Abstract

Dating violence among college aged couples has become a growing concern with increasing prevalence. The current study investigated the interplay among witnessing violence during childhood (both parental conflict and parent to child aggression), attachment insecurity, egalitarian attitude within the relationship, and dating aggression. Participants of this study included 87 couples. Results from the structural equation model indicated that the proposed model provided a good fit to the with a χ2 to df ratio of 1.84. In particular, both female and male participants who reported higher levels of attachment insecurity were more likely to be victim of dating aggression in their relationships. Furthermore, female participants who reported having witnessed parental conflict were more likely to be victimized by their partners. In conclusion, this study provides a comprehensive understanding of intimate relationship violence with dyadic data showing, for both genders, attachment insecurity is a crucial factor in both victimization and perpetration of aggression.

Keywords: abuse, attachment, gender, victimization, perpetration

Due to its serious consequences, violence in intimate relationships has been a topic of great concern for social scientists. Previous reports indicate that 66% of college-aged dating students experience at least one incident of physical, sexual, and verbal aggression (Smith, White, & Holland, 2003). Violence within intimate relationships is viewed in several different ways. Family researchers often cite actions such as pushing, slapping, and shoving as mild forms of violence, but others refer to these actions as ‘abuse’ or ‘physical aggression’ (O’Leary, 1993; Straus, Gelles, & Steinmetz, 1980). Criminologists, on the other hand, categorize such events as “violent” only if they cause physical injury. Yet some feminists conceptualize violence as males’ attempts to overpower and terrorize female victims. According to some researchers, severe psychological abuse and intimidation are also components of intimate partner violence (Yllo, 1993).

Different forms and definitions, as well as different correlates of intimate partner violence, call for investigation of the complex factors that underlie this devastating problem. Rather than seeing violence as a one dimensional issue, researchers increasingly agree on its multifaceted nature. Furthermore, past research has concentrated mostly on individual perspectives in understanding the context in which violent behaviors emerge, rather than on dyadic perspectives (O’Leary, Smith-Slep, & O’Leary, 2007). Dyadic patterns, as well as multidimensional conceptualizations, are crucial for more complete understanding of intimate violence.

Recently, many researchers proposed multidimensional models of violence from a theoretical perspective (e.g., Archer (2000), Bell and Naugle, (2008) and Finkel (2007)). In particular, Bell and Naugle (2008) proposed a contextual framework that integrates social learning, background situational, personality, and feminist and power theories.

While theoretical perspectives into the multifaceted nature of violence provide important insights, these perspectives also require empirical validation. In an attempt to empirically explore multiple dimensions of intimate violence, O’Leary et al. (2007) proposed a model that integrates feminist perspectives, relationship dynamics, individual psychopathology, and potential risk factors. Their findings indicated that dominance/jealousy, marital adjustment, and partner responsibility are the three important factors that have direct paths to partner violence for both males and females. However, while O’Leary and colleagues’ (2007) study emphasized relationship dynamics, they did not explicitly hypothesize a dyadic model. Furthermore, their model did not include an assessment of the partners’ attachment security. However, both of these factors were shown to be critical in explaining intimate partner violence. Therefore, inclusion of attachment styles is likely to lead to a more comprehensive multi-dimensional model of relationship aggression.

In this study, we focus on relationship aggression among college students. Intimate partner aggression is more prevalent among college aged couples as compared to the rest of the population. In a review of studies that span 31 universities in 16 countries, Straus (2004a) found that 29% of the 8666 students surveyed had physically assaulted a dating partner in the year prior to the study. Furthermore, 7% of the students had physically injured a partner. Interestingly, these rates were similar for men and women. In another study, Harned (2001) found that male and female university students in the United States (n = 874) reported comparable levels of aggression from dating partners. However, Harned’s results showed that men and women differ in the manner of violence experienced; men reported being subject to more psychological aggression than women (respectively 87% vs. 82%), while women reported more sexual victimization then men (respectively 39% vs. 30%).

The current study also builds on previous theoretical and empirical studies to develop a dyadic model that includes attachment styles in addition to other personal, relationship, and social factors. In doing so, the current study aims to develop a comprehensive framework that incorporates multiple factors in one model. Clearly, this approach requires broader theoretical conceptualization, including incorporation of various theoretical frameworks to elucidate as many potential correlates of intimate partner aggression as possible, as well as potential interactions among these factors. For this reason, the model proposed in this study is based on a theoretical framework that brings together social learning, attachment, and feminist theory. In the remainder of this section, we discuss each of these theoretical frameworks in the light of the current literature and past empirical findings. Subsequently, we present the hypotheses that describe the proposed model.

Family-of-Origin Violence

Early studies on intimate partner violence attempted to understand violence by examining individual histories of batterers, with a view to identifying early childhood experiences that play a role in the onset and the continuation of violence (Babcock, Costa, Green, & Eckhardt, 2004). Research from this social-learning perspective commonly replicated the finding that many violent individuals have witnessed inter-parental aggression as children or have been the recipient of parental aggression (Caesar, 1988; Hotaling & Sugarman, 1986; Kalmuss, 1984; Murphy, Meyer, & O’Leary, 1994). Early work using social-learning perspective proposed that when children or youth observe violence between parents, they learn that violence is an acceptable or effective means for resolving conflicts with family members (Ehrensaft et al., 2003; Kalmuss, 1984; O’Leary, 1988). Critics argue that this explanation is not sufficient, because not everyone who has been abused or witnessed violence as a child becomes violent later in life (Jasinski, 2001). Indeed, according to Kaufman and Ziegler (1987), only 30% of individuals who witness violence during their childhood become violent. Consequently, supporters of this perspective have concluded that exposure to violence during childhood is an important risk factor that amplifies the risk of behaving violently as adults; however, it explains only a fraction of variability in violent behaviors.

Attachment

Early experiences of anxiety in insecure attachment relationships are associated with dysregulation of affect later in life (Keiley, 2002). Through interactions with their caregivers, infants learn what to expect from their caregivers and accordingly adjust their behaviors. The expectations about the availability and responsiveness of the caregiver form the basis of internal working models (Bretherton & Munholland, 1999). These internal working models, namely model of self and model of others, are transmitted to new relationships and they actively influence the perceptions and the behaviors of the individual in subsequent relationships. Model of self describes whether self is seen as worthy of love and support or not, whereas model of others describes whether others are seen as trustworthy and available or unreliable and rejecting (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991).

Studies investigating the association between attachment and relationship violence have found that, compared to men who are non-violent, men who are violent report significantly higher levels of relationship anxiety, fear of being abandoned in relationships, and more anxious attachment to their partners (Holzworth-Munroe, Stuart, & Hutchinson, 1997). In addition, many studies have demonstrated the link between attachment security and constructive communication skills that might lessen the use of violence in arguments (Feeney & Noller, 1996). Furthermore, during problem solving, secure individuals are less rejecting, more supportive, and inclined to rely on and trust each other more, as compared to insecure individuals (Kobak & Hazan, 1991). Attachment security was also found to be correlated to the degree and severity of violence; i.e., violent men who report more severe violence also report insecure attachment (Mikulincer, 1998). Overall, these findings indicate the importance of attachment as a factor in dating aggression. However, while attachment insecurity is linked to violence, it cannot provide a sufficient explanation since insecure attachments are far too common (Broussard, 1995) and most individuals who have insecure attachment patterns do not become violent at all.

Feminist Theories

Many feminist theories portray the patriarchal social system as justifying and condoning physical violence against women (Yllo & Straus, 1990). According to some of these perspectives, gender inequality in patriarchal social systems ensures that men have more resources available to them as compared to women (Smith, 1990). This imbalance in resources may manifest itself in submission of women in male-dominated families, or economic dependence of female partner on the male partner. Previous studies demonstrated that dependency and submission often add to dominance, which in turn contributes to intimate partner violence (Choi & Ting, 2008). Other research using power inequality perspective also indicated that imbalance of economic resources within a couple often is related to the use of violence (Fox, Benson, DeMaris, & Van Wyk, 2002). Fox et al. (2002) also found that women’s vulnerability to harm is higher when they live in a disadvantaged neighborhood and have a large number of children. Furthermore, research indicated that a more prevalent hostile-dominance pattern among men is associated with more severe intimate partner violence (Lawson, 2008). While most of these studies focus on the dominance of male batterers, recent research by Strauss (2008) found that dominance is associated with an increased probability of violence regardless of the gender of the partner.

