ABSTRACT

The Correlates of Indoor Tanning in Youth (CITY100) project evaluated individual, built-environmental, and policy correlates of indoor tanning by adolescents in the 100 most populous US cities. After CITY100's completion, the research team obtained supplemental dissemination funding to strategically share data with stakeholders. The primary CITY100 dissemination message was to encourage state-level banning of indoor tanning among youth. We created a user-friendly website to broadly share the most relevant CITY100 data. Journalists were a primary target audience, as were health organizations that would be well positioned to advocate for legislative change. CITY100 data were used to pass the first US state law to ban indoor tanning among those under 18 (CA, USA), as well as in other legislative advocacy activities. This paper concludes with lessons learned from CITY100 dissemination activities that we hope will encourage more health researchers to proactively address policy implications of their data and to design relevant, effective dissemination strategies.

KEYWORDS: Indoor tanning, Youth, Policy, Dissemination

Indoor tanning is a risk factor for melanoma [1–3] and is used frequently by adolescent girls [4]. The Correlates of Indoor Tanning in Youth (CITY100) project was a National Cancer Institute (NCI)-funded study that evaluated individual-, built-environmental-, and policy-level [5] correlates of indoor tanning by adolescents (N = 6,125) in the 100 most populous US cities [6]. CITY100 involved several interlocking studies. The central CITY100 study component was a telephone survey conducted January–December of 2005 among adolescent–parent pairs to measure prevalence and psychosocial correlates of adolescent indoor tanning use in the past 12 months. CITY100 also provided a “report card” of existing laws for protecting youth [7], documented prevalence of indoor tanning salons in each of the included cities [8], and evaluated 3,647 of those indoor tanning salons' compliance with state laws and the Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) recommendations by having data collectors pose as prospective 15-year-old clients to briefly assess practices [9]. These environmental- and policy-level factors (i.e., indoor tanning laws, indoor tanning facility availability, and tanning facility compliance) were evaluated as adolescent indoor tanning use correlates.

Several multilevel correlates of indoor tanning behavior were identified in CITY100, including increased rates of tanning among adolescents with a parent who reported indoor tanning behavior and among those living closer to an indoor tanning facility [6]. Importantly, our study found no significant association with adolescent indoor tanning behavior based on presence of state indoor tanning laws (e.g., parental consent and parental accompaniment), suggesting that current laws are not working to prevent adolescent indoor tanning behavior. Given the high potential of policy change for broad public health reach and impact, the primary recommendation from CITY100 findings was to ban indoor tanning among youth, in line with World Health Organization recommendations [10] and legislation passed in other countries (e.g., Australia) [11]. Our research team obtained a competitive NCI supplemental dissemination grant to work with a media specialist, partner with relevant health organizations, and strategically share data with stakeholders to disseminate key findings from CITY100. This paper describes those dissemination processes and outcomes and discusses implications for impacting community health via legislative advocacy approaches to communicating scientific findings.

DISSEMINATION APPROACH

CITY100 dissemination efforts were guided by several relevant theoretical perspectives. We drew on the public health advocacy framework, which provides a practical model to guide staffing decisions for public health advocacy activities, along with an overview of the processes involved [12]. The model specifies three sequential stages, likened to “an assembly line”: the information stage involves identification and quantification of a public health problem (carried out with the main CITY100 study [6–9, 13, 14]; the strategy stage consists of “using the available information to identify what needs to change to improve public health” (p. 723), which would include mobilizing coalitions, disseminating relevant data and messages to key audiences, creating fact sheets, and generating news stories about the problem and potential solutions; and the action stage, which includes (but is not limited to) convincing policymakers to get involved and craft legislation. The latter two stages were emphasized during the CITY100 dissemination phase.

The constructs of “issue attention,” “public attention,” and “attention cycles” [15–17] also guided the CITY100 dissemination efforts. Downs [16] proposed a five-stage issue attention cycle: (1) preproblem stage, in which an undesirable condition has not yet captured widespread public attention; (2) alarmed discovery and euphoric enthusiasm, in which the public becomes acutely aware of a problem and optimistic about society's capacity to solve it; (3) realizing the cost of solving the problem; (4) gradual decline of intense public interest due to discouragement and/or boredom; and (5) the postproblem stage, whereby “public concern moves into a prolonged limbo” but may be reactivated. Public attention about issues can recycle based on many factors. Public attention considerations were critical in our efforts because, as pointed out by Newig [17], “we conceive public attention as a social phenomenon that influences political action and that is also affected by it” (p. 154). Simply put, unless there is some adequate level of public attention directed to indoor tanning issues, policymakers are not likely to pass new legislation or strengthen existing legislation.

