Abstract

Background

This study examined the interaction between restraint stress and ethanol drinking in mice that consume low and high amounts of ethanol.

Methods

Two strains of mice (129SVEV and C57BL/6J) underwent 1 hour of restraint stress twice per day for 4 days in the presence of a CRF-1 receptor antagonist, a glucocorticoid receptor antagonist or vehicle. Ethanol preference and consumption were assessed using a two bottle choice design. In another study, mice were implanted with pellets containing corticosterone; ethanol preference and consumption were assessed using a two bottle choice design.

Results

Restraint stress significantly increased ethanol preference and consumption in 129SVEV mice but not in C57BL/6J mice. Then 129SVEV mice underwent the identical stress procedure; however, mice received either the CRF-1 receptor antagonist, R121919 (15 or 20 mg/kg, ip) or vehicle 30 minutes prior to stress. R121919 did not block the stress-induced change in ethanol preference despite causing a significant blunting in the HPA axis. Negative results were also obtained using the CRF-1 receptor antagonist, Antalarmin (20 mg/kg, ip). In another study, 129SVEV mice were administered either the glucocorticoid receptor antagonist Mifepristone (25, 50 or 100 µg/kg, ip) or vehicle under the same procedure. Mifepristone did not alter ethanol preference. Moreover, the three receptor antagonist did not alter nonstress ethanol consumption either. In the last study, both mouse strains underwent active or sham adrenalectomy, then pellets containing corticosterone or placebo were implanted and preference for ethanol versus water was tested. Corticosterone administration decreased ethanol consumption in a strain-dependent manner.

Conclusion

These data show the restraint model for stress can modestly increase ethanol consumption in 129SVEV mice but not in C57BL/6J mice. Pharmacologic manipulation of CRF and corticosterone did not blunt baseline or stress-induced change in ethanol preference nor did administration of corticosterone mimic the effects of restraint stress on ethanol consumption. These findings suggest the mechanism responsible for increasing ethanol consumption in this model is independent of the HPA axis and extra-hypothalamic CRF.

Keywords: Ethanol Preference, Restraint Stress, CRF-1 Receptor, Glucocorticoids Receptor, Antagonist

Addiction to ethanol or other drugs of abuse is a complex phenomenon influenced by genetic and environmental determinants. Clinical investigation has confirmed the popular belief that stress contributes to the development, maintenance, and outcome of substance use disorders in humans (Karlsgodt et al., 2003; Sussman and Dent, 2000). Moreover, in humans, stress has been implicated as an important precipitant of relapse (Breese et al., 2005; Sinha, 2001). Findings from human laboratory studies have further shown that stress increases drug craving (Sinha et al., 2003). Alcoholics experiencing highly threatening or chronic psychosocial stress following treatment are more likely to relapse than abstaining individuals not experiencing such stress (Noone et al., 1999).

The stress response is the product of at least three components: First is the glucocorticoid response to stress mediated through the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Stress provokes CRF release from the hypothalamus, which in turn, stimulates pituitary ACTH secretion. Subsequently, ACTH induces adrenal secretion of glucocorticoids, specifically corticosterone in rodents and Cortisol in humans. The magnitude of the Cortisol response to stress is regulated by the interaction of environmental and genetic determinants (Federenko et al., 2004). Second, stress activates the sympathetic nervous system resulting in the release of norepinephrine and epinephrine. Third, stress activates extra-hypothalamic CRF in the amygdala and other brain regions that can modulate both the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympathetic nervous system.

A variety of procedures have been used to explore the effect of various stress paradigms on ethanol self-administration in rodents. These include spontaneous drinking paradigms (24-hour access or 2-hour limited access) and operant schedules (Roberts et al., 1996; Samson, 1986; Samson et al., 1989). The most robust and consistent models showing stress induction of ethanol consumption are based on procedures employing animals in ethanol withdrawal or abstinence states (e.g., reinstatement or ethanol deprivation effect (Breese et al., 2005, 2004; Funk et al., 2004; Lé and Shaham, 2002; Liu and Cull-Candy, 2002; O’Dell et al., 2004; Roberts et al., 1996, 2000). Thus, the ethanol deprivation and withdrawal models provide useful substrates to identify neural circuitry mediating the interactions of stress and abstinence in precipitating relapse. While these models generate important information on how stress, anxiety, and withdrawal may precipitate relapse in abstinent alcohol-dependent persons, they do not provide a model for how stress interacts with ongoing social ethanol consumption to trigger increased intake (e.g., self-medicating behavior), thereby increasing initial susceptibility to alcohol use disorders.

Studies examining the effects of other types of stress on ethanol consumption, and which probably induce different stress mechanisms compared to ethanol deprivation, have produced less consistent results. For example, Spanagel and co-workers showed that swim stress increased ethanol consumption in unselected Wistar rats whereas foot shock increased ethanol consumption in Wistars, ethanol preferring rats (P), high ethanol drinking (HAD) rats, and Alko alcohol (AA) rats (Vengeliene et al., 2003). However, another recent paper reported that chronic, unpredictable restraint stress actually reduced voluntary ethanol drinking in P rats and the high ethanol drinking rats during the application of stress (Chester et al., 2004).

Given this background, we sought to work with a model which could escalate ethanol consumption similar to how stress may increase ethanol intake in a social drinker rather than in a recently abstinent alcohol-dependent person. To this end, we employed a well-known restraint model of stress to compare ethanol consumption and preference in ethanol non-preferring and ethanol-preferring strains of mice with only limited previous ethanol exposure. The goal was to determine if the model could invoke a mild to moderate increase in ethanol preference and consumption mimicking individuals who escalate their ethanol consumption to reduce anxiety during stressful situations (e.g., self-medicating behavior). Our intention was not to create a model that mimics heavy ethanol consumption observed in ethanol-dependent persons. In the second part of the study, we employed pharmacological manipulation of CRF and corticosterone to attenuate HPA axis responses to restraint stress in order to determine if this would reverse the effects of stress on ethanol consumption. Finally, we treated mice with glucocorticoids to determine if this would alter ethanol consumption and preference independent of CRF.

METHODS

Subjects

Male 129SVEV mice (Taconic Lab) and C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Lab), age 8 to 10 weeks old. We chose 129SVEV mice as a low ethanol drinking strain to compare with C57BL/6J mice because under baseline conditions 129SVEV mice drink a modest amount of ethanol as opposed to a strain like DBA which generally avoid ethanol. This choice was based on our aim which was to see if the stress model could increase ethanol intake in a strain of mouse that was not aversive to ethanol but did not display ethanol preference either. This was performed to try to mimic the social drinker. The C57BL/6J mice were selected for study because they tend to be ethanol preferring.

Mice were randomly assigned to experimental groups. The number of mice for each group is presented in the results and figure legends. They were housed in a constant 12 hours light/dark cycle with free access to laboratory rodent chow at all times in Johns Hopkins University Animal Facility. All procedures are approved by IACUC.

