the differences in the frequencies between responders and nonresponders according to individual SNPs. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS statistical software version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Descriptive characteristics of the study population

Descriptive characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1. Briefly, mean BMI was slightly over 25 kg/m2, and blood lipids were around normal values (33). Descriptive characteristics of the study participants according to plasma TG response (responders versus nonresponders) are shown in Table 2. Before the supplementation, nonresponders had higher HDL-C concentrations and lower plasma TG concentrations than responders. After the supplementation, the BMI of nonresponders increased slightly more than that of responders. Nonresponders had increased total-C and plasma TG concentrations and decreased HDL-C, whereas the opposite was observed for responders. These results are concordant with our previous results for a subset of 12 selected participants from this cohort (34).

TABLE 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the study participants (n = 208)

| Variables | Means ± SD |

| Age (years) | 30.82 ± 8.66 |

| Sex (men/women) | 96/112 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.84 ± 3.73 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | Men: 94.85 ± 10.98 |

| Women: 91.99 ± 10.44 | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 112.03 ± 13.64 (n = 207) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 69.54 ± 9.19 (n = 207) |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/l) | 4.95 ± 0.52 |

| Fasting insulin (pmol/l) | 82.51 ± 35.61 (n = 206) |

| Total-C (mmol/l) | 4.82 ± 1.01 |

| LDL-C (mmol/l) | 2.79 ± 0.87 (n = 207) |

| HDL-C (mmol/l) | 1.46 ± 0.39 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/l) | 1.23 ± 0.64 |

| ApoB (g/l) | 0.86 ± 0.25 (n = 207) |

Values are means ± SD.

TABLE 2.

Descriptive characteristics of the study participants according to plasma TG response (pre- and postsupplementation)

| Presupplementation |

Postsupplementation |

|||||

| Variables | Responders (n = 148) | Non-responders (n = 60) | P a | Responders (n = 148) | Non-responders (n = 60) | P b |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 27.81 ± 3.68 | 27.79 ± 3.91 | 0.98 | Δ0.17 ± 1.53% 27.86 ± 3.79 | Δ0.66 ± 1.46% 27.98 ± 4.01 | 0.03 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | Men (n = 66): 93.98 ± 10.04 | Men (n = 30): 96.70 ± 12.29 | Men: 0.23 | Men (n = 66): Δ0.37 ± 2.17% 94.31 ± 10.08 | Men (n = 30): Δ0.35 ± 1.81% 97.00 ± 12.06 | 0.94 |

| Women (n = 81): 91.74 ± 9.74 | Women (n = 30): 92.52 ± 11.32 | Women: 0.75 | Women (n = 81): Δ-0.09 ± 2.86% 91.63 ± 10.19 | Women (n = 30): Δ0.13 ± 2.21% 92.40 ± 11.41 | 0.98 | |

| Total-C (mmol/l) | 4.74 ± 0.86 | 4.77 ± 1.01 | 0.92 | Δ1.22 ± 10.66% 4.66 ± 0.88 | Δ2.51 ± 10.81% 4.87 ± 1.07 | 0.02 |

| LDL-C (mmol/l) | 2.74 ± 0.77 | 2.79 ± 0.91 | 0.83 | Δ1.61 ± 16.40% 2.76 ± 0.80 | Δ2.27 ± 16.76% 2.84 ± 0.97 | 0.82 |

| HDL-C (mmol/l) | 1.41 ± 0.34 | 1.50 ± 0.39 | 0.03 | Δ4.14 ± 12.76% 1.47 ± 0.40 | Δ1.26 ± 10.28% 1.48 ± 0.41 | 0.005 |

| TG (mmol/l) | 1.28 ± 0.67 | 1.03 ± 0.48 | 0.002 | Δ-24.68 ± 14.98% 0.95 ± 0.50 | Δ19.65 ± 19.36% 1.20 ± 0.54 | <0.0001 |

| ApoB (g/l) | 0.84 ± 0.23 (n = 147) | 0.83 ± 0.26 (n = 59) | 0.66 | Δ3.85 ± 17.31% 0.86 ± 0.23 (n = 147) | Δ7.94 ± 15.61% 0.88 ± 0.25 (n = 58) | 0.12 |

Values are means ± SD.

