ABSTRACT

Almost 35 million U.S. smokers visit primary care clinics annually, creating a need and opportunity to identify such smokers and engage them in evidence-based smoking treatment. The purpose of this study is to examine the feasibility and effectiveness of a chronic care model of treating tobacco dependence when it is integrated into primary care systems using electronic health records (EHRs). The EHR prompted primary care clinic staff to invite patients who smoked to participate in a tobacco treatment program. Patients who accepted and were eligible were offered smoking reduction or cessation treatment. More than 65 % of smokers were invited to participate, and 12.4 % of all smokers enrolled in treatment—30 % in smoking reduction and 70 % in cessation treatment. The chronic care model developed for treating tobacco dependence, integrated into the primary care system through the EHR, has the potential to engage up to 4.3 million smokers in treatment a year.

KEYWORDS: Chronic care smoking treatment, Translational research, Smoking cessation, Primary care, Recruitment, Electronic health record

INTRODUCTION

Primary care clinics provide a critical venue for offering tobacco dependence interventions to smokers. Smokers make regular healthcare visits, and a clinical intervention as brief as 3 min can improve patients’ chances of quitting [1]. Helping smokers quit could reduce the risk for seven of the top ten causes of death and save patients an average of 14 years of life [2].

However, it has been difficult to ensure that healthcare settings consistently provide evidence-based tobacco dependence treatment, even though these treatments can double or triple smokers’ success rates [1]. While 80 % of smokers in the U.S. (almost 35 million people) see a primary care clinician each year and approximately 70 % want to quit smoking, fewer than half of smokers report being advised to quit by their primary care clinician in the past year, and only about 25 % receive evidence-based counseling and/or medication [3, 4]. A recent population-based survey found that among smokers and smokers who had quit in the last 2 years, less than one third had used evidence-based treatment (counseling and/or medications [4]). Thus, new, more effective methods are needed to increase the percentage of smokers who receive advice to quit and assistance in quitting in the primary care setting.

Progress has been made in translating efficacious cessation interventions to diverse patient populations in primary care settings (e.g., [3, 5–7]). Direct outreach to primary care patients through mailings can increase engagement in evidence-based cessation treatment [8]. However, smokers offered cessation interventions at a primary care clinic visit, versus mass mailings, are more likely to participate in treatment and be successful in their quit attempts [9].

This paper describes a recruitment strategy designed to efficiently offer treatment to smokers visiting primary care clinics and increase the number of smokers who engage in treatment (i.e., volunteer for and participate in treatment). The current recruitment strategy was guided by a chronic disease management, or chronic care, approach (e.g., [10, 11]). In 2000, the Public Health Service Guideline: Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence called for clinicians to treat tobacco use and dependence as a chronic disease, similar to the model recommended for treating hypertension, hyperlipidemia or diabetes [12]. The chronic care or chronic disease management model holds that care of chronic conditions can be enhanced via improvements in six different dimensions: organizational support, community linkages, decision support systems, self-management support, delivery system design, and clinical information systems.

The current paper reports the development of a chronic care approach to smoking that includes changes in three dimensions: self-management support (involving multiple smoking treatment elements appropriate for a broad range of smokers), delivery system design (using specialist smoking cessation case managers), and an enhanced clinical information system (a modified electronic health record, EHR). We focused on these three elements because we believed that these held the greatest potential for improving recruitment and treatment engagement. For instance, we concluded, based on evidence from prior research [13–15] on engaging smokers not ready to quit in various types of treatment, that offering smoking treatment to smokers unmotivated to quit (expanding the range of self-management support) would increase the population of smokers available for recruitment. We believed that using smoking specialist case managers for offering and delivering treatment (a delivery system design element) would be especially effective because it would remove burden and shift responsibility from busy primary care clinicians. Finally, prior promising results with EHR support systems suggested that this strategy could boost the systematic identification of smokers and the offer of treatment [16–19]. We chose not to target organizational support because we already had strong organizational support for treating tobacco dependence. In addition, our use of case managers, and the availability of strong treatment resources provided by the research program, reduced the need for the stronger community linkage element. Finally, although it was not targeted in the current research, we believe that improved decision making support strategies (e.g., guidance in deciding when to quit for those who have reduced their smoking) could be an important topic for future research efforts.

Chronic care models are intended to provide support and intervention to a broad range of patients across the course of a disease. This was achieved in the present study by broadening the scope of self-management support to target smokers not yet ready to make a quit attempt (those in the motivation phase) [20] as well as to those interested in receiving cessation treatment. Previous research has shown all smokers can benefit from treatment even if they are not currently willing to quit [20–24]. Such “unmotivated” smokers are often willing to engage in treatment that can reduce the number of cigarettes they smoke and/or increase their motivation to quit or success in quitting [1, 13, 25, 26]. The 2008 PHS Guideline recommends motivational interventions for smokers in this phase [1].

Although randomized efficacy trials have supported the value of interventions for unmotivated smokers, little is known about the value of such interventions in real-world healthcare settings. For instance, it is not known how many smokers would volunteer for such treatments or actually engage in them. The current research sheds light on the potential patient utilization and acceptability of such treatments as they might be used in primary care.

The second chronic disease management model dimension modified in the current study was a delivery system design change. The current study used smoking case managers (health educators) to deliver the smoking cessation interventions (e.g., [27]) and adopted a team approach [10, 28–30] to smoking intervention in which clinic medical assistants (MAs) performed initial patient recruitment, case managers delivered the interventions, and clinic physicians reinforced the interventions (cf, [31]). This approach is similar to the use of a team approach for diabetes involving the assessment of diabetes by a physician with referral to a health educator for diabetes management [27]. While clinic staff can reliably and efficiently identify smokers (e.g., via the expanded vital signs, EHRs; [1]), specialists/case managers have the time, training, and resources to deliver treatments appropriate to the smoker’s situation. The specialist can also ensure treatment continuity over time; tracking the course of treatment and the smoker’s status to permit appropriate treatment modification.

