Abstract

3q26 is frequently amplified in several cancer types with a common amplified region containing 20 genes. To identify cancer driver genes in this region, we interrogated the function of each of these genes by loss- and gain-of-function genetic screens. Specifically, we found that TLOC1 (SEC62) was selectively required for the proliferation of cell lines with 3q26 amplification. Increased TLOC1 expression induced anchorage independent growth and a second 3q26 gene, SKIL (SNON), facilitated cell invasion in immortalized human mammary epithelial cells. Expression of both TLOC1 and SKIL induced subcutaneous tumor growth. Proteomic studies demonstrated that TLOC1 binds to DDX3X, which is essential for TLOC1-induced transformation and affected protein translation. SKIL induced invasion through up-regulation of SLUG (SNAI2) expression. Together, these studies identify TLOC1 and SKIL as driver genes at 3q26 and more broadly suggest that cooperating genes may be co-amplified in other regions with somatic copy number gain.

Keywords: Copy number alteration, TLOC1, SEC62, SKIL, 3q26, protein translation, cancer

Introduction

The most common alterations found in cancer genomes are recurrent somatic copy number alterations (SCNAs) (1, 2). Although some of these SCNA harbor known oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes, the gene(s) targeted by most of these SNCAs remain unclear. For example, a recent study of more than 3000 cancer samples identified 158 recurrent SCNAs in several cancer types of which 122 did not harbor a known oncogene or tumor suppressor gene (1).

3q26 has been reported to be amplified in several cancer types including breast, prostate, ovarian, non-small cell lung, and head and neck squamous carcinomas. The distal arm of 3q also contains other oncogene candidates including PIK3CA, SOX2 and TP63 (3–5). However, the analysis of a large number of human cancers showed that the minimal commonly amplified region at 3q26 contains 20 genes, which frequently does not include the neighboring genes PIK3CA, SOX2 or TP63.

Here we applied both gain and loss of function approaches to interrogate the 20 genes resident in the minimal common amplified region of 3q26 for effects on proliferation, anchorage independent growth and invasion. We found two genes that cooperated to confer a tumorigenic phenotype: TLOC1 and SKIL.

Results

3q26 is frequently amplified in ovarian, breast and non-small cell lung cancers

We previously used the GISTIC (Genomic Identification of Significant Targets in Cancer) analytical approach to identify recurrent regions of SCNA in a set of 3131 tumor samples (1). Many of the most frequently amplified regions harbored known oncogenes but the identity of specific driver genes was unknown for several recurrently amplified regions. Specifically, 3q26 was amplified in 22% of these tumor samples and 8.4% tumors harbored focal amplifications, as defined as a region less than half a chromosome arm long. The minimal common amplified region contained 20 protein coding genes. When we investigated the specific cancer types in Tumorscape (6) that harbor this amplicon, we found that 3q26 is amplified in 43.7% ovarian, 31.7% breast and 31.2% of non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLC) (1) (Fig. 1A). When we interrogated the current The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (5547 samples) (2, 7), we found that 3q26 is amplified in lung squamous cell (31.5%), serous ovarian (19.3%), cervical squamous cell (11.8%), head and neck (11.5%), pancreatic (7.1%), uterine corpus endometrial (7.1%) and stomach adenocarcinoma cancers (6.1%).

Figure 1. 3q26 is frequently amplified in ovarian, breast and lung non-small cell cancer.

(A) Copy number plots of the samples in Tumorscape for the q arm of chromosome 3. A vertical line represents each sample where red represents a high chromosomal copy number ratio, blue low and white neutral. Chromosomal bands are shown to the left. Two horizontal blue lines indicate the minimal common amplified region and the genes are listed to the right. (B) Illustration of samples with 3q26 amplification. Samples that did not exhibit copy number gain of the PIK3CA, SOX2 or TP63 locus are shown at the top. The 3q distal regions have been magnified to show the position of these in relation to each other. (C) A summary of the screens performed to identify cancer driver genes residing in the minimal common amplified region of 3q26. (D) Cell lines with normal or amplified levels of 3q26 used for the proliferation screen. The amplification data of each cell line is illustrated as above for panel A. The arrow marks the 3q26 region.

Amplification of 3q26 often extends to include larger regions of 3q. Since PIK3CA, SOX2 and TP63 also reside on 3q, we investigated at what frequency these genes are amplified in conjunction with 3q26. Of over 3000 cancer samples in Tumorscape, 718 (22%) displayed amplification of 3q26. Of these 718 samples, 59 did not include PIK3CA, SOX2 or TP63 (Fig. 1B). To investigate if PIK3CA is mutated at a higher frequency in samples that lack amplification of the minimal common amplified region, we analyzed data from 3953 samples from the TCGA (2) for which both copy number and mutation information were available. We found no significant enrichment of PIK3CA mutations in samples that either harbor or lack amplification of 3q26 (p-value = 0.37, Chi-square test). Together these observations confirm that 3q26 is frequently amplified in several cancer types in a manner that is independent of copy number alterations of PIK3CA, SOX2 or TP63.

Systematic interrogation of 3q26 identifies TLOC1 and SKIL as transforming genes

To identify genes resident in 3q26 that contribute to malignant transformation, we interrogated the function of the genes in the region by performing systematic gain and loss of function studies (Fig. 1C). Specifically, we suppressed or overexpressed each of the 20 genes present in the minimal common amplified region for their effects on proliferation, anchorage independent growth and invasion.

