Consider the last time you answered a questionnaire. Did it contain questions that were vague or hard to understand? If yes, did you answer these questions anyway, unsure if your interpretation aligned with what the survey developer was thinking? By the time you finished the survey, you were probably annoyed by the unclear nature of the task you had just completed. If any of this sounds familiar, you are not alone, as these types of communication failures are commonplace in questionnaires.1–3 And if you consider how often questionnaires are used in medical education for evaluation and educational research, it is clear that the problems described above have important implications for the field. Fortunately, confusing survey questions can be avoided when survey developers use established survey design procedures.

In 2 recent Journal of Graduate Medical Education editorials,4,5 the authors encouraged graduate medical education (GME) educators and researchers to use more systematic and rigorous survey design processes. Specifically, the authors proposed a 6-step decision process for questionnaire designers to use. In this article, we expand on that effort by considering the fifth of the 6 decision steps, specifically, the following question: “Will my respondents interpret my items in the manner that I intended?” To address this question, we describe in detail a critical, yet largely unfamiliar, step in the survey design process: cognitive interviewing.

Questionnaires are regularly used to investigate topics in medical education research, and it may seem a straightforward process to script standardized survey questions. However, a large body of evidence demonstrates that items the researchers thought to be perfectly clear are often subject to significant misinterpretation, or otherwise fail to measure what was intended.1,2 For instance, abstract terms like “health professional” tend to conjure up a wide range of interpretations that may depart markedly from those the questionnaire designer had in mind. In this example, survey respondents may choose to include or exclude marriage counselors, yoga instructors, dental hygienists, medical office receptionists, and so on, in their own conceptions of “health professional.” At the same time, terms that are precise but technical in nature can produce unintended interpretations; for example, a survey question about “receiving a dental sealant” could be misinterpreted by a survey respondent as “getting a filling.”2

The method we describe here, termed “cognitive interviewing” or “cognitive testing,” is an evidence-based, qualitative method specifically designed to investigate whether a survey question—whether attitudinal, behavioral, or factual in nature—fulfills its intended purpose (B O X). The method relies on interviews with individuals who are specifically recruited. These individuals are presented with survey questions in much the same way as survey respondents will be administered the final draft of the questionnaire. Cognitive interviews are conducted before data collection (pretesting), during data collection, or even after the survey has been administered, as a quality assurance procedure.

During the 1980s, cognitive interviewing grew out of the field of experimental psychology; common definitions of cognitive interviewing reflect those origins and emphasis. For example, Willis6 states, “Cognitive interviewing is a psychologically oriented method for empirically studying the way in which individuals mentally process and respond to survey questionnaires.” For its theoretical underpinning, cognitive interviewing has traditionally relied upon the 4-stage cognitive model introduced by Tourangeau.7 This model describes the survey response process as involving (1) comprehension, (2) retrieval of information, (3) judgment or estimation, and (4) selection of a response to the question. For example, mental processing of the question “In the past year, how many times have you participated in a formal educational program?” presumably requires a respondent to comprehend and interpret critical terms and phrases (eg, “in the past year” and “formal educational program”); to recall the correct answer; to decide to report an accurate number (rather than, for example, providing a higher value); and then to produce an answer that matches the survey requirements (eg, reporting “5 times” rather than “frequently”). Most often, comprehension problems dominate. For example, it may be found that the term “formal educational program” is variably interpreted. In other words, respondents may be unsure which activities to count and, furthermore, may not know what type of participation is being asked about (eg, participation as a student, teacher, or administrator).

More recently, cognitive interviewing has to some extent been reconceptualized as a sociological/anthropological endeavor, in that it emphasizes not only the individualistic mental processing of survey items but also the background social context that may influence how well questions meaningfully capture the life of the respondent.8 Especially as surveys increasingly reflect a range of environments and cultures that may differ widely, this viewpoint has become increasingly popular. From this perspective, it is worth considering that the nature of medical education may vary across countries and medical systems, such that the definition of a term as seemingly simple as “graduate medical education” might itself lack uniformity.

