Patient reports of their communication experiences during cancer care could increase understanding of the communication process, stimulate improvements, inform interventions, and provide a basis for evaluating changes in communication practices.

Abstract

Purpose:

Patient-centered communication is critical to quality cancer care. Effective communication can help patients and family members cope with cancer, make informed decisions, and effectively manage their care; suboptimal communication can contribute to care breakdowns and undermine clinician-patient relationships. The study purpose was to explore stakeholders' views on the feasibility and acceptability of collecting self-reported patient and family perceptions of communication experiences while receiving cancer care. The results were intended to inform the design, development, and implementation of a structured and generalizable patient-level reporting system.

Methods:

This was a formative, qualitative study that used semistructured interviews with cancer patients, family members, clinicians, and leaders of health care organizations. The constant comparative method was used to identify major themes in the interview transcripts.

Results:

A total of 106 stakeholders were interviewed. Thematic saturation was achieved. All stakeholders recognized the importance of communication and endorsed efforts to improve communication during cancer care. Patients, clinicians, and leaders expressed concerns about the potential consequences of reports of suboptimal communication experiences, such as damage to the clinician-patient relationship, and the need for effective improvement strategies. Patients and family members would report good communication experiences in order to encourage such practices. Practical and logistic issues were identified.

Conclusion:

Patient reports of their communication experiences during cancer care could increase understanding of the communication process, stimulate improvements, inform interventions, and provide a basis for evaluating changes in communication practices. This qualitative study provides a foundation for the design and pilot testing of such a patient reporting system.

Introduction

The focus on patient-centered medical homes and the creation of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute as part of the Affordable Care Act has increased appreciation of the importance of patient-centered care.1–2 Patient-centered communication is defined as “healthcare that establishes a partnership among practitioners, patients, and their families (when appropriate) to ensure that decisions respect patients' wants, needs, and preferences and that patients have the education and support they need to make decisions and participate in their own care.”3(p41) Optimizing communication between patients, family members, and clinical teams is critical for achieving this goal.4 Patient-centered communication is especially important in the context of a potentially life-threatening illness such as cancer.5 Effective communication during cancer care contributes to better patient outcomes,6 whereas communication breakdowns may contribute to patient distress and interfere with care.7–11

To improve the delivery of patient-centered care, health care organizations have been encouraged to monitor and strengthen the quality of patient-clinician relationships and interactions.12 Efforts to operationalize patient-centered communication have begun.13 A system that captures patients' reports of their communication experiences over the course of cancer care could help to identify communication best practices. It could also help in identifying causes of suboptimal communication and prioritizing targets for intervention, as well as in evaluating the effectiveness of interventions intended to improve communication.5,14–16

The purpose of this qualitative study was to explore stakeholders' views on the design of such a system, as well as acceptability, feasibility, logistics, and barriers. Our intent was to inform the development and implementation of a system that would encourage meaningful and accurate reporting from patients; generate valid and actionable feedback for clinicians and health care system leaders; and ultimately facilitate the delivery of high-quality, patient-centered care.

Methods

Study Design

Because of the formative nature of the research questions, we used qualitative methods and conducted semistructured interviews with cancer patients, family members, cancer care clinicians, and health care organization leaders. Purposive sampling was used to identify stakeholders with diverse perspectives.

Study Setting

The study was conducted within the Cancer Research Network's Cancer Communication Research Center. The Cancer Research Network involves a consortium of 14 research organizations affiliated with integrated health care delivery systems with the goal of improving cancer care through population-based research.17 The Cancer Communication Research Center seeks to identify and describe optimal communication structures and processes to facilitate patient-centered cancer communication. The institutional review boards of the participating sites approved the study.

Study Sample

Patients and family members were recruited from sites in Massachusetts and Colorado. Invitations were sent to adult patients who had received a cancer diagnosis in the previous 6 months; patients with nonmelanoma skin cancer and prostate cancer in active surveillance were excluded. Two weeks later, patients who had not responded were called. Patients referred interested family members. Nurses at an ambulatory pediatric cancer clinic in Massachusetts identified parents of patients as potential participants; these parents were invited in person by a research assistant. Pediatric patients were not recruited.