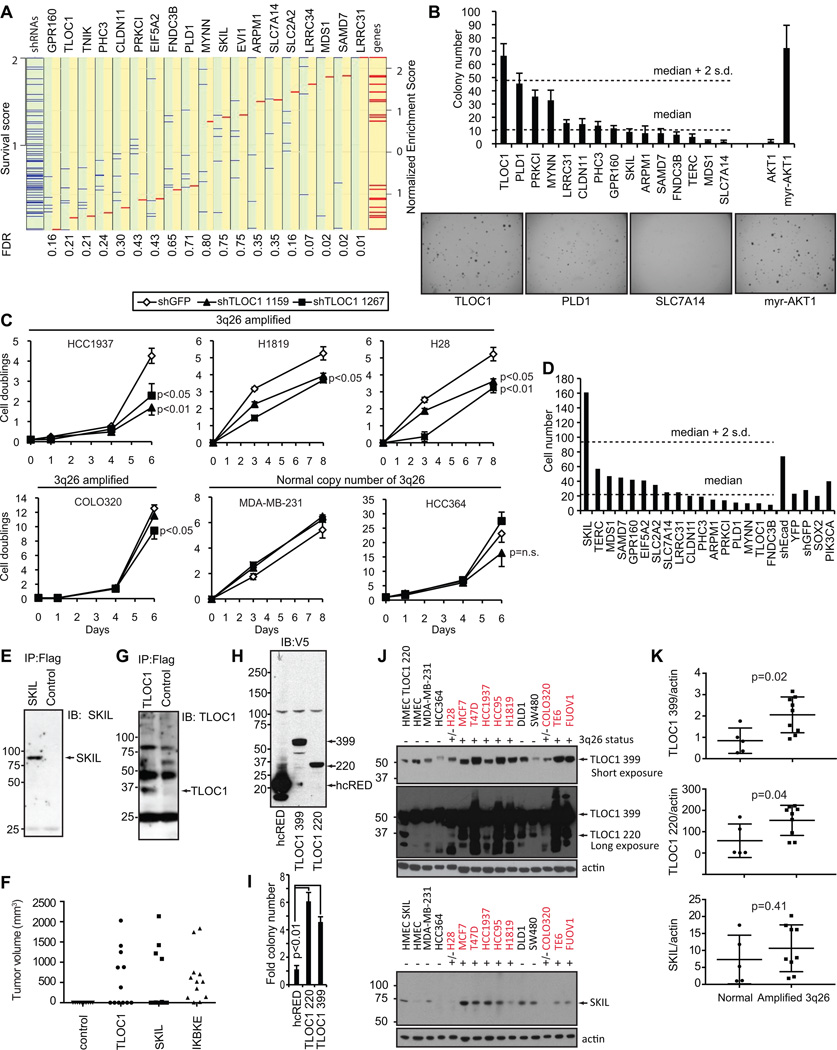

To identify genes whose expression was necessary for the proliferation of cell lines that harbored the 3q26 amplicon, we performed an arrayed short hairpin RNA (shRNA) screen in 11 cell lines that do or 5 cell lines that do not harbor amplification of 3q26 (Fig. 1D). We used RIGER (RNAi Gene Enrichment Ranking) analysis (8) to identify genes that were selectively essential for proliferation of cell lines with 3q26 amplification. This method takes the effect of all shRNAs into account for one gene and compares the score for each gene to other genes. Specifically, we summarized the effects of multiple shRNAs (5 in average) targeting each gene into a single final score called normalized enrichment score (NES), which considers the relative ranking of and the magnitude of gene-specific suppression effects of the shRNAs (Supplementary Table S1). The enrichment score reflects the degree of which the shRNAs targeting each gene are overrepresented at the top or bottom of the ranked list. The scores are further normalized to account for the size of each set of shRNAs against each gene to yield a normalized enrichment score. Using this analysis, we found that suppression of GPR160, TLOC1, TNIK and PHC3 selectively inhibited the proliferation of cells harboring the 3q26 amplification with a False Discovery Rate (FDR) less than 0.25 (Fig. 2A). We confirmed that the degree of gene suppression induced by TLOC1-specific shRNAs correlated with the effects on cell proliferation in cells that harbor 3q26 copy number gain (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Figure 2. Identification of TLOC1 and SKIL as tumor driver genes in 3q26.

(A) RIGER analysis. Differential proliferation scores for each shRNA as compared between cell lines with normal or amplified 3q26 levels are represented by blue lines. Survival scores less than one indicate a relative reduced proliferation in cells with 3q26 amplification. The normalized enrichment score (NES) is represented by a red line and is calculated for each gene based upon the proliferative effect of all shRNAs against that gene. False discovery rates (FDRs) are listed below. All the proliferation effects were normalized against 10 different GFP targeting shRNAs. (B) Anchorage independent growth for HMLE-MEKDD cells expressing each gene from the minimal common region. Each bar shows average number of colonies. Myr-AKT1 was used a positive control. The bottom and top dotted horizontal lines indicate the median and median + S.D. colony number for the tested genes. Representative images of formed colonies are shown below the graph. (C) Effect of TLOC1-specific shRNAs on the proliferation of 4 cell lines with 3q26 amplification and 2 cell lines with diploid 3q26 level. (D) Matrigel induced invasion in HMLE-MEKDD cells overexpressing genes from the common amplified region. The bars indicate the number of invaded cells. The lower dotted horizontal line represents median number of invaded cell and the upper dotted line the median + 2 S.D. (E) Immunoblots for Flag-epitope tagged SKIL immune complexes (IPs) from cells expressing SKIL used (D). (F) Tumor formation of NIH3T3 cells stably expressing control vector (hcRED), TLOC1, SKIL or IKBKE as assessed at 8 wks. (G) Immunoblots for Flag-epitope tagged TLOC1 in Flag-bead immune complexes (IPs) from TLOC1 overexpressing cells used (D). Arrows indicate specific bands. (H) V5-immunoblots for V5-tagged 399 amino acids or 220 amino acids splice variants of TLOC1 and hcRED in HMLE-MEKDD cells. Arrows indicate specific bands. (I) The 220 and 399 amino acids splice variant of TLOC1 significantly induced anchorage independent growth in HMLE-MEKDD as compared to hcRED control (p<0.01, student’s t-test). Bars indicate average fold colony number. (J) Expression levels of endogenous 399 and 220 amino acid forms of TLOC1 in a panel of cell lines. Cell lines with 3q26 amplification are indicated with red text and a (+) sign and cells with normal 3q26 status with black text and a (−) sign. Cell lines that were determined by quantitative real time PCR on genomic DNA to harbor moderately increased copy number of 3q26 are indicated with a (+/−) sign. HMEC cells expressing the short form of TLOC1 were loaded in parallel as immunoblot controls. (K) Comparison in expression levels of the 399 or 220 amino acid forms of TLOC1, or SKIL in cell lines with normal or increased 3q26 copy number (p=0.02, p=0.04, p=0.41 student’s t-test). Plots showing relative expression levels between cell lines with normal or increased 3q26 copy number. The longer parallel bar represent the mean expression and the whiskers S.D. Quantification of TLOC1 and SKIL expression levels relative to actin are from the previous panel. The values are standardized to expression levels in the HMEC cells. n.s. = not significant. Error bars = 1 S.D.

In parallel to these studies, we overexpressed each of the genes in immortalized human mammary epithelial cells (HMLE) expressing an activated allele of MAP2K1 (MEKDD). In prior studies, we showed that these cells (HMLE-MEKDD) do not grow in an anchorage independent manner nor do they form tumors in animals but the expression of oncogenes such as HRAS, AKT1 and IKBKE rendered these cells tumorigenic (9). As such, these cells serve as an experimental model for mammary epithelial transformation. We then assessed the consequences of expressing these genes in two assays, anchorage independent growth and Matrigel invasion, that measure phenotypes associated with malignant transformation.

In the anchorage independent growth assay, TLOC1 was the only gene that induced increased anchorage independent growth in HMLE-MEKDD cells in a manner comparable to that observed when we expressed a myristoylated version of AKT1 (> 2 SD above the median) (Fig. 2B). We note that three genes PLD1, PRKCI and MYNN scored >1 SD over the median.

In addition, we performed proliferation experiments on a set of cell lines that do or do not harbor the 3q26 amplification. By stably expressing shRNAs, we found that cell lines with 3q26 amplification required the expression of TLOC1 for proliferation as compared to cells that lack this amplification (Fig. 2C). We concluded that TLOC1 expression was required for the proliferation of cell lines that harbor the 3q26 amplification.

In contrast, when we assessed whether expression of each of these genes affected the capacity to induce invasion in a trans-well Matrigel invasion assay, we found that SKIL induced significant invasion (Figs. 2D, E, p=0.02; Supplementary Fig. S2), greater than what we observed when we suppressed CDH1 (E-cadherin). These observations identify SKIL as a gene resident in the 3q26 amplicon involved in increased cell invasion.

These observations implicated TLOC1 and SKIL as genes that contribute to distinct cancer phenotypes. To determine whether overexpression of TLOC1 or SKIL sufficed to confer tumorigenic growth to immortalized cells, we overexpressed each of these genes in murine embryo fibroblasts and assessed tumorigenicity in a subcutaneous tumor assay. Similar to what we observed when we expressed the breast cancer oncogene IKBKE in these cells (12 tumors per 12 sites) (9), we found that TLOC1 (6 tumors per 12 sites) and SKIL (6 tumors per 12 sites) induced tumor formation (Fig. 2F). These observations show that TLOC1 and SKIL contribute to tumor initiation and implicate both TLOC1 and SKIL as potential targets of this amplified region.