Process Overview

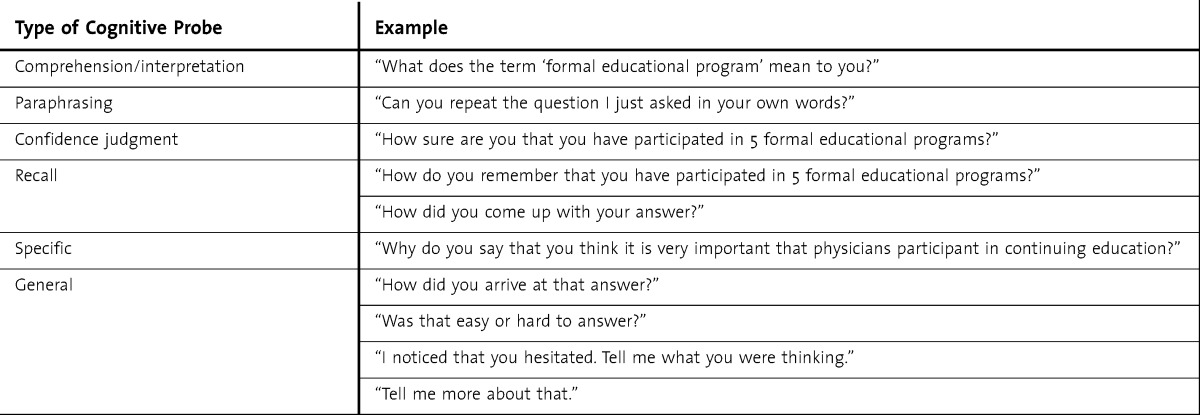

Cognitive interviewing is conducted using 2 key procedures that characterize the method and that require more than the usual practice of a respondent simply answering a presented survey question. First, think-aloud interviewing requests that the survey respondents (often renamed subjects or participants) actively verbalize their thoughts as they attempt to answer the survey questions.9 Here the role of the interviewer is mainly to support this activity by asking the subject to “keep talking” and to record the resultant verbal record, or so-called cognitive protocol, for later analysis. For this procedure to be effective, it is necessary that the subject's think-aloud stream contain diagnostic information relevant to the assessment of survey question function, as opposed to tangential or meandering free association. The alternative procedure, which has gained considerable traction over the past 20 years, is verbal probing, which is a more active form of data collection in which the cognitive interviewer administers a series of probe questions specifically designed to elicit detailed information beyond that normally provided by respondents. Commonly used probes are provided in table 1.

TABLE 1.

Categories and Examples of Cognitive Probe Questions (Adapted from Willis2)

Probes may be systematically fashioned before the interview, in order to search for potential problems (proactive probes), or they may be developed in a nonstandardized way during the interview, often in response to subject behavior (reactive probes). As such, probing is usually a flexible procedure that relies to a significant degree on interviewer adaptability rather than on strict standardization of materials.

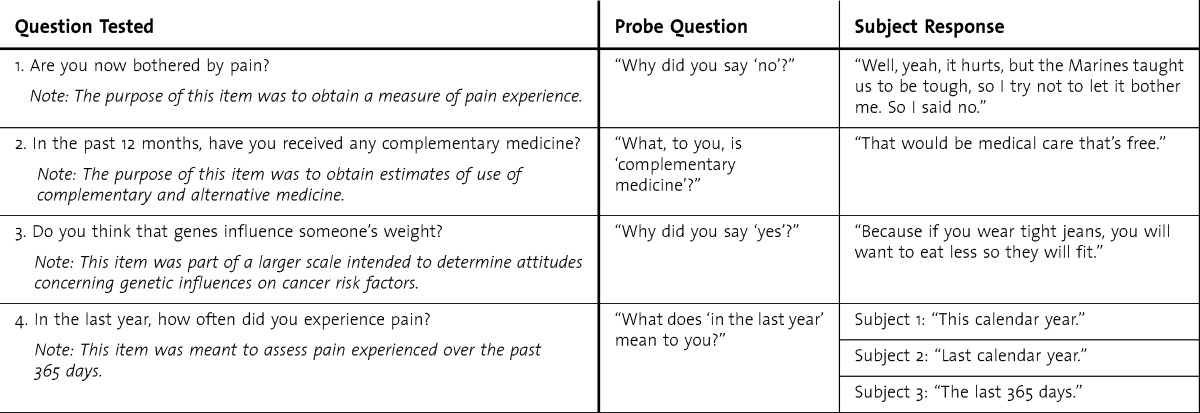

The advantages to a think-aloud procedure is that it presents little in the way of training demands on the interviewer and avoids being too directive in ways that could bias responses. That being said, thinking aloud places a significant burden on subjects, many of whom find the process to be unnatural and difficult. Further, analysis of think-aloud transcripts can be a daunting task because of the sheer quantity of the sometimes meandering verbalizations obtained. Verbal probing, on the other hand, requires more training and thought on the part of the interviewer and, if not done carefully, can create reactivity effects. That is, verbal probing may create bias in the subject's behavior through the additional cognitive demands related to answering probe questions and explaining those answers. For example, probing may lead to more carefully thought-out answers than a survey respondent might typically provide. However, verbal probes are generally efficient, can be targeted toward specific cognitive processes (eg, comprehension of a term or phrase), are well-accepted by subjects, and provide data that are easier to separate into segments and code than think-aloud streams. In practice, think-aloud interviewing and verbal probing are very often used in unison, with a distinct emphasis on the latter. table 2 provides several examples of survey items that were tested with verbal probes during cognitive interviews, revealing varying interpretations.