Factors identified through social learning, attachment, and feminist theory perspectives are all individually correlated with the occurrence and severity of violence. However, each of these theories has limitations in explaining intimate violence. Consequently, if the factors identified by these theories are linked to different aspects of the onset and continuation of violence, they can account for each other’s limitations if they are considered together within an integrated framework. Motivated by these insights, we propose a comprehensive model that simultaneously incorporates factors derived from social learning theory (family-of-origin violence), attachment theory (internal working models of self and others, secure base representational knowledge, attachment anxiety, and avoidance), and feminist theory (egalitarian attitudes, power, and dominance) to explain intimate partner violence.

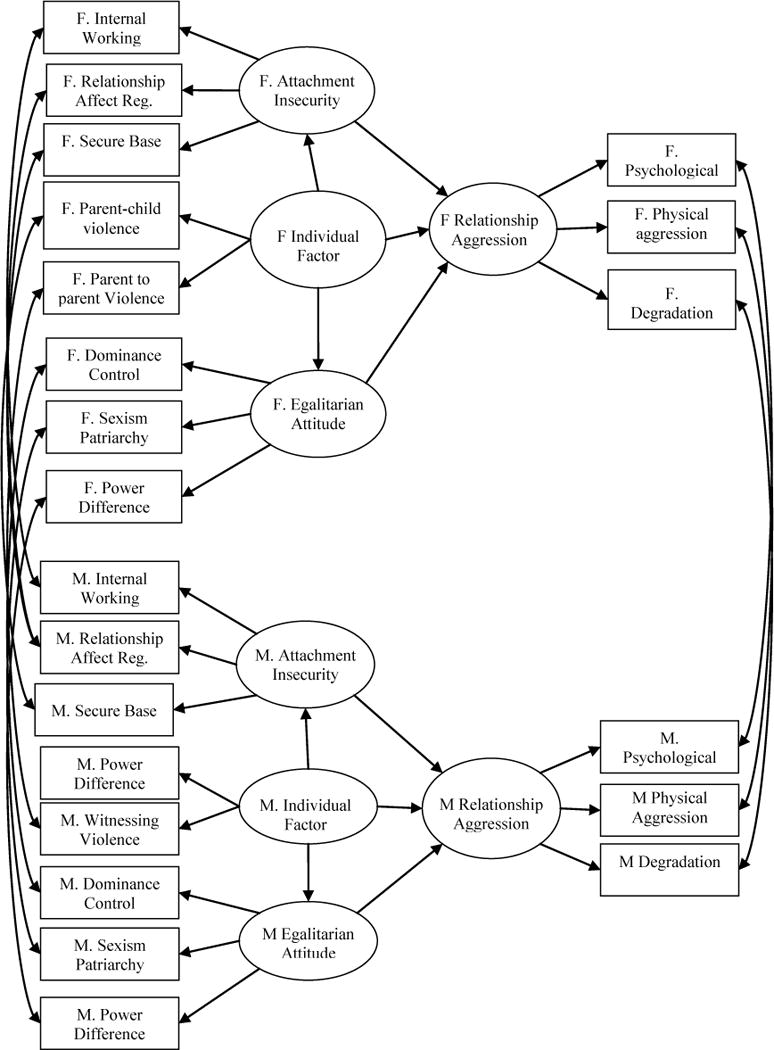

While there have been some recent studies on developing a multi-dimensional model to explain violence, most of these studies have investigated the interplay among multiple factors using only individual data that did not include the assessment of interactions between partners. The second aim of this study is to also capture the dyadic interactions that are associated with violence. A conceptual model that brings together social learning, attachment, and feminist perspectives within a dyadic framework is shown in Figure 1. In particular, the direct and indirect paths composing the hypothesized model are stated as individual hypotheses as follows:

Figure 1.

Conceptual model

H1: The existence of violent interactions between parents and/or aggression from parents to child during childhood will have a direct impact on adult attachment patterns.

H2: The existence of violent interactions between parents and/or aggression from parents to child during childhood will have a direct impact on egalitarian attitude formations.

H3: The existence of violent interactions between parents and/or aggression from parents to child during childhood will be directly and indirectly associated with later relationship violence via the intervening variables of attachment security and the couple interaction context (egalitarian or dominance based) for both men and women.

H4: Adult attachment patterns and egalitarian attitudes will be intervening variables between early childhood context and current violence from partner.

H5: Attachment security, including positive internal working models of self and others, as well as lower levels of attachment anxiety and avoidance, will be negatively associated with intimate violence.

H6: Egalitarian attitudes, such as the need for dominance/control, a large power discrepancy between partners, and a greater degree of sexism, will be significantly associated with intimate violence.

Method

Participants

This study was conducted with 87 heterosexual dyads. The average age of the participants in the sample was 22.3 years (SD = 4.80). The mean duration of dating was 32 months. Of the 87 dyads, 21% (n = 18) were dating for less than 6 months, 33% (n = 29) had a relationship with duration ranging from 6 to 20 months, and 46% (n = 40) had a relationship for more than 20 months. Most of the participants were European American (n = 102, 70 %), 9% (n = 13) were Asian, 8% (n = 11) were African American; 6% (n = 9) were Hispanic, 4% (n = 6) reported other ethnicities, and 3% (n = 4) did not report their race/ethnicity. Most participants were undergraduate students (86%, n = 125) at the time of the study and had some college education; 3% (n = 5) already had a Ph.D. degree, 3% (n = 4) had a master’s degree, some were non-students: 2% (n = 3) were high school graduates, and 6% (n = 8) did not report their education level.

Procedure

Participants were recruited through classroom announcements from a large Midwestern university. Interested participants contacted the investigator for answers to their questions and to arrange a time for participating in the study. After participants signed consent forms, they completed a battery of questionnaires about aggression, attachment patterns, gender role egalitarianism, dominance/control, sexism and aggression. Completing the questionnaires took between 60 to 90 minutes. After completion of the questionnaires, participants were asked to complete stories to assess their secure base representational knowledge. Four word-lists each containing a story outline were given to participants. These prompt words included familiar topics that were expected to elicit attachment themes. Participants’ verbal responses were audio taped; it took them about 20 to 30 minutes to complete. After story completion, participants were debriefed about the objectives of the study and if they were students they received extra credit for their participation. After that, participants were debriefed about the objectives of the study and if they were students they received extra credit for their participation.

Social Learning Theory Measures: Family-of-Origin Violence

Parent-to-child violence

Participants were asked to reflect on their entire childhood and report whether any occasions occurred in which their parents hit or were otherwise physically aggressive toward each other. Participants, who answered yes to any of this questions, were also asked to report the duration, intensity, and frequency of the occasions. Composite score is created by using this four questions. This method has been used in a number of studies to measure family of origin inter-parental violence (e.g., Cappell & Heiner, 1990; Kwong, Bartholomew, Henderson, & Trinkle, 2003).

Parent-to-parent violence

Participants were asked to consider their entire childhood and report whether any occasions ever occurred in which their parents hit or were otherwise physically aggressive toward them. Separate questions was asked for both mother and father. Participants, who answered yes to any of this questions, were also asked to report the duration, intensity, and frequency of the occasions. Composite score is created by using this eight questions. This method has been used in a number of studies to measure the family of origin violence (e.g., Cappell & Heiner, 1990; Kwong et al., 2003).

Adult Attachment Measures for Intimate Relationships

Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR; Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, 1998)

The ECR assesses two major dimensions; anxiety and avoidance, and consists of 36 items, 18 items for each dimension. Each item was rated on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (disagree strongly) to 7 (agree strongly). The alpha for the avoidance dimension has been reported as .94 and for the anxiety dimension .91 (Brennan et al., 1998). Higher scores on both scales reflect higher insecurity in close relationships. Construct validity of ECR has been confirmed in a wide variety of samples and in different languages (e.g., Mikulincer & Florian, 2000). Chronbach alpha was .91 for female anxiety and .88 for female avoidance and .91 for male anxiety and .93 for male avoidance.