ANOVA including age, sex, and BMI (except for BMI and waist circumference).

ANOVA assessing the relative change in each variable including age, sex, and BMI (except for BMI and waist circumference).

tSNPs and baseline characteristics according to genotype

The compliance rate for the fish oil supplementation was 94.41 ± 8.33%. The responders had a compliance rate of 93.98 ± 8.85% (n = 148) and for the nonresponders, the compliance rate was 95.48 ± 6.71% (n = 60) (P = 0.17). No differences were observed in fatty acid incorporation into plasma phospholipids (total n-3 PUFA, EPA, and DHA) between responders and nonresponders (data not shown). The selected SNPs are presented in Table 3. All SNPs were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. In Fig. 1, LD plots are presented. Briefly, three tSNPs covered 100% of the known genetic variability within SREBF1 gene, three tSNPs covered 88% for ACLY, and eight tSNPs covered 85% for ACACA.

TABLE 3.

Selected SNPs within SREBF1, ACLY, and ACACA genes

| Gene | dbSNP Number a | Sequence b | Position | MAF | Genotype Frequency | ||

| SREBF1 | rs4925115 | GGTGGGC[A/G]GGGCAGA | Intron | 0.425 | G/G (n = 66) | A/G (n = 107) | A/A (n = 35) |

| 0.317 | 0.514 | 0.168 | |||||

| rs4925118 | GTCGGTT[C/T]GCGTCCT | Intron | 0.185 | C/C (n = 140) | C/T (n = 59) | T/T (n = 9) | |

| 0.673 | 0.284 | 0.043 | |||||

| rs12953299 | GCAGGGG[A/G]CACTAAT | Intron | 0.481 | G/G (n = 56) | A/G (n = 104) | A/A (n = 48) | |

| 0.269 | 0.500 | 0.231 | |||||

| ACLY | rs8071753 | ACTACCA[A/G]TCCAAGT | Intron | 0.214 | G/G (n = 127) | A/G (n = 73) | A/A (n = 8) |

| 0.611 | 0.351 | 0.039 | |||||

| rs8065502 | CCTCCGG[A/G]TGCTTCC | Exon (synonymous [His] → [His]) | 0.075 | G/G (n = 178) | A/G (n = 29) | A/A (n = 1) | |

| 0.856 | 0.139 | 0.005 | |||||

| rs2304497 | TCTTGTC[G/T]TCAGGGG | Exon (missense [Glu] → [Asp]) | 0.091 | T/T (n = 174) | G/T (n = 30) | G/G (n = 4) | |

| 0.837 | 0.144 | 0.019 | |||||

| ACACA | rs2017571 | CCTTCTC[C/T]TCCTCTT | Intron | 0.202 | T/T (n = 133) | C/T (n = 66) | C/C (n = 9) |

| 0.639 | 0.317 | 0.043 | |||||

| rs2921368 | TTACAGA[C/G]CTACTGG | Intron | 0.202 | C/C (n = 131) | C/G (n = 70) | G/G (n = 7) | |

| 0.630 | 0.337 | 0.034 | |||||

| rs9906044 | CAGAATA[A/T]CTACTGC | Intron | 0.349 | A/A (n = 87) | A/T (n = 97) | T/T (n = 24) | |

| 0.418 | 0.466 | 0.115 | |||||

| rs2229416 | GCTTTCA[A/C/G]ATGAACA | Exon (synonymous [Gln] → [Gln]) | 0.137 | C/C (n = 155) | C/T (n = 49) | T/T (n = 4) | |

| 0.745 | 0.236 | 0.019 | |||||

| rs1714987 | CCCACCA[C/G]TGCCCCT | Intron | 0.180 | C/C (n = 139) | C/G (n = 63) | G/G (n = 6) | |

| 0.668 | 0.303 | 0.029 | |||||

| rs1266175 | GAACACC[A/G]CCTGGGT | Intron | 0.389 | A/A (n = 78) | A/G (n = 98) | G/G (n = 32) | |