The current research used a modified EHR—the third dimension of the chronic care management model addressed in this research—to organize, prompt, and track elements of treatment engagement and support communication within the clinical team. Use of EHRs has increased dramatically throughout the U.S. over the last 5 years, from approximately 17 % of physicians using EHRs in 2008 [32], to 48.3 % of office-based physicians using them in 2009 [33]. The Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act has set EHR adoption standards and calls for incentives for use and penalties for nonuse (e.g., beginning in 2015, hospitals and doctors will be subject to financial penalties from Medicare if they are not using EHRs [34]). Thus, EHRs will be a major resource for organizing and influencing healthcare practices throughout the United States. The current research involves a modest attempt to modify the EHR to facilitate a chronic care approach to tobacco intervention.

Other research has explored the ability of the EHR to facilitate the provision of evidence-based smoking cessation treatment (see [35, 36]), including prompting or guiding: (1) the documentation of tobacco use [17, 18, 37, 38]; (2) the provision of evidence-based treatment [18, 39]; (3) quit line referral [16, 39, 40]; and (4) guideline adherence [41]. In the present research, the EHR was modified to: (1) prompt MAs to assess smoking status; (2) provide the MAs with a script to ask patients about their interest in smoking treatment; (3) provide the MAs with a timely, easy and efficient means of alerting the smoking treatment team about interested patients; and (4) communicate research treatment back to the referring clinician.

The current research

This paper describes the implementation of a real-world smoking intervention guided by a chronic care management model. The intervention occurred in selected primary care clinics within participating healthcare systems, targeted a broad range of smokers (those willing and unwilling to make a quit attempt), involved a team approach to intervention (involving medical assistants, case managers, and clinic primary care physicians), and used a modified EHR to facilitate treatment recruitment and team communication. The implementation of this intervention, guided by a chronic care approach, required integration of the recruitment procedures into clinic work flow, training of clinic staff, and systemic changes in clinic EHRs to prompt treatment invitations, share information across team members, and track participating patients. The current paper focuses on the effectiveness of this particular chronic care-based approach in terms of recruitment and treatment engagement. Clinic staff performance in smoker identification and treatment invitations was used to determine whether this strategy was feasible, acceptable to clinic staff and effective in recruiting smokers. Treatment engagement was evaluated based on smokers’ interest and involvement in both motivational and cessation treatments. In addition, this research examined whether person-factors (i.e., gender, race, age or cigarettes smoked per day) were related to rates of enrolling in treatment, clinic staff’s acceptance of their new responsibilities, and other outcomes.

METHODS

Clinics

Nine Internal Medicine and Family Medicine clinics from two large healthcare systems in south-central and southeastern Wisconsin participated in this research. The healthcare systems were chosen because they: (1) have numerous medium and large-sized clinics in the defined catchment area; (2) have EHRs they were willing to modify as part of their research collaboration; and (3) are strongly supportive of improving smoking interventions for their patients. Individual clinics were chosen based on: (1) clinic size (the goal was to include clinics with at least five to eight full-time providers, a size that was judged to permit sufficient smoker recruitment to justify placement of two full-time research staff/case managers at each clinic); (2) EHR status; (3) location; and (4) clinic willingness to participate, including ability to provide at least two spaces for staff to meet with patients and store materials.

Procedure

The clinic’s EHR was modified prior to launching the study in a particular clinic (see [42]). The modified EHR guides the assessment of smoking status as part of the vital signs assessment and then cues the MA, or other staff person who collects vital signs, with specific text (Fig. 1) to invite smokers to learn more about the smoking treatment options available as part of a research study. If a patient agrees to the referral, the MA then clicks the referral button and the patient’s contact information is electronically sent via a secure link to the research study office. As part of clinic staff training, MAs were instructed to read at each clinic visit the specific study invitation text provided in the modified EHR to all patients who reported current smoking, unless the EHR noted that the patient had already enrolled in the study. The script for a subsequent invitation was slightly modified so that it began with, “You may have been asked this before…” and then continued with the standard invitation text.

Fig 1.

Referral script for medical assistants to read to all smokers

Prior to beginning recruitment in a clinic, research staff briefed the MAs on the goals of the research and trained them on how to navigate the modified EHR. There was also an information session specifically for the physicians and other primary care clinicians. This session was designed to increase interest and buy-in among the practitioners so that they would, in turn, encourage clinic staff to refer patients. Research staff implemented several procedures to increase referral rates including: (1) informing clinic staff about the study and answering questions; (2) setting clinic recruitment goals (e.g., an invitation rate of at least 75 % with performance data shared weekly); (3) providing nominal incentives (e.g., pizza party, bagels), which were sometimes contingent on meeting clinic goals; (4) showing clinic staff videotaped testimonials of participants from their clinic who were pleased with their study involvement and had made a change in their smoking (see http://www.ctri.wisc.edu/Smokers/smokers_uwpass_videos.html); and (5) providing clinic administration with feedback regarding referral rates. The implementation of the above activities varied from clinic to clinic based on the referral rates and the overall enthusiasm of the clinic manager and staff. Throughout the study, case managers collected informal data from MAs and other clinic staff regarding their thoughts about the study and procedures, including potential barriers to referring patients.

Electronic referrals were sent to the research office via automated email using two methods. One healthcare system sent a single daily report with all the referrals from the previous day; the other healthcare system sent an individual email in real time for each referral. Relevant patient contact information was extracted from the health record and populated the referral email, which the research staff entered into a research database daily. Research staff then phoned patients, within two business days of receiving the referral, to explain the treatment options, screen them to ensure the research was appropriate and then invite them to participate. This research comprises three large, factorial intervention studies [20, 43]. One study (Project 1) was designed to increase motivation to quit and reduce smoking among smokers not interested in quitting at the time of the invitation. The other two studies (Projects 2 and 3) included participants who expressed interest in smoking cessation (and were willing to set a quit date) and were designed to evaluate phase-specific cessation and medication adherence interventions (cf. [20]).