Relationship Questionnaire (RQ; Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991)

The RQ assesses the profile of an individual’s attachment feelings and behaviors. It includes four short paragraphs, each describing Bartholomew’s four-attachment prototypes (secure, preoccupied, fearful and dismissing). On a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (disagree strongly) to 7 (agree strongly), participants were asked to rate their degree of correspondence with each paragraph and then select one of the paragraphs that described them best. Moderate test-retest reliability of the measure for over 8 months period was demonstrated (r=.70) (Scharfe & Bartholomew, 1994). It has also been demonstrated that the RQ has satisfactory construct validity (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991). The RQ was used to derive underlying attachment dimensions. In order to compute the score for mental model of self, the sum of each individual score on the secure and dismissing items was subtracted from the sum of each individual score on the fearful and preoccupied items. The score for mental model of others was computed by subtracting the sum of the individual scores on the fearful and dismissing items from the sum of individual scores on the secure and preoccupied items.

Emotion Regulation Checklist (ERC; Shields & Cicchetti, 1997)

The ERC is a 24-item scale. It includes both positively and negatively weighted items rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1= “Never” and 4 = “Always”). Alpha for the emotion regulation scale has been reported as .96 (Shields & Cicchetti, 1997). External validity of this scale was confirmed in a previous study (Ramsden & Hubbard, 2002). In the current study, the Chronbach alphas were .71 for females and .68 for males. The 24 items were summed and then divided by 24 to create an average scale score of emotion regulation —higher scores meant better emotion regulation and vice versa.

Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations (CISS; Endler & Parker 1990)

This 48 item measure was designed to measure three main coping strategies: task focused, emotion focused, and avoidance focused. These three coping strategies are strongly linked with affect and emotion regulation and thus have often been used to measure that construct (Keiley, 2002). Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1= “not at all” to 5= “very much.” Reliability of the scale ranges from .82 to .90 (Cosway, Endler, Sadler, & Deary, 2000). Moreover, test-retest reliability of the scale ranges from .60 to .70 over a period of six weeks (Endler & Parker, 1990). Higher scores on each scale show greater usage of the coping strategy being tapped. In this study, the scores for three coping strategies that were significantly correlated with each other were combined into one global score for coping with stressful situations. In the current study Cronbach alpha was .83 for females and .82 for males.

Secure base scriptedness

In order to assess secure base representational knowledge, participants were asked to provide stories about relationships. Participants were presented with four sets of prompt words to guide their stories. The four story outlines that were given to participants involved either romantic partners or mother and child/baby dyads. Two stories were about adult relationships: “Jane and Bob’s camping trip,” and “The accident.” Mother-child stories were titled “Baby’s morning” and “The doctor’s office.” Scoring procedures included both content elaboration and prototypic scriptedness of the narratives provided ranging from 1 (no secure base script) to 7 (secure base script) (Coppola, Vaughn, Cassibba, & Costantini, 2006; Vaughn et al., 2006). The script-based approach to study the organization of knowledge about attachment relationships was initially presented by Waters, Rodrigues, and Ridgeway (1998). Validity of this approach has been demonstrated elsewhere (Coppola et al., 2006; Vaughn et al., 2006). For secure base scripts, principal component analysis indicated that all items loaded on one factor. For female participants, this factor contained 52% of the total variance (eigenvalue=2.08), with an alpha of .69. For male participants, this scale contained 55% of the total variance (eigenvalue=2.23), with an alpha of .72. Cohen Kappa for inter-rater reliability between two raters who scored the stories was .80.

Feminist Theory / Egalitarian Attitude Measures

Dominance Scale (DS; Hamby, 1996)

The DS was developed to measure three dimensions of dominance toward an intimate partner (authority, restrictiveness, and disparagement). It includes 32 items rated on a 4-point Likert Scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” (1= “Strongly Disagree,” 2=“Disagree,” 3=“Agree,” and 4=“Strongly Agree”). Reliability of the three subscales ranges from .73 to .82. Initial construct validity of the scale has also been found to be satisfactory (Hamby, 1996). In this study, the scores on three dimensions of dominance were combined into an overall dominance score. Higher scores indicated the need for higher dominance in the relationship. In the current study, the alphas for the full scale were .90 for females and .88 for males.

The Sexual Relationship Power Scale (Pulerwitz, Gortmaker, & DeJong, 2000)

Five items of the Sexual Relationship Power Scale (Pulerwitz, 2000) were selected particularly due to focus on providing a theoretically grounded, culture based, and measurable definition of power difference. Participants rated the items based on a 7 point Likert scale ranging from 1 (disagree strongly) to 7 (agree strongly), This scale is based on the structural theory of gender and power, and exchange theory orientation of relationship power. In the current study, the alphas for this scale were .90 for females and .88 for males.

Sex Role Egalitarianism Scale (SRES; Beere, King, Beere, & King, 1984)

The SRES assesses the attitudes toward the equality of men and women. In this study, SRES-Short Form was used. This shorter version of the SRES consists of 25 items. For each of the five SRES domains equal representations of five items were selected from the original general sex role egalitarianism measure. The five subscales include educational roles, employment roles, marital roles, parental roles, and social-interpersonal-heterosexual roles. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale rating from 1=“strongly disagree” to 5=“strongly agree”. Cronbach’s alpha for each scale ranges from .97 to 87. Test-retest reliability over a 4-week period is .85 over the domains (Beere et al., 1984). Convergent and discriminant validity have been established (e.g., Beere et al., 1984). This scale has been widely used (e.g., Belitsky, Toner, Ali, & Yu, 1996; Crossman, Stith, & Bender, 1990). In the current study, the alphas for the whole scale were .86 for females and .92 for males. In this study, the scores on the five SRES domains were combined into a global score for Sex Role Egalitarianism, with higher scores indicating higher values on sex role egalitarianism.

The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (ASI; Glick & Fiske, 1996)

The ASI is a 22-item measure that was developed to measure sexist attitudes. The ASI has two 11-item subscales; benevolent and hostile sexism. Items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1= “strongly disagree” to 5= “strongly agree”. These subscales have a previously reported reliability between .80 and .94 (Glick & Fiske, 1996). In the current study, for female participants the alpha was .79 while the alpha for male participants was .78. In this study, an overall sexism score was created by using the whole scale, where higher scores indicated more sexism.

Relationship Aggression Measures

Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996)

The CTS2 has 78 items. In particular, four subscales of this measure were used to assess how college students managed disagreements with their dating partners ranging from never happened to more than 20 times (0= never happened in the last 4 months, 1= “Once,” 2= “Twice,”, 3 = “3–6 times,” “4 = 7–10 times, ” “5= ”11–20 times, “ 6 = ”More than 20 times”). For the CTS2, reliability ranges from .62 to .88 for verbal aggression and from .79 to .88 for physical aggression. It is a widely used instrument with good construct validity (Archer, 1999). In the current study, the reliabilities for female participants’ reports of their partners’ conflict tactics on the four subscales were .80 for psychological aggression, .77 for physical assault, .70 for sexual coercion, and .53 for injury. The reliabilities for male participants’ reports of their partners’ conflict tactics on the four subscales were .69 for psychological aggression, .79 for physical assault, .69 for sexual coercion, and .51 for injury. Due to low reliability and zero variance, items in the injury subscales were not included in the analysis. Instead intimate partner violence for this study was measured by the psychological aggression, physical assault, and sexual coercion subscales using Strauss’ (2004b) scoring procedures for creating frequency scores. Higher scores indicated higher interpersonal violence.

Emotional Abuse Questionnaire (EAQ; Jacobson & Gottman 1998)

The EAQ has 66 items assessing verbal and sexual abuse and threatening behavior, each rated on a 4-point frequency scale (1=“Never” to 4=“Very Often”). The EAQ has four subscales, which were theoretically derived: isolation, degradation, sexual abuse, and property damage. In the EAQ, participants report on their partners’ behavior rather than their own behaviors. Internal consistencies for subscales have been shown to be .92, .94, .72, and .82, respectively (Jacobson & Gottman 1998). In the current study, for female participants, internal consistency for the four subscales was α=.74 for isolation, α=.67 for degradation, α=.35 for sexual abuse, and α=.31 for property damage. For male participants, internal consistency for the four subscales was α=.91 for isolation, α=.92 for degradation, α=.89 for sexual abuse, and α=.60 for property damage. Due to low reliability of sexual abuse and property damage, particularly for female participants, these two subscales were not used to measure aggression in the analysis for either males or females. A composite score for isolation and degradation was created and used in analyses, where higher scores are indicative of greater degrees of isolation and degradation.

