In 2011, nearly 1.65 million Americans were enrolled in a hospice program, representing nearly 45% of all deaths (1). With a focus on comfort care and quality of life for those diagnosed with a terminal illness, hospice has been considered the gold standard of care for those facing the end of life. In the United States, this specialized medical care is based upon a philosophy that involves controlling pain, treating the patient and family as a unit of care, and providing services from an interdisciplinary team. Almost 90% of these services are paid for under the Medicare and Medicaid programs. Medicare Conditions of Participation require hospice teams to meet at least every two weeks to review goals of care for every hospice patient. These meetings, referred to as interdisciplinary team (IDT) or interdisciplinary group (IDG) meetings, are required to have at least a physician, nurse, social worker, and counselor (2) present to review plans of care. These meetings often contain additional staff, and several patients are reviewed in one session. These meetings last between one and three hours (3), with an average of 3.5 minutes spent discussing each patient (4).

The traditional roots of hospice have included the philosophy that the patient/family owns the plan of care. Their participation in the care team’s decision-making process is a basic tenet of the hospice movement. According to Saltz and Schaefer (5) including patients and families as members of the healthcare team has numerous beneficial outcomes. In hospice, the IDT meeting is a viable site that allows patient/family access to the hospice team, which opens the door for improved assessment, care planning, and implementation (6). Many researchers have written about the importance of involving patients and family members in IDT activities (5, 7–11) and theorized that such inclusion will improve satisfaction, coordination of care (12), communication, and access to specialists (11, 13).

However, numerous barriers prevent the majority of hospice patients/families from participating in IDT meetings (14) in which they could represent their experiences, values, and concerns. Barriers include the physical limitations that prevent patients from traveling and require informal caregivers to remain at home to attend to patients’ physical and psychosocial needs. Team meetings take place at a hospice office. Patients and family members serving as informal caregivers, especially those in rural areas, would have to travel significant distances to participate in person. Even if they were able to attend, hospice staff typically spends only a few minutes on any single patient, which would make a long journey an inefficient use of time for patients and informal caregivers. In effect, hospice patients and informal caregivers do not routinely participate in the discussions that develop the plan of care that they should theoretically control (14).

ACTIVE (Assessing Caregivers for Team Intervention via Video Encounters) is a randomized controlled trial currently underway to address this issue. The project uses web-conferencing to bridge geographic barriers and empower hospice informal caregivers and patients (when able) to be in their home while joining an interdisciplinary team meeting. This research project, funded by the National Institute on Nursing Research (R01NR012213), has successfully used this intervention with over 350 caregivers since its implementation in October 2010.