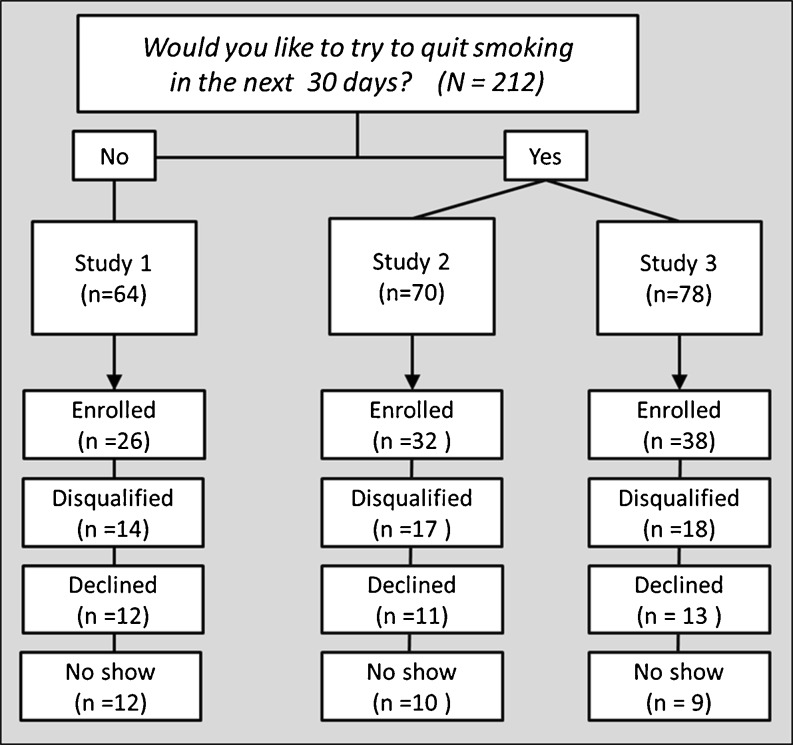

Upon contacting the referred smoker by phone, a research staff member determined whether the smoker would be assigned to the reduction/motivation project (Project 1) or randomized to one of the two cessation projects (Projects 2 and 3 which were only open to smokers willing to make a quit attempt). Initially assignment was done via the question: “Would you like to try to quit smoking in the next 30 days?” with patients who reported interest in quitting in the next 30 days being randomized to a cessation treatment. During the course of the trial we revised this procedure and allowed patients to select the type of treatment (cessation vs. reduction/motivation) by asking, “Our research program has two tracks—one for smokers who are ready to quit in the next month and one for smokers who are interested in cutting down. Which track would you be interested in?”

After potential participants selected their treatment track (i.e., cessation or reduction/motivation), they were told about the treatments and requirements for their specific study. Those interested in participating were then assessed for eligibility. The inclusion/exclusion criteria for the three studies were designed to ensure that participants were willing and able to safely participate and complete the various studies. These criteria included: (1) being at least 18 years old; (2) being able to read and write English; (3) smoking at least five cigarettes per day for the past 6 months; (4) not currently taking bupropion (Wellbutrin™, Zyban™) or varenicline (Chantix™); (5) planning to remain in the area for the duration of the study (6–12 months); (6) willing and able to use the nicotine patch and nicotine gum; (7) not hospitalized for a stroke, heart attack, congestive heart failure or diabetes in the last year; (8) no history of psychosis or bipolar disorder; and, (9) women reporting they were not pregnant or nursing and that they were willing to use acceptable birth control for the duration of treatment.

Eligible participants were then scheduled to attend an initial research visit. All research visits occurred at the patient’s referring clinic. If the patient attended the initial clinic visit and provided written informed consent (i.e., the patient enrolled), s/he was randomly assigned to a treatment condition and treatment was initiated. Information about treatment assignment was emailed back to the referring primary care clinician and any medication regimen was then entered into the EHR by clinic staff. Participants were compensated for their participation in research activities ($25 for the first visit and up to $95 total in Project 1, $10 for the first visit and up to $50 total in Project 2, and $10 for the first visit and up to $80 total in Project 3) at the end of their participation (i.e., after their last research contact).

RESULTS

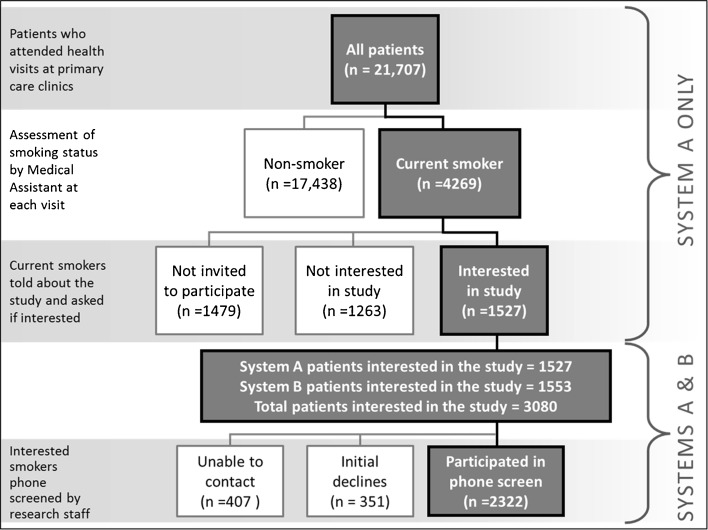

We report recruitment, screening, and treatment engagement data that were collected from July, 2010 to December, 2011, representing approximately 50 % of the study recruitment goal. The top half of Fig. 2 illustrates the outcomes of the smoker identification and interest-screening steps in one of the healthcare systems (only available for System A). The two healthcare systems use different EHR software platforms, and the data from System B are organized by encounter, rather than by individual patients. Therefore, they do not have the same denominator for comparisons (i.e., some patients will have multiple visits to a clinic during the study period, and one healthcare system counts each visit rather than counting the individual patient). Individual patient data will ultimately be extracted from both healthcare systems, but for System B this data will come from its database at the end of the study, and not from its EHR.

