Abstract

In a population-based cohort study of 5014 women with stage 0–III breast cancer, we evaluated weight change patterns from diagnosis to 6, 18, and 36 months post-diagnosis. Patients were recruited to the study approximately 6 months after cancer diagnosis between 2002 and 2006 and followed through 36 months post-diagnosis. The medians of weight change from diagnosis to 6, 18, and 36 months post-diagnosis were 1.0 kg, 2.0 kg, and 1.0 kg, respectively. Approximately 26% of survivors gained ≥5% of their at-diagnosis body weight during the first 6 months after diagnosis, while 37% and 33% of women gained the same percentage of weight at 18 and 36 months post-diagnosis. More weight gain was observed among women who had a more advanced disease stage, were younger, had lower body mass index at diagnosis, were premenopausal, or received chemotherapy or radiotherapy during the first 6 months after cancer diagnosis. Multivariate analyses indicated that age at diagnosis, body size, comorbidity, and disease stage independently predicted weight gain from diagnosis to 36 months post-diagnosis. In summary, weight gain is common over the first 3 years after breast cancer diagnosis among Chinese women. More research is needed to investigate measures to prevent weight gain in breast cancer survivors.

Keywords: weight change pattern, breast cancer, survivor, Chinese population

Introduction

Weight gain is common among women diagnosed with breast cancer in Western countries,1–4 and usually ranges between 1 and 6 kg during the first year after a diagnosis of breast cancer.1, 2, 5–8 Several studies have reported that weight gain is associated with negative effects on health outcomes, such as lower quality of life (QOL) and poor breast cancer prognosis.2, 3, 8–10 Sociodemographic characteristics including age7, 11 and menopausal status1, 4, 7, 11 have been found to be related to weight gain after cancer diagnosis. Although clinical factors such as disease stage and adjuvant treatment have been suggested to increase the risk for weight gain,1, 2, 4, 7, 11 the existing evidence is inconsistent.

To date, most studies on weight change after breast cancer diagnosis have had small sample sizes and have focused on the first year after cancer diagnosis.1, 4, 6, 7, 11–15 Few prospective cohort studies have examined weight change at different time points, such as during the second and the third year after cancer diagnosis, when most women have completed cancer-related treatments. Furthermore, most existing research on weight change has been conducted in Western countries where the prevalence of obesity is relatively high.1, 4, 6, 7, 11–14 Differences in the prevalence of obesity may reflect differences in dietary intake and other lifestyle behaviors between Asian and Western populations, which may translate into different weight change patterns after breast cancer diagnosis. However, to our knowledge, only one report from a small retrospective study of Asian women conducted in Korea has been published. That study found no weight gain after adjuvant treatment among women diagnosed with early stage breast cancer,15 which is inconsistent with previous findings from Western countries.1–4 Characterizing weight change patterns and potential risk factors based on large, population-based, cohort studies would be useful in the development of strategies for weight control among Asian women after breast cancer diagnosis.

In this report, we investigated the patterns of weight change from diagnosis to 6, 18, and 36 months after cancer diagnosis and the potential sociodemographic and clinical risk factors for weight change in a population-based cohort study of Chinese women diagnosed with breast cancer.

Methods

Study setting, subjects, and design

The Shanghai Breast Cancer Survival Study (SBCSS) is a population-based cohort study.16, 17 Through the population-based Shanghai Cancer Registry, 6299 women aged 20–75 years who were newly diagnosed with incident breast cancer between April 1, 2002 and December 31, 2006 were identified and invited to participate in the study approximately 6 months after cancer diagnosis. Overall, 5042 women (80.0%) provided written, informed consent and participated in the first 6 months post-diagnosis in-person interview. The vast majority of study participants (>94%) are Han Chinese. Participants are being followed through additional in-person interviews administered at approximately 18 months, 36 months, and 60 months after cancer diagnosis. Since women diagnosed with stage IV cancer may undergo very different cancer-related treatments compared to women with earlier stage disease, we excluded from the analysis 28 women with TNM stage IV cancer at diagnosis. Therefore, a total of 5014 cases with stage 0–III cancer were included in the current study of weight change. All of study participants were contacted for the 18-month post-diagnosis interview. Of these women, 4554 women completed the 18-month post-diagnosis interview and 100 died before the 18-month post-diagnosis interview. The remaining 360 cases did not participate in the 18-month post-diagnosis interview either because they refused or because they were unavailable during the interview period. After further excluding 10 participants with missing information on weight at the 18-month postdiagnosis interview, 4544 participants remained for the analysis of weight change between diagnosis and 18 months post-diagnosis. The 36-month post-diagnosis interview was completed by 4140 SBCSS participants, and 196 deaths were identified before the interview. After excluding 678 women who refused to be interviewed or were unavailable during the interview period and 3 cases with missing weight information, 4137 cases remained for the analysis of weight gain from 18- to 36-months post-diagnosis. Study participation was volunteer based, and no incentives were used. The SBCSS was approved by the institutional review boards of all institutions involved in this study.

