Abstract

Background/Objectives

Calcipotriene is a topical vitamin D3 analogue approved for treatment of plaque and scalp psoriasis. We report the case of a 2-year-old boy whose atopic dermatitis(AD) flared in response to application of calcipotriene 0.005% cream and solution for mistaken diagnosis of plaque and scalp psoriasis. We investigated if the patient’s eruption was secondary to an allergic contact dermatitis. In the Stat6VT mouse model of AD, we tested if calcipotriene could induce the otherwise spontaneous AD-like phenotype.

Methods

Closed patch testing was done on the patient with calcipotriene solution and cream, Eucerin cream and 51% isopropanol. Stat6VT and wild type (WT) mice were treated for 7 days with calcipotriene solution or vehicle (isopropanol) applied to the right and left upper back skin, respectively, after which mice were followed longitudinally for ten weeks. Biopsies from prior treatment sites were then collected for histology and RNA isolation. RNA was analyzed for IL-4 expression using quantitative PCR.

Results

Patch testing was negative. Stat6VT mice, in contrast to WT mice, developed a persistent eczematous dermatitis at sites of calcipotriene application. Clinical and histologic features and elevated levels of IL-4 transcripts were consistent with the spontaneous AD-like phenotype seen in Stat6VT mice.

Conclusions

At sites of active disease, calcipotriene can worsen a flare of AD. In Stat6VT mice, calcipotriene can induce the AD-like phenotype.

Keywords: Atopic dermatitis, dermatitis-eczemas NOS, eczema, inflammatory disorders, therapy-topical

Introduction

Calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3) is a key ligand for the vitamin D receptor (VDR). Upon activation, by calcitriol, the VDR-specific transcriptional program modulates cellular proliferation and differentiation, calcium and phosphorus homeostasis and immune function1. Calcipotriene, an analogue of calcitriol, has proven efficacious in management in plaque and scalp psoriasis.

Development of atopic dermatitis (AD) involves T helper type 2 (Th2)-polarized immune responses and impaired epidermal barrier function2,3. Interleukin (IL)-4 is a cytokine produced by Th2 cells and other leukocytes and regulates aspects of immune function thought important for AD pathogenesis including Th2 cell development and class switching to IgE4. In keratinocytes, IL-4 signaling downregulates involucrin, loricrin and filaggrin transcripts and impairs epidermal barrier function5–7. Thus IL-4 appears to contribute to AD pathogenesis through its pro-inflammatory effects and its ability to compromise the epidermal barrier.

The Stat6VT transgenic mouse is a model of allergic lung and skin inflammation that develops an AD-like phenotype due to T cell-specific expression of a constitutively active mutant STAT6 (STAT6VT) resulting in Th2-polarized T cell development7,8. The AD-like lesions in Stat6VT mice are characterized clinically by an eczematous dermatitis and histologically by acanthosis, spongiosis and a dermal inflammatory infiltrate including lymphocytes and eosinophils. Transcripts for IL-4 are increased in lesional skin of Stat6VT mice, and IL-4-deficient Stat6VT mice do not to develop the AD-like phenotype, demonstrating a key role for IL-4 in this model7.

We report a case of AD that flared with application of calcipotriene cream and solution. Further, we investigated the effects of calcipotriene on induction of the AD-like phenotype in Stat6VT mice on the SKH1 background. Our findings reveal application of calcipotriene can induce the AD-phenotype in Stat6VT mice as defined by clinical and histologic parameters and increased expression of IL-4 transcripts.

Materials and Methods

Diagnosis, closed patch testing and clinical photographs of patient

Atopic dermatitis was diagnosed according the criteria of Hanifin and Rajka9. For patch testing, Finn Chambers (SmartPractice, Phoenix, AZ) containing Eucerin cream or 51% isopropanol solution (negative controls), calcipotriene solution and calcipotriene cream were applied to the back (nonlesional skin) of our patient. Patch test reading was performed at 72 and 120 hours. Parental Informed consent was obtained for photographs.