Expression of TLOC1 and SKIL correlate with 3q26 copy number gain

When we assessed the TLOC1 protein expression in the HMLE-MEKDD cells by immunoblotting, we found that TLOC1 migrated faster than the predicted size of 46 kD (Fig. 2G). We sequenced the construct used in the screen and found that it encoded a novel 220 amino acid version of TLOC1, which represents a splice variant lacking amino acids 182–360 compared to the reported TLOC1 isoform in Ensembl (ENSP00000337688). This splice variant excludes exon 6 and 7 and includes a fusion of exon 5 into the middle of the last exon 8 by intra-exonal splicing (GenBank accession number KC005990). To determine whether this smaller mRNA isoform is expressed in cancer cell lines, we cloned TLOC1 from a T47D cell cDNA library and found both the short (TLOC1 220) and long (TLOC1 399) splice variants of TLOC1 composed of 220 and 399 amino acids, respectively. We also showed that expression of either form in HMLE-MEKDD cells (Fig. 2H) had a similar capacity for inducing a significant anchorage independent growth (p<0.01; Fig. 2I). These observations indicate that the amino acids encoded by exons 6 and 7 are not required for TLOC1-induced transformation.

To investigate whether gene expression or protein levels correlated with amplification status, we performed two analyses. To assess if cell lines that harbor 3q26 amplifications exhibit increased gene expression levels of TLOC1 or SKIL, we performed comparative marker selection using a dataset consisting of cancer cell lines with matched gene expression data and amplification data from the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) (10), which consisted of 967 cancer cell lines. 3q26 amplification was defined as having a log2 copy number ratio over 0.3 for SKIL. From this cell line classification, we then performed a comparative marker selection test, based on a t-test metric, on the gene expression data available for these samples to identify genes that significantly differed between these two classes. We found that TLOC1 and SKIL transcript levels, out of a total of 20,500 transcripts, were the 3rd and 64th highest differentially expressed between cell lines with increased or normal 3q26 copy number, respectively (Supplementary Table S2). These observations confirmed that TLOC1 and SKIL expression levels correlated with amplification of 3q26 in approximately 900 cancer cell lines.

To investigate if 3q26 amplification also correlated with TLOC1 or SKIL protein expression in the cell lines used for our screen, we investigated the TLOC1 and SKIL protein expression in 13 cell lines. We found significantly higher TLOC1 protein expression levels (both TLOC1 399 aa and TLOC1 220 aa) in amplified cell lines as compared to cell lines that harbor normal copy number (p=0.02 and p=0.04; Figs 2J and K). We did not find a strict correlation between SKIL protein levels and SKIL copy number (p=0.41; Figs 2J and K). Specifically, we found that two cell lines (H28 and COLO320) that harbor moderately increased copy number at 3q26 by quantitative real time PCR on genomic DNA, did not exhibit higher expression of SKIL protein (Supplementary Fig. S3). Together these observations confirmed that the transcript levels of TLOC1 and SKIL correlated with 3q26 amplification.

Identification of TLOC1 interacting proteins that are essential for transformation

TLOC1 is part of the translocon complex (11), a channel complex in the ER (endoplasmic reticulum) through which newly synthesized proteins are transported into ER lumen. This complex includes SEC61, TLOC1 and SEC63. TLOC1 and SEC63 have been suggested to recruit newly synthesized polypeptides emerging from the ribosome (12). These observations implicate TLOC1 in co-translational translocation (13). To investigate how TLOC1 induced cell transformation, we isolated TLOC1 interacting proteins by expressing a V5-epitope tagged version of full length TLOC1 in HMLE-MEKDD cells, isolated V5-immune complexes (Fig. 3A), and identified co-immunoprecipitated proteins by mass spectrometry. We found 127 proteins that uniquely precipitated with TLOC1 compared to the unrelated protein Luciferase (Supplementary Table S3). 18 of these proteins were identified by at least 4 unique peptides (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Table S3). The peptide coverage of these 18 proteins ranged from 3% to 33% (Fig. 3B). Of these 18 proteins, four have previously been found as interacting proteins with the Drosophila homolog of TLOC1, Trp1: rb (AP3B1), Trp1 (TLOC1), msk (IPO7) and CGI0077 (DDX5) (Supplementary Table S4). We also identified HSPA5 (Bip, Kar2p), which has previously been described to associate with TLOC1 (14).

Figure 3. DDX3X association with the TLOC1 is essential for TLOC1 induced transformation.

(A) Analysis of co-immunoprecipitated TLOC1 associated proteins visualized by silver or SYPRO staining. The V5-immunoblot shows immunoprecipitated V5-tagged TLOC1 from 2% of the lysate. (B) 18 TLOC1 associated proteins were identified by at least 4 unique peptides. (C) Category distribution of the proteins identified in the mass spectrometry analysis. (D) The effect of suppressing TLOC1 associated proteins on TLOC1-induced anchorage independent growth in HMLE-MEKDD cells. Black bars indicate number of colonies. The upper and lower dashed horizontal lines indicate mean ± 1 S.D., respectively. (E) DDX3X and TLOC1 immunoblots for V5 and DDX3X immune complexes from V5-TLOC1 or V5-Luciferase overexpressing cells. Rabbit IgG was used as a negative control for the DDX3X immunoprecipitation and V5-tagged luciferase for the V5 experiments. (F) Co-immunoprecipitation of DDX3X with different V5-tagged TLOC1 truncation mutants TLOC1 mutants and DDX3X were detected by V5 and DDX3X immunoblotting, respectively. (G) Removal of the 81 first N-terminal amino acids of TLOC1 significantly reduced its ability to induce anchorage independent growth in HMLE-MEKDD cells (p=0.006, student’s t-test). The bars indicate average colony number. YFP and hcRED were used as negative controls. For all panels arrows indicate specific bands for the immunoblots. n.s. = not significant. Error bars = 1 S.D.

When we examined the top 18 identified proteins, we found enrichment in proteins implicated in translation (Fig. 3C and Supplementary Table S3). Specifically, 4 of the 18 proteins have been reported to be involved in translation: HNRNPM, DDX3X, PABPC1 and EIF3CL (15–18). To identify proteins essential for TLOC1-induced cell transformation, we suppressed each of the associated proteins with two independent shRNAs and tested for their effect on anchorage independent growth in TLOC1 overexpressing HMLE-MEKDD cells. Of these candidates, DDX3X and SRRM2 significantly reduced anchorage independent growth (Fig. 3D). Since DDX3X previously has been reported to be involved in translation (17) and gave the strongest phenotype, we focused on DDX3X for subsequent experiments.

To confirm that DDX3X interacted with TLOC1, we re-isolated V5-tagged immune complexes and detected endogenous DDX3X by immunoblotting (Fig. 3E). To identify domains of TLOC1 that were responsible for the association with DDX3X, we generated a set of TLOC1 truncation mutants. These truncation mutants were generated from the 220 amino acid long splice variant of TLOC1 (Fig. 3F). We found that the 81 N-terminal amino acids were necessary for the interaction of TLOC1 with DDX3X. In parallel, we tested the transforming ability of each of these truncation mutants and found that the 81 N-terminal amino acids also were necessary for TLOC1 to induce anchorage independent growth (Fig. 3G). These observations showed that the 81 N-terminal amino acids are required for the association of TLOC1 with DDX3X and for TLOC1-induced cell transformation.

