Abstract

Primary splenic lymphomas (PSL) constitute a rare variety of splenic neoplasms. As a secondary lymphoid organ, the spleen is usually involved by lymphomas as part of the systemic illness. However, rarely it can be the exclusive site of disease burden. An elderly lady presented with symptoms and signs of splenomegaly. After evaluation she was found to have a splenic tumor. Splenectomy was done which revealed primary splenic lymphoma. This case report highlights the evaluation and management of this illness.

Keywords: Primary splenic lymphomas, Splenomegaly, Splenectomy

Introduction

Primary Splenic Lymphomas (PSL) are also known as Primary Malignant Lymphomas of the Spleen (PMLS) [1].They comprise 2 % of all Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas [1]. Most of the splenic lymphomas are of B cell origin [1]. Diffuse Large B cell Lymphomas (DLBCL), which can present extra-nodally in more than 40 % of cases often occur in the spleen [2] primarily with the incidence being 22.4–33.3 % [3].

Case Details

A 50 year old female with no comorbidities presented with history of pain abdomen since 2 months, situated in the left upper abdomen which was a dragging type of pain. There was also history of fever on and off since the last 2 months without chills and rigors. There was no history of weight loss, loss of appetite, vomiting, bleeding episodes, bony pains, and melena.

Examination revealed splenomegaly 5 cm below the left costal margin. There was no evidence of hepatomegaly or free fluid in the abdomen. Systemic examination was unremarkable except for anemia. There was no generalized lymphadenopathy.

Basic blood investigations revealed microcytic hypochromic anemia with normal leucocyte and platelet counts. Coagulation profile and serum chemistries were also within normal limits. Viral markers were negative. Ultrasound showed a large solid mass lesion in the gastro splenic region that was probably arising from the tail of the pancreas or the spleen. CT scan showed a large solid mass arising from the lower pole of the spleen measuring 7.5 × 6 cm suggestive of malignant lesion of the spleen probably Angiosarcoma or Lymphoma of the spleen. Bone marrow examination and chest radiographs (done to rule out systemic involvement by lymphoma) were normal.

Thus a diagnosis of primary tumour of the spleen was made and patient was posted for surgery.

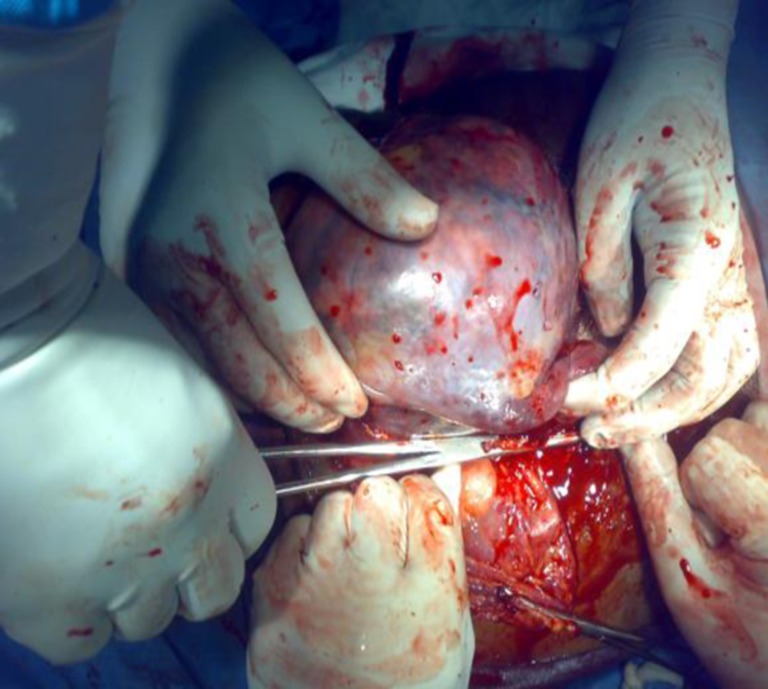

The patient underwent open splenectomy via a midline approach. Intra-operatively, there was asymmetrical splenic enlargement with a large mass arising from the lower pole of the spleen (Fig. 1). Liver was normal. There was no evidence of retroperitoneal or mesenteric lymphadenopathy. However a few nodes at the splenic hilum were enlarged (Fig. 2). Omental and sub-diaphragmatic adhesions to the spleen was noted which were carefully separated. Adhesions were also noted to the fundus of stomach which was carefully released. Splenectomy was done. Hemostasis was achieved and abdomen closed in layers.

Fig. 1.

Tumor at the lower pole of spleen

Fig. 2.