Drugs

R121919, 3-[6-(dimemylammo)-4-memyl-pyrid-3-yl]-2,5-dimethyl-N,N-dipropyl-pyrazolo[2,3-a]pyrimidin-7-amine; Ki = 3.5; cLog p = 4.8), was dissolved in 0.1 N hydrochloric acid and vortexed thoroughly before addition of dH2O to make a 20 mg/ml final solution. The vehicle was made as above with the omission of R121919. R121919 was synthesized by Dr. Kenner Rice at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) (Laboratory of Medicinal Chemistry).

The CRF-1 receptor antagonist Antalarmin (N-butyl-N-ethyl-[2,5,6,-trimethyl-7-(2,4,6-trimethylphenyl)-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin4-yl]-amine; Ki = 1.0; cLog p = 7.0), was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich Company and dissolved as follows: Antalarmin was added to 150 µl ethanol, heated at 65°C for 5 minutes; 150 µl of Cremophor EL was added and heated again at 65°C for 5 minutes. Then 1.2 ml dH2O (65°C) was added to make a final 20 mg/ml solution (mice received <1.6 mg/kg ethanol). The vehicle was made as above with the omission of Antalarmin.

R121919 and Antalarmin cross the blood–brain barrier and block both the peripheral and central effects of CRF (Zorrilla and Koob, 2004). Pharmacologically significant brain and plasma levels of Antalarmin (Zorrilla et al., 2002) and R121919 (Chen et al., 2004) have been reported following doses used in this study. Receptor occupancy data for R121919 have also been reported (Heinrichs et al., 2002).

Mifepristone is an 11-dimethyl-amino-phenyl derivative of nor-ethindrone. It has a high affinity for cytosolic type II glucocorticoid receptors in various target tissues, but exhibits little agonist activity (Mao et al., 1992). The concentration of Mifepristone reaches its peak at 1.3 hours after administration and its half-life is approximately 18 hours. Mifepristone was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich Company. It was dissolved in ethanol first, then Cremophor EL, and dH2O were added to make a 1 mg/mL in final 0.2% ethanol (mice received less than 1.6 mg/kg) and 0.2% Cremophor EL solution. Vehicle was made as above with the omission of Mifepristone. All drugs were administered intraperitoneally (IP) at 1 mL/kg.

Ethanol was purchased through Sigma and dissolved in dH2O to make 3, 6, and 12% solutions (v/v).

Ethanol Preference and Stress Paradigm

Mice were housed individually and allowed equal access to two drinking bottles containing water or different concentrations of ethanol mixed in water to increasing concentrations of ethanol starting with 3% ethanol (v/v) versus water for 2 days, 6% ethanol and water for 2 days and finally 12% ethanol versus water for 7 days. All experiments were conducted during the last 7 days when mice had access to 12% ethanol and water. Measurement of fluid intake began during the pre-stress period designated as days 1 to 3 when mice had access to the 12% ethanol solution and water. The restraint stress procedure was conducted on days 4 to 7. Each mouse was placed in a DecapiCone restrainer twice per day for 60 minutes, between 9 and 10 am and again in the afternoon between 3 and 4 pm. The control group remained in their home cage without perturbations. Control and stressed mice had free access to water and 12% ethanol at all times except during the restraint period. There was 24 hours access to ethanol and water consumption which was recorded daily. Bottle positions were switched every day to control for side preference. Body weight and food consumption were measured at the first day and last day of experiments. Data are presented as ethanol preference defined as volume of ethanol consumption divided by total fluid volume consumed (ethanol + water) and actual ethanol intake expressed as ethanol consumption (g/kg).

Tail blood was collected daily immediately before the morning session and after the afternoon restraint stress sessions for corticosterone measurement or as indicated.

Stress and Antagonist Treatment

For the CRF receptor 1 antagonist experiment, mice underwent the drinking paradigm and restraint stress procedures as described above.

During the restraint stress days 4 to 7, R121919 (15 mg/kg or 20 mg/kg), Antalarmin (20 mg/kg) or vehicles were administered to mice 30 minutes prior to the morning and afternoon restraint stress sessions. Pre-stress fluid consumption was measured over 3 days and is expressed as the mean (SEM) of days 1 to 3. Stress fluid consumption was measured during days 4 to 7 and is expressed as the mean (SEM) for this time period.

For the glucocorticoid receptor antagonist experiment, mice underwent the drinking paradigm and restraint stress procedures as described above. During the restraint stress days 4 to 7, mice were pretreated with 3 doses of Mifepristone (25, 50, and 100 µg/kg) or vehicle, 5 minutes prior to the start of the morning stress session. The 100 µg/kg dose or twice a day dosing of lower doses of the antagonist resulted in animal death or severe illness. Only data for the 25 and 50 µg/kg doses are shown. Pre-stress fluid consumption was measured over 3 days and is expressed as the mean (SEM) of days 1 to 3. Stress fluid consumption was measured during days 4 to 7 and is expressed as the mean (SEM) for this time period.

Tail blood was collected daily immediately before the morning session and after the afternoon restraint stress sessions for corticosterone measurement or as indicated.

Nonstress and Antagonist Treatment

The effects of the three antagonist were also studied under basal or nonstressed conditions. Mice received incremental increases in ethanol solutions until drinking was stabilized on a 12% solution as described above for the stress session. Mice were then divided into vehicle and treatment groups, and injections were administered over the following four days. During the 4-day treatment, R121919 (20 mg/kg), Antalarmin (20 mg/kg) or the appropriate vehicle were administered to mice twice per day in the morning and afternoon. The glucocorticoid receptor antagonist experiment was conducted in the identical manner except Mifepristone (50 µg/kg) or vehicle, were given once per day in the morning. Treatment fluid consumption is expressed as the mean (SEM) for this time period.

Corticosterone Replacement

Mice were weighed and anesthetized with Pentobarbital (30 mg/kg ip). Flank incisions were made; once identified, the adrenal glands, together with the periadrenal fat were removed. In sham-operated mice, adrenal glands were exposed, but left intact. Adrenalectomized mice were maintained with 0.9% saline, and 48 hours later pellets containing 10 mg concentration of corticosterone (purchased from Innovating Research of America) or placebo were implanted. Sham-operated mice were implanted with placebo pellets. Following 5 days of recovery, mice were given access to incremental concentrations of ethanol starting with 3% ethanol (v/v) versus water for 2 days, 6% ethanol and water for 2 days and finally 12% ethanol versus water for 3 days. Bottle positions were switched every day to avoid side preference. Ethanol and water consumption were recorded daily. Data are presented as mean (SEM) of the final 3 days during which mice had access to 12% ethanol or water. Body weight and food consumption were measured at the first day and last day of experiments.

