Abstract

Background

There is little research that has sought to identify factors related to quit success and failure among cannabis users. The current study examined affective, cognitive, and situational factors related to cannabis use among current cannabis users undergoing a voluntary, self-guided quit attempt.

Method

The sample consisted of 30 (33% female) current cannabis users, 84% of whom evinced a current cannabis use disorder. Ecological momentary assessment was used to collect multiple daily ratings of cannabis withdrawal, negative affect, peer cannabis use, reasons for use, and successful coping strategies over two weeks.

Results

Findings from generalized linear models indicated that cannabis withdrawal and positive and negative affect were significantly higher during cannabis use than non-use episodes. Additionally, when negative and positive affect were entered simultaneously, negative affect, but not positive affect, remained significantly related to use. Participants were significantly more likely to use in social situations than when alone. When participants were in social situations, they were significantly more likely to use if others were using. Participants tended to use more behavioral than cognitive strategies to abstain from cannabis. The most common reason for use was to cope with negative affect.

Conclusions

Overall, these novel findings indicate that cannabis withdrawal, affect (especially negative affect), and peer use play important roles in cannabis use among self-quitters.

Keywords: cannabis, marijuana, withdrawal, negative affect, peer influence, ecological momentary assessment

1. INTRODUCTION

Most persons using, abusing, or dependent on cannabis attempt to quit on their own (Copersino et al., 2006). Self-quit is defined as attempts to quit without professional assistance (i.e., enrolling in formal treatment; Copersino et al., 2006). Cannabis self-quit rates are similar to those observed for other substances (e.g., tobacco; Hughes et al., 1996). In fact, by young adulthood, many individuals have made multiple cannabis self-quit attempts. For example, by age 30, weekly cannabis users report 3–7 self-quit attempts (e.g., Copersino et al., 2006; Stephens et al., 1993). Among those undergoing a self-quit attempt, nearly 80% were unable to refrain from cannabis use on over 50% of the days they attempted to abstain (Hughes et al., 2008). Thus, a large proportion of cannabis users is interested in and pursues quitting on their own. Yet, there remains little empirical knowledge about the mechanisms underlying success or failure in quit attempts among self-quitters.

Psychotherapy for cannabis often teaches patients skills to manage ‘high risk’ situations (e.g., Steinberg et al., 2002), including those involving cannabis withdrawal, affect, and peer pressure. Some data indicate these situations are, in fact, related to poorer outcomes. Withdrawal is related to rapid relapse to cannabis dependence among those in cannabis use disorder (CUD) treatment (Cornelius et al., 2008). Negative affect also has been linked to poorer CUD treatment outcomes (e.g., Buckner and Carroll, 2010; White et al., 2004). People report that they often use cannabis in social situations (Buckner et al., 2012a; Reilly et al., 1998) and having more friends who use or approve of cannabis appears to maintain cannabis use (Sussman and Dent, 2004). In fact, in a qualitative interview following quit attempts, participants reported situations involving negative affect and exposure to others smoking cannabis were among the most difficult situations in which to abstain (Hughes et al., 2008). Together, available data suggest that cannabis withdrawal, negative affect, and being in the company of cannabis users may increase the probability of quit failure.

Although research has provided insight into affective and situational correlates of cessation failures, we know little about the proximal correlates of cessation failures due to methodological limitations of extant research. Although several studies (Chen and Kandel, 1998; Hammer and Vaglum, 1990; Kandel and Raveis, 1989) have identified sociodemographic (e.g., age, gender) or lifestyle (e.g., number of substance-using friends) factors related to cannabis cessation, proximal predictors of cessation failures have not been explored. This limitation is unfortunate, as it is unclear whether any risk candidates for cannabis quit failure actually occur during cessation failures. Additionally, although negative affect appears related to cessation failures (e.g., Chen and Kandel, 1998), the time intervals in these studies are often several years, making it unclear whether momentary increases in negative affect are related to cessation failures. Finally, retrospective self-report data of reasons for use during cessation attempts may be subject to memory or recall bias, which could be particularly relevant to cannabis-using populations given evidence of memory problems among users (Wadsworth et al., 2006), particularly heavy users (Pope and Yurgelun-Todd, 1996).

The use of ecological momentary assessment (EMA) is one way to better address these limitations. EMA involves the use of daily monitoring of target behaviors. The benefits of EMA include (Shiffman et al., 2008): (1) data collection in real-world environments; (2) minimization of retrospective recall bias; and (3) aggregation of observations over multiple assessments to facilitate within-subject assessments of behaviors across time and context. We know of only one study using EMA to identify a positive relationship between cannabis craving and use among women receiving treatment for substance dependence (Johnson et al., 2009). Yet, it is unknown whether participants who used cannabis in that study were striving to quit cannabis given that only 34% of the sample were in treatment for cannabis dependence (i.e., some patients may have sought treatment for other substances with no plan to reduce or quit cannabis use).