| 0.375 | 0.471 | 0.154 | |||||

| rs3815059 | GAAATCA[A/T]GAAATTT | Intron | 0.178 | A/A (n = 140) | A/T (n = 62) | T/T (n = 6) | |

| 0.673 | 0.298 | 0.029 | |||||

| rs829165 | AATTTGG[C/T]GATTGTT | Intron near 5′UTR region | 0.123 | C/C (n = 162) | C/T (n = 41) | T/T (n = 5) | |

| 0.779 | 0.197 | 0.024 | |||||

SNP reference Id from dbSNP Short Genetic Variations NCBI Reference Assembly.

Gene sequence from dbSNP Short Genetic Variations NCBI Reference Assembly.

Age, sex, and baseline BMI did not differ by genotypes except for rs4925118 (SREBF1) for age, and rs12953299 (SREBF1) and rs1266175 (ACACA) for sex (P = 0.01, P = 0.01, and P = 0.02, respectively). C/C homozygotes of rs4925118 (SREBF1) were slightly older than carriers of the rare allele (data not shown). A greater proportion of men were A/A homozygotes for rs12953299 (SREBF1) and G/G homozygotes for rs1266175 (63% for both). Genotype frequencies according to the plasma TG response group seemed to differ only for rs8071753 (ACLY) (P = 0.02), and trends were observed for three tSNPs within ACACA gene (rs2921368, rs1714987, and rs3815059) (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Frequencies of genotypes according to plasma TG response group

| Gene | SNP | Responder | Nonresponder | P a |

| ACLY | rs8071753 | A/A + A/G n = 50 (34%) | A/A + A/G n = 31 (52%) | 0.02 |

| G/G n = 98 (66%) | G/G n = 29 (48%) | |||

| ACACA | rs2921368 | C/G + G/G n = 61 (41%) | C/G + G/G n = 16 (27%) | 0.06 |

| C/C n = 87 (59%) | C/C n = 44 (73%) | |||

| rs1714987 | C/G + G/G n = 55 (37%) | C/G + G/G n = 14 (23%) | 0.07 | |

| C/C n = 93 (63%) | C/C n = 46 (77%) | |||

| rs3815059 | A/T + T/T n = 54 (36%) | A/T + T/T n = 14 (23%) | 0.07 | |

| A/A n = 94 (64%) | A/A n = 46 (77%) |

P values from Fisher's exact test.

Associations between tSNPs and baseline plasma TG levels

The SNP rs1714987 (ACACA) seemed associated with presupplementation plasma TG concentrations (P = 0.006) (adjusted for age, sex, and BMI). Carriers of the G allele (n = 69) seemed to have higher baseline plasma TG concentrations than C/C homozygotes (n = 139) (1.32 ± 0.58 mmol/l compared with 1.15 ± 0.65 mmol/l).

Association between tSNPs and the plasma TG relative change

As presented in Table 5, two SNPs [rs8071753 (ACLY) and rs1714987 (ACACA)] were associated with the relative change in plasma TG concentrations (adjusted for age, sex, and BMI). Both associated tSNPs (rs8071753 and rs1714987) where located within intronic regions. To further examine the putative effects of these tSNPs on splice site, NNSPLICE, Splice Site Finder, and FASTSNP were used. According to Splice Site Finder, A allele of rs8071753 seems to slightly decrease a putative donor site (72.61–74.59) compared with G allele. C allele of rs1714987 also slightly decreased a putative donor site compared with G allele (81.66–83.42). None of these predictions were confirmed by NNSPLICE program. According to FASTSNP program, rs8071753 and rs1714987 were not predicted to be in any transcription factor binding site or splicing site. Hence, it is unlikely that these SNPs might be responsible for possible alternative splice events or have a functional impact.

TABLE 5.

