Abstract

The present study reports a human case of cutaneous gnathostomiasis with recurrent migratory nodule and persistent eosinophilia in China. A 52-year-old woman from Henan Province, central China, presented with recurrent migratory reddish swelling and subcutaneous nodule in the left upper arm and on the back for 3 months. Blood examination showed eosinophila (21.2%), and anti-sparganum antibodies were positive. Skin biopsy of the lesion and histopathological examinations revealed dermal infiltrates of eosinophils but did not show any parasites. Thus, the patient was first diagnosed as sparganosis; however, new migratory swellings occurred after treatment with praziquantel for 3 days. On further inquiring, she recalled having eaten undercooked eels and specific antibodies to the larvae of Gnathostoma spinigerum were detected. The patient was definitely diagnosed as cutaneous gnathostomiasis caused by Gnathostoma sp. and treated with albendazole (1,000 mg/day) for 15 days, and the subsequent papule and blister developed after the treatment. After 1 month, laboratory findings indicated a reduced eosinophil count (3.3%). At her final follow-up 18 months later, the patient had no further symptoms and anti-Gnathostoma antibodies became negative. Conclusively, the present study is the first report on a human case of cutaneous gnathostomiasis in Henan Province, China, based on the past history (eating undercooked eels), clinical manifestations (migratory subcutaneous nodule and persistent eosinophilia), and a serological finding (positive for specific anti-Gnathostoma antibodies).

Keywords: Gnathostoma spinigerum, gnathostomiasis, migratory subcutaneous nodule, serodiagnosis, albendazole, China

INTRODUCTION

Gnathostomiasis is a food-borne parasitic zoonosis caused by the third stage larvae of the genus Gnathostoma. Human beings are an accidental and abnormal host for Gnathostoma. Human infection is mainly resulted from eating raw or undercooked intermediate hosts (e.g. fish, eels, and loaches) or paratenic hosts (e.g. crustaceans, freshwater fish, and mammals) containing the third-stage (L3) larvae [1]. The larvae cannot mature in humans and keep migrating in the skin, subcutaneous tissues, or other organs. Gnathostomiasis is characterized by intermittent creeping eruptions and/or migrating swellings and eosinophilia; larval migration to other tissues (visceral larva migrans) can result in a serious consequence [2]. If untreated, gnathostomiasis may remit and recur several times until death of the larvae up to 12 years after infection [3].

The endemic foci of gnathostomiasis have been predominantly distributed in Japan and Southeast Asia, particularly Thailand, but the disease is also endemic in Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Malaysia [4]. Human cases have also been reported in India, Australia, Brazil, and parts of South Africa, and it has been regarded as an emerging disease [5]. Imported human cases of gnathostomiasis were also reported in the Republic of Korea [6,7]. Recently, it has been known that this disease is endemic in the Pacific region of Mexico [8]. In China, gnathostomiasis occurred sporadically in 23 Provinces, Autonomous regions, or Municipalities. Until the year 2012, 57 cases of gnathostomiasis have been reported in the Chinese literatures [9]; however, only 1 case was reported in English [10]. Also, to our knowledge, no human cases of gnathostomiasis have been reported in Henan Province, China [11]. Accordingly, the present study reports for the first time a human case of cutaneous gnathostomiasis in Henan Province, China.

CASE RECORD

A 52-year-old lady from Zhengzhou city of Henan Province, central China, presented to the Parasitology Department of Zhengzhou University on 22 August 2011. She had a 3-month history of recurrent appearance of migratory reddish swelling in the upper arm and on the back. The initial lesions appeared on the left side of the back and subsequent lesions were observed in the left upper arm. These swellings were characterized by a migrating edema with a cord-like shape and pruritic nodules. The swellings reappeared in a different area close to the previous one after about 10-15 days of subsidence of the initial lesion. She was an officer, denied a history of travel abroad, and never had any pets, nor had a history of intimate exposure to stray cats, dogs, or other domestic animals. On physical examination, the migratory linear subcutaneous nodule was observed on the left side of her back.