It also remains unknown what strategies cannabis using individuals find useful to help them remain abstinent during self-quit attempts. High rates of relapse following cannabis treatment and self-quit attempts suggest the need to determine what coping strategies are useful during quit attempts. We are not aware of any studies that assess such strategies during a quit attempt while the individual is actually in the designated ‘high-risk situation.’ One investigation that employed retrospective methodology found that the most useful strategies included keeping busy and exercising (Hughes et al., 2008). It is likely that confirmation of whether such behavioral strategies are actually associated with maintaining abstinence during high-risk situation (e.g., when cannabis cravings are high) as well as identification of additional successful strategies could help inform and improve models of cannabis quitting and guide future treatment development efforts.

The current study sought to determine situational and affective correlates of cannabis use during a quit attempt. Specifically, current cannabis users undergoing a voluntary self-quit attempt were evaluated for two weeks using EMA to record correlates of cannabis use, reasons for use, and strategies employed to maintain abstinence. We first examined whether cannabis withdrawal and/or affect was related to cannabis use. It was predicted that greater cannabis withdrawal and negative (but not positive) affect would be related to use. Second, we examined reasons for cannabis use. Informed by prior work (Hughes et al., 2008), it was hypothesized that coping, conformity, and social motives would be reported during cannabis use episodes. Finally, we examined strategies associated with maintaining cannabis abstinence. In line with retrospective work (Hughes et al., 2008), it was hypothesized that behavioral strategies would be used during periods of elevated cannabis craving.

2. METHOD

2.1 Participants

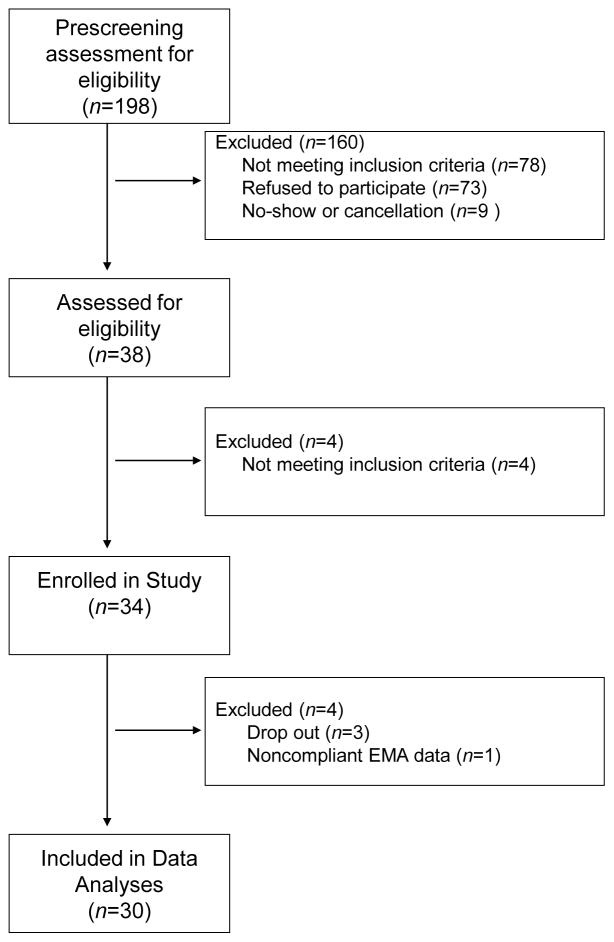

Participants were recruited from August 2010–October 2011 via community advertisements (e.g., flyers, Craigslist advertisements). The sample consisted of current (past-month) cannabis users from the community who (1) endorsed a desire to quit cannabis; (2) expressed intention to quit cannabis on their own (i.e., without the assistance of therapy); (3) agreed to quit cannabis on the date of their first appointment; (4) endorsed cannabis as their drug of choice; and (5) were 18–65 years old. Individuals who were interested in participating first completed an online or telephone screening to assess these inclusion criteria. Of the 47 potential participants who scheduled an appointment, 9 cancelled or no showed. Of the 38 who attended a baseline appointment, 2 were excluded because they met criteria for current alcohol dependence, 1 due to history of delusions, and 1 due to history of hallucinations. Three participants dropped out of the study after baseline appointment and one was excluded due to non-compliance with EMA data collection (described below). Figure 1 presents a flowchart of study participants.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study participants.