Two Hours Limited Access to Ethanol

Another group of mice were housed individually and allowed equal access to two feeding bottles containing water or ethanol using the same incremental ethanol concentration procedure as mentioned above. On the morning of experiment day, mice either underwent the 60 minutes restraint stress procedure (n = 8) or were not stressed (n = 10) and then placed back into cages with two feeding bottles containing water and 12% ethanol. Two hours later, ethanol and water consumption were recorded and tail blood was taken for blood ethanol levels. The same procedure was repeated again following the afternoon stress period.

Assays

The same mice were employed to determine plasma corticosterone levels and ethanol intake. Mice used for the corticosterone measurements were given access to ethanol during the pre-stress period. Tail blood was collected in heparinized tubes and separated by centrifugation for 15 minutes at 13,000 rpm (15,700 × g). The plasma was stored at −20°C until corticosterone was measured with radioimmunoassay (ICN Biomedicals, Inc.) and ethanol levels by the Analox method (Lunenburg, MA). Inter- and intra-assay coefficient of variation was < 10% for both assays.

Statistical Analyses

Corticosterone levels prior to and following stress or drug treatment were compared using a analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures of the session (pre-stress vs. poststress) versus mouse strain (129SVEV mice vs. C57BL/6J mice), with the Wilks’ Lambda probability of chance findings ≤0.05 interpreted as significant. For ethanol preference, ethanol consumption, and total fluid consumption, pre-stress values were obtained by calculating the mean of these variables across the 3 pre-stress days, and post-stress values were obtained by calculating the mean of the 4 post-stress days. Subjects’ mean pre-stress and mean poststress values of these variables were entered as dependent variables into MA-NOVA of the group (treatment vs. no treatment) versus session (pre-stress vs. poststress) versus mouse strain (129SVEV mice vs. C57BL/6J mice), with probability of chance findings ≤0.05 interpreted as significant. Significant group × session × genotype interactions prompted post hoc tests to compare individual data points.

RESULTS

Stability of Alcohol Preference Over Time

Figure 1 shows daily ethanol preference scores during the “pre-stress” and “stress” period for 129SVEV and C57BL/6J mice. In the 129SVEV mice (Fig. 1 A), preference and consumption (not shown) were stable in the nonstress group over the entire 7-days. There was also a significant time x group interaction indicating that ethanol preference was significantly increased in the stress group but not in the control group over the 7-day period of observation (F(l,74) = 19.365, p < 0.001). Notice that the 129SVEV did not desensitize to the repeated sessions of stress. In the C57BL/6J mice (Fig. 1 B), preference and consumption were also stable in the nonstress group over the 7-day period of observation. In contrast to the 129SVEV mice, alcohol preference in C57BL/6J mice was not altered by the stress procedure. For all subsequent alcohol intake figures, pre-stress fluid consumption, measured over 3 days, is expressed as the mean (SEM) of days 1 to 3. Stress fluid consumption, measured during days 4–7, is expressed as the mean (SEM) for this time period.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of 12% ethanol preference before and during stress in 129SVEV mice and C57BL/6J. (A) 129SVEV mice. Ethanol versus water preference. Post hoc significance levels. *Denotes significance compared to control; p < 0.001. **Denotes significance compared to control; p = 0.005. ***Denotes significance compared to control; p = 0.006. (B) C57BL/6J. Ethanol versus water preference.

Corticosterone and Ethanol Responses to Restraint Stress

The corticosterone response to the restraint stress procedure was compared in 129SVEV (n = 32) and C57BL/6J (n = 7) mice. Blood for plasma corticosterone measurement was collected immediately before and after the restraint stress on day one of the stress procedure. Prior to the stress procedure, corticosterone levels did not differ between strains (Fig. 2). Restraint stress significantly increased corticosterone levels compared to the pre-stress period in both strains of mice (main effect of session: F(l,37) = 425.37, p < 0.001), with 129SVEV mice demonstrating higher corticosterone levels following the stress procedure than C57BL/6J mice (session X mouse strain interaction: F(1,37) = 13.19, p = 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Plasma corticosterone levels before and immediately following the restraint stress procedure in 129SVEV (n = 32) and C57BL/6J (n = 7) mice. *Denotes significance compared to “pre-stress” groups; p < 0.001. +Denotes significance compared to poststress C57BL/6J; p = 0.001.

