Abstract

Objective

To assess vasomotor and other menopausal symptoms before, one year later, again at trial closure and after stopping estrogens or placebo. The role of baseline symptoms and age was examined as was the frequency and determinants of hormone use and symptom management strategies after discontinuing conjugated equine estrogens or placebo.

Methods

Intention-to-treat analyses of 10,739 postmenopausal women before and one year after randomization to conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) or placebo at 40 clinical centers, and a cohort analysis of participants (n=3496) who continued taking assigned study pills up to trial closure and completed symptom surveys shortly before (mean 7.4 + 1.1 years from baseline) and after stopping pills (mean 306 + 55 days after trial closure). Generalized linear regression modeled vasomotor symptoms, vaginal dryness, breast tenderness, pain/stiffness and mood swings, as a function of treatment assignment and baseline symptoms, before and after stopping study pills.

Results

Approximately one-third of participants reported at least one moderate-to-severe symptom at baseline. Fewer symptoms were reported with increasing age, except joint pain/stiffness, which was similar among age groups. At one year, hot flashes, night sweats and vaginal dryness were reduced by CEE, whereas, breast tenderness was increased. Breast tenderness was also significantly higher in the CEE group at trial closure. Post-stopping, vasomotor symptoms were reported by significantly more women who had reported symptoms at baseline, compared to those who had not, and by significantly more participants assigned to CEE (9.8%) versus placebo (3.2%); however, among women with no moderate or severe symptoms at baseline, over 5 times as many reported hot flashes after stopping CEE (7.2%) versus placebo (1.5%).

Conclusions

CEE significantly reduced vasomotor symptoms and vaginal dryness in women with baseline symptoms, but increased breast tenderness. The likelihood of experiencing symptoms was significantly higher after stopping CEE than placebo regardless of baseline symptom status. These potential effects should be considered before initiating CEE to relieve menopausal symptoms.

Keywords: estrogen therapy, randomized trial, symptoms, post-menopause

INTRODUCTION

The randomized, placebo-controlled Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) estrogen plus progestin (E+P) trial of postmenopausal women, aged 50–79, reported that the health risks of a mean 5.2 years of combined conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) plus medroxyprogesterone (MPA) clearly outweighed the benefits (1). Soon after, the FDA advised that menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) not be used to prevent chronic diseases, particularly cardiovascular disease (2). Subsequently, many women stopped MHT. Reports from two general practices, with a mean age over 60, indicated that menopausal symptoms returned in over 40% of MHT users who stopped long-term MHT (3, 4), while in a third study, 82% reported symptom return(5).

In the WHI E+P trial, hot flashes, night sweats, vaginal dryness and joint pain/stiffness were significantly reduced one year after initiating CEE+MPA compared to placebo (6); however, other symptoms, including breast tenderness, vaginal discharge, uterine bleeding, and urinary incontinence, increased (6, 7, 8). Furthermore, WHI E+P trial participants who had reported moderate or severe menopausal symptoms at baseline were much more likely to report similar symptoms 8 to 12 months after the 5.6 year trial ended compared to participants who were asymptomatic at baseline; however, those who had been assigned to CEE+MPA were more than five times as likely to report symptoms after discontinuing pills compared to placebo, regardless of the presence or absence of symptoms at baseline (8). Combined with the adverse trial findings (2), the increase in some menopausal symptoms while on CEE+MPA and a higher rate of recurrence of bothersome symptoms upon stopping MHT, raises new questions about MHT for managing menopausal symptoms.

The majority of MHT users in the U.S. are women who have had a hysterectomy and use estrogen without a progestin (10). The risks and benefits over 7 years of CEE alone (i.e. without a progestin) in the WHI trial of 10,379 women with prior hysterectomy (9) were more balanced compared to CEE + MPA. The aforementioned observations indicate the importance of a detailed analysis of menopausal symptoms experienced during and after stopping CEE.

The objectives of the current WHI CEE trial analyses were: first, to compare menopausal symptoms at baseline, one year later and at trial closure (prior to stopping study pills) in active and placebo groups, by age and presence of symptoms at baseline; and, second, to assess determinants of moderate/severe symptoms 6 to 12 months after stopping study pills in participants who continued taking study pills through to study closure; and, finally, to assess the frequency and determinants of MHT use and symptom management strategies after discontinuing CEE or placebo.

METHODS

Details of the WHI CEE trial design, recruitment, randomization, and baseline characteristics of women assigned to CEE or placebo, have been described previously (11–13). Briefly, post-menopausal women, aged 50 to 79 years at initial screening, were eligible if they had a prior hysterectomy and met specific health criteria. The WHI Estrogen-only Trial participants were an average of nearly 20 years post hysterectomy at baseline. The number of years since menopause is more difficult to determine because a high proportion (~40%) had also had a bilateral oophorectomy. Approximately 47% of participants had used MHT in the past, including 13% who were taking MHT at initial screening were required to stop MHT for at least three before randomization, with the recognition that menopausal symptoms may appear on discontinuation. One-third of trial participants reported the presence of one or more moderate-to-severe menopause-associated symptoms at baseline. Prior to randomization, participants completed self-administered questionnaires that included menopausal symptom items, the presence of which were neither required nor exclusionary for study entry; however, women were advised not to join if they were experiencing vasomotor symptoms that seriously disrupted their well-being. Participants were randomized to either 0.625 mg/d CEE (Premarin; Wyeth, St Davids, Pa) or a matching placebo between 1993 and 1998. An independent data and safety monitoring board assessed health risks and benefits. In March 2004, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) terminated the intervention phase of the trial and women were instructed to stop taking study pills; however, close-out visits took place during the originally planned period, between October 2004 and March 2005.

