Abstract

Background

Dysfunction of the meibomian gland (MG) is among the most frequent causes of ophthalmological symptoms. The inflammation seen in meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) is part of its pathogenesis, and evidence of the antioxidant-inflammatory properties of omega-3 fatty acids suggests this to be an appropriate treatment for MGD.

Objective

We aimed to assess the effectiveness of omega-3 fatty acids versus placebo, in improving the symptoms and signs of MGD.

Methods

We conducted a randomized and double-mask trial of 3 months duration. We enrolled 61 patients who presented with symptomatic MGD and no tear instability (defined as tear breakup time [TBUT] <10 seconds). Participants were randomly assigned to two homogeneous subgroups. For patients in group A, the study treatment included cleaning the lid margins with neutral baby shampoo and use of artificial tears without preservatives, plus a placebo oral agent. For patients in group B, the study treatment included cleaning the lid margins with neutral baby shampoo and use of artificial tears without preservatives, plus oral supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids. We performed the following tests: (1) TBUT; (2) Schirmer I test; (3) Ocular Surface Disease Index© (OSDI©; Allergan, Inc., Irvine, CA, USA); (4) MG expression; (5) evaluation of lid margin inflammation; and (6) interpalpebral and corneal dye staining.

Results

After 3 months of evaluation, the mean OSDI, TBUT, lid margin inflammation, and MG expression presented improvement from the baseline values, in group B (P < 0.01, P < 0.001, P < 0.0001, P < 0.0001, respectively). The Schirmer test results were also improved and statistically significant (P < 0.01).

Conclusion

Oral omega-3 fatty acids, 1.5 grams per day, may be beneficial in the treatment of MGD, mainly by improving tear stability.

Keywords: blepharitis, dry eye, ocular inflammation, eye discomfort, surface disease

Introduction

Dysfunction of meibomian gland (MG) is included among the most frequent causes of ophthalmological disorders and is the principal cause of dry eye.1 As stated by the report2 from an international workshop on MG dysfunction (MGD), the main mechanisms responsible for the development of obstructive MGD are increased meibum viscosity and hyperkeratinization of the ductal epithelium. These processes are influenced by aging, use of contact lenses, topical medications, and hormonal variations. We can also add acinar atrophy and inflammation as common causes of MGD. MGD should be considered as one of the most frequent causes of lipid tear deficiency, responsible for tear instability and for the appreciable shortening of the tear breakup time TBUT.3,4

The regular treatments for MGD comprise: cleansing of the lid, use of artificial tears, topical application of corticosteroids and erythromycin, and oral tetracycline/doxycycline.35 These measures are usually inefficient and do not effectively target the core mechanism of MGD. Thus, the degenerative processes (eg, hyperkeratosis) of the MG have an important influence in the MGD pathogenesis.

Tear cytokines also play an important role in chronic inflammation in MGD. When inflammatory cytokine levels in the tears of MGD patients and controls were compared, interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-7, IL-12, IL-17, and macrophage inflammatory protein-1β levels were found to be higher in the MGD patients.67 Furthermore, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α levels, and interferon-γ were higher in patients with dysfunctional tear syndrome with MGD, compared with the control group.8

Essential fatty acid supplementation has been shown to have an anti-inflammatory effect on dry eye symptoms.9 Fish oil is a source of long-chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids: eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid. The omega-3 fatty acid EPA and the omega-6 fatty acid arachidonic acid (AA) act competitively as a substrate for both the enzyme cyclooxygenase and the enzyme 5-lipoxygenase. The anti-inflammatory action is believed to result from the synthesis of prostaglandin E3 and leukotriene B5 (LTB5) from EPA that inhibits the conversion of AA to the potentially harmful inflammatory mediator’s prostaglandin E2 and leukotriene B4.10

In the present study, we evaluated the effectiveness of oral supplementation with a combined formulation of antioxidants and omega-3 in improving the signs and symptoms of diagnosed MGD, compared with placebo.

Materials and methods

This randomized, double-masked study/trial was performed with the approval of the ethics committee and the institutional review boards of the University Hospital Jiménez Díaz Foundation (Madrid, Spain). All tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki for the protection of human subjects in medical research were strictly observed.

