Abstract

Introduction

There is evidence from around Europe of the availability and use of 6-(2-aminopropyl)benzofuran (6-APB) as a recreational drug. However, there is currently limited information on the acute toxicity of this compound. We describe here a case of acute toxicity associated with recreational use of legal high (6-APB) and cannabis, in which the comprehensive toxicological analysis confirmed the presence of a significant amount of 6-APB together with metabolites of both tetrahydrocannabinol and the synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonist (JWH-122).

Case Report

A 21-year-old gentleman with no previous medical and psychiatric history was brought to the emergency department (ED) after he had developed agitation and paranoid behaviour following the use of 6-APB purchased over the Internet. There was no obvious medical cause for his acute psychosis. He required diazepam to control his agitation and was subsequently transferred to a psychiatric hospital for ongoing management of his psychosis. Toxicological screening of a urine sample collected after presentation to the ED detected 6-APB, with an estimated urinary concentration of 2,000 ng/ml; other drugs were also detected, but at lower concentrations including metabolites of the synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonist JWH-122 and tetrahydrocannabinol.

Conclusion

This is the first case of analytically confirmed acute toxicity associated with the detection of 6-APB which will provide some information on acute toxicity of this drug to help clinicians with the management of such patients and legislative authorities in their consideration for the need of its control.

Keywords: Benzofuran, 6-APB, 6-(2-Aminopropyl)benzofuran, Legal high, Toxicity, Benzo Fury

Introduction

There has been increasing availability and use of a range of novel psychoactive substances (NPS, commonly known as ‘legal highs’) in the UK and Continental Europe, North America and elsewhere in the world over the last few years [1]. Often, there is limited information available on the pharmacology and toxicology of these drugs, and triangulation of data from a variety of sources is necessary to describe the risks associated with their use [2]. One of the key components of this data triangulation is case reports of acute toxicity with confirmation of the NPS in biological samples.

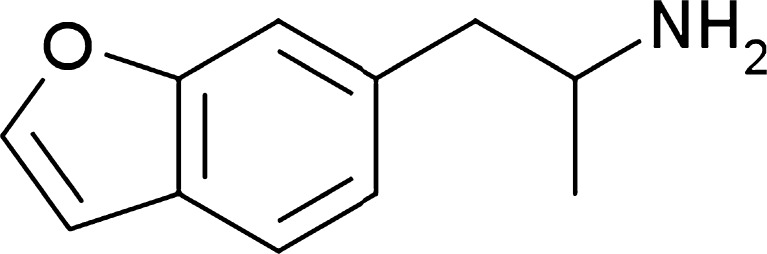

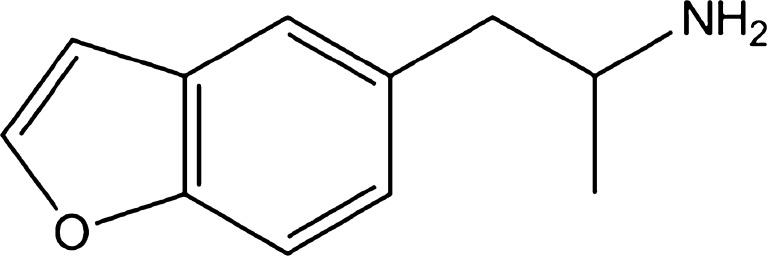

One class of NPS that has emerged is the benzofurans, including 5-(2-aminopropyl)benzofuran (5-APB) and 6-(2-aminopropyl)benzofuran (6-APB) (Figs. 1 and 2) [3]. 5-APB and 6-APB are benzofuran analogues of 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA) that were originally synthesised in 1993 [4]. They have been reported in seized samples in the UK and elsewhere in Europe since 2010, and more recently, 5-APB has been detected in pooled urine samples in both city centre and festival urine collections confirming its use in the UK [5–7]

Fig. 1.

Chemical Structure of 6-APB

Fig. 2.

Chemical Structure of 5-APB

Recent studies have shown that 6-APB is a triple monoamine reuptake inhibitor and a potent agonist for the 5HT2B and 5HT2C receptors [8]. There are, however, no published data on the acute toxicity related to cases of analytically confirmed use of 6-APB. We describe here the first case of acute toxicity associated with recreational use of legal high (6-APB) and cannabis, in which the urinary analysis confirmed the presence of a significant amount of 6-APB together with other metabolites of the synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonist JWH-122 and tetrahydrocannabinol.