TLOC1 affects cap-dependent versus IRES-independent translation

To assess whether TLOC1 and DDX3X affected protein translation, we manipulated TLOC1 and DDX3X expression and measured the effects on translation using a bi-cistronic translation reporter system. In this system, cap-dependent translation controls renilla luciferase expression and an IRES (Internal Ribosome Entry Site) regulates firefly luciferase expression (19) (Fig. 4A). We found that TLOC1 overexpression significantly reduced IRES-dependent translation (p=0.002), which resulted in a significant net increase of the ratio of cap-dependent to IRES-dependent translation (p=0.01: Fig. 4B). Furthermore, we tested this reporter system with the TLOC1 truncation mutants and found that the full-length form and the shorter C-terminal truncation version significantly inhibited the IRES-dependent translation reporter, whereas the 149 amino acid N-terminal truncation mutant, which does not interact with DDX3X, failed to affect this reporter (Fig. 4C). We also tested if suppression of DDX3X affected translation in cells expressing TLOC1. We found that the increased cap/IRES-dependent translation induced by TLOC1 expression was significantly reversed upon DDX3X suppression (Fig. 4D). Together, these observations show that TLOC1 levels modulate cap/IRES-dependent translation, which is reversed by suppression of DDX3X.

Figure 4. TLOC1 increased the cap versus IRES-dependent translation ratio by decreasing IRES-dependent translation.

(A) Illustration of the bi-cistronic translation reporter used to measure translation levels. The renilla luciferase reporter is driven by cap-dependent translation and the firefly luciferase by IRES-dependent translation. (B) TLOC1 over expression significantly increased the ratio of cap-dependent versus IRES-dependent translation by inhibition of IRES-dependent translation (p=0.01, student’s t-test). The ratio of cap/IRES-dependent translation was calculated and is illustrated in the right graph. (C) Overexpression of the transforming TLOC1 truncation mutant ΔC27 significantly (p=0.03, student’s t-test) inhibited IRES-dependent translation as compared to the non-transforming variant ΔN149. (D) Suppression of DDX3X in TLOC1 overexpressing cells significantly reversed the TLOC1 induced change in translation ratio (p=0.03, student’s t-test). (E) TLOC1 and DDX3X binds to 7-methylated GTP beads, and TLOC1. (F) TLOC1 overexpression increased EIF4G protein expression. (G) TLOC1 overexpression in HMLE-MEKDD cells decreased EIF4EBP1-phosphorylation on Threonine 37.45 and Serine 65. Lysates were prepared from TLOC1 or BFP overexpressing HMLE-MEKDD cells, which had been grown with (+GFs) or without (−GFs) growth factors for 24 hrs. Error bars = 1 S.D.

EIF4E binds to the mRNA cap structure to initiate translation. EIF4G is a scaffold protein that interacts with EIF4E and promotes the assembly of EIF4E and EIF4A (DDX2A) to create the initiation complex EIF4F. EIF4A, like DDX3X is also an RNA helicase. Several other proteins, for example EIF4EBP1, bind to or modify this complex to alter its activity and specificity. Hypophosphorylated EIF4EBP1 is known to inhibit translation by sequestering EIF4E. Phosphorylation of EIF4EBP1 releases EIF4E and allows EIF4E to assemble the EIF4F complex and induce translation (20). EIF4EBP1 phosphorylation levels are regulated by the mTOR pathway.

To determine whether TLOC1 and DDX3X bind translation related complexes, we isolated 7-methylated GTP binding complexes and assessed the associated levels of EIF4E, EIF4G, TLOC1 and DDX3X in HMLE-MEKDD cells expressing TLOC1. We found that all of these proteins bound 7-methylated GTP but not actin or BFP, which served as controls for non-specific binding (Fig. 4E). We also found that TLOC1 overexpression increased EIF4G levels as well as the amount of EIF4G1 associated to the 7-methylated GTP beads (Fig. 4F). These observations show that TLOC1 and DDX3X interact with a translation protein complex through 7-methylated GTP and that TLOC1 overexpression increases EIF4G protein levels as well as the levels of EIF4G that associate with 7-methylated GTP beads.

To investigate if TLOC1 expression had any effects on known regulators of translation, we investigated the phosphorylation status of EIF4EBP1. We found that TLOC1 overexpression led to decreased EIF4EBP1 phosphorylation at threonine 37 and 45 and at serine 65 (Fig. 4G). In aggregate, these observations provide evidence that overexpression of TLOC1 affects the ratio of cap-dependent translation through interactions with proteins involved in regulating protein translation including DDX3X.

SLUG is required for SKIL-induced cell invasion

SKIL has been reported to inhibit the TGF-beta signaling axis by binding to SMAD4 and SMAD2, recruiting the transcriptional co-repressor N-Cor and suppressing SMAD-induced transcription (21). SMAD4 is a tumor suppressor gene frequently inactivated in pancreatic cancer, and has been correlated with an invasive phenotype (22). To determine whether overexpression of SKIL or suppression of SMAD4 induced similar cell states, we analyzed existing gene expression data from the CCLE (10). After downloading the data from CCLE, we calculated the average expression and standard deviation for SKIL and SMAD4 on a set of 634 samples (all CCLE cell lines excluding samples derived from hematological malignancies). High SKIL expression was defined as one SD above average SKIL expression and low SMAD4 expression one SD below average SMAD4 expression. 93 cell lines were identified to have high SKIL expression, and 59 cell lines exhibited low SMAD4 levels. Of these cell lines, 15 cell lines possessed both high SKIL expression and low SMAD4 expression. By comparative marker selection analysis (23), we identified the top 50 genes that were correlated with either high SKIL expression or low SMAD4. Among these genes, 13 were present in both lists, which is significantly higher than what is expected by chance (p<0.001 by a binomial distribution test) (Fig. 5A and Supplementary Table S5). At least 6 of the intersecting genes have been reported to be involved in regulation of invasion including TCF8 (ZEB1) (24), EHF (25), FOXQ1 (26), MARVELD3 (27), ST14 (28) and TWIST1 (29). These observations suggest that high SKIL or low SMAD4 gene expression affected signaling pathways implicated in invasion.

Figure 5. SKIL induces SLUG, which is required for SKIL-induced invasion.

(A) A Venn diagram showing the top 50 genes correlating with either high SKIL expression or low SKIL expression and the significant intersect between these two lists (p<0.001, binomial distribution test). The overlapping genes are listed below the diagram. (B) SLUG is required for SKIL induced Matrigel invasion. Suppression of SLUG significantly reduced SKIL induced invasion (p=0.03, student’s t-test). Bars indicate average number of invaded cell. (C) Suppression of SLUG in SKIL overexpressing cells had no effect on proliferation. Graph shows cell doublings over indicated amount of time. An shRNA targeting GFP was used as negative control. (D) SKIL overexpression induced SLUG expression. (E) SKIL overexpression increased gene expression of invasion and EMT related genes of which a subset could be reversed by SLUG suppression, marked as SLUG-dependent. mRNA levels were determined by quantitative real time PCR. (F) SLUG overexpression increased gene expression of the same set of genes, which were determined to be SLUG dependent in panel E. (G) Suppression of SMAD4 significantly induced Matrigel invasion (p=0.02, student’s t-test). Suppression of SLUG reversed the invasion induced by suppression of SMAD4 (p=0.05, student’s t-test). The bars represent average number of invaded cells. The experiments in this figure were performed in HMLE-MEKDD cells except panel A. Error bars = 1 S.D.