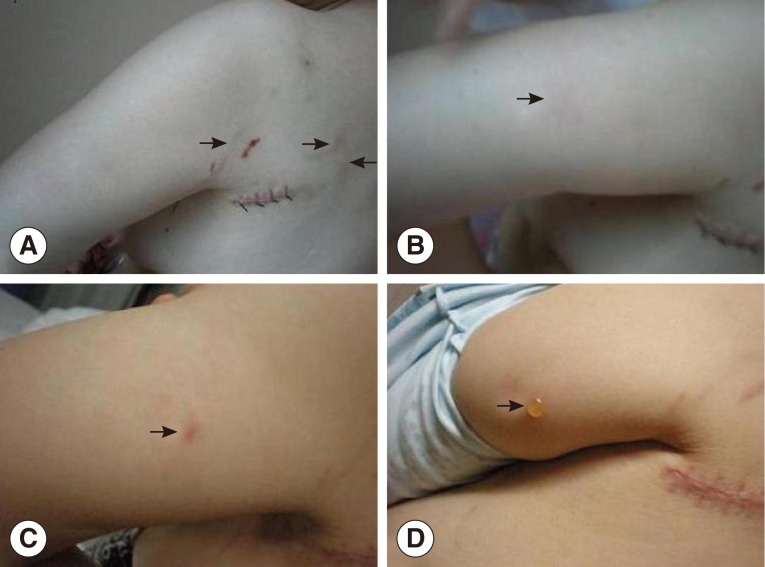

Initial laboratory testing revealed a normal white blood cell count of 4,900, but with high eosinophilia (21.2%, 1,040 eosinophils/ml). The chemistries, including liver function tests, were within normal limits. The serum specific antibodies against tissue-dwelling parasites (Paragonimus skrjabini, Schistosoma japonicum, metacestode of Taenia solium, and Trichinella spiralis) were assayed by ELISA or immunofluorescence test (IFT), and shown to be negative. However, anti-sparganum antibodies were positive by ELISA using excretory-secretory (ES) antigens of Spirometra erinacei spargana [12]. The optical density (OD) of the serum samples from this patient was 0.46, whereas the positive (patients with sparganosis) and negative (normal persons) controls were 0.55 and 0.21, respectively. A fecal examination was negative for parasites. Serum samples were sent to the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University and anti-sparganum antibodies were also positive. Skin biopsy was performed at 1 cm of the anterior end of the nodule near the axilla on the left side of the back on 28 August 2011. Worms were not observed during the operation. Histopathologic examination of the biopsy samples revealed a dense superficial and deep dermal infiltrate of eosinophils and neutrophils but did not show any parasites. One day after the skin biopsy, multiple migrating subcutaneous nodules reappeared on the patient's back (Fig. 1A). Subcutaneous sparganosis was diagnosed on the basis of clinical manifestations and results of serologic tests, and the patient was treated with praziquantel (75 mg/kg/day in 3 doses for 3 days) [13]. However, 1 day after the treatment, new migratory swellings occurred in the left upper arm (Fig. 1B); anti-sparganum antibodies were re-assayed and remained positive. On further inquiring, she recalled that she had eaten undercooked eels. Thus, gnathostomiasis was highly suspected on this history, together with symptoms such as recurrent migratory subcutaneous nodule and eosinophilia. The serum sample was sent to the Institute of Parasitic Diseases of Zhejiang Academy of Medical Sciences, dot immunogold filtration assay (DIGFA) using soluble antigens of the third stage larvae (L3) of G. spinigerum presented by Mahidol University in Thailand showed that anti-Gnathostoma antibodies were strongly positive, and anti-sparganum antibodies were only weakly positive.

Fig. 1.

Cutaneous gnathostomiasis in a 52-year-old woman from Henan Province, central China. (A) Multiple migrating subcutaneous nodules (arrows) on the back, occurring 1 day after skin biopsy. The suture wound is visible. (B) Migrating swellings (arrow) in the left upper arm, occurring 1 day after treatment with praziquantel (75 mg/kg/day in 3 doses for 3 days). (C) The subsequent papule (arrow) emerging 1 day after beginning of the treatment with albendazole (1,000 mg/day, twice daily). (D) The subsequent blister (arrow) developing on the 9th day of treatment with albendazole.

The patient was treated with albendazole (1,000 mg/day, twice daily for 15 days). One day after the beginning of the treatment, the migrating swellings in the left upper arm tended to be confined and a papule developed (Fig. 1C); subsequent blister emerged on the 9th day of treatment (Fig. 1D). However, parasites were not found by examination of the puncture samples of the blister. Two days after the treatment, the papule disappeared but anti-Gnathostoma antibodies were still positive; Laboratory testing revealed a white blood cell count of 5,800, with 5.5% eosinophils. After 1 month, laboratory findings showed an almost normal eosinophil count (3.3%). At her final follow-up at 18 months, the patient had no further symptoms and anti-Gnathostoma antibodies became negative.

DISCUSSION

Although 13 species of the genus Gnathostoma have been reported to date, 5 of them such as Gnathostoma spinigerum, G. nipponicum, G. hispidum, G. doloresi, and G. binucleatum infect humans [5,6]. Out of these species, G. binucleatum is a major etiologic agent of gnathostomiasis in endemic areas of America, especially in Mexico and Venezuela. G. spinigerum is the most common and important agent of gnathostomiasis in China. Out of 57 cases with gnathostomiasis reported in China during 1918-2012, 54 cases were caused by G. spinigerum, 2 by G. hispidum and 1 by G. doloresi [9]. A previous survey showed that 23 species of animals (6 cyclops, 13 fish, 2 frogs, and 1 each of snake and bird) served as the first or second intermediate host, or a paratenic host of G. spinigerum in 3 provinces (Jiangsu, Anhui, and Jiangxi) of China [14].