Study design

A total of 61 subjects of both sexes, aged 23–85 years, were enrolled during ophthalmologic appointments at the study center, the University Hospital Jiménez Díaz Foundation in Madrid, Spain, between March 2012 and December 2012, according to the main inclusion/exclusion criteria listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Aged 18–85 years | Aged <23 years or >85 years |

| Diagnosed with MGD | Atopy, allergic disorders |

| Able to participate in the study | Contact lenses |

| Informed consent | Ophthalmic laser treatment (less than 3 months) Systemic diseases and general treatments Pregnancy |

| Systemic diseases and general treatments Pregnancy | |

| Systemic disease associated with dry eye | |

| Blepharitis without MGD diagnosis | |

| Ocular disorders and eye drops other than artificial tears | |

| Unable to participate in the study |

Abbreviation: MGD, meibomian gland dysfunction.

Prior to the baseline visit, subjects were required to discontinue use of nutritional supplements and related treatments, such as antibiotics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroids, and tears with vitamins, for at least 15 days. Participants were asked to strictly follow the recommendations of the ophthalmologists throughout the duration of the study. Ocular lubricants without nutritional agents were not restricted. Patients with obvious infection were excluded from the present study. Patients diagnosed with MGD were enrolled, according to criteria identified at a 2011 international workshop on MGD.11

To classify our study participants, we performed systematic ophthalmologic examinations and administered a questionnaire with objective and subjective criteria. At the baseline visit (month 0), patients were checked for signs and symptoms of MGD, and we applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the trial protocol. The assessed baseline parameters were: (1) TBUT; (2) tear quantification, (Schirmer I test);3,4 (3) Ocular Surface Disease Index© (OSDI) (American Optometric Association, St Louis, MO, USA); (4) MG expression and secretion; (5) lid margin inflammation evaluation; (6) interpalpebral and corneal dye staining; and (7) fluorescein stain of the cornea. Furthermore, patients used a daily tear complement without preservatives, which was measured. All participants were required, on a daily basis, to apply a warm compress for 5 minutes and to scrub the eye with diluted baby shampoo.

All participants additionally took an oral agent (one capsule taken with each of the three main meals per day). The participants were randomly assigned to group A or group B. Group A patients received a placebo oral supplement: 500 mg capsules incorporating sunflower oil with no other components or excipients apart from gelatin (bovine) and titanium oxide colorants, iron oxide, and hydroxides. Participants in group B received the study oral supplement formulation (Brudysec 1.5 g; Brudy Lab SL, Barcelona, Spain) reported in Table 2. The supplement for group B was based on omega-3, vitamins, glutathione, amino acids, and oligoelements in a combined nutraceutical formulation and contained (per capsule) docosahexaenoic acid (350 mg), eicosapentaenoic acid (42.5 mg), docosapentaenoic acid (30 mg), vitamin A (133.3 μg), vitamin C (26.7 mg), vitamin E (4 mg), tyrosine (10.8 mg), cysteine (5.83 mg), glutathione (2 mg), zinc (1.6 mg), copper (0.16 mg), manganese (0.33 mg), and selenium (9.17 μg).

Table 2.

Composition of Brudysec 1.5 g (Brudy Lab SL, Barcelona, Spain), per capsule

| Nutrient | Amount |

|---|---|

| DHA | 350 mg |

| EPA | 42.5 mg |

| Vitamin A | 133.3 μg |

| Vitamin C | 26.7 mg |

| Vitamin E | 4 mg |

| Tyrosine | 10.8 mg |

| Cysteine | 5.83 mg |

| Glutathione | 2 mg |

| Zinc | 1.6 mg |

| Copper | 0.16 mg |

| Manganese | 0.33 mg |

| Selenium | 9.17 μg |

| DPA | 30 mg |

Abbreviations: DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; DPA, docosapentaenoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid.

The objective factors were reassessed at follow-up visits 1, 2, and 3 months after the assigned treatments began. The objective factors were evaluated by one investigator (AO) to reduce interobserver variability. We assumed a self-administered medical therapy has only 50% adherence, so at each visit, the patients were required to deliver the empty boxes of medication received, in order to improve compliance as well as to ensure the validity of the final data of the study. Subjects were followed up monthly, for 3 months after the initial visit.

Patient management

Personal interviews were conducted with all participants to obtain their personal and familial backgrounds and characteristics of their disease, mainly symptoms of MGD. The OSDI questionnaire assessed the frequency of dry eye symptoms and problems with the ocular surface.12 The OSDI assessed the participants’ condition as normal, mild, moderate, or severe.

