Introduction

Most common sites for metastasis of rectum carcinoma are liver, lung, and peritoneum. Cutaneous and testicular metastasis from rectum is rare. Cutaneous metastasis from colorectal cancer occur less than 4%of patients [1]. The occurrence of cutaneous metastatic disease from colorectal cancer is uncommon and typically signifies widespread disease with poor prognosis [2].

Testicular metastases from colorectal cancers are rare. Metastatic carcinoma of testes are reported in 0.02 % to 2.5 % [3, 4]. Most common sites for primary are prostate [60 %], Melanoma [15 %], and sarcoma [10 %]. Rarely it metastasises from colon and rectum [5 %] [5].

Unusual site metastases of colorectal cancer are rarely detected in clinical practice. Here we report 4 patients of rectal malignancy having unusual site metastasis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Details of patients

| Serial no | Age (In year) | Sex | Stage of tumour | Treatment | Unusual site of metastasis | Site of accompanying metastasis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 40 | M | IV | CT | Skina | Liver |

| 2 | 56 | M | II | APR+CT | Skin | Liver |

| 3 | 43 | F | II | LAR+CT | Skin | – |

| 4 | 56 | M | IV | CT | Testesa | – |

aThese were initial presentation (Patients having occult primary)

CT chemotherapy, APR abdominoperineal resection, LAR low anterior resection

Case 1

In this case patient presented with chief complaint of skin nodules on chest and left side of neck since one month (Fig. 1). These swellings were mobile, firm, 1–2 cm in size. On histopathological examination Section showed stratified squamous epithelium infiltrated by malignant epithelial tumour cells dispersed in acini as well as tubules. Some of tumour cells show in intracytoplasmic mucin. Few signet ring cells were also evident. On IHC stainng-Primary panel of CK-7 and CK-20 was applied. Tumors showed positive for CK-20 and negative for CK-7and subsequently CDX 2 which was also positive. Thereby confirmed the diagnosis of metastasis from colorectal carcinoma. On further detail history there were altered bowel habit and weight loss but no history of rectal bleeding. Proctoscopic Examination showed a growth in lower rectum and guided biopsy showed infiltrating mucinous adenocarcinoma (signet ring type) of rectum. CECT abdomen showed single metastasis inside the liver. CECT chest was normal. Serum CEA level was 16 ug/L. Patient was on Chemotherapy (FOLFOX 4). Patient succumbed to death after 4 months from time of appearance of skin nodule.

Fig. 1.

Showing metastatic nodules on neck and chest

Case 2

This patient was diagnosed as a case of stage II rectal cancer. Abdominoperineal resection(APR) was done and was on adjuvant chemotherapy. Patient developed skin swellings at upper end of abdomen, chest and on neck after 10 month of surgery. On Excisional biopsy section showed skin lining infiltrated by tumour cells forming glands and acini lined by tumpur cells having high nucleo cytoplasmic ratio, vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli and moderate cytoplasm cytoplasm. Few mitotic figures also evident. On IHC staining it was positive for CK-20 and negative for CK-7 and subsequently CDX 2 was also positive. So Metastatic adenocarcinoma arising from colorectal carcinoma was confirmed. Patient died after 18 months of surgery and after 8 months from time of appearance of skin swellings.

Case 3

This patient was diagnosed as carcinoma mid rectum stage II. Guided biopsy report showed Mucinous Adenocarcinoma . Low anterior resection (LAR) was done. Patient was on chemotherapy. Patient developed swellings on chest after 8 months of surgery. It was mobile, Firm, 1–2 cm in size. Serum CEA level was 18 ug/L. Excisional biopsy of this swelling also showed Metastatic mucinous Adenocarcinoma, confirmed by IHC staining as in above cases. This patient died 15 months after surgery,7 months after appearance of skin nodules .

Case 4

In this patient (56 year/male) right testicular mass was presenting symptom and diagnosed as right testicular tumour (Fig. 2) so right sided high inguinal orchiectomy was done and biopsy report showed—“malignant epithelial tumour occasionally forming tubules. Tumour cells were floating in large mucin pools and infiltrating adjacent testicular parenchyma”. On IHC staining it was positive for CK-20 and negative for CK-7 and subsequently CDX 2 was also positive. Serum CEA level was 30 ug/L. Later on, on the basis of CECT(Abdomen and Pelvis, Fig. 3) and Proctoscopy guided biopsy Mucinos adenocarcinoma of rectum (Fig. 4) was diagnosed. Patient was on chemotherapy (FOLFOX 4). Pt died after 5.5 months after appearance of testicular swelling.

