Abstract

Purpose

To determine the role age plays in use of intensive care for patients who have major surgery.

Materials and Methods

Retrospective cohort study examining the association between age and admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) for all Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 or older who had a hospitalization for one of five surgical procedures: esophagectomy, cystectomy, pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD), elective open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair (open AAA), and elective endovascular AAA repair (endo AAA) from 2004–08. The primary outcome was admission to an ICU. Secondary outcomes were complications and hospital mortality. We used multi-level mixed-effects logistic regression to adjust for other patient and hospital-level factors associated with each outcome.

Results

The percentage of hospitalized patients admitted to ICU ranged from 41.3% for endo AAA to 81.5% for open AAA. In-hospital mortality also varied, from 1.1% for endo AAA to 6.8% for esophagectomy. After adjusting for other factors, age was associated with admission to ICU for cystectomy (Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) 1.56 (95% CI 1.36–1.78) for age 80–84+; 2.25 (1.85–2.75) age 85+ compared with age 65–69), PD (AOR 1.26 (1.06–1.50) age 80–84; 1.49 (1.11–1.99) age 85+) and esophagectomy (AOR 1.26 (1.02–1.55) age 80–84; 1.28 (0.91–1.80) age 85+). Age was not associated with use of intensive care for open or endo AAA. Older age was associated with increases in complication rates and in-hospital mortality for all five surgical procedures.

Conclusions

The association between age and use of intensive care was procedure-specific. Complication rates and in-hospital mortality increased with age for all five surgical procedures.

Keywords: Aged, Intensive Care Unit, Surgical Procedures, Operative, Triage, Hospital Mortality

The United States population is aging rapidly, with estimates that the number of people over the age of 65 will double by the year 2030 [1]. There is concern regarding an increasing demand for healthcare resources to cope with this aging cohort [2]. Intensive care is one area, in particular, where resources are limited. Already almost half of admissions to intensive care units (ICUs) are for patients over the age of 65, with projected use of intensive care increasing over the next 20–30 years [3, 4].

The use of intensive care for a patient balances estimates of potential benefit gained against the limitations of the resource and preferences of the patient and/or family [5, 6]. The Society of Critical Care Medicine provides “Guidelines for ICU Admission, Discharge, and Triage”. These guidelines acknowledge the difficulty of knowing who will benefit from the ICU, stating that “unfortunately, few studies have examined the indications for and the outcomes of ICU care” [7]. In a review of observational studies that followed all patients who were evaluated to receive intensive care, refusal of ICU admission was associated with age, severity of illness, and medical diagnosis, but there was substantial heterogeneity with regard to the underlying patient populations being studied, as well as the reasons patients were not admitted to the ICU [8].

Among medical patients for whom triage to the ICU is considered, often the diagnosis may be unclear on admission and great variation may exist in the severity of illness between two different patients with the same diagnosis (such as pneumonia). The majority of medical admissions are also unplanned/emergent, causing ICU admission decisions to be made quickly. Moreover, perceptions of futility of care and/or care preferences of patients and families may all be a substantial part of the decision-making. These aspects of medical admissions make them difficult to study as a simple model to determine factors that are associated with use of the ICU.

In contrast, specific surgical patients represent a more homogenous group of patients who have received a clearly defined surgical procedure, often with more time to plan for ICU admission. These patients are less likely to be refused admission to ICU because there are no available beds. Also, they are unlikely to be refused admission due to futility of care, since they were deemed well enough to receive surgery. We therefore examined the use of intensive care for elderly Medicare patients undergoing one of five major surgical procedures to determine the relationship between patient age and use of intensive care.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and data sources

This was a retrospective study using five years of the MedPAR file from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. This dataset contains data on all Medicare hospitalizations from 2004 through 2008. The records contain complete administrative data on in-patient hospitalizations, including patient demographic information, resource utilization, and International Classification of Diseases-Clinical Modification, 9th Revision (ICD-9-CM) diagnostic codes. To collect hospital characteristics in the cohort, we extracted data first from the Centers for Medicare Services Healthcare Cost Report Information System, second from the Prospective Payment System files, and last from American Hospital Association survey from 2007.

Patients and variables

All patients aged 65 or older undergoing five select major surgical procedures during a hospitalization were included in the analysis. The procedures were: esophagectomy, pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD), cystectomy, elective open repair of an abdominal aortic aneurysm (open AAA), and elective endovascular repair of AAA (endo AAA). These surgical procedures were chosen from a larger list of possible procedures after initial inspection of the data because they are (1) commonly performed in patients over the age of 65, (2) well circumscribed and usually not associated with another surgery, and (3) associated with a range of different hospital mortality rates. We obtained procedure information from ICD-9-CM diagnosis and procedure codes (Table e1).

We defined ICU admission using critical care-specific resource utilization codes, including intensive care and/or coronary care. We could not confirm whether intensive care admission definitely occurred after a surgical procedure, rather than before. Therefore, we refer to patients as having received intensive care during the hospitalization. Patient demographics and outcomes were obtained directly from the discharge records. We obtained clinical characteristics using ICD-9-CM diagnoses, and defined comorbidities using the Deyo modification of the Charlson co-morbidity index [9]. As the data are primarily used for billing and administrative purposes, we could not quantify the severity of illness of patients. We identified complications associated with surgery using ICD-9-CM codes (Table e1) [10, 11]. Due to potential variation in use of the “present on admission” indicator, we chose not to use this indicator in generating complications, which is consistent with other studies [12].