Ligation of splenic hilum

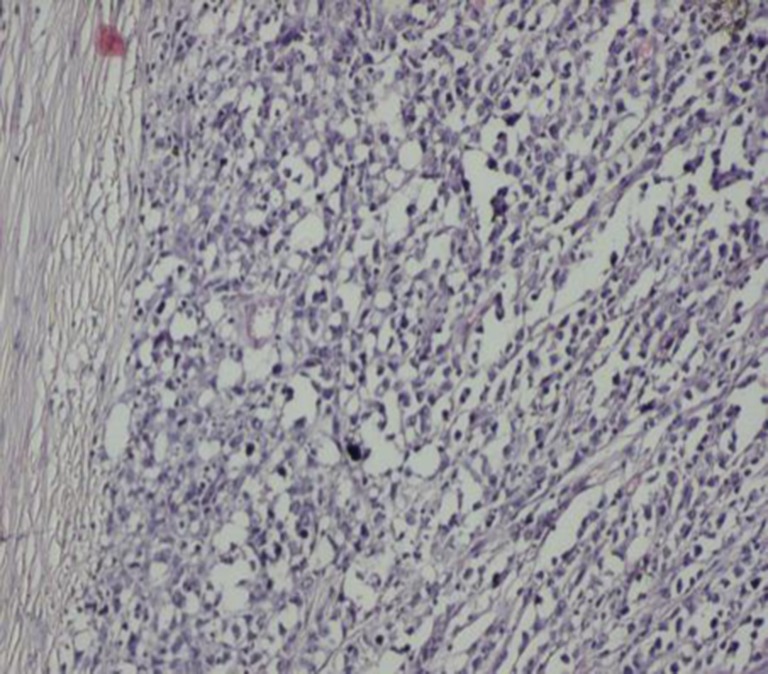

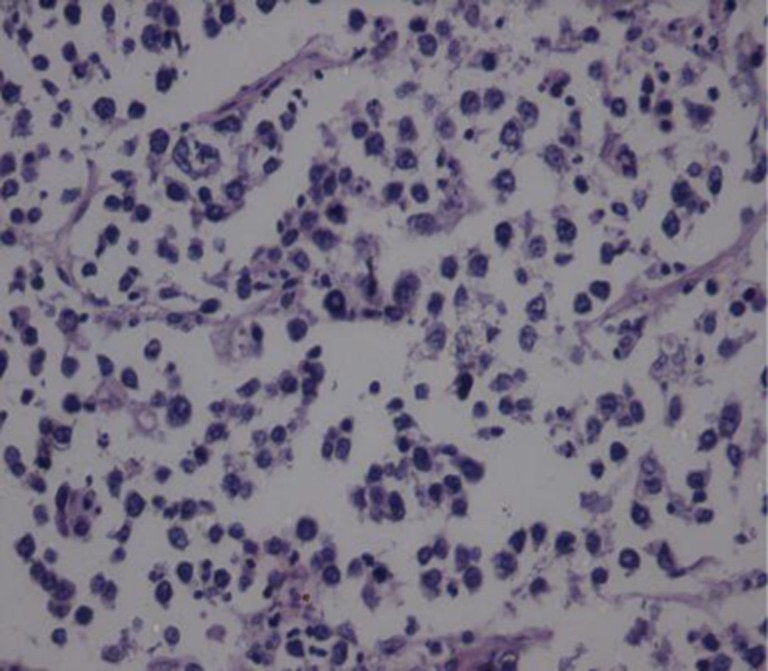

Gross examination of the specimen showed a grey white mass in its lower pole (Fig. 3). Histopathological examination made a diagnosis of Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma of the spleen probably of B cell origin (Figs. 4 and 5).

Fig. 3.

Cut section showing grey-white fleshy tumor

Fig. 4.

Low power view showing sheets of tumor cells

Fig. 5.

High power view showing monotonous tumor cells

Immunohistochemical studies showed positivity for LCA (leukocyte common antigen) [++++], CD 20 [+++] and CD 10 [+] with negativity to CD 30, CD 5 and Cytokeratin (CK) favoring a diagnosis of Diffuse large B cell Lymphoma of Spleen.

The patient is currently undergoing chemotherapy with CHOP regimen and is found to be symptom free on follow up.

Analysis

PMLS (or PSL) is a rare disorder with an incidence of <1 % [3]. Primary splenic lymphoma has been described both in context of Hodgkin’s and Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The Non-Hodgkin’s type consists of an extra-nodal biologically virulent cancer [4].