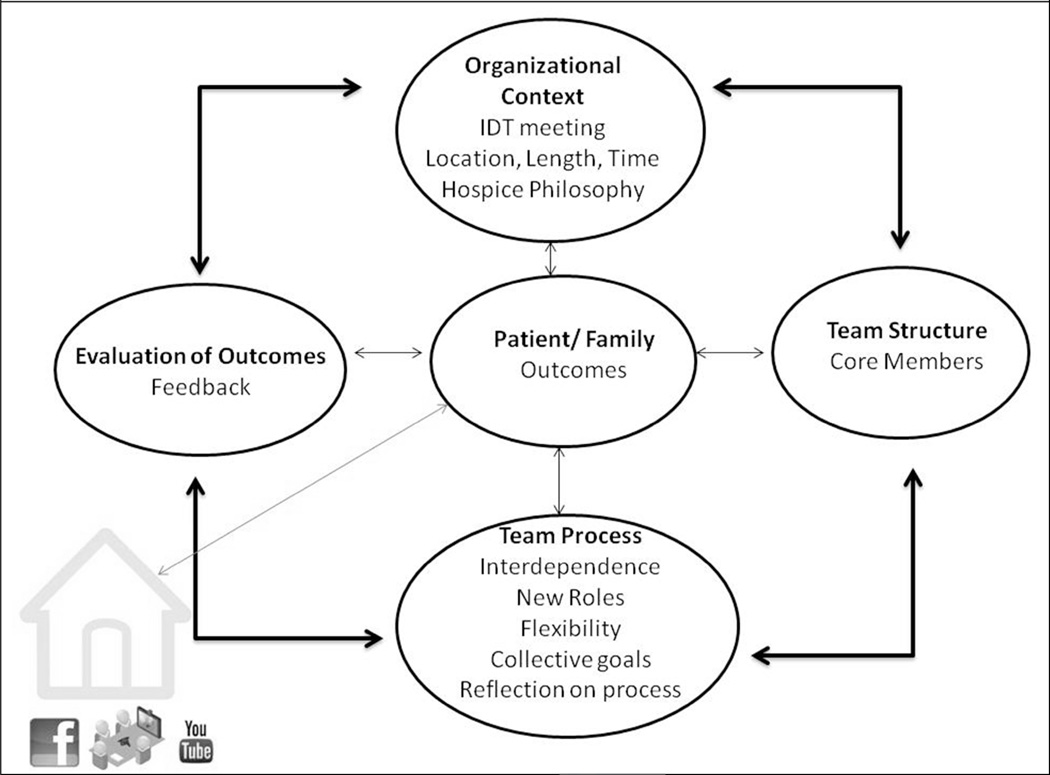

The theoretical model for ACTIVE is modified from Saltz and Schaefer (5) and outlines the value of the organizational context that supports family involvement, the role of the family member as either a lay person or specialist, the process of teamwork that emerges, as well as the feedback and outcomes that emerge from participation not only for the team but also for the individual. Saltz and Schaefer (5) identify four components of an IDT model inclusive of family: context, structure, process, and outcomes. The organizational context influences team structure, which in turn impacts team processes, ultimately determining how teams evaluate outcomes. Saltz and Schaefer maintain that, when family input into problem-solving or decision-making is lacking, care plans suffer due to incorrect assumptions about the patient/family perspectives. Finally, families influence team outcomes by providing feedback about the team as a whole (5). As a result of this collaborative process, the patient and family experience positive clinical outcomes.

The purpose of this study was to assess the experiences of informal caregivers participating in their team’s hospice interdisciplinary team (IDT) meetings. The research questions guiding this analysis are: 1) How do informal caregivers describe their experiences of participating in the hospice team meetings? 2) How do informal caregivers describe their challenges of participating in hospice team meetings?

Methods

Intervention

Detailed protocols and procedures for the ACTIVE intervention and the clinical trial examining its effectiveness, are published elsewhere (15). In summary, informal caregivers are randomized into a usual care group or an intervention group (ACTIVE). Those in the intervention group are given a web camera and taught how to use a video-conferencing website through virtual interactive families (www.vifamilies.com) so they can join in the team meeting. They are informed of the day and time their case will be discussed and asked to log into the system at a specified time. Individuals without Internet access are encouraged to connect through the teleconference website. The website allows the research staff to place individuals into a virtual “waiting room” if the team is not yet ready to discuss the case when the caregiver logs onto the website. The image of the caregiver is shown on a screen in the team meeting, allowing the team members to see the caregiver as well as the image the caregiver has of the team.

Data Collection

Research staff phoned caregivers approximately 14–21 days after the death of the hospice patient to ask them questions regarding their experiences with the intervention. The interviews took approximately 20 minutes and were conducted using a semi-structured interview guide (see Table 1). Responses were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim for analysis. The study was approved by the University of Missouri Health Sciences Institutional Review Board.

Table 1.

Follow-Up Interview Guide – Intervention Caregiver

| Follow-up interviews should be conducted between 14 and 21 days after the death or decertification of the hospice patient. The interview will be audio recorded. Each recording should begin by stating your name, the hospice site, participant number and date. |

1. How did you feel after participating in the hospice team meetings?

|

| 2. In what ways, if any, was the experience of participating in the team meetings beneficial to you? |

| 3. In what ways, if any, could the experience of participating in the team meetings have been improved? |

4. If the situation presented itself, would you like to participate again?

|

| 5. Would you recommend that other family members or caregivers of hospice patients participate in their hospice team meetings? |

6. What did you think about using the conference phone or webcam?

|

Data Analysis

Caregiver transcripts were entered into a coding website for thematic analysis (16). Two coders analyzed the transcripts using an a priori coding frame based upon our adaptation of the Saltz and Schaefer (5) theoretical model in conjunction with an initial reading of 5% of the transcripts, the themes identified in our pilot study (17), and a category of “other” used to capture emergent themes not anticipated in the coding frame. Two coders (DPO and DLA) read through 10% (n=6) of the transcripts together, applied the coding frame, and discussed the themes identified in each transcript until consensus was achieved at 80%. The remaining transcripts (n=52) were divided evenly and coded separately by each coder. After all transcripts were coded, coders met to review consistency, discuss differences, and agree on final codes. Upon review, codes were combined and clarified to create a final set of themes based on the consensus of both coders. Peer debriefing was done with all authors for consensus on the final analysis.

Results

For the larger ongoing clinical trial, we have to date randomized more than 350 caregivers, with nearly half receiving standard hospice care and the remaining half invited to participate in the team meetings related to their loved ones. The sample for the qualitative study presented here includes 56 caregivers who had completed final interviews during the first two years of the project. Table 2 summarizes the demographics of these participants.

Table 2.

