Abstract

Despite ample precedent in theology and social theory, few studies have systematically examined the role of religion in mitigating the harmful effects of socioeconomic deprivation on mental health. The present study outlines several arguments linking objective and subjective measures of financial hardship, as well as multiple aspects of religious life, with psychological distress. Relevant hypotheses are then tested using data on adults aged 18–59 from the 1998 US NORC General Social Survey. Findings confirm that both types of financial hardship are positively associated with distress, and that several different aspects of religious life buffer against these deleterious influences. Specifically, religious attendance and the belief in an afterlife moderate the deleterious effects of financial hardship on both objective and subjective financial hardship, while meditation serves this function only for objective hardship. No interactive relationships were found between frequency of prayer and financial hardship. A number of implications, study limitations, and directions for future research are identified.

Keywords: USA, Mental health, Relative deprivation, Subjective socioeconomic status, Perceived social position, Afterlife, Religion, Buffering

Introduction

A substantial literature documents the positive association between socioeconomic deprivation and psychological distress (Adler & Ostrove, 1999; Marmot & Wilkinson, 1999; Mirowsky & Ross, 2003; Williams & Collins, 1995). Individuals who experience financial hardship tend to suffer from elevated levels of distress because of greater exposure to chronic and acute stressors, including family and relationship problems, trouble paying monthly bills, physical limitations, and poor neighborhood conditions, among others. These individuals are also more vulnerable to the deleterious effects of economic strain because they have fewer and less helpful social ties and support systems, lower levels of self-esteem and personal mastery, and less constructive coping styles and practices.

To date, the literature has focused primarily on “objective” measures of financial hardship, such as low levels of monetary income. However, recent studies have also directed attention toward “subjective” aspects, such as feelings of relative deprivation and subjective class identification (Branscombe, Schmitt, & Harvey, 1999; Crocker, Major, & Steele, 1998; Operario, Adler, & Williams, 2004; Yngwe, Fritzell, Lundberg, Diderichsen, & Burstrom, 2003; Zagefka & Brown, 2005). Research in this bourgeoning area suggests that one’s assessment of their relative location in the socioeconomic hierarchy of society is an important predictor of mental health above and beyond objective factors (Demakakos, Nazroo, Breeze, & Marmot, 2008; Macleod, Davey Smith, Metcalfe, & Hart, 2005). Given that objective and subjective aspects of financial hardship likely compliment each other (Adler, 2006), the present study simultaneously examines both.

A growing literature has also examined links between multiple dimensions of religious involvement and mental health (Ellison, 1991; Krause, 1995; Pargament, 1997; Pescosolido & Georgianna, 1989; Williams, Larson, Buckler, Heckmann, & Pyle, 1991). Although research findings are not unequivocal, the weight of the evidence suggests that various aspects of religion may have salutary implications for mental health (Smith, McCullough, & Poll, 2003). Proposed explanations for these findings center on religion’s ability to reduce exposure to social stressors, provide social and psychological resources to help deal with stressors when they actually are experienced, and to offer distinctive coping styles and practices, among others (Ellison & Levin, 1998).

Surprisingly, however, only a few empirical studies have examined the interface between financial hardship, religion, and mental health (Ellison, 1991; Krause, 1995; Pollner, 1989; Schieman, Nguyen, & Elliot, 2003; Schieman, Pudrovska, & Milkie, 2005), and no studies to date have looked into these relationships with respect to both objective and subjective measures of hardship. This gap in the literature is notable in light of the pervasiveness of deprivation/ compensation logic in much of the social scientific study of religion. From the theoretical classics of Marx (Marx & Engels, 1955) and Weber (1964 [1922]), to the religion–mental health research involving coping (Pargament, 1997), to contemporary theories of religion (Stark & Bainbridge, 1996; Stark & Finke, 2000), a great deal of theory and research has been built on the assumption that religion is particularly salient, and possibly even beneficial, among socially and economically deprived individuals.

Overall, then, the primary focus of this study is to examine the intersection between financial hardship, religion, and mental health, especially the possibility that religious participation might buffer against the deleterious effects of economic strain. This goal is addressed by first outlining a rationale for linking financial hardship with mental health. Specific ways in which multiple dimensions of religious involvement (i.e., organizational participation, non-organizational practices, and the belief in afterlife) may help to mitigate the impact of these deleterious influences on distress are then discussed. Three hypotheses are then derived form this background, and tested using data from the 1998 General Social Survey (GSS), a representative sample of US adults. Implications of these findings are then discussed, and an agenda for future research is outlined.

Theoretical and empirical background

Financial hardship and mental health

Throughout modern industrialized societies, socioeconomic conditions affect the distribution of mental health by shaping: (a) the degree of exposure to social stressors (i.e., chronic and acute conditions that tax individual capacities to respond); and (b) the degree of vulnerability to those stressors (i.e., the quantity and quality of available resources with which individuals can deal with these problems). Persons with relatively low SES tend to confront more chronic and acute stressors compared with their privileged counterparts, and thus, on average, have worse mental health (Miech et al., 1999; Pearlin, Lieberman, Menaghan, & Mullen, 1981; Williams & Collins, 1995).

To date, most research in this area has focused on “objective” measures of SES, such as personal income, and explanations have centered on the presence or absence of material, social, and psychological resources. For example, individuals with inadequate financial resources are more prone to face difficulties in meeting personal or family needs, paying bills, and obtaining mental or physical health care, as well as lower risk of legal, interpersonal, familial, and other types of stressors. At the same time, these individuals also tend to possess smaller, less diverse social networks from which to obtain emotional, tangible, and informational assistance that could help them to resolve problems and manage the emotional consequences of life’s difficulties. In addition, these individuals typically suffer from deficiencies in psychological and cognitive resources, such as feelings of low personal control, efficacy, and self-worth, which likely impede successful coping and resilience in the face of stressors (Mirowsky & Ross, 2003). For these reasons, individuals with low SES commonly suffer from financial hardship and elevated levels of psychological distress.

In addition to objective measures of hardship, a growing number of studies have focused on “subjective” aspects as well, including feelings of relative deprivation and subjective class identification (Adler, Epel, Castallazzo, & Ickovics, 2000; Boyle, Norman, & Rees, 2004; Macleod et al., 2005; Singh-Manoux, Marmot, & Adler, 2005; Walker & Smith, 2002). Research in this area suggests that social comparisons based on one’s perceptions of their relative position in the socioeconomic hierarchy of society predict psychological well-being net of objective factors. Recent work has shown that subjective assessments of one’s financial condition are influenced, but not entirely predicted, by one’s occupational position, education, household income, satisfaction with their standard of living, past financial experiences, and feelings of financial security regarding the future (Singh-Manoux, Adler, & Marmot, 2003). In essence, these aspects of financial hardship may have at least some independent effects on mental health net of objective measures, and thus may compliment them when studied simultaneously (Adler, 2006). Given the relative neglect of this aspect of financial hardship in the literature, a detailed examination is required here.