The final sample was comprised of 30 (33.3% female) individuals aged 18–50 years (M=22.13, SD=5.96). At baseline, participants reported using cannabis 19–90 (M=66.00, SD=22.72) days in the past 90 days. Mean age of first cannabis use was 15.17 (SD=2.35; range=11–19). The majority (80%) were college students and 20% were employed full-time and 40% employed part-time. The sample was predominantly non-Hispanic/Latino (83.3%) and the racial composition of the sample was: 86.7% Caucasian, 3.3% African American or Black, and 10.0% “mixed”. Regarding prevalence of CUD, 3 (10.0%) met DSM-IV criteria for cannabis abuse and 22 (73.3%) met criteria for cannabis dependence. Per DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), respondents meeting criteria for both abuse and dependence were classified as dependence only. Criteria for a cannabis dependence diagnosis were consistent with DSM-IV with the addition of withdrawal, as proposed for DSM-V (American Psychiatric Association, 2012). The majority (86.7%) met criteria for a current Axis I disorder. Regarding primary diagnoses, cannabis dependence was the most common (63.3%) followed by cannabis abuse (6.7%). Other primary diagnoses included alcohol abuse (3.3%), social anxiety disorder (3.3%), specific phobia (3.3%), obsessive-compulsive disorder (3.3%), and dysthymia (3.3%). Over half (53.3%) met criteria for at least two disorders. Rates of comorbid (i.e., secondary) disorders were as follows: 16.7% alcohol abuse, 13.3% social anxiety disorder, 10.0% cannabis dependence, 6.7% panic disorder, 3.3% cannabis abuse, 3.3% cocaine abuse, 3.3% generalized anxiety disorder, 3.3% specific phobia, 3.3% PTSD, and 3.3% agoraphobia. At baseline, 63.3% endorsed past-month tobacco use and 86.7% endorsed past-month alcohol use.

2.2 Baseline Assessments

Diagnostic status was determined via clinical interview using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (Patient Edition, with psychotic screening module; SCID-I/P [w/Psychotic Screen]; First et al., 2007). Interviews were conducted by trained graduate students in clinical psychology and each was reviewed weekly with a doctoral-level psychologist. In the case of comorbidity, primary diagnoses were determined by ascertaining the most disabling and/or distressing disorder. Diagnostic reliability of CUD diagnoses was established for 20% of randomly selected study participants by comparing the original diagnosis with ratings from trained graduate students blind to initial diagnostic impressions (percent agreement was 86%).

Frequency of cannabis use during the 90 days prior to baseline was assessed with the Timeline Follow Back (Sobell and Sobell, 1996). Participants were asked to report for each day how many cigarette-sized joints of cannabis they used. This measure has demonstrated good test-retest reliability (Fals-Stewart et al., 2000).

2.3 EMA Assessments

EMA data were collected via personal digital assistants (PDAs) that were manufactured by Palm (Z22 Handheld). Assessments were administered on the PDAs through data collection software Satellite Forms 5.2 developed by Pumatech (San Jose, CA). EMA data collection included three types of assessments (Wheeler and Reis, 1991): (1) signal contingent assessments completed upon receipt of semi-random PDA signals presented six times throughout the day; (2) interval contingent assessments completed at bedtime; and (3) event contingent assessments completed each time participants were about to use cannabis. Participants were presented with the same questions regardless of assessment type. They were instructed not to complete assessments when it was inconvenient (e.g., during a religious service) or unsafe (e.g., while driving). Participants were asked to complete assessments in these instances within one hour if possible. The below measures were completed at each assessment.

Craving

Participants were asked if they are currently craving cannabis, and if so, to rate their cannabis craving from 0 (No Urge) to 10 (Extreme Urge). This scale correlates strongly with longer measures of craving (Buckner et al., 2011).

Positive and negative affect

The Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS; Watson et al., 1988) is a 20-item measure of positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA) from 1 (very slightly or not at all) to 5 (extremely). The scales have demonstrated acceptable internal consistency in prior work (Watson et al., 1988) and at baseline in the current sample (PA subscale α=0.81; NA scales α=0.81).

Cannabis withdrawal

The Cannabis Withdrawal Checklist (Budney et al., 2003) assessed severity of cannabis withdrawal from 0 (not at all) to 3 (severe). This scale has shown adequate internal consistency in prior work (Budney et al., 2003) and in the current sample during the monitoring period (α=0.94).

Cannabis use

Participants indicated whether they were about to use cannabis (yes or no). “Yes” responses were considered cannabis use episodes. Frequency of cannabis use using this question was related to retrospective accounts of cannabis use frequency in prior EMA work (Buckner et al., 2012b).

Coping strategies

During non-use episodes, participants were asked what strategies they used to remain abstinent from cannabis. Coping items (see Table 1) were adapted from strategies reported by tobacco smokers during a quit attempt (O’Connell et al., 2007).

Table 1.