Clinicians and health care organization leaders were recruited from six sites that represented integrated health systems and multispecialty group practices in Colorado, Massachusetts,2 Oregon, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. Invitees included chief medical officers, chief medical informatics officers, chiefs of primary care and oncology, information technology leaders, primary care physicians, oncologists, oncology nurses and nurse practitioners, and surgeons.

Data Collection

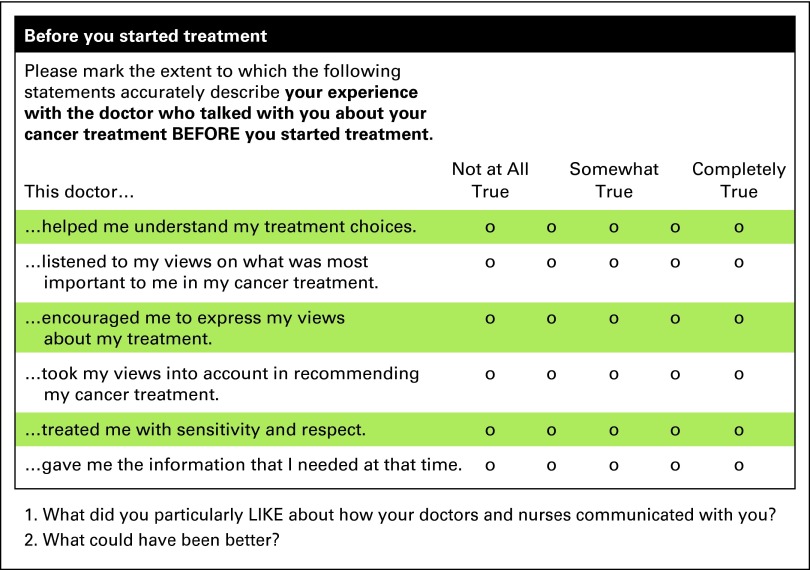

Interviewees provided informed consent. Interviews were conducted in person or by telephone, according to interviewee's preference. Interviews were semistructured; the interviewer followed an interview guide but diverged to explore topics in depth or to clarify. The interviewer presented sample items for interviewees to react to (Appendix A1, online only). Patient and family member interviews explored a range of topics, including barriers and facilitators to reporting, as well as willingness to report both positive and negative experiences. Practical issues, such as the optimal number of questions, were also explored. Parents of pediatric patients were asked their views on surveying pediatric patients directly.