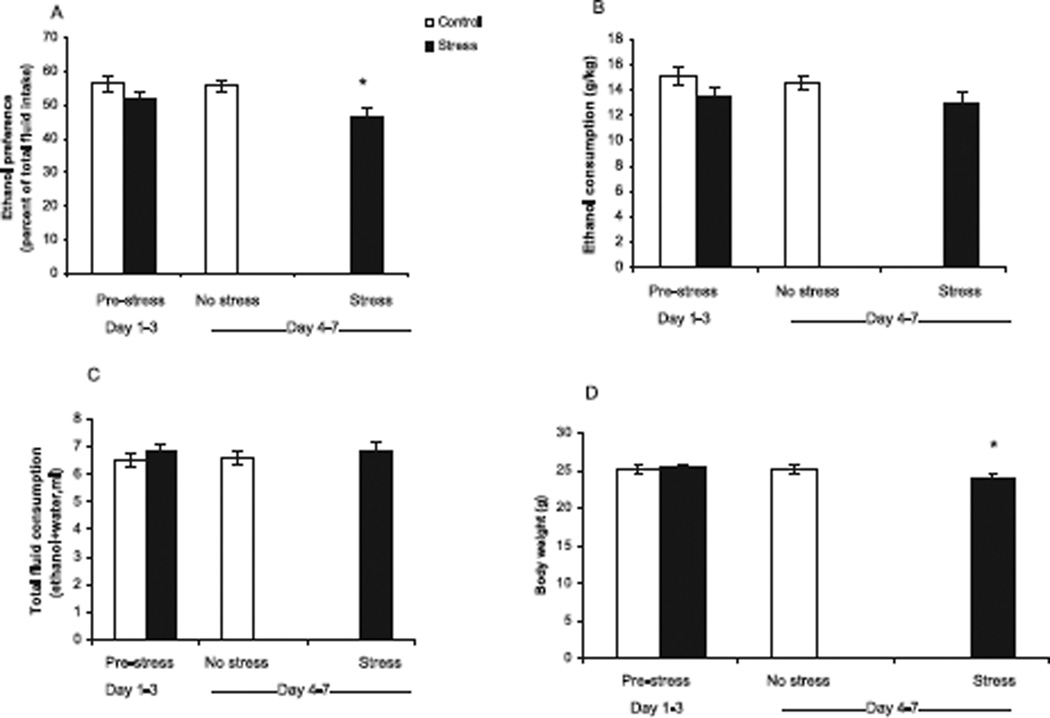

To more thoroughly test the hypothesis that the restraint stress procedure would increase ethanol consumption, 47 129SVEV mice and 15 C57BL/6J mice underwent the restraint stress protocol whereas 40 129SVEV mice and 15 C57BL/6J mice served as control as described in the methods. Ethanol Intake was stable over 3 days of baseline measurements in the “stress” group and over 7 days of measurement in the “nonstress” group. Both before and after stress, ethanol preference was greater in the C57BL/6J mice (51% ± 4 in the stress group and 58% ± 4 in the control group) compared to the 129SVEV mice (26% ± 0.9 in the stress group and 28% ± 1.2 in the control group; main effect of mouse strain: F(1,114) = 190.28, p < 001), consistent with the 129SVEV mice being non-ethanol preferring. The C57BL/6 mice had ethanol preference scores ranging from 49 to 57% compared to the 129SVEV mice, which ranged between 25 and 31%. Although the C57BL/6 mice had reduced ethanol preference scores than previously reported, there was no overlap between the two groups. Within strains, the control and stress groups did not differ on any measure during the pre-stress period. Compared to ethanol preference during the pre-stress period, ethanol preference was significantly increased in the stress group but not in the nonstressed, control group (main effect of group: F(1,114) = 9.52, p = 0.003). However, this finding was due to an increase in ethanol preference in the 129SVEV mice; ethanol preference in the C57BL/6J mice did not change following stress (Figs 3A and 4A). Similarly, ethanol consumption increased in the stress group but not in the control group (main effect of group: F(1,111) = 5.06, p = 0.026. As with ethanol preference, this finding was accounted for by the 129SVEV mice, whose ethanol consumption increased following stress, whereas there was no change in ethanol consumption in the C57BL/6J strain (Figs 3B and 4B). Total fluid consumption decreased in the stress group during stress days compared to their pre-stress state in the 129SVEV mice, but did not change in the C57BL/6J mice (stress session X mouse strain interaction: F(1,114) = 22.34, p < 0.001; Figs 3C/4C). Body weight decreased in response to stress in both strains of mice (main effect of stress session: F(1,111) = 115.64, p < 0.001; Figs 3D/4D).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of 12% ethanol consumption before and during stress in 129SVEV mice. “Pre-stress” values for fluid consumption represent the mean (SEM) of control mice (n = 40) and the mean (SEM) of mice designated to undergo the “stress” procedure (n = 47) collected on days 1 to 3. “No stress” values represent the mean (SEM) of the 40 control mice that did not undergo restraint stress during days 4–7. “Stress” values represent the mean (SEM) of 47 mice that underwent restraint stress on days 4 to 7. (A) Ethanol preference (*p < 0.001 compared to “pre-stress” state). (B) Ethanol consumption (*p < 0.001 compared to “pre-stress” state). (C) Average total daily fluid consumption (*p = 0.005 compared to “pre-stress state). (D) Average body weight before stress procedure and following 4 days of restraint stress (*p < 0.001 compared to “pre-stress” state).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of 12% ethanol preference before and during stress in C58BL/6J mice. “Pre-stress” values for fluid consumption represent the mean (SEM) of control mice (n = 15) and mean (SEM) of mice designated to undergo the “stress” procedure (n = 15) collected on days 1–3. “No stress” values represent the mean (SEM) of the 15 control mice that did not undergo restraint stress during days 4–7. “Stress” values represent the mean (SEM) of 15 mice that underwent restraint stress on days 4–7. (A) Ethanol preference (*p = 0.004 compared to “pre-stress” state). (B) Ethanol consumption. (C) Average total daily fluid consumption. (D) Average body weight before stress procedure and following 4 days of restraint stress (*p = 0.001 compared to “pre-stress” state).

Two-hour limited-access studies showed that stress-induced increase in ethanol preference did not occur within the first two hours following termination of stress. Blood ethanol levels were < 10 mg% in each group (data not shown).

Receptor Blockade

To test the hypothesis that increased ethanol consumption in 129SVEV mice was related to activation of hypothalamic and/or extra-hypothalamic CRF during the stress periods, mice received the CRF-1-receptor antagonist, R121919 [15 mg/kg (n = 5) or 20 mg/kg (n = 10)] or vehicle (n = 15) 30 minutes prior to the beginning of each stress procedure as described in methods. The three groups did not differ on any measure during the pre-stress period (Fig. 5). Stress-induced plasma corticosterone levels significantly decreased with R121919 administration compared to vehicle-treated mice indicating biological activity of the antagonist (Table 1: main effect of treatment group: F(2,26) = 8.70, p = 0.001; post hoc testing of vehicle vs. 20 mg/kg-treated mice: p = 0.002 and vehicle vs. 15 mg/kg-treated mice: p = 0.025).

Fig. 5.

Effects of the corticotropin releasing factor type one receptor antagonist, R121919, or vehicle on 12% ethanol consumption during stress in 129SVEV mice. “Pre-stress” values for fluid consumption, collected on days 1–3 of ethanol exposure, represent the means (SEM) of mice designated to receive 15 mg/kg (n = 5) or 20 mg/kg (n = 10) of R121919 or vehicle (n = 15). “Stress” values represent the means (SEM) of each group of mice during days 4–7 of restraint stress. (A) Ethanol preference (*p = 0.001 compared to pre-stress vehicle; **p = 0.013 compared to pre-stress 15 mg/kg; +p = 0.005 compared to pre-stress 20 mg/kg). (B) Ethanol consumption (*p = 0.004 compared to pre-stress vehicle; **p = 0.05 compared to pre-stress 15 mg/kg; +p = 0.047 compared to pre-stress 20 mg/kg). (C) Average total daily fluid consumption (*p = 0.031 compared to 20 mg/kg. (D) Average body weight (*p < 0.001 compared to pre-stress vehicle; **p.012 compared to pre-stress 15 mg/kg; +p < 0.001 compared to 20 mg/kg).

Table 1.

Plasma Corticosterone Levels (ng/ml) of Antagonist Treatment Groups

| Condition | R121919(15 mg/kg) | Vehicle | R121919(20 mg/kg) | Vehicle | Antalarmin (20 mg/kg) | Vehicle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress | 490 ± 34 (n = 5) 418–580 |

672 ± 80 (n = 5) 433–784 |

318 ± 30 (n = 10) 204–446 |

523 ± 44 (n = 10) 302–529 |

552 ± 47 (n = 14) 348–880 |

674 ± 35 (n = 13) 425–839 |

Plasma corticosterone (ng/ml) levels of three antagonist treatment groups. Values for corticosterone levels represent the mean (SEM), Bold values represent the range of corticosterone levels.