Fig 2.

Flow of patients into study referral as of December, 2011. Note. Initial decline = participant declined to hear more about the study and did not complete a phone screen

Rates of treatment invitations and acceptance

Smokers represented approximately 20 % of the patient population (n = 4269) in participating System A primary care clinics (see Fig. 2). Almost two thirds (65.3 %; n = 2790) of the identified smokers were invited by an MA to participate in the current research. Informal discussions with MAs and clinic staff attempted to discern why one third of participants were not invited to participate. Reasons given included difficulty managing workflow (i.e., MAs who already struggled with managing workflow tended to refer fewer patients than those who were better able to manage the standard clinical tasks) and reluctance to refer a patient when the MA was himself/herself a smoker.

More than half the smokers who were invited to participate accepted the invitation and were referred to the study (54.8 %, n = 1527; 35.8 % of all identified smokers who attended a visit at the primary care clinic). Despite the fact that the program was offered in all clinics for at least 6 months, we found that only 201 patients received a second invitation after initially declining. However, 14.4 % (29 out of 201) of the patients who received a second invitation changed their mind and accepted an invitation to participate at a subsequent clinic visit.

Of the 3,080 referred patients (from both Systems A and B), 75.4 % (n = 2,322) were successfully contacted by the research staff, agreed to learn more about the research, and completed a telephone screen (13.2 % of referred patients could not be contacted by phone). Only 11.4 % (n = 351) of the referred patients were not interested in hearing more about the study.

Rates of enrollment in cessation and reduction treatments

Almost one third (29.4 %) of patients who completed the phone screen indicated they were interested in cutting down rather than quitting and so were assigned to Project 1, the trial for smokers not interested in quitting at the time of their screening (see Figs. 3 and 4). Of those offered Project 1 (n = 682), 47.5 % (n = 324) enrolled and initiated treatment. The remaining 70.6 % of patients who completed the phone screen were interested in cessation and they were assigned to Projects 2 (n = 845) or 3 (n = 795), the smoking cessation trials. Patients interested in cessation attended the first study visit (and thereby initiated treatment) at rates similar to those observed among patients interested in reduction/motivation (Project 2 = 44.7 % [n = 378]; Project 3 = 46.4 % [n = 369]). The rates of ineligibility, declining to participate during the phone screen, and not attending the initial study visit were similar for all three trials. Figure 3 illustrates participant flow when patients were assigned to Project 1 vs. Projects 2 or 3 based on their interest in quitting in the next 30 days; Fig. 4 illustrates participant flow when patients selected either reduction/motivation treatment (Project 1) or cessation treatment (Projects 2 or 3).

Fig 3.

Study flow into the three research studies as of December, 2011, based on a phone screen question asking if the patient would like to quit smoking in the next 30 days (first treatment selection script). Note. Enrolled means the patient attended the first study visit

Fig 4.

Study flow into the three research studies as of December, 2011, based on asking patients during the phone screen to choose between a study for smokers who are ready to quit in the next month and a study for smokers who are interested in cutting down (second treatment selection script). Note. Enrolled means the patient attended the first study visit. Screen Passed Thus Far means the patient passed the phone screen but has not yet attended the first study visit

The rates of assignment to Project 1 (reduction/motivation) vs. to Projects 2 and 3 (cessation) were approximately 30 vs. 70 % regardless of whether treatment assignment was based on participants’ reported interest in quitting in the next 30 days or on their specific choice of a treatment for reduction/motivation vs. cessation. However, when participants were allowed to choose between cessation and reduction, the Project 1 enrollment rate increased almost 8 percentage points (from 40.6 to 48.2 %; see Figs. 3 and 4). Given the potential difference among patients who were assigned to Project 1 versus those who opted to enroll in Project 1, we will statistically control for type of recruitment in our future analyses of Project 1 outcomes. The enrollment rates for the cessation treatments decreased minimally following the change (from 45.7 to 44.6 % enrolled for Project 2; from 48.7 to 46.2 % enrolled for Project 3).

In summary, among the smokers presenting to the targeted primary care clinics, 65.3 % were invited to participate; of these, 54.8 % accepted the MA’s offer to learn more about the treatment options; and ultimately, 34.8 % of smokers who were interested in learning more about the study enrolled in one of the treatment programs. This translates to 12.4 % of all smokers who presented for a primary care visit enrolling in a tobacco treatment program (8.7 % in cessation and 3.7 % in non-cessation treatment) as a result of a proactive offer of treatment made by clinic staff at a regular healthcare visit.

Person-factor differences in enrollment

Among the 2,322 people who completed a phone screen and were assigned to either the reduction/motivation trial (Project 1) or one of the cessation trials (Projects 2 and 3), we examined differences in gender, race, age, and cigarettes per day between those who did (approximately 46 %) and did not (approximately 54 %) enroll in the three studies (i.e., attend the initial study visit). In Project 1, there were no gender differences between those who did and did not enroll. However, there was a significant effect of race on enrollment (χ2 (1, 644) = 7.88, p < .01); 52.3 % of white smokers who passed the phone screen went on to enroll (n = 299), compared to 34.7 % (n = 25) of non-white smokers who passed the phone screen. Further, in Project 1, patients who did not enroll after passing the phone screen were younger (M = 44.25, SD = 14.31) than those who enrolled (M = 47.41, SD = 13.88; t = 6.93, p = .009), and enrollees smoked more cigarettes per day (M = 18.25, SD = 7.99) than those not enrolling (M = 16.73, SD = 9.04, t = 4.48, p = .04).