To examine symptoms before and after stopping treatment, an “Estrogen-Alone Survey” was mailed to trial participants who were still taking study pills near the time investigators learned that the trial was being stopped (IRB approval of the stopping process was needed). This survey was reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards for the clinical coordinating center (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center) and local clinical centers. The survey was nearly identical to that administered in the WHI E+P trial, with derivation, pre-testing and validity described in Ockene et al (8) and it had a list of symptoms, the same as that administered at baseline (14). Participants mailed back the questionnaire. Surveys were considered valid if post-marked before March 1, 2004, the date of notification to stop taking study pills. Another administration of the Estrogen-Alone Survey, containing the same symptom list given at baseline, at year 1 and in February 2004, prior to stopping study pills, was completed seven months later, at the study close-out visit, a mean of 306 days after study pills had been stopped. All surveys used the same symptom list. In addition to symptoms, the survey also asked whether participants were currently taking prescription female hormones, non-prescription hormone-containing treatments and “herbal/natural” hormones, plus questions on other medicines used for managing menopausal symptoms. Only participants that were taking study pills prior to the trial stopping were eligible to receive the survey, at close-out, after stopping pills.

The Estrogen-Alone Survey, intended for self-administration, provided the following instructions: Below is a list of symptoms people sometimes have. For each item, mark the one box that best describes how bothersome the symptom was for you during the past 4 weeks. Be sure and mark one box on each line. If you do not have the problem, please mark the box under “Symptom did not occur.” If you have the symptom, use the following key to indicate how bothersome it is: Mild = symptom does not interfere with usual activities. Moderate = symptom interferes somewhat with usual activities. Severe = symptom is so bothersome that usual activities can not be performed.

Statistical Approach and Analysis

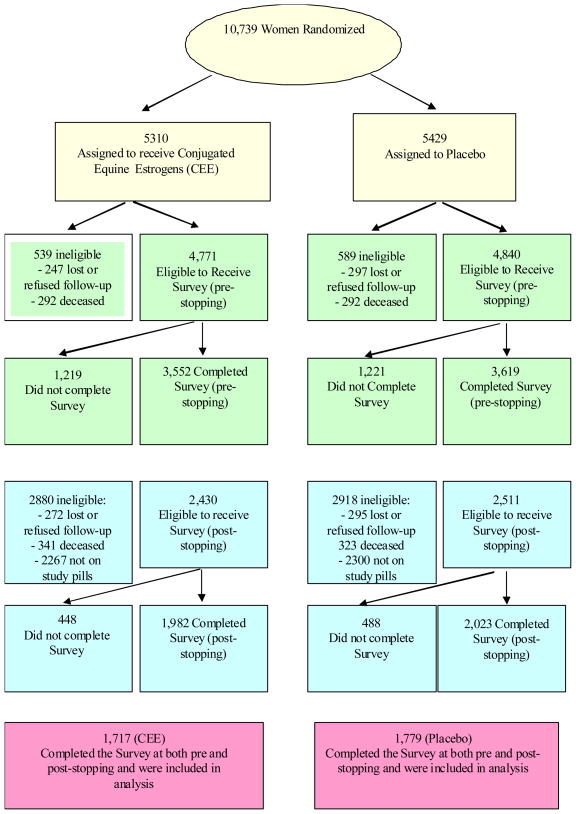

Analysis of WHI CEE clinical trial data (n=10739; yellow boxes in Figure 1), focused on incidence of symptoms at Year 1. Comparisons of active to placebo, stratified by presence or absence of baseline symptoms, are presented as relative risks (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) along with p-values for the main effect of CEE on symptom incidence and p-values for the interaction between CEE and the presence or absence of baseline symptoms (p-int). Estimated RR(95%CIs) and p-values were obtained from generalized linear models. Further analyses were conducted of these relative risks as modified by age.

Fig. 1.

Profile of CEE Hormone Symptom Survey Respondents Pre-stopping and Post-stopping. Yellow depicts Screening and Baseline for the full cohort. Green presents subset of women receiving the pre-stopping survey. Blue presents subset of women who were still taking study pills March 2004 and received a post-stopping survey. Pink presents the N of women who completed the pre and post-stopping Estrogen-Only surveys.

A similar analysis of the pre and post-stopping incidence data from the Estrogen-Alone Survey was also conducted; comparisons of incidence prior to stopping were stratified by baseline symptoms, and comparison of incidence post-stopping was stratified by baseline symptoms and separately symptoms prior to stopping. This analysis included the WHI CEE trial participants (n=3496; see red boxes in figure 1) who were taking study pills at trial closure and had completed both Estrogen-Alone Surveys prior to stopping study pills (green boxes in Figure 1) and after stopping study pills (blue boxes in Figure 1). This portion of the study is comprised of a unique subsample of the randomized participants and may be considered observational. To examine selection bias and to better understand the limitations of the analysis, demographic and health parameters of the subset of respondents were compared with the whole CEE trial cohort. The analyses differ from those described in the pre-set protocol for the HT clinical trial as both on-trial and post-trial data are considered. Estimated RR(95%CIs) and p-values were obtained from generalized linear models that were adjusted for potential confounders. For this subsample, age, years since menopause and prior history of HT use were significantly associated with treatment assignment (p<0.05) and identified as potential confounders.