As discussed in self-determination theory, individuals in the United States and other capitalist societies are often socialized to regard material gain (e.g., wealth, possessions, luxurious lifestyles) as indicators of success and worth (Kasser & Ryan, 1993). Those persons who perceive—rightly or wrongly—that they are failing to compete successfully for these resources, and to maintain or enhance their material quality of life relative to those of persons in their reference group(s) (e.g., friends, coworkers, neighbors, others), may be prone to experience emotional disturbance. Indeed, a growing body of evidence associates subjective social class with a diverse array of mental health outcomes, including levels of chronic stress (Adler et al., 2000), psychosomatic stress symptoms (Walker & Mann, 1987), depression (Singh-Manoux et al., 2003), negative affectivity and pessimism (Adler et al., 2000), and life satisfaction (Zagefka & Brown, 2005).

The literature suggests at least two sets of possible explanations for the linkage between subjective socioeconomic conditions and mental health. One line of argument centers on the mediating role of self-perceptions, particularly feelings of self-esteem (i.e., one’s intrinsic moral self-worth) and personal control (i.e., one’s ability to manage personal affairs and life direction) (Branscombe et al., 1999; Crocker et al., 1998). Briefly, individuals who feel a sense of relative deprivation or material failure may come to doubt their value and significance as individuals. They may believe—whether accurately or not—that persons around them regard them as unaccomplished and unworthy, and perhaps deserving of their diminished social standing. In turn, these negative reflected appraisals and unfavorable social comparisons may undermine mental well-being. In addition, individuals with low subjective SES may come to doubt their abilities and competence. Because they perceive that their efforts have failed to produce comparative financial or career success, they may question their capacity to achieve important life goals for themselves or their families in the future—e.g., long-term material quality of life, improved economic prospects, and independence. Several previous studies document links between subjective SES and the sense of control (Adler et al., 2000; Mirowsky & Ross, 2003). Moreover, both self-esteem and perceived control are well-established predictors of mental health outcomes (Mirowsky & Ross, 2003; Singh-Manoux, Adler, & Marmot, 2003).

A second set of explanations focuses on affective responses to (real or perceived) deprivation. Consistent with the arguments of equity theory, individuals with low subjective SES are likely to experience a range of negative emotions, such as anger, resentment, shame, guilt, and/or anxiety, among others—common results of perceived inequity and unfairness in the way in which societal resources and rewards are distributed (Van Willigen & Drentea, 2001; Zagefka & Brown, 2005). Importantly, the literature almost unequivocally shows that negative emotions such as these have deleterious effects on mental health (Mirowsky & Ross, 2003).

Overall, then, the literature suggests that both objective and subjective aspects of socioeconomic deprivation may contribute, in somewhat unique ways, to individual variation on a variety of mental health outcomes including psychological distress. As discussed below, religious involvement also appears to influence levels of distress, and there is good reason to believe that multiple aspects of religious life may mitigate the deleterious effects of financial hardship on mental health.

Religion and mental health

For nearly half a century, social scientists have recognized that religion is a complex, multidimensional phenomenon, and consequently that various facets of religious involvement may differ in their association with a given outcome of interest (Levin, Taylor, & Chatters, 1995). In studies of religion and mental health, three of the most important dimensions of religiousness have been: (a) organizational involvement, often gauged in terms of attendance at worship services and/or other congregational activities; (b) non-organizational involvement, including prayer, meditation, scriptural study, and/or other devotional practices; and (c) beliefs and ideologies, often tapped via items on core doctrinal issues, such as beliefs about scriptural interpretation, the nature of God, the existence of an afterlife, and other aspects of belief (Ellison & Levin, 1998; Levin et al., 1995).

Why might organizational religious involvement be linked with distress? Briefly, religious congregations are network-driven institutions; new members are often recruited through pre-existing social ties (e.g., friends, neighbors, coworkers, etc.) (Sherkat & Wilson, 1995), and congregations promote the establishment and cultivation of interpersonal relationships (Cornwall, 1987; Olson, 1989). Indeed, churches and synagogues bring together individuals and families with common interests and activities, as well as shared convictions about matters of faith and fundamental human values, on a regular basis for the purpose of engaging in rituals and other pursuits that have special significance and sacred meaning (Ellison, 1991; Pescosolido & Georgianna, 1989). Further, religious activities (e.g., worship, classes, retreats and small group experiences) offer settings in which participants may disclose intimate, deeply personal issues in a climate of mutuality and trust (Wuthnow, 1994). At their best, these features of congregational life may promote a sense of belonging and support. Organizational religious activities may also reinforce personal faith, and can strengthen religious plausibility structure and meaning systems via which individuals organize and interpret their affairs (Berger, 1967; Williams et al., 1991). All of this may reduce distress.

Non-organizational aspects of religious practice may also have important psychosocial correlates and sequelae, for several reasons. For many persons, practices such as prayer, meditation, and reading religious scriptures and other materials are central to the construction of an individual relationship with a perceived divine other (God) (Poloma & Gallup, 1991; Wikstrom, 1987). That is, individuals develop images and understandings of the nature of the divine from stories, parables, and accounts of the experiences of historical and contemporary figures, and they construct a relationship with the divine via sequential interaction, often experienced as an ongoing conversation (Pollner, 1989). In this way, individuals may come to identify their own situations with those of biblical or historical figures, and through this process of religious role-taking, they may develop perceptions of what types of attitudes, decisions, and behaviors are desired or required of them (Pollner, 1989; Sunden, 1965; Wikstrom, 1987). Thus, individuals who pray or meditate frequently may enjoy (what they experience as) a personal connection with a divine other who can be engaged and relied upon for guidance or solace (Idler, 1995). This may be a potent psychosocial asset, providing a sense of (vicarious) power, feelings of intrinsic self-worth, hope and optimism, and other internal resources that impede distress.