Since we found an overlap between the expression of genes related to invasion and EMT in cells having high SKIL or low SMAD4 expression, we tested the whether the role of EMT master regulators in invasion. TWIST1, SNAIL (SNAI1) and SLUG (SNAI2) are well-established transcriptional regulators of invasion and epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) (30) and have been reported to be components of the TGF-beta signaling pathway (31). To test if invasion induced by expression of SKIL was dependent on the expression of any of these genes, we suppressed the expression of these genes using specific shRNAs in SKIL-expressing HMLE-MEKDD cells. We found that suppression of SLUG significantly inhibited invasion (p=0.03) (Fig. 5B) but did not affect cell proliferation (Fig. 5C). We also found that SLUG protein levels were up regulated in SKIL expressing cells (Fig. 5D). To investigate if SLUG had any effect on SKIL-induced gene expression, we investigated how SLUG suppression affected a set of TGF-beta and invasion related genes. We found that several genes were up regulated by SKIL and reversed upon SLUG suppression, including SNAIL, TWIST1, PLAUR and VIM (Fig. 5E). Furthermore, upon overexpression of SLUG the same subset of genes was up regulated (Fig. 5F).

Since SKIL has been suggested to inhibit SMAD4 function, we tested the effect on suppression of SMAD4 in our system. We found that suppression of SMAD4 induced invasion and that suppression of SLUG significantly reversed this phenotype (p=0.02 and p=0.05; Fig. 5G). These observations implicate SKIL as a regulator of SMAD4-mediated invasion, which required SLUG.

TLOC1 and SKIL cooperate to induce transformation

Since TLOC1 and SKIL frequently are co-amplified, we investigated if manipulating the expression of these genes cooperated to induce cell transformation. We found that overexpression of TLOC1 and SKIL together induced a significant increase in anchorage independent growth (p=0.003; Fig. 6A), which failed to be explained by a general increase in cell proliferation (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6. TLOC1 and SKIL cooperate to induce anchorage independent growth.

(A) HMLE-MEKDD expressing different combinations of genes were tested for anchorage independent growth. The bars illustrate average number of colonies. A significant difference was detected between TLOC1 and control as illustrated in the graph (p=0.003, student’s t-test), and between was potentiated in combination with SKIL. (B) Growth rate of cells used in panel A showed no significant differences in growth rate. Cells were cultured, counted and reseeded at indicated time points and the cumulative increase in cell number is shown. (C) TLOC1 or SKIL display no combinatorial effect in anchorage independent growth with PIK3CA or SOX2. Bars display average colony number. Error bars = 1 S.D.

Having investigated cooperative effects of SKIL and TLOC1, we tested the effects of co-expressing TLOC1 and SKIL with PIK3CA or SOX2 from neighboring amplification peaks. We found that both PIK3CA and SOX2 overexpression induced anchorage independent growth in HMLE-MEKDD cells but exhibited no cooperative effect with TLOC1 or SKIL (Fig. 6C). These observations suggest that TLOC1 and SKIL induce transformation independently of PIK3CA or SOX2.

Discussion

3q26 is amplified in several of cancer types including lung, ovarian and breast and is correlated with poor prognosis and an invasive phenotype (32). Here we have systematically interrogated the function of the genes harbored in the minimal common amplified region by suppressing or overexpressing each of these in human cancer cell lines. We found that TLOC1 expression induced anchorage independent growth, while SKIL induced invasion and both of these genes induced tumor formation. Co-expression of TLOC1 and SKIL induced cooperative cell transformation. Together these observations identify TLOC1 and SKIL as transforming genes resident in 3q26 and provide additional evidence that recurrently amplified regions may harbor more than one gene involved in malignant transformation (33). Although we have identified TLOC1 and SKIL as two genes resident in the minimal common amplified region at 3q26 that contribute to cell transformation, other genes in this region may contribute to other cancer-related phenotypes.

Prior work has implicated TLOC1 to be a component of the translocon complex, which is an important component in protein translation. Here we found that TLOC1 interacts with a number of proteins involved in translation including DDX3X, whose expression was required for TLOC1-induced transformation. The interaction of TLOC1 and DDX3X requires the amino terminal end of TLOC1, a region previously implicated for its interaction with ribosomes (13). DDX3X has been reported to be part of a complex including PABPC1 (PABP), which we also identified as a TLOC1 binding partner. This complex was shown to promote translation of a selected set of mRNAs (34). Taken together, these observations suggest that TLOC1 and DDX3X are components of a macromolecular complex involved in translational regulation.

Several lines of evidence now implicate translation as a key process perturbed in cancer cells (35). For example, MYC induced transformation has been shown to perturb the shift between cap- to IRES-dependent translation during the cell cycle and lead to genomic instability (36). The finding that TLOC1 and DDX3X induced transformation through inhibition of IRES-dependent translation is consistent with this model. We note that mutations involving DDX3X have recently been described in several cancer types including head and neck cancer (37).

It remains unclear whether perturbation of translation contributes to transformation through specific transcripts or global dysregulation of translation. Several recent reports suggest that subsets of mRNAs are specifically regulated. For example, oncogenic mTOR signaling has been shown to control the translation of a set of pro-invasive transcripts in prostate cancer (38), and has been also reported to control translation of TOP-motif containing mRNAs (39). These observations suggest that perturbation of translation control likely affects specific transcripts that contribute to transformation.

We found that TLOC1 overexpression decreased EIF4BP1 phosphorylation, which is predicted to induce decreased translation. Overexpression of EIF4G also induces tumorigenic growth of NIH3T3 cell (40), and an inhibitor targeting EIF4G, 4EGI-1, was shown to inhibit growth of human breast and melanoma cancer xenografts (41). The finding that TLOC1 is not only amplified in a significant fraction of cancers but also contributes directly to cell transformation suggests dysregulation of protein translation by perturbation of TLOC1 or DDX3X contributes to tumorigenicity.

We identified a shorter splice variant of TLOC1 that also had transforming capacity, an inhibitory effect on translation and associated with DDX3X. Since this form lacks the two trans-membrane domains of TLOC1, we predicted that this form does not bind to the ER. However, despite these differences, we found that both isoforms induced cell transformation. Two mRNA forms of the TLOC1 ortholog in Drosophila melanogaster, Trp1, have been shown to be selectively expressed: a 1.6 kb form, which is expressed in the male reproductive system, and a 2.2 kb form confined to other tissues (42). The difference between the 2.2 and 1.6 kb transcripts is close to the difference of the 537 bases of the two TLOC1 forms. These observations suggest that these two isoforms may have tissue specific effects but that both are transforming when inappropriately expressed.

We also identified SKIL in 3q26 as an inducer of invasion. SKIL has been reported to inhibit SMAD4 function by repressing its transcriptional activity by recruitment of the transcriptional co-repressor N-CoR (21). Although SKIL protein levels did not strictly correlate with copy number, we showed that both overexpression of SKIL or suppression of SMAD4 induced an invasive phenotype through up-regulation of SLUG, thus illustrating two common genomic events in cancer that lead to inactivation of the TGF-beta pathway and subsequently induction of an invasive phenotype.