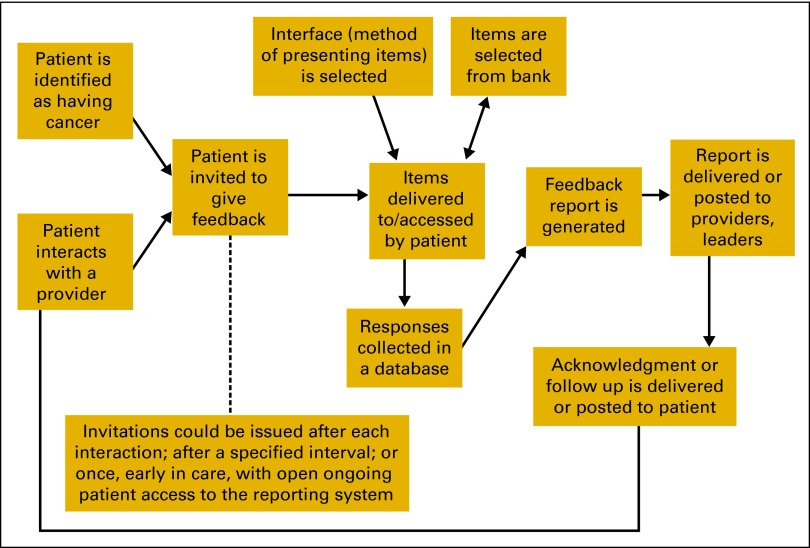

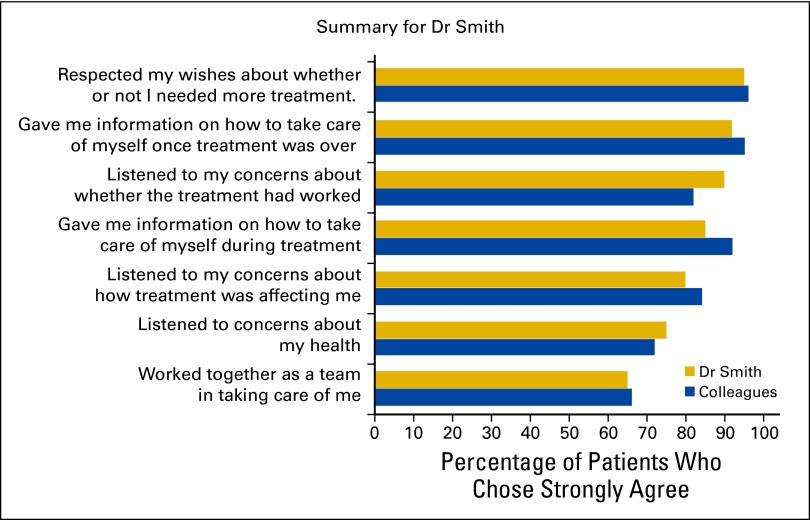

Clinicians and leaders were asked about their reactions to surveying patients regarding their communication experiences and the anticipated value of feedback reports. They were shown diagrams that summarized how a feedback system might work (Appendix Figure A2, online only), a sample feedback report (Appendix Figure A3, online only), and sample items.

Limited demographic information was collected. Patient and family member interviews lasted approximately 60 minutes; clinician and leader interviews lasted approximately 30 minutes. Interviews were recorded and transcribed. Interviewees received a $50 gift card or cash.

Data Analysis

Transcript content analysis occurred iteratively, with the study goals and the interview questions providing an initial organizing framework. Codes for capturing themes expressed by patients and family members were established and applied separately from codes for the clinician and leader responses. Authors with experience in qualitative data analysis (K.M., B.G., C.L., C.F., J.B.) began by reviewing transcripts and developing preliminary codes. Analysis proceeded with discussion and repeated revision of the code list until the team concurred that the codes provided a thorough and accurate description of the range of views expressed during the interviews.. After initial coding, transcripts were re-reviewed to identify additional subthemes and to check coding consistency. Constant comparison continued until the core and related categories were determined to be sufficiently saturated and further coding and comparison yielded no new concepts.

Results

Participants

Thirty-seven patients and 17 family members participated. A variety of cancer diagnoses were represented (Table 1).

Table 1.

Adult Patient and Family Member Characteristics

| Characteristic | Adult Patients (n = 37) |

Family Members of Patients (n = 17) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No | % | |

| Age, years | ||||

| Mean | 61.92 | 58.6 | ||

| SD | 8.9 | 6.35 | ||

| Range | 37-81 | 50-66 | ||

| 31-40 | 1 | 3 | 0 | |

| 41-50 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 6 |

| 51-60 | 10 | 27 | 2 | 12 |

| 61-70 | 20 | 54 | 2 | 12 |

| 71-81 | 4 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 12 | 71 |

| Cancer type | ||||

| Breast | 16 | 43 | 3 | 18 |

| Thyroid | 6 | 16 | 1 | 6 |

| Leukemia | 0 | 0 | 5 | 29 |

| Prostate | 3 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Skin | 3 | 8 | 2 | 12 |

| Bladder | 2 | 5 | 1 | 6 |

| Uterine | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Renal | 2 | 5 | 1 | 6 |

| Other | 3 | 8 | 3 | 18 |

| Missing | 0 | 1 | 6 | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| African American | 1 | 3 | 1 | 6 |

| Asian | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hispanic | 1 | 3 | 2 | 12 |

| White | 35 | 94 | 14 | 82 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Fifty-two clinicians and leaders from six organizations participated, including chief medical officers (n = 2), clinical and medical information systems experts and leaders (n = 11), department chiefs or chairs (n = 16), education and development staff (n = 2), directors of quality (n = 4), and clinicians without specific leadership roles (n = 17). Two organizations were multispecialty group practices and four were integrated health systems.

Findings are presented according to the core themes relating to substantive issues that emerged from the qualitative analysis: general reactions to a system for collecting patient reports of communication experiences, question focus, concerns about reporting communication experiences, and practical and logistical issues. Patient and family member responses are presented first for each category, followed by clinician and leader responses. Themes related to practical and logistical issues are summarized last, in tabular form.