Data Analysis

Most statistical methods are based on the assumption of independence. Violation of this assumption leads to serious biases in estimation of standard errors (Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002). Kenny, Kashy, and Cook (2006) suggest that Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) has become one of the most powerful tools for answering complex questions with dyadic data. Therefore, in this study, the proposed model was tested with SEM. Full-information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML) was used in AMOS 17, a Structural Equation Modeling software solution developed by SPSS. It uses all available data for parameter estimation under the assumption that data are missing at random. Since the number of parameters (paths) in the model requires a relatively large number of parameters, this may adversely affect statistical power. To alleviate this problem, we used bootstrapping (Schafer & Graham, 2002). Furthermore, since degree of freedom increases with multiple data-points per person, we were able to estimate more paths for the couple level. To further enhance statistical power, we reduced model complexity by merging latent variables rather than using each subscale in the model. The proposed model was tested in two steps. In the first step, several measurement models were tested via confirmatory factor analysis, in order to examine how well the indicators served as measurement instruments for latent variables. In the second step, structural models including the hypothesized model were tested.

Several methods exist for evaluating how well a proposed model fits the data. In this study, the ratio of the estimated χ2 to degrees of freedom was used to test how well a model reproduced the sample data as suggested in several studies (Carmines & McIver, 1981; Wheaton, Muthen, Alwin, & Summers, 1977). Smaller values of χ2 indicate a better fit so nonsignificant χ2 values are desired. The ratio χ2: df of 2:1 to 5:1 is suggested as acceptable (Marsh & Hocevar, 1988; Singer & Willet, 2003).

Results

Variables included in the analysis were examined to assess the accuracy and completeness of the data. In order to ensure that the data were normally distributed Shapiro-Wilk test for normality was estimated. Results indicated that female and male dominance, physical assault frequency, sexual coercion frequency, psychological aggression, isolation and degradation variables indicated a slight positively skewed distribution with unsatisfactory normality. In order to avoid violating the normality assumptions these variables were transformed. The necessary transformation was carried out by taking the natural logarithm of the variables. After transformation dominance were normally distributed, while the distributions of physical assault frequency, sexual coercion frequency, psychological aggression, isolation and degradation were considerably closer to normal.

Means, standard deviations, ranges, reliabilities and corresponding group t-tests for gender differences in attachment model of self, attachment model of others, attachment anxiety and avoidance, egalitarianism, sexism, and violence variables are shown in Table 1. The correlations between major variables are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Reliabilities for the Major Variables

| Female | Male | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | Alpha | Range | Alpha | |||||

| Mean | S.D | Mean | S.D | |||||

| Witnessing Violence: | ||||||||

| Parent to child violence | .21 | .41 | 0–1 | .32 | .47 | 0–1 | ||

| Parent to parent violence | .26 | .44 | 0–1 | .27 | .45 | 0–1 | ||

| Egalitarian Attitude: | ||||||||

| Dominance | 1.04 | .12 | 1.28–3.50 | .90 | 1.07 | .13 | 1.25–3.41 | .80 |

| Power differences | 3.57 | .57 | 2.18–5.29 | .90 | 3.51 | .61 | 1.45–3.59 | .88 |

| Sexism | 2.73 | .46 | 1.55–3.55 | .79 | 2.87 | .46 | 2.29–5.24 | .78 |

| Egalitarianism | 4.20 | .72 | 1.48–6.28 | .86 | 3.94 | .76 | 1.64–5.00 | .92 |

| Attachment security: | ||||||||

| Attachment Insecurity | 2.48 | .82 | .97–4.39 | .90 | 2.34 | .82 | 1–4.58 | .92 |

| Model of Self | 2.03 | 4.39 | (−8)−10 | 3.27 | 3.31 | (−5)−10 | ||

| Model of Others | .03 | 4.10 | 10−(−8) | .79 | 4.31 | (−9)−8 | ||

| Affect Regulation | ||||||||

| Coping Stress Situations | 3.35 | .40 | 2.65–4.31 | .83 | 3.12 | .37 | 2.17–3.90 | .82 |

| Emotion Regulation | 1.13 | .09 | 1.63–3.17 | .71 | 1.13 | .08 | 1.58–2.88 | .68 |

| Attachment Narratives | ||||||||

| Secure Base Knowledge Knowledge | 3.80 | 1.23 | 1.25–6.75 | .69 | 3.21 | 1.00 | 1.5–6 | .72 |

| Relationship Aggression: | ||||||||

| Psychological aggression | 1.77 | 1.20 | 0–55 | .80 | 1.72 | 1.25 | 0–45 | .69 |

| Physical Assault | .69 | 1.03 | 0–30 | .77 | .43 | .81 | 0–30 | .79 |

| Sexual Coercion | .72 | 1.64 | 0–52 | .70 | .24 | .74 | 0–28 | .69 |

| Isolation | 3.42 | .21 | 24–75 | .53 | 3.56 | .26 | 24–81 | .51 |

| Degradation | 3.47 | .13 | 28–52 | 3.57 | .24 | 28–81 | ||

p<.05

p<.01

Table 2.

Correlations Among Major Variables

| Attachment Insecurity Female | Attachment Insecurity Male | Model of Self Female | Model of Others Female | Model of Self Male | Model of Others Male | Secure Base Female | Secure Base Male | Coping Female | Coping Male | Emotion Regulation Female | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attachment Insecurity Female | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| Attachment Insecurity Male | 0.19 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Model of Self Female | −0.42 | −0.03 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Model of Others Female | −0.32* | −0.16 | 0.34** | 1.00 | |||||||

| Model of Self Male | 0.00 | −0.42** | −0.03 | 0.08 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Model of Others Male | −0.03 | −0.27* | −0.20 | −0.03 | −0.08 | 1.00 | |||||

| Secure Base Female | −0.22* | −0.20 | 0.10 | 0.18 | −0.10 | 0.10 | 1.00 | ||||

| Secure Base Male | −0.03 | −0.09 | −0.06 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 1.00 | |||

| Coping Female | 0.30** | 0.27* | −0.08 | 0.00 | −0.02 | −0.15 | −0.21 | −0.16 | 1.00 | ||

| Coping Male | 0.16 | 0.46** | −0.24 | −0.15 | −0.20 | −0.16 | −0.17 | −0.13 | 0.19 | 1.00 | |

| Emotion Regulation Female | 0.43** | 0.35** | −0.12 | −0.18 | −0.07 | 0.07 | −0.20 | 0.04 | 0.43** | 0.09 | 1.00 |

| Emotion Regulation Male | 0.23 | 0.36** | 0.05 | −0.08 | −0.16 | −0.19 | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.24 | 0.05 |

| Dominance Female | 0.44** | 0.24 | −0.28* | −0.17 | −0.29* | −0.11 | −0.05 | −0.20 | 0.18 | 0.05 | 0.31** |

| Dominance Male | 0.03 | 0.37** | 0.05 | 0.02 | −0.18 | −0.14 | 0.05 | 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.20 | 0.06 |

| Egalitarianism Female | −0.02 | −0.09 | 0.22* | 0.00 | 0.19 | −0.05 | −0.14 | −0.11 | 0.14 | −0.02 | −0.01 |

| Egalitarianism Male | 0.04 | −.27* | −0.12 | −0.16 | 0.11 | 0.08 | −0.13 | 0.11 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.05 |

| Sexism Female | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.11 | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.08 |

| Sexism Male | 0.10 | 0.29* | −0.21 | −0.11 | 0.03 | 0.13 | −0.16 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.18 | −0.16 |

| Parent Child Violence Female | −0.01 | 0.25 | −0.02 | 0.13 | −0.23 | −0.06 | −0.07 | −0.28* | 0.12 | 0.25 | −0.04 |

| Parental Conflict Female | 0.09 | 0.19 | −0.11 | −0.02 | −0.21 | −0.10 | −0.08 | 0.00 | −0.13 | −0.07 | −0.09 |