For Projects 2 and 3, the cessation trials, there were no significant differences in gender or race in enrollment. For smokers assigned to Project 2, enrollees were older (M = 46.54, SD = 12.13) than those who did not enroll (M = 42.29, SD = 13.90, t = 19.19, p = .01), and enrollees smoked more cigarettes per day (M = 18.43, SD = 8.16 vs. M = 16.68, SD = 9.75, t = 6.80, p = .009). Similarly, for smokers assigned to Project 3, enrollees were older (M = 46.18, SD = 12.73) than those who did not enroll (M = 42.08, SD = 13.40, t = 16.78, p < .001) and enrollees smoked significantly more cigarettes per day (M = 19.01, SD = 8.69 vs. M = 16.57, SD = 8.55, t = 13.49, p < .001). It should be noted that potential participants had to smoke at least five cigarettes per day to participate, but only 76 of the 2,322 phone screened (3.3 %) were excluded for smoking fewer than five cigarettes per day.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the enrolled participants across the three trials. Participants in all three projects were similar in age and numbers of cigarettes smoked per day, but Project 1 had a somewhat higher rate of women and white smokers.

Table 1.

Demographic and smoking data by research project for participants enrolled as of December, 2011

| Project 1 reduction/motivation treatment (N = 324) | Project 2 cessation treatment (N = 378) | Project 3 cessation treatment (N = 369) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % Women | 64.8 | 54.5 | 57.5 |

| % White | 92.3 | 83.6 | 85.4 |

| % African American | 4.3 | 9.8 | 9.2 |

| % Native American | 1.2 | .5 | .8 |

| % Asian/Pacific Islander | .3 | .8 | 0 |

| % Other race | 1.9 | 5.3 | 4.6 |

| Age (M, SD) | 47.41 (13.88) | 46.51 (12.14) | 46.18 (12.73) |

| Range, 18–79 | Range, 18–78 | Range, 18–80 | |

| Cigarettes per day (M, SD) | 18.25 (8.00) | 18.35 (8.09) | 19.01 (8.69) |

| Range, 5–40 | Range, 5–50 | Range, 5–70 |

DISCUSSION

This research implemented a set of interventions, based on the chronic care model, to recruit smokers into tobacco use treatment in a comprehensive, efficient manner. The model comprised: (1) an offer of barrier-free access to an expanded range of smoking interventions provided at primary care clinics; (2) use of an integrated team approach for recruitment and treatment; and (3) use of modified EHR functions. As a result of these recruitment procedures, approximately two thirds of smokers received invitations to participate in treatment and more than half of those invited accepted the treatment invitation. Smokers were interested in both cessation and reduction/motivation treatment options, with those who were older and smoking more cigarettes per day being more likely to enroll in any treatment. Below, we discuss these findings in the context of their public health and clinical significance and describe clinic staff perspectives regarding the feasibility and acceptance of this research.

This research shows that the developed chronic care model of treating smokers, facilitated by an EHR system, has the potential to expand the reach of evidence-based treatment. This potential expanded reach resulted, in part, from the inclusion of smokers who did not want to quit at the time of their clinic visit but were interested in cutting down. By recruiting patients interested in reducing their smoking, overall treatment engagement among smokers was increased by about one third. Thus, the current results suggest that self-selection of reduction/motivation vs. cessation treatment may be important in getting more smokers to engage in treatment. When treatment assignment changed from being based on interest in quitting in the next 30 days to being based on each patient’s preferred treatment goal (quitting vs. cutting down) we found that similar numbers of smokers were eligible for Project 1 (the reduction/motivation study) but that when participants chose their treatment goal, they were more likely to follow through and actually enroll in Project 1. This is consistent with some healthcare literature that demonstrates that personal choice increases compliance and follow-through [44, 45]. Also, it may merely be the case that stated intention to quit within the next 30 days (versus treatment selection) is simply a very inaccurate gauge of willingness to engage in treatment [46]. Of course, the public health value of engagement in smoking reduction treatment depends upon the long-term consequences of such engagement in real-world settings, but smoking reduction does seem to make it more likely smokers will successfully quit later on [47, 48].

The data we present on rates of treatment invitation and treatment acceptance would be more meaningful if we could cleanly compare such rates with those obtained with other health care system interventions designed to promote the same goals. Such comparisons are difficult for several reasons. For instance, studies in this area involve very different types and intensities of smoking interventions to which patients are referred: e.g., in-clinic advice to quit versus intensive intervention requiring referral. Such features of the smoking treatment itself could affect patient willingness to accept a treatment offer (analysis is even more complex when the type or cost of the smoking intervention is itself considered part of the health care system change: e.g., [49]). In addition, the outcome data for treatment engagement differ greatly, ranging from records of filled prescriptions to patient recall in exit interviews that smoking was addressed (and sometimes it is not possible to synthesize the outcome data across acceptances of different treatment options). Moreover, some studies do not even report such outcomes as the offer of treatment (e.g., [50]). Further, the complexity and costs of the health care system changes differ greatly with some involving multi-component interventions (e.g., comprising an on-call counselor, free medication, staff training, academic detailing and so on; [51]) and some only provision of a stamp to encourage smoker identification [52].