In contrast to the hypothesis, all three groups (vehicle and 2 active drug groups) responded to the stress procedure with a significant increase in ethanol preference (main effect of session: F 1,26) = 35.93, p < 0.001). Moreover, the increase in ethanol preference during stress did not differ among the 3 groups (Fig. 5A). Additionally, all three groups responded to the stress procedure with a significant increase in ethanol consumption (main effect of session: F(1,26) = 21.84, p < 0.001), and the increase in ethanol consumption during stress did not differ among the 3 groups (Fig. 5B). During the stress period, total fluid consumption was greater in the 15 mg/kg group compared to the 20 mg/kg group (p = 0.031; Fig. 5C). All three groups lost weight following stress compared to their pre-stress weights (main effect of session: F(1,26) = 127.21, p < 0.001; Fig. 5D).

To corroborate the lack of efficacy of R121919 in blocking stress-induced changes in ethanol, experiments were conducted with a second CRF-1 receptor antagonist, Antalarmin. The vehicle (n = 16) and Antalarmin, 20 mg/kg group (n = 15) did not differ on any measure during the pre-stress period. Similar to R121919, Antalarmin and vehicle groups responded to the stress procedure with a significant increase in ethanol preference (main effect of session, F(1,31) = 78.78, p < 0.001). Moreover, the increase in ethanol preference during stress did not differ among the groups (Fig. 6). Ethanol consumption significantly increased in response to stress (main effect of session: F(1,31) = 15.60, p < 0.001). Compared to the pre-stress state, body weight decreased in both groups (main effect of session: F(1,31) = 66.75, p < 0.001).

Fig. 6.

Effects of the corticotropin releasing factor type one receptor antagonist, Antalarmin, or vehicle on 12% ethanol consumption during stress in 129SVEV mice. “Pre-stress” values for fluid consumption, collected on days 1–3 of ethanol exposure, represent the means (SEM) of mice designated to receive Antalarmin, 20 mg/kg (n = 15) or vehicle (n = 20). “Stress” values represent the means (SEM) of each group of mice during days 4–7 of restraint stress. (A) Ethanol preference (*p < 0.001 compared to “pre-stress” state). (B) Ethanol consumption (*p < 0.001 compared to “pre-stress” state). (C) Average total daily fluid consumption. (*p = 0.029 compared to vehicle in “stress” state). (D) Average body weight (*p < 0.001 compared to “pre-stress” state).

To test the hypothesis that increased ethanol consumption in 129SVEV mice was related to increased plasma corticosterone levels during the stress periods, mice received two doses of the glucocorticoid receptor antagonist, Mifepristone [25 µg/kg (n = 8); 50 µg/kg (n = 23) or vehicle (n = 32)] prior to the morning stress period as described in methods. The three groups responded to the stress procedure with an increase in ethanol preference (F(1,58) = 21.32, p < 0.001). Moreover, ethanol preference during stress did not differ among the groups (Fig. 7A). Ethanol consumption did not increase in any group during stress (Fig. 7B). Overall total fluid consumption decreased during stress (F(1,63) = 16.37, p < 0.001); however, comparison of individual groups indicated that the 25 µg/kg group did not have a decrease in fluid consumption. Body weight fell significantly in all groups during stress (F(l,34) = 99.35, p < 0.001). Thus, similar to the other two receptor antagonists, Mifepristone did not block the stress-induced change in ethanol preference.

Fig. 7.

Effects of the glucocorticoid receptor antagonist, Mifepristone, or vehicle on 12% ethanol consumption during stress in 129SVEV mice. “Pre-stress” values for fluid consumption, collected on days 1–3 of ethanol exposure, represent the means (SEM) of mice designated to receive 25 µg/kg (n = 8) or 50 µg/kg (n = 23) of Mifepristone or vehicle (n = 32). “Stress” values represent the means (SEM) of each group of mice during days 4–7 of restraint stress. (A) Ethanol preference (*p < 0.001 compared to pre-stress vehicle; **p = 0.001 compared to pre-stress 25 µg/kg; +p < 0.001 compared to pre-stress 50 µg/kg). (B) Ethanol consumption. (C) Average total daily fluid consumption. (D) Average body weight before stress procedure and following 4 days of restraint stress.

The next experiment was performed to test the influence of the three receptor antagonists on nonstressed ethanol drinking. Following drinking stabilization on 12% ethanol 129SVEV mice received R121919 [20 mg/kg; (n = 11)], Antalarmin [20 mg/kg; (n = 11)], Mifepristone [50 µg/kg; (n = 11)] or vehicle (n = 11) during nonstressed conditions as described in methods. The larger dose of each antagonist was employed. Fig. 8 shows that there were no differences in either ethanol preference or ethanol consumption between antagonist and vehicle conditions (R121919, preference: F(1,20) = 0.07, p = 0.802; consumption: F(1,20) = 0.33, p = 0.575; Antalarmin, preference: F(l,20) = 0.51, p = 0.483; consumption: F(1,20) = 0.57, p = 0.456); Mifepristone, preference: F(1,20) = 3.69, p = 0.069; consumption: F(1,20) = 1.54, p = 0.229).

Fig. 8.

Effects of receptor antagonists on nonstressed ethanol preference and consumption 129SVEV mice. Following stabilization on a 12% ethanol solution, mice received R121919 (20 mg/kg; n = 11), Antalarmin (20 mg/kg; n = 11), Mifepristone (50 µg/kg; n = 11) or vehicle each day for 4 days. “Treatment” values represent the means (SEM) of each group of mice during days 4–7 of treatment with the indicated receptor antagonist and its vehicle.

Corticosterone Treatment

To test the hypothesis that glucocorticoids modulate ethanol preference independent of CRF activation, both strains (129SVEV and C57BL/6J) of mice underwent adrenalectomy, recovered for 2 days and then received pellets containing corticosterone. A control group of mice underwent sham adrenalectomy and received placebo pellets. Five days later and prior to ethanol exposure, corticosterone levels were measured. Mice were divided into 2 groups: a high group, in which mice had corticosterone levels greater than 100 ng/ml (n = 16 129SVEV mice and n = 10 C57BL/6J mice) and a low group (n = 15, 129SVEV mice and n = 8, C57BL/6J mice), in which mice had corticosterone levels less than 100 ng/ml. The sham/placebo group (n = 10) was not placed in the analysis since these animals maintain a normal corticosterone circadian rhythm and are not part of a glucocorticoid dose–response. Plasma corticosterone levels at the start and finish of the experiment are listed for the 3 groups in Table 2.

Table 2.

Plasma Corticosterone (ng/ml) Levels Following Implantation of Pellet

| Condition | 129 SVEV Prior to drinking |

129 SVEV End of drinking |

C57BL/6J Prior to drinking |

C57BL/6J End of drinking |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adrenalectomy/low corticosterone |

31 ± 5 (n = 15) | 74 ± 14 | 31 ± 6 (n = 10) | 56 ±24 |

| 8–79 | 3–146 | 7–68 | 5–196 | |

| Adrenalectomy/high corticosterone |

246 ± 52 (n = 14) | 165 ± 32 | 293 ± 43 (n = 10) | 210 ± 54 |

| 85–725 | 17–512 | 119–513 | 51–555 | |

| Sham/placebo | 116 ± 32 (n = 5) | 301 ± 72 | 176 ± 37 (n = 5) | 95 ±24 |

| 47–208 | 86–426 | 93–248 | 34–149 |

Plasma corticosterone (ng/ml) levels following implantation of pellet of three conditions. Values for corticosterone levels represent the mean (SEM). Bold values represent the range of corticosterone levels.