Religious beliefs, particularly the belief in an afterlife, may also influence emotional well-being. Although images of an afterlife vary widely across religious traditions—and indeed, among individuals—many persons envision an afterlife in highly favorable terms, e.g., as a life of spiritual union with God, or reunion with loved ones, or an existence filled with sensory pleasure and delight. For Christians, the promise of eternal life is extended via divine grace for persons who repent and have faith. This belief anchors a powerful worldview within which individuals may interpret their personal circumstances. Terror management theory is important here (Dechesne et al., 2003). Essentially, “literal immortality seeking,” as represented by a strong belief in an afterlife, may help to shift one’s focus away from economic success in this world, and toward the better life that awaits in the afterlife. Thus, the assurance of eternal life may provide a new perspective on worldly existence; for believers, the gift of such an afterlife is the ultimate symbol of divine love, caring, and engagement with creation. For these reasons, believers often report greater hopefulness, happiness, and life satisfaction than other persons (Ellison, Boardman, Williams, & Jackson, 2001; Murphy et al., 2000). Recent studies have even reported that the belief in an afterlife is associated with lower levels of mental disturbance, including depression, anxiety, anger, and paranoid ideation, among others (Flannelly, Koenig, Ellison, & Galek, 2006).

The interactive influence of financial hardship and religion on mental health

Thus far it has been argued that both objective and subjective aspects financial hardship may lead to psychological distress, and that multiple dimensions of religious involvement (e.g., organizational, non-organizational, belief) may contribute to lower levels of distress. It is also important to consider the possibility that religious involvement—by providing social, psychological, and cognitive resources that may make socioeconomic deprivation easier to bear emotionally—may be especially helpful for persons suffering from financial hardship. In other words, the harmful effects of financial hardship may be reduced at high levels of religious involvement.

There are several reasons to expect that organizational religious involvement (i.e., service attendance) may mitigate the deleterious effects of both objective and subjective financial hardship. First, religious congregations often serve as conduits for formal and informal social and material support (Krause, 2006, 2002). Churches and synagogues offer a range of programs and services targeted at the least fortunate members of the faith and the community (Chaves, 2004). Moreover, congregation members often exchange tangible aid (i.e., goods and services) and socioemotional help (i.e., companionship, morale, and spiritual support) on an informal basis (Krause, 2002; Maton, 1987). Regular churchgoers express greater confidence in the generosity and reliability of their support networks than other persons (Bradley, 1995; Ellison & George, 1994), and there are also signs that they derive greater benefit from the socioemotional support provided by coreligionists, as compared with the support they receive from other (secular) sources (Krause, 2006). Second, for persons suffering from a lack of financial resources, particularly subjective assessments, religious communities may provide new reference groups for comparison that are based on non-competitive, non-material characteristics such as spirituality, wisdom, and kindness (Ellison, 1993). This may be accompanied by messages (e.g., sermons, homilies, other teachings) for members not to judge their fellows on the basis of wealth or social status. Further, the social warmth of congregations may provide positive reflected appraisals, which may be particularly helpful for persons suffering from financial hardship, who may not be treated with respect in other venues (Ellison, 1993). Finally, participation in church activities—e.g., religious education, outreach, programs and charities, etc.—can encourage members to develop talents, leadership skills, and other abilities (e.g., Ellison, 1993; Verba, Scholzman, & Brady, 1995), perhaps boosting feelings of competence and mastery that are eroded by low SES. Thus, in several ways organizational religious involvement may be emotionally beneficial for economically deprived persons.

Non-organizational religious practices such as prayer and meditation may also help these individuals in several ways. First, the perception that one enjoys a personal relationship with a higher power that (a) is engaged directly in human affairs, (b) intervenes on behalf of individuals, (c) desires a unique connection with each person, and (d) has a plan and purpose for each person is likely to enhance feelings of intrinsic moral self-worth (e.g., Ellison, 1993; Pargament, 1997). To the extent that prayer and devotional pursuits strengthen such perceptions, they may be particularly important for persons experiencing financial hardship. Second, such perceived relationships are likely to provide a sense of divine (i.e., vicarious or secondary) control. Although these individuals may lack the power to control their own affairs, they can take comfort that a benevolent deity is in charge (Krause, 2005; Schieman et al., 2005). Third, these individuals may benefit from their feelings of secure attachment to a caring, responsive divine other; indeed, some researchers have described a loving God as “the ultimate attachment figure,” who may function as a “haven of safety” in a distressing world (e.g., Granqvist, 1998; Granqvist & Hagekull, 1999; Kirkpatrick, 2005). Prayer and meditation along these lines may help persons experiencing financial hardship, by shifting attention away from personal struggles and financial hardship and toward spiritual matters.

Belief in an afterlife may also be psychologically valuable for persons experiencing financial hardship. First, this conviction provides a sense of enduring, eternal significance that transcends the frustrations and failures of this life (Dworkin, 2000; Exline, 2002; Flynn & Kunkel, 1987; Smith, Range, & Ulmer, 1991–1992). As critical theorists have long recognized, the promise of future spiritual rewards allay the resentments and concerns of even those persons who have been mistreated, or who have been unsuccessful in the competitive struggle for material resources (Freud, 1961 [1927]; Marx & Engels, 1955; Schieman et al., 2003; Weber, 1964 [1922]). Second, the promise of eternal life offers an alternative perspective by which to interpret one’s earthly circumstances. Slights and insults due to financial hardship may be less threatening to the sense of self because they are seen as ephemeral, whereas eternal life offers spiritual riches that will last forever (Ellison et al., 2001). Third, belief in an afterlife may change the way one experiences daily life. For persons who experience financial hardship, everyday life may seem unrewarding and frustrating. However, for those who believe in an afterlife, even small opportunities or rewards may be interpreted as blessings from by God. It may be easier to detach from routine competition for material or social rewards, and to view earthly existence as unfolding in accordance with God’s plan. In these ways, belief in an afterlife may mitigate the harmful emotional effects of socioeconomic deprivation.

Hypotheses

Hypothesis 1: Financial hardship (both objective and subjective) will be positively associated with psychological distress.

Hypothesis 2: Religious involvement (i.e., religious service attendance, prayer, meditation, and the belief in an afterlife) will be inversely associated with psychological distress.

Hypothesis 3: Religious involvement will moderate (i.e., buffer against) the effects of financial hardship on psychological distress.

Methods

To test these hypotheses, Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression techniques were used to analyze data from the 1998 General Social Survey (Davis, Smith, & Marsden, 1998), a nationally representative cross-sectional survey of US adults conducted by the National Opinion Research Center (NORC). The GSS has involved a sample (76% response rate) of approximately 1500 persons every year between 1972 and 1993 (except for 1979 and 1981), and a sample of approximately 3000 persons in even-numbered years only beginning in 1994. However, the 1998 data was employed here because this is the only year in which the GSS included a special module of items tapping psychological distress, as well as the requisite religious items, SES measures, and control variables needed for this study. Since 1987, the GSS has employed a split ballot design, such that many sets of items—including the battery of questions dealing with psychological distress in the 1998 survey—were only asked of a randomly-selected subset of the 3000 respondents. For this reason, the effective sample size used here was much smaller than the size of the total GSS sample. Nevertheless, the ballots were assigned randomly, and ancillary analyses confirmed that this practice was not a source of bias here. The effective N was 1140 after a small number of cases were handled via listwise deletion.

