Abstract

Background

Acute flail mitral valve frequently results in severe mitral regurgitation. However, its clinical presentation can be similar to other disease processes, potentially leading to initial misdiagnosis and a morbid outcome. We sought to analyze baseline characteristics, clinical presentations, time to diagnosis, and in-hospital mortalities of patients with the acute flail mitral valve.

Methods

Two hundred and sixty two consecutive echocardiograms with severe mitral regurgitation performed between February 2005 and October 2010 at the Jack D. Weiler Hospital (Bronx, New York, USA) were reviewed. Adult patients who had presented with new onset flail mitral valves were selected for this retrospective study.

Results

Fifteen patients were found to have acute flail mitral valve. The majority was elderly male. Over half presented to the emergency room with a sudden onset of dyspnea. A mitral regurgitant murmur was appreciated in only a third of the patients. The chest X-ray of five patients had no acute pulmonary findings, whereas, two were found to have gross unilateral pulmonary edema. Clinically, 60% were misdiagnosed on admission. Using echocardiogram, the correct diagnosis of flail mitral valve was made in all cases, however, only 40% on the day of presentation. The maximum time to echocardiographic diagnosis was 4 days. The main cause of acute flail mitral valve was degenerative disease. Seven patients were managed surgically. Overall, there was only one mortality (7%) during incident hospitalization.

Conclusions

Initial misdiagnosis of acute flail mitral valve happens frequently. Early echocardiographic exam is essential in the timely diagnosis and management of acute flail mitral valve.

Keywords: Acute flail mitral valve, Echocardiography, Misdiagnosis, Severe mitral valve regurgitation

1. Introduction

The mitral valve apparatus consists of leaflets, annulus, chordae tendineae, papillary muscles and subjacent myocardium.1 An abnormality or disease that affects any of the aforementioned components and results in ruptured chordae tendineae can cause a flail mitral valve.2 Acute flail mitral valve can occur in patients with degeneration of the mitral valve apparatus, during the course of infective endocarditis, or in the setting of acute myocardial infarction (MI) with papillary muscle rupture.1,3 These patients present with a variety of clinical manifestations ranging from sudden onset dyspnea to fever, cough, and chest pain.1,4 These non-specific clinical presentations may be mistaken for multiple other conditions, including acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), pulmonary embolism, and pneumonia. Appropriate therapy may thus be delayed and result in high morbidity and mortality. In our study, we analyzed baseline characteristics, clinical presentations, time to diagnosis based on echocardiographic imaging, and in-hospital mortalities of patients with an acute flail mitral valve at the university based community hospital in New York city.

2. Materials and methods

Two hundred and sixty two consecutive transthoracic echocardiograms (TTE) and transesophageal echocardiograms (TEE) with severe mitral regurgitation, performed from February 2005 to October 2010 at Jack D. Weiler Hospital (Bronx, New York, USA), were analyzed retrospectively. Adult patients (age >21 years) presenting with new onset flail mitral valve confirmed by echocardiogram were selected for this study. Patients with the chronic flail mitral valve defined as having a prior echocardiogram showing a flail mitral valve leaflets were excluded.

Clinical records including prior medical history, incident clinical presentations, physical examination, laboratory tests, chest X-ray (CXR), electrocardiogram, echocardiogram, cardiac catheterization, management during hospitalization, as well as in-hospital mortalities, were reviewed. The initial diagnoses made on admission according to the International Classification of Disease, 9th revision, clinical modification coding systems were used as admitting diagnoses. Flail mitral valve was diagnosed when the leaflet tip of mitral valve moved rapidly into the left atrium during systole on echocardiogram.4,5

In our study, degenerative mitral valve disease denoted a variety of structural lesions that were secondary to myxoid infiltration or fibroelastic deficiency. The diagnosis was made if clinical history was suggestive and echocardiography showed elongated and redundant billowing leaflets, bulky and thickened leaflets, displacement of the insertion of the posterior leaflet creating an out-pouching at the leaflet base, severe annular dilation, annular or subannular calcification, or a single, thin, prolapsing segment, sometimes with a visible ruptured chord.6 Diagnosis of infective mitral valve endocarditis was based on classic echocardiographic features such as heterogenous, mobile, echodense masses attached to valvular leaflets or periannular abscesses in addition to typical clinical manifestations such as fever, leukocytosis and persistent bacteremia.7

Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation. Qualitative variables were presented as absolute values and percentages because of the small sample size.