All participants underwent a systematic ophthalmologic examination to determine best corrected visual acuity in each eye. The objective signs were evaluated by means of a slit-lamp IS-600II Topcon (Topcon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) examination (lid margin inflammation and MG expression), staining of the conjunctiva and cornea with fluorescein (Oxford Test),13 measurement of TBUT,3,4 and the quantification of the tear assessed by Schirmer I test. Lid margin inflammation severity was scored: 0, no injection; 1, injection (presence of conjunctival vessels congestion and/or hyperemia) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Baseline patient characteristics

| Characteristic | Placebo (group A; n = 31) | Omega-3 (group B; n = 33) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male, n (%) | 9 (29.03) | 9 (27.2) |

| Female, n (%) | 22 (70.97) | 24 (72.8) |

| Age in years, mean | 54 | 58 |

| Signs | ||

| Lid margin inflammation severity, n (%) | ||

| No injection | 9 (29.03) | 10 (30.3) |

| Injection | 22 (70.97) | 23 (69.7) |

| Meibomian gland secretion, n (%) | ||

| Clear fluid | 1 (3.22) | 4 (12.12) |

| Cloudy fluid | 21 (67.74) | 20 (60.60) |

| Cloudy particulate fluid | 6 (19.35) | 8 (24.24) |

| Inspissated, like toothpaste | 3 (9.68) | 1 (3.03) |

| No secretion | 0 | 0 |

| Mean TBUT (SD), s | 6.45 (2.57) | 6.94 (2.75) |

| Mean Schirmer I (SD), mm | 16.61 (7.57) | 18.94 (7.47) |

| Cornea staining data. Oxford test, n (%) | ||

| Grade 0 | 23 (74.2) | 22 (66.7) |

| Grade I | 5 (16.1) | 11 (33.3) |

| Grade II to IV | 3 (9.7) | 0 (0) |

| Symptoms | ||

| OSDI© | ||

| Normal | 2 | 0 |

| Mild | 7 | 4 |

| Moderate | 12 | 17 |

| Severe | 10 | 12 |

Abbreviations: OSDI©, Ocular Surface Disease Index; SD, standard deviation; TBUT, tear breakup time; s, seconds.

MGD was defined as abnormal discharge and/or anomalous expression when a finger was placed on both palpebral lids: clear fluid, cloudy fluid, cloudy particulate fluid, or inspissated and toothpaste-like (Table 3).1 The primary ophthalmologic outcome measures for effectiveness of the oral nutraceutical formulation were fluorescein staining and TBUT; the secondary measures were Schirmer I test and dry eye symptoms.12

TBUT was measured by instillation of one drop of 2% fluorescein. The time until disappearance of the dye was recorded, and the average of three trials was calculated. On the other hand, we used the Oxford Test in order to evaluate the corneal fluorescein. Also, the Schirmer I test (quantification of the tear) was applied during a 5 minute interval, without anesthesia. We evaluated the safety outcomes by means of ophthalmological explorations, and any adverse events that occurred, during the whole of the research.

Statistical analysis

We analyzed the outcomes of patients’ right eyes. The most significant results came from the TBUT test. Statistics are reported as mean values and standard deviations. We used dependent-samples Student’s t (TBUT and Schirmer), McNemar (inflammation of the lids and expression of the MG), and Wilcoxon tests (OSDI and Oxford) for intragroup and intergroup comparisons. Both intragroup and intergroup comparisons were made with an intention-to-treat analysis. P-values (two-sided) less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, Version 11.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Patient demographics

We recruited 64 patients in the research; 31 were assigned to group A, and 33 were assigned to group B. Three patients (from group B) were withdrawn from the study: two (3.12%) because of drug intolerance, and one (1.56%) did not pursue the treatment.

Sixty-one patients completed the study: 31 (50.82%) in group A and 30 (49.18%) in group B. The mean age of the group B patients was 58 years and was 54 years for group A. Most of the patients involved in the study were women, but we did not observe significant differences in the sex distribution for both groups.

Additionally, we did not observe significant intergroup differences in baseline signs and symptoms. Table 3 summarizes the baseline data, including demography, and the signs and symptoms. Throughout the randomized study, the investigators and patients were blinded to the treatment assignments.