Data collection

Structured questionnaires were administered by trained interviewers through in-person interviews to collect information on sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. Age at diagnosis, education, monthly household income, marital status, menopausal status, menopausal symptoms, lifestyles, and QOL were assessed. Disease- and treatment-related information was collected, including stage of tumor-node metastasis (TNM) at diagnosis, estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) status, type of surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy, and tamoxifen use. In addition, medical charts were reviewed to verify diagnosis, treatment, and disease stage information. ER and PR status were included in the analyses in the following joint categories: ER+/PR+ (receptor-positive), ER−/PR− (receptor-negative), and ER−/PR+ or ER+/PR− (mixed). A Charlson comorbidity index was created based on the validated comorbidity scoring system18 and the diagnostic codes from the International Classification of Disease, 9th revision (ICD-9).19

Anthropometric measurements

Trained staff measured weight at approximately 6, 18, and 36 months after breast cancer diagnosis and height at approximately 6 months after cancer diagnosis. All measurements were taken twice according to a standard protocol. Participants were also asked to report their weight one year before diagnosis and at diagnosis. BMI (weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters) at 6, 18, and 36 months post-diagnosis and weight change from diagnosis to 6, 18, and 36 months post-diagnosis were calculated. Weight at cancer diagnosis was also collected through review of medical charts for 95% of study participants. Overweight and obesity from 1 year pre-diagnosis to 36 months post-diagnosis were categorized according to the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines for international use20 and for Chinese populations.21

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome variable was weight change from cancer diagnosis to 6, 18, and 36 months after diagnosis. Descriptive statistics of weight change were calculated across sociodemographic and clinical factors, including age at diagnosis, education, income, BMI at diagnosis, marital status, menopausal status, menopausal symptoms, comorbidity, relapse/metastasis, cancer-related treatments, ER/PR status, TNM stage, and BMI. Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to estimate the correlation between medical chart-derived and self-reported weight information. Percentage (%) of weight change during the 6, 18, and 36 months after diagnosis was calculated as (100*(weight at specific study time point − weight at diagnosis)/weight at diagnosis).

The t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied to compare differences in weight change by sociodemographic and clinical factors. Multivariate linear analysis was conducted to examine the associations of weight gain with sociodemographic and clinical factors. All factors that were significantly associated with weight change in the univariate analysis were further evaluated in the multivariate models. We adjusted for age at diagnosis, education, and income in the multivariate models to control for age related weight change and the influence of socioeconomic status on weight change. We also conducted additional analyses restricted to women for whom we had weight information abstracted from medical charts and found similar results. All tests were performed by using Statistical Analysis Software (SAS, version 9.1; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina). The significance levels were set at P< 0.05 for two-sided analyses.

Results

Of the 5014 participants, the mean age at diagnosis was 53.5 years (SD: 10.0). Fifty-one percent of women were postmenopausal and 72% reported menopausal symptoms after breast cancer diagnosis. Overall, 20% of participants had serious comorbidities. Approximately 50% of women had ER/PR positive tumors, 28% had ER/PR negative tumors, and 20% had mixed (ER+/PR−, or ER−/PR+) tumors. In total, 37% of women were diagnosed with stage 0-I breast cancer, 49% with stage II, and 9% with stage III. The correlation coefficient between weights obtained from medical chart review and self-reported weight at diagnosis was 0.92. There were no significant differences in sociodemographic or clinical characteristics between women who were included in the current study and those who were not (data not shown).