PIK3CA and SOX2 are other oncogenes that also reside on the 3q arm and are often co-amplified with 3q26. To investigate if TLOC1 or SKIL acted in a cooperative manner with PIK3CA or SOX2, we expressed combinations of genes but did not observe any cooperation between PIK3CA or SOX2 and TLOC1 and SKIL. These observations suggest that PIK3CA or SOX2 act independently of TLOC1 and SKIL; however, we note that our experiments do not eliminate the possibility that these genes cooperate in other assays in vivo. Moreover, we confirmed that PIK3CA mutations occur at equal frequency in cells that harbor or lack increased copy number at 3q26.

We found that TLOC1 and SKIL cooperated to induce anchorage independent growth. Cooperating cancer drivers in amplification peaks have previously been described. YAP1 and BIRC2 (cIAP1), which reside in the same amplicon in liver cancer, have been shown to have a cooperative effect on tumorigenesis (43). In addition, EGFR is frequently co-amplified with the neighboring gene SEC61G in glioma, and both have been shown to be required for tumor cell survival (44). Of note, SEC61G and TLOC1 interact in the translocation channel. In a similar manner, 8p22 has been reported to include a cluster of cooperating tumor suppressors (33). Although we showed that overexpression of TLOC1 affects protein translation and anchorage independent growth and SKIL affects cell invasion, it remains unclear whether these functions cooperate or act in parallel in vivo.

Moreover, further studies are necessary to determine whether targeting these pathways will lead to clinical responses. Indeed, an inhibitor of EIF4G, 4EGI-1, has been shown to inhibit growth of human breast and melanoma cancer xenografts (41). In addition, inhibitors of DDX3X, which has also been reported to be important for HIV propagation, have been developed (45). Further work will be necessary to determine whether 3q26 amplification predicts the response of cancer cells to these inhibitors.

In aggregate, these studies extend work suggesting that regions of recurrent SCNAs may harbor more than one driver gene that participate in different aspects of tumor initiation or progression. Future efforts to interrogate such regions will not only require systematic interrogation of resident genes but also the use of multiple assays to assess potentially complementary phenotypes.

Materials and methods

Copy number analysis

GISTIC profiles were created from Tumorscape with 3131 tumor samples as previously described (1, 6). To create amplification diagrams of tumor samples and the screened cell lines, copy number illustrations were made with the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) (46). The TCGA was also queried for amplification of genes in the minimal amplified region of 3q26 (2, 7).

Cell culture, vectors and lentiviruses

HMLE cells expressing hTERT and SV40 Early Region have been described (47). To express or suppression genes retroviral and lentiviral vectors were used (pBabe, pWzl, pLex, pLKO) as described (48, 49). pBabe-Puro-Flag-DEST, pLEX-Puro-V5-DEST and pWzl-Neo-Flag-DEST constructs were generated by Gateway cloning from pDONR223 constructs acquired from either the Human ORFEOME (50) or from BP cloning reactions of BP tagged PCR products. Truncation mutants of TLOC1 were created by PCR amplification with BP tagged primers (Supplementary Table S6) and BP ligation (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), into pDONR223 and subsequent LR ligation (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) into a viral destination vector. The identity of the cell lines used in this study were verified by the CCLE.

RNAi experiments

ShRNAs were obtained from the RNAi Consortium (TRC). The corresponding shRNAs are listed in Supplementary Table S7. 10 different Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP)-specific shRNAs were used as unrelated negative controls. Lentiviral infections were performed as described (49). The suppression of each shRNA was determined in a parallel experiment where MCF7 cell were infected, selected and cultured in a similar fashion as in the screen. The shRNA suppression efficiency was determined by quantitative real time PCR. Primers are listed in Supplementary Table S8. The effects of suppressing genes resident in 3q26 were calculated by RIGER (RNAi Gene Enrichment Ranking) (8). RIGER is a method similar to GSEA (Gene Set Enrichment Analysis) (51) to summarize the effects of multiple shRNAs into a single per-gene score. First, we weighted each shRNA by its target suppression efficiency and computed a differential proliferation score (blue lines in Fig. 2A) for each shRNA according to the difference of mean proliferation between the cells harboring 3q26 and controls. These scores were sorted from high to low and each gene was assigned an “enrichment” score (red lines in Fig. 2A) according to how over-represented their shRNAs were in the sorted list using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov weighted statistic. The positive (negative) enrichment scores are normalized using the absolute value of the mean of the positive (negative) values in a permutation-based null distribution. This null distribution was also used to generate nominal p-values and False Discovery Rates (FDR) (see Fig. 2A). The false discovery rate is the expected proportion of false positives among all queries.

Anchorage independent colony growth

HMLE cells expressing the different genes were assayed for their colony formation capacity as described (9). In addition to the 20 genes, we included myristoylated AKT1 (myr-AKT1), which has been shown to collaborate with MEKDD and transform immortalized breast epithelial cells, as a positive control. As negative controls, we used corresponding vectors expressing YFP (Yellow Fluorescent Protein), hcRED (Heteractis crispa Red), LacZ (β-galactosidase) or LUC (Luciferase). To test the function of TLOC1 associated proteins, each candidate was targeted with two shRNAs in TLOC1 overexpressing HMLE-MEKDD cells.

Invasion experiments

Invasion capacity of cells was determined by plating 50,000 cells in the upper chamber of Matrigel (BD Biosciences, Clontech, Bedford, MA, USA) coated trans-well invasion chambers according to manufacturer’s instructions. The cells were seeded in media containing no growth factors, and media with normal amount of growth factors was added to the lower chamber. An shRNA targeting CDH1 (E-cadherin) (29) or overexpression of YFP served as positive or negative control, respectively. Invasion was determined after 24–48 hours by staining with Ginsa or Hoechts and counting the number of invaded cells with ImageJ (Rasband, W.S., ImageJ, U. S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA, http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

Quantitative real time PCR

RNA was harvested using RNeasy (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Complementary DNA was prepared using Advantage RT-for-PCR (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA). Quantitative PCR was carried out using SYBR (Applied Biosystems, Beverly, MA, USA). Primers are listed in Supplementary Table 8. For the gene suppression experiments (Supplementary Figure S1), MCF7 cells propagated in 24-well tissue culture plates were infected with individual shRNAs at a MOI < 1 (Multiplicity Of Infection). After infection, the cells were selected with puromycin and passaged to eliminate dead cells. RNA was purified with RNeasy (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA) and converted into cDNA by reverse transcription using Superscript II (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA). Gene expression levels for each targeted gene and GAPDH were determined for each shRNA infected sample by real time PCR in a 7300 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA). The relative expression level per gene was normalized against GAPDH levels and compared to a reference sample where GFP had been targeted as an unrelated shRNA control. Expression was determined by single measurements from three different biological replicates.

For genomic quantitative real time PCR analysis DNA was purified from cells with QIAamp (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA). Genomic levels were determined by real time PCR in a 7300 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) with primers specific for 3q26 (Supplementary Table S8). Primers specific for genomic LINE-1 were used to normalize for genomic input (Supplementary Table S8).

Immunoblotting

For immunoblot analyses, samples were harvested in 1% NP-40 or RIPA supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose filters with the iBlot system (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Bedford, MA, USA). Antibodies used were anti-Flag M2 (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA), anti-V5 (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Bedford, MA, USA), TLOC1 (SEC62, #HPA014059) and DDX3X (#HPA001648, Prestige Antibodies, Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA), SNON (SKIL) (#4973), SLUG (#9589), EIF4G (#2469), EIF4E (#9742), EIF4EBP1 (#9644), pEIF4EBP1(Thr37/45) (#9459), pEIF4EBP1(Ser65) (#9456), (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA, USA), SNON (SKIL) (H317, sc-9141, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA).