Dissemination messages

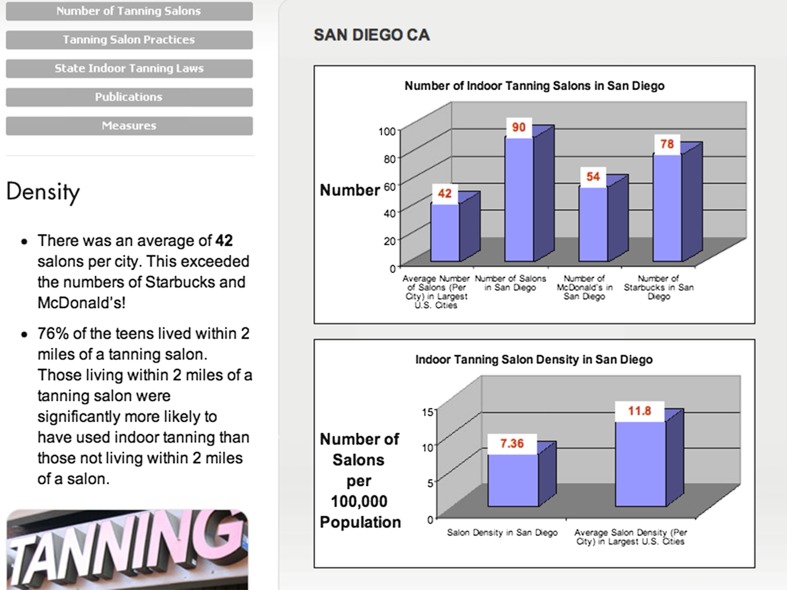

Several key CITY100 findings were identified and communicated to target audiences: (1) there is a high prevalence of indoor tanning salons in US cities, with higher numbers of salons than both Starbucks and McDonald's [8]; (2) tanning salons allow teens to tan daily, contrary to FDA recommendations [9]; and (3) parental consent laws are not decreasing indoor tanning among teens [6]. Based on these findings, the primary dissemination message was a recommendation for states to ban indoor tanning for minors. Prioritized findings for communication were identified based on public health relevance while also considering what messages would be most salient and motivating for target audiences. The study name also was changed to “Controlling Indoor Tanning among Youth” to more accurately reflect the purpose of study activities during the dissemination phase.

Dissemination strategies

Figure 1 depicts the target audiences of CITY100 dissemination efforts. Because the mass media act as catalysts and amplify public attention [17], journalists were targeted heavily in dissemination activities. We also prioritized partnership with health organizations that would be well positioned to advocate for legislative change. Other target audiences included researchers and parents. We did not lobby for policy change due to restrictions placed on using federal funds for lobbying purposes [18]. However, we strategically shared our data with organizations that carry out lobbying and advocacy activities related to skin cancer prevention as part of their mission (e.g., the American Academy of Dermatology Association (AADA), the advocacy organization of the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD)).

Fig 1.

CITY100 dissemination target audiences

Project website

A primary method for disseminating CITY100 findings was a project website (www.indoortanningreportcard.com), which included interactive pages for obtaining city- and state-specific data; simple, user-friendly descriptions of key study results and general research linking indoor tanning with skin cancer; a personal story of Miss Maryland, a former indoor tanner and melanoma survivor; and concrete recommendations tailored to various stakeholder groups (i.e., media specialists or reporters; legislators, policy specialists, or lobbyists; health professionals or teachers; concerned parents; and teens).

We worked with a local web design team to create a user-friendly website and housed it on a nonacademic server to facilitate use among nonacademic audiences. The website homepage appears in Fig. 2, and Fig. 3 presents a website interactive page displaying the number of tanning salons in San Diego compared with national rates and the number of Starbucks and McDonald's.

Fig 2.

CITY100 dissemination website homepage

Fig 3.