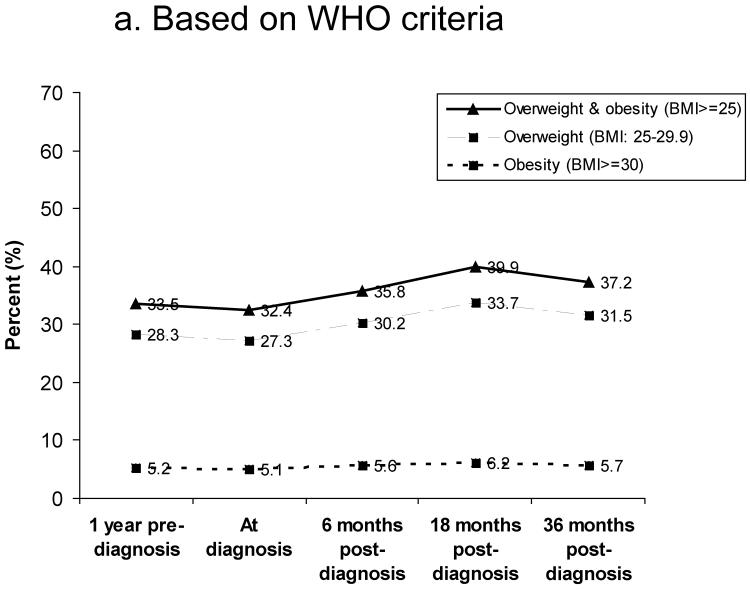

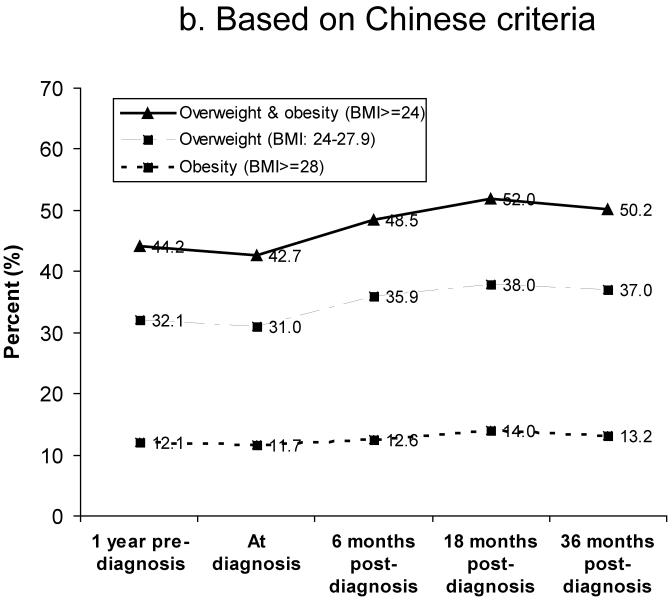

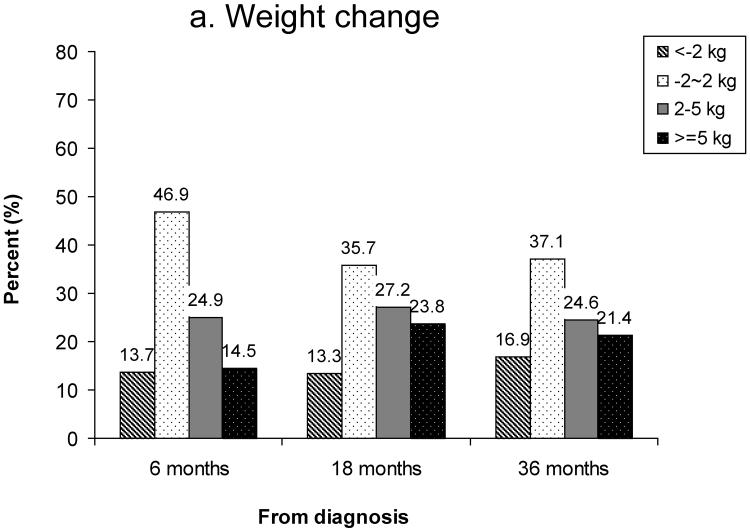

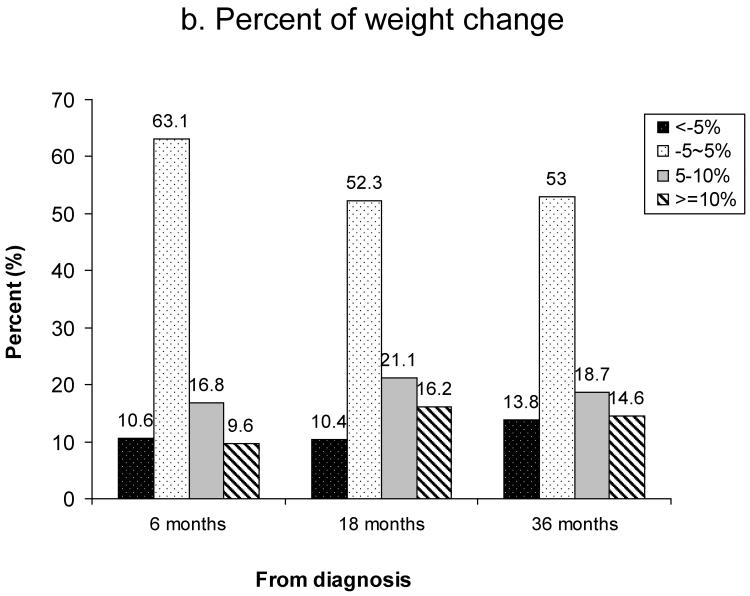

Figure 1 shows the prevalence of overweight and obesity between 1 year pre-diagnosis and 36 months post-diagnosis. Based on WHO criteria, 27% of women were overweight (BMI: 25.0–29.9) and 5% were obese (BMI≥30) at diagnosis (Figure 1a). The prevalence of overweight and obesity at 18 months post-diagnosis was 34% and 6%, respectively. Based on Chinese criteria for overweight and obesity, the rates of overweight (BMI: 24–27.9) and obesity (BMI≥28) were 31% and 12% at diagnosis, 36% and 13% at 6 months post-diagnosis, and 38% and 14% at 18 months post-diagnosis, respectively (Figure 1b). Overall, the number of overweight and obese women increased over the 36 months after diagnosis. Figure 2 summarizes weight change (Figure 2a) and percent of weight change (Figure 2b) from diagnosis to 6, 18, and 36 months after diagnosis for women who had complete weight information during the follow-up surveys. Of these women, 39%, 51%, and 46% gained ≥2kg and 15%, 24%, and 21% gained ≥5kg between diagnosis and 6, 18, and 36 months post-diagnosis, respectively. Overall, 10%, 16%, and 15% of women gained ≥10% of their body weight between diagnosis and the three follow-up surveys, respectively. During the first 6 months post-diagnosis, 14% of women had lost >2kg; this figure changed to 13% at 18 months and 17% at 36 months post-diagnosis (Figure 2a). At 6 months post-diagnosis, 11% of women had lost >5% of their at-diagnosis body weight; this figure changed to 10% at 18 months and 14% at 36 months post-diagnosis, respectively (Figure 2b).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of overweight and obesity between 1 year before diagnosis and 36 months post-diagnosis

a) Based on WHO criteria for overweight and obesity

b) Based on Chinese criteria for overweight and obesity

Figure 2.

Weight change from diagnosis to 6, 18, and 36 months post-diagnosis

a) Weight change

b) Percent of weight change (%)

Table 1 presents the mean weight change from diagnosis to 6 months post-diagnosis stratified by sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. During the 6-month post-diagnosis period, the median weight gain was 0.9 kg. Greater weight gain was observed among breast cancer patients who were younger at diagnosis and who were premenopausal, had a lower comorbidity index, received chemotherapy or radiotherapy, had a more advanced stage of disease, and were underweight at cancer diagnosis. Analyses based on weight information obtained through medical chart review yielded similar results (data not shown).

Table 1.