Analysis

For analysis of patients with each surgery, we excluded patients cared for in any hospital that (1) did not perform the procedure in Medicare beneficiaries at least 20 times over five years, (2) did not have information on the availability of ICU beds or number of hospital beds, or, (3) admitted either none (0%) or all (100%) of patients to the ICU undergoing the specific procedure (see Figure e1). Of note, the exclusions were performed separately for each surgical procedure so that a hospital could be included in the analysis of some or all surgical procedures.

The primary outcome of interest was admission to intensive care during the hospitalization. Secondary outcomes were percentage of patients with one or more complications, and hospital mortality. We first summarized hospital and patient characteristics and outcomes for each surgical procedure, using percentages, means with standard deviations (±sd), and medians with interquartile ranges (IQR), as appropriate. In the MedPAR file, age is reported in 5 year increments. We grouped together all ages above 85 due to the small number of patients who had surgery over the age of 85.

We examined use of intensive care, complications, and hospital mortality across the five age groups for each surgical procedure. To assess the association between age and use of intensive care, and age and secondary outcomes (one or more complications, and hospital mortality), we performed multi-level mixed-effects logistic regression to identify the odds of ICU admission associated with age. This modeling technique allows for inclusion of patient-level factors, as well as hospital-level factors that might be associated with the decision to admit a patient to the ICU. All listed factors were included in each final multivariate model (see Table e3). Hospital characteristics examined included academic status, size of hospital (number of beds), average daily census, ratio of ICU beds to hospital beds, total volume of surgery performed and of the individual surgical procedure performed (total cases over the five years), and designation as a trauma center. Patient characteristics included age, gender, race, comorbidities, whether the admission was on a weekend or a weekday, and number of complications. We chose to model age as a categorical variable so we did not make assumptions regarding the relationship between the exposure and outcomes. Due to the possibility of co-linearity between age and number of co-morbidities, we directly examined the relationship between age and the number of Charlson co-morbidities using linear regression. We conducted analyses in Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA), Stata 10.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA), and SAS 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Carey, NC, USA). This research involved secondary analyses of de-identified data and was deemed not human subjects research by the Columbia University Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Hospital and patient characteristics

After exclusions (Figure e1) the number of hospitals that performed each surgical procedure ≥ 20 times in a five year period and admitted 1–99% of patients to the ICU ranged from 143 (PD) to 808 (endo AAA) (Table 1). Hospitals that were excluded because they admitted either zero patients or 100% of patients to the ICU for a given surgical procedure were smaller hospitals and performed slightly fewer of each procedure (Table e2). For all procedures, the majority of hospitals were academic (63.2% for endo AAA up to 97.2% for PD), and varied in size. Most hospitals had 5–10% of hospital beds designated as ICU beds. The majority of patients were aged 65–74; patients undergoing endo AAA were the oldest (11.9% were 85+) (Table 2). Many more men than women received these procedures (except for PDs which were evenly distributed between men and women). Most patients (>90%) were Caucasian, and the burden of co-morbidity varied by procedure. Overall use of intensive care ranged from 41.3% for endo AAA to 81.5% for open AAA. Complications were least common among patients undergoing endo AAA (15.4%), and most common among patients who had an esophagectomy (50.3%). There was a consistent inverse association between patient age and the number of Charlson/Deyo co-morbidities (negative regression coefficients) (Table 3), such that patients age 85+ were less likely to have one or more comorbidities compared with patients who were age 65–69 undergoing the same surgical procedure.

Table 1.

Characteristics of hospitals performing each surgical procedure

| Procedures | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Esophagectomy | PD | Cystectomy | Open AAA | Endo AAA | |

| # of hospitals, n | 148 | 143 | 243 | 419 | 808 |

| Academic status, n (%) | |||||

| non-teaching | 12 (8.1) | 4 (2.8) | 36 (14.8) | 136 (32.5) | 297 (36.8) |

| teaching | 136 (91.9) | 139 (97.2) | 207 (85.2) | 283 (67.5) | 511 (63.2) |

| Hospital beds, n (%) | |||||

| <200 | 7 (4.7) | 6 (4.2) | 13 (5.4) | 25 (6.0) | 103 (12.8) |

| 200–399 | 18 (12.2) | 23 (16.1) | 53 (21.8) | 175 (41.8) | 402 (49.8) |

| 400–599 | 53 (35.8) | 49 (34.3) | 94 (38.7) | 130 (31.0) | 192 (23.8) |

| 600–799 | 39 (26.4) | 39 (27.3) | 48 (19.8) | 57 (13.6) | 73 (9.0) |

| 800–999 | 19 (12.8) | 16 (11.2) | 21 (8.6) | 19 (4.5) | 22 (2.7) |

| 1000+ | 12 (8.1) | 10 (7.0) | 14 (5.8) | 13 (3.1) | 16 (2.0) |

| Avg daily hospital census, median (IQR) | 450 (332,614) | 444 (318,608) | 395 (281,524) | 285 (198,441) | 234 (167,364) |

| Total surgeries, median (IQR)* | 10590 (7708–13754) | 10150 (7377–13712) | 8919 (6483–12137) | 6914 (4430–9752) | 5219 (3515–8211) |