Impact of SNPs on plasma TG response after intake of fish oil

| Gene | SNP | Genotype | % Change in TG | P a |

| ACLY | rs8071753 | A/A+A/G (n = 81) | −5.64 ± 28.85 | 0.004 |

| G/G (n = 127) | −15.87 ± 23.10 | |||

| ACACA | rs1714987 | G/G+C/G (n = 69) | −18.91 ± 21.38 | 0.005 |

| C/C (n = 139) | −8.40 ± 27.29 | |||

| ACLY | rs8065502 | A/A+A/G (n = 30) | −2.27 ± 32.10 | 0.02 |

| G/G (n = 178) | −13.51 ± 24.46 | |||

| ACACA | rs2017571 | C/C+C/T (n = 75) | −7.23 ± 27.12 | 0.04 |

| T/T (n = 133) | −14.52 ± 24.92 | |||

| ACACA | rs3815059 | T/T+A/T (n = 68) | −16.31 ± 23.36 | 0.08 |

| A/A (n = 140) | −9.74 ± 26.88 | |||

| SREBF1 | rs4925118 | T/T+C/T (n = 68) | −7.25 ± 27.02 | 0.08 |

| C/C (n = 140) | −14.14 ± 25.15 | |||

| ACACA | rs2229416 | T/T+C/T (n = 53) | −7.73 ± 28.14 | 0.20 |

| C/C (n = 155) | −13.21 ± 25.04 | |||

| ACACA | rs2921368 | G/G+C/G (n = 77) | −14.86 ± 22.31 | 0.23 |

| C/C (n = 131) | −10.14 ± 27.74 | |||

| ACLY | rs2304497 | G/G+G/T (n = 34) | −8.12 ± 25.44 | 0.36 |

| T/T (n = 174) | −12.63 ± 26.01 | |||

| SREBF1 | rs12953299 | A/A (n = 48) | −8.09 ± 27.30 | 0.40 |

| A/G (n = 104) | −14.42 ± 25.32 | |||

| G/G (n = 56) | −10.44 ± 25.75 | |||

| ACACA | rs829165 | T/T+C/T (n = 46) | −14.53 ± 29.17 | 0.47 |

| C/C (n = 162) | −11.14 ± 24.96 | |||

| SREBF1 | rs4925115 | A/A (n = 35) | −7.24 ± 25.18 | 0.57 |

| A/G (n = 107) | −12.84 ± 26.47 | |||

| G/G (n = 66) | −12.82 ± 25.49 | |||

| ACACA | rs9906044 | T/T (n = 24) | −10.10 ± 26.38 | 0.82 |

| A/T (n = 97) | −13.28 ± 23.54 | |||

| A/A (n = 87) | −10.83 ± 28.41 | |||

| ACACA | rs1266175 | G/G (n = 32) | −9.61 ± 26.75 | 0.90 |

| A/G (n = 98) | −12.52 ± 25.30 | |||

| A/A (n = 78) | −12.04 ± 26.61 |

Values are means ± SD.

P values of the GLM models are adjusted for age, sex, and BMI. P values in bold were considered significant (<5.56 × 10−3).

In an attempt to identify the variable the most tightly associated with the relative change in plasma TG concentrations, a regression model with stepwise selection including age, sex, BMI, and the tSNPs was computed. Only the tSNPs rs8071753 (partial R2 = 3.73%, P = 0.005) and rs1714987 (partial R2 = 4.01%, P = 0.003) contributed to the model. In sum, the two SNPs allowed explaining 7.73% of the variance in the relative change of plasma TG concentrations. Age, sex, and BMI were not contributors to the regression model, indicating that they were not associated with the relative change in plasma TG concentrations following the n-3 PUFA supplementation.

The mean plasma TG relative change of individuals with both genotypes (A/A or A/G for rs8071753 and C/C for rs1714987) associated with a lower plasma TG response was −0.63 ± 30.54% (n = 52) compared with a mean of −15.64 ± 23.09% (n = 156) for the individuals with zero or one genotype (P = 0.0001).