Case Report

A 21-year-old gentleman with no previous medical or psychiatric history was brought to the emergency department (ED) by his friends as he developed agitation and paranoid thoughts and started cutting his forearms with a razor blade. He admitted to have ingested 0.4 g of 6-APB and smoking cannabis over a 2-day period. He was unable to recall the exact time of use of these drugs but could remember that he last took them on the day of admission. He stated that he had bought 6-APB from an Internet supplier and that this was the first time that he had experimented with 6-APB. He had been using cannabis regularly over the weekend for the last 2 to 3 years but did not report any previous complications related to his use of cannabis.

On arrival in the ED, he was noted to be agitated and insisted that one of his friends whom he had not met for a long while might be dead. He also complained that everyone in the ED was ‘trying to read his mind’ and were ‘looking at him in a funny way’. He became more agitated when he was asked to recall the incidents that led to his presentation and was unable to remember much detail, except having taken 6-APB. He had sustained multiple lacerations over both his forearms. He had a normal temperature (36.5 °C), heart rate (84 beats per min) and blood pressure (120/64 mmHg). The rest of his physical examination was unremarkable; in particular, there were no clinical features of serotonin toxicity (nystagmus, hypertonia, hyper-reflexia and clonus) on neurological examination.

Arterial blood gas analysis performed on room air (21 % oxygen) revealed no acid–base disturbance (pH 7.359, pCO2 5.98 kPa, pO2 10.78 kPa, bicarbonate 24.6 mmol/l, base excess −1.1 mmol/l), and further blood tests including renal and liver function tests, creatine kinase, full blood count and coagulation profile were normal.

He was seen by the clinical toxicologists, the plastic surgeons and the psychiatrists and was admitted to the emergency medical unit (observation ward). The working diagnosis at the time of presentation was drug-induced psychosis associated with self-harm.

He underwent a washout and repair of the lacerated tendons (palmaris longus and flexor carpi radialis tendon) of his left forearm and closure of the multiple forearm lacerations. His agitation and psychotic features worsened on the second day of his admission when he verbalised that he ‘might have killed someone’ and that he ‘might be a terrorist’. He exhibited suicidal ideation when interviewed by a psychiatrist. He was found to be fluctuating between agitation and paranoia, to experiencing low mood and delusional thoughts throughout his 5-day stay in the hospital. He did not exhibit any signs of autonomic hyperactivity (e.g. sweating, hand tremors, tachycardia or seizures). He was not a chronic alcohol, benzodiazepine or sedative user, and therefore, it was unlikely that the deterioration of his mental state was due to a withdrawal state from alcohol and/or benzodiazepines. He required diazepam (4 to 10 mg daily) to control his symptoms and was placed under the Section 2 of the Mental Health Act 1983 (2007) [9]. He was subsequently transferred to a psychiatric hospital for further treatment of his psychotic symptoms. In the psychiatric hospital, his condition improved with no further display of psychotic features, and the Mental Health Act section was rescinded. He was discharged after 3 days with plans to return to his native country with his parents for further psychiatric monitoring to ensure that there was no recurrence of his psychotic symptoms.

Toxicological Screening

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for toxicological analysis of his urine sample collected at the time of presentation to the ED. The urine sample was initially pretreated with β-glucuronidase to cleave any glucuronic acid conjugates and was then prepared for analysis using solid-phase extraction sample preparation techniques. The resulting prepared sample was then analysed using a high-performance liquid chromatography interfaced to high-resolution accurate mass spectrometry operating in full-scan mode.

6-APB was detected in the urine, with an estimated urinary concentration of 2,000 ng/ml. In addition, metabolites of the synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonist JWH-122 and the 11-nor-9-carboxy-delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol metabolite of tetrahydrocannabinol were detected. Oxazepam (20 ng/ml) and nordiazepam (150 ng/ml) detected are likely to reflect diazepam administered in the ED prior to the collection of the urine sample. Screening also detected 6-(2-methylaminopropane)benzofuran (30 ng/ml), amphetamine (90 ng/ml), chloroquine (5 ng/ml), ketamine metabolites (3 ng/ml) and ephedrine (800 ng/ml).