Weight change from diagnosis to 6 months after breast cancer diagnosis

| Characteristics | N | % | Median (range) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 5014 | 100.0 | 1.0 (−25.0, 20.0) | |

| Age at diagnosis (year) | <0.001 | |||

| <40 | 241 | 4.8 | 2.0 (−7.5, 13.0) | |

| 40–49 | 1999 | 39.9 | 1.5 (−12.5, 18.0) | |

| 50–59 | 1477 | 29.5 | 1.0 (−12.0, 17.0) | |

| ≥60 | 1297 | 25.9 | 0.0 (−25.0, 20.0) | |

| Education | <0.001 | |||

| <High school | 2320 | 46.3 | 1.0 (−25.0, 20.0) | |

| High school | 1889 | 37.7 | 1.0 (−12.5, 18.0) | |

| >High school | 805 | 16.1 | 1.0 (−10.0, 17.0) | |

| Income (yuan/month/capita) | 0.307 | |||

| <1000 | 2874 | 57.3 | 1.0 (−25.0, 20.0) | |

| 1000–1999 | 1540 | 30.7 | 1.0 (−12.0, 15.0) | |

| ≥2000 | 600 | 12.0 | 1.0 (−12.5, 17.0) | |

| Marital status | 0.001 | |||

| Married | 4405 | 87.9 | 1.0 (−25.0, 20.0) | |

| Other | 609 | 12.1 | 0.0 (−12.5, 15.0) | |

| Menopausal status | <0.001 | |||

| Pre-menopausal | 2455 | 49.0 | 1.5 (−12.5, 18.0) | |

| Post-menopausal | 2559 | 51.0 | 0.0 (−25.0, 20.0) | |

| Menopausal symptoms | 0.500 | |||

| No | 1431 | 28.5 | 1.0 (−11.0, 20.0) | |

| Yes | 3583 | 71.5 | 1.0 (−25.0, 18.0) | |

| Charlson comorbidity index | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 4013 | 80.0 | 1.0 (−25.0, 20.0) | |

| 1 | 509 | 10.2 | 0.0 (−11.0, 14.0) | |

| ≥2 | 492 | 9.8 | −0.8 (−12.0, 12.0) | |

| Chemotherapy | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 4570 | 91.1 | 1.0 (−12.5, 20.0) | |

| No | 444 | 8.9 | 0.0 (−25.0, 10.0) | |

| Radiotherapy | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 1605 | 32.0 | 1.0 (−12.0, 20.0) | |

| No | 3409 | 68.0 | 1.0 (−25.0, 16.0) | |

| Immunotherapy | 0.618* | |||

| Yes | 737 | 14.7 | 0.5 (−12.0, 17.0) | |

| No | 4266 | 85.1 | 1.0 (−25.0, 20.0) | |

| Unknown | 11 | 0.2 | 1.0 (−2.0, 8.0) | |

| Tamoxifen use | 0.189* | |||

| Yes | 2610 | 52.1 | 1.0 (−12.0, 20.0) | |

| No | 2401 | 47.9 | 1.0 (−25.0, 17.0) | |

| Unknown | 3 | 0.1 | 1.0 (−1.0, 3.0) | |

| ER/PR status | 0.383* | |||

| ER/PR positive | 2510 | 50.1 | 1.0 (−12.5, 20.0) | |

| ER/PR negative | 1385 | 27.6 | 1.0 (−25.0, 17.0) | |

| ER/PR mixed | 1020 | 20.3 | 1.0 (−12.0, 16.0) | |

| ER/PR unknown | 99 | 2.0 | 1.0 (−6.0, 12.0) | |

| TNM stage | 0.073* | |||

| 0-I | 1836 | 36.6 | 1.0 (−12.0, 16.0) | |

| IIA | 1645 | 32.8 | 1.0 (−25.0, 17.0) | |

| IIB | 837 | 16.7 | 1.0 (−12.0, 15.0) | |

| III | 466 | 9.3 | 1.0 (−12.0, 20.0) | |

| Unknown | 230 | 4.6 | 0.0 (−9.0, 12.0) | |

| BMI at diagnosis** | <0.001 | |||

| Underweight (BMI<18.5) | 205 | 4.1 | 2.0 (−5.0, 12.0) | |

| Normal (BMI: 18.5−23.9) | 2709 | 54.0 | 1.0 (−12.0, 18.0) | |

| Overweight (BMI: 24–27.9) | 1525 | 30.4 | 0.0 (−12.5, 20.0) | |

| Obese (BMI≥28) | 575 | 11.5 | −0.5 (−25.0, 14.5) |

`Unknown' group was excluded from P value test

Based on Chinese criteria for overweight and obesity (ref 21)

Table 2 shows weight change from diagnosis to 18 months after diagnosis. During the 18-month post-diagnosis period, the median weight change was 2.0 kg. Similar to the weight gain pattern for the first 6 months after cancer diagnosis, younger women and premenopausal women gained more weight than older women and postmenopausal women. Women with menopausal symptoms gained more weight than women without menopausal symptoms, while women with more serious comorbidities were more likely to lose weight. Chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and advanced cancer stage were significantly associated with more weight gain. No significant differences in weight change were observed by tamoxifen use or immunotherapy. The percentage of women who used aromatase inhibitors was very low in this study population (<1%), which prevented a detailed analysis.

Table 2.

Weight change from diagnosis to 18 months after breast cancer diagnosis

| Characteristics | N | % | Median (range) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 4544 | 100.0 | 2.0 (−22.0, 22.0) | |

| Age at diagnosis (year) | <0.001 | |||

| <40 | 214 | 4.7 | 3.0 (−11.0, 17.0) | |

| 40–49 | 1792 | 39.4 | 3.0 (−15.0, 22.0) | |

| 50–59 | 1342 | 29.5 | 2.0 (−20.0, 21.0) | |

| ≥60 | 1196 | 26.3 | 0.0 (−22.0, 22.0) | |

| Education | <0.001 | |||

| <High school | 2131 | 46.9 | 1.0 (−22.0, 22.0) | |

| High school | 1708 | 37.6 | 2.0 (−20.0, 22.0) | |

| >High school | 705 | 15.5 | 1.0 (−12.0, 20.0) | |

| Income (yuan/month/capita) | 0.101 | |||

| <1000 | 2612 | 57.5 | 2.0 (−22.0, 22.0) | |

| 1000–1999 | 1404 | 30.9 | 1.0 (−20.0, 22.0) | |

| ≥2000 | 528 | 11.6 | 2.0 (−12.0, 21.0) | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | |||