3. Results

Overall, 262 patients with severe mitral regurgitation on a resting TTE or TEE were screened for flail mitral valve. Fifteen were found to have acute flail mitral valve [Fig. 1]. Their baseline characteristics are found in Table 1. The majority was old male patients with multiple comorbidities.

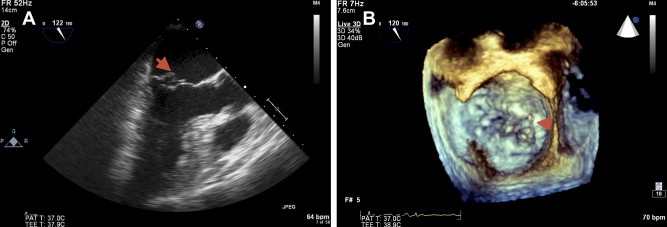

Fig. 1.

Echocardiogram (A: Mid-esophageal view of transesophageal echocardiogram; B: En face surgeon view of 3-dimensional echocardiogram) in a patient with flail mitral valve leaflet shows ruptured mitral chordae tendineae. Arrows point to the flail mitral valve leaflet (A) and ruptured mitral chordae tendineae (B).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients presenting with acute flail mitral valve.

| Patient number | 15 |

| Age (year) | 69 ± 21 |

| Gender (%) | |

| Female | 2 (13) |

| Male | 13 (87) |

| Comorbidities (%) | |

| Hypertension | 9 (60) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 3 (20) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3 (20) |

| Coronary artery disease | 4 (27) |

| Congestive heart failure | 3 (20) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 3 (20) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 3 (20) |

On presentation to the emergency room, over half of the patients complained of new onset of dyspnea [Table 2]. Only a third had a holosystolic murmur consistent with mitral regurgitation on physical examination [Table 2]. A third of the patients presented with normal CXR [Table 2]. Interestingly, there was no other predominant presenting symptoms, physical or CXR findings in our patient population.

Table 2.

Clinical presentations of acute flail mitral valve (n = 15).

| Presenting symptoms (%) | |

| Dyspnea | 8 (53) |

| Chest pain | 3 (20) |

| Fever | 3 (20) |

| Cough | 1 (7) |

| Physical examination (%) | |

| Murmur | 5 (33) |

| Chest X-ray (%) | |

| No acute pulmonary findings | 5 (33) |

| Pulmonary vascular congestion | 2 (13) |

| Bilateral pleural effusion | 3 (20) |

| Unilateral pleural edema | 2 (13) |

| Pneumonia | 3 (20) |

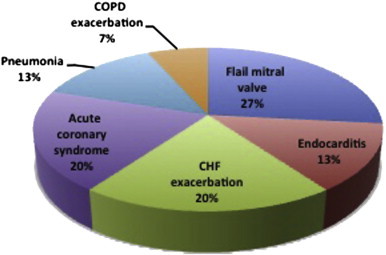

The initial diagnosis included four (27%) for flail mitral valve, two (13%) for presumed endocarditis, three (20%) for CHF exacerbation, three (20%) for acute coronary syndrome (ACS), two (13%) for pneumonia, and one (7%) for COPD exacerbation [Fig. 2]. Overall, only six of the 15 patients (40%) were initially admitted with correct diagnoses. The patients with presumed ACS were taken to cardiac catheterization laboratory and found to have either normal or non-critical coronary artery disease. Instead, severe mitral regurgitation was detected by cardiac ventriculography, and flail mitral valve was later confirmed by TEE. The overwhelming majority of acute flail mitral valve was secondary to degenerative diseases in our study population [Table 3]. The remaining patients were secondary to infective endocarditis. There was no acute flail mitral valve from ischemic papillary muscle in our series.

Fig. 2.

Diagnoses made on admission in patients with flail mitral valve.

Table 3.