DISCUSSION

According to the present results, certain SNPs within genes involved in de novo lipogenesis may explain part of the differences observed in plasma TG concentrations following n-3 PUFA supplementation. The impact of n-3 PUFA on plasma TG concentrations may be modified by SNPs within genes involved in the de novo lipogenesis pathway. SNPs may lead to an increase or a decrease in the activity of the enzymes or to the affinity to certain transcription factors affecting the fatty acid metabolic pathway. In this study, two SNPs (rs8071753 and rs1714987) within genes involved in de novo lipogenesis were associated with the plasma TG response following n-3 PUFA supplementation. This biological pathway contributes directly for only small amounts (<5%) to the NEFA pool utilized for the assembly of VLDL-TG among healthy individuals (35). However, among individuals with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease or with hypertriglyceridemia, it may contribute more importantly (around 15%) to the fatty acids used for VLDL-TG production (35–37). Thus, it is possible that among individuals with a more deteriorated metabolic profile, SNPs within genes related to de novo lipogenesis may have been more strongly associated with plasma TG response. It has been observed that NEFA derived from de novo lipogenesis are preferentially incorporated into the hepatic intracellular storage pool as TG (38). Intracellular TG can then be mobilized in the cytosol by lipolysis, followed by reesterification through a delayed pathway, also contributing to VLDL-TG production (38, 39).

As described earlier, n-3 PUFA consumption induces a decrease in de novo lipogenesis mediated by SREBF1 gene (9–11, 40). In the literature, two SNPs within SREBF1 gene (rs2297508 and rs1889018) have been associated with a modest increase of type 2 diabetes risk, body weight (BMI or obesity), total-C, LDL-C, and plasma TG concentrations (14, 16, 41, 42). SREBF1 regulates the activity of both ACLY and ACACA genes. ACLY gene encodes for the enzyme converting citrate from the Krebs cycle to acetyl-CoA that enters the first step of de novo lipogenesis. The enzyme ACACA then produces malonyl-CoA from acetyl-CoA (12, 13). We hypothesized that SNPs within these genes may modify the affinity of sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP1) with the sterol regulatory element (SRE) within the promoter region or their function (43). This study is the first to report an association between rs8071753 within ACLY gene and plasma TG response following n-3 PUFA supplementation. This SNP is located within an intronic region of ACLY gene and does not seem to have any regulatory impact on ACLY gene (44). In ACACA gene, the SNP rs1714987 was also associated with the plasma TG response. Interestingly, carriers of the minor G allele seemed to have higher baseline plasma TG concentrations, and their plasma TG concentrations decreased by almost twice as much as C/C homozygotes following n-3 PUFA supplementation. Thus, rs1714987 seems to have a beneficial impact on the plasma TG response following the intake of n-3 PUFA. Diaz et al. (17), have observed associations between SNPs within ACACA gene (rs1266175 and rs2229416) and plasma TG concentrations following the intake of certain antipsychotic drugs that increase the risk of hyperlipidemia. Globally, these drugs have the opposite effect of n-3 PUFA on lipid metabolism by increasing lipogenesis and decreasing fatty acid oxidation (45, 46).

When the two SNPs associated with the relative change in plasma TG concentrations were grouped, results demonstrate that individuals having both “at risk” genotypes have hardly diminished their plasma TG concentration despite the intake of fish oil. It is likely that individuals who carry different combinations of SNPs may be at an increased risk of no change or even an increase of their plasma TG concentrations following n-3 PUFA supplementation. However, these results need to be replicated and regression models including more SNPs are required in order to eventually generate a proper model leading to a clear identification of individuals who will have a beneficial plasma TG response following n-3 PUFA supplementation. In this study, baseline plasma TG concentrations were within normal values; it is possible that with higher baseline values, there would have been fewer individuals considered as “nonresponders” following the intake of fish oil.

Overall, this study shows that SNPs within genes involved in de novo lipogenesis may have an impact on the plasma TG response following the intake of fish oil. These SNPs may affect gene regulation by unknown mechanisms or are potentially in LD with other causal SNPs. More SNPs within genes involved in de novo lipogenesis and also in other metabolic pathways, such as fatty acid β-oxidation, should be studied to further understand the genetic basis behind the observed variability in plasma TG response after fish oil consumption. The determination of SNPs associated with the plasma TG response after the intake of fish oil could help in the future to use fish oil more efficiently among hypertriglyceridemic individuals.