| Married | 3994 | 87.9 | 2.0 (−20.0, 22.0) | |

| Other | 550 | 12.1 | 1.0 (−22.0, 22.0) | |

| Menopausal status* | 0.002 | |||

| Pre-menopausal | 1214 | 26.7 | 3.0 (−15.0, 22.0) | |

| Post-menopausal | 3330 | 73.3 | 1.0 (−22.0, 22.0) | |

| Menopausal symptoms | 0.032 | |||

| No | 1290 | 28.4 | 1.0 (−19.0, 21.0) | |

| Yes | 3254 | 71.6 | 2.0 (−22.0, 22.0) | |

| Charlson comorbidity index | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 3616 | 79.6 | 2.0 (−20.0, 22.0) | |

| 1 | 477 | 10.5 | 1.0 (−22.0, 22.0) | |

| ≥2 | 451 | 9.9 | 0.0 (−18.0, 16.0) | |

| Relapse/metastasis* | 0.285** | |||

| No | 4370 | 96.2 | 2.0 (−20.0, 22.0) | |

| Yes | 126 | 2.8 | 1.0 (−22.0, 22.0) | |

| Unknown | 48 | 1.1 | 1.0 (−11.0, 18.0) | |

| Chemotherapy | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 4137 | 91.0 | 2.0 (−20.0, 22.0) | |

| No | 407 | 9.0 | 0.0 (−22.0, 15.0) | |

| Radiotherapy | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 1416 | 31.2 | 2.0 (−20.0, 22.0) | |

| No | 3128 | 68.8 | 1.0 (−22.0, 22.0) | |

| Immunotherapy | 0.396** | |||

| Yes | 677 | 14.9 | 2.0 (−16.0, 22.0) | |

| No | 3856 | 84.9 | 2.0 (−22.0, 22.0) | |

| Unknown | 11 | 0.2 | 5.0 (−4.0, 9.0) | |

| Tamoxifen use* | 0.434 | |||

| Yes | 3011 | 66.3 | 2.0 (−20.0, 22.0) | |

| No | 1533 | 33.7 | 2.0 (−22.0, 22.0) | |

| ER/PR status | 0.063** | |||

| ER/PR positive | 2328 | 51.2 | 1.0 (−20.0, 20.0) | |

| ER/PR negative | 1219 | 26.8 | 2.0 (−19.0, 22.0) | |

| ER/PR mixed | 917 | 20.2 | 2.0 (−22.0, 22.0) | |

| ER/PR unknown | 80 | 1.8 | 2.0 (−12.0, 14.0) | |

| TNM stage | 0.001** | |||

| 0-I | 1695 | 37.3 | 1.0 (−22.0, 21.0) | |

| IIA | 1510 | 33.2 | 2.0 (−19.0, 22.0) | |

| IIB | 756 | 16.6 | 2.0 (−20.0, 22.0) | |

| III | 381 | 8.4 | 2.0 (−12.0, 18.0) | |

| Unknown | 202 | 4.5 | 2.0 (−13.0, 15.0) | |

| BMI at diagnosisξ | <0.001 | |||

| Underweight (BMK<18.5) | 179 | 3.9 | 3.0 (−10.0, 16.0) | |

| Normal (BMI: 18.5–23.9) | 2444 | 53.8 | 2.0 (−18.0, 22.0) | |

| Overweight (BMI: 24.0–27.9) | 1388 | 30.6 | 1.0 (−20.0, 20.0) | |

| Obese (BMI≥28) | 533 | 11.7 | −1.0 (−22.0, 22.0) |

Based on information at follow-up interviews.

`Unknown' group was excluded from P value test

Based on Chinese criteria for overweight and obesity (ref 21)

Weight change from diagnosis to 36 months after diagnosis is summarized in Table 3. Women who were younger at diagnosis, had higher income, were premenopausal, received chemotherapy or radiotherapy, or had advanced disease stage were more likely to gain weight. Higher comorbidity index and higher BMI were both significantly related to weight loss.

Table 3.

Weight change from diagnosis to 36 months after breast cancer diagnosis

| Characteristics | N | % | Median (range) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 4137 | 100.0 | 1.0 (−20.0, 27.0) | |

| Age at diagnosis (year) | <0.001 | |||

| <40 | 189 | 4.6 | 3.0 (−19.0, 27.0) | |

| 40–49 | 1619 | 39.1 | 2.0 (−17.0, 23.0) | |

| 50–59 | 1219 | 29.5 | 1.0 (−16.0, 19.0) | |

| ≥60 | 1110 | 26.8 | 0.0 (−20.0, 24.0) | |

| Education | <0.001 | |||

| <High school | 1952 | 47.2 | 1.0 (−20.0, 27.0) | |

| High school | 1545 | 37.4 | 1.0 (−19.0, 23.0) | |

| >High school | 640 | 15.5 | 1.0 (−15.0, 24.0) | |

| Income (yuan/month/capita) | 0.003 | |||

| <1000 | 2373 | 57.4 | 1.0 (−20.0, 27.0) | |

| 1000–1999 | 1284 | 31.0 | 1.0 (−19.0, 18.0) | |

| ≥2000 | 480 | 11.6 | 1.0 (−15.0, 24.0) | |

| Marital status | 0.166 | |||

| Married | 3624 | 87.6 | 1.0 (−19.0, 27.0) | |

| Other | 513 | 12.4 | 1.0 (−20.0, 21.0) | |

| Menopausal status* | <0.001 | |||

| Pre-menopausal | 837 | 20.2 | 2.0 (−19.0, 27.0) | |

| Post-menopausal | 3300 | 79.8 | 1.0 (−20.0, 24.0) | |

| Menopausal symptoms* | <0.001 | |||

| No | 1040 | 25.1 | 1.0 (−20.0, 27.0) | |

| Yes | 3097 | 74.9 | 1.0 (−19.0, 24.0) | |

| Charlson comorbidity index* | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 3336 | 80.6 | 1.5 (−19.0, 27.0) | |