General Reactions to Patient Reporting of Communication Experiences During Cancer Care

Interviewees reacted positively to the idea of patients and families providing feedback on their communication experiences. Communication was viewed as an essential component of care, and efforts to improve communication were seen as valuable. One clinician said, “I think it's a valuable thing, and I think it needs to be done. Because an important part of care delivery is how well have you communicated to the patient their own health situation.”

Patients and family members were motivated by their desire to improve communication. One parent stated that parents would be willing to report “if they know that it's going to help another child or if another parent get through it. So as long as they know that, I don't think any parent wouldn't fill it out” Patients and family members would report problematic communication in the hope that problems would be addressed; they would report good experiences to encourage such practices. One patient remarked “the two hour conversation I had with my primary care that was so unbelievably beneficial, I wanted to tell the world … I want to be able to tell somebody what a difference those things make.”

Clinicians and leaders also valued good communication, and some anticipated that patient reporting would contribute to better communication. As one clinician reported “I think sometimes we think we do a great job [communicating], but if a patient doesn't get the information, we've done them a disservice. So if there's something we can do to better…I don't see how that would be a bad idea.” A patient reporting system could identify clinicians with exceptional communication skills, who might in turn serve as models, mentors or coaches, as well as provide feedback for clinicians seeking to improve.

Question Focus

Patients and family members felt the sample questions covered important content, were relevant, and differed significantly from questions on satisfaction surveys they had received. They suggested that type of cancer, treatment, and prognosis should be considered in creating and selecting questions, though they acknowledged that doing so would complicate reporting and feedback. Patients and family members felt that most questions about communication experiences should focus on individual clinicians because, as one respondent stated, “for the most part, they were very good. So if you're going to lump them together, if you have one or two persons that you don't have a good experience with, it's not fair to the others.” However, some agreed that the inclusion of questions about team communication might be appropriate.

Clinicians and leaders recognized the importance of assessing communication at the clinician level, but they were also interested in system and team communication. They identified transitions between providers and coordination of care as especially important aspects of the patient experience. As one information system leader noted, “We are always thinking of things from a systems perspective and how to make the system more efficient. But we really do need to put ourselves in the patient's shoes to try to maximize meeting their needs and then trying to find a balance between the two: the patient's needs and making the system efficient.”

Concerns

While interviewees acknowledged the potential benefits of a communication reporting system, many expressed concerns or qualified their support. Some patients would be willing to report frankly regardless of whether they would be identifiable, but many more indicated that they would want anonymity, as exemplified by this comment: “Well I think it's really important that it truly, truly not get back to the doctors …. Because we work with these doctors for a long time. It truly needs to be anonymous.” Patients and family members also voiced concerns that reporting suboptimal experiences might hurt the clinician's feelings or result in negative consequences. For some, this worry stemmed from concerns about damaging the clinician-patient relationship, whereas others were concerned about consequences to the clinician: “I wouldn't want anyone to catch any heck out of it, you know?”

Leaders and clinicians recognized the importance of patient anonymity, with a few expressing the belief that some providers would not wish to continue caring for dissatisfied patients. As one clinical leader said, “My concern is if it's an ongoing relationship, I can't predict how the doctor will feel if they get a patient who either legitimately or nonlegitimately…is reacting negatively to an interaction. And I wouldn't want anything to disrupt the care.” Some were concerned that financial consequences, such as provider bonuses, might be attached to patient reports of communication and specifically recommended against this. Some also recommended against sharing reports outside of the health care organization.

Most patients would not want a response after reporting of good experiences; however, most would want a response if they reported a problem. Leaders were concerned that acknowledging feedback from patients could create false expectations for change. “they may have their hopes up that a specific concern was addressed, and I don't want to set us up to fail by not addressing it.” Leaders and clinicians also voiced concerns about their ability to respond to feedback about suboptimal performance, and would want resources to improve communication; “So if, for example, we went to Dr. X and said, ‘We've surveyed 40 of your patients, and one of the summary findings is that patients feel they don't have enough information on how to take care of themselves,' well the next step for that doctor is not clear, because he's probably given them lots of information …. So I think what would be more helpful to that doc is to make clear what interventions do seem to work.” Others had resources available, such as existing programs for communication skills training or coaching.