Summary Caregiver Characteristics (N=56 caregivers for 54 patients)

| Characteristic | N | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 44 | 78.6 |

| Male | 12 | 21.4 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 21–50 | 8 | 14.3 |

| 51–60 | 17 | 30.4 |

| 61–70 | 22 | 39.3 |

| 71 or more | 7 | 12.5 |

| Unknown | 2 | 3.6 |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 53 | 94.6 |

| African-American | 2 | 3.6 |

| Other | 1 | 1.8 |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 3 | 5.4 |

| High school/GED | 12 | 21.4 |

| Some college/trade school | 12 | 21.4 |

| Undergraduate degree | 13 | 23.2 |

| Graduate/professional degree | 12 | 21.4 |

| Other/unknown | 4 | 7.1 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Never married | 4 | 7.1 |

| Married | 46 | 82.1 |

| Separated | 1 | 1.8 |

| Divorced | 4 | 7.1 |

| Widowed | 1 | 1.8 |

| Relationship to Patient | ||

| Spouse | 17 | 30.4 |

| Adult child | 26 | 46.4 |

| Sibling | 2 | 3.6 |

| In-law | 7 | 12.5 |

| Other relative | 4 | 7.1 |

| Caregiver Employment | ||

| Full time | 14 | 25.0 |

| Part time | 7 | 12.5 |

| Retired | 21 | 37.5 |

| Not employed | 3 | 5.4 |

| Other/unknown | 11 | 19.6 |

| Patient’s residence* | ||

| Patient’s own home | 33 | 58.9 |

| Nursing home | 23 | 41.7 |

| Caregiver resides with patient | ||

| Yes | 27 | 48.2 |

| No | 29 | 51.8 |

Frequency of residence for patients: 31 (57.4%) reside in their own home and 23 (42.6%) reside in a nursing home.

The benefits, challenges, and feedback given by informal caregivers were thematically based on the organizational context, team structure, team process, team outcomes, and patient/family outcomes in the ACTIVE theoretical model (Figure 1), using Saltz and Schafer’s framework (5). Table 3 identifies and defines prevailing themes and provides additional illustrations of caregiver comments within those themes.

Figure 1.

ACTIVE Theoretical Model for Patient/Caregiver Involvement in Hospice Teams

Table 3.

Final Themes, Definitions, and Examples of Narratives (n=56)

| Theme | Definition/Sub Theme | Examples of Narratives |

|---|---|---|

| Organizational Context | Factors which encourage or discourage patient/caregiver involvement in the team meeting. | |

| Technology facilitated involvement | And it felt like, just from doing one video conference and talking to people, it felt like I knew them better. At least I knew who they were, as opposed to just congregating around when mom was dying. 02-0108-0049 | |

| Technology hampered involvement | …you know, sometimes it would, we'd step on each other and it was hard to understand. 01-0014-0006 | |

| Time involved was positive | One, just knowing that everybody was getting together and looking at Mom as a whole was comforting to me. Knowing that there was a set process where that was done on a regular basis was reassuring…And it helped me see how very supportive. 01-0502-0139 | |

| Time involved was negative | And so I was one of their appointments but the appointments were shorter 'cause "Well, we've got to get to our next appointment." And maybe by the time they got to me, they were already running late or running behind, so it just seemed like, towards the end, everybody was more in a hurry. 02-0252-0115 | |

| Team Structure/Roles | Caregivers are viewed by the hospice staff as a lay team member with only limited knowledge, or as a specialist with tremendous knowledge as reflected by the feelings of the Caregivers. | |

| Comfortable | And I did subsequently meet some of the people who were caring for my mom. They knew who I was. I mean when I drove up to the house one day, one of the ladies who had been in the conference, one of the nurses… stopped because she recognized me from the video conference call, and knew who I was and talked to me about mom. And I had recognized her. I didn't know which one it was but I knew her face. And then I was able to--I mean I knew who Dr. [name] was and that was nice. It was nice to personally know the people that, or to have met them, everyone on the team. 02-0108-0049 | |

| Uncomfortable | I don't think there was ever anything real specific, other than kind of feeling rushed. They'd say a few things to me, and I'd say a few things back, and it was rushed. It was just rushed. 01-0302-0103 | |

| Felt involved/included | And I appreciated being involved. I think it's a-- Webinars have been around for a while. I think it's a good thing to use in patient care. 02-0104-0048 | |

| Did not feel involved | Well, we didn't get off to a good start with hospice. …It was just a bunch of people, sitting around a table at the university. I'm going, "Well, so what?” 01-0382-0120 | |

| Respected | It made me also feel like I was a part of the team. And whatever suggestions I had, they made me feel like they were well-respected and thought over before they answered to say, "We should do this or we should not do that." And I didn't get a, not a lot of "should not’s. But had I participated longer, I would have really respected, even if they had some constructive criticism. I would have respected that, and I would have done accordingly if my heart felt like this was what's best for my sister. 01-0133-0050 | |

| Disrespected | There is never a substitute for face to face….and it probably would have helped with my issues about the decision-making and kind of arbitrary authoritarian tone that that had to it. …I think it would have helped if from the beginning, there had been a face-, one face to face 01-0014-0006 | |

| Team Process | Process elements within the team influenced by family involvement | |

| Felt a part of decision making | Well, I felt like when I was making a suggestion about what would help her, I felt like it was taken into consideration. … But I also listened to the things that the doctor and the nurse was saying, which I felt like they were concerned enough to try to figure out even her medications and all of that. … So I think everything they did and said was very helpful to me. And I knew what the medicines would do as far as [patient] was concerned. But they always made sure I understand which medications did what. And that helped me a lot. 01-0133-0050 | |