| ICU beds, n (%)** | |||||

| <2.5% | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) |

| 2.5–4.9% | 6 (4.1) | 6 (4.2) | 12 (4.9) | 15 (3.6) | 28 (3.5) |

| 5–7.4% | 23 (15.5) | 22 (15.4) | 47 (19.3) | 81 (19.3) | 166 (20.5) |

| 7.5–9.9% | 56 (37.8) | 58 (40.6) | 86 (35.4) | 148 (35.3) | 283 (35.0) |

| 10–12.4% | 32 (21.6) | 29 (20.3) | 45 (18.5) | 82 (19.6) | 168 (20.8) |

| 12.5–<15% | 19 (12.8) | 16 (11.2) | 30 (12.4) | 50 (11.9) | 89 (11.0) |

| ≥15% | 12 (8.1) | 12 (8.4) | 23 (9.5) | 43 (10.3) | 73 (9.0) |

| Trauma Center | |||||

| no | 39 (26.4) | 36 (25.2) | 70 (28.8) | 166 (39.6) | 358 (44.4) |

| yes | 109 (73.7) | 107 (74.8) | 173 (71.2) | 253 (60.4) | 449 (55.6) |

IQR = interquartile range; avg = average

Annual volume of all surgical procedures for each hospital

ICU beds as a percentage of all hospital beds

Table 2.

Characteristics and outcomes of Medicare beneficiaries who had each surgical procedure

| Procedures | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Esophagectomy | PD | Cystectomy | Open AAA | Endo AAA | |

| Patients, n | 7473 | 9213 | 13524 | 22532 | 66982 |

| Age, n (%) | |||||

| 65–69 | 2266 (30.3) | 2298 (24.9) | 3033 (22.4) | 4792 (21.3) | 11083 (16.6) |

| 70–74 | 2310 (30.9) | 2709 (29.4) | 3628 (26.8) | 6095 (27.1) | 15609 (23.3) |

| 75–79 | 1742 (23.3) | 2440 (26.5) | 3668 (27.1) | 6325 (28.1) | 17951 (26.8) |

| 80–84 | 885 (11.8) | 1378 (15.0) | 2384 (17.6) | 3931 (17.5) | 14357 (21.4) |

| 85+ | 270 (3.6) | 388 (4.2) | 811 (6.0) | 1389 (6.2) | 7982 (11.9) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||||

| Male | 5531 (74.0) | 4578 (49.7) | 11047 (81.7) | 16287 (72.3) | 54582 (81.5) |

| Female | 1942 (26.0) | 4635 (50.3) | 2477 (18.3) | 6245 (27.7) | 12400 (18.5) |

| Race, n (%) | |||||

| White | 6804 (91.1) | 8283 (89.9) | 12588 (93.1) | 21144 (93.8) | 63026 (94.1) |

| Black | 298 (4.0) | 514 (5.6) | 538 (4.0) | 798 (3.5) | 2240 (3.3) |

| Other | 371 (5.0) | 416 (4.5) | 398 (2.9) | 590 (2.6) | 1716 (2.6) |

| Charlson/Deyo comorbidities, n (%)* | |||||

| 0 | 4894 (65.5) | 5905 (64.1) | 8451 (62.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 1 | 1412 (18.9) | 1200 (13.0) | 2653 (19.6) | 11067 (49.1) | 32514 (48.5) |

| 2+ | 1167 (15.6) | 2108 (22.9) | 2420 (17.9) | 11465 (50.9) | 34468 (51.5) |

| Admission Day, n (%) | |||||

| Weekday | 6303 (84.3) | 7492 (81.3) | 11768 (87.0) | 19062 (84.6) | 56169 (83.9) |

| Weekend | 1170 (15.7) | 1721 (18.7) | 1756 (13.0) | 3470 (15.4) | 10813 (16.1) |

| ICU Admission, n (%) | 5137 (68.7) | 5516 (59.9) | 6363 (47.1) | 18355 (81.5) | 27640 (41.3) |

| Number of complications** | |||||

| 0 | 3715 (49.7) | 6000 (65.1) | 9459 (69.9) | 12982 (57.6) | 56637 (84.6) |

| 1 | 1824 (24.4) | 2021 (21.9) | 2642 (19.5) | 5364 (23.8) | 7720 (11.5) |

| 2+ | 1934 (25.9) | 1192 (12.9) | 1423 (10.5) | 4186 (18.6) | 2625 (3.9) |

| Hospital Mortality | 506 (6.8) | 367 (4.0) | 324 (2.4) | 1091 (4.8) | 702 (1.1) |

Patients who underwent either open or endovascular AAA by definition had at least one co-morbidity (peripheral vascular disease).

Defined using ICD-9 codes (see Table e1 in the eSupplement for details).

Table 3.