Proliferation experiments

HMLE-MEKDD cells expressing vector control or gene of interest or cancer cell lines expressing shRNA against control or gene of interest were plated in six-well plates. Cells were counted after indicated time and re-plated at the same amounts and this cycle was repeated as indicated. Increase in cell number was calculated and plotted as accumulated increase in cell number.

TLOC1 association experiments

100 mg protein lysates were generated from HMLE-MEKDD cell expressing V5-tagged LUC or TLOC1 by lysis in 1% NP-40 supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Immune complexes were precipitated over night with anti-V5-beads (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). A fraction of the precipitated product was analyzed on PAGE for silver staining and immunoblotting to confirm that V5-tagged TLOC1 was isolated. The rest of the protein was separated on gels, stained by SYPRO Ruby protein gel stain and lanes were isolated. The IgG bands were removed from the lanes and the rest was submitted for mass spectrometry analysis.

Excised gel bands were subjected to in-gel trypsin digestion. Gel pieces were washed and dehydrated with acetonitrile and rehydrated in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate containing 12.5 ng/µl modified sequencing-grade trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI) at 4°C. After 45 min, trypsin solution was removed and replaced with 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate solution and incubated at 37°C for 16 hours. Peptide containing ammonium bicarbonate extract was removed and remaining peptides were eluted with 50% acetonitrile containing 1% formic acid and dried in a speed-vac.

Samples were reconstituted in 2.5% acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid and separated over a nano-scale reverse-phase HPLC capillary packed with C18 spherical silica beads (52). Sample was loaded in an equilibrated Famos auto sampler (LC Packings, San Francisco CA). A gradient was formed and peptides were eluted with increasing concentrations of solvent (97.5% acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid).

Eluted peptides were subjected to electrospray ionization and entered into an LTQ Velos ion-trap mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher, San Jose, CA). Peptides were detected, isolated, and fragmented to produce a tandem mass spectrum of specific fragment ions for each peptide. Peptide sequences were determined by matching protein databases with the acquired fragmentation pattern by Sequest (ThermoFisher, San Jose, CA) (53).

Translation measurements

Cap- and IRES-dependent translation was determined by transient transfection of the bi-cistronic translation reporter into HMLE-MEKDD cells stably expressing BFP (Blue Fluorescent Protein) as unrelated control or TLOC1. Cells were plated in 96-well cell assay plates at 100,000 cells per well, transfected with pDL/N and incubated for 48 hours. Renilla and Firefly luciferase activity was determined with Dual-Glo Luciferase Assay system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA).

Cap-binding assay

Cap-associated proteins were precipitated with 7-metylated GTP beads from cell lysates derived from TLOC1 or BFP overexpressing cells. 7-methylated GTP sepharose beads (GE Healthcare Life Science, Waukesha, WI, USA) were used according to manufacturers instructions to precipitate cap-complexes.

Gene expression analysis

For the gene expression analysis between cell lines with or without 3q26 amplification, gene expression and copy number data was downloaded from CCLE for 967 cancer cell lines (54). Cell lines with a log2 amplification value higher than 0.3 at SKIL were defined as 3q26 amplified and the rest as normal 3q. A comparative marker selection based on a two-sided T-test was performed between the two classes based on their gene expression in GenePattern (55).

Tumor formation assays

Tumor xenograft experiments were performed as described (9). Tumor formation was assessed 8 wks after injection. Tumors were scored when they reached 5 mm3.

Supplementary Material

Statement of significance.

These studies identify TLOC1 and SKIL as driver genes in 3q26. These observations provide evidence that regions of somatic copy number gain may harbor cooperating genes of different but complementary functions.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: This work was supported in part by NIH/NCI grants R01 CA130988 (WCH), RC2 CA148268 (WCH), U54 CA112962 (WCH) and the Sweden-America Foundation (DH), Ernst O. Ek fund (DH).

We thank members of the Hahn and Cichowski labs for helpful discussions. We also thank P. Hammerman, M. Pop, H. Widlund, for useful input. We thank R. Tomaino at the Taplin Mass Spectrometry facility for performing the mass spectrometry experiments.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: In compliance with Harvard Medical School guidelines, we disclose that L.A.G., R.B. and W.C.H. are consultants for Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

References

- 1.Beroukhim R, Mermel CH, Porter D, Wei G, Raychaudhuri S, Donovan J, et al. The landscape of somatic copy-number alteration across human cancers. Nature. 2010;463:899–905. doi: 10.1038/nature08822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.TCGA. Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature. 2008;455:1061–1068. doi: 10.1038/nature07385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woenckhaus J, Steger K, Werner E, Fenic I, Gamerdinger U, Dreyer T, et al. Genomic gain of PIK3CA and increased expression of p110alpha are associated with progression of dysplasia into invasive squamous cell carcinoma. J Pathol. 2002;198:335–342. doi: 10.1002/path.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bass AJ, Watanabe H, Mermel CH, Yu S, Perner S, Verhaak RG, et al. SOX2 is an amplified lineage-survival oncogene in lung and esophageal squamous cell carcinomas. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1238–1242. doi: 10.1038/ng.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Massion PP, Taflan PM, Jamshedur Rahman SM, Yildiz P, Shyr Y, Edgerton ME, et al. Significance of p63 amplification and overexpression in lung cancer development and prognosis. Cancer Res. 2003;63:7113–7121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tumorscape - Broad Institute. [cited 2012 Dec 22]; Available from: http://www.broadinstitute.org/tumorscape.

- 7.BioPortal for Cancer Genomics. [cited 2012 March 22]; Available from: http://www.cbioportal.org/public-portal/.