| Parent Child Violence Male | 0.15 | −0.12 | −0.14 | −0.20 | −0.07 | 0.09 | −0.09 | −0.02 | −0.13 | 0.06 | −0.05 |

| Parental Conflict Male | 0.17 | 0.19 | −0.08 | −0.17 | −0.26 | 0.11 | −0.07 | 0.08 | −0.13 | 0.11 | 0.19 |

| Isolation Female | 0.36** | 0.25 | −0.12 | −.245* | −0.13 | −0.08 | −0.10 | −0.06 | .308** | 0.14 | 0.18 |

| Isolation Male | −0.17 | .299* | 0.09 | 0.08 | −0.01 | −0.13 | 0.00 | −0.08 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| Degradation Female | .518** | .270* | −.239* | −.311** | −0.06 | −0.11 | −0.21 | −0.02 | .224* | 0.10 | 0.16 |

| Degradation Male | −0.05 | .441** | 0.11 | −0.06 | −0.08 | −0.07 | 0.04 | −0.05 | −0.07 | 0.10 | 0.03 |

| Psychological Agression Female | .309* | .427** | −.286* | −.376** | 0.02 | −0.12 | −0.18 | 0.05 | 0.22 | 0.05 | .551** |

| Psychological Agression Male | 0.22 | .398** | −0.19 | −.338* | −0.01 | −.292* | −0.20 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.18 |

| Physical Assault Female | 0.03 | .387** | 0.00 | −.406** | 0.10 | −0.11 | −0.21 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.23 |

| Physical Assault Male | 0.05 | 0.23 | −0.08 | −.364** | −0.02 | −0.19 | −0.15 | −0.19 | 0.06 | 0.26 | −0.09 |

| Sexual Coercion Female | 0.02 | 0.15 | −0.16 | −.281* | 0.16 | −0.21 | −0.04 | −0.07 | −0.02 | −0.04 | 0.16 |

| Sexual Coercion Male | −0.07 | 0.19 | −0.23 | −0.11 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.10 | −0.23 | −0.07 | 0.14 | 0.12 |

| Emotion Regulation Male | Dominance Female | Dominance Male | Egalitarianism Female | Egalitarianism Male | Sexism Female | Sexism Male | Parent Child Violence Female | Parental Conflict Female | Parent Child Violence Male | Parental Conflict Male | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotion Regulation Male | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| Dominance Female | 0.10 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Dominance Male | 0.28* | 0.10 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Egalitarianism Female | 0.09 | −.54** | −0.38** | 1.00 | |||||||

| Egalitarianism Male | −0.12 | −0.14 | −0.74** | .441** | 1.00 | ||||||

| Sexism Female | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.19 | −.541** | −.363** | 1.00 | |||||

| Sexism Male | 0.00 | −0.05 | .307* | −.301* | −.461** | .429** | 1.00 | ||||

| Parent Child Violence Female | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.22 | 0.06 | −0.18 | −.266* | 0.03 | 1.00 | |||

| Parental Conflict Female | 0.11 | 0.22* | 0.03 | −0.19 | −0.10 | −0.05 | −0.16 | .273* | 1.00 | ||

| Parent Child Violence Male | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.33* | −0.14 | −0.16 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Parental Conflict Male | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.20 | −.335* | −0.15 | .323* | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.06 | .302* | 1.00 |

| Isolation Female | .339* | .436** | .346* | −.326** | −0.17 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.17 |

| Isolation Male | 0.17 | .335* | .357* | −.295* | −0.24 | −0.07 | .287* | 0.15 | 0.21 | −0.10 | −0.24 |

| Degradation Female | .387** | .538** | 0.05 | −0.17 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.03 | .310** | −0.01 | .400** |

| Degradation Male | .447** | 0.17 | .464** | −0.14 | −0.25 | −0.02 | 0.24 | 0.12 | .276* | 0.00 | −0.01 |

| Psychological Agression Female | 0.11 | .415** | 0.19 | −0.09 | −0.07 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.26 | 0.15 | −0.01 | 0.10 |

| Psychological Agression Male | 0.26 | .331* | 0.21 | −0.06 | −0.07 | −0.25 | −0.08 | .328* | .410** | 0.19 | 0.13 |

| Physical Assault Female | 0.21 | 0.25 | .339* | −0.09 | −0.08 | −0.19 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.01 |

| Physical Assault Male | 0.20 | .346* | 0.23 | −0.09 | −0.18 | −0.28 | −0.03 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.09 |

| Sexual Coercion Female | −0.12 | 0.24 | 0.15 | 0.10 | −0.02 | −0.10 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.19 |

| Sexual Coercion Male | −0.07 | 0.11 | 0.11 | −0.03 | −0.13 | 0.12 | 0.08 | .392** | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.16 |

| Isolation Female | Isolation Male | Degradation Female | Degradation Male | Psychological Agression Female | Psychological Agression Male | Physical Assault Female | Physical Assault Male | Sexual Coercion Female | Sexual Coercion Male | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation Female | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Isolation Male | 0.15 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Degradation Female | .577** | 0.06 | 1.00 | |||||||

| Degradation Male | 0.21 | .665** | 0.23 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Psychological Agression Female | .349* | 0.22 | .294* | .392** | 1.00 | |||||

| Psychological Agression Male | .498** | 0.26 | .519** | .382** | .747** | 1.00 | ||||

| Physical Assault Female | .515** | .483** | .316* | .657** | .633** | .624** | 1.00 | |||

| Physical Assault Male | .442** | 0.20 | .479** | .370** | .308* | .527** | .528** | 1.00 | ||

| Sexual Coercion Female | 0.14 | .459** | 0.14 | .386** | .498** | .334* | .487** | 0.13 | 1.00 | |

| Sexual Coercion Male | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.15 | .515** | .352** | 0.21 | 0.14 | .497** | 1.00 |

Measurement Model

In order to understand whether the latent variables of (attachment/attachment security, egalitarian/feminist attitude, relationship aggression, family of origin factors are significantly associated with the corresponding observed variables, a series of confirmatory factor analyses were conducted. Prior to fitting the proposed SEM, measurement models with the latent factors (attachment/attachment security, egalitarian/feminist attitude, and relationship aggression) and observed variables (social learning factors) were fit to the data from the 87 dyads. Results indicated satisfactory fit to the measurement models except than family of origin violence latent variable, giving the permission to test the hypothesized model. Measurement models with family of origin violence indicators indicated a non-satisfactory model fit for both males and females; the model was estimated as an unidentified model. Therefore, rather than continuing to use a latent variable structure for this construct, indicators of parent to parent conflict and parent to child aggression were used directly in the model for both males and females.

Hypothesized Model

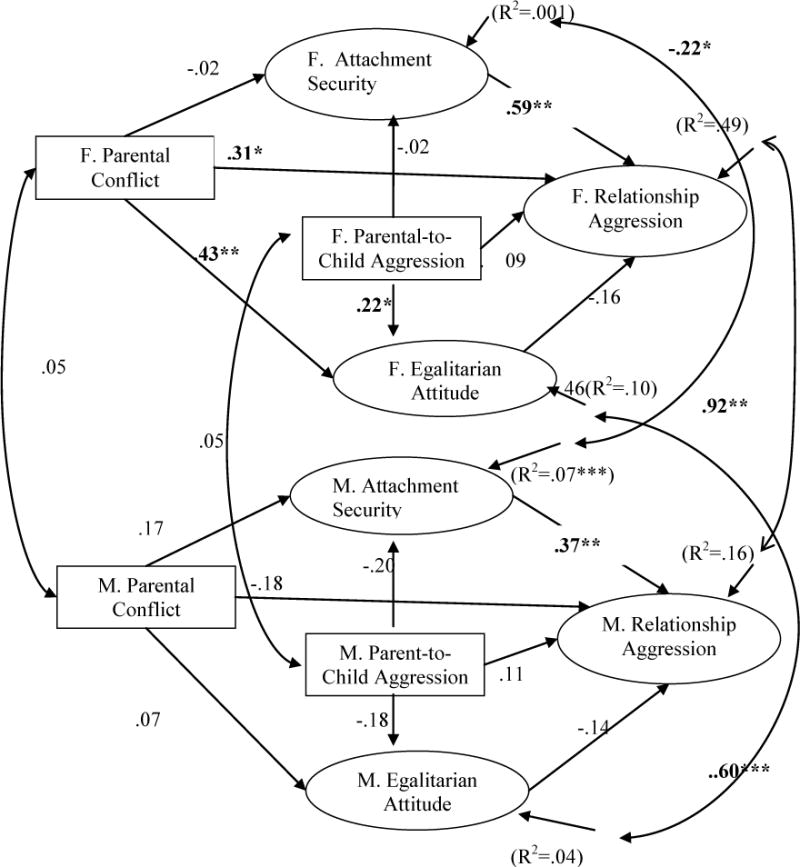

Measurement models (except than family of origin) demonstrated that latent variables were successfully related to the observed variables. We then tested the hypothesized model. Findings indicated that the proposed model provided a good fit to the data (χ2(333, N=87) = 616.89, p < .00) in that the ratio of χ2 statistics to the df was 1.85. Results for the non-standardized coefficients with estimated correlations are shown in the Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Fitted model with standardized coefficients (*p<.05, **p< .01, ***p<.001). Please note that F. stands for the female partners and M. stands for the male partners.