Some leaders and clinicians predicted that some clinicians would not be receptive to feedback and might discount or dismiss negative feedback in particular. As one interviewee said, “…there will be a segment [of clinicians] that will object. And I mean that's the reality. And I think for that reason, it needs… to be done in a very kind of nonthreatening/intimidating way. This is done for educational purposes only. It's not a grade. It's not going to be sent to your insurance company for them to decide how much to pay you.” But concerns about clinicians' responses were not universal; some leaders and clinicians believed that most physicians would be open to feedback.

Practical and Logistical Issues

Practical issues for patients and family members included questionnaire length, question type and focus, interval between subsequent questionnaires, and modality (Table 2). Practical issues for clinicians and leaders included details of feedback and reporting, ability to respond to feedback, and congruence with larger organizational goals (Table 3).

Table 2.

Patients' and Family Members' Views on Practical Issues

| Themes Identified in Patients' and Family Members' Responses |

|---|

Could a family member serve as a respondent for the patient?

|

At what point would patients and family members be willing to report on their experiences?

|

Would patients and family members complete questionnaires about their communication experiences repeatedly?

|

How many items would be acceptable?

|

How long would patients or family members be willing to spend to complete a questionnaire?

|

Preference for questionnaire construction

|

What delivery mode would be preferred?

|

Should questions focus on communication with individual clinicians, or with care teams?

|

Should the system be available at all times for patients to access at will, or should patient reports be actively solicited periodically ?

|

Table 3.

Clinicians', Health Plan Leaders', and Information Technology Specialists' Views on Practical Issues Related to Communication

| Themes Identified in Clinicians' and Health Care Organization Leaders' Responses |

|---|

What is your reaction to the possibility of a patient survey focused on communication specifically?

|

Would providers and leaders find this type of feedback useful?

|

What level of aggregation would you want to see?

|

Would you act on the basis of results such as these?

|

Would you, or others in your organization, be able to respond in a timely manner if a patient reported a problem?

|

How would such a system fit with organizational goals?

|

Discussion

The growing recognition of the importance of patient-centered communication in cancer care and the potentially devastating consequences of communication breakdowns underscore the need to optimize clinician-patient communication throughout cancer care. A system for collecting and monitoring patient reports of their communication experiences over the course of care, with feedback to clinicians and organizations, could be an important first step toward that goal.12,16 Unlike current patient experience surveys that include few communication items and are administered to only a cross-sectional patient sample, we believe there is a need for a system that facilitates the longitudinal, detailed assessment of the quality of patient-centered communication, administered to every patient receiving care. Our findings suggest that such a system would have value for patients, family members, clinicians, and health care leaders.

Patients and family members in this study were unanimous in valuing good communication and were willing to share their experiences in order to improve communication; clinicians and leaders concurred that communication is important. Patients' and family members' responses suggest that an optimal patient reporting system will need to be adaptive, with questions tailored to their particular cancer, treatment trajectory, stage of care, care team, and individual clinicians. Clinicians and leaders want reports that are actionable, with benchmarks and comparative data that facilitate comparisons across clinicians and organizations. An important preliminary step will be to determine the optimal level of adaptive administration that is sensitive to patients' needs and preferences and useful for clinicians and leaders.

To encourage honest reporting of suboptimal communication experiences, the system will need to allow anonymous reporting. Clinicians' and leaders' predicted mixed reactions to patient reports of suboptimal communication, as they expressed concerns about both the reactions of individual clinicians and the availability of effective interventions. If patient reporting systems are implemented in test settings, shown to contribute to real improvements in care, and contribute actionable information not captured on existing patient surveys, leaders are likely to become more receptive. Future efforts at developing and implementing such systems will have to demonstrate a positive cost-benefit ratio to facilitate adoption by health care leaders.

One challenge in collecting patient reports of communication during cancer care is that during the diagnosis and treatment process, patients and family members are focused on fighting the disease and may be reluctant to expend energy on reporting. Further, though patients may be willing to report on their experiences over time, they would prefer to do so relatively infrequently. Thus, it may not be feasible to capture experiences during or immediately after key events such as diagnosis or treatment decision making. This could affect report accuracy and possibly preclude timely and effective responses on the part of the clinician or organization. Current patient experience assessments using the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems surveys have, however, demonstrated the validity of patient responses over a recall period of as long as 12 months.18 Further, patients who are at advanced disease stage at diagnosis, and thus possibly near death, would likely not report on their experiences, potentially resulting in biased reports. In such situations, it may be especially important to engage family members to provide proxy reports on behalf of patients, a practice adopted in many patient experience studies. At a minimum, it will be necessary to recognize the potential for bias.