The relationship between age of patients and Charlson/Deyo co-morbidities

| Charlson/Deyo co-morbidities | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedure | Age group | 0 | 1 | 2+ | Mean ±sd | Regression coefficient* | P Value* |

| Esophagectomy | 65–69 | 64.3 | 19.5 | 16.2 | 0.57 ±0.89 | ref | |

| 70–74 | 63.8 | 19.4 | 16.8 | 0.58 ±0.90 | 0.01 (−0.04,0.06) | 0.638 | |

| 75–79 | 65.8 | 18.5 | 15.7 | 0.54 ±0.86 | −0.03 (−0.09,0.02) | 0.243 | |

| 80–84 | 70.7 | 16.6 | 12.7 | 0.45 ±0.79 | −0.12 (−0.19,−0.06) | <0.001 | |

| 85+ | 71.1 | 18.9 | 10.0 | 0.41 ±0.72 | −0.16 (−0.27,−0.05) | 0.004 | |

| PD | 65–69 | 62.5 | 12.6 | 24.9 | 0.69 ±1.01 | ref | |

| 70–74 | 61.5 | 13.3 | 25.2 | 0.72 ±1.04 | 0.03 (−0.02,0.09) | 0.267 | |

| 75–79 | 64.6 | 13.6 | 21.7 | 0.63 ±0.96 | −0.06 (−0.11,0.00) | 0.046 | |

| 80–84 | 67.3 | 13.4 | 19.3 | 0.56 ±0.89 | −0.13 (−0.20,−0.06) | <0.001 | |

| 85+ | 77.1 | 8.2 | 14.7 | 0.40 ±0.79 | −0.29 (−0.39,−0.18) | <0.001 | |

| Cystectomy | 65–69 | 63.3 | 19.5 | 17.3 | 0.59 ±0.91 | ref | |

| 70–74 | 60.2 | 20.5 | 19.3 | 0.65 ±0.93 | 0.06 (0.01,0.10) | 0.013 | |

| 75–79 | 61.8 | 19.3 | 19.0 | 0.62 ±0.91 | 0.03 (−0.01,0.07) | 0.190 | |

| 80–84 | 63.9 | 19.3 | 16.8 | 0.58 ±0.88 | −0.02 (−0.07,0.03) | 0.496 | |

| 85+ | 68.9 | 19.0 | 12.1 | 0.46 ±0.79 | −0.13 (−0.20,−0.06) | <0.001 | |

| Open AAA** | 65–69 | 0.0 | 45.1 | 54.9 | 1.78 ±0.89 | ref | |

| 70–74 | 0.0 | 45.8 | 54.2 | 1.76 ±0.86 | −0.02 (−0.05,0.01) | 0.192 | |

| 75–79 | 0.0 | 48.1 | 51.9 | 1.72 ±0.85 | −0.06 (−0.09,−0.03) | <0.001 | |

| 80–84 | 0.0 | 56.1 | 43.9 | 1.60 ±0.80 | −0.18 (−0.22,−0.15) | <0.001 | |

| 85+ | 0.0 | 62.6 | 37.4 | 1.51 ±0.77 | −0.27 (−0.32,−0.21) | <0.001 | |

| Endo AAA** | 65–69 | 0.0 | 44.7 | 55.3 | 1.88 ±1.00 | ref | |

| 70–74 | 0.0 | 44.8 | 55.2 | 1.86 ±0.97 | −0.02 (−0.04,0.00) | 0.063 | |

| 75–79 | 0.0 | 46.6 | 53.4 | 1.82 ±0.95 | −0.06 (−0.08,−0.04) | <0.001 | |

| 80–84 | 0.0 | 51.7 | 48.3 | 1.72 ±0.89 | −0.17 (−0.19,−0.14) | <0.001 | |

| 85+ | 0.0 | 59.8 | 40.2 | 1.58 ±0.83 | −0.31 (−0.33,−0.28) | <0.001 | |

regression coefficient for relationship between age and Charlson comorbidity score (included as a continuous variable)

The definition of open AAA and endovascular AAA require a diagnosis of peripheral vascular disease, so patients, by definition, have at least one co-morbidity.