The outcome measure was a six-item mean index (alpha = 0.836) of psychological distress (Kessler et al., 2002). Respondents were asked the following six questions: “In the past 30 days, about how often did you feel: (1) so sad nothing could cheer you up, (2) nervous, (3) restless or fidgety, (4) hopeless, (5) that everything was an effort, and (6) worthless.” Each component of this index is coded: 1 = none of the time, 2 =a little bit of the time, 3 = some of the time, 4 =most of the time, and 5 = all of the time. To reduce the skewed nature of this variable (skewness = 1.165), a square root transformation was performed prior to the regression analyses (Hamilton, 1992).

Objective financial hardship was gauged with personal income. To tap stressful levels of income that may cause financial strain and psychological distress, a dummy variable indicating respondents who were in the lowest quartile of the income distribution was employed. This measure explained roughly the same amount of the variation (R2 = 0.048) on psychological distress as the continuous version (R2 = 0.052), and all findings were essentially the same when the continuous measure was employed. Subjective financial hardship was gauged with a measure of perceived income or relative deprivation where respondents were asked: “Do you think your income is (1) far below average, (2) below average, (3) average, (4) above average, or (5) far above average?” Ancillary analyses (not shown) indicated that these five categories could be collapsed into a dichotomous variable where individuals who reported that their incomes were either far below or below average (coded as 1) were compared with those who reported that their incomes were average, above average, or far above average (coded as 0). This measurement scheme explained as much of the variation on distress as other possible codings, such as treating it as a continuous measure or using five dummy variables.

Religious independent variables included a measure of organizational involvement (i.e., religious service attendance). Respondents were asked: “How often do you attend religious services (0 =never, 1 = less than once a year, 2= about once or twice a year, 3 = several times a year, 4 = about once a month, 5 = 2–3 times a month, 6 = nearly every week, 7 = every week, and 8 = several times a week)?” Two measures of non-organizational religious practices were used. For the prayer variable, coded 1 = never, 2 = less than once a week, 3 = once a week, 4 = several times a week, 5 = once a day, and 6 = several times a day, respondents were asked: “About how often do you pray?” For the meditation variable, coded 1 = never, 2 = less than once a month, 3 = once a month, 4 = a few times a month, 5 = once a week, 6 = a few times a week, 7 = once a day, and 8 = more than once a day, respondents were asked: “Within your religious or spiritual tradition, how often do you meditate?” To gauge the belief in an afterlife variable, respondents were asked: “Do you believe in an afterlife?” This was a dummy variable that was coded 1 if the respondent definitely believed in an afterlife, and 0 if they did not believe or were not sure.

Cross-product terms were constructed for each of the four religion variables and both of the financial hardship measures. This provided eight different interaction terms for analysis. To reduce multicolinearity, all continuous/ordinal religion variables (i.e., attendance, prayer, and meditation) were zero-centered prior to the construction of these interaction terms (Aiken & West, 1991).

Important control variables included: age (in years), gender (female = 1), marital status (married = 1), race/ethnicity (black =1), region of residence (south = 1), and urban/rural (coded 1–10, where 1 is a large central city and 10 is open country). All of analyses also contained a control for educational attainment using a dichotomous variable for individuals with less than a high school diploma. Each of these variables was included in all models to adjust for factors that may be related to the independent and dependent variables employed here.

Results

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for all of the variables used in this analysis. The mean for the dependent variable, psychological distress, was 1.902, meaning that individuals in the sample felt distressed slightly less than some of the time (2.00 would be exactly some of the time), on average. Since this variable is skewed, a transformed (square root) version was used for all subsequent regression analyses. The 24% on the objective financial hardship variable represents the bottom quartile of the personal income distribution, while 30.6% of the respondents reported that their income is either far below or below average, which is the subjective financial hardship measure. GSS respondents appear to be only moderately engaged in religion. The average respondent attended religious services slightly less than once per month, prayed privately a few times a week, and meditated less than once a month. However, a large majority of respondents (81.7%) reported believing in an afterlife. The mean age is 45, 55% are females, 13% are black, and 47% are married. Roughly 17% of the sample did not graduate from high school.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

| Mean | Std. dev. | Min–max | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological distress | 1.902 | 0.733 | 1–5 |

| Objective financial hardship | 0.241 | – | 0–1 |

| Subjective financial hardship | 0.306 | – | 0–1 |

| Religious attendance | 3.797 | 2.772 | 0–8 |

| Prayer | 4.327 | 1.491 | 1–6 |

| Meditation | 3.456 | 2.731 | 1–8 |

| Afterlife | 0.817 | – | 0–1 |

| Age | 45.110 | 16.598 | 18–89 |

| Female | 0.546 | – | 0–1 |

| Black | 0.134 | – | 0–1 |

| Married | 0.474 | – | 0–1 |

| South | 0.362 | – | 0–1 |

| Urban/rural | 4.012 | 2.661 | 1–10 |

| Education | 0.174 | 0.379 | 0–1 |

Table 2 provides bivariate associations between the key study variables. As expected, both objective (r = 0.220) and subjective (r = 0.209) measures of financial hardship have moderate positive correlations with psychological distress. For the religion measures, only service attendance (r = −0.149) appears to be correlated with distress, and this relationship is negative, as expected. Objective and subjective financial hardship are not highly correlated with each other (r = 0.337), suggesting that these two measures are largely tapping unique aspects of economic strain. Each explains less than 11% of the variation in the other. The correlation between the religion measures ranges from 0.138 for meditation and the belief in an afterlife, to 0.552 for attendance and prayer. There are only weak correlations between religion and financial hardship.

Table 2.

Bivariate associations.

| Psychological distress | Objective financial hardship | Subjective financial hardship | Religious attendance | Prayer | Meditation | Afterlife | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological distress | 1.000 | ||||||

| Objective financial hardship | 0.220 | 1.000 | |||||

| Subjective financial hardship | 0.209 | 0.337 | 1.000 | ||||

| Religious attendance | −0.149 | −0.046 | −0.100 | 1.000 | |||

| Prayer | −0.019 | 0.081 | 0.080 | 0.552 | 1.000 | ||

| Meditation | −0.010 | 0.068 | 0.017 | 0.374 | 0.459 | 1.000 | |

| Afterlife | −0.042 | −0.030 | 0.010 | 0.188 | 0.259 | 0.138 | 1.000 |

Table 3 provides the results from the multivariate models. Model 1 shows the results for both objective and subjective financial hardship, controlling for the effects of each other, as well as covariates (not shown) including age, gender, marital status, region of country, urban versus rural residency, and educational attainment. These findings show that both measures of strain are positively associated with distress net of each other. More specifically, having an income in the lower quartile of the distribution is associated with higher levels of distress compared with an income in the top three quartiles. Likewise, reporting that your income is either far below or below average is associated with higher levels of distress compared with those who believe that their income is average, above average, or far above average. These findings provide strong support for Hypothesis 1.