Treatment responses

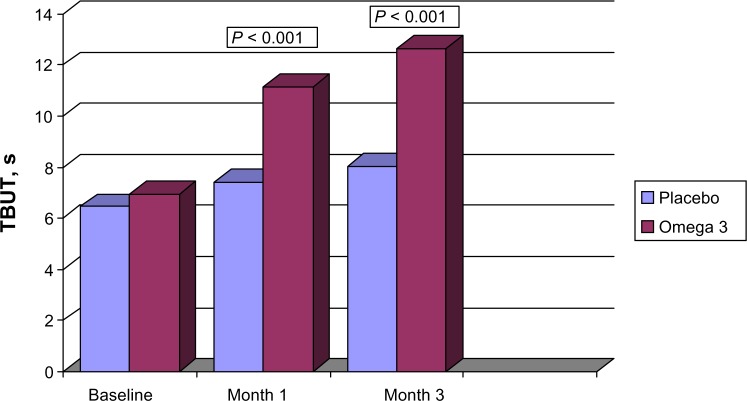

At baseline, the mean TBUT was 6.45 (2.57) seconds and 6.94 (2.75) seconds for groups A and B, respectively (Table 3). At each monitoring, the mean TBUT for group B was greater than the baseline and the group A values. The TBUT at the final follow-up visit was 8.03 (2.86) seconds and 12.63 (1.75) seconds in group A and in group B, respectively (P < 0.01) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Changes in mean tear breakup time, from baseline to month 3, in subjects assigned to omega-3 or placebo.

Note: The differences between month 3 and baseline values were statistically significant (P < 0.001).

Abbreviation: TBUT, tear breakup time; s, seconds.

In the control group (group A), the TBUT did not change significantly from baseline. However in group B, lid inflammation was decreased significantly compared with baseline, at each follow-up (P < 0.0001).

In group B, the MG expressibility was significantly greater than baseline, at 1 month (P = 0.01) and at 3 months (P < 0.0001); group A did not present a change in expressibility.

In both groups, cornea staining data presented no significant differences from baseline, although the group B results were lower at each monitored visit.

The mean tear quantification was assessed by the Schirmer I test, without anesthesia. At baseline, this was 16.61 (7.57) mm in group A and 18.94 (7.47) mm in group B. The tear quantification results at 3 months were not significantly different from baseline in either group.

The dysfunctions of the tear were evaluated using the OSDI test. Both groups exhibited a decrease in tear dysfunction symptoms in group B, the decrease was observed at 1 month and 3 months (P = 0.01 and P = 0.09, respectively), and in group A, this was also observed at both of the follow-up visits (P = 0.09 and P = 0.003, respectively).

Discussion

The main cause of MGD is hyperkeratinization and its related pathogenesis (for example, ductal dilatation and acinar atrophy). Other pathologies, such as atopy, pemphigoid acne rosacea, and seborrhea are related to MGD and may result in a chronic inflammation of the ocular surface.14 Thus, all these circumstances may also lead to dry eye, the alteration of the tear, and irritation of the eye shown by MGD patients.

Furthermore, other factors, such as: IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, TNF-α levels, and interferon-γmay be increased in MGD;8,15 the latter may explain the irritation and lid inflammation symptoms noticed in patients with this disorder. Based on these effects, inflammatory properties may be targeted in the treatment of MGD.

The anti-inflammatory power of essential polyunsaturated fatty acids used in treatment of the ocular surface may be compared with corticosteroids, as they act as the same mediator, through nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) signal transduction, of the inflammation cascade.16 The inflammation at the lid margin presented improvement from the baseline in group B (who took the omega-3 fatty acids supplement), and consequently, this study suggests that omega-3 fatty acids may improve tear film stability, decrease the inflammation of lid margins, and recover the homeostasis of ocular surface in patients with MGD.

Wojtowicz et al17 did not find statistically significant differences between omega-3 and placebo in the treatment of dry eye; nevertheless, we did find statistically significant differences in our assessment of the TBUT test after treatment with omega-3 for MGD. This study is a starting point for further research into the benefit of omega-3 fatty acids for inflammatory disease of the ocular surface, and other studies should aim to quantify the beneficial effect of omega-3 fatty acids in MGD with evaporative dry eye, for example, by incrementally increasing the dose of omega-3 fatty acids and assessing the anti-inflammatory effect. We should also consider other research improvements, for eg, balancing the ratio of males to females in the study population.