Follow-up acute flail mitral valve (n = 15).

| Duration to reach correct diagnosis (%) | |

| 0 day | 6 (40) |

| 1 day | 5 (33) |

| 2 days | 1 (7) |

| 3 days | 2 (13) |

| 4 days | 1 (7) |

| Causes (%) | |

| Degenerative mitral valve diseases | 13 (87) |

| Endocarditis | 2 (13) |

| Ischemic papillary muscle rupture | 0 (0) |

| Management (%) | |

| Medical | 8 (53) |

| Surgical | 7 (47) |

| Mitral valve repair | 3 (43) |

| Mitral valve replacement | 4 (57) |

| Incident in-hospital mortality (%) | |

| Medical management | 1 (7) |

| Surgical correction | 0 (0) |

Almost half of patients underwent mitral valve surgery with cardiac catheterization preceding surgery in all cases. In total, nine patients (60%) underwent TEE to better characterize the mitral valve. Six of the seven surgical patients had a TEE except one patient whose flail mitral valve was well visualized by TTE. Of the surgical patients, four had mitral valve replacement and three had mitral valve repair [Table 3]. Two were found to have severe CAD that required coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) in addition to the mitral valve surgery.

The remaining eight patients were medically managed [Table 3]. The only in-hospital mortality was a 90-year-old female who presented with sudden onset dyspnea, unilateral pulmonary edema on CXR [Fig. 3], and initial misdiagnosis of pneumonia.

Fig. 3.

Portable chest X-ray shows pulmonary vascular congestion and right-sided unilateral pleural effusion.

In our hospital, the correct diagnosis of acute flail mitral valve via echocardiogram was established in all cases [Table 3]. Approximately, three quarters had a TTE diagnosis within 24 h. Only six patients were identified promptly by TTE in the emergency room, resulting in direct admissions to the surgical service for planned corrective surgery. All patients were correctly diagnosed within 4 days of presentation to the emergency room.

4. Discussion

Acute flail mitral valve often leads to severe mitral regurgitation.1 However, a wide spectrum of physical complaints may present significant challenges to clinicians in early recognition, and hence lead to increased morbidity and mortality.

Clinical history and physical examination may help in making the correct diagnosis. However, our data showed that only half of patients presented with a sudden onset of dyspnea, a hallmark symptom of acute flail mitral valve, and a mitral regurgitant murmur was only detected in a third of our cohort. Consistent with prior findings,4,8 our study suggests that the sensitivity of the history and physical examination in detecting acute flail mitral valve is fairly low.

CXR may not always be helpful in diagnosing acute flail mitral valve as it may not show acute pulmonary findings as seen predominantly in our study, even though bilateral pulmonary venous congestion, interstitial edema, and symmetrical bilateral pleural effusion are often noted.4 Unilateral pulmonary edema, an independent risk marker of mortality,9 occurs when the mitral regurgitant jet is directed predominantly to the orifice of an upper lobe pulmonary vein.1 As presented in our study, it may lead to a false diagnosis of pneumonia, delayed management and resultant death of the patient if not being promptly recognized by the physician.

Therefore, echocardiography remains the key modality in the diagnosis of acute flail mitral valve.6–8 In our hospital, all patients who received an echocardiogram in the emergency room have a correct admitting diagnosis and proper management. Delayed recognition and initial misdiagnosis often results in morbid outcomes. In order to reduce the associated morbidity and mortality, it is essential to raise awareness of this clinical entity and use echocardiography appropriately as the main reason of delay in obtaining an echocardiogram is the lack of awareness of a cardiac etiology of the clinical presentation.

As per the 2001 appropriate use criteria for echocardiography,10 utilization of TTE is indicated and appropriate in the presence of hemodynamical instability of a suspected cardiac etiology, acute chest pain with suspected MI, or respiratory failure of uncertain etiology. In our hospital, an urgent echocardiogram is usually completed within 2 h. Therefore, if a clinician is suspicious of acute mitral valve disease, an urgent echocardiogram may help reach the correct diagnosis in a timely manner and thus reduce the mortality associated with acute flail mitral valve. If TTE is non-diagnostic, or with poor image quality, TEE may, then be considered to better evaluate valvular structure and function, and also to assess suitability for valve repair.10–12

Consistent with prior studies,3,13–15 our data show that the main cause of acute flail mitral valve is degenerative mitral valve disease, followed by infective endocarditis. Papillary muscle rupture due to acute MI16,17 is relatively rare and is not seen in our series. Moreover, our study reveals that acute flail mitral valve is more frequently seen in elderly male patients with a history of hypertension. The mechanism of this association is uncertain.