Following 5 days of recovery from surgery, mice were given access to incremental concentrations of ethanol starting with 3% ethanol (v/v) versus water for 2 days, 6% ethanol and water for 2 days and finally 12% ethanol versus water for 3 days. Bottle positions were switched every day to avoid side preference. Ethanol and water consumption were recorded daily. Data are presented as mean (SEM) of the final 3 days during which mice had access to 12% ethanol or water.

As evident in Figs 9 and 10, higher corticosterone levels were associated with lower ethanol preference in both strains of mice (main effect of corticosterone group: F(1,44) = 55.77, p < 0.001). Furthermore, the effect was greater in C57BL/6J mice than in 129SVEV mice (mouse strain X corticosterone group interaction: F(1,44) = 18.99, p < 0.001). That is, there was a greater decrease in ethanol preference associated with high corticosterone in the C57BL/6J mice compared to that in the 129SVEV mice. In addition, total ethanol consumption was lower in mice with high corticosterone than in those with low corticosterone following surgery (main effect of corticosterone group: F(1,44) = 4.33, p = 0.043). Higher corticosterone was also associated with greater total fluid consumption across the entire sample (main effect of corticosterone group: F(1,44) = 10.18,p = 0.003), which reflected an effect of high corticosterone in fluid consumption in the C57BL/6J mice but not in the 129SVEV mice, for whom total fluid consumption did not differ depending on corticosterone level (mouse strain X corticosterone group interaction: F(1,44) = 4.42, p = 0.041). Body weight was less in mice with lower corticosterone than in those with higher corticosterone (main effect of corticosterone group: F(1,44) = 5.31, p = 0.026), both before and after drinking session. Moreover, C57BL/6J mice with higher corticosterone levels following drinking lost more weight than did those in the low-corticosterone group, but this effect was not seen in the 129SVEV mice (session X mouse strain X corticosterone group interaction: F(1,44) = 4.87,p = 0.033).

Fig. 9.

Comparison of ethanol consumption in sham or adrenalectomized 129SVEV mice replaced with pellets containing corticosterone or placebo. Values for fluid consumption represent the mean (SEM) during 3 days access to 12% ethanol solution and water. (A) Ethanol preference (*p = 0.004; high vs. low). (B) Ethanol consumption (*p = 0.035; high vs. low). (C) Total fluid consumption. (D) Body weight before and after 1 week of ethanol exposure.

Fig. 10.

Comparison of ethanol consumption in sham or adrenalectomized C57BL/6J mice replaced with pellets containing corticosterone or placebo. Values for fluid consumption represent the mean (SEM) during 3 days access to 12% ethanol solution and water. (A) Ethanol preference (*p < 0.001; high vs. low). (B) Ethanol consumption (*p = 0.01; high vs. low). (C) Total fluid consumption (*p = 0.014; high vs. low). (D) Body weight (*p = 0.021; high vs. low).

DISCUSSION

Two strains of mice (129SVEV and C57BL/6J) underwent 1 hour of restraint stress twice per day for 4 days. The restraint stress protocol increased ethanol preference and consumption in 129SVEV mice but not in C57BL/6J mice. Part of the rationale for choosing an ethanol-preferring strain of mice was that they may show a rate-dependent effect on ethanol consumption. The rationale for choosing non-ethanol preferring mice was the possibility that stress may play a more significant role in increasing drinking in normal subjects (i.e., those that are not genetically predisposed or nonpreferring). In line with our hypothesis, we found that restraint stress modestly increased ethanol preference and consumption in the ethanol nonpreferring 129SVEV mice but not in the ethanol preferring C57BL/6J mice. Although, 129SVEV mice showed a greater corticosterone response to restraint stress compared to C57BL/6J mice, it is not clear if this difference in glucocorticoid response was related to differences in stress-induced drinking between the strains.

In the next series of experiments, we sought to understand the mechanism(s) responsible for increased ethanol consumption during restraint stress in the 129SVEV mice. Since CRF secretion is part of the response to stress then it follows that CRF may be important in ethanol drinking. To this end, we attempted to block stress-induced change in ethanol consumption with two CRF receptor-1 antagonists, R121919 and Antalarmin. Although the antagonists reduced corticosterone levels compared to vehicle, indicating biological activity, neither agent was able to decrease stress-induced change in ethanol consumption in this model. This was a surprising finding since the restraint stress procedure markedly activates the HPA axis. Moreover, neither antagonist influenced non-stressed ethanol drinking This is consistent with what Koob and co-workers found when administrating the CRF receptor antagonist D-Phe-CRF(12 to 41) to nonstressed rats (Valdez et al., 2002).

The failure of the CRF receptor-1 antagonists to block basal or restraint stress-induced increase in drinking was probably not related to an inadequate dose. In vitro studies have found that R121919 is highly selective for the CRF-1 receptor demonstrating nearly 50% receptor occupancy at 2.5 mg/kg and 100% occupancy at 20 mg/kg (Heinrichs et al., 2002). Antalarmin has a Ki value of 1.0 nm and antagonizes central and peripheral actions of CRF in vivo at a dose of 20 mg/kg (Webster et al., 1996). Antalarmin, at doses of 10 or 20 mg/kg, has also been shown to inhibit fear conditioning (Deak et al., 1999), inhibit CRF- and novelty-induced anxiety-like behaviors (Zorrilla et al., 2002) and inhibit the locomotor activating effects of CRF (Zorrilla et al., 2002). Moreover, the CRF-1 receptor antagonist d-Phe-CRF(12 to 41) has been shown to decrease ethanol drinking in C57BL/6J mice during withdrawal from intermittent ethanol exposure (Finn et al., 2007). This has also been shown in other rodents following ethanol withdrawal/deprivation, following dependence-induced drinking (Funk et al., 2004, 2007; Roberts et al., 2000, 2001) as well as in Marchigian-Sardinian preferring rats using an operant self-administration model (Hansson et al., 2006).