In particular, we expected that witnessing violence during childhood would have a direct effect on relationship aggression (H3). Our results indicated partial support to this hypothesis, in that female parental conflict had significant direct effect on the female relationship aggression (β =.06, r =31, p < .05). On the other hand, female-reported parent-to-child aggression did not have any significant direct effect on female relationship aggression (β = 02, p > .05). Results also showed that male-reported parental conflict had a marginally significant direct effect on male relationship aggression (β =−06, r = −.18, p < .09) but parent-to-child aggression did not (β= .04, p>.05).

We also hypothesized (H5) that attachment insecurity, would have a direct effect on relationship aggression. We found that the female attachment insecurity factor had a significant direct effect on female relationship aggression (β =.09, r = 59, p < .001). Similarly, the male attachment insecurity factor had a significant direct effect on male relationship aggression (β =.07, r = .37, p < .01).

Finally, we hypothesized (H2) that the early childhood context would have an impact on egalitarian attitude formations. Examination of the structural path parameters showed that, female-reported parental conflict had a significant direct effect on the female Egalitarian Attitude factor (β =.21, r =.43, p < .01). Similarly, results indicated that female-reported parent to child aggression had a significant direct effect on the female egalitarian attitude factor (β = −35, r = −.22, p < .05). Neither parent-to-parent aggression (β = .11, p>.05) or parent-to-child aggression (β = −26, p>.05) early in life had an effect on male Egalitarian Attitude. In addition, in contrast to our expectation, the egalitarian attitude factors for males and females, such as need for dominance, low value of egalitarianism, and a greater value placed on sexism, had no direct effect on relationship aggression when all else was controlled in the model (βfemale = −.02, p>.05; βmale = −.03, p>.05).

Results did not support any of the indirect effects that we were expecting (H1 and H4), such as, witnessing violence during childhood was not indirectly related to later relationship aggression via the intervening variables of the egalitarian attitude and attachment security for both men and women. Parental-to-parent and parent-to-child aggression, taken together, only predicted 0.1% of the variance of female attachment insecurity; for male attachment insecurity, 7% of the variance was predicted by the same two early parental aggression measures. On the other hand, the inter-parental and parent-to-child aggression variables predicted 10% of the variance of female egalitarian attitudes and 4% of male attitudes. Despite some low levels of variance being explained in the intervening constructs, this model accounted for a large amount of variance (49%) in females’ being subjected to relationship aggression and a moderate amount of variance (16%) in males’ being subjected to relationship aggression.

Discussion

While previous studies have concentrated on the different factors that might be related to violence, more comprehensive models that incorporate multiple factors together have been suggested as necessary. The present study aimed to understand the potential links and pathways of intimate partner aggression in a multi-dimensional theoretical framework. In particular, it was hypothesized that the existence of violent interaction between parents and/or aggression from parents to child during childhood would directly and indirectly be related to relationship aggression via attachment insecurity (internal working models, relational affect regulation strategies, and secure base) and egalitarian attitude formations (power differences, sexism, and dominance) for both men and women. Findings of the study indicated partial support for this hypothesis. Specifically, witnessing parental conflict during childhood had significant positive direct effect on women’s being abused by their partners. Results indicated that women who witnessed parental conflict during their childhood were more likely to be victimized by their current romantic partner. It is possible that parents who display conflict and hostile negative interactions with each other may model unregulated behavior for their children (Eisenberg et al., 2001). However, this effect was observed only for females, but not for males. This result might also suggest that role modeling is facilitated by gender identification (Bandura & Walters, 1959). Therefore, it is probable that females are more likely to identify with the parent who experienced aggression from their spouse. This would make more sense when it is considered that females are often discouraged to act aggressively by society.

In previous studies, frequent harsh parenting with physical threats, aggression, and punitive behaviors were found to be negatively associated with the ability of children to regulate their emotions (Eisenberg et al., 1999). Furthermore, physically and emotionally aggressive parenting has been linked to children’s emotion regulation capacity that forms the basis for children’s interactions with others (Sroufe & Fleeson, 1986). Therefore, we anticipated that parent to child aggression would be related to the experience of relationship aggression. However, our results did not support this hypothesis in the context of our model. Moreover, no indirect effect of parental conflict and parental violence was observed on relationship aggression toward participants. The lack of this path might be partly due to the perception of parental aggression as disciplining. It was hypothesized that attachment insecurity including positive internal working models of the self and others, functional models of affect regulation behaviors, and secure base scripts, will be negatively associated with relationship aggression, controlling for all else in the model. This hypothesis was fully supported by the finding that being in a dysfunctional relationship (having insecure attachment and poor affect regulation) had a significant direct positive effect on participants’ experiences of aggression in their current relationships, for both female and male participants. This finding suggests that, regardless of gender, participants who are not securely attached to their partners and have difficulty regulating emotion are also more likely to be victimized by their partners in their relationships. Experiences with attachment figures do function to determine individual differences in children’s affective, behavioral, and cognitive responses (Shaver & Hazan, 1994). For instance, secure attachment relationships between parents and children are associated with positive outcomes for children such as being competent, handling conflict efficiently, performing better cognitively, having higher self-esteem, having better communication skills, being involved in healthy friendships, and having more satisfying romantic relationships in later years (Shaver & Hazan, 1994). For secure individuals, emotional, cognitive and behavioral skills, such as the ability to cope with stress, accurately interpret social cues, and problem solving skills, are positively related to the development of smoothly working attachment relationships (Frankle, 2000). These smoothly working attachment relationships were found to play a protective role against violent outbursts (Frankle, 2000) as was found in the current study.

We also hypothesized that egalitarian attitude in the relationship context, such as the need for dominance/control, discrepancy of power differences between partners, and the value placed on sexism, will be related to relationship aggression, controlling for all else in the model. Contrary to our expectation, no direct effect was observed between having an egalitarian attitude and relationship violence for either male or female participants. Previous studies have indicated inconsistent findings regarding intimate partner violence as a by-product of patriarchy, dominance, and power advantages (Dutton & Nicholls, 2005). For example, some studies indicated females could be as abusive as males (Stets & Straus, 1992). Similarly, some other studies have showed that across the US, cultural pointers of patriarchy were not associated with male-to-female violence (Yllo & Straus, 1990). According to Dutton and Nicholls (2005), relationship violence is generated by intimacy and psychopathology rather than gender. It appears from our analysis that, for both sexes, sexism, egalitarianism, and dominance have less explanatory power than attachment security, secure base representations, and affect regulation strategies for being subjected to violence from their partner in dating relationships in a sample of college students.