Frequency and Proportion of Coping Strategies and Noncoping Responses used during Non-Cannabis Use Episodes

| Total | During Elevated Cannabis Craving | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| N | % of times coping strategies used | N | % of times coping strategies used | |

| Behavioral Strategies | ||||

| Keeping busy | 857 | 49.6 | 123 | 48.2 |

| Eating or drinking | 127 | 7.3 | 13 | 5.1 |

| Deep breathing | 33 | 1.9 | 5 | 2.0 |

| Oral nonfood | 30 | 1.7 | 2 | 0.8 |

| Avoid/leave situation | 103 | 6.0 | 18 | 7.1 |

| Movement/exercise | 135 | 7.8 | 28 | 11.0 |

| Any behavioral strategy | 944 | 54.6 | 140 | 54.9 |

|

| ||||

| Cognitive Strategies | ||||

| Prohibit self from using | 321 | 18.6 | 46 | 18.0 |

| Encouraging/calming self-talk | 62 | 3.6 | 21 | 8.2 |

| Thinking about negatives of using | 122 | 7.1 | 11 | 4.3 |

| Thinking about positives of quitting | 116 | 6.7 | 6 | 2.4 |

| Focusing thoughts away from using | 159 | 9.2 | 26 | 10.2 |

| Optimism about success in quitting | 82 | 4.7 | 11 | 4.3 |

| Total number of cognitive strategies | 469 | 27.1 | 57 | 22.4 |

| Any coping strategy | 1,097 | 63.5 | 152 | 59.6 |

|

| ||||

| Noncoping Responses | ||||

| Wait it out | 248 | 14.4 | 81 | 31.8 |

| No coping | 445 | 25.8 | 68 | 26.7 |

| Any noncoping responses | 601 | 34.8 | 91 | 35.7 |

Note. Elevated craving was operationalized as craving ratings >4 (i.e., at least moderate).

Reasons for cannabis use

The 25-item Marijuana Motives Measure (MMM; Simons et al., 1998) was modified such that participants were asked to check a box next to each item that corresponded with their reason for using cannabis during use episodes. The MMM has demonstrated good internal consistency and concurrent validity (Chabrol et al., 2005; Simons et al., 1998; Zvolensky et al., 2007).

Situation type and others’ cannabis use

Consistent with prior work (Buckner et al., 2012a), participants were asked to choose whether they were in a “Social Situation (with other people)” or “Alone (not in a situation with other people)”. If Social Situation was selected, participants were asked if other people were using or about to use cannabis.

2.4 Procedure

Study procedures were approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained prior to data collection. Participants underwent the clinical interview then completed a battery of computerized self-report measures. A urine sample was collected to confirm current cannabis use. Samples were analyzed quantitatively using a 50 ng/ml positive cutoff.

Participants were then trained on the use of their PDA and given printed instructions of how to use the PDA for their reference during the monitoring period. Consistent with other EMA protocols (e.g., Crosby et al., 2009), participants completed two days of practice data then returned to the lab where feedback was given to participants regarding compliance. Participants then completed EMA assessments for two weeks. A two-week timeframe was chosen given prior work finding this timeframe to be sufficient to monitor substance use behaviors (Buckner et al., 2012a; Freedman et al., 2006). Participants were paid $25 for completing the baseline assessment and $100 for each week of EMA data completed. As in prior work (e.g., Crosby et al., 2009), a $25 bonus was given to participants who completed at least 85% of the random prompts during the two-week monitoring period. Upon completion of the monitoring period, participants were debriefed and provided a list of local mental health treatment referrals.

2.5 Data Analytic Plan and Compliance

Generalized linear models with a logistic response function were used to evaluate whether cannabis withdrawal or affect (positive, negative) was related to cannabis use at each time point. All models included a random effect for subject and fixed effects for other predictors. Pseudo R-squared values were calculated using error terms from the unrestricted and restricted models as described by Kreft and de Leeuw (1998). Compliance with the EMA protocol was assessed by determining mean percentage of random prompts, mean daily percentage of end of day assessments, and mean percentage of both random and end of day assessments completed per participant. Because some participants completed more than two weeks’ worth of data (due to scheduling issues), the first 14 days’ worth of data was retained for these participants. In line with prior work (Buckner et al., 2012a; Hopper et al., 2006), we retained data from participants who completed at least 20% of random prompts (one participant was excluded; Figure 1). Remaining participants completed 65.0% of random signals, 61.7% of end of day assessments, and 64.5% of both random and end of day assessments. These participants completed 1,582 signal contingent (M=53.9, SD=15.5 per participant), 255 interval contingent (M =8.7, SD=3.5 per participant), and 248 event contingent (M=11.6, SD=17.8 per participant) assessments. Signal contingent assessments were completed on average 26.3 (SD =39.6) minutes after the signal occurred.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Patterns of Cannabis Use