The strengths of this study include the diverse sample of key stakeholders from multiple sites and two types of health care organizations, as well as the use of semistructured interviews that encouraged interviewees to speak freely and allowed in-depth exploration of the complexities of the issues. Limitations include the relatively modest number of interviewees, and the fact that patients and family members were interviewed well after diagnosis. The patients in this study were either receiving treatment as outpatients or had completed treatment, and the interviewer did not explore whether their views might differ as a function of setting (ie, outpatient v inpatient). In addition, almost all of the patients and family members were white, so we were unable to assess whether these findings hold true for members of other racial/ethnic groups. These factors may have limited the generalizability of our findings and should be explored in future work.

In 2007, the Kalamazoo II statement highlighted the need to improve communication assessment and to incorporate the patients' perspective.19 Patient surveys—such as that considered here—are a widely used and relatively efficient assessment method, but direct observation and examination techniques can provide important information as well.19 Direct observation and assessment of clinicians' behaviors during encounters with actual or standardized patients are widely used in medical education and in licensure examinations.20–22 Oral, essay, and multiple-choice response examinations are less widely used, but recent developments integrating videos and new response methods have shown promise.23–24

This study provides a foundation for the design and pilot testing of a patient reporting system focused on communication during cancer care, and it also has implications for the design and implementation of communication assessment systems focused on other chronic illness settings. Such a system could increase understanding of the communication process, stimulate improvements, inform interventions, and provide a basis for evaluating changes in communication practices.

Though this study represents a first step toward developing such a system, several key questions remain unanswered. The actual design of a system—including the items used, the adaptability of the data collection system, how feedback is delivered and acted on at multiple levels of the organization, and the costs—require further study. Moreover, the appropriate time and way to introduce the system to patients will need to be identified. Further exploration might include the use of patient navigators or other trusted members of the health care team to facilitate this process. Ultimately, it will be necessary to implement such a system to confirm or refute stakeholders' expectations and concerns.

Acknowledgment

This study was conducted in the Cancer Communication Research Center (P20CA137219). Original data collection was funded by this grant, by a Cancer Research Network pilot grant (U19CA79689) from the National Cancer Institute, and a Clinical and Translational Science Award pilot grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, through Grant No. 8UL1TR000161.

Presented as a poster presentation at the International Conference on Communication in Health Care/American Academy on Communication in Health Care Annual Conference, Chicago, IL, April 29-May 2, 2012, and at the HMO Research Network Annual Conference, Seattle, WA, October 16-19, 2012.

Appendix

Figure A1.

Sample items assessing six core functions of patient-centered communication reviewed by stakeholders. The six core functions of patient-centered communication are (1) fostering clinician-patient relationships, (2) exchanging information, (3) responding to patients' emotions, (4) managing uncertainty, (5) making decisions, and (6) enabling patient self-management.6

Figure A2.

Feedback flow chart.

Figure A3.

Sample feedback report. Diagram given to participants for reaction and feedback.

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Kathleen M. Mazor, Bridget Gaglio, Larissa Nekhlyudov, Mark C. Hornbrook, Kathleen Walsh, Neeraj K. Arora

Financial support: Kathleen M. Mazor, Neeraj K. Arora

Administrative support: Kathleen M. Mazor, Bridget Gaglio, Mark C. Hornbrook, Celeste A. Lemay, Cassandra Firneno, Colleen Biggins

Provision of study materials or patients: Kathleen M. Mazor, Bridget Gaglio, Larissa Nekhlyudov, Gwen L. Alexander, Azadeh Stark, Mark C. Hornbrook, Kathleen Walsh, Jennifer Boggs, Mary Ann Blosky

Collection and assembly of data: Kathleen M. Mazor, Bridget Gaglio, Gwen L. Alexander, Azadeh Stark, Mark C. Hornbrook, Kathleen Walsh, Jennifer Boggs, Celeste A. Lemay, Cassandra Firneno, Colleen Biggins, Mary Ann Blosky