Discussion

We report here a patient with drug-induced psychosis and agitation with deliberate self-harm after oral consumption of 6-APB and smoking cannabis. This is the first case of acute toxicity related to analytically confirmed 6-APB use in adults. Other psychoactive substances were also detected, and so, it is not possible to be certain to what extent all of the features described were due to 6-APB; there is a potential that cannabis and/or the synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists also detected may have played a role.

6-APB is one of a number of benzofurans that has emerged as a recreational drug since 2010 [1]. 6-APB is a structural analogue of MDA where the methylenedioxy ring has been replaced with a benzofuran ring, and this places 6-APB in the amphetamine class of phenethylamines [10, 11]. It is available from a number of ‘legal high’ websites and is sold both in tablet and powder form in quantities ranging from 100 mg to 100 g [12–14]. 6-APB is sold both under its own name, under other names such as Benzo Fury and as a ‘research chemical that is not meant for human consumption’. However, analysis of Benzo Fury products has shown that these can contain a variety of different NPS; in one study, the Benzo Fury product was found to contain caffeine, 1-benzylpiperazine and 3-trifluoromethylphenylpiperazine with no benzofurans or benzodifurans [15].

There are limited data available on the prevalence of use of the 6-APB and other benzofurans as they are not included in population surveys of drugs use, and only one sub-population survey has included the benzofurans and/or related benzodifurans. In the 2012 Global Mixmag/Guardian Drugs Survey, 3.2 % of UK respondents indicated lifetime use of ‘Benzo Fury’ (2.4 % in the previous 12 months) [16]. Less than 0.5 % of US respondents reported Benzo Fury use in the previous 12 months [16]. The survey did not ask about the use of 5-APB, Bromo-DragonFLY or 2C-B-FLY [16]. 5-APB has been detected in the analysis of samples from portable urinals in both city centres and music festivals confirming use of benzofurans in the UK [5–7]. There are reports of 5-APB and 6-APB use on Internet discussion forums from the late 2010 [17–20]. Users report nasal insufflation of powder, ingestion of powder (these reports include direct ingestion of powder, powder dissolved in a liquid and powder wrapped in tissue paper) and rectal administration [17–20].

Recent in vitro human receptor binding assay studies using the US National Institute of Mental Health Psychoactive Drug Screening Program have shown that 6-APB is a triple monoamine reuptake inhibitor and a potent agonist for the 5HT2B and 5HT2C receptors [8]. The agonism for 5HT2B could result in cardiotoxicity with long-term use of 6-APB, similar to side effects seen in chronic use of fenfluramine and 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine (MDMA) [8], and its action on 5HT2C receptors would result in appetite suppression [11].

However, there are limited data available on the acute toxicity associated with 6-APB use. There has been report in the UK media of a death in the UK potentially linked to Benzo Fury use; however, this report has not been substantiated, and we are not aware of analytical findings in this case [21]. 6-APB is not a controlled drug under the UK Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 and is marketed to users as a legal high with its purported desirable pharmacological effects such as mood-enhancing and stimulant properties [10, 22].

There are reports from nine 6-APB users on Erowid, who report palpitations, hot flushes, headache, paranoia, anxiety and visual and auditory hallucinations; seven report lone 6-APB use, and two report use of 6-APB in combination with cannabis and 4-hydroxy-N-methyl-N-ethyltryptamine and 2-ethyl-2,5,dimethoxyphemethylamine [17, 18]. Some users also report an unpleasant ‘comedown’ from 6-APB lasting for a few days [17–19]. Other users report that 6-APB creates a similar desired effect to MDMA but is associated with a feeling of anxiety that can last up to 5 days after use [17–20].

These anecdotal data from Internet discussion forums, taken together with our case, confirm the potential for significant acute toxicity including severe and prolonged neuropsychiatric symptoms (acute psychosis and agitation leading to self-harm) associated with 6-APB use. We feel that consideration should be given to the control of 6-APB and related benzofurans. It is also important that emergency physicians and clinical toxicologists managing patients with benzofuran use consider an extended period of observation if neuropsychiatric features are present.