The triad of eosinophilia, migratory lesions, and obvious exposure risk are highly suggestive of the diagnosis of gnathostomiasis. The exposure risk usually include consumption of raw or undercooked fish (in particular, swamp eels and loaches), or meat of intermediate or paratenic hosts. The definite diagnosis was established by isolation of larvae from the lesions, but this is often difficult in migratory skin lesions. The detection rate of larvae in skin biopsy specimens was only 24-34% of the cases [15]. The skin biopsy in our patient reported failed to show the worms. Treatment with albendazole may promote outward migration of the larvae to the dermis, and stimulate development of a papule or pseudo-furuncle containing the larva. Biopsy of a papule or pseudo-furuncle subsequent to treatment increases the likelihood of demonstrating the larva on skin biopsy specimens [16]. Regrettably, our patient disagreed with a second skin biopsy. With introduction of antigens from L3 larvae of G. spinigerum, the serodiagnosis of gnathostomiasis became more convenient and efficient, although cross-reactivity with other parasitic infections remained a problem. Our patient was first misdiagnosed as sparganosis because of a cross-reactivity with in S. erinacei sparganun antigens. Tapchaisri et al. [17] found that a specific L3 antigen with a molecular mass of 24 kDa had the greatest specificity and reacted only with sera from the patients with gnathostomiasis sera and not with those from other parasitic infections. Hence, immunoblot is now regarded as the most valuable serologic test and can be used as a confirmatory test of gnathostomiasis when specific antibodies to 24 kDa component of G. spinigerum L3 larvae were detected. Although recommended dose of albendazole for gnathostomiasis is 400 mg/day for 21 days [18], our patient was cured with a shorter course of albendazole (1,000 mg/day for 15 days) treatment.

Although Gnathostoma larvae were not found in the skin biopsy of our patient, the patient was diagnosed as cutaneous gnathostomiasis according to the following evidences: the history of eating undercooked eels, typical clinical manifestations (recurrent migratory subcutaneous nodule), persistent eosinophilia, specific anti-Gnathostoma antibodies, and a cure by albendazole. The excellent therapeutic response to albendazole can differentiate it from sparganosis because albendazole has no obvious efficacy for treating sparganosis [19]. This case is most likely be caused by G. spinigerum which is the predominant agent of gnathostomiasis in China. Because clinicians outside of high endemic areas are unfamiliar with the disease, and therefore diagnosis is often missed or prolonged. The classic triad of intermittent migratory swellings, persistent eosinophilia, and a history of eating raw freshwater fish should alert physicians to the possible diagnosis of gnathostomiasis.

Recently, some Chinese people have the habit of eating raw fish; sashimi was often served in restaurants and hotels. In addition, some inhabitants like to eat quick-fried eels or scalded eel fillets. If the fillet was too large and the time of scalding was insufficient, the temperature in the fillet center would not be sufficient to kill the larvae. Recently, L3 of Gnathostoma spp. have also been detected from wild swamp eels sold at the market in Henan and Zhejiang Provinces (http://zjnews.zjol.com.cn/05zjnews/system/2011/10/28/017949925.shtml). In Thailand, the infection rate of farmed and wild eels with G. spinigerum was 10.2% and 20.4%, respectively [20]. Moreover, swallowing live loaches have become a folk remedy in some areas of China since some inhabitants believe the live loaches to have a medicinal role for treating diseases. Gnathostomiasis caused by swallowing live loaches was reported recently in Taiwan [21]. Gnathostomiasis cases resulted from ingestion of native loaches or loaches imported from Korea or mainland China were also reported in Japan [22]. Gnathostoma larvae were found in imported Chinese loaches in Korea [23]. To prevent human Gnathostoma infection, the government, public health officials, and medical practitioners should be aware of misdiagnosis of zoonotic gnathostomiasis. The best strategies for preventing gnathostomiasis are to educate people to only consume fully cooked meat, especially avoiding raw and undercooked freshwater fish and loaches in endemic areas.