While comparison is difficult because of the complexities noted above, when a body of relevant studies is examined (i.e., those that tested innovations designed to promote the offer of smoking cessation treatment or assistance as reviewed by Papadakis et al. [53]), some comparable studies are identified. For instance, a study by Bentz et al., [16] showed that provider feedback resulted in a successful smoker referral rate to a quitline of about 4 % (from among identified smokers). In the current study the rate of smokers accepting referral (i.e., expressing interest in the study and accepting the referral offer) was about 36 % (see Fig. 2, System A). Just under 3 % of smokers in the Bentz study actually received quitline counseling; in the current research about 12 % of smokers in System A actually enrolled in treatment. In addition, previous research has found that physician referrals per se have limited effects regarding recruitment of participants for smoking cessation trials [54]. Further, recruitment by research personnel in clinical settings has not consistently worked well. For instance, in the 1980s, researchers found that only 14 % of eligible smokers who were referred to participate in a smoking cessation class actually investigated the class [55]. Some comparison data show more impressive outcomes, however. For instance, studies that target in-clinic intervention when the smoker is identified tend to yield higher levels of treatment acceptance and delivery (e.g., [49, 50, 56]). In one study that included a system intervention that involved EHR strategies, increased medication availability, direct provision of intervention in the primary care clinic (versus referral), and repeated site visits, almost 70 % of identified smokers received counseling, with about 11 % getting some form of cessation medication [50]. Thus, this approach appeared to result in very high levels of counseling and moderately high levels of medication provision (the current study produced a similar level of medication provision; 12 %). Data from that study have to be interpreted, though, with an awareness that the data on counseling occurrence come from medical record review and might have involved only advice to quit. This illustrates the difficulty of making strong inferences from disparate data sources. In sum, a definitive evaluation of the health care system innovations used in the current research must await further research in which such innovations are tested against alternative approaches.

The rate of treatment engagement obtained in the current study could have strong public health impact given that 70–80 % of the 43.4 million smokers in the U.S. see a primary care clinician each year [4, 57–59]. Universal implementation of this model could have the substantial effect of 19.8–22.7 million smokers being invited to participate in treatment and 3.8–4.3 million smokers receiving treatment each year.

While this EHR-based chronic care model appeared acceptable to clinic staff, they failed to invite almost one third of the smokers to participate in the research. Despite apparent general enthusiasm for the research and the fact that most MAs reported that the EHR referral system was easy to learn, systems-level, clinic-specific, and individual factors appeared to suppress invitation rates. At the systems level, one factor that may have suppressed invitation rates was that documenting smoking status and reading the research invitation script for smokers were not mandatory fields in the EHR. In one healthcare system, the MAs had to remember to open the invitation text on their screens after a smoker was identified (rather than having the invitation appear automatically as a pop-up). At the clinic level, the degree of involvement of the clinic manager appeared to be critical for recruitment. At some clinics, the clinic manager effectively intervened with recalcitrant MAs, while at other clinics the manager was much more passive in the face of low invitation rates. MA motivation and support also seemed to be an important determinant of MA performance. For example, providing MAs feedback on their performance and setting invitation goals with nominal contingent rewards for clinic staff proved helpful (e.g., a pizza party for inviting at least 75 % of smokers to participate in the program for three consecutive weeks). With respect to individual factors, some of the participating MAs felt uncomfortable talking to patients about their smoking; MA invitation rates ranged from less than 10 % to almost 90 %. Some MAs were smokers themselves, which may have increased their discomfort (data on MA smoking rates were not collected). In addition, as is typical in most clinics, there were “float” MAs whose temporary assignment to the target clinics resulted in less training regarding the protocol. Given that a third of smokers were not asked about their interest in receiving treatment, increasing treatment invitation rates remains an important route to even higher rates of smoking treatment engagement.

The acceptability of this recruitment system is suggested by our ability to maintain recruitment levels over extended periods of time. We originally planned to recruit for only 6 months in each clinic, believing that interest and clinic staff engagement as well as the number of new, uninvited smokers, would diminish over time. In contrast, our experience has been that, in some clinics with weekly patient volumes of more than 40 smokers per week, we continued to recruit at a lower, but steady, rate for 12 months or more. In addition, when we have ended recruitment in clinics, we received frequent reports from managerial and clinical staff that they were disappointed the program was ending and their patients would no longer have access to these treatments. This suggests that a systems-based approach that uses the EHR to link patients to evidence-based tobacco treatment is valued, and continues to be utilized, by both clinic staff and their patients over a sustained period of time. Further, this suggests that this system could be sustained using clinic-based case managers who also provide diabetes and other chronic disease management, which has become an commonly used service delivery model in healthcare ([10, 11, 23, 24, 27–29]: see [21, 22, 60, 61] for further discussion of a chronic care approach to smoking).

While these results are promising, we did not compare this recruitment approach with other approaches (e.g., mailed invitations to clinic patients). Therefore, as noted above, the strength of the inferences one can draw from these findings is limited. Other limitations are that certain aspects of the organization support system (e.g., informal incentives for MA performance) might not be easily implemented in some clinic systems and that the current smoker identification and invitation data arise from only one healthcare system. Eventually, we will have access to similar data from the second healthcare system participating in this work. Further, this research occurred in a single state. Future research will be needed to determine whether these results are generalizable to other health care systems, areas of the USA, or countries.

In conclusion, this research illustrates the viability and efficiency of using a chronic care model to treat smokers in primary care settings. This approach comprised key elements of a chronic care or chronic disease management strategy for smoking intervention, including changes in: (1) self-management support (involving multiple smoking treatment elements appropriate for a broad range of smokers: those willing and unwilling to make an immediate quit attempt); (2) delivery system design (using a team approach); and (3) an enhanced clinical information system (a modified EHR). This recruitment strategy resulted in clinic MAs’ efficient referral of smokers to research staff functioning as health educators who provided phase-appropriate interventions within the primary care clinic and coordinated care with the primary care provider. Not only did this approach result in substantial patient engagement in both smoking cessation and reduction/motivation treatments, but incorporating such system-level changes into primary care practice was sustainable for clinicians and support staff. Overall, 12.4 % of patients identified as smokers, who were visiting primary care clinics for regular care, ultimately engaged in tobacco dependence treatment. If implemented broadly, this could result in up to 4.3 million smokers treated annually.