Although pharmacological manipulation of CRF reduces ethanol consumption following ethanol withdrawal and/or deprivation, another picture emerges from studies of both over-expression and the targeted disruption of the CRF- or the CRF receptor-1 gene in the absence of ethanol deprivation. For example, Spanagel and co-workers reported that in mice lacking a functional CRF-1 receptor, stress led to enhanced ethanol intake (Sillaber et al., 2002). Hodge and coworkers showed that CRF-deficient mice consume twice as much ethanol as wild type mice both in continuous and limited-access paradigms (Olive et al., 2003). Further, Phillips and co-workers demonstrated that over-expression of CRF decreases ethanol drinking in a transgenic mouse model (Palmer et al., 2004). Therefore, the role of CRF in modulating ethanol consumption appears to be complex and varies depending on previous ethanol exposure, whether withdrawal and or ethanol deprivation were present and depending on the presence or absence of stress.

Glucocorticoids can sensitize mesolimbic dopaminergic neurotransmission and thus modulate reinforcement and reward to psychostimulants independent of CRF action (Piazza et al., 1996). Therefore in the next series of experiments, we tested the importance of corticosterone in modulating stress-induced change in ethanol consumption. This was done in two ways: utilizing a glucocorticoid receptor antagonist and then by administering corticosterone to the mice. The 129 SVEV mice were administered three doses of a glucocorticoid receptor antagonist, Mifepristone, or vehicle during the restraint stress procedure. The highest dose caused illness or death. Neither of the lower doses of Mifepristone blocked restraint stress-induced increase in ethanol preference. Moreover, the receptor antagonist did not influence nonstressed drinking either.

In the last series of experiments, 129SVEV and C57BL/6J mice underwent active or sham adrenalectomy and then pellets containing various concentrations of corticosterone or placebo were implanted subcutaneously. Preference and consumption for ethanol versus water was tested. Opposite to the hypothesized direction, high corticosterone levels in the 129 SVEV mice reduced ethanol preference and consumption without altering total fluid intake compared to 129SVEV mice with lower corticosterone levels. In contrast, C57BL/6J mice with high corticosterone levels had a reduction in ethanol preference that was driven by increased water intake suggesting a thirst mechanism being invoked, possibly involving argi-nine vasopressin. Interestingly, the alteration in ethanol and water consumption induced by glucocorticoid administration in the two mouse strains was modulated differentially and influenced by genetic background.

Failure to observe increased ethanol intake in the two-hour limited access experiment calls into question causality between the stressor and the increased ethanol consumption per 24 hours. Indeed, the other experiments in this study indicate that HPA axis hormones and extra-hypothalamic CRF are not involved. The data suggests that there is a delay between what is activated by the stress procedure and how that influences ethanol consumption hours later. At this juncture, we do not know the mechanisms responsible for stress-induced change in ethanol consumption in the model. Possibilities include group II metabotropic glutamate receptors (Zhao et al., 2006), catecholamines, GABAergic systems, (Koob, 2003), and/or NPY (Pandey et al., 2005). Regardless, several important points emerge: First, this will be a useful addition to the existing models for investigating how stress may trigger modest increases in ethanol consumption in social drinkers, thereby reinforcing self-medicating behaviors to cope with stress. Second, the observation that stress enhanced ethanol consumption in one strain of mice but not in another strain adds to the growing body of literature informing us of the importance of genetic determinants in providing susceptibility for this effect (Vengeliene et al., 2003). Third, it is intriguing that the stress responsive strain is ethanol nonpreferring whereas the nonresponsive strain is ethanol preferring. This suggests a ceiling effect may deny us the ability to observe the phenomenon in ethanol preferring strains. Fourth, glucocorticoid administration resulting in high serum corticosterone levels actually reduced ethanol preference and consumption in both mouse strains but in a strain-specific manner.

There are several weaknesses to the study. We were not able to implicate the neural circuitry mediating the effect of stress on ethanol consumption. However, future studies will explore a series of candidate systems outline above. Second, the implantation of corticosterone pellets does not mimic the circadian pattern of hormone release nor the stress pattern of hormone release. Third, it is unclear how the pre-treatment ethanol exposure period and blood sampling influenced the subsequent responses to the stress procedure. Fourth, Becker and Lopez (2004) have aptly stated that what is needed in this field is an animal model that allows stress–ethanol interactions to be studied during acquisition that additionally mimics aspects of human alcoholism including (1) high levels of voluntary ethanol consumption and (2) the existence of individual differences in ethanol self-administration that are genetically linked (Breese et al., 2005). Although this model fulfills the genetic criteria, it is too early to say whether the paradigm can be modified to induce higher levels of ethanol consumption. However, our intention was not to produce a stress model that resulted in high levels of ethanol consumption that mimicked consumption in an alcohol-dependent person. Rather our goal was to determine if a stress model could invoke a mild to moderate increase in ethanol preference and consumption mimicking individuals who escalate their ethanol consumption to reduce anxiety during stressful situations. Further studies are needed to determine if this aim was achieved.

In summary, these data show the restraint model for stress can increase ethanol preference and consumption in 129 SVEV (ethanol nonpreferring) but not in C57BL/6J (ethanol preferring) mice. Glucocorticoid receptor and CRF-1 receptor blockade did not blunt basal or stress-induced increase in ethanol consumption nor did administration of corticosterone mimic the effects of restraint stress on ethanol consumption. These findings suggest the mechanism responsible for increasing ethanol consumption in this model is independent of the HPA axis and extra-hypothalamic CRF.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grants AA09000 (GSW)and AA12303 (GSW)and the NIH Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