In conclusion, we report here a case of cutaneous gnathostomiasis in Henan Province, China based on the history of eating undercooked eels, recurrent migratory subcutaneous nodule, persistent eosinophilia, specific anti-Gnathostoma antibodies, and cure by albendazole. Our study presents a risk of Gnathostoma infection by consumption of undercooked freshwater fish; therefore, fish inspection for Gnathostoma larvae should be carried out for ensuring food safety and public health.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Prof. Xiao Xian Gan, Institute of Parasitic Diseases of Zhejiang Academy of Medical Sciences, for her kindness in assaying the anti-Gnathostoma antibodies of our patient. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81172612)

References

- 1.John DT, Petri WA. Markell and Voge's Medical Parasitology. 9th ed. Missouri, USA: Elsevier; 2006. pp. 274–321. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finsterer J, Auer H. Parasitoses of the human central nervous system. J Helminthol. 2012 doi: 10.1017/S0022149X12000600. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X12000600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herman JS, Chiodini PL. Gnathostomiasis, another emerging imported disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:484–492. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00003-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vonghachack Y, Dekumyoy P, Yoonuan T, Sa-nguankiat S, Nuamtanong S, Thaenkham U, Phommasack B, Kobayashi J, Waikagul J. Sero-epidemiological survey of gnathostomiasis in Lao PDR. Parasitol Int. 2010;59:599–605. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vargas TJ, Kahler S, Dib C, Cavaliere MB, Jeunon-Sousa MA. Autochthonous gnathostomiasis, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:2087–2089. doi: 10.3201/eid1812.120367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim HS, Lee JJ, Joo M, Chang SH, Chi JG, Chai JY. Gnathostoma hispidum infection in a Korean man returning from China. Korean J Parasitol. 2010;48:259–261. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2010.48.3.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang JH, Kim M, Kim ES, Na BK, Yu SY, Kwak HW. Imported intraocular gnathostomiasis with subretinal tracks confirmed by western blot assay. Korean J Parasitol. 2012;50:73–78. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2012.50.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zambrano-Zaragoza JF, Durán-Avelar Mde J, Messina-Robles M, Vibanco-Pérez N. Characterization of the humoral immune response against Gnathostoma binucleatum in patients clinically diagnosed diagnosed with gnathostomiasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;86:988–992. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang LH, Xu LQ, Chen YD. Parasitic disease control and research in China. Beijing, China: Scientific and Technological Publishing House of Beijing; 2012. pp. 762–769. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li DM, Chen XR, Zhou JS, Xu ZB, Nawa Y, Dekumyoy P. Short report: case of gnathostomiasis in Beijing, China. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80:185–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang ZQ. The rare human helminthes in Henan province of China. Henan J Prev Med. 1996;7:44–47. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gan SB. Guideline of the clinical application of the anti-parasite drugs. Beijing, China: People's Health Publishing House; 2012. pp. 71–72. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cui J, Li N, Wang ZQ, Jiang P, Lin XM. Serodiagnosis of experimental sparganum infections of mice and human sparganosis by ELISA using ES antigens of Spirometra mansoni spargana. Parasitol Res. 2011;108:1551–1556. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-2206-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen QQ, Lin XM. A survey of epidemiology of Gnathostoma hispidum and experimental studies of its larvae in animals. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1991;22:611–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magaña M, Messina M, Bustamante F, Cazarín J. Gnathostomiasis: clinicopathologic study. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:91–95. doi: 10.1097/00000372-200404000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laga AC, Lezcano C, Ramos C, Costa H, Chian C, Salinas C, Salomon M, del Solar M, Bravo F. Cutaneous gnathostomiasis: report of 6 cases with emphasis on histopathological demonstration of the larva. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:301–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tapchaisri P, Nopparatana C, Chaicumpa W, Setasuban P. Specific antigen of Gnathostoma spinigerum for immunodiagnosis of human gnathostomiasis. Int J Parasitol. 1991;21:315–319. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(91)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kraivichian P, Kulkumthorn M, Yingyourd P, Akarabovorn P, Paireepai CC. Albendazole for the treatment of human gnathostomiasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1992;86:418–421. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(92)90248-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cui J, Wang MM, Zhao YW, Gan GH, Hu BW, Jiang P, Qi X, Liu LN, Wang ZQ. Efficacy of albendazole for treatment of mice infected with sparganum mansoni. Zhongguo Ji Sheng Chong Xue Yu Ji Sheng Chong Bing Za Zhi. 2012;30:71–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saksirisampant W, Thanomsub BW. Positivity and intensity of Gnathostoma spinigerum infective larvae in farmed and wild-caught swamp eels in Thailand. Korean J Parasitol. 2012;50:113–118. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2012.50.2.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuo YL, Wu YH, Su KE. Cutaneous larva migrans induced by swallowing live pond loaches. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:878–881. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2011.04116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nawa Y. Historical review and current status of gnathostomiasis in Asia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1991;22(suppl):217–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sohn WM, Kho WG, Lee SH. Larval Gnathostoma nipponicum found in the imported Chinese loaches. Korean J Parasitol. 1993;31:347–352. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1993.31.4.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]