Acknowledgments

This research would not have been possible without the excellent collaboration of the participants. The authors thank Hubert Cormier, Véronique Garneau, Alain Houde, Catherine Ouellette, Catherine Raymond, and Élisabeth Thifault, and the nurses, Danielle Aubin and Steeve Larouche, for their participation in the recruitment of participants, study coordination, and data collection.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- ACACA

- acetyl-CoA carboxylase alpha

- ACLY

- ATP citrate lyase

- BMI

- body mass index

- CHD

- coronary heart disease

- CVD

- cardiovascular disease

- DHA

- docosahexaenoic acid

- EPA

- eicosapentaenoic acid

- FFQ

- food-frequency questionnaire

- HDL-C

- HDL-cholesterol

- LD

- linkage disequilibrium

- LDL-C

- LDL-cholesterol

- MAF

- minor allele frequency

- NCBI

- National Center for Biotechnology Information

- NCC

- Nutrition Coordinating Center PL, phospholipid

- RUNX1

- runt-related transcription factor 1

- SNP

- single-nucleotide polymorphism

- SRE

- sterol regulatory element

- SREBF1

- sterol regulatory element-binding transcription factor 1

- tSNP

- tagSNP

- TG

- triglyceride

- total-C

- total-cholesterol

- UTR

- untranslated region

This work was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Grant MOP229488, Fonds de recherche en santé du Quebec (FRQS) (A.B.M.), CIHR Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarships Doctoral Awards 201210GSD-304012-190387 (A.B.M.), CIHR Bisby Postdoctoral Fellowship Award 200810BFE (I.R.), and Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Genomics Applied to Nutrition and Health (M.C.V.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Statistics Canada Leading Causes of Death in Canada. 2009. Accessed November 23, 2012. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/84–215-x/2012001/hl-fs-eng.htm