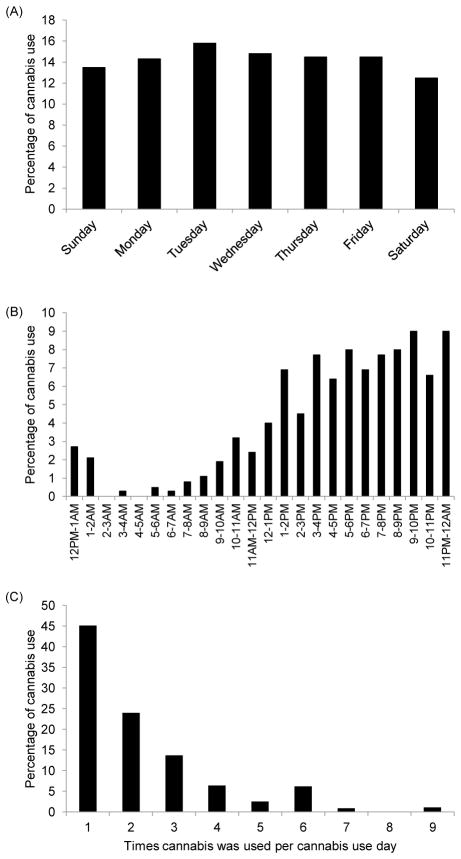

Consistent with their stated intention to quit cannabis, mean number of days of cannabis use was significantly less during the monitoring period (M=12.7, SD=15.2) compared to the two weeks prior to baseline (M=27.7, SD=33.1), t(28)=2.39, p=.020. Despite their intention to quit, however, all but one participant (i.e., 96.6% of the sample) used cannabis during the monitoring period. Specifically, participants recorded 385 cannabis use episodes (range=0–76 per participant). Participants reported an average of 1.1 (SD=1.6) use episodes per day. Figure 2 presents percent of days on which cannabis use occurred (2a), time of day use occurred (2b), and number of times cannabis was used on use days (2c). Interestingly, cannabis use was as likely during the week as on weekends. Most use occurred in the afternoon and evening. When cannabis was used, 54.9% of the time participants reported that they used cannabis more than one time that day.

Figure 2.

(A) Days of the week that cannabis use occurred, (b) time of day when cannabis use occurred, and (C) number of times cannabis used per cannabis use day.

3.2 Cannabis Withdrawal

Cannabis withdrawal was significantly higher during cannabis use (M=4.85, SE=.79) than non-use (M=3.07, SE=.74) episodes, β = 1.78, SE=.32, p < .001. Table 2 lists the specific cannabis withdrawal symptoms endorsed during the monitoring period during cannabis use episodes as well as withdrawal symptoms endorsed as “moderate” or “severe.” Craving was the most commonly reported cannabis withdrawal symptom, experienced during nearly 71% of use episodes. Regarding cannabis withdrawal symptoms rated as “moderate” or “severe,” craving remained the most common symptom followed by NA states such as anxiety, irritability, and anger.

Table 2.

Cannabis Withdrawal Symptoms Endorsed during Cannabis Use Episodes

| % Endorsed at all | % Endorsed as moderate or severe | |

|---|---|---|

| Craving | 70.6 | 39.1 |

| Nervousness/anxiety | 23.1 | 10.3 |

| Irritability | 25.6 | 10.0 |

| Anger | 14.1 | 8.8 |

| Headache | 17.5 | 8.4 |

| Restlessness | 18.8 | 7.5 |

| Depressed mood | 12.8 | 7.5 |

| Increased Aggression | 12.8 | 7.2 |

| Decreased appetite | 12.2 | 7.2 |

| Nausea | 9.1 | 5.6 |

| Shakiness | 15.9 | 5.3 |

| Stomach pains | 8.4 | 4.7 |

| Sweating | 9.4 | 4.4 |

| Strange dreams | 16.6 | 4.1 |

| Sleep difficulty | 10.3 | 4.1 |

3.3 Affect

NA was significantly higher during cannabis use (M=14.22, SE=.59) than non-use (M=12.57, SE=.55) episodes, β = 1.65, SE=.26, p < .001. PA also was significantly higher during cannabis use (M=24.63, SE=1.23) than non-use (M=21.48, SE=1.18) episodes, β = 3.15, SE=.44, p < .001. However, when NA and PA were entered simultaneously, NA (β = 0.04, SE=.01, p=.003), but not PA (β = 0.02, SE=.02, p=.187), remained significantly related to use.

3.4 Peers Influence

Participants were significantly more likely to use cannabis in social situations than when alone, β = 0.80, SE=.21, p < .001. Specifically, 60.6% of cannabis use occurred in social situations. When participants were in social situations, they were significantly more likely to use cannabis if others were using, β = 2.32, SE=.39, p<.001. Specifically, 71.6% of participants’ use in social situations occurred when others were also using.