Stat6VT transgenic mice

Stat6VT mice on the C57BL/6 background have been described and were backcrossed to the SKH.1 background for 4 generations to generate Stat6VT.SKH1 mice7,8. Mice were maintained in a specific pathogen-free environment. Experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Treatment of mice with calcipotriene solution

Stat6VT and WT (SKH.1) mice were treated daily for seven days with 50 ul of calcipotriene solution (Vit D3) applied to the entire right upper back and 50 ul of vehicle (51% isopropanol; Cont) applied to the entire left upper back. After 7 days, treatment was discontinued and mice were monitored clinically for development of stable AD-like lesions. After 10 weeks, biopsies from treatment sites were collected for RNA and histology.

Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated using a Qiagen TissueLyser and Rneasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) followed by cDNA synthesis. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed using TaqMan primers and probes for IL-4 and GAPDH and a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). Relative expression of IL-4 was determined using the −ΔΔCT method with GAPDH as the endogenous reference.

Histology

Biopsy specimens were collected in 10% buffered formalin and transferred to 70% ethanol. Paraffin-embedding, sectioning and staining were performed by the Department of Pathology at Indiana University.

Statistics

Data are expressed as standard error of the mean. Statistical significance was evaluated using a two-tailed Student’s t-test with a P value of less than 0.05 considered significant.