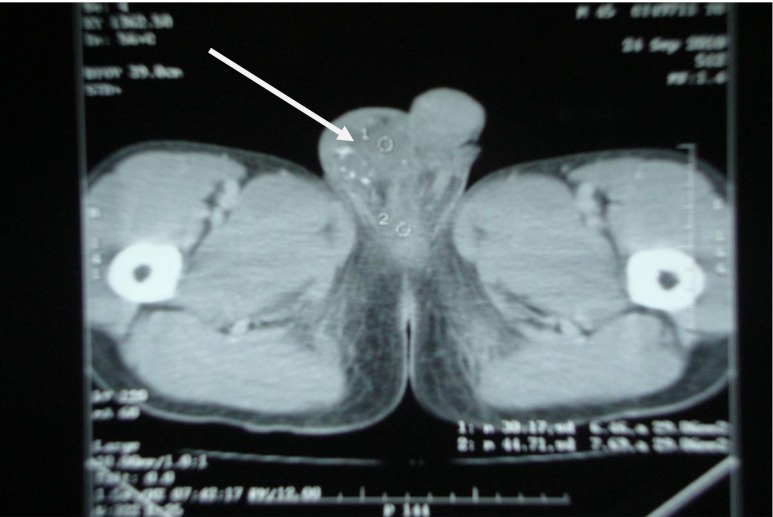

Fig. 2.

CECT Showing Right testicular mass

Fig. 3.

CECT Pelvis (after giving contrast per rectal) showing calcified Rectal mass

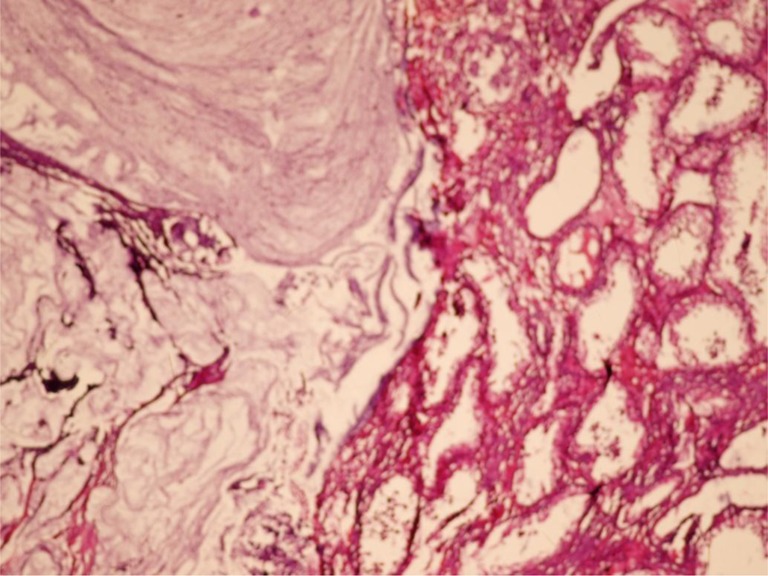

Fig. 4.

Showing metastatic tumour with extensive extracellular mucin and normal appearing testicular parenchyma

Result

Demographic and clinical presentation are shown in Table 1. Four patients of unusual site metastasis (Skin and testes) are reported. Of these four patients, in three patients skin metastasis and in one testicular metastasis were found. Mean age was 48.75 year. Three patients were male and one was female. Sites of unusual Metastasis in three patients were skin of neck, chest and abdomen around scar and in one patient in testes. Out of these three patients of skin metastastasis, two patients had accompanying liver metastasis. One patient presented as skin swelling and one patient presented as testicular swelling. In these two patients carcinoma rectum were occult. Both were diagnosed as metastatic adenocarcinoma rectum. In two patients Skin metastasis were found in postoperative follow up. In both R0 resection were performed. Mean survival age in both operated patients was 7.5 months from time of appearance of skin nodules and 16.5 months from date of surgery. Patient in which skin metastasis was initial presentation survived for 4 months only. Patient in which testicular swelling was main presenting complaint succumbed to death after 5.5 month from time of appearance of testicular swelling.