The first wave of relationship aggression research was mainly focused on male to female violence, while recent research has focused, as well, on women to men relationship aggression (Archer, 2000; Capaldi, Kim, & Shortt, 2007). One aim of this study was to examine the path to intimate relationship aggression for both partners. Results indicated that our model accounted for a large amount of variance (49%) for females being subjected to aggression from their partners, while it accounted for a smaller amount of variance (16%) for males’ being subjected to aggression from their partners. These data suggest that when family-of-origin violence, egalitarian attitude, and relationship factors such as functional affect regulation and attachment security are all controlled, we explain more variation in male to female relationship aggression, as reported by female participants than in female to male aggression, as reported by males. Perhaps female-to-male aggression has different correlates, compared to male-to-female aggression. The gender differential in the ability of our predictors to explain variance might also be due to differences in the tendency to report aggression. Current research indicates that men are less likely than are women to identify physical and sexual abuse perpetrated on them (Nabors, Dietz, & Jasinski, 2006). Furthermore, males are found to have a tendency to report aggression in their relationships only if they have been sexually abused as children (Prospero, 2007). However, more research is needed to understand female-to-male aggression in intimate relationships, especially considering the different risk factors associated with it.

According to Johnson (1995), less severe violence is related to commonly occurring couple conflict and mutual physical aggression between partners. On the other hand, more severe forms of violence that lead to injury as reported by women in domestic violence shelters are predominantly one sided in male-to-female violence. Accumulative evidence also suggests that mutual couple violence is less severe and more common than severe male to female violence (e.g., intimate partner terrorism) (Capaldi, Shortt, & Crosby, 2003; Cascardi, Langhinrichsen, & Vivian, 1992). Although the current study included psychological and sexual aggression as well as less severe forms of violence, our results were consistent with literature in terms of common couple violence. Findings indicated that male and female relationship aggression were significantly and highly positively correlated (r = .92) when all else was controlled. This finding suggests that when females report higher levels of experiencing aggression, their partners are also likely to report higher levels of being subjected to aggression.

While interpreting the results of this study, one should also recognize the fact that data collected primarily from college students allow only limited generalization. This study mainly focused on college students who were currently in a romantic relationship. However, married couples, or couples who are older might have different relationships. Therefore, it is important to extend this study by collecting additional data that spans a broader range of participants, in terms of age and socio-economic status. Thus, although provocative, the results presented can only be considered initial. Another limitation of this study is that family-of-origin violence (parent-to-parent and parent-to-child) was assessed through single items. Use of single-item measures to assess complex constructs like family-of-origin violence can be limiting.

Our model accounted for much less of the variance for female-to-male aggression (% 16) as compared to male-to-female aggression (% 49). However, effect size in social sciences is heavily dependent on measurement, design, and method. Moreover, effect sizes in social research suffer from the measurement errors which happen whenever anything is scaled (McCartney & Rosental, 2000). Despite the differences in effect sizes reported, it is important to note that small effect sizes should not be dismissed out of hand. Here it is to bring up findings of a randomized double-blind experiment on the effects of aspirin in reducing heart attacks (Steering Committee of the Physicians’ Healthy Study Research Group, 1988) indicated a small effect size (r =.03) by conventional means. However, when the number of people affected from heart attacks is considered, the value of this finding becomes more apparent, providing an excellent example for a situation in which a small effect size translates into great practical importance. Similarly, although this study accounts for 16% of variance in female-to-male variance, considering the importance of and the devastating consequences of relationship violence, the value of the information provided by this model becomes more apparent.

One strength of this study is that it concentrated on dyadic patterns of relationship violence in understanding the interactions in which violent behaviors emerge. Couples participated in the study together and this improved our understanding of the path to violence at the individual, as well as the couple level. Since the proposed model was dyadic and included a broad range of factors, we were able to identify the gender differences in terms of not only the experience of violence, but also the adequacy of the model (and the factors considered thereof). In particular, dyadic analysis revealed that witnessing parental conflict during childhood appears to have a different influence on males and females. While witnessing parental conflict had positive direct relationship with aggression against females, we did not observe any relationship between males’ witnessing parental conflict and relationship aggression against males. Furthermore, we did not explain as much variance as we expected in our interventing constructs of attachment insecurity for the females but more was explained for the males. In other words, family-of-origin violence (both observed and experienced) has higher impact on attachment insecurity for males than for females. However, this was not the case for egalitarian attitudes. We explained more variance in egalitarian attitudes (measured in terms of sexism, dominance, and egalitarianism) for females who observed and experienced family-of-origin violence than for males.

Another strength of the study was its multidimensional approach to examining the paths to relationship aggression. This multidimensional approach helped us understand the interplay between variables in their association with relationship aggression. When considered independently, witnessing violence during childhood, attachment security, and egalitarian attitude within the relationship were found to be significant contributors for intimate partner violence. Finally, while similar multidimensional conceptualizations were used in explaining intimate partner violence recently, they were generally limited to theoretical conceptualizations (Bell & Naugle, 2008; Finkel, 2007). By collecting dyadic data and analyzing it through structural equation modeling, this study made an attempt to provide a quantitative base for such theories.

In conclusion, relationship aggression is an important social problem all over the world. Yet, there is more to be done to educate the public about its influences, its reasons, and ways out of it. This study provides an initial step towards a comprehensive understanding of intimate relationship violence, showing that for both genders, attachment insecurity are crucial factors in the manifestation of relationship aggression. Findings presented could be used in helping clinicians to develop effective intervention methods while working with couples.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by the Kappa Omicron Nu Honor Society with funding from the Kappa Omicron Nu National Research Fellowship. This publication was also made possible in part by the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland, UL1TR000439 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) component of the National Institutes of Health and NIH roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Contributor Information

Günnur Karakurt, Case Western Reserve University.

Margaret Keiley, Auburn University.

German Posada, Purdue University.

References

- Archer J. Assessment of the reliability of the conflict tactics scales: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1999;14:1263–1289. [Google Scholar]

- Archer J. Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:651–680. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babcock JC, Costa DM, Green CE, Eckhardt CI. What situations induce intimate partner violence? A reliability and validity study of the Proximal Antecedents to Violent Episodes (PAVE) scale. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:433–442. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.3.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A, Walters RH. Adolescent agression. New York: Ronald Press; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew K, Horowitz LM. Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:226–244. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beere CA, King DW, Beere DB, King LA. The Sex-Role Egalitarianism Scale: A measure of attitudes toward equality between the sexes. Sex Roles. 1984;10:563–576. [Google Scholar]

- Belitsky CA, Toner BB, Ali A, Yu B. Sex-role attitudes and clinical appraisal in psychiatry residents. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;41:503–508. doi: 10.1177/070674379604100806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell KM, Naugle AE. Intimate partner violence theoretical considerations: Moving towards a contextual framework. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1096–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan KA, Clark CL, Shaver PR. Self-report measurement of adult romantic attachment: An integrative overview. In: Simpson JA, Rholes WS, editors. Attachment theory and close relationships. New York: Guilford Press; 1998. pp. 46–76. [Google Scholar]

- Brethertorn I, Munholland KA. Internal working models in attachment relationships: A construct revisited. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research and applications. New York: Guilford; 1999. pp. 89–114. [Google Scholar]

- Broussard ER. Infant attachment in a sample of adolescent mothers. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. 1995;25:211–219. doi: 10.1007/BF02250990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caesar PL. Exposure to violence in families-of-origin among wife abusers and maritally nonviolent men. Special issues: Wife assaulters. Violence and Victims. 1988;3:49–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Kim HK, Shortt JW. Observed initiation and reciprocity of physical aggression in young, at-risk couples. Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22:01–111. doi: 10.1007/s10896-007-9067-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi D, Shortt J, Crosby L. Physical and psychological aggression in at-risk couples: Stability and change in young adulthood. Merill-Palmer Quarterly. 2003;49:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cappell C, Heiner R. The intergenerational transmission of family aggression. Journal of Family Violence. 1990;5:135–152. [Google Scholar]

- Carmines EG, McIver JP. Analyzing models with unobserved variables: Analysis of covariance structures. In: Bohrnstedt GW, Borgatta EF, editors. Social Measurement: Current Issues. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1981. pp. 65–115. [Google Scholar]

- Cascardi M, Langhinrichsen J, Vivian D. Marital aggression, impact, injury, and health correlates for husbands and wives. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1992;152:1178–1184. doi: 10.1001/archinte.152.6.1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SYP, Ting K. Wife beating in South Africa: An imbalance theory of resources and power. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23:834–852. doi: 10.1177/0886260507313951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppola G, Vaughn BE, Cassibba R, Costantini A. The attachment script representation procedure in an Italian sample: Associations with adult attachment interview scales and with maternal sensitivity. Attachment and Human Development. 2006;8:209–219. doi: 10.1080/14616730600856065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosway R, Endler NS, Sadler AJ, Deary I. The Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations: Factorial structure and associations with personality traits and psychological Health. Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research. 2000;5:121–143. [Google Scholar]