3.5 Reasons for Use

Reasons for use were examined two ways (see Table 3). First, we examined the most common reasons for use at the item-level. The most common reason for cannabis use was “to cheer up when I’m in a bad mood,” followed by “it’s exciting,” “to be more open to experiences,” and “to fit in with the group I like.” Next, the percentage of use for MMM categories was examined. Nearly half of cannabis use occurred for coping motives. Expansion motives were the next most common reasons for cannabis use, followed by enhancement motives, conformity motives, and, lastly, social motives.

Table 3.

Reasons for Cannabis Use during Cannabis Use Episodes

| Reason for Use | % Endorsement |

|---|---|

| Coping Motives | 47.5 |

| To forget my worries. | 8.6 |

| Because it helps me when I feel depressed or nervous. | 6.2 |

| To cheer me up when I am in a bad mood. | 37.9 |

| To forget about my problems. | 14.3 |

| Because I feel more self-confident and sure of myself. | 4.4 |

| Social Motives | 15.6 |

| Because it helps me enjoy a party. | 3.1 |

| To be sociable. | 9.6 |

| Because it makes social gatherings more fun. | 1.3 |

| Because it improves parties and celebrations. | 1.0 |

| To celebrate a special occasion with friends. | 3.6 |

| Conformity Motives | 23.6 |

| Because my friends pressure me to use cannabis. | 1.0 |

| So that others won’t kid me about not using cannabis. | 5.2 |

| To fit in with the group I like. | 19.7 |

| To be liked. | 1.0 |

| So I won’t feel left out. | 1.3 |

| Enhancement Motives | 32.2 |

| Because I like the feeling. | 0.3 |

| Because it’s exciting. | 28.8 |

| To get high. | 7.5 |

| Because it gives me a pleasant feeling. | 2.6 |

| Because it’s fun. | 0.0 |

| Expansion Motives | 35.3 |

| To know myself better. | 2.6 |

| Because it helps me be more creative and original. | 9.1 |

| To understand things differently. | 3.6 |

| To expand my awareness. | 1.8 |

| To be more open to experiences. | 24.4 |

3.6 Types of Coping

Table 1 lists the coping strategies used to refrain from using cannabis during the monitoring period for all non-use episodes as well as for those non-use episodes during which participants reported at least moderate (≥5) cannabis craving. Participants tended to use more behavioral than cognitive strategies. The most common strategy was “keeping busy.” Movement/exercise and the cognitive strategies of prohibiting oneself from using and focusing thoughts away from using also were popular. Non-coping responses (i.e., waiting it out) also frequently occurred, even during times of elevated craving. Participants used at least one behavioral strategy 54.6% of the times they refrained from use, one cognitive strategy 27.1% of the times they refrained from use, and one non-coping response 34.8% of the time they refrained from use. During periods of elevated cannabis craving, participants used at least one behavioral strategy 54.9% of the times they refrained from cannabis use, one cognitive strategy 22.4% of the times they refrained from use, and one non-coping response 35.76% of the time they refrained from use.

4. DISCUSSION

The present investigation explored affective, cognitive, and situational factors related to cannabis use among current cannabis users undergoing a voluntary, self-quit attempt. Despite their intentions to abstain from cannabis, all but one participant used cannabis during the two week monitoring. This finding adds to the limited empirical literature (e.g., Hughes et al., 2008) illustrating the difficulty many users face in meeting their cannabis cessation goals during self-quit attempts.

The present investigation yielded a number of novel observations. First, cannabis withdrawal was proximally related to cannabis use during the quit attempt. Consistent with existing research (e.g., Budney et al., 1999), craving was the most commonly experienced withdrawal symptom, followed by NA states related to abstinence such as anxiety and irritability. These data suggest that cannabis withdrawal plays a formative role in quit success and should continue to be a focus of attention in theoretical and clinical models of cannabis relapse (Budney et al., 1999).

Second, both PA and NA were higher when participants were about to use cannabis. In line with prediction, it is noteworthy that NA (but not PA) was robustly related to cannabis use in multivariate analyses. The relation of NA to cannabis use is consistent with prior retrospective work (Budney et al., 1999) and substance use work more generally (Piasecki et al., 1997). The present finding suggests that theoretical models of cannabis quitting need to consider the role of affect in general, and NA in particular, during cessation attempts. Indeed, the finding that approximately half of cannabis use occurred for coping motives suggests that the desire to decrease NA plays an especially important role in cessation failures.