For all testing, p-values were two sided and P≤.05 was designated as significant. All analyses were conducted with SAS version 9.0 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary NC).

RESULTS

Figure 1 depicts eligibility and actual participation at the pre- and post-stopping data collection points for the subset of participants who were still taking study pills March 2004 when study pill administration was halted (N=3496).

Randomized Trial Analyses

Table 1 shows the proportion of women by age who reported specific symptoms, at baseline, i.e. before study treatment began for all women who were randomized. Over 20% of women in age groups 50 to 54 and 55 to 59 years reported vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes or night sweats); whereas, a much lower proportion of women aged 60–69 and an even lower percent of women aged 70–79 reported these symptoms. Vaginal dryness and breast tenderness were also reported by a smaller proportion of women from youngest to oldest age groups; while joint pain was reported by about 30% of women of all ages. Moderate or severe sleep disturbance at baseline was also reported by about a third of women, with slightly declining proportions with age.

Table 1.

Reported Prevalence of Baseline Symptoms by Age for WHI ET Trial Women (n=10739)

| Symptom | Age Group (years) | P1 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 50–54 | 55–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | |||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Hot flashes | 1343 | 12.6 | 333 | 24.1 | 399 | 21.0 | 477 | 9.9 | 134 | 5.3 | <0.001 |

| Night sweats | 1377 | 13.0 | 305 | 22.2 | 378 | 19.9 | 526 | 11.0 | 168 | 6.6 | <0.001 |

| Breast Tenderness | 367 | 3.5 | 80 | 5.8 | 81 | 4.3 | 158 | 3.3 | 48 | 1.9 | <0.001 |

| Vaginal or genital dryness | 1145 | 10.8 | 170 | 12.3 | 255 | 13.4 | 524 | 10.9 | 196 | 7.7 | <0.001 |

| Joint pain or stiffness | 3364 | 31.7 | 390 | 28.3 | 639 | 33.6 | 1512 | 31.5 | 823 | 32.4 | 0.11 |

| Mood swings | 838 | 7.9 | 189 | 13.7 | 220 | 11.6 | 315 | 6.6 | 114 | 4.5 | <0.001 |

Cochran-Armitage Test for trend.

Baseline to Year 1 Treatment Effects

Table 2 shows the proportion of women reporting specific symptoms at Year 1 post-randomization by presence of relevant symptoms at baseline and the corresponding relative risks for CEE versus placebo, as well as whether the presence of the symptom at baseline interacted with treatment assignment to affect Year 1 symptoms (shown as the P-int). For women either with or without the symptoms at baseline, CEE had a greater effect in reducing or preventing hot flashes, night sweats and vaginal dryness than placebo (each p < .001). There was a marginal effect of CEE on joint pain (p < .04) and no effect of CEE or placebo on mood swings and sleep disturbance (data not shown) and no differences comparing women with or without these symptoms at baseline. In contrast, CEE increased (p < .001) the risk of breast tenderness more than placebo in groups both reporting and not reporting the symptom at baseline. In absolute terms, breast tenderness occurred in about 3% of the population. This side effect was significantly (p <0.001) higher among subjects who did not have breast tenderness at baseline but the differential effect was smaller than for hot flashes and night sweats. CEE was not effective in reducing or preventing reported mood swings. Risk for breast tenderness increased with age (p-int<0.001), RR (95% CI) 1.45 (1.04, 2.10), for women aged 50 to 59; 2.59 (1.99, 3.36), for 60 to 69 year old women; and 4.35, (2.91, 6.51) for 70 to 79 years of age. No age related trends were found for the other symptoms (p-int > 0.25).

Table 2.

Risk of Incident Symptoms1 at Year 1 by Prevalence of Symptoms2 at Baseline: WHI CEE trial (N = 10739)

| Baseline Symptom Prevalence | CEE Year 1 %3 (n4) | Placebo Year 1 % (n) | Risk Ratio (95% CI)5 | P6 | P-int7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hot Flashes | |||||

| Not present | 1.8 (4176) | 4.3 (4269) | 0.43 (0.33, 0.56) | <0.001 | 0.26 |

| Present | 20.2 (583) | 39.3 (590) | 0.51 (0.43, 0.62) | ||

| Night Sweats | |||||

| Not Present | 3.9 (4136) | 6.4 (4232) | 0.61 (0.51, 0.74) | <0.001 | 0.83 |

| Present | 24.9 (595) | 39.5 (598) | 0.63 (0.53, 0.75) | ||

| Breast Tenderness | |||||

| Not Present | 8.4 (4597) | 3.4 (4708) | 2.48 (2.08, 2.97) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Present | 35.0 (160) | 32.9 (155) | 1.06 (0.78, 1.45) | ||

| Vaginal Dryness | |||||

| Not Present | 4.1 (4227) | 5.2 (4298) | 0.79 (0.65, 0.96) | <0.001 | 0.92 |

| Present | 34.3 (499) | 42.9 (522) | 0.80 (0.68, 0.93) | ||

| Joint Pain | |||||

| Not Present | 16.2 (3261) | 17.9 (3333) | 0.91 (0.81, 1.01) | 0.04 | 0.20 |

| Present | 66.1 (1467) | 67.6 (1520) | 0.98 (0.93, 1.03) | ||

| Mood Swings | |||||

| Not Present | 5.4 (4349) | 5.3 (4513) | 1.02 (0.86, 1.22) | 0.45 | 0.80 |

| Present | 41.6 (377) | 42.2 (344) | 0.99 (0.83, 1.17) | ||

Incidence of moderate or severe symptoms.