- Crossman RK, Stith SM, Bender MM. Sex role egalitarianism and marital violence. Sex Roles. 1990;22:293–304. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton DG, Nicholls TL. The gender paradigm in domestic violence research and theory: Part 1- The conflict of theory and data. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2005;10:680–714. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensaft MK, Cohen P, Brown J, Smailes E, Chen H, Johnson JG. Intergenerational transmission of partner violence: A 20-years prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:741–753. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Guthreie IK, Murphy BC, Reiser M. Parental reactions to children’s negative emotions: Longitudinal relations to quality of children’s social functioning. Child Development. 1999;70:513–534. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Gershoff ET, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Cumberland AJ, Losoya SH, Murphy BC. Mothers’ emotional expressivity and children’s behavioral problems and social competence: Mediation through children’s regulation. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:475–490. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endler NS, Parker JDA. Stress and anxiety: Conceptual and assessment issues. Stress Medicine. 1990;6:243–248. [Google Scholar]

- Feeney JA, Noller P. Adult attachment. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Finkel EJ. Impelling and inhibiting forces in the perpetration of intimate partner violence. Review of General Psychology. 2007;11:193–207. [Google Scholar]

- Fox GL, Benson ML, DeMaris AA, Van Wyk J. Economic distress and intimate violence: Testing family stress and resources theories. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:793–807. [Google Scholar]

- Frankle TM. The role of attachment and a protective factor in adolescent violent behavior. Adolescent and Family Health. 2000;1:40–57. [Google Scholar]

- Glick P, Fiske ST. The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:491–512. [Google Scholar]

- Hamby SL. The Dominance Scale: Preliminary psychometric properties. Violence and Victims. 1996;11:199–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harned M. Abused women or abused men?An examination of the context and outcomes of dating violence. Violence and Victims. 2001;16:269–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzworth-Munroe A, Stuart GL, Hutchinson G. Violent versus nonviolent husbands: Differences in attachment patterns, dependency, and jealousy. Journal of Family Psychology. 1997;11:314–331. [Google Scholar]

- Hotaling GT, Sugarman DB. An analysis of risk markers in husband-to-wife violence: The current state of knowledge. Violence and Victims. 1986;1:101–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson N, Gottman J. When men batter women: New insights into ending abusive relationships. New York: Simon & Schuster; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Jasinski JL. Theoretical explanations for violence against women. In: Renzetti CM, Edleson JL, Bergan RK, editors. Sourcebook on violence against women. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. pp. 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP. Patriarchal terrorism and common couple violence: Two forms of violence against women. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:283–294. [Google Scholar]

- Kalmuss D. The intergenerational transmission of marital aggression. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1984;46:11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Ziegler E. Do abused children become abusive parents? American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1987;57:186–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1987.tb03528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiley MK. Attachment and affect regulation: A framework for family treatment of conduct disorder. Family Process. 2002;41:477–493. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2002.41312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kobak RR, Hazan C. Attachment in marriage: Effects of security and accuracy of working models. Journal Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;60:861–869. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.60.6.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong M, Bartholomew K, Henderson AJZ, Trinke S. The intergenerational transmission of relationship violence. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:288–301. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.3.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson DM. Attachment, interpersonal problems, and family of origin functioning: Differences between partner violent and non-partner violent men. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2008;9:90–105. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Hocevar D. A new, more powerful approach to multitrait-multimethod analyses: Application of second-order confirmatory factor analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1988;73:107–117. [Google Scholar]

- McCartney K, Rosenthal R. Effect size, practical importance, and social policy for children. Child Development. 2000;71:173–180. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M. Adult Attachment style and individual differences in functional versus dysfunctional experiences of anger. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:513–524. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.2.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Florian V. Exploring individual differences in reactions to mortality salience: Does attachment style regulate terror management mechanisms? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:260–273. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.2.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CM, Meyer SL, O’Leary KD. Dependency characteristics of partner assaultive men. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:729–735. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.4.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabors EL, Dietz TL, Jasinski JL. Domestic violence beliefs and perceptions among college students. Violence and Victims. 2006;21:779–794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD. Physical aggression between spouses: A social learning theory perspective. In: Van Hasselt VB, Morrison RL, Bellack AS, Hersen M, editors. Handbook of family violence. New York: Plenum; 1988. pp. 31–56. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD. Through a psychological lens: Personality traits, personality disorders, and levels of violence. In: Gelles RJ, Loseke DK, editors. Current Controversies on Family Violence. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD, Smith-Slep AM, O’Leary SG. Multivariate models of men’s and women’s partner aggression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:752–764. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prospero M. Gender differences in the relationship between intimate partner violence victimization and the perception of dating situations among college students. Violence and Victims. 2007;22:489–503. doi: 10.1891/088667007781553928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulerwitz J, Gortmaker SL, DeJong W. Measuring sexual relationship power in HIV/STD research. Sex Roles. 2000;42:637–660. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsden SR, Hubbard JA. Family expressiveness and parental emotion coaching: Their role in children’s emotion regulation and aggression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:657–667. doi: 10.1023/a:1020819915881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharfe E, Bartholomew K. Reliability and stability of adult attachment patterns. Personal Relationships. 1994;1:23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs: For generalized causal inference. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Shaver PR, Hazan C. Attachment. In: Weber A, Harvey J, editors. Perspectives on close relationships. New York: Allyn & Bacon; 1994. pp. 110–130. [Google Scholar]

- Shields A, Cicchetti D. Emotional regulation among school-age children: The development and validation of a new criterion Q-sort scale. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:906–916. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.6.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Smith MD. Patriarchal ideology and wife beating: A test of a feminist hypothesis. Violence and Victims. 1990;5:257–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PH, White JW, Holland LJ. A longitudinal perspective on dating violence among adolescent and college–age women. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:1104–1109. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.7.1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, Fleeson J. Attachment and the construction of relationships. In: Hartup W, Rubin Z, editors. Relationships and development. Hillsdale, N.J: Earlbaum; 1986. pp. 51–71. [Google Scholar]

- Steering Committee of the Physicians’ Healthy Study Research Group. Preliminary report: Findings from the aspirin component of the ongoing physicians’ health study. New England Journal of Medicine. 1988;318:262–264. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198801283180431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stets J, Straus M. Physical violence in American families. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers; 1992. The marriage license as a hitting license; pp. 227–244. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Prevalence of violence against dating partners by male and female university students worldwide. Violence against Women. 2004a;10:790–811. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Unpublished scoring manual Family Research Laboratory. University of New Hampshire; 2004b. [Google Scholar]

- Straus SM. Dominance and symmetry in partner violence by male and female university students in 32 nations. Children and Youth Services Review. 2008;30:252–275. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Gelles R, Steinmetz S. Prevalence of violence against dating partners by male and female university students worldwide. Violence against Women. 1980;10:790–811. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised conflict tactics scales (CTSZ) Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Waters HS, Rodrigues LM, Ridgeway D. Cognitive underpinnings of narrative attachment assessment. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1998;71:211–234. doi: 10.1006/jecp.1998.2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton B, Muthen B, Alwin DF, Summers GF. Assessing reliability and stability in panel models. In: Heise DR, editor. Sociological methodology. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass; 1977. pp. 84–136. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn BE, Waters HS, Coppola C, Cassidy J, Bost KK, Verissimo M. Script-like attachment representations and behavior in families and across cultures: Studies of parental secure base narratives. Attachment and Human Development. 2006;8:179–184. doi: 10.1080/14616730600856008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yllo K. Through a feminist lens: Gender, power and violence. In: Gelles RJ, Loseke DK, editors. Current Controversies on Family Violence. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Yllo K, Straus MA. Patriarchy and violence against wives: The impact of structural and normative factors. In: Straus MA, Gelles RJ, editors. Physical violence in American families: Risk factors for adaptations to violence in 8,145 families. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction; 1990. pp. 383–399. [Google Scholar]