Third, the present data shed unique light on several situational factors related to cannabis use during quit attempts. Cannabis was as likely to be used during the week as on weekends and most likely to occur later in the day. Interestingly, when cannabis was used, the majority of the time participants reported they used cannabis multiple times that day. This finding is consistent with an abstinence violation effect (see Marlatt and Gordon, 1985). Additionally, cannabis use was more likely in social situations than when alone. When participants were in social situations, they were significantly more likely to use if others were using. Further, nearly one-fourth of use occurred for conformity motives. Thus, cannabis use among self-quitters appears to maintain a highly social dynamic. These data suggest that cannabis using persons undergoing cannabis cessation may benefit from skills to help them abstain in the face of social dynamic and perhaps pressure from cannabis-using peers.

Fourth, the present study provides novel insight into reasons for cannabis use during cessation attempts as motives for use were assessed during actual use episodes. Contrary to expectation, social motives were not commonly cited reasons for use. Rather, expansion and enhancement motives were more common reasons for use. Specifically, using “because it’s exciting” and “to be open to more experiences” were cited in approximately one-fourth of use episodes. When considered in light of the finding that almost half of use occurred for coping motives, a possible explanation of this finding is that some people used during periods of NA to increase PA, either because they find use exciting or to be open to experiences that may improve mood. This type of explanation is line with work in which expansion and enhancement motives appear more strongly related to cannabis-related problems than social or conformity motives (e.g., Buckner et al., 2007, 2012c).

Finally, data from the current study provide novel insight into strategies used to help people refrain from cannabis use during self-quit attempts. Specifically, during non-use episodes, participants tended to use behavioral strategies to maintain abstinence. As was the case among smokers undergoing tobacco cessation (O’Connell et al., 2007), the most common strategy used to maintain abstinence was “keeping busy.” Engaging in movement or exercise as well as the cognitive strategies of prohibiting oneself from using and focusing thoughts away from using also were popular (Hughes et al., 2008). Interestingly, non-coping responses (i.e., waiting it out, no coping) also were frequently occurring, even during times of elevated craving. Thus, future work may benefit from exploring the role of education and skills training to facilitate abstinence among those interested in quitting.

Results of the present study should be considered in light of limitations. First, cannabis users interested in self-quit were studied to help prevent interpretative problems related to delivering an intervention and to provide knowledge about self-quitters. Yet, the observed rates of cannabis use were high, preventing the possibility of meaningful examination of factors related to sustained abstinence. Second, the present sample is limited in that it is comprised of a relatively homogenous (e.g., primarily Caucasian) group of adult cannabis users who volunteered to participate in a self-quit study for financial compensation. Relatedly, the relatively small sample suggests replication with a larger, more diverse sample will be an important next step. Third, all data relied on self-report and future work could benefit from employing a multi-method and/or multi-informant approach, such as biological verification of cannabis use during the monitoring period and/or collecting collateral reports of use. Fourth, coping skills were only assessed during non-use episodes and future work assessing coping skills utilized during cannabis use episodes could provide invaluable information regarding which skills may be less effective at maintaining abstinence.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Sources

This research was supported in part by a Faculty Research Grant awarded by the Louisiana State University Office of Research and Economic Development and by NIDA Grant 5R21DA029811-02. These funding agencies had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Contributors

Authors Buckner and Zvolensky designed the study. Buckner wrote the protocol and conducted statistical analyses. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. [accessed on September 27 2012];Cannaibs Use Disorder. 2012 http://www.dsm5.org/ProposedRevision/Pages/proposedrevision.aspx?rid=454.

- Buckner JD, Bonn-Miller MO, Zvolensky MJ, Schmidt NB. Marijuana use motives and social anxiety among marijuana-using young adults. Addict Behav. 2007;32:2238–2252. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Carroll KM. Effect of anxiety on treatment presentation and outcome: results from the Marijuana Treatment Project. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178:493–500. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Crosby RD, Silgado J, Wonderlich SA, Schmidt NB. Immediate antecedents of marijuana use: an analysis from ecological momentary assessment. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2012a;43:297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA, Schmidt NB. Social anxiety and cannabis use: an analysis from ecological momentary assessment. J Anxiety Disord. 2012b;25:297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Silgado J, Schmidt NB. Marijuana craving during a public speaking challenge: understanding marijuana use vulnerability among women and those with social anxiety disorder. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2011;42:104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Zvolensky MJ, Schmidt NB. Cannabis-related impairment and social anxiety: the roles of gender and cannabis use motives. Addict Behav. 2012c;37:1294–1297. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Moore BA, Vandrey RG, Hughes JR. The time course and significance of cannabis withdrawal. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112:393–402. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Novy PL, Hughes JR. Marijuana withdrawal among adults seeking treatment for marijuana dependence. Addiction. 1999;94:1311–1322. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94913114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabrol H, Ducongé E, Casas C, Roura C, Carey KB. Relations between cannabis use and dependence, motives for cannabis use and anxious, depressive and borderline symptomatology. Addict Behav. 2005;30:829–840. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Kandel DB. Predictors of cessation of marijuana use: an event history analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;50:109–121. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JR, Chung T, Martin C, Wood DS, Clark DB. Cannabis withdrawal is common among treatment-seeking adolescents with cannabis dependence and major depression, and is associated with rapid relapse to dependence. Addict Behav. 2008;33:1500–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA, Engel SG, Simonich H, Smyth J, Mitchell JE. Daily mood patterns and bulimic behaviors in the natural environment. Behav Res Ther. 2009;47:181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, O’Farrell TJ, Freitas TT, McFarlin SK, Rutigliano P. The Timeline Followback reports of psychoactive substance use by drug-abusing patients: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:134–144. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Biometrics Research. New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 2007. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition With Psychotic Screen (SCID-I/P W/PSY SCREEN) [Google Scholar]