REFERENCES

- Becker HC, Lopez MF. Increased ethanol drinking after repeated chronic ethanol exposure and withdrawal experience in C57BL/6 mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:1829–1838. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000149977.95306.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breese GR, Chu K, Dayas CV, Funk D, Knapp DJ, Koob GF, Le DA, O’Dell LE, Overstreet DH, Roberts AJ, Sinha R, Valdez GR, Weiss F. Stress enhancement of craving during sobriety: a risk for relapse. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:185–195. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000153544.83656.3c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breese GR, Knapp DJ, Overstreet DH. Stress-induced anxiety-like behavior during abstinence from previous chronic ethanol exposure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:191A. [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Wilcoxen KM, Huang CQ, Xie YF, McCarthy JR, Webb TR, Zhu YF, Saunders J, Liu XJ, Chen TK, Bozigian H, Grigoriadis DE. Design of 2,5-dimethyl-3-(6-dimethyl-4-methylpyridin-3-yl)-7-dipropylamin-opyrazolo[l,5-a]pyrimidine (NBI 30775/R121919) and structure-activity relationships of a series of potent and orally active corticotropin-releasing factor receptor antagonists. J Med Chem. 2004;47:4787–4798. doi: 10.1021/jm040058e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chester JA, Blose AM, Zweifel M, Froehlich JC. Effects of stress on alcohol consumption in rats selectively bred for high or low alcohol drinking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:385–393. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000117830.54371.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deak T, Nguyen KT, Ehrlich AL, Watkins LR, Spencer RL, Maier SF, Licinio J, Wong ML, Chrousos GP, Webster E, Gold PW. The impact of the nonpeptide corticotropin-releasing hormone antagonist anta-larmin on behavioral and endocrine responses to stress. Endocrinology. 1999;140:79–86. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.1.6415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federenko IS, Nagamine M, Hellhammer DH, Wadhwa PD, Wust S. The heritability of hypothalamus pituitary adrenal axis responses to psychosocial stress is context dependent. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:6244–6250. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn DA, Snelling C, Fretwell AM, Tanchuck MA, Underwood L, Cole M, Crabbe JC, Roberts AJ. Increased drinking during withdrawal from intermittent ethanol exposure is blocked by the CRF receptor antagonist D-Phe-CRF(12–41) Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:939–949. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk D, Vohra S, Le AD. Influence of stressors on the rewarding effects of alcohol in Wistar rats: studies with alcohol deprivation and place conditioning. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;176:82–87. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1859-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk CK, Zorrilla EP, Lee MJ, Rice KC, Koob GF. Corticotropin-releasing factor 1 antagonists selectively reduce ethanol self-administration in ethanol-dependent rats. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson AC, Cippitelli A, Sommer WH, Fedeli A, Bjork K, Soverchia L, Terasmaa A, Massi M, Heilig M, Ciccocioppo R. Variation at the rat Crhrl locus and sensitivity to relapse into alcohol seeking induced by environmental stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:15236–15241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604419103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs SC, De Souza EB, Schulteis G, Lapsansky JL, Grigoriadis DE. Brain penetrance, receptor occupancy and antistress in vivo efficacy of a small molecule corticotropin releasing factor type I receptor selective antagonist. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27:194–202. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00299-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsgodt KH, Lukas SE, Elman I. Psychosocial stress and the duration of cocaine use in non-treatment seeking individuals with cocaine dependence. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2003;29:539–551. doi: 10.1081/ada-120023457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF. Alcoholism: allostasis and beyond. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:232–243. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000057122.36127.C2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lé A, Shaham Y. Neurobiology of relapse to alcohol in rats. Pharmacol Ther. 2002;94:137–156. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(02)00200-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu SJ, Cull-Candy SG. Activity-dependent change in AMPA receptor properties in cerebellar stellate cells. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3881–3889. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-10-03881.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao J, Regelson W, Kalimi M. Molecular mechanism of RU 486 action: a review. Mol Cell Biochem. 1992;109:1–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00230867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noone M, Dua J, Markham R. Stress, cognitive factors, and coping resources as predictors of relapse in alcoholics. Addict Behav. 1999;24:687–693. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Dell LE, Roberts AJ, Smith RT, Koob GF. Enhanced alcohol self-administration after intermittent versus continuous alcohol vapor exposure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:1676–1682. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000145781.11923.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olive MF, Mehmert KK, Koenig HN, Camarini R, Kim JA, Nannini MA, Ou CJ, Hodge CW. A role for corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) in ethanol consumption, sensitivity, and reward as revealed by CRF-deficient mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;165:181–187. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1248-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer AA, Sharpe AL, Burkhart-Kasch S, McKinnon CS, Coste SC, Stenzel-Poore MP, Phillips TJ. Corticotropin-releasing factor overex-pression decreases ethanol drinking and increases sensitivity to the sedative effects of ethanol. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;176:386–397. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1896-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey SC, Zhang H, Roy A, Xu T. Deficits in amygdaloid cAMP-responsive element-binding protein signaling play a role in genetic predisposition to anxiety and alcoholism. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2762–2773. doi: 10.1172/JCI24381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza PV, Rouge-Pont F, Deroche V, Maccari S, Simon H, Le Moal M. Glucocorticoids have state-dependent stimulant effects on the mesencephalic dopaminergic transmission. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8716–8720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AJ, Cole M, Koob GF. Intra-amygdala muscimol decreases operant ethanol self-administration in dependent rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:1289–1298. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AJ, Gold LH, Polis I, McDonald JS, Filliol D, Kieffer BL, Koob GF. Increased ethanol self-administration in delta-opioid receptor knockout mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1249–1256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AJ, Heyser CJ, Cole M, Griffin P, Koob GF. Excessive ethanol drinking following a history of dependence: animal model of allostasis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;22:581–594. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00167-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson HH. Initiation of ethanol reinforcement using a sucrose-substitution procedure in food- and water-sated rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1986;10:436–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1986.tb05120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson HH, Tolliver GA, Lumeng L, Li TK. Ethanol reinforcement in the alcohol nonpreferring rat: initiation using behavioral techniques without food restriction. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1989;13:378–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1989.tb00339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sillaber I, Rammes G, Zimmermann S, Mahal B, Zieglgansberger W, Wurst W, Holsboer F, Spanagel R. Enhanced and delayed stress-induced alcohol drinking in mice lacking functional CRH1 receptors. Science. 2002;296:931–933. doi: 10.1126/science.1069836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R. How does stress increase risk of drug abuse and relapse? Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;158:343–359. doi: 10.1007/s002130100917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R, Talih M, Malison R, Cooney N, Anderson GM, Kreek MJ. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and sympatho-adreno-medullary responses during stress-induced and drug cue-induced cocaine craving states. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;170:62–72. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1525-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman S, Dent CW. One-year prospective prediction of drug use from stress-related variables. Subst Use Misuse. 2000;35:717–735. doi: 10.3109/10826080009148418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez GR, Roberts AJ, Chan K, Davis H, Brennan M, Zorrilla EP, Koob GF. Increased ethanol self-administration and anxiety-like behavior during acute ethanol withdrawal and protracted abstinence: regulation by corticotropin-releasing factor. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:1494–1501. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000033120.51856.F0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vengeliene V, Siegmund S, Singer MV, Sinclair JD, Li TK, Spanagel R. A comparative study on alcohol-preferring rat lines: effects of deprivation and stress phases on voluntary alcohol intake. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1048–1054. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000075829.81211.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster EL, Lewis DB, Torpy DJ, Zachman EK, Rice KC, Chrousos GP. In vivo and in vitro characterization of antalarmin, a nonpeptide corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) receptor antagonist: suppression of pituitary ACTH release and peripheral inflammation. Endocrinology. 1996;137:5747–5750. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.12.8940412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Dayas CV, Aujla H, Baptista MA, Martin-Fardon R, Weiss F. Activation of group II metabotropic glutamate receptors attenuates both stress and cue-induced ethanol-seeking and modulates c-fos expression in the hippocampus and amygdala. J Neurosci. 2006;26:9967–9974. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2384-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorrilla EP, Koob GF. The therapeutic potential of CRF1 antagonists for anxiety. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2004;13:799–828. doi: 10.1517/13543784.13.7.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorrilla EP, Valdez GR, Nozulak J, Koob GF, Markou A. Effects of antalarmin, a CRF type 1 receptor antagonist, on anxiety-like behavior and motor activation in the rat. Brain Res. 2002;952:188–199. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03189-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]