| Felt left out of decision making | … I felt that they listened respectfully and they considered what I had to say. But I think in some ways, they were kind of ahead of me. 01-0305-0104 | |

| Questions answered | …I felt like with other healthcare providers, I had to track down information about my mother or track down people to be able to ask them questions. But I didn't feel that at all with [hospice name]. I just felt very supported and very--I felt like my questions and concerns were something that they weren't afraid of. 01-0069-0028 | |

| Questions left unanswered | I was definitely prompted to ask questions. But I also didn't feel like if I had a question …they were responsive to my question in the middle of the conference. 02-0303-0142 | |

| Communication facilitated involvement | …it's good to know that you have a specific time to touch base with the team. I like the team concept, not just calling and maybe talking to one person this time or one person another time. They're together and everybody's kinda hearing the same thing. So I think that's good. 02-0104-0048 | |

| Communication barriers for involvement | The nurses didn't sit down and say, "Well, this is how we're going to manage your mom's pain." They just said, "We've got it!" So what? I almost said, "So what? What do you do with it?" 02-0213-0100 | |

| Team Outcomes | Families influence team outcomes by providing feedback about the team as a whole | |

| Feedback on Patient Education | Maybe to publish--the little book that you give people about the dying process. Maybe publish the same kind of book about all the different pain killers and what they do, what they're used for, how they're prescribed, how they're administered, and what to expect. …So the hospice family members know that and know to expect that, it's easier to deal with then if the nurse comes in and says, "Well, he's in pain. We're going to give him this," and starts doing it. 02-0252-0115 | |

| Feedback on Responsiveness | I was to be able to inform the care plan team of things that my siblings and I were concerned about. So it was beneficial because I felt like that by bringing up the concern with them, it would definitely be followed up on. And I would consequently get a phone call from someone, letting me know what action or what the follow-up was with my concern. 01-0069-0028 | |

| Positive Feedback on Relationship | Most of those people had been to the house, so I knew them. But Dr. [name] in particular, I had never met him. So it was kinda nice to have a face. | |

| Negative Feedback on relationships | I just kind of ignored them and they me. So you just didn't feel like you had. I just, what I wanted to do for dad, I did. And I pretty much ignored them. 01-0382-0120 | |

| Patient/Family Outcomes | Benefits or outcomes for patients or families as a result of participation in the meetings | |

| Confidence | Just to know that I had a large number of people behind me, caring about what was going on. And it was a life-altering event for me. And I felt like--I didn't feel as alone because I had all these people that knew what was going on. That was helpful.02-0254-0116 | |

| Improved knowledge | I learned so much. If I hadn't of had those, I wouldn't have been as informed. Other than if I were, you know, if I'd have been at the nursing home at the time. You know, they took time to explain and tell us everything. But, you know, with not being at the nursing home when any of the hospice came, I felt like I would have missed out on a lot. So yeah, these, you know, the conference did keep you well informed 02-0090-0040 | |

| Other outcomes positive | But if you can find people that really care. And I'm sorry, but I read eyes. And everybody, their eyes are sincere and they really were paying attention, not only to what I asked but the family. And they were so supportive. And that's so important. It just made what I thought at first was going to be really scary-- Because I mean I knew what I could do, but then your hands get tied because you can't complete the whole thing …. And it just, when that came, it was just like, "Oh, I can breathe now." 02-0192-0091 | |

| Other outcomes negative | I think it'd be better off just to have a real working relationship with the social worker and with the people that visited there. So they knew you and you knew them, rather than do this silly thing over the phone with a microphone and a camera. And we waited until I could get on. Which is not a big deal, but it was just like, "This is just one more silly university research project thing. 01-0382-0120 | |

Organizational Context

The organizational context of the team meeting is defined as factors that encourage or discourage patient/caregiver involvement. Organizational factors found within the transcripts included comments regarding the impact of the technology as a tool for collaboration, the timing of the meetings, and the perceptions brought into the setting by either the hospice staff or the caregiver. An example of how technology facilitated the participation was identified by one caregiver who said:

I liked that because you really felt like you were in the room with you guys. That was like you were a part of it. Like you were sitting there at the table with everybody. 02-0192-0091

Similarly, an example of when the technology hampered the experience was noted by a daughter caring for her father.

The video never worked very well. We never looked at the screen like we were looking at each other. I would occasionally get a static picture, so I knew who was in the room. But it wasn't like I was actually talking to somebody.02-0252-0115

Feedback on both the timing of the team meetings (once every 14 days) as well as the time required for the meetings was also prevalent. Regarding timing, five participants were unable to participate because their loved one had died prior to their meeting, thus they were unable to benefit from participating in team meetings. Additionally, there were comments that the meetings were valuable, even if it was only one session; however, the frequency of every two weeks was mentioned as not enough. One example of this was a comment from one daughter who said:

I think maybe if they did it on maybe a weekly basis, instead of every other week, that there wouldn't be such a gap in between, and where someone could, you know, the care, or the patient themselves could have, you know, went downhill in two weeks. …A lot happens in two weeks…And so I think if they did it on a weekly basis. 02-0016-0004