A strength of this research is that it was randomized and double-masked, which may have minimized any partiality. The main outcome measure of efficacy was tear film stability, and greater differences might have been observed in a larger patient sample. A larger, controlled, and multicenter study may be required in order to confirm whether this improvement in tear stability is applicable to clinical practice.

Adverse events

No serious adverse events arose during the research. Of 64 patients, two patients (3.12%) in the preliminary-stage (intention-to-treat) analysis group reported digestive upset with omega-3 treatment. These symptoms arose within the first month of treatment, and the patients recovered immediately after stopping the medication.

Conclusion

To conclude, this research established that omega-3 fatty acids, 1.5 g, can increase TBUT in subjects with MGD. Thus, when conventional treatment (artificial tears) has proven unsatisfactory for patients with MGD, omega-3 fatty acids, 1.5 g, may be an effective adjunctive treatment.

Acknowledgments

The food supplements used this trial were provided by Brudy Lab SL, Barcelona, Spain.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Foulks GN, Bron AJ. Meibomian gland dysfunction: a clinical scheme for description, diagnosis, classification, and grading. Ocul Surf. 2003;1(3):107–126. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knop E, Knop N, Millar T, Obata H, Sullivan DA. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: report of the subcommittee on anatomy, physiology, and pathophysiology of the meibomian gland. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(4):1938–1978. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6997c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathers WD. Meibomian gland disease. In: Pflugfelder SC, Beuerman RW, Stern ME, editors. Dry Eye and Ocular Surface Disorders. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker Inc; 2004. pp. 247–267. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Driver PJ, Lemp MA. Meibomian gland dysfunction. Surv Ophthalmol. 1996;40(5):343–367. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(96)80064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bron AJ, Benjamin L, Snibson GR. Meibomian gland disease. Classification and grading of lid changes. Eye (Lond) 1991;5(Pt 4):395–411. doi: 10.1038/eye.1991.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim JT, Lee SH, Chun YS, Kim JC. Tear cytokines and chemokines in patients with Demodex blepharitis. Cytokine. 2011;53(1):94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Solomon A, Dursun D, Liu Z, Xie Y, Macri A, Pflugfelder SC. Pro- and anti-inflammatory forms of interleukin-1 in the tear fluid and conjunctiva of patients with dry-eye disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42(10):2283–2292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lam H, Bleiden L, de Paiva CS, Farley W, Stern ME, Pflugfelder SC. Tear cytokine profiles in dysfunctional tear syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147(2):198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.08.032. e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brignole-Baudouin F, Baudouin C, Aragona P, et al. A multicentre, double-masked, randomized, controlled trial assessing the effect of oral supplementation of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids on a conjunctival inflammatory marker in dry eye patients. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011;89(7):e591–e597. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2011.02196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.James MJ, Gibson RA, Cleland LG. Dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammatory mediator production. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71(Suppl 1):343S–348S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.1.343s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomlinson A, Bron AJ, Korb DR, et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: report of the diagnosis subcommittee. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(4):2006–2049. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6997f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schiffman RM, Christianson MD, Jacobsen G, Hirsch JD, Reis BL. Reliability and validity of the Ocular Surface Disease Index. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118(5):615–621. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.5.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Methodologies to diagnose and monitor dry eye disease: report of the Diagnostic Methodology Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye Workshop Ocular Surface 2007April52108–152.Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17508118Accessed July 1, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nichols KK, Foulks GN, Bron AJ, et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: executive summary. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(4):1922–1929. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6997a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Enríquez-de-Salamanca A, Castellanos E, Stern ME, et al. Tear cytokine and chemokine analysis and clinical correlations in evaporative-type dry eye disease. Mol Vis. 2010;16:862–873. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erdinest N, Shmueli O, Grossman Y, Ovadia H, Solomon A. Anti-inflammatory effects of alpha linolenic acid on human corneal epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(8):4396–4406. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-9724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wojtowicz JC, Butovich I, Uchiyama E, Aronowicz J, Agee S, McCulley JP. Pilot, prospective, randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled clinical trial of an omega-3 supplement for dry eye. Cornea. 2011;30(3):308–314. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181f22e03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]