Presence of moderate or severe symptoms reported at baseline.

Proportion of N reporting symptoms at Year 1.

Number of participants in CEE or placebo with or without baseline symptom; denominator of (3).

Relative risk (95% confidence interval) of symptoms at Year 1 of CEE compared to placebo.

Test of main effect; corresponds to whether RR of CEE compared to placebo differs from unity regardless of presence or absence of baseline symptoms.

Test of interaction; corresponds to whether RR of CEE compared to placebo differs by presence or absence of baseline symptom.

Subsample (Observational) Analyses: Participants Taking Assigned Study Pills at Trial End and Completing Pre- and Post-stopping Surveys

The subsample of participants who were still taking assigned study pills at the time the trial was stopped. and who completed pre- and post-stopping Estrogen-Alone Surveys, differed somewhat in baseline vasomotor symptoms compared to women not taking pills (and therefore ineligible for these surveys; 2.5% lower for eligible subjects, p = 0.002).

At the time the intervention was stopped (mean 7.1 years, range 5.7 to 10.7 years from baseline), 46% of the CEE trial cohort was still taking study pills and 71% of these women completed both pre-stopping and post stopping symptom questionnaires (Figure 1). A mean of 306 ± 55 days elapsed between pre- and post-stopping surveys. The mean age (active 63.0 ± 7.0 vs. placebo 63.6 ± 7.1 years) and years since menopause (active 18.5 + 9.7 vs. 18.9 + 9.6 years) were similar between groups

The proportion of women reporting hot flashes and night sweats had declined by trial closure (pre-stopping) compared to baseline to about 11%, independent of age, and both of these symptoms were significantly reduced in the CEE treatment group. The proportion of women reporting breast tenderness was significantly higher with CEE than placebo at trial closure (Table 3) but again was an infrequent symptom in absolute terms.

Table 3.

Multivariable Adjusted1 Risk of Incident Symptoms Prior to stopping2 by Prevalence of Symptoms at Baseline3: WHI CEE cohort (n=3496)4

| Symptom Prevalence At Baseline | CEE %5 (N6) | Placebo % (N) | RR (95% CI)7 | P8 | P-int9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hot Flashes | |||||

| Not present | 0.9 (1460) | 2.3 (1557) | 0.42 (0.22, 0.81) | 0.01 | 0.36 |

| Present | 10.1 (218) | 15.9 (176) | 0.62 (0.36, 1.06) | ||

| Night Sweats | |||||

| Not Present | 3.4 (1450) | 4.3 (1547) | 0.83 (0.57, 1.21) | 0.04 | 0.23 |

| Present | 15.7 (223) | 27.3 (172) | 0.59 (0.40, 0.88) | ||

| Breast Tenderness | |||||

| Not Present | 4.3 (1642) | 2.3 (1706) | 1.81 (1.20, 2.75) | 0.002 | 0.59 |

| Present | 40.0 (35) | 23.3 (30) | 1.42 (0.65, 3.06) | ||

| Vaginal Dryness | |||||

| Not Present | 5.3 (1508) | 5.4 (1586) | 0.99 (0.72, 1.35) | 0.52 | 0.26 |

| Present | 25.6 (164) | 36.1 (147) | 0.76 (0.54, 1.07) | ||

| Joint Pain | |||||

| Not Present | 20.4 (1213) | 19.5 (1248) | 1.08 (0.91, 1.28) | 0.15 | 0.98 |

| Present | 58.0 (462) | 52.9 (484) | 1.08 (0.96, 1.22) | ||

| Mood Swings | |||||

| Not Present | 4.7 (1559) | 4.2 (1624) | 1.21 (0.85, 1.73) | 0.59 | 0.19 |

| Present | 28.6 (112) | 30.5 (105) | 0.83 (0.54, 1.27) | ||

Adjusted for age at baseline, years since menopause and prior hormone use.

Incidence of moderate or severe symptoms prior to stopping study pills.

Prevalence of moderate or severe symptoms at Baseline.

Women that were eligible (were not deceased, stopped or lost to follow-up and were still taking study pills) and completed all surveys

Proportion of N reporting symptoms prior to stopping study pills.

N = total number of participants; denominator of (5).

Multivariable adjusted relative risk (95% confidence interval) of symptoms at prior to stopping of CEE compared to placebo.

Test of main effect.

Test of interaction.

Among women still taking study pills, women on CEE who were not experiencing hot flashes at baseline were more likely to report moderate-to-severe hot flashes after stopping pills than women on placebo (Table 4). A similar pattern was seen for night sweats although the interaction was not statistically significant. Women on CEE were also more likely (increase of about 8%) to report joint pain after stopping regardless of whether the symptom was present or absent prior to stopping.

Table 4.