The short length of the conference was expressed by some as a benefit and others as a challenge as evidenced in the comments of these two caregivers:

It made it easier for a person like me, because something like that, it would take me a couple hours to be a part of [in person] on a day that we had the meetings. To where I could [participate] in just 10 minutes, and then I was in and back out. So it's a good thing.01-0060-0024

I just felt kind of rushed. Nothing really specific, I just didn't feel satisfied…01-0302-0103

Team Structure/Roles

In understanding the impact of family participation, Saltz and Schafer (5) discuss the role of the family within the team as an important consideration. Family members can be viewed by the hospice staff as a lay team member with only limited knowledge, or as a specialist with tremendous knowledge about the patient. These roles are seen in the informal caregivers’ perceptions as they discuss their involvement and comfort with the team and respect they are shown when they participate. The overwhelming number of caregivers reported that they felt involved and comfortable participating in the team meetings and that they believed their ideas were respected. One son described his comfort with participating:

And I felt like I could talk like myself. And I know that [nurses name] knows that I'm a heavy curser. And sometimes when I knew that they were in the team meetings, I would talk like myself and nobody looked down on me 'cause I spoke the way I did.01-0298-0100

Another caregiver expressed her feelings of involvement:

Well, I think it gave me a chance to voice my opinion too, where it wasn't just like a medical situation where hospice made the calls with the doctor's permission or you know what I mean? The doctor was involved and hospice was involved. But if they also, by the meetings, I was involved. So it didn't just shut me out.02-0331-0151

Likewise, a daughter caring for her mother illustrated how her input was respected when she shared:

We were on the same page with respect to just what kind of care she would receive, in terms of her DNR. And I realized that that would be respected, that there wouldn't be any life-saving heroics or anything at that point, that she'd be allowed to die. … So I felt good about that.02-0108-0049

There were also a few caregivers who reported negative experiences as they shared that they felt uncomfortable, anxious and/or disrespected. One such example was a caregiver frustrated with feeling excluded from the team:

We never really talked long enough to--I bet we weren't on there for a minute or a couple minutes. It wasn't like a really good long conference. I felt like they just wanted to get it over with and go onto other things or talk among themselves or whatever.01-0302-0103

Similarly, another caregiver who felt the team did not value her participation, noted:

I don't think there was ever anything real specific, other than kind of feeling rushed. They'd say a few things to me, and I'd say a few things back, and it was rushed. It was just rushed.01-0302-0103

Team Process

The collaborative process within a team is changed in numerous ways with the participation of informal caregivers. The majority reported feeling they were able to participate in the decision-making regarding their loved one’s plan of care, their questions were answered, and their participation facilitated communication. Numerous examples were shared by caregivers as they described their participation in the decision-making, one such example was a daughter who shared how she felt involved with decision-making:

…we were having a problem with Dad smoking with the oxygen on. And they had brought up the safety concern to me. And I had went to my dad about it beforehand too, 'cause I'd always been trying to get him to stop smoking with his oxygen on. And they had brought it up in the meeting, and we'd come up with a couple of ideas. One of the ideas was actually implemented. Since my mom was taking care of him, with her having to take the oxygen and put it in the other room before he was able to get a cigarette. So that was kind of a group plan that we had come up with. And it seemed to work for the most part.02-0301-0140

The collaboration of family in the team meetings also gave caregivers the opportunity to ask and receive answers for their questions. There were no caregivers who said they felt they could not ask questions or that their questions were not attended to. One caregiver reported:

I found it very comforting, seeing the individuals and being able to talk to them and ask any questions, getting the feedback. That goes from social, to the religious aspect, to the doctors.01-0140-0061

The process of asking questions and shared decision-making was described as facilitating communication between the caregiver and the hospice staff. Improved communication was noted as a benefit by several caregivers, such as the one below who noted:

Well, it's good to have everybody in one place. 'Cause I would get several phone calls from other people, not at the same time, but everybody that I had talked to was at that table. 01-0183-0066

Although no one interviewed said they were unable to have their questions answered, a few caregivers did say that while participating in the meetings they did not feel involved. Still, other caregivers reported observing some communication barriers within and between the hospice staff. One caregiver explained:

But there were some of the team that to me, weren't--they didn't operate as part of the team. They were sort of independent operators. And would arrive and interject an opinion, and it wasn't--you know, it was sort of arbitrary and top-downish. And so that, I, in those cases, when that happened, and it did happen more than once, I did not feel like I was part of the decision-making process.01-0014-0006

Another caregiver shared the following example of communication confusion as the doctor and nurse interaction did not reflect the experience in the team meeting.