Discussion

Tumours most commonly presenting with skin metastases are breast cancer (69 %) in women and lung cancer (24 %) in men [1]. The occurrence of cutaneous metastatic disease from colorectal cancer is uncommon and typically signifies widespread disease with poor prognosis. Colorectal metastases usually occur within the first 3 years of follow up, and the median survival of patients after the appearance of cutaneous metastatic lesions is 18 to 20 months [2]. Krathen et al. reported the overall incidence of cutaneous metastases in various malignancies as 5.3 % and in colorectal cancer as less than 4 % in a met analysis of nine large scale studies assessing patients with cutaneous metastases [1]. In one study by Gazoni et al. Colorectal cancer was the third most common cause of cutaneous metastases in men behind melanoma and lung cancer and the seventh most common cause in women. Breast cancer and melanoma were the top two primary tumors in 70.7 % and 12.0 %, respectively of women with cutaneous metastases [6].

Cutaneous metastases are most commonly small 1 to 2 cm nodules that often coalesce and resemble epidermal cysts, keratoacanthomas, or pyogenic granulomas. This finding is characteristic of most cutaneous metastases regardless of the origin of the primary tumour. Ulceration occurs in approximately 10 % of nodules to the skin [6]. Skin involvement as the presenting sign of a silent internal malignancy is an even rarer event occurring in approximately 0.8 % [7]. The occurrence of cutaneous metastatic disease from colorectal cancer is uncommon and typically signifies widespread disease with poor prognosis. Colorectal metastases usually occur within the first 3 years of follow up, and the median survival of patients after the appearance of cutaneous metastatic lesions is 18 to 20 months [8, 9]. Colorectal cancers have potential for lymphatic and hematogenous metastases. Incidence of recurrence, both local and distant, remains significant. Distant metastases occur most often in the liver and lung; however, metastases to bone, adrenals, lymph nodes, brain, skin, pancreas and the oral region have been reported [10, 11].

In most case reports of metastatic colorectal cancer to the skin, the metastatic lesion was found after resection of the primary lesion. Dermal invasion, which is postulated to occur via intravascular and intralymphatic spread, usually occurs within 2 years of the primary resection and represents poor prognosis with mean survival ranging between 3 and 20 months [1]. For synchronous colorectal cancer patients, researchers usually found them more advanced in TNM stages and poorer prognosis, compared with their single lesion counterparts [12, 13]. Cutaneous metastases most often occur on a site relatively close to the internal primary organ. Skin metastases from the breast usually occur on the chest, the lung to the chest and upper extremities, and the gastrointestinal tract to the abdomen [14].

Although the exact mechanism of cutaneous metastases is not known, several routes of metastasis have been proposed for colorectal cancer. These are direct extension of the tumour, lymphatic spread, hematogenous spread, implantation during surgery, and spread along the embryonal remnants such as the urachus [15]. Most commonly, cutaneous metastases are detected on the previous incisions and at the umbilicus [16]. Powell et al. reported that 87 % of the umbilical metastases originates from internal malignancies [16]. In contrast to these findings, patients in the current study had cutaneous metastases outside the previous incisions and umbilicus which may support hematogenous spread in these cases.

The identification of cutaneous metastasis from a visceral malignancy is an ominous finding which usually signifies widespread disease and portends a poor prognosis [1, 9]. Lookingbill et al. [7] in a retrospective study of 4,020 patients found that after recognition of skin metastases, mean survival ranged from 1 to 34 months depending on the primary tumor. An average survival of 18 months was noted in patients with skin metastasis from colorectal carcinoma [7]. Schoenlaub et al. [17] retrospectively reviewed 200 cases of patients with evidence of cutaneous metastasis from a visceral primary and found the median survival to be 6.5 months. Patients with an underlying colorectal primary fared even worse with a median survival of 4.4 months [17].

Metastatic testicular cancers are rare and often found incidentally at autopsy or therapeutic orchiectomy. Testicular metastasis have been reported in 0.02 % to 2.5 % of orchidectomy specimens in two large autopsy series, which included non-neoplastic deaths [3]. Patel et al. reported metastasis in 3.6 % of 550 patients who had orchidectomy for testicular tumors, the common primary sites being prostate (60 %), followed by melanoma (15 %), sarcoma (10 %), lung, colon and renal cancer (5 % each) [5].