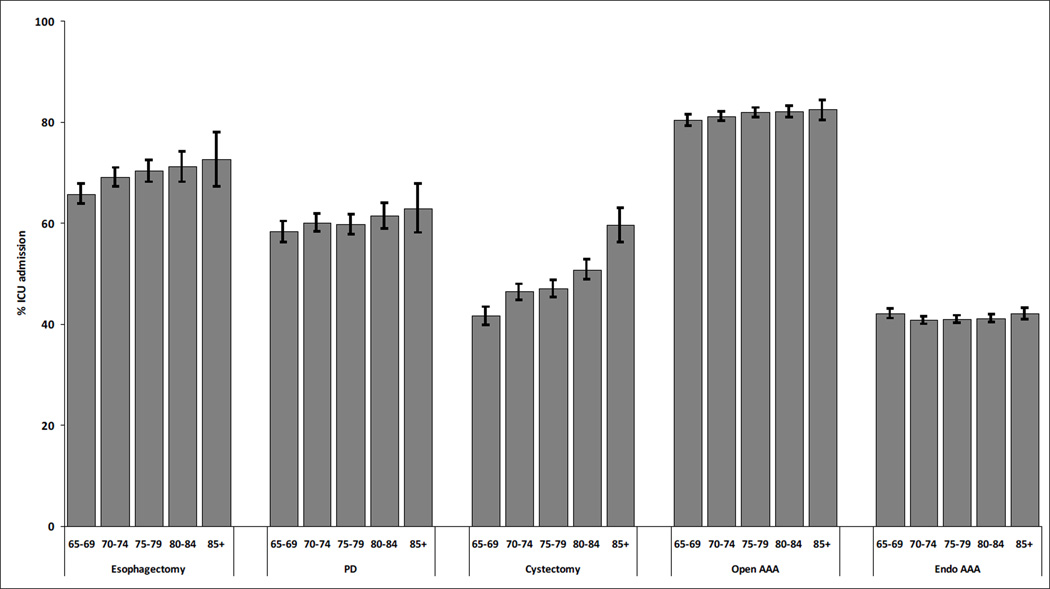

Age and use of intensive care

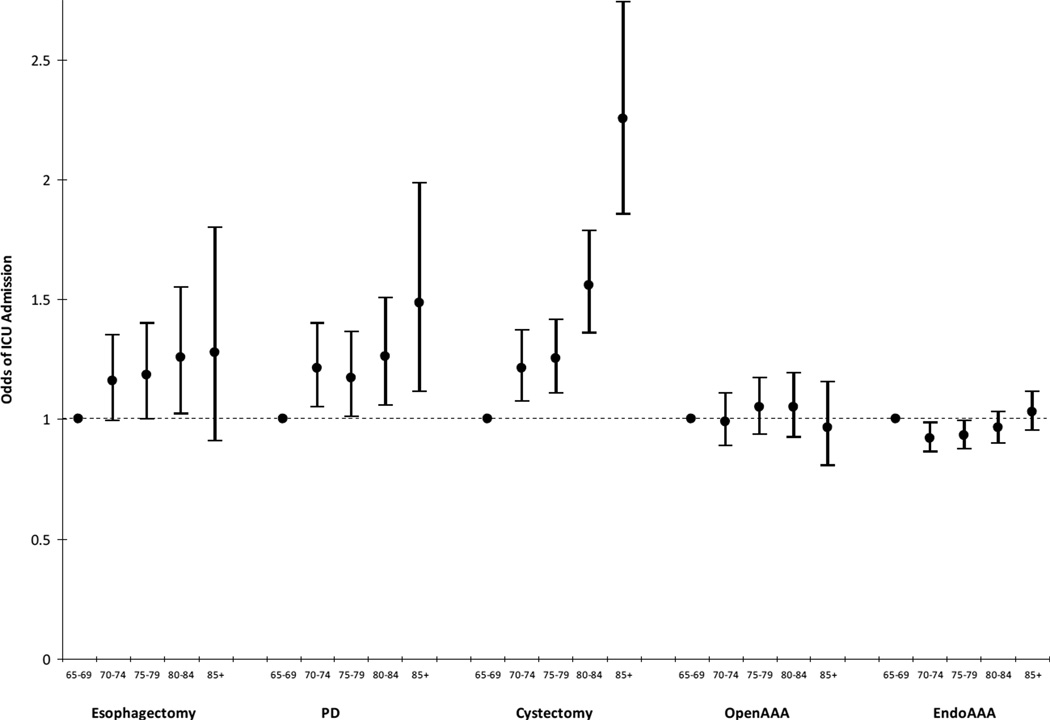

The use of intensive care was positively associated with age for esophagectomies, PDs, and cystectomies, but there was no clear relationship between age and use of intensive care for either open AAA or endo AAA (Figure 1). After adjustment for other patient and hospital-level factors, there was still a strong relationship between age and use of intensive care for cystectomy (Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) 2.25, 95% CI 1.85–2.74, p<0.01 for comparison of patients 85+ with age 65–69) and PD (AOR 1.49, 95% CI 1.11–1.99, p<0.01). For esophagectomy, patients aged 80–84 were more likely to be admitted to the ICU (AOR 1.26, 95% CI 1.02–1.55, p=0.03), but the relationship was not statistically significant for the oldest age group (85+: AOR 1.28, 95% CI 0.91–1.80, p=0.16). The lack of relationship between age and use of intensive care persisted after multivariate adjustment for open AAA and endo AAA (Figure 2; Table e4).

Figure 1.

Percentage of elderly patients admitted to ICU who underwent five different major surgical procedures, with stratification by age of patients

Bars = 95% confidence intervals for percentages

Endo = endovascular; AAA = abdominal aortic aneurysm; PD = pancreaticoduodenectomy

Figure 2.

Adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the association between age and intensive care unit admission for five different major surgical procedures. There was an increased odds of ICU admission with increasing age for patients who had esophagectomies, PD, or cystectomy, and no association for open AAA or endo AAA *

*refer to Methods for list of model covariates

Bars = 95% confidence intervals for percentages

Endo = endovascular; AAA = abdominal aortic aneurysm; PD = pancreaticoduodenectomy

Few hospital factors were strongly associated with the use of intensive care after hierarchical modeling (Table e4). In particular, being a trauma center was associated with a decreased likelihood of admission to ICU for esophagectomy, PD and cystectomy, but not for open AAA or endo AAA. There was also an association between care in a larger hospital (i.e. more beds) and use of intensive care for esophagectomies and open AAA. There was no relationship between the academic status of the hospital and use of intensive care, or the overall availability of ICU beds (as a percentage of hospital beds).