…sometimes, I don't think the nurse communicated everything. 'Cause when I asked about the pain med when he came out, the IV pain med, he saw no problem with that and he said that was the first he'd heard of it. I don't know if it was the first he'd heard of it or not. But when I questioned the nurse about it, she said, "That's not the first that he's heard about it.”02-0296-0138

Team Outcomes and Feedback

A major outcome of patient/caregiver participation is the feedback provided to the team and the resulting potential changes in team outcomes. Some of this feedback included the need to provide patients and informal caregivers more overall education and information, which might lead to increased involvement and satisfaction with the process. Feedback also included a need for a meaningful way for patients and informal caregivers to express praise and concern related to the responsiveness of the team and Hospice staff. Additional attention was also recommended on the benefits and challenges of informal caregiver participation and its potential affect on the caregiver-staff relationship.

When asked for feedback to the team, one caregiver shared a specific suggestion related to sharing a YouTube video and the value she found in learning what to expect in the dying process:

It's on YouTube… and it's well worth taking the hour and 35 minutes or 36 minutes and watching it because the lady explains it very very very good, very good. And I got so much out of it. That when [patient]'s time came, I could see things that had [video] told me was happening. I would suggest that you watch it, and then present it to your group and say, "Hey, maybe this is something that we could use." …But this one is just so down to earth. I mean I remember that the lady gets your attention right off the bat. 'Cause when she starts talking, she tells you her name. And she says, "I've been a hospice nurse since 1986. "And I'll tell you right now, every one of my patients have died." …it just like glues you to your chair from that point on. And then she starts talking to you and telling you. She says, "I don't talk in medical language. I just talk in plain every day language." … And tells you the different things and what to expect, what to happen, how even like she said, "You know in the movies, when you've seen when somebody dies and their eyes roll, and they go like this and their eyes are closed." She says, "It don't happen." …So I wasn't surprised when that happened. And so it's very very good. I highly recommend it to you.02-0321-0152

Similarly, several caregivers talked about appreciating the responsiveness of the staff when they needed something. One daughter-in-law shared an example of the team response:

Well, there was a time where my father-in-law had … severe intestinal cramping, and he was in a lot of pain. And I knew that when we were caring for my mother, there was a product called [drug name] which helped relieve those intense spasms. And so I asked if that would maybe be a possibility for him. And they said they'd talk to Dr. [name]. And pretty soon, the pharmacy shopped up on the doorstep with a new prescription. So yeah, I thought they responded very well.01-0578-0149

And finally, another caregiver expressed gratitude with participation in the meeting as she felt she had a relationship with staff from the meetings when her mother passed:

But the thing I thought was best about it was because I felt like I got to know and see people. And so even when we did it over the phone the few times, it was no big deal because I knew who I was talking to. And we somewhat felt that way because we'd met people in her room. But I still think the more personal vision it gives is really good. The times that it worked, I thought it worked well. Tried to keep it short on our ends because I know that there were times that they were running behind …[I would] ask more questions that day and then that's OK. They knew the answers. We were OK with that.02-0104-0048

In contrast, critical feedback was shared by two individuals who felt participation had a negative impact on relationships when the conferences were not successful. An example was shared by a caregiver who was unhappy with the hospice medical director:

I was very upset because the doctor [medical director]--first of all, he was barking at me. Which I learned later, he has a tendency to do. So that's his bedside manner, I guess. But …we were trying to get him [medical director] to take [patient] on as a primary physician so that we could bypass Dr. [primary physician] whose secretary is a ferocious gatekeeper, and she was constantly holding things up. And so [nurse] was lamenting the fact that she had to wait to get the OK. Because [name], who was the gatekeeper at Dr. [primary physician name], is really very--she just is uncooperative. …But the point was we were trying to get his OK, the doctor in the group [medical director] was insisting that [patient] had to come in and see him. …But the fact was that she was incapable of coming to see him! …Now, wait a minute now. This is hospice. This [medical director] has signed up to be at hospice, which I greatly admire. And yet everybody's come to see us and made the effort to-- I mean well, come and see her! Have you not ever heard of a house call? But he's probably busy, and I didn't make that big of a thing. …But I was upset about that.01-0305-0104

Patient/Family Outcomes

Informal caregivers also discussed personal benefits and outcomes from participating with the hospice team. Beneficial outcomes included an increase in caregiver confidence, improved knowledge, and positive relationships between the hospice staff and the caregivers or patients. One caregiver discussed her confidence:

I think it helped take burdens off of our shoulders and my shoulders. And knowing that what we were doing was right. And if we had any questions, just to, you know, ask them. And I know [nurse] has said to me that he felt we were very open and we would ask questions. He thought that was great that we would open up and ask things or tell things, how we were feeling at the time.01-0127-0045

Similarly, caregivers shared that participation had helped them learn and better understand what was happening to their loved ones such as the following caregiver who became more knowledgeable about her mother’s pain:

I was very comfortable with it, like I said. When we started out, you know, I wasn't sure, but as it went on and we were, I was reassured what I was doing was right and everything. I felt comfortable with it when I was, how I was controlling it. And knowing my mother and how we were raised, we weren't really big people on a lot of medications and stuff. So that was kind of a challenge for me to give someone, other than me, 'cause I know my own self, some pain medicine. But knowing, more knowledgeable about it and how her body was accepting it made me feel more comfortable about it. So I believe I really--I understand a lot more now.01-0127-0045