Results

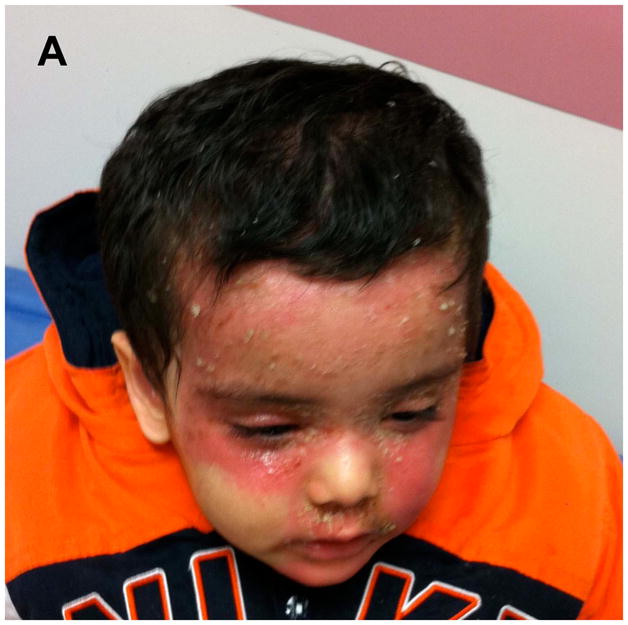

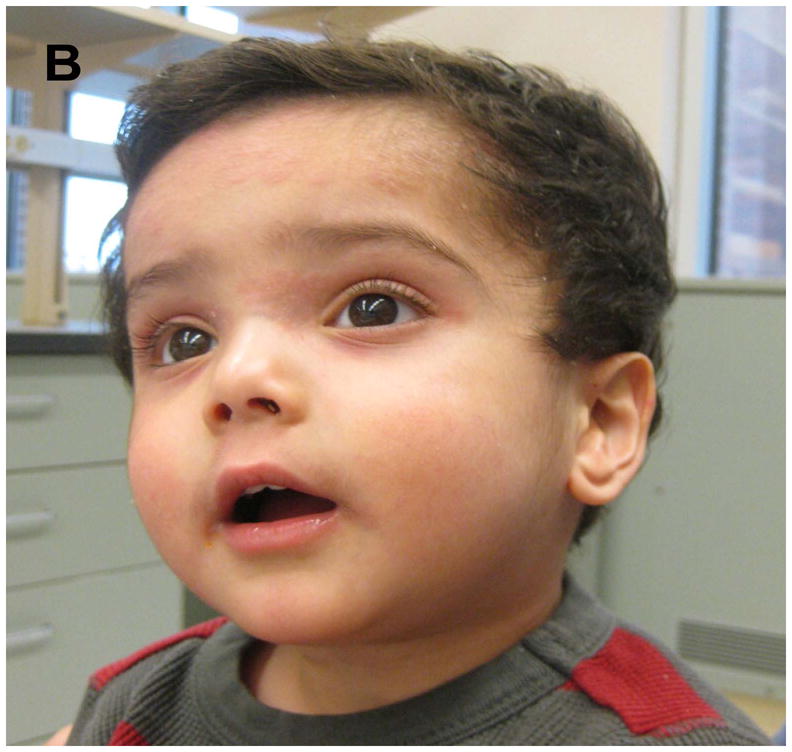

A 2-year-old Indian male with documented AD, an elevated total serum IgE (3164 kU/L) presented with a severe flare of an eczematous dermatitis on the scalp and face. The flare began within 24 hours of applying calcipotriene 0.005% cream and solution to sites of AD due to mistaken diagnosis of psoriasis. The flare was limited to sites of calcipotriene application, progressed over 5 days of calcipotriene use (Figure 1A) and markedly improved within 72 hours of discontinuing calcipotriene and applying low potency topical corticosteroids (Figure 1B). Closed patch testing with calcipotriene solution and cream, Eucerin cream and 51% isopropanol solution was negative at 72 and 120 hours. These findings suggest topical application of a vitamin D analogue can exacerbate a flare of AD.

Figure 1.

Flare of AD following application of calcipotriene. (A) Photographs of patient’s AD flare after five days of applying calcipotriene and (B) following discontinuation of calcipotriene and treatment with topical corticosteroids.