Acknowledgements and funding

We would like to acknowledge the staff at Aurora Health Care and Dean Health System for their collaboration in this research. This research was supported by grant 9P50CA143188-12 from the National Cancer Institute and by the Wisconsin Partnership Program. Dr. Baker was supported via NCI 1K05CA139871. Dr. Cook was supported by K08DA021311.

Footnotes

Implications

Practice: Electronic health records (EHRs) should be used to prompt primary care clinic staff to offer all smokers evidence-based smoking interventions, with treatment provided by non-physician clinical staff.

Policy: Healthcare systems should implement a chronic care approach to treating smokers that uses the EHR to identify and offer treatment to all tobacco users at every visit and then provide care via trained chronic care case managers.

Research: Research needs to determine optimal ways of using the EHR to organize tobacco interventions and the effectiveness of incorporating chronic care approaches (including smoking reduction interventions) into healthcare delivery.

References

- 1.Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, Bailey WC, Benowitz N, Curry SJ, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Public Health Service; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Annual smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and economic costs—United States, 1995–1999. MMWR. 2002;51:300–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ong MK, Zhou Q, Sung HY. Primary care providers advising smokers to quit: comparing effectiveness between those with and without alcohol, drug, or mental disorders. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13:1193–1201. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Quitting smoking among adults - United States 2001–2010. MMWR. 2011;60:1513–1519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wittchen HU, Hoch E, Klotsche J, Muehlig S. Smoking cessation in primary care—a randomized controlled trial of bupropione, nicotine replacements, CBT and a minimal intervention. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2011;20:28–39. doi: 10.1002/mpr.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fiore MC, McCarthy DE, Jackson TC, et al. Integrating smoking cessation treatment into primary care: an effectiveness study. Prev Med. 2004;38:412–420. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stapleton JA, Sutherland G. Treating heavy smokers in primary care with the nicotine nasal spray: randomized placebo-controlled trial. Addiction. 2011;106:824–832. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rigotti NA, Bitton A, Kelley JK, Hoeppner BB, Levy DE, Mort E. Offering population-based tobacco treatment in a healthcare setting: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41:498–503. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smit ES, Hoving C, Cox VC, de Vries H. Influence of recruitment strategy on the reach and effect of a web-based multiple tailored smoking cessation intervention among Dutch adult smokers. Health Educ Res. 2012;27:191–199. doi: 10.1093/her/cyr099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wagner EH. The role of patient care teams in chronic disease management. BMJ. 2000;320(7234):569–572. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7234.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff (Millwood). 2001;20:64–78. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ. Treating tobacco use and dependence: clinical practice guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Public Health Service; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carpenter MJ, Hughes JR, Gray KM, Wahlquist AE, Saladin ME, Alberg AJ. Nicotine therapy sampling to induce quit attempts among smokers unmotivated to quit: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1901–1907. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carpenter MJ, Hughes JR, Solomon LJ, Callas PW. Both smoking reduction with nicotine replacement therapy and motivational advice increase future cessation among smokers unmotivated to quit. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:371–381. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Etter JF, Laszlo E, Perneger TV. Postintervention effect of nicotine replacement therapy on smoking reduction in smokers who are unwilling to quit: randomized trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24:174–179. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000115666.45074.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bentz CJ, Bayley KB, Bonin KE, Fleming L, Hollis JF, McAfee T. The feasibility of connecting physician offices to a state-level tobacco quit line. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frank O, Litt J, Beilby J. Opportunistic electronic reminders. Improving performance of preventive care in general practice. Aust Fam Physician. 2004;33:87–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Linder JA, Rigotti NA, Schneider LI, Kelley JH, Brawarsky P, Haas JS. An electronic health record-based intervention to improve tobacco treatment in primary care: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:781–787. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindholm C, Adsit R, Bain P, et al. A demonstration project for using the electronic health record to identify and treat tobacco users. WMJ. 2010;109:335–340. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baker TB, Mermelstein R, Collins LM, et al. New methods for tobacco dependence treatment research. Ann Behav Med. 2011;41:192–207. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9252-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joseph AM, Fu SS, Lindgren B, et al. Chronic disease management for tobacco dependence: a randomized, controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1894–1900. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benowitz NL. Chronic disease management approach to treating tobacco addiction: comment on “nicotine therapy sampling to induce quit attempts among smokers unmotivated to quit”. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1907–1909. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hung DY, Rundall TG, Tallia AF, Cohen DJ, Halpin HA, Crabtree BF. Rethinking prevention in primary care: applying the chronic care model to address health risk behaviors. Milbank Q. 2007;85:69–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00477.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hung DY, Shelley DR. Multilevel analysis of the chronic care model and 5A services for treating tobacco use in urban primary care clinics. Health Serv Res. 2009;44:103–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00896.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore D, Aveyard P, Connock M, Wang D, Fry-Smith A, Barton P. Effectiveness and safety of nicotine replacement therapy assisted reduction to stop smoking: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009;338:b1024. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lai DT, Cahill K, Qin Y, Tang JL. Motivational interviewing for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010; (1):CD006936. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Aubert RE, Herman WH, Waters J, et al. Nurse case management to improve glycemic control in diabetic patients in a health maintenance organization. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:605–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-8-199810150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wagner EH. More than a case manager. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:654–656. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-8-199810150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coleman K, Mattke S, Perrault PJ, Wagner EH. Untangling practice redesign from disease management: how do we best care for the chronically ill? Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30:385–408. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith SA, Shah ND, Bryant SC, et al. Chronic care model and shared care in diabetes: randomized trial of an electronic decision support system. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:747–757. doi: 10.4065/83.7.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lichtenstein E, Hollis JF, Severson HH, et al. Tobacco cessation interventions in health care settings: rationale, model, outcomes. Addict Behav. 1996;21:709–720. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(96)00030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DesRoches CM, Campbell EG, Rao SR, et al. Electronic health records in ambulatory care—a national survey of physicians. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:50–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0802005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsiao C-J, Hing E, Socey TC, Cai B. Electronic medical record. Electronic health record systems of office-based physicians: United States, 2009 and preliminary 2010 estimates2010: Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/emr_ehr_09/emr_ehr_09.htm.