A caregiver whose loved one was in the nursing home shared the value of collaborating with hospice in the care of her mother in a nursing home as she shared:

Oh. I enjoyed being able to bring up issues that I thought someone else besides the nursing home needed to hear about. In other words, I guess it was comforting to me to be able to share a concern. Because I knew that that would give a double set of ears and eyes to look at the same issue. 01-0069-0028

Not all patient and family outcomes were experienced as positive. Negative outcomes as a result of participation included:

I think it'd be better off just to have a real working relationship with the social worker and with the people that visited there. So they knew you and you knew them, rather than do this silly thing over the phone with a microphone and a camera. And we waited until I could get on. Which is not a big deal, but it was just like, "This is just one more silly university research project thing.”01-0382-0120

Discussion

In a recent report from the PEW Foundation, caregivers in the US were found to be active users of technology, especially the Internet. Nearly 80% of caregivers were found to use the Internet to find health information as well as to find others with similar concerns as they expand their social networks (18). Similarly, hospice caregivers in our study used the web-conferencing technology to be involved in the planning of care and decision making for their loved ones, and their experiences provide feedback on ways these interactions can both benefit and be improved.

Caregivers noted two factors that encouraged or discouraged their participation in the hospice team meeting: technology and time. There were reports that the technology facilitated involvement with a visual image of the team members. From their perspective, when the connection allowed for a good visual image and quality sound, involvement was improved. However, when the audio or video was not satisfactory it presented a barrier and frustration for caregivers. Similarly, the time involved in participating for the caregivers was appreciated as they could rely on a standard time to interact with the entire team. This designated time was sometimes perceived as inadequate for caregivers if the team members made the experience feel rushed or unimportant. While satisfaction and participation were heavily dependent on the quality of the technology, both the audio and the video components, it is also noteworthy that even when communication was hampered by these difficulties, caregivers still participated and were flexible in how that happened by adjusting to use of telephone or problem-solving the technical issues. It is clear that for caregivers to feel involved with the team meeting it is critical that the team members are sensitive to the communication and caregivers do not perceive the experience as rushed or unimportant to the staff.

Caregivers’ evaluation of participation in the intervention revealed that the hospice team influences perceived outcomes. When caregivers felt comfortable interacting with the team, involved in communication, and respected for their knowledge, they reported feeling a part of the team and as a result reported benefits to the interaction. If however, the caregiver was uncomfortable with the interaction, felt uninvolved and disrespected by the team, they were less likely to value the intervention. The team can best benefit if they assist caregivers in feeling comfortable, encourage them to be involved in communication, and respect the input they provide to the discussion.

Potential strengths and weaknesses of the process of involved in collaborating with the team were noted by caregivers. Caregivers reported feeling a part of decision-making and that they had the opportunity to get questions answered. However, the process of teamwork was viewed negatively when caregivers felt left out of decision-making or when questions were left unanswered. When caregivers were encouraged to make suggestions or ask questions, communication and collaboration with the team was facilitated. On the other hand, if there was a lack of active encouragement by the staff for suggestions or solicitation of questions, caregivers felt that interaction was negative.

Following participation caregivers gave feedback on team experience and shared several suggestions for improvement of their hospice experience. Suggestions to the team included improvement in education, responsiveness, and improvements in relationships. However, if the collaborative experience was negative, caregivers reported it had a negative impact on their relationship with some hospice staff. Overall caregivers experienced beneficial outcomes from participation including improved confidence and caregiving knowledge. However, when the involvement in the meeting was not beneficial it was reported to be burdensome.

This study does not reflect the experience of all caregivers participating in hospice teams. There were caregivers who we were unable to locate following the death of their loved ones, as well as some who did not openly share much narrative about their experience. It is also interesting to note that the caregivers did not always differentiate between their hospice experience and their experiences with the study intervention. This illustrates that for many the intervention was viewed as a part of the hospice experience and not separate from it, despite signing an informed consent to participate in a research study. Research staff was clearly identified with the University when they contacted participants for follow-up data collection and these interviews, yet the research staff was often seen as a part of the hospice, and the research as a component of hospice care. The lack of differentiation is promising for the integration of ACTIVE into the day-to-day hospice care process.

Suggestions related to the timing of the team meetings and the desire for longer and more frequent interactions raise many questions. It seems apparent that team interaction every two weeks is not sufficient for caregivers, yet more frequent interaction on the part of the team would be very costly and logistically difficult. With the average total time of two hours for hospice interdisciplinary team meetings, additional collaboration time for staff is not feasible. Feedback regarding the need for additional education, more frequent interaction, and longer, less rushed interaction seem to indicate a need for some creative additional elements to the ACTIVE intervention to achieve higher impacts. Most interesting was the very positive feedback from one caregiver regarding the use of YouTube video she had found on the Internet to help her understand the dying process. This suggests that social media tools may be a viable addition to the intervention by increasing the frequency of interaction with staff and providing opportunities for additional education for all caregivers.