CITY100 dissemination website tailored statistics sample page

To promote website use, study staff and investigators sent several mass distribution emails to target audiences, encouraging them to visit the website. Additionally, the website link was included in press releases and in all other communications with target audiences. CITY100 website access was tracked using Google Analytics [19]. Between the May 2009 website launch and May 2010, there were 2,255 total visits (1,655 unique visitors). The average time spent per visit was 2 min and 40 s, with an average of 3.68 page views. Excluding the homepage, the top five pages viewed in descending order were as follows: (1) CITY100 findings, (2) background literature on the link between indoor tanning and skin cancer, (3) interactive pages on number of tanning salons and on state laws, (4) overview of CITY100, and (5) tailored recommendations. See Table 1 for top website users by state and institution type. Interestingly, website use increased in the website's second year (May 2010–May 2011; 2,778 visits (2,302 unique visitors)), suggesting that the website remained a valuable resource.

Table 1.

CITY100 dissemination website use statistics by top state and institution type in year after website launch (May 2009–May 2010)

| Total visits | % of visits | |

|---|---|---|

| Top 10 visitors by statea | ||

| California | 263 | 14.7 |

| New York | 181 | 10.1 |

| Pennsylvania | 144 | 8.1 |

| Ohio | 127 | 7.1 |

| Illinois | 103 | 5.8 |

| Massachusetts | 78 | 4.4 |

| Texas | 72 | 4.0 |

| Maryland | 68 | 3.8 |

| Florida | 52 | 2.9 |

| Michigan | 48 | 2.7 |

| Top 5 visitor institution typesb | ||

| Universities | 116 | 8.0 |

| Advocacy or health organizations (general)c | 108 | 7.4 |

| Federal, state, city, or county governmentd | 78 | 5.3 |

| Skin cancer advocacy organizations | 29 | 2.0 |

| Health departments | 29 | 2.0 |

a1,787 visits made from United States users

b1,459 visits made by 100 top service providers; identifiable visitors are presented (the majority of visits were made by unidentifiable sources such as Comcast cable)

cIncludes hospitals, organizations such as the American Cancer Society, the Environmental Protection Agency, the National Institutes of Health, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

dIncludes international governments

Communication with media

We sought to increase public awareness via the news media, with press release distribution and interviews timed around the publication of three peer-reviewed manuscripts: (1) data on the relatively higher numbers of tanning salons compared to Starbucks and McDonald's [8], which subsequently led to heavy media attention primarily via local media outlets around the US; (2) data on compliance of tanning salons with laws and FDA recommendations [9], which was featured on Good Morning America (GMA), National Public Radio (NPR), and in dozens of other national news reports; and (3) data demonstrating that current indoor tanning laws do not reduce youth indoor tanning [6], which was featured in local and national media outlets, including a piece on ABC news. Please refer to the following stories for examples of CITY100 media coverage: http://abcnews.go.com/video/playerindex?id=8638018 (GMA), http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/29552556/ns/health-skin_and_beauty/t/many-cities-tanning-salons-exceed-starbucks/#.UBgEko5qPFI (MSNBC), and http://www.npr.org/blogs/health/2009/09/tanning_salons_lax_on_rules_ab.html (NPR).

Communication with stakeholders

As noted above, we strongly emphasized partnership with influential stakeholders. Partners included the AADA, the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network (ACS CAN), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), AIM at Melanoma, and the National Council on Skin Cancer Prevention. Communication with partners was frequent and both informal and formal. One of several critical formal interactions was an invited presentation of key CITY100 findings by CITY100's principal investigator at an ACS-sponsored meeting on October 5–6, 2011 in Atlanta focused on legislative approaches to reducing indoor tanning, “National Meeting to Develop an Advocacy and Research Strategy to Dramatically Reduce Tanning Bed Use among Teens and Young Women.”

IMPACT ON POLICY

In late 2011, California passed the first US state law to ban indoor tanning among those under 18 with Senate Bill 746 (Lieu) [20], and CITY100 data were used to support this legislative action. Likewise, CITY100 data were used by ACS in expert testimony for promoting a ban on indoor tanning for teens in Howard County, MD, USA; this was the first local jurisdiction to ban indoor tanning for youth under age 18 [20]. CITY100 data were also used by the Ohio Dermatological Association in their efforts to pass a stricter Ohio law; the Michigan Department of Community Health; a state Attorney General's office, who will replicate the salon practices study; the AAD in an FDA hearing; and litigators filing a class action lawsuit.

To understand CITY100's impact on California's indoor tanning ban, we interviewed several of our key stakeholders: Samantha Guild, Patient Advocate from AIM at Melanoma; Sophie Balk, MD, Former Chairperson of the AAP Committee on Environmental Health; and Bruce Brod, MD, State Policy Committee Chair of the AADA.