- 8.Luo B, Cheung HW, Subramanian A, Sharifnia T, Okamoto M, Yang X, et al. Highly parallel identification of essential genes in cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:20380–20385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810485105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boehm JS, Zhao JJ, Yao J, Kim SY, Firestein R, Dunn IF, et al. Integrative genomic approaches identify IKBKE as a breast cancer oncogene. Cell. 2007;129:1065–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barretina J, Caponigro G, Stransky N, Venkatesan K, Margolin AA, Kim S, et al. The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature. 2012;483:603–607. doi: 10.1038/nature11003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rothblatt JA, Deshaies RJ, Sanders SL, Daum G, Schekman R. Multiple genes are required for proper insertion of secretory proteins into the endoplasmic reticulum in yeast. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:2641–2652. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.6.2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilkinson BM, Regnacq M, Stirling CJ. Protein translocation across the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum. J Membr Biol. 1997;155:189–197. doi: 10.1007/s002329900171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muller L, de Escauriaza MD, Lajoie P, Theis M, Jung M, Muller A, et al. Evolutionary gain of function for the ER membrane protein Sec62 from yeast to humans. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:691–703. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-08-0730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Panzner S, Dreier L, Hartmann E, Kostka S, Rapoport TA. Posttranslational protein transport in yeast reconstituted with a purified complex of Sec proteins and Kar2p. Cell. 1995;81:561–570. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yao L, Yan X, Dong H, Nelson DR, Liu C, Li X. Expression of an IRF-3 fusion protein and mouse estrogen receptor, inhibits hepatitis C viral replication in RIG-I-deficient Huh 7.5 cells. Virol J. 2011;8:445. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asano K, Kinzy TG, Merrick WC, Hershey JW. Conservation and diversity of eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF3. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1101–1109. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shih JW, Tsai TY, Chao CH, Wu Lee YH. Candidate tumor suppressor DDX3 RNA helicase specifically represses cap-dependent translation by acting as an eIF4E inhibitory protein. Oncogene. 2008;27:700–714. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hosoda N, Lejeune F, Maquat LE. Evidence that poly(A) binding protein C1 binds nuclear pre-mRNA poly(A) tails. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:3085–3097. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.8.3085-3097.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Venkatesan A, Sharma R, Dasgupta A. Cell cycle regulation of hepatitis C and encephalomyocarditis virus internal ribosome entry site-mediated translation in human embryonic kidney 293 cells. Virus Res. 2003;94:85–95. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(03)00136-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gingras AC, Gygi SP, Raught B, Polakiewicz RD, Abraham RT, c MF, et al. Regulation of 4E-BP1 phosphorylation: a novel two-step mechanism. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1422–1437. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.11.1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stroschein SL, Wang W, Zhou S, Zhou Q, Luo K. Negative feedback regulation of TGF-beta signaling by the SnoN oncoprotein. Science. 1999;286:771–774. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5440.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Wilentz RE, Argani P, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Kern SE, et al. Dpc4 protein in mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: frequent loss of expression in invasive carcinomas suggests a role in genetic progression. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1544–1548. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200011000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gould J, Getz G, Monti S, Reich M, Mesirov JP. Comparative gene marker selection suite. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1924–1925. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peinado H, Olmeda D, Cano A Snail. Zeb and bHLH factors in tumour progression: an alliance against the epithelial phenotype? Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:415–428. doi: 10.1038/nrc2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Albino D, Longoni N, Curti L, Mello-Grand M, Pinton S, Civenni G, et al. ESE3/EHF Controls Epithelial Cell Differentiation and Its Loss Leads to Prostate Tumors with Mesenchymal and Stem-like Features. Cancer Res. 2012 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang H, Meng F, Liu G, Zhang B, Zhu J, Wu F, et al. Forkhead transcription factor foxq1 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1292–1301. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kojima T, Takasawa A, Kyuno D, Ito T, Yamaguchi H, Hirata K, et al. Downregulation of tight junction-associated MARVEL protein marvelD3 during epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human pancreatic cancer cells. Exp Cell Res. 2011;317:2288–2298. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2011.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng H, Fukushima T, Takahashi N, Tanaka H, Kataoka H. Hepatocyte growth factor activator inhibitor type 1 regulates epithelial to mesenchymal transition through membrane-bound serine proteinases. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1828–1835. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang J, Mani SA, Donaher JL, Ramaswamy S, Itzykson RA, Come C, et al. Twist, a master regulator of morphogenesis, plays an essential role in tumor metastasis. Cell. 2004;117:927–939. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taube JH, Herschkowitz JI, Komurov K, Zhou AY, Gupta S, Yang J, et al. Core epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition interactome gene-expression signature is associated with claudin-low and metaplastic breast cancer subtypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:15449–15454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004900107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nieto MA. The snail superfamily of zinc-finger transcription factors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:155–166. doi: 10.1038/nrm757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akagi I, Miyashita M, Makino H, Nomura T, Hagiwara N, Takahashi K, et al. SnoN overexpression is predictive of poor survival in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2965–2975. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9986-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xue W, Kitzing T, Roessler S, Zuber J, Krasnitz A, Schultz N, et al. A cluster of cooperating tumor-suppressor gene candidates in chromosomal deletions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:8212–8217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206062109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soto-Rifo R, Rubilar PS, Limousin T, de Breyne S, Decimo D, Ohlmann T. DEAD-box protein DDX3 associates with eIF4F to promote translation of selected mRNAs. EMBO J. 2012;31:3745–3756. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silvera D, Formenti SC, Schneider RJ. Translational control in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:254–266. doi: 10.1038/nrc2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barna M, Pusic A, Zollo O, Costa M, Kondrashov N, Rego E, et al. Suppression of Myc oncogenic activity by ribosomal protein haploinsufficiency. Nature. 2008;456:971–975. doi: 10.1038/nature07449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stransky N, Egloff AM, Tward AD, Kostic AD, Cibulskis K, Sivachenko A, et al. The mutational landscape of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Science. 2011;333:1157–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.1208130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hsieh AC, Liu Y, Edlind MP, Ingolia NT, Janes MR, Sher A, et al. The translational landscape of mTOR signalling steers cancer initiation and metastasis. Nature. 2012;485:55–61. doi: 10.1038/nature10912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thoreen CC, Chantranupong L, Keys HR, Wang T, Gray NS, Sabatini DM. A unifying model for mTORC1-mediated regulation of mRNA translation. Nature. 2012;485:109–113. doi: 10.1038/nature11083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fukuchi-Shimogori T, Ishii I, Kashiwagi K, Mashiba H, Ekimoto H, Igarashi K. Malignant transformation by overproduction of translation initiation factor eIF4G. Cancer Res. 1997;57:5041–5044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen L, Aktas BH, Wang Y, He X, Sahoo R, Zhang N, et al. Tumor suppression by small molecule inhibitors of translation initiation. Oncotarget. 2012;3:869–881. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Noel P, Cartwright IL. A Sec62p-related component of the secretory protein translocon from Drosophila displays developmentally complex behavior. EMBO J. 1994;13:5253–5261. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06859.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zender L, Spector MS, Xue W, Flemming P, Cordon-Cardo C, Silke J, et al. Identification and validation of oncogenes in liver cancer using an integrative oncogenomic approach. Cell. 2006;125:1253–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lu Z, Zhou L, Killela P, Rasheed AB, Di C, Poe WE, et al. Glioblastoma proto-oncogene SEC61gamma is required for tumor cell survival and response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cancer Res. 2009;69:9105–9111. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Radi M, Falchi F, Garbelli A, Samuele A, Bernardo V, Paolucci S, et al. Discovery of the first small molecule inhibitor of human DDX3 specifically designed to target the RNA binding site: towards the next generation HIV-1 inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:2094–2098. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.12.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdottir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:24–26. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Elenbaas B, Spirio L, Koerner F, Fleming MD, Zimonjic DB, Donaher JL, et al. Human breast cancer cells generated by oncogenic transformation of primary mammary epithelial cells. Genes Dev. 2001;15:50–65. doi: 10.1101/gad.828901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morgenstern JP, Land H. Advanced mammalian gene transfer: high titre retroviral vectors with multiple drug selection markers and a complementary helper-free packaging cell line. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:3587–3596. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.12.3587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moffat J, Grueneberg DA, Yang X, Kim SY, Kloepfer AM, Hinkle G, et al. A lentiviral RNAi library for human and mouse genes applied to an arrayed viral high-content screen. Cell. 2006;124:1283–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.The CCSB Human Orfeome Collection. [cited 2012 Dec 22]; Available from: http://horfdb.dfci.harvard.edu.

- 51.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peng J, Gygi SP. Proteomics: the move to mixtures. J Mass Spectrom. 2001;36:1083–1091. doi: 10.1002/jms.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yates JR, 3rd, Eng JK, McCormack AL, Schieltz D. Method to correlate tandem mass spectra of modified peptides to amino acid sequences in the protein database. Anal Chem. 1995;67:1426–1436. doi: 10.1021/ac00104a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Broad-Novartis Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) [cited 2012 Dec 22]; Available from: www.broadinstitute.org/ccle/home.

- 55.GenePattern. [cited 2012 Dec 22]; Available from: http://genepattern.broadinstitute.org.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.