- 34.Pear R. U.S. issues rules on electronic health records. New York Times. 2010 July 13.

- 35.Boyle R, Solberg L, Fiore M. Use of electronic health records to support smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011; (Issue 12. Art. No.: CD008743). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Boyle RG, Solberg LI, Fiore MC. Electronic medical records to increase the clinical treatment of tobacco dependence: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(6 Suppl 1):S77–S82. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bentz CJ, Davis N, Bayley B. The feasibility of paper-based tracking codes and electronic medical record systems to monitor tobacco-use assessment and intervention in an Individual Practice Association (IPA) model health maintenance organization (HMO) Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4(Suppl 1):S9–S17. doi: 10.1080/14622200210128036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spencer E, Swanson T, Hueston WJ, Edberg DL. Tools to improve documentation of smoking status. Continuous quality improvement and electronic medical records. Arch Fam Med. 1999;8:18–22. doi: 10.1001/archfami.8.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bentz CJ, Bayley BK, Bonin KE, et al. Provider feedback to improve 5A’s tobacco cessation in primary care: a cluster randomized clinical trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:341–349. doi: 10.1080/14622200701188828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sherman SE, Takahashi N, Kalra P, et al. Care coordination to increase referrals to smoking cessation telephone counseling: a demonstration project. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14:141–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Szpunar SM, Williams PD, Dagroso D, Enberg RN, Chesney JD. Effects of the tobacco use cessation automated clinical practice guideline. Am J Manag Care. 2006;12:665–673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fraser D, Baker TB, Fiore MC, Adsit RA, Christiansen BA. Electronic health records (EHR) as a tool for recruitment of participants in clinical effectiveness research: lesson learned from tobacco cessation. Transl Behav Med. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Collins LM, Baker TB, Mermelstein RJ, et al. The multiphase optimization strategy for engineering effective tobacco use interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2011;41:208–226. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9253-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Raue PJ, Schulberg HC, Heo M, Klimstra S, Bruce ML. Patients’ depression treatment preferences and initiation, adherence, and outcome: a randomized primary care study. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:337–343. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.3.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hunot VM, Horne R, Leese MN, Churchill RC. A cohort study of adherence to antidepressants in primary care: the influence of antidepressant concerns and treatment preferences. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;9:91–99. doi: 10.4088/PCC.v09n0202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aveyard P, Begh R, Parsons A, West R. Brief opportunistic smoking cessation interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis to compare advice to quit and offer of assistance. Addiction. 2012;107:1066–1073. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hughes JR. Reduced smoking: an introduction and review of the evidence. Addiction. 2000;95(Suppl 1):S3–S7. doi: 10.1080/09652140032008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hughes JR, Carpenter MJ. The feasibility of smoking reduction: an update. Addiction. 2005;100:1074–1089. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01174.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Katz DA, Muehlenbruch DR, Brown RL, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Effectiveness of implementing the agency for healthcare research and quality smoking cessation clinical practice guideline: a randomized, controlled trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:594–603. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Joseph AM, Arikian NJ, An LC, Nugent SM, Sloan RJ, Pieper CF. Results of a randomized controlled trial of intervention to implement smoking guidelines in Veterans Affairs medical centers: increased use of medications without cessation benefit. Med Care. 2004;42:1100–1110. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200411000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sherman SE, Estrada M, Lanto AB, Farmer MM, Aldana I. Effectiveness of an on-call counselor at increasing smoking treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1125–1131. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0232-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Piper ME, Fiore MC, Smith SS, et al. Use of the vital sign stamp as a systematic screening tool to promote smoking cessation. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:716–722. doi: 10.4065/78.6.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Papadakis S, McDonald P, Mullen KA, Reid R, Skulsky K, Pipe A. Strategies to increase the delivery of smoking cessation treatments in primary care settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2010;51:199–213. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McIntosh S, Ossip-Klein DJ, Spada J, Burton K. Recruitment strategies and success in a multi-county smoking cessation study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2000;2:281–284. doi: 10.1080/14622200050147556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thompson RS, Michnich ME, Friedlander L, Gilson B, Grothaus LC, Storer B. Effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions integrated into primary care practice. Med Care. 1988;26:62–76. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198801000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McPhee SJ, Bird JA, Fordham D, Rodnick JE, Osborn EH. Promoting cancer prevention activities by primary care physicians. Results of a randomized, controlled trial. JAMA. 1991;266:538–544. doi: 10.1001/jama.1991.03470040102030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ockene JK. Primary care-based smoking interventions. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1(Suppl 2):S189–S193. doi: 10.1080/14622299050012051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Current estimates from the national health interview survey, 1993 (DHHS Publication No. 95-1518) Hyattsville, MD: Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control, National Center for Health Statistics; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2007. MMWR. 2008;57:1221–1226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rigotti NA. The future of tobacco treatment in the health care system. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:496–497. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-7-200904070-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Steinberg MB, Schmelzer AC, Richardson DL, Foulds J. The case for treating tobacco dependence as a chronic disease. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:554–556. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-7-200804010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]