Conclusion

The involvement of informal caregivers in hospice care plan meetings overall was rated positively by those who participated in them. Although the role of technology in the meetings was a mixed experience and the short length of the interaction sometimes a frustration, most caregivers reported feeling a part of the team and were positive about the experience with the technology. As a result, caregivers had positive relationships with the hospice staff, felt involved in decision making, and got answers to their questions. The majority reported that the hospice staff was responsive to their needs and that participation increased their confidence in their skills, increased trust in the team, and provided a feeling of not being alone if they needed help. Besides some reported challenges with the technology, other challenges included a feeling of being rushed at times and a frustration when they did not feel included or involved when the staff did not reach out to them. Suggestions for improving the intervention included a more frequent meeting time, a need for to train hospice staff how to conduct telehealth interactions, and suggestions for additional information for caregivers.

Acknowledgements

The project described was supported by Award Number R01NR011472 (Parker-Oliver- PI) from the National Institute of Nursing Research. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Nursing Research or the National Institutes of Health. This study was also partly funded by the University of Missouri Student Research Fellowship.

Contributor Information

Debra Parker Oliver, Curtis W. and Ann H. Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Missouri; Medical Annex 306G, Columbia, Mo 65212, 573-356-6719, oliverdr@missouri.edu.

David L. Albright, School of Social Work, University of Missouri.

Robin L. Kruse, Curtis W. and Ann H. Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Missouri.

Elaine Wittenberg-Lyles, University of Kentucky, Markey Cancer Center and Department of Communication.

Karla Washington, Kent School of Social Work, University of Louisville.

George Demiris, Biobehavioral Nursing and Health Systems, School of Nursing & Biomedical and Health Informatics, School of Medicine, University of Washington.

References

- 1.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. NHPCO Facts and Figures: Hospice Care in America 2011. Alexandria, VA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Code of Federal Regulations. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office via GPO; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wittenberg-Lyles E, Parker Oliver D, Demiris G, Courtney K. Assessing the nature and process of hospice interdiscplinary team meetings. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2007;9(1):17–21. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wittenberg-Lyles E, Parker Oliver D, Demiris G, Burt S, Regehr K. Inviting absent members: examining how caregivers participation affects hospice team communication. Palliative Medicine. 2010;24(2):192–5. doi: 10.1177/0269216309352066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saltz CC, Schaefer T. Interdisciplinary teams in health care: Integration of family caregivers. Social Work in Health Care. 1996;22(3):59–69. doi: 10.1300/J010v22n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parker Oliver D, Demiris G, Wittenberg-Lyles E, Porock D. The use of videophones for patient and family participation in hospice interdisciplinary team meetings: A promising approach. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2010;19(6):729–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2009.01142.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macdonald E, Hermann H, Hinds P, Crowe J, McDonald P. Beyond interdisciplinary boundaries: Views of consumers, carers and non-government organizations on teamwork. Australasian Psychiatry. 2002;10(2) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fischer MA, Schulz JB, Ogletree BT. Future Directions for Families and Professionals In Interdisciplinary Service Delivery. In: Ogletree BT, Fischer MA, Schulz JB, editors. Bridging The Family Professional Gap: Facilitating Interdisciplinary Services for Children with Disabilities. Springfield, Ill: Charles C Thomas; 1999. pp. 258–264. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Broughton F. Conclusions: thoughts of a palliative care user. In: Monroe B, Oliviere D, editors. Patient Participation in Palliative Care: A Voice for the Voiceless. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003. pp. 196–201. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schacht L, Pandiani J, Maynard A. An assessment of parent involvement in local interagency teams. Journal of Child & Family Studies. 1996;5(3):349–54. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andrews J, Seaver E, Whiteley J, Stevens G. Family members as participants on craniofacial teams. Infant-Toddler Intervention: The Transdisciplinary Journal. 1998;8(2):127–34. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vuokila-Oikkonen P, Janhonen S, Saarento O, Harri M. Storytelling of co-operative team meetings in acute psychiatric care. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2002;40(2):189–98. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Axford AT, Askill C, Jones AJ. Virtual multidisciplinary teams for cancer care. Journal of Telemedicine & Telecare. 2002;8(Suppl 2):3–4. doi: 10.1177/1357633X020080S202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parker Oliver D, Porock D, Demiris G, Courtney K. Patient and family involvement in hospice interdisciplinary teams. J Palliat Care. 2005;21(4):270–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kruse R, Parker Oliver D, Wittenberg-Lyles E, Demiris G. Conducting the ACTIVE randomized trial in hospice care: Keys to success. Clinical Trials. 2012;10:160–9. doi: 10.1177/1740774512461858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parker Oliver D, Washington K, Wittenberg-Lyles E, Demiris G, Porock D. They're part of the team:Participant evaluation of the ACTive intervention. Palliative Medicine. 2009;23:549–55. doi: 10.1177/0269216309105725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fox S, Brenner J. Family Caregivers Online. Pew Research Center. 2012 [Google Scholar]