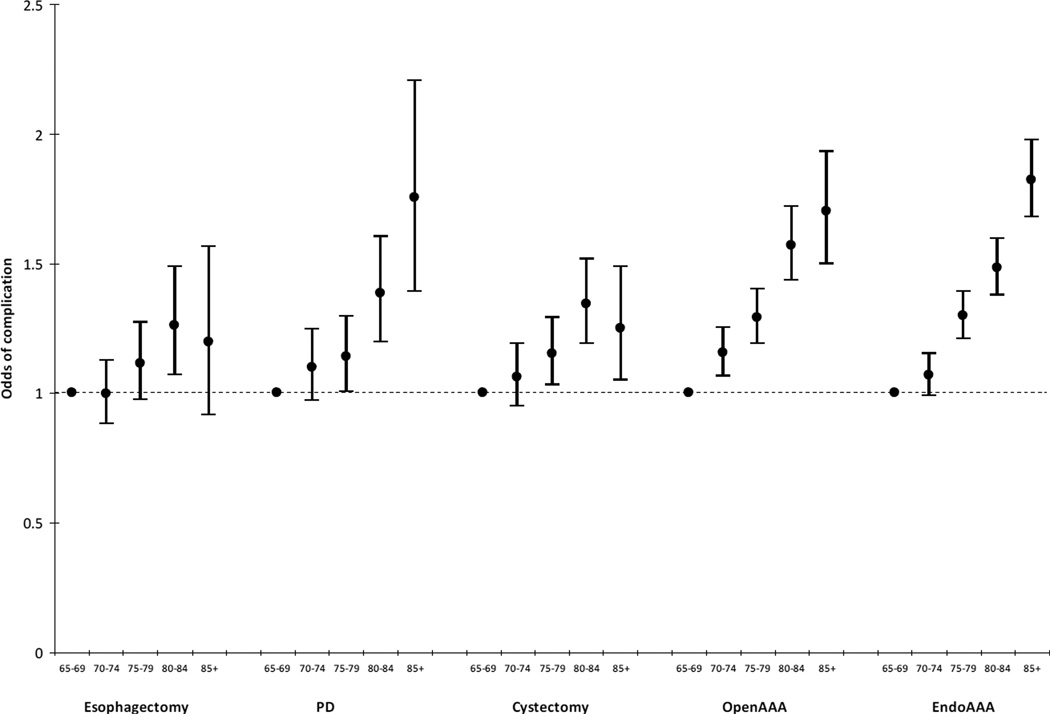

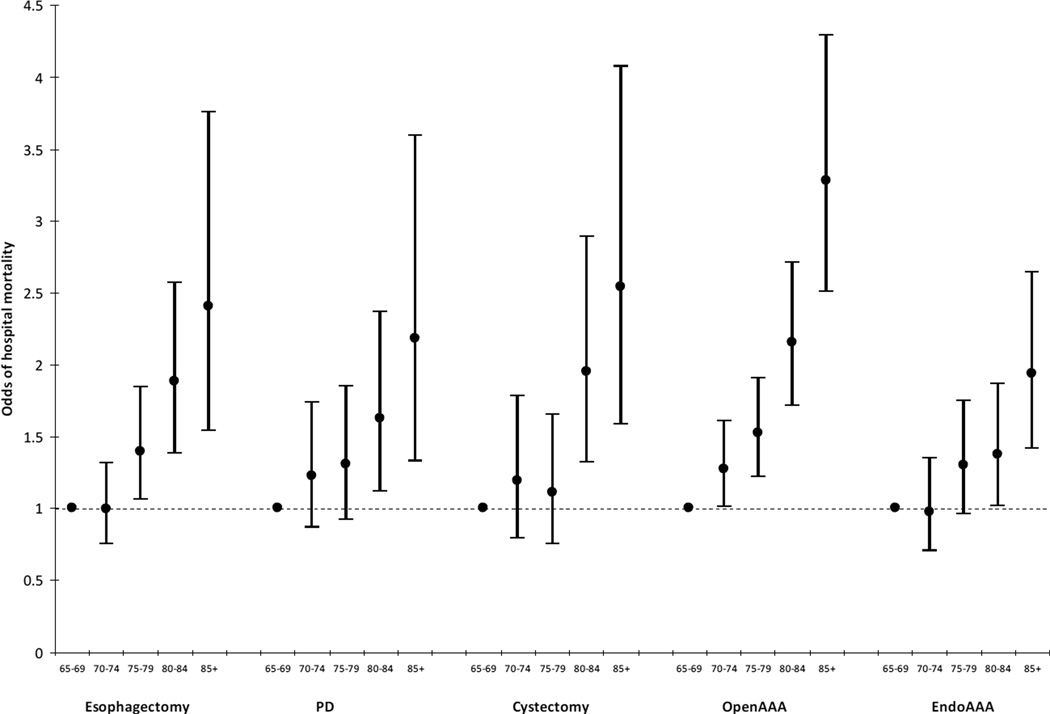

Age, complications and mortality

There was a strong positive correlation between age and complications and age and mortality across all five surgical procedures (data not shown). The association between age and complications remained significant after adjusting for other risk factors for all procedures except esophagectomies – likely due to the small sample size (Figure 3; Table e5). When broken down by type of complication, increasing age was associated with higher complication rates for all of the categories of complications, except infection (which excluded pneumonia) (Tables e6–e10). The association between age and hospital mortality also remained significant across all five surgical procedures (Figure 4; Table e5). The highest odds for hospital mortality was among patients 85+ having an elective open AAA (AOR 3.28, 95% CI 2.51–4.29, p<0.01, compared with patients age 65–69).

Figure 3.

Adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the association between age and the occurrence of one or more complications for five different major surgical procedures. There was a strong association between increasing age and odds of one or more complications for all five procedures.*

*refer to Methods for list of model covariates

Bars = 95% confidence intervals for percentages

Endo = endovascular; AAA = abdominal aortic aneurysm; PD = pancreaticoduodenectomy

Figure 4.

Adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the association between age and hospital mortality for five different major surgical procedures. There was a strong association between increasing age and odds of hospital death for all five procedures.*

*Refer to Methods for list of model covariates

Bars = 95% confidence intervals for percentages

Endo = endovascular; AAA = abdominal aortic aneurysm; PD = pancreaticoduodenectomy

DISCUSSION

These data provide information on the association between age and the use of intensive care using homogenous populations of surgical patients in a national sample. We found a varied association of age with ICU use across surgical procedures. Age was independently associated with admission to the ICU for patients undergoing esophagectomies, PDs and cystectomies, but there was no clear relationship between age and admission to the ICU for either elective open or endo AAA. Whether or not age was a factor in use of intensive care, age was related to the overall hospital mortality associated with the surgical procedure. These findings demonstrate that ICU utilization patterns in surgical patients are not consistent, and are shaped by multilevel factors and vary by the type of surgical procedure.

Recent data show that there is large variation across hospitals with regard to use of intensive care [13, 14]. For example, in a large, national study of admissions to ICUs across US Veterans Affairs hospitals, even after risk adjustment, admission rates for the ICU ranged from 1.6% to 29.5% [14]. Of patients admitted directly to the ICU from the emergency room, 53.2% had a 30-day predicted mortality at admission of 2% or less, and the rate of ICU admission for this low-risk group of patients ranged from 1.2% to 38.9% across hospitals. While some variation is expected, the enormity of the variability suggests that some of it may be unwarranted, and highlights the urgent need to better understand and, perhaps standardize, some admissions practices.

Contrary to the expectation that older patients might be more likely to receive intensive care due to a higher burden of comorbidities, the older patients in our cohort had fewer comorbidities. Our findings also differ from the medical ICU literature, which suggest an increased likelihood of refusal of ICU admission with older age [8]. These finding are likely due to a phenomenon analogous to the “healthy worker effect” [15], namely that people who are able to work are healthier than the general population. In the case of surgical patients, surgeons may only select the extremely fit octogenarians or nonagenarians for surgery, deeming anyone who is both elderly and with severe comorbidities as too “high risk”. In this regard the “refusal” of very elderly patients may be occurring prior to surgery rather than prior to ICU admission.

It is also notable that, despite a lower calculated burden of comorbidities, both post-operative complications and hospital mortality were higher among older patients. One characteristic that is not well captured by Charlson/Deyo comorbidities is that of frailty, defined as a multidimensional syndrome characterized by the loss of physical and cognitive reserve that predisposes to the accumulation of deficits and increases vulnerability to adverse events [16]. Frailty may play a role in the higher morbidity and mortality of more elderly patients, even in the absence of other identifiable underlying disability or comorbidity, and warrants further exploration as a driver of post-operative morbidity and mortality that might need to be quantified and incorporated into ICU admission decisions [17].

There are a number of possibilities as to why age was associated with use of intensive care for some but not all of the surgical procedures examined. The first may be the perceived risk by clinicians (that may or may not be accurate) of the surgery itself – if the perceived risk is either very high or very low, then age may not be viewed as important. Second may be an engrained surgical culture that may vary for each procedure, and have developed differently over time depending on the surgical specialty and invasiveness of the procedure. The third may be that the use of intensive care is high enough for some procedures (such as for open AAA) that it is close to a default for care of patients post-operatively, diminishing the role for age to play in ICU admission practices.

This study has a number of limitations. First, although we chose to use relatively homogenous populations defined by specific surgical procedures, we did not have detailed information on the hospitalizations. In particular, we cannot be sure that admission to the ICU occurred after the surgical procedure (rather than before) or that it occurred directly after the surgical procedure (rather than as a “rescue” measure later in the hospitalization). For all of these procedures it would be unusual for a substantial portion of patients to require intensive care prior to surgery. However, we cannot rule out that, for some select procedures, the greater use of intensive care with older age reflects a rescue pattern of admissions that are occurring later in the hospital stay. Second, although we adjusted for known differences in patient and hospital characteristics, we did not have detailed clinical information on the patients. In particular, because of the limitations of Medicare data, we lacked detailed severity of illness scores; therefore, it is possible that there were unmeasured factors that were associated with the use of intensive care, or that might attenuate the strong relationships found between age and hospital mortality. Third, and perhaps most importantly, we cannot conclude whether greater use of intensive care was associated with a decreased risk of death for patients or attenuated the risk of complications. Therefore, while we can understand the varying relationship between age and use of intensive care across different procedures, we cannot determine from this study alone whether more aggressive use of intensive care among very elderly patients for some of these procedures might result in improved outcomes. Finally, our ability to assess complications was also limited by the use of administrative data. The complications we examined are not all equivalent in terms of severity or their likelihood of prompting an ICU admission, if intensive care is being used as a “rescue” option.

The utility of intensive care for lower risk medical and surgical patients remains questionable [14, 18]. Sparse data on specific low-risk surgical procedures, such as carotid endarterectomies, suggest that routine use of intensive care is not beneficial [19, 20]. Yet, for coronary artery bypass grafting, where mortality is almost as low, routine intensive care is perceived as essential to maintain the low mortality due to the complexity of care required, particularly in the first 24 hours after surgery. Recent data from Europe demonstrated a relatively low use of intensive care in non-cardiac surgery patients with a higher than expected hospital mortality (4%) [21]. However, there was no relationship between the overall use of intensive care and mortality across countries, raising the question of whether morbidity and mortality are actually improved by increased use of intensive care [22].