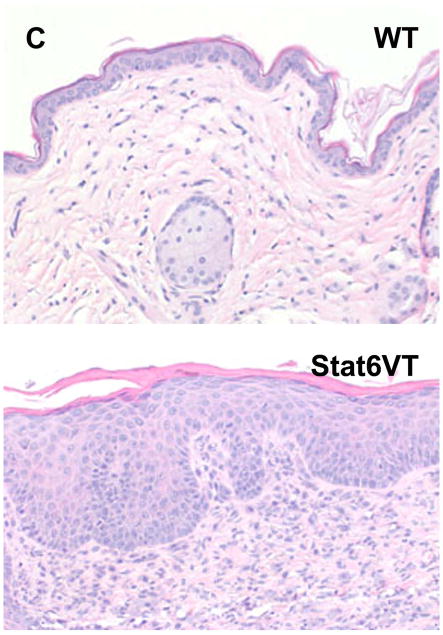

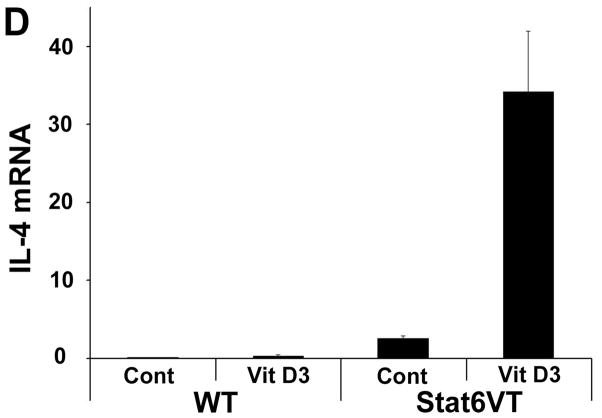

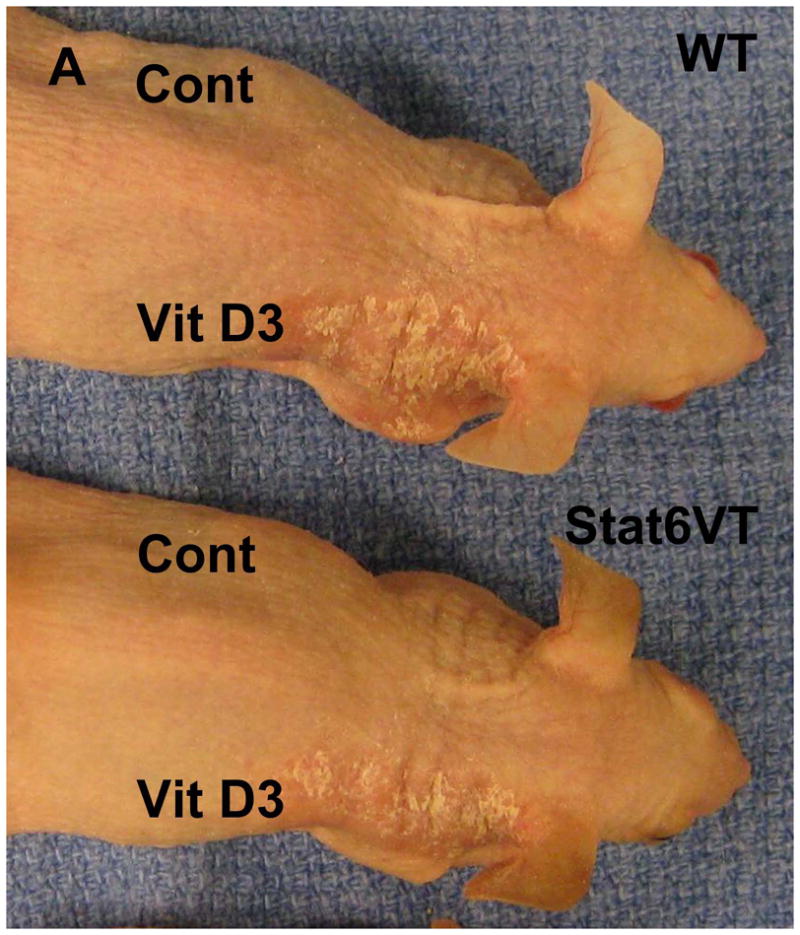

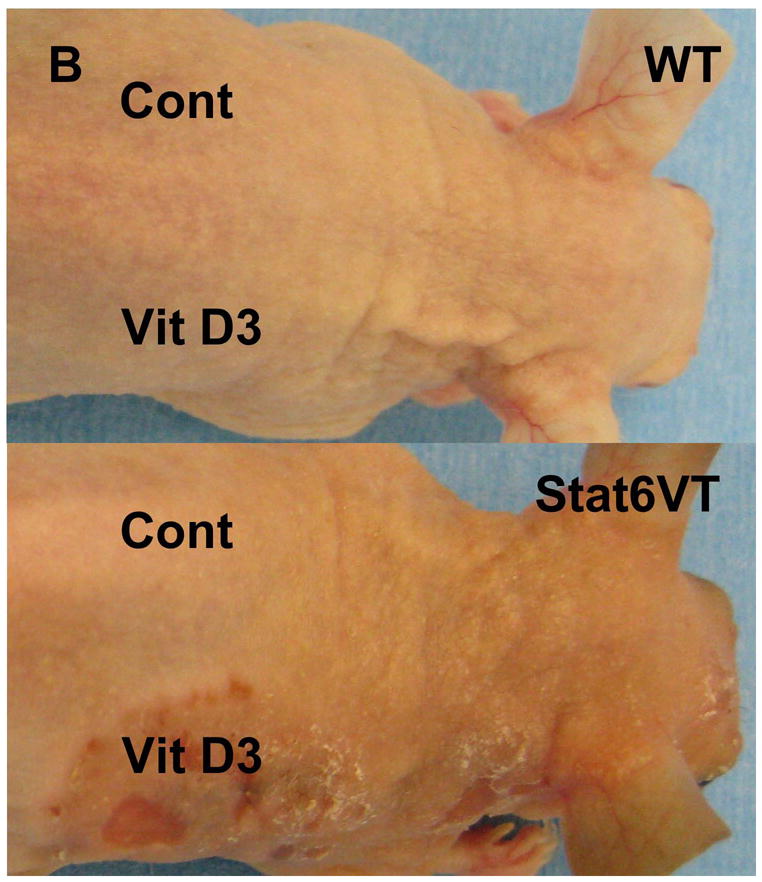

Based on these observations, we investigated the effect of calcipotriene on Stat6VT mice7,8. Stat6VT and WT mice were treated with calcipotriene solution and isopropanol vehicle as detailed in the Materials and Methods. As shown in Figure 2A, all mice (WT, top panel; Stat6VT, bottom panel) developed an eczematous dermatitis at sites of calcipotriene (Vit D3)application but not on the vehicle-treated skin (Cont). This eruption resolved in WT mice within one week of discontinuing calcipotriene (Figure 2B, top panel). In contrast, in Stat6VT mice, the eruption persisted for 10 weeks (Figure 2B, bottom panel), at which time skin was collected from all mice for histology and PCR.

Figure 2.

Effect of calcipotriene on WT and Stat6VT mice. (A) Transient calcipotriene-induced dermatitis (Vit D3) on WT and Stat6VT mice versus normal-appearing vehicle-treated skin(Cont). (B) Persistent dermatitis in Stat6VT mice at sites of previous treatment with calcipotriene(Vit D3) that is not seen with vehicle (Cont) nor in WT mouse skin previously treated with calcipotriene or vehicle. (C) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of dermatitis shown in (B). Bottom panel demonstrates persistent dermatitis in Stat6VT mice contrasted with WT skin previously treated with calcipotriene shown in the top panel (20x). (D) Increased IL-4 mRNA in persistent dermatitis of Stat6VT mice relative to vehicle-treated Stat6VT skin and skin from WT mice previously treated with calcipotriene or vehicle (expressed as relative units normalized to GAPDH). The asterisk denotes a statistically significant difference (p <0.01) compared to WT and vehicle-treated controls.