Table 3.

OLS parameter estimates from the regression of financial hardship, religion, and financial hardship × religion on psychological distress (N = 1140).

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Objective financial hardship | 0.081*** | 0.078*** | 0.074*** | 0.078*** | 0.080*** | 0.154*** | 0.080*** | 0.080*** | 0.078*** | 0.079*** |

| Subjective financial hardship | 0.074*** | 0.066*** | 0.067*** | 0.066*** | 0.069*** | 0.068*** | 0.063*** | 0.066*** | 0.067*** | 0.129*** |

| Religious attendance | – | −0.011** | −0.008* | −0.011** | −0.011** | −0.011** | −0.007+ | −0.011** | −0.011** | −0.011** |

| Prayer | – | 0.011+ | 0.011+ | 0.011+ | 0.011+ | 0.010+ | 0.010 | 0.011+ | 0.012+ | 0.010 |

| Meditation | – | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.008 | 0.005+ | 0.004 | 0.006+ | 0.005 | 0.005 |

| Afterlife | – | −0.014 | −0.015 | −0.014 | −0.012 | 0.011 | −0.015 | −0.014 | −0.015 | 0.010 |

| Objective financial hardship × religious attendance | – | – | −0.011* | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Objective financial hardship × prayer | – | – | – | −0.002 | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Objective financial hardship × meditation | – | – | – | – | −0.012* | – | – | – | – | – |

| Objective financial hardship × afterlife | – | – | – | – | – | −0.097* | – | – | – | – |

| Subjective financial hardship × religious attendance | – | – | – | – | – | – | −0.013* | – | – | – |

| Subjective financial hardship × prayer | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | −0.004 | – | – |

| Subjective financial hardship × meditation | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | −0.004 | – |

| Subjective financial hardship × afterlife | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | −0.077* |

| Intercept | 1.457*** | 1.467*** | 1.469*** | 1.469*** | 1.466*** | 1.447*** | 1.470*** | 1.470*** | 1.470*** | 1.446*** |

| R2 | 0.108 | 0.116 | 0.118 | 0.115 | 0.119 | 0.120 | 0.120 | 0.116 | 0.115 | 0.118 |

Notes: Psychological distress is square-root transformed. All models are net of adjustments for age, gender, race, marital status, region, city size, and education. All continuous/ ordinal religion variables (i.e., attendance, prayer, and meditation) were zero-centered prior to the construction of interaction terms.

p< 0.001,

p<0.01,

p< 0.05,

p <0.10.

Model 2 provides a test of Hypothesis 2, which stated that religious involvement would be inversely associated with distress. The findings show that service attendance is indeed inversely associated with psychological distress, but that neither meditation nor the belief in an afterlife is significantly associated with this outcome. Prayer, on the other hand, bears a slight positive association with distress, although this finding is only moderately significant. This likely indicates reverse causation, where financial hardship leads to higher levels of prayer, a finding that has already been documented in the literature. Thus, these findings provide support for Hypothesis 2 for service attendance, but not for the other measures of religion employed here.

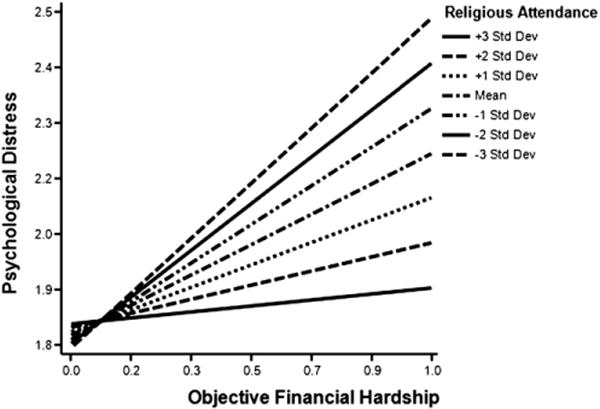

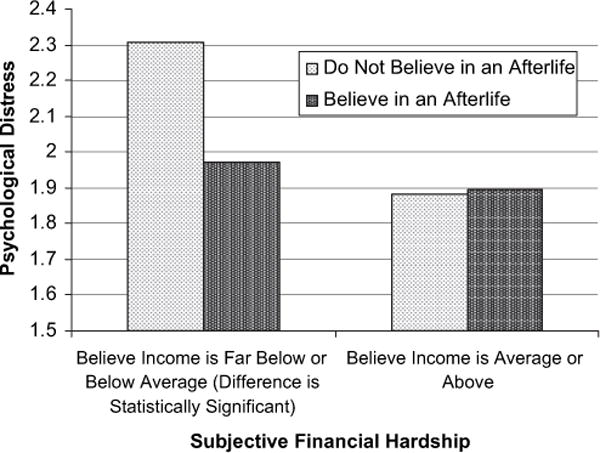

Models 3–10 provide tests of Hypothesis 3, which stated that religious involvement will moderate (i.e., buffer against) the deleterious effects of financial hardship on psychological distress. Model 3 examines this possibility for objective financial hardship and religious attendance, and the findings support this proposition. The interaction term for these two independent variables is statistically significant, indicating that the positive association between having an income in the lowest quartile and psychological distress is attenuated as levels of religious attendance increase. Additional analyses reveal that the positive association between low income and distress occurs primarily among individuals who have average levels of attendance or less. For those that attend frequently, there is virtually no association between low income and distress. These findings are displayed graphically in Fig. 1 using the non-transformed version of the dependent variable. While prayer does not appear to serve a similar function, both meditation (Model 5) and the belief in an afterlife (Model 6) also moderate the effects of objective financial hardship on psychological distress (as indicated by the statistically significant interaction terms in Models 5 and 6). The findings for meditation look very similar to the ones for attendance shown in Fig. 1, whereas the ones for the belief in an afterlife resemble the ones shown in Fig. 2 (below) for subjective financial hardship.

Fig. 1.

The interactive influence of objective financial hardship and religious attendance on psychological distress.

Fig. 2.