| 1 | 309 | 7.5 | 0.0 (−20.0, 21.0) | |

| ≥2 | 492 | 11.9 | −1.0 (−18.0, 12.0) | |

| Relapse/metastasis* | 0.599** | |||

| No | 3851 | 93.1 | 1.0 (−20.0, 27.0) | |

| Yes | 160 | 3.9 | 1.0 (−19.0, 19.0) | |

| Unknown | 126 | 3.0 | 1.0 (−15.0, 16.0) | |

| Chemotherapy | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 3764 | 91.0 | 1.0 (−20.0, 27.0) | |

| No | 373 | 9.0 | 0.0 (−18.0, 24.0) | |

| Radiotherapy | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 1262 | 30.5 | 2.0 (−19.0, 22.0) | |

| No | 2875 | 69.5 | 1.0 (−20.0, 27.0) | |

| Immunotherapy | 0.816** | |||

| Yes | 609 | 14.7 | 1.0 (−15.0, 18.0) | |

| No | 3518 | 85.0 | 1.0 (−20.0, 27.0) | |

| Unknown | 10 | 0.2 | 2.5 (−7.0, 8.0) | |

| Tamoxifen use* | 0.827 | |||

| Yes | 2706 | 67.1 | 1.0 (−19.0, 27.0) | |

| No | 1325 | 32.9 | 1.0 (−20.0, 20.0) | |

| ER/PR status | 0.281** | |||

| ER/PR positive | 2149 | 52.0 | 1.0 (−19.0, 27.0) | |

| ER/PR negative | 1082 | 26.2 | 1.0 (−20.0, 21.0) | |

| ER/PR mixed | 839 | 20.3 | 1.0 (−17.0, 22.0) | |

| ER/PR unknown | 67 | 1.6 | 1.0 (−17.0, 16.0) | |

| TNM stage | 0.009** | |||

| 0-I | 1587 | 38.4 | 1.0 (−18.0, 24.0) | |

| IIA | 1379 | 33.3 | 1.0 (−20.0, 23.0) | |

| IIB | 661 | 16.0 | 1.0 (−16.0, 20.0) | |

| III | 323 | 7.8 | 2.0 (−19.0, 27.0) | |

| Unknown | 187 | 4.5 | 2.0 (−19.0, 13.0) | |

| BMI at diagnosisξ | <0.001 | |||

| Underweight (BMK<18.5) | 163 | 3.9 | 3.0 (−4.0, 19.0) | |

| Normal (BMI: 18.5–23.9) | 2209 | 53.4 | 2.0 (−13.0, 27.0) | |

| Overweight (BMI: 24.0–27.9) | 1289 | 31.2 | 0.0 (−19.0, 23.0) | |

| Obese (BMI≥28) | 476 | 11.5 | −1.0 (−20.0, 20.0) |

Based on information from the 18 months post-diagnosis interview.

`Unknown' group was excluded from P value test

Based on Chinese criteria for overweight and obesity (ref 21)

Table 4 shows the results of multivariate analysis for weight gain in association with variables which were significantly related to weight gain in univariate analysis. Age at diagnosis, education level, BMI at diagnosis, comorbidity index, and disease stage were significantly and independently associated with weight gain between diagnosis and 36 months post-diagnosis. We did not find that cancer-related treatments were independent predictors for weight gain among breast cancer survivors (data not shown).

Table 4.

Linear regression model: weight gain from breast cancer diagnosis to 36 months post-diagnosis and related factors

| Characteristic | β | SE | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | −0.06 | 0.01 | <0.001 |

| Education (ref: <High school) | |||

| High school | −0.04 | 0.15 | 0.782 |

| >High school | −0.63 | 0.22 | 0.004 |

| BMI at diagnosis | −0.32 | 0.02 | <0.001 |

| Charlson comorbidity index (ref: 0) | |||

| 1 | −0.27 | 0.26 | 0.305 |

| ≥2 | −1.67 | 0.22 | <0.001 |

| TNM stage (ref: 0-I) | |||

| IIA | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.640 |

| IIB | 0.42 | 0.21 | 0.041 |

| III | 0.92 | 0.28 | <0.001 |

Discussion

Our population-based cohort study shows that weight gain is common among Chinese women within 18 months of breast cancer diagnosis and weight gain is sustained afterwards. During the first 6 months after cancer diagnosis, the median weight change was a gain of 1 kg. From diagnosis to 18 months post-diagnosis weight gain was 2.0 kg and from diagnosis to 36 months post-diagnosis was 1.0 kg. Based on Chinese criteria, the prevalence of overweight and obesity were 31% and 12% at diagnosis. It is encouraging to find that women with a higher BMI at diagnosis are more likely to lose weight rather than gain weight after cancer diagnosis, as was observed by Rock et al.11

Weight gain is a big concern for many women after breast cancer diagnosis in Western countries.1, 2, 4–7, 11 McInnes et al.4 found that 63% of US women with early-stage (I–II) breast cancer experienced weight gain at 1 year after adjuvant chemotherapy, and 68% and 40%, respectively, maintained significant weight gain after 2 and 3 years.4 In a study of 535 women with newly diagnosed breast cancer in Canada, Goodwin et al. observed that 84% of women gained weight during the year after adjuvant treatment; the mean weight gain was 1.6 kg in women who received chemotherapy, 1.3 kg in women who received tamoxifen only, and 0.6 kg in women who did not receive adjuvant treatment.1 The Women's Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) Study examined 1116 US women with stage I–IIIA breast cancer and found that the mean weight change was a gain of 2.7kg; 60% of women reported weight gain, 26% reported weight loss, and 14% reported no weight change within the 4-year post-diagnosis period.11 These findings are comparable with what we observed in our Chinese population, although the prevalence of obesity (BMI≥32.2) in the WHEL study was much higher (13.2%) than our study.