Lower temperatures in the scrotum creating an unfavourable environment for the seeding of the metastatic cells could explain the relative rarity of testicular metastasis. The routes of metastasis to the testis in solid tumours are thought to be retrograde arterial, venous or lymphatic embolization. Retrograde spread through spermatic veins from the renal veins or the retro peritoneum may be possible due to the absence of valves [18]. Hatoum et al. searched the English medical literature using the Medline/Pubmed database from 1950 through January 2010 and yielded 33 cases of testicular metastasis from rectal or colonic carcinoma [19].

Conclusion

Although local lymph nodes, liver, and lungs are the common and initial sites spread from colorectal carcinomas but distant site metastasis without symptoms of colorectal malignancy is unlikely but possible. Such vigilance may lead to early diagnosis of an underlying malignancy, which may lead to early intervention and better prognostication.

References

- 1.Krathen RA, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Cutaneous metastasis: a meta-analysis of data. South Med J. 2003;96:164–167. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000053676.73249.E5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Attili VS, Rama Chandra C, Dadhich HK, Sahoo TP, Anupama G, Babsy PP. Unusual metastasis in colorectal cancer. Indian J cancer. 2006;43(2):93–95. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.25891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dutt N, Bates AW, Baithun SI. Secondary neoplasms of the male genital tract with different patterns of involvement in adults and children. Histopathology. 2000;37:323–331. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2000.00983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gottlieb JA, Schermer DR. Cutaneous metastases from carcinoma of the colon. JAMA. 1970;213:2083. doi: 10.1001/jama.1970.03170380057025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel SR, Richardson RL, Kvols L. Metastatic cancer to the testes: a report of 20 cases and review of the literature. J Urol. 1989;142:1003–1005. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38969-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gazoni LM, Hedrick TL, Smith PW, Friel CM, et al. Cutaneous metastases in patients with rectal cancer: a report of six cases. Am Surg. 2008;74:138–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Sexton FM. Skin involvement as the presenting sign of internal carcinoma. A retrospective study of 7,316 cancer patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:19–26. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(90)70002-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarid D, Wigler N, Gutkin Z, Merimsky O, Leider-trejo L, Ron JK. Cutaneous and subcutaneous metastasis of rectal Cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2004;9(3):202–205. doi: 10.1007/s10147-004-0389-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adani GL, Marcello D, Anania G, et al. Subcutaneous right leg metastasis from rectal adenocarcinoma without visceral involvement. Chir Ital. 2001;53:405–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh T, Amritham U, Sateesh CT, et al. Floor of mouth metastasis in colorectal cancer. Ann Saudi Med. 2011;31(1):87–89. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.70583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Papadopoulos V, Michalopoulos A, Basdanis G, Papapolychroniadis K, Paramythiotis D, Fotiadis P, et al. Synchronous and metachronous colorectal carcinoma. Tech Coloproctol. 2004;8:S97–S100. doi: 10.1007/s10151-004-0124-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee CW, Wu RC, Hsu JT, et al. Isolated pancreatic metastasis from rectal cancer: a case report and review of literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2010;8:26. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-8-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oya M, Takahashi S, Okuyama T, Yamaguchi M, Ueda Y. Synchronous colorectal carcinoma: clinico-pathological features and prognosis. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2003;33:38–43. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyg010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brodland DG, Zitelli JA. Mechanisms of metastasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70146-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iwase K, Takenaka H, Oshima S, Kurozumi K, Nishimura Y, Yoshidome K, et al. The solitary cutaneous metastasis of asymptomatic colon cancer to an operative scar. Surg Today. 1993;23:164–166. doi: 10.1007/BF00311236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Powell FC, Cooper AJ, Massa MC, Goellner JR, Su WP. Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule: a clinical and histologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:610–615. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(84)80265-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schoenlaub P, Sarraux A, Grosshans E, Heid E, Cribier B. Survival after cutaneous metastasis: a study of 200 cases. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2001;128:1310–1315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salesi N, Fabi A, Di Cocco B, Marandino F, Pizzi G, Vecchione A, et al. Testis metastasis as an initial manifestation of an occult gastrointestinal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2004;24:1093–1096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hatoum HA, Abi Saad GS, Otrock ZK, Barada KA, Shamseddine AI. Metastasis of colorectal carcinoma to the testes: clinical presentation and possible pathways. Int J Clin Oncol. 2011;16:203–209. doi: 10.1007/s10147-010-0140-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]