The interactive influence of subjective financial hardship and the belief in an afterlife on psychological distress.

In addition to these findings for objective financial hardship, it is also possible that religious involvement buffers against the distressing effects of subjective hardship. Models 7–10 examine this possibility. In Model 7 we see that the interaction term between subjective financial hardship (i.e., reporting that one’s income is either far below or below average) and religious attendance is indeed statistically significant. This indicates that the positive association between perceived hardship and distress is reduced at higher levels of attendance, which means that attendance is providing a buffering effect. These findings look very similar to the ones for objective hardship, which are shown in Fig. 1. For subjective hardship, neither prayer nor meditation serves this function, but the belief in an afterlife does. In Model 10, the interaction term for subjective financial hardship and this religious belief is statistically significant, suggesting that believing in an afterlife reduces the harmful effects of financial strain in this life. This finding is displayed graphically in Fig. 2. Overall, these results provide strong support for Hypothesis 3.

Discussion

Although investigators have long been aware of socioeconomic variations in mental health, only recently have studies examined both objective (i.e., income) and subjective (i.e., feelings of relative financial deprivation or privilege) aspects of financial hardship (Hu, Alder, Goldman, Weinstein, & Seeman, 2005; Mirowsky & Ross, 2003; Operario et al., 2004). Moreover, although a growing body of work links religious involvement with mental health, there has been little sustained interest in the interaction of financial hardship and religion in shaping psychosocial outcomes (Ellison, 1991; Krause, 1995; Pollner, 1989; Schieman et al., 2003). Therefore, this study contributes to the literature by: (a) examining the effects of both objective and subjective financial hardship on psychological distress; and (b) exploring the roles of multiple dimensions of religious involvement in moderating or buffering the links between financial hardship and psychological distress.

Several findings reported here are noteworthy. First, the analyses provide clear evidence that both objective and subjective aspects of financial hardship (i.e., low levels of monetary income and personal assessments of one’s place in the economic hierarchy of society) are associated with distress independent of one another. The importance of subjective hardship is important because in a competitive socioeconomic system, such as the one that exists in the United States, people are often judged by their material credentials: wealth and possessions, standards of living and lifestyles. Individuals who feel that they have fallen behind others in their community or reference groups in achieving these ends tend to experience strain, frustration, and anxiety. This perception of relative deprivation is likely to challenge fundamental notions of the self—i.e., as competent, efficacious, worthwhile, and able to provide adequately for oneself and one’s family. Such painful feelings of inadequacy and uncertainty can take a significant toll on psychological functioning.

Regarding direct associations between multiple dimensions of religious involvement and distress, the findings are decidedly mixed. On the one hand, consistent with a number of previous studies (Smith et al., 2003), the frequency of religious attendance is inversely linked with distress. As discussed earlier, several aspects of organizational religious involvement may facilitate mental health, including the access to friendships, support systems, and feelings of community, as well as the reinforcement of worldviews and plausibility structures that can result from regular ritual participation. On the other hand, the frequency of prayer is moderately positively associated with distress. Although it is possible that prayer may exacerbate intrapsychic difficulties, it is also possible that persons experiencing high levels of distress may simply pray more often as a coping mechanism. At the present time, the causal order between prayer and distress is not well understood, and future work with longitudinal data will be required to address this issue. In the models, neither frequency of meditation nor belief in an afterlife bears a direct association with psychological distress.

Perhaps the most novel and important findings in this study involve the interactive effects of both objective and subjective financial hardship and religious involvement on distress. Briefly, the results show that religious service attendance and the belief in an afterlife (and to a lesser extent meditation) buffer the deleterious effects of financial hardship on psychological distress. For service attendance, it is possible to speculate that involvement in the activities of a religious congregation may provide several benefits for persons experiencing real or perceived economic deprivation. For example, religious congregations may provide much needed material support during times of need that may help to buffer against objective hardship. Religious messages and teachings, as well as emotional support from coreligionists, may also help deprived individuals to reframe their circumstances in terms that are less threatening to the sense of self, and hence less emotionally damaging, which may help to offset perceived financial deprivation (Idler, 1995; Pargament, 1997). They may also shift the focus of attention and energy away from competition for material success or prestige to other types of life goals and purposes. In addition, congregations may tend to encourage nonmaterial standards for evaluating the self and others—e.g., personal spirituality, character, or prosocial conduct. Faith communities may also mitigate feelings of perceived hardship by providing social warmth and positive reflected appraisals, thereby bolstering feelings of self-worth, personal efficacy, hope, and optimism (Ellison & Levin, 1998; Koenig, 1994; Krause, 2005, Schieman et al., 2005).

The results also indicate that the belief in an afterlife (a neglected facet of the religion-health connection) mitigates the deleterious effects of both objective and subjective financial hardship on distress. These findings are consistent with a long tradition of theory suggesting that otherworldly rewards—e.g., the promise of a better future life, usually depicted as both eternal and glorious—can compensate individuals emotionally for the strains and hardships, both objective and subjective, experienced in their present life (Flynn & Kunkel, 1987; Smith et al., 1991–1992). Elements of Christian teaching, to which many GSS respondents appear to subscribe, also hint at a reversal of fortunes in the afterlife (e.g., “the first shall be last and the last shall be first,” as stated in Matthew 20:16 of the Bible) that may hold particular appeal to persons who have been (or feel that they have been) unjustly deprived or mistreated in this world. Given these promises of future glory for the faithful, believers may be less prone to take current deprivations to heart, as threats to personal identity or the sense of self; rather, they may construct their “true” identity in religious or spiritual terms (e.g., as Christians, children of God, etc.). Moreover, belief in an afterlife may also signal a changed, and perhaps enriched, perspective on this-worldly existence. To the extent that believers adopt a worldview that diminishes the importance of their current socioeconomic status, they may experience patience, gratitude, and hopefulness. Meditation may also serve such a function, but prayer does not appear to play this role.

Taken together, these findings underscore an important contingent aspect of the link between religious faith and psychological well-being: Service attendance and the belief in an afterlife (and to a lesser extent, meditation) appear to function as significant emotional compensators, or “consolation prizes,” for persons who are experiencing real or perceived financial deprivation. Clearly, this implies that there are multiple pathways to emotional health, and that the absence of financial resources does not necessarily translate into an elevated level of emotional disturbance. Although there is a rich and ample theoretical basis for such a finding, this particular type contingent relationship has been neglected in most previous work.