Data analysis and interpretation: Kathleen M. Mazor, Bridget Gaglio, Larissa Nekhlyudov, Mark C. Hornbrook, Kathleen Walsh, Jennifer Boggs, Celeste A. Lemay, Cassandra Firneno, Colleen Biggins

Manuscript writing: Kathleen M. Mazor, Bridget Gaglio, Larissa Nekhlyudov, Gwen L. Alexander, Mark C. Hornbrook, Kathleen Walsh, Jennifer Boggs, Celeste A. Lemay, Cassandra Firneno, Neeraj K. Arora

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

References

- 1.Selby JV, Beal AC, Frank L. The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) national priorities for research and initial research agenda. JAMA. 2012;307:1583–1584. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stange KC, Nutting PA, Miller WL, et al. Defining and measuring the patient-centered medical home. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:601–612. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1291-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hurtado MP, Swift EK, Corrigan JM. Envisioning the National Health Care Quality Report. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levinson W, Lesser CS, Epstein RM. Developing physician communication skills for patient-centered care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:1310–1318. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arora NK, Street RL, Jr, Epstein RM, et al. Facilitating patient-centered cancer communication: A road map. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77:319–321. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Epstein R, Street R., Jr . Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ayanian JZ, Zaslavsky AM, Guadagnoli E, et al. Patients' perceptions of quality of care for colorectal cancer by race, ethnicity, and language. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6576–6586. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wagner EH, Aiello Bowles EJ, Greene SM, et al. The quality of cancer patient experience: Perspectives of patients, family members, providers and experts. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19:484–489. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2010.042374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butler L, Degner L, Baile W, et al. Developing communication competency in the context of cancer: A critical interpretive analysis of provider training programs. Psycho-oncology. 2005;14:861–872. doi: 10.1002/pon.948. discussion 73-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thorne S, Armstrong EA, Harris SR, et al. Patient real-time and 12-month retrospective perceptions of difficult communications in the cancer diagnostic period. Qual Health Res. 2009;19:1383–1394. doi: 10.1177/1049732309348382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazor KM, Roblin DW, Greene SM, et al. Toward patient-centered cancer care: Patient perceptions of problematic events, impact, and response. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1784–1790. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levinson W, Pizzo PA. Patient-physician communication: It's about time. JAMA. 2011;305:1802–1803. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCormack LA, Treiman K, Rupert D, et al. Measuring patient-centered communication in cancer care: A literature review and the development of a systematic approach. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:1085–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schofield PE, Butow PN. Towards better communication in cancer care: A framework for developing evidence-based interventions. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;55:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Street RL, Jr, Makoul G, Arora NK, et al. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74:295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arora NK. Advancing research on patient-centered cancer communication. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;70:301–302. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagner EH, Greene SM, Hart G, et al. Building a research consortium of large health systems: The Cancer Research Network. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2005;35:3–11. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgi032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris-Kojetin LD, Fowler FJ, Jr, Brown JA, et al. The use of cognitive testing to develop and evaluate CAHPS 1.0 core survey items. Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study. Med Care. 1999;37(suppl 3):MS10–MS21. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199903001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duffy FD, Gordon GH, Whelan G, et al. Assessing competence in communication and interpersonal skills: The Kalamazoo II report. Acad Med. 2004;79:495–507. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200406000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Sullivan P, Chao S, Russell M, et al. Development and implementation of an objective structured clinical examination to provide formative feedback on communication and interpersonal skills in geriatric training. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1730–1735. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turner JL, Dankoski ME. Objective structured clinical exams: A critical review. Fam Med. 2008;40:574–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whelan GP, Boulet JR, McKinley DW, et al. Scoring standardized patient examinations: Lessons learned from the development and administration of the ECFMG Clinical Skills Assessment (CSA) Med Teach. 2005;27:200–206. doi: 10.1080/01421590500126296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim S, Brock DM, Hess BJ, et al. The feasibility of a multi-format Web-based assessment of physicians' communication skills. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;84:359–367. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mazor KM, Haley HL, Sullivan K, et al. The video-based test of communication skills: Description, development, and preliminary findings. Teach Learn Med. 2007;19:162–167. doi: 10.1080/10401330701333357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]