To date among Asian populations, only one small retrospective study of weight change after breast cancer diagnosis has been conducted. That study evaluated 260 patients in Korea with stage I–III breast cancer and reported no weight gain after adjuvant treatment.15 The mean weight change in the Korean study was −0.3 kg at 1 year and −0.4 kg at 2 years after cancer treatment, and only 10% of women gained more than 5% of baseline body weight at 1 year,15 which is inconsistent with the findings of studies conducted in Western countries.1, 4, 6, 7, 13, 14 In contrast, our study indicated that 37% of women gained ≥5% of baseline body weight between diagnosis and 18 months post-diagnosis, which is remarkably different from the findings in the Korean population, but consistent with the results of Western studies. Differences in study design, cancer stage, or characteristics of the study populations may account for the discrepancy between our study and the Korean study. Our large, population-based, cohort study suggests that among Chinese breast cancer survivors, despite the relatively low prevalence of obesity, the weight change pattern is similar to that observed in Western populations.

Previous studies have investigated the association of sociodemographic factors with weight change after cancer diagnosis and results have been inconsistent.1, 2, 4, 7, 8, 11, 14, 22, 23 Age has been previously reported as a risk factor for weight change among women with breast cancer.7, 11 In our study, we found that women who were younger at diagnosis were more likely to gain weight than older women. Education was also independently and significantly related to weight gain in our study, consistent with the findings by Rock et al.11

Several biological mechanisms have been proposed for the weight gain observed among breast cancer survivors, including change in menopausal status, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and metabolic rate.1, 2, 11 We observed that premenopausal status was significantly related to more weight gain, which was consistent with previous studies,4, 8, 22 but contradictory to findings from the Health, Eating, Activity, and Lifestyle (HEAL) study.7 In that study, 514 white women diagnosed with 0-IIIA breast cancer in the US were evaluated; more weight gain was observed only among younger postmenopausal women.7 It has been proposed that premenopausal women may be more likely to develop amenorrhea over the course of cancer-related treatments and tend to gain more weight than postmenopausal women.22 However, the menopausal association was attenuated after adjustment for other risk factors in our study.

The association between cancer-related treatments and weight change has been examined with mixed results.1, 7, 8, 11, 15, 22, 23 Tamoxifen use has been linked to more weight gain in some clinical trials24, 25 but not in others.26 In our study, tamoxifen use was not significantly related to weight gain. Some studies conducted in Western countries have shown that chemotherapy is related to weight change.1, 7, 11 For example, in a cohort of 535 women with newly diagnosed breast cancer, Goodwin et al. observed that adjuvant chemotherapy was a strong and independent clinical predictor of weight gain.1 The HEAL study reported that receiving chemotherapy was associated with greater weight gain.7 The Korean study found that women with early stage breast cancer did not gain weight after adjuvant treatment.15 In our study, women who had received chemotherapy or radiotherapy were more likely to gain weight than women who did not. However, the association was no longer significant after adjustment for other factors.

Consistent with the results of the HEAL study,7 we found more weight gain among women with an advanced stage of breast cancer. Earlier research has reported that comorbidities such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease may not be related to weight change.7 However, we found that the existence of serious comorbidity was inversely associated with weight change. Women with more severe comorbidity were more likely to lose weight.

When interpreting our findings, some limitations should be noted. First, weight at one year before diagnosis and at diagnosis were based on self-reports, and misclassification can occur when self-reported weight is used. However, previous validation studies have shown that self-reported weight is accurate,27 and most epidemiological studies have used self-reported weight and weight change.10, 28–30 We observed a high correlation coefficient between self-reported weight at diagnosis and weight from review of medical charts (r=0.92), indicating that self-reported weight is reliable in our study population. Second, no data on body composition change was available, therefore it is difficult to determine whether weight change observed in our study reflects any change in body composition among these breast cancer patients and survivors. The relatively short follow-up period is another limitation. Our ongoing follow-up study will allow us to examine the long-term patterns of weight change after breast cancer diagnosis and the impact of these patterns on breast cancer outcomes.

In summary, our large population-based cohort study indicates that weight gain after a diagnosis of breast cancer is common over the 36-month post-diagnosis period in Chinese population. Age at diagnosis, comorbidity, disease stage, and being underweight at cancer diagnosis are independent predictors for weight gain. Further research is warranted about the effect of modifiable lifestyle factors and genetic variations on weight gain. Appropriate weight control strategies should be developed for women with breast cancer.

Acknowledgements

The content of the information does not necessarily reflect the position or the policy of the US Government, and no official endorsement should be inferred. The authors thank Dr. Fan Jin for her support in study implementation and the participants and staff members of the SBCSS for making this study possible. The authors also thank Drs. Hui Cai and Wanqing Wen for their assistance in statistical analysis and Ms. Bethanie Hull for her assistance in manuscript preparation.

Financial Support: This study was supported by grants from the Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program (DAMD 17-02-1-0607) and the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA118229).