PSL has been defined in a number of ways. Das Gupta et al [5]. defined PSL as a lymphoma involving only the spleen and the splenic hilar lymph nodes; the diagnosis of PSL being made if isolated splenomegaly occurs in the absence of any other localized tumors, particularly in the liver or the para-aortic or mesenteric lymph nodes. Before confirming the diagnosis of PSL, a 6-month relapse-free period should exist after removal of the spleen. Skarin et al [6]. suggested that the diagnosis of PSL can be made if splenomegaly is a predominant feature in any lymphoma involving the spleen. Kraemer et al [7]. reserved the diagnosis of PSL for patients with splenomegaly, cytopenia of at least two hematologic cell lines and the absence of peripheral adenopathy. Kehoe et al [8]. defined PSL as NHL arising primarily in the spleen or as NHL principally confined to the spleen and its local lymph nodes. In this report, the entity fits into the definitions given by Skarin et al. and Kehoe et al.

These patients usually present with low grade fever, night sweats and symptoms related to splenomegaly that includes left upper quadrant pain. In some cases, the patients present as pyrexia of unknown origin (PUO) [1].There may be other specific symptoms resulting from direct invasion of the pancreas, stomach, diaphragm, colon or greater omentum [9] including tumor fistulization or rupture. Organ size should not be used to assess splenic involvement in patients with lymphoma, since the spleen can be normal in size despite tumor infiltration [10]. There are various clinical presentations described:

Asymptomatic patients with isolated splenomegaly

Patients in whom splenomegaly is associated with blood count variations

Constitutional symptoms with abdominal pain secondary to splenomegaly.

In our report, the patient was symptomatic at presentation.

Ahmann [11] classified the gross appearance of PSL into four categories namely homogenous enlargement without masses, miliary masses, 2–10 cm neoplasms and large solitary tumors [4]. In our case, there was a large solitary tumor occupying almost 3/4th of the spleen.

The most common histological subtypes (seen in more than 50 % of cases) is that of low-grade lymphocytic lymphoma (well differentiated small cell variant or with lymphoplasmocytic/ lymphoplasmocytoid differentiation) or intermediate-grade lymphoma (diffuse or nodular mantle-zone lymphoma) [12].

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) of spleen accounts for about 1/3 of all primary splenic lymphomas [13]. DLBCL of spleen usually presents as single or multiple confluent nodules with majority being derived from the white pulp [2] and is considered an aggressive neoplasm. The common age of occurrence is in the sixth and seventh decade. There is usually a single tumor mass, which is large and occupies more than 50 % of the spleen; this pattern however, is not specific to primary DLBCL as secondary involvement by DLBCL will have the same pattern. Bone marrow involvement is usually negative at the time of presentation [13].

The most common laboratory finding seen in these patients is anemia along with increased ESR and increased LDH levels.

On imaging, DLBCL manifests as splenomegaly associated with a well-defined hypoechoic mass [14]. Although majority of them are hypoechoic, rare echogenic lesions or bright echoes due to calcifications or gas may be detected. Anechoic areas generally suggest liquefactive necrosis and in the presence of fever, it may be difficult to distinguish from splenic abscess [4]. Rim enhancement may rarely be encountered indicating pseudocapsule formation or adjacent compressed parenchyma [4].

Post-treatment differentiation of residual disease or relapse from either fibrosis or necrosis can be accomplished using whole body F-deoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) [4]. Malignant diseases most commonly involving the spleen are principally F18-FDG avid diseases, including lymphoma and metastases from malignant melanoma, lung cancer, ovarian cancer, and gastrointestinal malignancies. In contrast, the common benign splenic lesions, hemangiomas and hamartomas are not expected to show increased F18-FDG uptake. F18-FDG PET/CT can also identify additional unsuspected sites of disease, which may be more accessible for biopsy. This may obviate the need to biopsy the spleen itself [15]. FDG PET/CT has an accuracy of almost 100 % in diagnosing primary splenic involvement during initial staging whereas CT alone has an overall accuracy of 57 % [10].

FNA biopsy of the spleen, although not widely accepted, is gaining renewed interest. Core biopsy, obtained with a 21 or 22 gauge needle or even laparoscopically, has also been used successfully for histological identification of PSL subtype [4]. Ultrasound (US) guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy or cytologic examination has been shown to be useful in the diagnosis of splenic involvement by lymphoma. In the spleen, however, malignant lymphocytes obtained in this manner can be distinguished from normal lymphocytes only with difficulty, and histologic confirmation may be required. This is possible using US-guided tissue core biopsies that allow histologic and immunologic classification [16].