Despite the advances made in this study, there are also several limitations that bear mentioning. First, and most obviously, the GSS data are cross-sectional, and this makes it impossible to establish the causal direction of these relationships conclusively. It will be important to confirm the patterns identified here using longitudinal data in the future, especially with respect to the correlation between subjective financial hardship and distress, since this relationship could be reciprocal and affected by response bias (Garbarski, 2010). The findings for prayer were discussed above, but it is also possible that psychological distress is inversely associated with financial hardship. Our theory predicts a connection between hardship and distress, but the reverse is also possible as well. Second, although our study has offered a number of plausible, albeit speculative, explanations for the main and buffering effects of religious involvement, the limits of the GSS data do not allow these to be confirmed. Further research is needed in which investigators build in these hypothesized intervening constructs, including self-esteem, efficacy or mastery, hopefulness and optimism, and others. This will help clarify the reasons and mechanisms underlying the observed role of these stress-buffering effects of religion. Third, the GSS includes data on belief in an afterlife, but not on the content of the respondents’ images of this afterlife (Flynn & Kunkel, 1987). Although there is some evidence that specific notions about the afterlife vary—even among adherents to the same religious tradition, such as Christianity—this issue has received little sustained attention from researchers. It would be valuable to know whether, and to what extent, certain ideas and images of the afterlife provide greater psychosocial benefits than others, and under what circumstances these salutary effects may emerge. This, too, is an important and promising direction for future exploration.

Another important issue to consider is the linkage between subjective assessments of financial hardship and subjective self-reports of psychological distress because reporting bias and reciprocal relationships may inflate the correlation between these variables (Garbarski, 2010). While this may be a problem, the fact that the results reported here are similar for both objective and subjective financial hardship lends credibility to arguments concerning the importance of each. Given that these two measures of SES likely tap at least some unique aspects of financial hardship (Leu et al., 2008), showing that each has an effect on distress net of the other and is moderated by multiple aspects of religious life provides valuable insight into the diverse material and psychosocial causes of distress.

The connection between objective and subjective financial SES needs additional attention as well because we currently do not know exactly what measures of subjective social position are tapping. We know that they are correlated with more traditional measures of SES such as income and education, but we also know that these measures do not offer complete explanations. Some have argued that measures of subjective social status tap the “cognitive averaging” of SES and other social characteristics (Demakakos et al., 2008; Garbarski, 2010), but exactly what these “other characteristics” might be is not known. Here, the correlation between objective and subjective financial hardship was 0.337, meaning that the former explains only about 11% of the variation on the latter. Future research should seek to better understand the causes of subjective SES.

It is also important to note that the conceptualization and measurement of religion in this study is based largely on the Judeo-Christian tradition. This is due to necessity, since the sample was randomly drawn from the US population, which is predominately Christian. The measure of meditation could help to tap the practices of several Eastern traditions including Buddhism, but given how rare these religions are in the sample, this is likely relevant for only a very small minority of the population. Future research should certainly seek to examine the issues raised here for other religious traditions, and in other areas throughout the world.

Despite these limitations, this study has made a significant contribution to the literature on SES, religion, and mental health by: (a) demonstrating the important and unique relationship between subjective and objective measures of financial hardship; and (b) revealing the role of some (but not all) facets of religiondand especially the neglected dimension of belief (particularly ones concerning the afterlife)—in buffering the harmful effects of economic strain on mental health. The apparent salutary relationship between religious involvement and psychological well-being varies by the specific aspect of religion that is considered. Future research on religion and health, and perhaps other outcomes as well, should pay close attention to the contingent nature of such relationships, focusing in particular on the ways in which they vary according to SES and other facets of one’s location in the social order.

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this paper was presented at 2003 meetings of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion, Norfolk, Virginia. This research was partly supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging and the Lilly Endowment to the second author. However, the authors alone are responsible for any errors or shortcomings.

References

- Adler NE. When one’s main effect is another’s error: material vs. psychosocial explanations of health disparities. A commentary on Macleod et al. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;63:846–850. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler NE, Epel E, Castallazzo G, Ickovics J. Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning in preliminary data in healthy white women. Health Psychology. 2000;19:586–592. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.6.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler NE, Ostrove JM. Socioeconomic status and health: what we know and what we don’t. Annals of New York Academy of Sciences. 1999;896:3–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Berger P. The sacred canopy. Doubleday; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle P, Norman P, Rees P. Changing places. Do changes in the relative deprivation of areas influence limiting long-term illness and mortality among non-migrant people living in non-deprived households? Social Science & Medicine. 2004;58:2459–2471. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley DE. Religious involvement and social resources: evidence from the data set “Americans’ Changing Lives. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1995;34:259–267. [Google Scholar]

- Branscombe NR, Schmitt MT, Harvey RD. Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African Americans: implications for group identification and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:135–149. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves M. Congregations in America. Harvard University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall M. The social bases of religion: a study of the factors influencing religious beliefs and commitment. Review of Religious Research. 1987;29:44–56. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Major B, Steele C. Social stigma. In: Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, Lindzey G, editors. The handbook of social psychology. Oxford University Press; 1998. pp. 504–553. [Google Scholar]

- Davis JA, Smith TA, Marsden PV. General social surveys, 1972–1998 cumulative codebook. Chicago: National Opinion Research Center; 1998. Distributed by Interuniversity Consortium for Political and Social Research [ICPSR], Ann Arbor, MI, and Roper Center, Storrs, CT. [Google Scholar]

- Dechesne M, Pyszczynski T, Arndt J, Ransom S, Sheldon KM, van Knippenberg A, et al. Literal and symbolic immortality: the effect of evidence of literal immortality on self-esteem striving in response to mortality salience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:722–737. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demakakos P, Nazroo J, Breeze E, Marmot M. Socioeconomic status and health: the role of subjective social status. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67:330–340. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin RW. The new gospel of health. The Public Interest. 2000;141:77–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG. Religious involvement and subjective well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1991;32:80–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG. Religious involvement and self-perception among black Americans. Social Forces. 1993;71:1027–1055. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, Boardman JD, Williams DR, Jackson JS. Religious involvement, stress, and mental health: findings from the 1995 Detroit area study. Social Forces. 2001;80:215–249. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, George LK. Religious involvement, social ties, and social support in a southeastern community. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1994;33:46–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, Levin JS. The religion-health connection: evidence, theory, and future directions.". Health Education and Behavior. 1998;25:700–720. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exline JJ. Stumbling blocks on the religious road: fractured relationships, nagging vices, and the inner struggle to believe. Psychological Inquiry. 2002;13:182–189. [Google Scholar]

- Flannelly KJ, Koenig HG, Ellison CG, Galek KC. Belief in an afterlife and mental health: findings from a national survey. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2006;194:524–529. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000224876.63035.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn CP, Kunkel SR. Deprivation, compensation, and conceptions of an afterlife. Sociological Analysis. 1987;48:58–72. [Google Scholar]