References

- 1.European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (2012) The state of the drugs problem in Europe. http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/attachements.cfm/att_190854_EN_TDAC12001ENC_.pdf. Accessed 30 Apr 2013

- 2.Wood DM, Dargan PI. Understanding how data triangulation identifies acute toxicity of novel psychoactive drugs. J Med Toxicol. 2012;8:300–303. doi: 10.1007/s13181-012-0241-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mustafa A. The benzofurans—chemistry of heterocyclic compounds: a series of monographs. 29. New York: Wiley; 1974. pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monte AP, Marona-Lewicka D, Cozzi NV, Nichols DE. Synthesis and pharmacological examination of benzofuran, indan, and tetralin analogues of 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine. J Med Chem. 1993;36:3700–3706. doi: 10.1021/jm00075a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (2011) Consideration of the novel psychoactive substances (‘legal highs’). http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/publications/agencies-public-bodies/acmd1/acmdnps2011?view=Binary. Accessed 30 Apr 2013

- 6.Archer JR, Dargan PI, Chan WL, Hudson S, Wood DM (2013) Variability in recreational drugs and novel psychoactive substances detected in anonymous pooled urine samples from street pissoirs (street urinals) over time: a technique to monitor trends in drugs use. Clin Tox (Phila) (in press)

- 7.Wood DM, Archer JR, Measham F, Hudson S, Dargan PI (2013) Detection of use of novel psychoactive substances by attendees at a music festival in the North West of England. Clin Tox (Phila) (in press)

- 8.Iversen L, Gibbons S, Treble R, Setola V, Huang XP, Roth BL. Neurochemical profiles of some novel psychoactive substances. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;700:147–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mental Health Act (1983) 2007. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2007/12/pdfs/ukpga_20070012_en.pdf. Accessed 30 Apr 2013

- 10.ToxBase (2013) Benzo Fury. http://www.toxbase.org/Poisons-Index-A-Z/6-Products/6-APB/. Accessed 30 Apr 2013

- 11.Briner K, Burkhart JP, Burkholder TP, Fisher MJ, Gritton WH, Kohlman DT, Liang SX, Miller SC, Mullaney JT, XU Y-C, XU Y (2006) Aminoalkylbenzofurans as serotonin (5-HT(2c)) agonists. United States Patent US 7045545 B1. http://worldwide.espacenet.com/publicationDetails/biblio?CC=US&NR=7045545B1&KC=B1&FT=D&date=20060516&DB=&&locale=en_EP. Accessed 30 Apr 2013

- 12.Buy Research Chemicals UK (2013) 6-APB Pellets. https://www.buyresearchchemicals.co.uk/buy-6-apb/6-apb-pellets.html. Accessed 30 Apr 2013

- 13.Purechemicals.net (2013) Buy 6-APB powder. http://www.purechemicals.net/buy-6-apb-powder-71-c.asp. Accessed 30 Apr 2013

- 14.Official Benzo Fury™ (2013) Benzo Fury Pellets. http://www.officialbenzofury.com/products/Benzo-Fury-Pellets.html. Accessed 30 Apr 2013

- 15.Baron M, Elie M, Elie L. An analysis of legal highs: do they contain what it says on the tin? Drug Testing Analysis. 2011;3:576–581. doi: 10.1002/dta.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Global Drug Survey (2013) 2012 Global Drug Survey. http://globaldrugsurvey.com/run-my-survey/2012-global-drug-survey. Accessed 30 Apr 2013

- 17.Erowid (2013) Erowid experience vaults: 5-APB reports (also 5-(2-aminopropyl)benzofuran, 1-(1-benzofuran-5-yl)propan-2-amine). http://www.erowid.org/experiences/subs/exp_5APB.shtml. Accessed 30 Apr 2013

- 18.Erowid (2013) Erowid experience vaults: 6-APB reports (also 6-(2-aminopropyl)benzofuran, Benzo Fury). http://www.erowid.org/experiences/subs/exp_6APB.shtml. Accessed 30 Apr 2013

- 19.Blue Light (2013) Forum: 6-APB report from an ickle noob. http://www.bluelight.ru/vb/threads/525471-6-APB-report-from-an-ickle-noob. Accessed 30 Apr 2013

- 20.Drugs Forum: 6-APB. http://www.drugs-forum.com/forum/showwiki.php?title=6-APB. Accessed 30 Apr 2013

- 21.BBC News Jersey (2012) Matthew Wing inquest: legal high caused Jersey man’s death (17th October 2012). http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-jersey-19964309. Accessed 30 Apr 2013

- 22.FRANK (2013) Talk to Frank: APB (related terms: White Pearl, Benzo Fury, 6-APDB, 6-APB, 5-APDB, 5-APB). http://www.talktofrank.com/drug/apb. Accessed 30 Apr 2013