In contrast to vehicle-treated skin and non-lesional skin from Stat6VT mice, histologic analysis of the persistent eczematous dermatitis from Stat6VT mice revealed parakeratosis, acanthosis, spongiosis and a moderately dense perivascular and interstitial lymphocyte-predominant infiltrate (Figure 2C, bottom panel). These findings are consistent with AD-like lesions in Stat6VT mice7.

To validate the clinical and histologic findings suggesting calcipotriene can induce AD-like lesions in Stat6VT mice, IL-4 and IL-13 transcripts were measured with qPCR. While no significant difference in IL-13 expression was detected (unpublished observations), IL-4 expression was significantly higher (P<0.01) in calcipotriene-induced (Vit D3) lesional skin of Stat6VT mice compared to non-lesional vehicle-treated skin (Cont) and WT control skin previously treated with vehicle or calcipotriene (Figure 2D).

Discussion

While the therapeutic benefit of topical vitamin D analogues in the treatment of plaque and scalp psoriasis is clear, their mechanism of action in psoriasis and other dermatoses is not. Multiple studies in the literature demonstrate topical application of the 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 analogue or the active drug in calcipotriene, MC903, induce an AD-like eruption in mice, and elegant studies show this is a VDR- and thymic stromal lymphopoietin-dependent process, rather than a simple irritant contact dermatitis10,11. Calcipotriene appeared to worsen our patient’s AD, but with patch testing, did not seem to affect his nonlesional skin. While this could suggest an alterative explanation for exacerbation of his AD flare (e.g. cessation of topical steroids), calcipotriene’s apparent differential effect on lesional versus nonlesional skin may be explained by differences in barrier function.