References

- 1.Goodwin PJ, Ennis M, Pritchard KI, McCready D, Koo J, Sidlofsky S, Trudeau M, Hood N, Redwood S. Adjuvant treatment and onset of menopause predict weight gain after breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:120–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demark-Wahnefried W, Rimer BK, Winer EP. Weight gain in women diagnosed with breast cancer. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1997;97:519–26. 29. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(97)00133-8. quiz 27–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chlebowski RT, Aiello E, McTiernan A. Weight loss in breast cancer patient management. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1128–43. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.4.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McInnes JA, Knobf MT. Weight gain and quality of life in women treated with adjuvant chemotherapy for early-stage breast cancer. Oncology nursing forum. 2001;28:675–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodwin PJ. Weight gain in early-stage breast cancer: where do we go from here? J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2367–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.9.2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demark-Wahnefried W, Peterson BL, Winer EP, Marks L, Aziz N, Marcom PK, Blackwell K, Rimer BK. Changes in weight, body composition, and factors influencing energy balance among premenopausal breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2381–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.9.2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Irwin ML, McTiernan A, Baumgartner RN, Baumgartner KB, Bernstein L, Gilliland FD, Ballard-Barbash R. Changes in body fat and weight after a breast cancer diagnosis: influence of demographic, prognostic, and lifestyle factors. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:774–82. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Camoriano JK, Loprinzi CL, Ingle JN, Therneau TM, Krook JE, Veeder MH. Weight change in women treated with adjuvant therapy or observed following mastectomy for node-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:1327–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.8.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kroenke CH, Chen WY, Rosner B, Holmes MD. Weight, weight gain, and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1370–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loi S, Milne RL, Friedlander ML, McCredie MR, Giles GG, Hopper JL, Phillips KA. Obesity and outcomes in premenopausal and postmenopausal breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1686–91. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rock CL, Flatt SW, Newman V, Caan BJ, Haan MN, Stefanick ML, Faerber S, Pierce JP. Factors associated with weight gain in women after diagnosis of breast cancer. Women's Healthy Eating and Living Study Group. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1999;99:1212–21. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(99)00298-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aslani A, Smith RC, Allen BJ, Pavlakis N, Levi JA. Changes in body composition during breast cancer chemotherapy with the CMF-regimen. Breast cancer research and treatment. 1999;57:285–90. doi: 10.1023/a:1006220510597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harvie MN, Campbell IT, Baildam A, Howell A. Energy balance in early breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2004;83:201–10. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000014037.48744.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freedman RJ, Aziz N, Albanes D, Hartman T, Danforth D, Hill S, Sebring N, Reynolds JC, Yanovski JA. Weight and body composition changes during and after adjuvant chemotherapy in women with breast cancer. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2004;89:2248–53. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han HS, Lee KW, Kim JH, Kim SW, Kim IA, Oh DY, Im SA, Bang SM, Lee JS. Weight changes after adjuvant treatment in Korean women with early breast cancer. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2009;114:147–53. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-9984-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Z, Gu K, Zheng Y, Zheng W, Lu W, Shu XO. The use of complementary and alternative medicine among Chinese women with breast cancer. Journal of alternative and complementary medicine (New York, N.Y. 2008;14:1049–55. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu W, Cui Y, Chen X, Zheng Y, Gu K, Cai H, Zheng W, Shu XO. Changes in quality of life among breast cancer patients three years post-diagnosis. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2009;114:357–69. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grunau GL, Sheps S, Goldner EM, Ratner PA. Specific comorbidity risk adjustment was a better predictor of 5-year acute myocardial infarction mortality than general methods. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59:274–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Department of Health and Human Services . The international classification of diseases. 9th rev. ed. U.S Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 1998. Clinical modification, ICD-9-CM. [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization . Report of a WHO consultation of obesity. Geneva: Jun 3–5, 1997. Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou BF. Predictive values of body mass index and waist circumference for risk factors of certain related diseases in Chinese adults--study on optimal cut off points of body mass index and waist circumference in Chinese adults. Biomed Environ Sci. 2002;15:83–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell KL, Lane K, Martin AD, Gelmon KA, McKenzie DC. Resting energy expenditure and body mass changes in women during adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Cancer nursing. 2007;30:95–100. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000265004.64440.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huntington MO. Weight gain in patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for carcinoma of the breast. Cancer. 1985;56:472–4. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850801)56:3<472::aid-cncr2820560310>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoskin PJ, Ashley S, Yarnold JR. Weight gain after primary surgery for breast cancer--effect of tamoxifen. Breast cancer research and treatment. 1992;22:129–32. doi: 10.1007/BF01833342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ingle JN, Twito DI, Schaid DJ, Cullinan SA, Krook JE, Mailliard JA, Tschetter LK, Long HJ, Gerstner JG, Windschitl HE, et al. Combination hormonal therapy with tamoxifen plus fluoxymesterone versus tamoxifen alone in postmenopausal women with metastatic breast cancer. An updated analysis. Cancer. 1991;67:886–91. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910215)67:4<886::aid-cncr2820670405>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fisher B, Costantino J, Redmond C, Poisson R, Bowman D, Couture J, Dimitrov NV, Wolmark N, Wickerham DL, Fisher ER, et al. A randomized clinical trial evaluating tamoxifen in the treatment of patients with node-negative breast cancer who have estrogen-receptor-positive tumors. The New England journal of medicine. 1989;320:479–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198902233200802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spencer EA, Appleby PN, Davey GK, Key TJ. Validity of self-reported height and weight in 4808 EPIC-Oxford participants. Public health nutrition. 2002;5:561–5. doi: 10.1079/PHN2001322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daling JR, Malone KE, Doody DR, Johnson LG, Gralow JR, Porter PL. Relation of body mass index to tumor markers and survival among young women with invasive ductal breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2001;92:720–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010815)92:4<720::aid-cncr1375>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eng SM, Gammon MD, Terry MB, Kushi LH, Teitelbaum SL, Britton JA, Neugut AI. Body size changes in relation to postmenopausal breast cancer among women on Long Island, New York. American journal of epidemiology. 2005;162:229–37. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whiteman MK, Hillis SD, Curtis KM, McDonald JA, Wingo PA, Marchbanks PA. Body mass and mortality after breast cancer diagnosis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:2009–14. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]