- Freedman MJ, Lester KM, McNamara C, Milby JB, Schumacher JE. Cell phones for ecological momentary assessment with cocaine-addicted homeless patients in treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006;30:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer T, Vaglum P. Initiation, continuation or discontinuation of cannabis use in the general population. Br J Addict. 1990;85:899–909. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1990.tb03720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopper JW, Su Z, Looby AR, Ryan ET, Penetar DM, Palmer CM, Lukas SE. Incidence and patterns of polydrug use and craving for ecstasy in regular ecstasy users: an ecological momentary assessment study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;85:221–235. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Peters EN, Callas PW, Budney AJ, Livingstone AE. Attempts to stop or reduce marijuana use in non-treatment seekers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;97:180–184. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EI, Barrault M, Nadeau L, Swendsen J. Feasibility and validity of computerized ambulatory monitoring in drug-dependent women. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99:322–326. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Raveis VH. Cessation of illicit drug use in young adulthood. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:109–116. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810020011003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreft I, de Leeuw J. Introducing Multilevel Modeling. Sage Publications Ltd; London: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Gordon JR, editors. Relapse Prevention: Maintenance Strategies in the Treatment of Addictive Behaviors. Guilford Press; New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell KA, Hosein VL, Schwartz JE, Leibowitz RQ. How does coping help people resist lapses during smoking cessation? Health Psychol. 2007;26:77–84. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope HG, Jr, Yurgelun-Todd D. The residual cognitive effects of heavy marijuana use in college students. JAMA. 1996;275:521–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly D, Didcott P, Swift W, Hall W. Long-term cannabis use: characteristics of users in an Australian rural area. Addiction. 1998;93:837–846. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.9368375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Ann Rev Clin Psych. 2008;4:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Correia CJ, Carey KB, Borsari BE. Validating a five-factor marijuana motives measure: relations with use, problems, and alcohol motives. J Couns Psychol. 1998;45:265–273. [Google Scholar]

- Smyth JM, Wonderlich SA, Heron KE, Sliwinski MJ, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, Engel SG. Daily and momentary mood and stress are associated with binge eating and vomiting in bulimia nervosa patients in the natural environment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75:629–638. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline FollowBack User’s Guide: A Calendar Method for Assessing Alcohol and Drug Use. Addiction Research Foundation; Toronto: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg KL, Roffman RA, Carroll KM, Kabela E, Kadden R, Miller M, Duresky D. Tailoring cannabis dependence treatment for a diverse population. Addiction. 2002;97:135–142. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.97.s01.5.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman S, Dent CW. Five-year prospective prediction of marijuana use cessation of youth at continuation high schools. Addict Behav. 2004;29:1237–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth EJ, Moss SC, Simpson SA, Smith AP. Cannabis use, cognitive performance and mood in a sample of workers. J Psychopharm. 2006;20:14–23. doi: 10.1177/0269881105056644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler L, Reis HT. Self-recording of everyday life events: origins, types, and uses. J Pers. 1991;59:339–354. [Google Scholar]

- White AM, Jordan JD, Schroeder KM, Acheson SK, Georgi BD, Sauls G, Ellington RR, Swartzwelder HS. Predictors of relapse during treatment and treatment completion among marijuana-dependent adolescents in an intensive outpatient substance abuse program. Subst Abuse. 2004;25:53–59. doi: 10.1300/J465v25n01_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonderlich SA, Rosenfeldt S, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, Engel SG, Smyth J, Miltenberger R. The effects of childhood trauma on daily mood lability and comorbid psychopathology in bulimia nervosa. J Traum Stress. 2007;20:77–87. doi: 10.1002/jts.20184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Vujanovic AA, Bernstein A, Bonn-Miller MO, Marshall EC, Leyro TM. Marijuana use motives: a confirmatory test and evaluation among young adult marijuana users. Addict Behav. 2007;32:3122–3130. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]