Each of our stakeholder partners said that CITY100 data were instrumental in promoting California's legislative change. For example, Bruce Brod of the AADA said, “the CITY100 data was a part of pro-advocacy arguments there [California] and continue to be an important part of our efforts across the nation. Research on the tanning industry, particularly demonstrating that current parental consent laws aren't being enforced and therefore aren't effective are crucial for our collective efforts to further and better regulate this burgeoning industry.” When asked which CITY100 data were useful in their legislative advocacy efforts, our stakeholder partners highlighted data on the ineffectiveness of current indoor tanning laws and the prevalence comparisons between indoor tanning salons and Starbucks and McDonald's. For example, Samantha Guild of AIM at Melanoma said, “in the campaign to pass indoor tanning legislation, AIM at Melanoma used the CITY100 data to show legislators that parental consent laws are ineffective and a total ban is necessary to ensure that minors are protected from the dangers of indoor tanning beds.” Sophie Balk of the AAP said, “the information about how many tanning facilities there are in each city was very useful. It was surprising to learn how common it is to have a tanning facility in cities. It was especially useful to have the information comparing the density of tanning facilities with the density of McDonald's and Starbucks.” Our partnership with stakeholder organizations proved invaluable in promoting policy change.

LESSONS LEARNED

Our research team learned a number of critical lessons throughout the CITY100 project and its dissemination phase. We share these lessons below.

Working with media is essential in the dissemination process

In the planning phase of data collection, consider attractiveness of data to media. Early in our data collection process, we were cognizant of what may pique the attention of the public, and hence, the news media. For example, although it was not initially an aim of the parent grant, we decided that collecting data on the number of at least one ubiquitous institution such as Starbucks would provide audiences with a context for the number and density of tanning salons in their cities. It is important to collaborate with an experienced media specialist prior to or immediately after manuscript submission. He or she should generate news stories and train your research team to give effective interviews.

Create user-friendly, interesting ways to present your results and recommendations

Whether through our website or other forums (e.g., formal presentations), we emphasized using colorful and easy-to-understand visual depictions of our data. We worked hard to isolate our most important and interesting findings for broad communication purposes, whereas we presented our more complex and/or methodologically oriented study findings in traditional peer-reviewed research publications.

Promote use of your data broadly and often

It is critical to bring target audiences' attention to your dissemination messages often. Our primary mechanism of communicating the CITY100 study findings was through the study website, which we promoted to a number of key target audiences. Without frequent promotion of its use, this resource may have been underutilized. Our dissemination activities started prior to the widespread use of Facebook and Twitter, both of which enable frequent messaging to large audiences; if we had capitalized on these dissemination channels, it likely would have enhanced reach to several target audiences (e.g., media, legislative advocacy groups, and parent and adolescent consumers). Future dissemination advocacy efforts should integrate messaging through Facebook and Twitter channels.

Collaborate and share data with relevant health organizations

A critical step in our dissemination efforts was to identify and partner with health organizations. Health organizations are well-equipped and experienced with communicating to the public and policymakers. Without their partnership, it is unlikely that CITY100 findings would have had the reach and impact that they did.

Policy implications of your data should be considered in each stage of your research

Policy change is potentially one of the most wide-reaching methods for shaping health behavior and health. Substantial effort should, therefore, be put into understanding the policy implications of your work and the mechanisms for enacting policy change relevant to your research. If federally funded, be cognizant of antilobbying laws [18].

Selecting the primary dissemination audience involves making difficult choices about who will receive the study messages

Other audiences would likely have benefitted from learning about CITY100 findings (e.g., schools and adolescent and parent organizations). However, given limited dissemination funds and time, we prioritized disseminating findings to legislative advocacy audiences rather than directly to adolescent and parent consumers. We made this decision in light of the potential for policy change to have a significant public health impact. Unfortunately, we are unable to quantify our reach to adolescents and parents, but given that the majority of visits to the CITY100 website were made by unidentifiable sources such as Comcast cable, it is possible that some of the CITY100 website users were constituted by such audiences.

CONCLUSION

These recommendations based on the lessons we learned from CITY100 have the potential to generalize to many other content areas in addition to that of policies protecting consumers from the risks of indoor tanning. The recommendations are, by design, overlapping, and dissemination interventions should be developed using them in an integrative manner. We hope that the information in this paper will encourage more health researchers to begin to proactively address the policy implications of their data and to design relevant, effective dissemination strategies.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a National Cancer Institute Dissemination Supplement: Parent Grant #R01CA093532. We thank our collaborators Drs. Moshe Engelberg, Jean Forster, Debra Haire-Joshu, James Sallis, and Martin Weinstock; Debra Rubio, Dalila Butler, and Nicole Pizzi who provided research administration support to the dissemination activities; and the MET Team, who created our dissemination website.