- 2.Morrison A., Hokanson J. E. 2009. The independent relationship between triglycerides and coronary heart disease. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 5: 89–95 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ninomiya J. K., L'Italien G., Criqui M. H., Whyte J. L., Gamst A., Chen R. S. 2004. Association of the metabolic syndrome with history of myocardial infarction and stroke in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Circulation. 109: 42–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Angelantonio A. E., Sarwar N., Perry P., Kaptoge S., Ray K. K., Thompson A., Wood A. M., Lewington S., Sattar N., Packard C. J., et al. 2009. Major lipids, apolipoproteins, and risk of vascular disease. JAMA. 302: 1993–2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh A., Schwartzbard A., Gianos E., Berger J. S., Weintraub H. 2013. What should we do about hypertriglyceridemia in coronary artery disease patients? Curr. Treat. Options Cardiovasc. Med. 15: 104–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Madden J., Williams C. M., Calder P. C., Lietz G., Miles E. A., Cordell H., Mathers J. C., Minihane A. M. 2011. The impact of common gene variants on the response of biomarkers of cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk to increased fish oil fatty acids intakes. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 31: 203–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caslake M. J., Miles E. A., Kofler B. M., Lietz G., Curtis P., Armah C. K., Kimber A. C., Grew J. P., Farrell L., Stannard J., et al. 2008. Effect of sex and genotype on cardiovascular biomarker response to fish oils: the FINGEN Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 88: 618–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cormier H., Rudkowska I., Paradis A. M., Thifault E., Garneau V., Lemieux S., Couture P., Vohl M. C. 2012. Association between polymorphisms in the fatty acid desaturase gene cluster and the plasma triacylglycerol response to an n-3 PUFA supplementation. Nutrients. 4: 1026–1041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eberle D., Hegarty B., Bossard P., Ferre P., Foufelle F. 2004. SREBP transcription factors: master regulators of lipid homeostasis. Biochimie. 86: 839–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu J., Teran-Garcia M., Park J. H., Nakamura M. T., Clarke S. D. 2001. Polyunsaturated fatty acids suppress hepatic sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1 expression by accelerating transcript decay. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 9800–9807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanaka N., Zhang X., Sugiyama E., Kono H., Horiuchi A., Nakajima T., Kanbe H., Tanaka E., Gonzalez F. J., Aoyama T. 2010. Eicosapentaenoic acid improves hepatic steatosis independent of PPARalpha activation through inhibition of SREBP-1 maturation in mice. Biochem. Pharmacol. 80: 1601–1612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chypre M., Zaidi N., Smans K. 2012. ATP-citrate lyase: a mini-review. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 422: 1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wakil S. J., Stoops J. K., Joshi V. C. 1983. Fatty acid synthesis and its regulation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 52: 537–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eberle D., Clement K., Meyre D., Sahbatou M., Vaxillaire M., Le G. A., Ferre P., Basdevant A., Froguel P., Foufelle F. 2004. SREBF-1 gene polymorphisms are associated with obesity and type 2 diabetes in French obese and diabetic cohorts. Diabetes. 53: 2153–2157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Z., Gong R. R., Du J., Xiao L. Y., Duan W., Zhou X. D., Fang D. Z. 2011. Associations of the SREBP-1c gene polymorphism with gender-specific changes in serum lipids induced by a high-carbohydrate diet in healthy Chinese youth. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 36: 226–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grarup N., Stender-Petersen K. L., Andersson E. A., Jorgensen T., Borch-Johnsen K., Sandbaek A., Lauritzen T., Schmitz O., Hansen T., Pedersen O. 2008. Association of variants in the sterol regulatory element-binding factor 1 (SREBF1) gene with type 2 diabetes, glycemia, and insulin resistance: a study of 15,734 Danish subjects. Diabetes. 57: 1136–1142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diaz F. J., Meary A., Arranz M. J., Ruano G., Windemuth A., de. Leon J. 2009. Acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase alpha gene variations may be associated with the direct effects of some antipsychotics on triglyceride levels. Schizophr. Res. 115: 136–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goulet J., Nadeau G., Lapointe A., Lamarche B., Lemieux S. 2004. Validity and reproducibility of an interviewer-administered food frequency questionnaire for healthy French-Canadian men and women. Nutr. J. 3: 13–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Callaway C. W., Chumlea W. C., Bouchard C., Himes J. H., Lohman T. G., Martin A. D., Mitchell C. D., Mueller W. H., Roche A. F., Seefeldt V. D. 1988. Standardization of anthropometric measurements. In The Airlie (VA) Consensus Conference. T. Lohman, A. Roche, and R. Martorel, editors. Human Kinetics Publishers, Champaign, IL. 39–80. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McNamara J. R., Schaefer E. J. 1987. Automated enzymatic standardized lipid analyses for plasma and lipoprotein fractions. Clin. Chim. Acta. 166: 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burstein M., Samaille J. 1960. On a rapid determination of the cholesterol bound to the serum alpha- and beta-lipoproteins. Clin. Chim. Acta. 5: 609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Albers J. J., Warnick G. R., Wiebe D., King P., Steiner P., Smith L., Breckenridge C., Chow A., Kuba K., Weidman S., et al. 1978. Multi-laboratory comparison of three heparin-Mn2+ precipitation procedures for estimating cholesterol in high-density lipoprotein. Clin. Chem. 24: 853–856 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedewald W. T., Levy R. I., Fredrickson D. S. 1972. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin. Chem. 18: 499–502 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laurell C. B. 1966. Quantitative estimation of proteins by electrophoresis in agarose gel containing antibodies. Anal. Biochem. 15: 45–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaikh N. A., Downar E. 1981. Time course of changes in porcine myocardial phospholipid levels during ischemia. A reassessment of the lysolipid hypothesis. Circ. Res. 49: 316–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kroger E., Verreault R., Carmichael P. H., Lindsay J., Julien P., Dewailly E., Ayotte P., Laurin D. 2009. Omega-3 fatty acids and risk of dementia: the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 90: 184–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Livak K. J. 1999. Allelic discrimination using fluorogenic probes and the 5′ nuclease assay. Genet. Anal. 14: 143–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reese M. G., Eeckman F. H., Kulp D., Haussler D. 1997. Improved splice site detection in Genie. J. Comput. Biol. 4: 311–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shapiro M. B., Senapathy P. 1987. RNA splice junctions of different classes of eukaryotes: sequence statistics and functional implications in gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 15: 7155–7174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Desmet F. O., Hamroun D., Lalande M., Collod-Beroud G., Claustres M., Beroud C. 2009. Human Splicing Finder: an online bioinformatics tool to predict splicing signals. Nucleic Acids Res. 37: e67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yuan H. Y., Chiou J. J., Tseng W. H., Liu C. H., Liu C. K., Lin Y. J., Wang H. H., Yao A., Chen Y. T., Hsu C. N. 2006. FASTSNP: an always up-to-date and extendable service for SNP function analysis and prioritization. Nucleic Acids Res. 34: W635–W641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gao X., Starmer J., Martin E. R. 2008. A multiple testing correction method for genetic association studies using correlated single nucleotide polymorphisms. Genet. Epidemiol. 32: 361–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel 2002. Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 106: 3143–3421 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rudkowska I., Paradis A. M., Thifault E., Julien P., Barbier O., Couture P., Lemieux S., Vohl M. C. 2012. Differences in metabolomic and transcriptomic profiles between responders and non-responders to an n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) supplementation. Genes Nutr. 8: 411–423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fabbrini E., Mohammed B. S., Magkos F., Korenblat K. M., Patterson B. W., Klein S. 2008. Alterations in adipose tissue and hepatic lipid kinetics in obese men and women with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 134: 424–431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diraison F., Moulin P., Beylot M. 2003. Contribution of hepatic de novo lipogenesis and reesterification of plasma non esterified fatty acids to plasma triglyceride synthesis during non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Diabetes Metab. 29: 478–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vedala A., Wang W., Neese R. A., Christiansen M. P., Hellerstein M. K. 2006. Delayed secretory pathway contributions to VLDL-triglycerides from plasma NEFA, diet, and de novo lipogenesis in humans. J. Lipid Res. 47: 2562–2574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gibbons G. F., Bartlett S. M., Sparks C. E., Sparks J. D. 1992. Extracellular fatty acids are not utilized directly for the synthesis of very-low-density lipoprotein in primary cultures of rat hepatocytes. Biochem. J. 287: 749–753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gibbons G. F., Wiggins D., Brown A. M., Hebbachi A. M. 2004. Synthesis and function of hepatic very-low-density lipoprotein. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 32: 59–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jump D. B. 2008. N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid regulation of hepatic gene transcription. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 19: 242–247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laudes M., Barroso I., Luan J., Soos M. A., Yeo G., Meirhaeghe A., Logie L., Vidal-Puig A., Schafer A. J., Wareham N. J., et al. 2004. Genetic variants in human sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c in syndromes of severe insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 53: 842–846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu J. X., Liu J., Li P. Q., Xie X. D., Guo Q., Tian L. M., Ma X. Q., Zhang J. P., Liu J., Gao J. Y. 2008. Association of sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c gene polymorphism with type 2 diabetes mellitus, insulin resistance and blood lipid levels in Chinese population. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 82: 42–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yin H. Q., Kim M., Kim J. H., Kong G., Kang K. S., Kim H. L., Yoon B. I., Lee M. O., Lee B. H. 2007. Differential gene expression and lipid metabolism in fatty liver induced by acute ethanol treatment in mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 223: 225–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.NCBI dbSNP Short Genetic Variations. 2012. Accessed December 11, 2012. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/snp_ref.cgi?rs=1293329

- 45.de Leon J., Correa J. C., Ruano G., Windemuth A., Arranz M. J., Diaz F. J. 2008. Exploring genetic variations that may be associated with the direct effects of some antipsychotics on lipid levels. Schizophr. Res. 98: 40–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harris W. S., Bulchandani D. 2006. Why do omega-3 fatty acids lower serum triglycerides? Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 17: 387–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]