Multivariable Adjusted1 Risk of Incident Symptoms at Post-Stopping2 by Prevalence of Baseline Symptoms3: WHI CEE sub-sample (n=3496)4

| Symptom Prevalence at Baseline | CEE %5 (N6) | Placebo % (N) | RR (95% CI)7 | P8 | P-int9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hot Flashes | |||||

| Without Symptoms | 7.2 (1471) | 1.5 (1562) | 5.01 (3.12, 8.04) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| With Symptoms | 28.6 (217) | 19.9 (181) | 1.30 (0.90, 1.88) | ||

| Night sweats | |||||

| Without Symptoms | 8.0 (1454) | 3.8 (1557) | 1.95 (1.42, 2.67) | <0.001 | 0.13 |

| With Symptoms | 31.3 (224) | 23.0 (178) | 1.35 (0.96, 1.90) | ||

| Breast Tenderness | |||||

| Without Symptoms | 2.2 (1653) | 1.6 (1716) | 1.53 (0.90, 2.58) | 0.04 | 0.19 |

| With Symptoms | 17.1 (35) | 3.6 (28) | 4.79 (0.63, 6.66) | ||

| Vaginal Dryness | |||||

| Without Symptoms | 3.2 (1519) | 3.3 (1582) | 0.86 (0.57, 1.30) | 0.89 | 0.31 |

| With Symptoms | 24.4 (160) | 19.9 (151) | 1.17 (0.77, 1.77) | ||

| Joint Pain | |||||

| Without Symptoms | 22.2 (1211) | 17.3 (1252) | 1.35 (1.13, 1.60) | <0.001 | 0.07 |

| With Symptoms | 59.6 (465) | 51.2 (494) | 1.11 (0.98, 1.25) | ||

| Mood Swings | |||||

| Without Symptoms | 4.1 (1563) | 3.1 (1640) | 1.33 (0.90, 1.96) | 0.51 | 0.10 |

| With Symptoms | 22.1 (113) | 25.7 (105) | 0.77 (0.46, 1.29) | ||

Adjusted for age at baseline, years since menopause and prior hormone use.

Incidence of moderate or severe symptoms after stopping study pills.

Prevalence of moderate or severe symptoms at baseline.

Women that were eligible (were not deceased, stopped or lost to follow-up and were still taking study pills) and completed all surveys.

Proportion of N reporting symptoms post-stopping.

N= total number of participants; denominator of (5).

Multivariable adjusted relative risk (95% confidence interval) of symptoms at post-stopping of CEE compared to placebo.

Test of main effect.

Test of interaction.

Among women still taking study pills, those assigned to CEE who had not reported hot flashes or night sweats prior to stopping were more likely to report hot flashes and night sweats after stopping compared to placebo (Table 5). It should be noted that in absolute numbers about 3% of women reported these symptoms. A similar pattern was seen for breast tenderness, although the interaction was not statistically significant.

Table 5.

Multivariable Adjusted1 Risk of Incident Symptoms at Post-stopping2 by Prevalence of Symptoms Prior to Stopping3: WHI CEE sub-sample (n=3496)4

| Symptom Prevalence Prior to Stopping | CEE %5 (N)6 | Placebo % (N) | RR (95% CI)7 | P8 | P-int9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hot Flashes | |||||

| Not present | 9.3 (1640) | 2.2 (1663) | 3.64 (2.54, 5.20) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Present | 35.3 (34) | 30.6 (62) | 0.85 (0.44, 1.64) | ||

| Night Sweats | |||||

| Not Present | 9.3 (1588) | 3.4 (1610) | 2.30 (1.69, 3.13) | <0.001 | 0.008 |

| Present | 46.4 (84) | 36.8 (114) | 1.18 (0.82, 1.71) | ||

| Breast Sensitivity | |||||

| Not Present | 1.8 (1589) | 1.2 (1688) | 1.66 (0.89, 3.09) | 0.03 | 0.41 |

| Present | 18.1 (83) | 17.8 (45) | 1.06 (0.47, 2.39) | ||

| Vaginal Dryness | |||||

| Not Present | 3.2 (1546) | 2.4 (1586) | 1.36 (0.87, 2.11) | 0.87 | 0.12 |

| Present | 32.2 (118) | 30.9 (136) | 0.85 (0.58, 1.25) | ||

| Joint Pain | |||||

| Not Present | 18.3 (1146) | 15.4 (1231) | 1.24 (1.02, 1.51) | <0.001 | 0.47 |

| Present | 64.6 (511) | 55.1 (497) | 1.14 (1.03, 1.27) | ||

| Mood Swings | |||||

| Not Present | 3.4 (1561) | 2.8 (1624) | 1.17 (0.77, 1.78) | 0.54 | 0.80 |

| Present | 34.0 (103) | 29.0 (100) | 1.27 (0.79, 2.05) | ||

Adjusted for age at prior to stopping, years since menopause, prior hormone use and presence of baseline vasomotor symptoms.

Incidence of moderate or severe symptoms after stopping study pills.

Prevalence of moderate or severe symptoms prior to stopping study pills.

Women that were eligible (were not deceased, stopped or lost to follow-up and were still taking study pills) and completed all surveys.

Proportion of N reporting symptoms post-stopping.

Number of participants in CEE or placebo with or without symptom prior to stopping, denominator of (5).

Multivariate adjusted relative risk (95% confidence interval) of symptoms at post-stopping of CEE compared to placebo.

Test of main effect.

Test of interaction.

Older women were at higher risk for joint pain after stopping CEE, compared to placebo pills (p-int=0.04). The same trend existed for both previously asymptomatic and symptomatic women with RR(95%) of 0.98 (0.51, 1.89) for women aged 50–59, 1.23 (0.90, 1.67) ages 60–69; and 1.30 (0.99, 1.71) for ages 70–79 for the asymptomatic women and .81 (0.60, 1.08), 1.09 (0.93, 1.28), and 1.26 (1.08, 1.48) for the symptomatic women by these age groups respectively.