The role of vitamin D in AD appears complex given its effects on skin barrier function and immunity and the apparent discordant effects of systemic versus topical Vitamin D administration1,10,11. Vitamin D insufficiency is associated with AD, and oral supplementation improved global skin scores in a randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled trial of patients with AD12. In contrast, our findings and previous investigations in mouse models suggest AD is exacerbated by topical application of a vitamin D3 analogue10,11. It is unclear how to reconcile these disparities, and the pathophysiologic correlate of topical application of vitamin D remains to be defined. It is possible that the disparate effects of topical versus systemic vitamin D result from differences in target cell populations. For example, systemically administered1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 can promote tolerogenic dendritic and regulatory T celldevelopment13,14, which could explain the reported beneficial effect of oral vitamin D supplementation on AD. However, stimulation of keratinocytes (and dendritic cells) by topical application may override the immunosuppressive effects of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, thus promoting a pro-allergic milieu. The same mechanism might contribute to the therapeutic benefit of vitamin D analogues for psoriasis via IL-4-mediated interference with the IL-23/IL-17 axis.

In summary, our clinical findings suggest calcipotriene can exacerbate a flare of AD. Moreover, we describe an experimental system to further dissect the molecular mechanisms by which topically applied 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 analogues can induce the AD-like phenotype in Stat6VT mice7. Studies are ongoing to better understand the pathogenic mechanisms of lesion development and persistence in this model.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Physician-Scientist Career Development Award from the Dermatology foundation (MJT), NIH grant U19 AI070448 (MHK & JBT) and R01 AI095282 (MHK).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflict of interest

References

- 1.Searing DA, Leung DYM. Vitamin D in Atopic Dermatitis, Asthma and Allergic Diseases. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2010;30:397–409. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bieber T. Atopic Dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1483–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra074081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sehra S, Tuana FM, Holbreich M, et al. Scratching the surface: towards understanding the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. Crit Rev Immunol. 2008;28:15–43. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v28.i1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carmi-Levy I, Homey B, Soumelis V. A Modular View of Cytokine Networks in Atopic Dermatitis. Clinic Rev Allerg Immunol. 2011;41:245–253. doi: 10.1007/s12016-010-8239-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howell MD, Kim BE, Gao P, Grant AV, Boguniewicz M, DeBenedetto A, Schneider L, Beck LA, Barnes KC, Leung DY. Cytokine modulation of atopic dermatitis filaggrin skin expression. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:R7–R12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim BE, Leung DY, Boguniewicz M, Howell MD. Loricrin and involucrin expression is down-regulated by Th2 cytokines through STAT-6. Clin Immunol. 2008;126:332–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sehra S, Yao Y, Howell MD, Nguyen ET, et al. IL-4 Regulates Skin Homeostasis and the Predisposition toward Allergic Skin Inflammation. J Immunol. 2010;184:3186–3190. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruns HA, Schindler U, Kaplan MH. Expression of a constitutively active Stat6 in vivo alters lymphocyte homeostasis with distinct effects in T and B cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:3478–87. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh) 1980;92:44–7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li M, Hener P, Zhang Z, et al. Topical vitamin D3 and low-calcemic analogs induce thymic stromal lymphopoietin in mouse keratinocytes and trigger an atopic dermatitis. PNAS. 2006;103:11736–11741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604575103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li M, Hener P, Zhang Z, et al. Induction of Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin Expression in Keratinocytes Is Necessary for Generating an Atopic Dermatitis upon Application of the Active Vitamin D3 Analogue MC903 on Mouse Skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:498–502. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sidbury R, Sullivan AF, Thadhani RI, et al. Randomized controlled trial of vitamin D supplementation for winter-related atopic dermatitis in Boston: a pilot study. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:245–7.11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gregori S, Casorati M, Amuchastegui S, et al. Regulatory T cells induced by 1a,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and mycophenolate mofetil treatment mediate transplantation tolerance. J Immunol. 2011;167:1945–1953. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takeda M, Yamashita T, Sasaki N, et al. Oral administration of an active form of vitamin D3 (calcitriol) decreases atherosclerosis in mice by inducing regulatory T cells and immature dendritic cells with tolerogenic functions. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:2495–503. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.215459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]