Conflict of interest

None.

Footnotes

Dr. Hoerster was with the SDSU/UCSD Joint Doctoral Program in Clinical Psychology and the San Diego State University Graduate School of Public Health at the time of the CITY100 dissemination project.

Implications

Practice: To encourage large-scale health behavior change, it is important for researchers to partner with media and invested healthcare organizations to disseminate key study findings.

Policy: Policy implications of research data should be considered and emphasized at each stage of the research process.

Research: Researchers engaged in novel dissemination approaches should track and study the dissemination process so that future researchers can learn from these endeavors.

References

- 1.Lazovich D, Vogel RI, Berwick M, Weinstock MA, Anderson KE, Warshaw EM. Indoor tanning and risk of melanoma: a case–control study in a highly exposed population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(6):1557–68. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gallagher RP, Spinelli JJ, Lee TK. Tanning beds, sunlamps, and risk of cutaneous malignant melanoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(3):562–6. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.International Agency for Research on Cancer Working Group on artificial ultraviolet (UV) light and skin cancer The association of use of sunbeds with cutaneous malignant melanoma and other skin cancers: A systematic review. Int J Cancer. 2007;120(5):1116–22. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buller DB, Cokkinides V, Hall HI, et al. Prevalence of sunburn, sun protection, and indoor tanning behaviors among Americans: Review from national surveys and case studies of 3 states. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(5 Suppl 1):S114–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sallis JF, Owen N, Fisher EB. Ecological models of health behavior. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanth K, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. 4. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2008. pp. 465–86. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayer JA, Woodruff SI, Slymen DJ, et al. Adolescents' use of indoor tanning: A large-scale evaluation of psychosocial, environmental, and policy-level correlates. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(5):930–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woodruff SI, Pichon LC, Hoerster KD, Forster JL, Gilmer T, Mayer JA. Measuring the stringency of states' indoor tanning regulations: instrument development and outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(5):774–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoerster KD, Garrow RL, Mayer JA, et al. Density of indoor tanning facilities in 116 large US cities. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(3):243–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pichon LC, Mayer JA, Hoerster KD, et al. Youth access to artificial UV radiation exposure: practices of 3647 US indoor tanning facilities. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(9):997–1002. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. Fact sheet no. 287: Sunbeds, tanning, and UV exposure. Available at http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs287/en/index.html. Accessibility verified August 6, 2012.

- 11.Sinclair C. Banning the tan around the world: Nations mobilize. News from the International Advisory Council. Available at http://www.gowithyourownglow.net/images/stories/2010_Journal/IntlAdvisoryCouncilNews.pdf. Accessibility verified August 6, 2012.

- 12.Christoffel KK. Public health advocacy: process and product. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(5):722–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.90.5.722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoerster KD, Mayer JA, Woodruff SI, Malcarne V, Roesch SC, Clapp E. The influence of parents and peers on adolescent indoor tanning behavior: findings from a multi-city sample. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(6):990–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayer JA, Hoerster KD, Pichon LC, Rubio DA, Woodruff SI, Forster JL. Enforcement of state indoor tanning laws in the United States. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5(4):A125. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henry GT, Gordon CS. Tracking issue attention: specifying the dynamics of the public agenda. Public Opin Q. 2001;65(2):157–77. doi: 10.1086/322198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Downs A. Up and down with ecology: the “issue-attention cycle”. The Public Interest. 1972;28:38–50. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newig J. Public attention, political action: the example of environmental regulation. Ration Soc. 2004;16:149–90. doi: 10.1177/1043463104043713. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Institutes of Health. Ethics program: Lobbying activities. Available at http://ethics.od.nih.gov/topics/lobbying.htm. Accessibility verified August 6, 2012.

- 19.Google. Google Analytics. Available at http://www.google.com/analytics/. Accessibility verified August 6, 2012.

- 20.National Conference of State Legislatures. Indoor tanning restrictions for minors—A state-by-state comparison. Available at http://www.ncsl.org/issues-research/health/indoor-tanning-restrictions-for-minors.aspx. Accessibility verified August 8, 2012.