Life style Strategies

After the trial ended, 4.5% of women reported taking prescription hormones. Only 1.8% of subjects who had been on placebo used prescription hormones after trial closure, compared to 7.2% of those who had been on CEE. Most (89%) women did not start any type of hormone therapy, either prescribed or over the counter after the trial ended (Table 6). Women taking HT (non-prescription and/or prescription) after stopping, when compared to women that did not begin taking HT after stopping, were more likely to have been randomized to active intervention (p<0.001), had experienced baseline vasomotor symptoms (p<0.001), and reported current HT use at baseline (p<0.001).

Table 6.

Baseline characteristics and use of HT post stopping in women who completed both pre-stopping post-stopping HT use questionnaires (n =3496)

| Currently take prescription and non-prescription hormones (n=13) | Currently take prescription hormones (n=141) | Currently take natural (non-prescription) hormones (n=127) | No current hormone use (n=3119) | P-Value36 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| HT Use | |||||||||

| Placebo | 1 | 7.7 | 30 | 21.3 | 54 | 42.5 | 1639 | 52.5 | <0.001 |

| CEE | 12 | 92.3 | 111 | 78.7 | 73 | 57.5 | 1480 | 47.5 | |

| Moderate/severe vasomotor symptoms | |||||||||

| No | 10 | 76.9 | 103 | 73.2 | 96 | 75.2 | 2658 | 85.2 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 3 | 23.1 | 38 | 26.8 | 31 | 24.8 | 461 | 14.8 | |

| HT Usage Status at Baseline | |||||||||

| Never used | 5 | 38.5 | 53 | 37.6 | 48 | 37.8 | 1536 | 49.3 | <0.001 |

| Past user | 0 | 0.0 | 43 | 30.5 | 42 | 33.1 | 1133 | 36.3 | |

| Current user | 8 | 61.5 | 45 | 31.9 | 37 | 29.1 | 448 | 14.4 | |

Chi-squared test of association.

The most frequently cited reason for starting treatment after the trial was to “deal with symptoms” (reported by 61% of the 158 women who began taking hormones), with “advice from health care provider” cited by 42% and “to feel better” by 40% in this same group, and prevention of osteoporosis was cited by 18%; whereas, “other disease” prevention was cited by 6%.

DISCUSSION

The WHI Estrogen-only Trial participants were nearly 20 years post hysterectomy at baseline and a large proportion (~40%) had had a bilateral oophorectomy; furthermore, about 13% had been taking MHT until about 3 months prior to being randomized into the trial; therefore the timing of menopause was difficult to determine. At study baseline approximately 12.5% of women reported moderate to severe hot flashes and night sweats, 10.7% reported vaginal dryness and 3.5% reported breast tenderness, with the proportion decreasing by baseline age for most symptoms, except for joint pain/stiffness, which nearly one-third of women reported in all age groups. One year after randomization to CEE or placebo, several symptoms, i.e. hot flashes, night sweats and vaginal dryness, were significantly improved by CEE, whereas, breast tenderness/sensitivity was significantly worsened, compared to placebo. CEE did not significantly affect mood, joint pain or sleep (data not shown) one year after baseline.

In the women who were still taking study pills at trial closure i.e. approximately 46% of the cohort, symptoms were assessed again prior to breaking the treatment blind. At this time-point, 7.1 years after baseline, CEE continued to be associated with fewer hot flashes (but not reduced night sweats) and with increased breast tenderness compared to placebo. We assessed symptoms in this subset, a mean of 306 ± 55 days after the study pills had been stopped and participants had learned their treatment assignment. At this point, symptoms were reported by significantly more women who reported them at baseline and by more women who had been assigned to CEE than placebo. Furthermore, among women who did not have moderate or severe vasomotor symptoms at baseline, those assigned to CEE were significantly more likely to report symptoms after stopping study pills than were those assigned to placebo (7.2% and 1.5% respectively, RR5.01).

Observational studies and clinical experience have shown that vasomotor symptoms occur after stopping menopausal hormone treatment (3) even if treatment is long-term and the withdrawal is gradual (15). In the WHI trial of combined CEE+MPA, discontinuation of active treatment was shown to increase the risk of symptoms (vasomotor and joint stiffness) by more than 4 times in women with prior symptoms and by 7 times in those without prior symptoms, compared to placebo. Thus, it appears that CEE, with or without progestin may promote vasomotor symptoms when treatment is withdrawn, regardless of whether symptoms were present at baseline.

In addition to vasomotor symptoms, joint pain/stiffness had been 5% lower during treatment (year 1) with CEE than with placebo but this suppression reversed after stopping study pills. Significantly more (5.4%) women in the CEE group compared to the placebo group reported joint pain/stiffness after stopping. The incidence of breast tenderness/sensitivity was only marginally higher after discontinuation of active treatment compared to placebo (respectively 2.5% and 0.9%), indicating a rapid decline in estrogen-induced breast tenderness upon discontinuation of therapy.