Ahmann et al [11]. grouped PSL into three stages depending on the extent of the disease determined either at surgery or by other studies in the immediate postoperative period.1 Stage I refers to those patients with tumor is limited to the spleen only. Stage II patients have involvement of the nodes in the splenic hilum, while stage III patients have involvement of the liver or lymph nodes beyond the splenic hilum. In our case, the patient belonged to stage II.

The treatment of choice in majority of these isolated splenic lymphomas is splenectomy. Splenectomy has been proposed as a therapeutic intervention, with acceptable morbidity and mortality rates. Besides, operation induces significant reversal of hematological abnormalities and once the hematological response is achieved, results appear to be sustained for several months, permitting systemic chemotherapy if necessary. In addition, splenectomy may introduce a prolonged period of disease control and nodal regression, followed by significant favourable survival. Early splenectomy eliminates the possibility of local relapse and prevents continuous neoplastic dissemination from the primary site [4].

Chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy after splenectomy prolongs survival of PSL [9]. Splenic irradiation is preferred in cases of inoperable neoplasms leading to temporary shrinkage of the spleen and progressive reduction of its size [4].

DLBCL requires CHOP regimen in the adjuvant setting [17].

The important prognostic factors include the stage of disease at presentation and the tumor type with DLBCL having a more aggressive course. Also, failure to correct thrombocytopenia after splenectomy is a poor prognostic factor [9].

Conclusions

PMLS is a rare disease. Splenectomy is often required for diagnosis. Prognosis is favorable if the disease is confined to the spleen. Post-operative adjuvant treatment is necessary in most cases.

References

- 1.Doshi K, Stanciu J, Cerevantis J, et al. Splenic Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma presenting as recurrent kidney stones-an incidentaloma. Proc West Pharmacol Soc. 2008;51:55–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kashimura M, Naro M, Akikusa B, et al. Primary splenic DLBCL manifesting in red pulp. Virchows Arch. 2008;453:501–509. doi: 10.1007/s00428-008-0673-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu CM, Cheng LC, Lo GH, et al. Malignant lymphoma of spleen presenting as acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(17):3773–75. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i27.3773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Konstantiadou I, Mastoraki A, Papanikolaou I, Sakorafas G, Safioleas M. Surgical approach of primary splenic lymphoma: Report of a case and review of literature. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2009;25(3):120–124. doi: 10.1007/s12288-009-0025-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dasgupta T, Coombes BC, Brasfield RD. Primary malignant neoplasms of the spleen. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1965;120:947–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skarin AT, Davey FR, Moloney WC. Lymphosarcoma of the spleen. Arch Intern Med. 1971;127:259–65. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1971.00310140087011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kraemer BB, Osborne BM, Butler JJ. Primary splenic presentation of malignant lymphoma and related disorders- a study of 49 cases. Cancer. 1984;54:1606–19. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19841015)54:8<1606::AID-CNCR2820540823>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kehoe J, Straus DJ. Primary lymphoma of the spleen: Clinical features and outcome after splenectomy. Cancer. 1988;62:1434–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19881001)62:7<1433::AID-CNCR2820620731>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim JK, Hahn JS, Kim GE, Yang WI. Three cases of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma presenting as primary splenic lymphoma. Yonsei Medical Journal. 2005;46(5):703–709. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2005.46.5.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paes F, Kalkanis D, Sideras P, Serafini A. FDG PET/CT of extra-nodal involvement in Non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Hodgkin disease. RadioGraphics. 2010;30:269–291. doi: 10.1148/rg.301095088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmann DL, Kiely JM, Harrison EG, Payne WS. Malignant lymphoma of the spleen. Cancer. 1966;19:461–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196604)19:4<461::AID-CNCR2820190402>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gobbi P, Grignani G, Pozzetti U, Bertoloni D, Pieresca C, Montagna G, et al. Primary splenic lymphoma: Does it exist? Haematologica. 1994;79:286–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Torlakovic E: Bone Marrow Workshop Prague 2012

- 14.VanVliet J. Primary DLBCL spleen. Journal of Diagnostic Medical Sonography. 2010;26(3):147–149. doi: 10.1177/8756479310368431. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Metser U, Miller E, Kessler A, Lerman H, Lievshitz G, Oren R, et al. Solid splenic masses: Evaluation with F18-FDG PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2005;46(1):52–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cavanna L, Artioli F, Vallisa D, Donato C, Bertè R, Carapezzi C, et al. Primary lymphoma of the spleen: Report of a case with diagnosis by fine-needle guided biopsy. Haematologica. 1995;80:241–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iannitto E, Tripodo C. How I diagnose and treat splenic lymphomas. Blood. 2011;117(9):2585–95. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-271437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]