- Freud S. Civilization and its discontents. W.W. Norton and Company; 1961 [1927]. [Google Scholar]

- Garbarski D. Perceived social position and health: Is there a reciprocal relationship? Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70:692–699. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granqvist P. Religiousness and perceived childhood attachment: on the question of compensation or correspondence. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1998;37:350–367. [Google Scholar]

- Granqvist P, Hagekull B. Religiousness and perceived childhood attachment: profiling socialized correspondence and emotional compensation. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1999;38:254–273. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton LC. Regression with graphics. Duxbury Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hu P, Adler NE, Goldman N, Weinstein M, Seeman TE. Relationship between subjective social status and measures of health in older Taiwanese persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53:483–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL. Religion, health, and non-physical senses of self. Social Forces. 1995;74:683–704. [Google Scholar]

- Kasser T, Ryan R. A dark side of the American dream: correlates of financial success as a central life aspiration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;65:410–422. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.2.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand SLT, et al. Short screening scales to monitor the prospective prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32:959–976. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick LA. Attachment, evolution, and the psychology of religion. Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HB. Religion in aging and health: Theoretical foundations and methodological frontiers. Sage; 1994. Religion and hope for the disabled elder. In J. S. Levin (Ed.) pp. 18–51. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Religiosity and self-esteem among older adults. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 1995;50:236–246. doi: 10.1093/geronb/50b.5.p236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Exploring race differences in a battery of church support measures. Review of Religious Research. 2002;44:126–149. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. God-mediated control and psychological well-being in late life. Research on Aging. 2005;27:136–164. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Exploring the stress-buffering effects of church-based and secular social support on self-rated health in late life. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2006;61B:S35–S43. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.1.s35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leu J, Yen IH, Gansky SA, Walton E, Adler NE, Takeuchi DT. The association between subjective social status and mental health among Asian immigrants: investigating the influence of age at immigration. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;66:1152–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin JS, Taylor RJ, Chatters LM. A multidimensional measure of religious involvement among African Americans. The Sociological Quarterly. 1995;36:157–173. [Google Scholar]

- Macleod J, Davey Smith G, Metcalfe C, Hart C. Is subjective social status a more important determinant of health than objective social status: evidence from a prospective observational study of Scottish men. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61:1916–1929. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M, Wilkinson RG. Social determinants of health. Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Marx K, Engels F. On religion. 1955. Foreign Languages Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Maton KI. Patterns and psychological correlates of material support in a religious setting: the bidirectional support hypothesis. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1987;15:185–207. [Google Scholar]

- Miech RA, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Wright BRE, Silva PA. Low socioeconomic status and mental disorders: a longitudinal study of selection and causation during young adulthood. American Journal of Sociology. 1999;104:1096–1131. [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky J, Ross CE. Social causes of psychological distress. Aldine de Gruyter; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy PE, Ciarrocchi JW, Piedmont RL, Cheston S, Peyrot M, Fitchett G. The relation of religious belief and practices, depression, and hopelessness in persons with clinical depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:1102–1106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson DVA. Church friendships: boon or barrier to church growth? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1989;28:432–447. [Google Scholar]

- Operario D, Adler NE, Williams DR. Subjective social status: reliability and predictive utility for global health. Psychology and Health. 2004;19:237–246. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI. The psychology of religion and coping. Guilford; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Lieberman MA, Menaghan EG, Mullen JT. The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1981;22:337–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido BA, Georgianna S. Durkheim, suicide, and religion: toward a network theory of suicide. American Sociological Review. 1989;54:33–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollner M. Divine relations, social relations, and well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1989;30:92–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poloma MM, Gallup GH., Jr . Varieties of prayer: A survey report. Trinity Press International; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Schieman S, Nguyen K, Elliot D. Religiosity, socioeconomic status, and the sense of mastery. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2003;66:202–221. [Google Scholar]

- Schieman S, Pudrovska T, Milkie MA. The sense of divine control and the self-concept. Research on Aging. 2005;27:165–196. [Google Scholar]

- Sherkat DE, Wilson J. Preferences, constraints, and choices in religious markets: an examination of religious switching and apostasy. Social Forces. 1995;73:993–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Singh-Manoux A, Adler NE, Marmot MG. Subjective social status: its determinants and its association with measures of ill-health in the Whitehall II study. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;56:1321–1333. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00131-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh-Manoux A, Marmot MG, Adler NE. Does subjective social status predict health and change in health status better than objective status? Psychosomatic Medicine. 2005;67:855–861. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188434.52941.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PC, Range LM, Ulmer A. Belief in afterlife as a buffer in suicidal and other bereavement. Omega. 1991–1992;24:217–225. [Google Scholar]

- Smith TB, McCullough ME, Poll J. Religiousness and depression: evidence for a main effect and the moderating influence of stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:614–636. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.4.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark R, Bainbridge WS. A theory of religion. Rutgers University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Stark R, Finke R. Acts of faith: Explaining the human side of religion. University of California Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sunden H. What is the next step to be taken in the study of religious life? Harvard Theological Review. 1965;58:445–451. [Google Scholar]

- Van Willigen M, Drentea P. Benefits of equitable relationships: the impact of sense of fairness, household division of labor, and decision making power on perceived social support. Sex Roles. 2001;44:571–597. [Google Scholar]

- Verba S, Scholzman KL, Brady H. Voice and equality: Civic voluntarism in American politics. Harvard University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Walker I, Mann L. Unemployment, relative deprivation, and social protest. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1987;13:275–283. [Google Scholar]

- Walker I, Smith H. Relative deprivation: Specification, development, and integration. Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Weber M. The sociology of religion. Beacon Press; 1964 [1922]. [Google Scholar]

- Wikstrom O. Attribution, roles, and religion: a theoretical analysis of Sunden’s role theory and attributional approach to religious experience. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1987;26:390–400. [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Collins C. US socioeconomic and racial differences in health: patterns and explanations. Annual Review of Sociology. 1995;21:349–386. [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Larson DB, Buckler R, Heckmann R, Pyle C. Religion and psychological distress in a community sample. Social Science & Medicine. 1991;32:1257–1262. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90040-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuthnow R. Sharing the journey. Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Yngwe MA, Fritzell J, Lundberg O, Diderichsen F, Burstrom B. Exploring relative deprivation: is social comparison a mechanism in the relation between income and health? Social Science & Medicine. 2003;57:1463–1473. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00541-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagefka H, Brown R. Comparisons and perceived deprivation in ethnic minority settings. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31:467–482. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]