5. Study limitations

The main limitation of this report is that this is a retrospective study. There is no long-term follow-up data available. Acute flail mitral valve is a rare disorder. As such, our sample size is quite small, despite representing a collection of such cases over 5 years in an urban academic medical center.

6. Conclusion

Initial misdiagnosis of acute flail mitral valve is not infrequent and often results in morbid outcomes. Clinical history and physical examination are not sensitive enough to make the correct diagnosis. Sometimes CXR can be misleading. Echocardiography is by far the best modality to timely diagnose acute flail mitral valve. Therefore, it is imperative to raise awareness of this clinical entity and use echocardiography appropriately to reduce associated morbidity and mortality.

Source of support

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

Contributor Information

Li Zhou, Email: zhouli@uic.edu.

Michael Grushko, Email: michael.grushko@gmail.com.

James M. Tauras, Email: jtauras@montefiore.org.

Cynthia C. Taub, Email: ctaub@montefiore.org.

References

- 1.Fauci A.S., Braunwald E., Kasper D.L. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 17th ed. The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc; 2008. Valvular heart disease; p. 1469. ch. 230. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fradley M.G., Picard M.H. Rupture of the posteromedial papillary muscle leading to partial flail of the anterior mitral leaflet. Circulation. 2011;123:1044–1045. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.984724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Enriquez-Sarano M., Akins C.W., Vahanian A. Mitral regurgitation. Lancet. 2009;373:1382–1394. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60692-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ling L.H., Enriquez-Sarano M., Seward J.B. Clinical outcome of mitral regurgitation due to flail leaflet. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1417–1423. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199611073351902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenhek R., Rader F., Klaar U. Outcome of watchful waiting in asymptomatic severe mitral regurgitation. Circulation. 2006;113:2238–2244. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.599175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anyanwu A.C., Adams D.H. Etiologic classification of degenerative mitral valve disease: Barlow's disease and fibroelastic deficiency. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;19:90–96. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bayer A.S., Bolger A.F., Taubert K.A. Diagnosis and management of infective endocarditis and its complications. Circulation. 1998;98:2936–2948. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.25.2936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barbieri A., Bursi F., Grigioni F. Prognostic and therapeutic implications of pulmonary hypertension complicating degenerative mitral regurgitation due to flail leaflet: a multicenter long-term international study. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:751–759. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Attias D., Mansencal N., Auvert B. Prevalence, characteristics, and outcomes of patients presenting with cardiogenic unilateral pulmonary edema. Circulation. 2010;122:1109–1115. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.934950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Douglas P.S., Garcia M.J., Haines D.E. ACCF/ASE/AHA/ASNC/HFSA/HRS/SCAI/SCCM/SCCT/SCMR 2011 appropriate use criteria for echocardiography. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation appropriate use criteria Task Force, American Society of Echocardiography, American Heart Association, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Critical Care Medicine, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance American College of Chest Physicians. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2011;24:229–267. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pearson A.C., St Vrain J., Mrosek D., Labovitz A.J. Color Doppler echocardiographic evaluation of patients with a flail mitral leaflet. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;16:232–239. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90483-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Himelman R.B., Kusumoto F., Oken K. The flail mitral valve: echocardiographic findings by precordial and transesophageal imaging and Doppler color flow mapping. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:272–279. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(91)90738-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eishi K. Management of active infective endocarditis. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;56:257–259. doi: 10.1007/s11748-008-0273-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Omoto T., Ohno M., Fukuzumi M. Mitral valve repair for infective endocarditis. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;56:277–280. doi: 10.1007/s11748-007-0209-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu W., Luo X., Wang L. The accuracy of echocardiography versus surgical and pathological classification of patients with ruptured mitral chordae tendineae: a large study in a Chinese cardiovascular center. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;6:94. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-6-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Czarnecki A., Thakrar A., Fang T. Acute severe mitral regurgitation: consideration of papillary muscle architecture. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2008;6:5. doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-6-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lunghetti S., D'Asaro M.G., Guerrieri G. Massive mitral regurgitation secondary to acute ischemic papillary muscle rupture: the role of echocardiography. Cardiol J. 2010;17:397–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]