These data also raise the possibility that demand for intensive care beds for select surgical populations could increase as the population ages. Alternatively, with increasing pressure on beds, some data from the medical literature suggest that decision-making regarding the need for ICU changes, and that goals of care are more likely to be changed [23]. It is possible that as surgical demand increases, practitioners may shift their threshold for admission to ICU, particular without clear data to suggest improved outcomes with ICU in this population.

CONCLUSION

We found that age is inconsistently associated with the use of intensive care for different surgical procedures despite a consistent association of age with an increased risk of complications or death following all of the procedures examined. Whether age is, or should be, routinely included as a factor in ICU admission decisions has been debated [8]. However, knowing the current association between age and use of intensive care is important for the purposes of resource planning. Currently, the average age of critically ill patients in the US is nearly 65 [24]. With the aging of the population, there may be an increase in the need for ICU beds for select post-surgical patients. We must begin to determine whether benefit is gained from greater use of intensive care post-surgery, and consider development of effective alternative care pathways [25].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Funding: Supported by Award Number K08AG038477 from the National Institute on Aging to Dr. Wunsch. The funders had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or in the writing of the manuscript and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The work was performed at Columbia University

Conflicts of interest : None

Author contributions: HW, HG, CG, JR, and GL conception and design; HW, HG and CG analysis of the data; HW, HG, CG, JR and GL interpretation of the data; HW first draft of the manuscript; HW, HG, CG, JR, and GL critical review of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Angus DC, Barnato AE, Linde-Zwirble WT, et al. Use of intensive care at the end of life in the United States: an epidemiologic study. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:638–643. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000114816.62331.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carson SS, Cox CE, Holmes GM, et al. The changing epidemiology of mechanical ventilation: a population-based study. J Int Care Med. 2006;21:173–182. doi: 10.1177/0885066605282784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angus DC, Kelley MA, Schmitz RJ, et al. Caring for the critically ill patient. Current and projected workforce requirements for care of the critically ill and patients with pulmonary disease: can we meet the requirements of an aging population? JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284:2762–2770. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.21.2762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Angus DC, Shorr AF, White A, et al. Critical care delivery in the United States: distribution of services and compliance with Leapfrog recommendations. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1016–1024. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000206105.05626.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Chevret S, et al. Compliance with triage to intensive care recommendations. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:2132–2136. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200111000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wunsch H. A triage score for admission: A holy grail of intensive care. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:321–323. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318236eaa3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guidelines for intensive care unit admission, discharge, and triage. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:633–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinuff T, Kahnamoui K, Cook DJ, et al. Rationing critical care beds: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1588–1597. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000130175.38521.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J ClinEpidemiol. 1992;45:613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCarthy EP, Iezzoni LI, Davis RB, et al. Does clinical evidence support ICD-9-CM diagnosis coding of complications? Med Care. 2000;38:868–876. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200008000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pronovost P, Garrett E, Dorman T, et al. Variations in complication rates and opportunities for improvement in quality of care for patients having abdominal aortic surgery. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2001;386:249–256. doi: 10.1007/s004230100216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghaferi AA, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Complications, failure to rescue, and mortality with major inpatient surgery in medicare patients. Ann Surg. 2009;250:1029–1034. doi: 10.1097/sla.0b013e3181bef697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gershengorn HB, Iwashyna TJ, Cooke CR, et al. Variation in use of intensive care for adults with diabetic ketoacidosis. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:2009–2015. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31824e9eae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen LM, Render M, Sales A, et al. Intensive care unit admitting patterns in the veterans affairs health care system. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2012:1–7. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McMichael AJ. Standardized mortality ratios and the “healthy worker effect”: Scratching beneath the surface. J Occup Med. 1976;18:165–168. doi: 10.1097/00043764-197603000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDermid RC, Stelfox HT, Bagshaw SM. Frailty in the critically ill: a novel concept. Crit Care. 2011;15:301. doi: 10.1186/cc9297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M146–M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zimmerman JE, Kramer AA. A model for identifying patients who may not need intensive care unit admission. J Crit Care. 2010;25:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kraiss LW, Kilberg L, Critch S, et al. Short-stay carotid endarterectomy is safe and cost-effective. Am J Surg. 1995;169:512–515. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80207-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rigdon EE, Monajjem N, Rhodes RS. Criteria for Selective Utilization of the Intensive Care Unit following Carotid Endarterectomy. Annals of Vascular Surgery. 1997;11:20–27. doi: 10.1007/s100169900005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pearse RM, Moreno RP, Bauer P, et al. Mortality after surgery in Europe: a 7 day cohort study. Lancet. 2012;380:1059–1065. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61148-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vonlanthen R, Clavien PA. What factors affect mortality after surgery? Lancet. 380:1034–1036. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61417-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stelfox HT, Hemmelgarn BR, Bagshaw SM, et al. Intensive care unit bed availability and outcomes for hospitalized patients with sudden clinical deterioration. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:467–474. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lilly CM, Zuckerman IH, Badawi O, et al. Benchmark data from greater than 240,000 adults that reflect the current practice of critical care in the United States. Chest. 2011;140:1232–1242. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wunsch H. Is there a starling curve for intensive care? Chest. 2012;141:1393–1399. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.