Only 4.5% of women reported taking prescription hormones on the post-trial questionnaire (about 10 months after the end of the trial). This is in contrast to the report from a Kaiser Foundation observational study in which about 26% of women restarted within a year after stopping (16). Reasons for stopping were not assessed but the development of either troublesome vasomotor symptoms or other troublesome symptoms was each independently associated with unsuccessful stopping. Most studies of stopping MHT examined women who stopped because of the WHI results and in these 18% to 28% re-started (5, 17). There are a number of factors that would explain a higher restarting rate in patients in other studies who had stopped hormone therapy compared to our research cohort including differences in age, symptom severity, personal inclination to choose hormones, treatment flexibility, non-placebo nature of the treatment and provider influence.

The Women’s Health Initiative is the largest study to look at symptoms after stopping hormones. Since this study was conducted among women specifically selected to participate in a clinical trial, the generalizability of the findings to women of this age in the population is uncertain. Further, several of the findings are limited to the approximately 46% of participants in the active treatment and placebo groups still adherent to their assigned study pills by the end of the trial. Some women who stopped study pills early initiated hormones through their private health care provider (5.7% in the CEE group; 9.1% in the placebo group). Another limitation is that we tested only one hormone formulation and only one mode of delivery; and began with women who indicated they could tolerate symptoms without hormone treatment. We do not therefore know how well the findings generalize beyond the treatments and population studied; older women may regard symptoms differently than younger women with recent hysterectomy. Knowledge of treatment assignment (i.e. participants were no longer blinded) may have influenced responses in that administration of the post-stopping survey was not blinded. Additionally, the cohort of participants who continued to take study pills until the end of the trial differed in several characteristics documented at baseline from those who stopped early. It is important, however, that there were no significant differences in baseline vasomotor symptoms between respondents and non-respondents to the surveys.

Both WHI hormone trials demonstrate that for many women, menopause-related vasomotor symptoms will abate over time without any intervention. Our findings are also consistent with studies showing that for some women symptoms and conditions associated with the menopausal transition may continue for many years and may reappear or appear as new symptoms, upon discontinuation of hormone therapy (18). Others have shown that moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms, sleep difficulties, depression and pain appear at the menopause transition in less than half of women studied (19). In that study, hot flashes and night sweats were more common three years after menopause than in peri-menopause or one year after menopause. Gold, Colvin, Avis et al (20) also found that symptoms were reported nearly as often in post-menopause as in peri-menopause.

We found that hormone therapy may postpone symptoms for many years in some women with hysterectomy. In absolute terms, among women with vasomotor symptoms at baseline, we found that only 10.1% had hot flashes and 15.7% had night sweats after an average of 7.4 years on CEE. However, among these same women with vasomotor symptoms at baseline, the percentage of hot flashes and night sweats increased from these pre-stopping rates to 28.6% and 31.3%, respectively, after stopping study hormones at a mean age of 73 years. Thus it appeared that for some symptomatic women, CEE like CEE + MPA therapy relieved several symptoms (except for breast tenderness which increased) but did not permanently eliminate them. This recurrence phenomenon may make it difficult for some symptomatic women to follow the consensus recommendation to use MHT for a short period of time. One position statement noted that management of severe symptoms is a primary basis for extended use of HT “for the woman for whom, in her own opinion, the benefits of menopause symptom relief outweigh risks, notably after an attempt to stop HT” (21).

CONCLUSIONS

These findings support current recommendations not to initiate MHT for women without symptoms, except as a treatment for prevention of osteoporosis. For clinicians advising women who are experiencing symptoms, this study confirms the beneficial effects of MHT on symptoms while on treatment and offers additional data about the possibility of experiencing symptoms post-stopping, even after long-term therapy. This information is particularly relevant, given current recommendations to prescribe MHT in the lowest effective dose and for the shortest duration consistent with individual treatment goals and risks.. Future research may be directed at continuing to characterize the intensity and duration of recurrent menopausal symptoms, the women at highest risk for recurrence, and the physiological mechanisms that are involved.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: The Women’s Health Initiative program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services.

Role of the Sponsor: The National Institutes of Health had input into the design and conduct of the study and in the review and approval of this article.

Footnotes

Trial Registration: clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00000611

Author Contributions: Drs Brunner and Stefanick and Mr Aragaki had full access to all of the data and take full responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Barnaabei, Brunner, Stefanick, Cochrane, Ockene, Woods

Acquisition of data: Brunner, Gass, Hendrix, Lane, Ockene, Stefanick, Woods.

Analysis and interpretation of the data: Aragaki, Barnabei, Brunner, Cochrane, Lane, Ockene, Stefanick, Woods

Drafting of the manuscript: Barnabei, Brunner, Stefanick, Ockene.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Aragaki, Barnabei, Brunner, Cochrane, Gass, Hendrix, Lane, Ockene, Stefanick, Woods, Yasmeen.

Statistical analysis: Aragaki.

Obtained funding: Brunner, Gass, Hendrix, Lane, Ockene, Stefanick.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Cochrane

Study supervision: Brunner, Gass, Hendrix, Lane, Ockene, Stefanick.

Financial Disclosures: Dr Gass reports that she has received funding support for multisite clinical trials from Procter & Gamble Pharmaceuticals, Roche, and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, and honoraria from Aventis, Eli Lilly & Co, Esprit Pharma, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Merck & Co Inc, Procter & Gamble Pharmaceuticals, Roche, Upsher-Smith Laboratories Inc, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc. Otherwise, no other authors reported financial conflicts.

Contributor Information

Robert L. Brunner, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Nevada School of Medicine, Reno, NV 89511.

Aaron Aragaki, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, 1100 Fairview Ave N, M3-A410, P.O. Box 19024, Seattle WA 98109-1024.

Vanessa Barnabei, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI 53226.

Barbara B. Cochrane, Family and Child Nursing, Box 357262, University of Washington, Seattle WA 98195-7262.

Margery Gass, North American Menopause Society, Post Office Box 94527, Cleveland, 44101.

Susan Hendrix, University Women’s Care Inc., Detroit MI 48201.

Dorothy Lane, Department of Preventive Medicine, School of Medicine Health Sciences Center L3 086, SUNY at Stony Brook, Stony Brook, NY 11790-8036.

Judith Ockene, Division of Preventive & Behavioral Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical College, Worcester, MA 01655.

Marcia Stefanick, Stanford Prevention Research Center Hoover Pavilion, Room N 229, 211 Quarry Road, MC: 5705, Stanford, California 94305-5705.

Nancy F. Woods, Family and Child Nursing, Box 357262, University of Washington Seattle, WA 98195-7262.

Shagufta Yasmeen, Lawrence J. Ellison Ambulatory Care Center, University of California Davis Health System, Sacramento, CA 95817.

References

- 1.Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in health postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.FDA Updates Menopausal Hormone Information for Postmenopausal Women. US Department of Health and Human Services. US Food and Drug Administration (website); Feb 10, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haskell SG. After the Women’s Health Initiative: Postmenopausal women’s experiences with discontinuing estrogen replacement therapy. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2004;13:438–42. doi: 10.1089/154099904323087132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ness J, Aronow WS, Beck G. Menopausal symptoms after cessation of hormone replacement therapy. Maturitas. 2006;53:356–61. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schonberg MA, Wee CC. Menopausal symptom management and prevention counseling after the Women’s Health Initiative among women seen in an internal medicine practice. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2005;14:507–14. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2005.14.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnabei VM, Cochrane B, Aragaki A, et al. The effects of estrogen plus progestin on menopausal symptoms and treatment effects among participants of the Women’s Health Initiative. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1063–73. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000158120.47542.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hendrix SL, Cochrane BB, Nygaard IE, Handa VL, Barnabei VM, Iglesia C, Aragaki A, Naughton MJ, Wallace RB, McNeeley SG. Effects of estrogen with and without progestin on urinary incontinence. JAMA. 2005;293:935–48. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.8.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ockene JK, Barad DH, Cochrane BB, et al. Symptom experience after discontinuing use of estrogen plus progestin. JAMA. 2005;294:183–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartsfield CL, Connelly MT, Newton KM, Andrade SE, Wei F, Buist DS. Health system responses to the Women’s Health Initiative findings on estrogen and progestin: organizational response. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2005;35:113–5. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgi048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hersh AL, Stefanick ML, Stafford RS. National use of post-menopausal hormone therapy: annual trends and response to recent evidence, 1995–2003. JAMA. 2004;291:47–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Women’s Health Initiative Steering Committee. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy The Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1701–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hays J, Hunt J, Hubbell FA, Anderson GL, Limacher M, Allen C, Rossouw JE. The Women’s Health Initiative recruitment methods and results. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13:S18–S77. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(03)00042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stefanick ML, Cochrane BB, Hsia J, Barad DH, Liu JH, Johnson SR. The Women’s Health Initiative postmenopausal hormone trials: overview and baseline characteristics of participants. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13 (9 Suppl):S78–86. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(03)00045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(this is the same as reference #3) Barnabei VM, Cochrane BB, Aragaki AK, Nygaard I, Williams RS, Mcgovern PG, Young RL, Wells ED, O’Sullivan MJ, Chen B, Schenken R, Johnson SR for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Menopausal symptoms and treatment-related effects of estrogen and progestin in the Women’s Health Initiative. Obstetrics Gynecol. 2005;105:1063. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000158120.47542.18.

- 15.Haimov-Kochman R, Barak-Glantz E, Arbel R, Leefsma M, Brzezinski A, Milwidsky A, Hochner-Celnikier D. Gradual discontinuation of hormone therapy does not prevent the reappearance of climacteric symptoms: a randomized prospective study. Menopause. 2006;13:370–6. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000186663.36211.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grady D, Ettinger B, Tosteson ANA, Pressman A, Macer JL. Predictors of difficulty when discontinuing postmenopausal hormone therapy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:1233–9. doi: 10.1016/j.obstetgynecol.2003.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Helenius IM, Korenstein D, Halm EA. Changing use of hormone therapy among minority women since the Women’s Health Initiative. Menopause. 2007;14:216–22. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000233169.65045.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li C, Samsioe G, Borgfeldt C, Lidfeldt J, Agardh CD, Nerbrand C. Menopause-related symptoms: What are the background factors? A prospective population-based cohort study of Swedish women (The Women’s Health in Lund Area study) Am J Obst Gyn. 2003;189:1646–53. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(03)00872-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dennerstein L, Dudley EC, Hopper JL, Guthrie JR, Burger HG. A prospective population based study of menopausal symptoms. Obst Gynecol. 2000;96:351–8. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00930-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gold EB, Colvin A, Avis N, Bromberger J, Greendale GA, Powell L, Sternfeld B, Matthews K. Longitudinal analysis of the association between vasomotor symptoms and race/ethnicity across the menopausal transition: study of women’s health across the nation. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1226–35. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Position Statement. Estrogen and progestogen use in peri- and post-menopausal women: March 2007 position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2007;14:168–82. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31803167ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]