TABLE 2.

Questionnaire Items Tested via Cognitive Interviewing and Found to Be Confusing or Misinterpreted (Adapted from Willis2)

Analysis of Cognitive Interviews

Because cognitive interviewing is a qualitative procedure, analysis does not rely on strict statistical analysis of numeric data but rather on coding and interpretation of written notes that are taken during the interview (often by the interviewer) or after it (by either the interviewer or an analyst). Such notes often describe substantive observations relevant to item functioning (eg, “Subject was unsure of what we mean by ‘formal educational program,’ in terms of what counts and what should be excluded”). A set of interviews are typically analyzed by combining the notes pertaining to each evaluated item, aggregating across interviews, seeking common themes, and identifying key findings that may indicate departures from the interpretation desired by survey developers. For example, if one finds that there is little concurrence across a range of subjects about what is meant by “formal educational program,” a potential solution may be to explicitly define this term in the survey. Furthermore, if clear patterns are observed where the interpretation of an item is found to be culturally specific, or varies across country or context, the researcher may find it necessary to revisit whether the question can in fact be asked in the same form across these contexts.

Practical Considerations

Cognitive interviewing projects are normally small in scope and may involve just 10 to 30 total subjects. For small-scale GME projects, as few as 5 or 6 subjects may provide useful information to improve survey items, as long as the survey developers are sensitive to the potential for bias in very small samples. Cognitive interviewing is often conducted as an iterative procedure, in which a small round of interviews is conducted (eg, 10); the survey developers analyze and assess their results, make alterations to survey items where necessary, and then conduct an additional round of testing using the modified items. In the previous example, 3 rounds of 10 interviews would likely provide ample opportunity for problematic items to emerge. Such items could then be reevaluated by the survey developer and modified if needed.

Cognitive interviewing is commonly applied to both interviewer-administered and self-administered surveys and for surveys designed for paper- and computer-based administration. Under interviewer administration, it is common to rely on concurrent probing, which consists of probing after each evaluated question is read aloud and answered. The back and forth process of presenting a question, having the subject answer it, and then asking targeted probes appears to function well for interviewer-administered surveys and poses little difficulty for most people. Under self-administration, where the interviewer is normally silent or absent and the respondent completes the survey unaided, the process of retrospective probing is often applied. In retrospective probing, interviewer questions are reserved for a debriefing session that occurs after the subject has completed the questionnaire. Concurrent or retrospective probing can be applied to either interviewer or self-administered surveys, and there are advantages as well as limitations to each. Concurrent probing allows the subject to respond to probes when their thoughts are recent and presumably fresh, whereas retrospective probing requires revisiting thoughts that are more remote in time. However, concurrent probing can disrupt the interview through its imposition of probes in a way that retrospective probing does not.

With proper training, cognitive interviews can be carried out by anyone planning to administer a questionnaire. Because the equipment and logistical requirements are modest—all that is really needed is a quiet place and an audio recorder—it is possible for a wide range of educators or researchers to conduct the activity with subjects who are similar to the target survey population. Usually the objective of recruitment is not to achieve any type of statistical representation but rather to cover the territory by including as wide a range of subjects as possible, given the constraints of time and cost. It is important to note, however, that data obtained from cognitive interviews are qualitative in nature and used to assess and improve survey items, usually before the survey is implemented. As such, these data and the respondents used for the cognitive interviews should not be used as part of the final survey study.

Concluding Thoughts

Creating a survey with evidence of reliability and validity can be difficult. The cognitive interviewing processes outlined here are designed to help GME educators and researchers improve the quality of their surveys and enhance the validity of the conclusions they draw from survey data. Cognitive interviewing is an evidence-based tool that can help survey developers collect validity evidence based on survey content and the thought processes that participants engage in while answering survey questions.2,8–10 As with all of the steps in survey design, the results of cognitive interviewing should be reported in the methods section of research papers. Doing so gives readers greater confidence in the quality of the survey information reported by GME researchers.

Box Glossary

Cognitive interviewing (or cognitive testing)—an evidence-based qualitative method specifically designed to investigate whether a survey question satisfies its intended purpose.

Concurrent probing—a verbal probing technique wherein the interviewer administers the probe question immediately after the respondent has read aloud and answered each survey item.

Proactive verbal probes—a verbal probe that is systematically fashioned before the cognitive interview in order to search for potential problems.

Reactive verbal probes—a verbal probe that is developed in a nonstandardized way during the cognitive interview, often in response to a respondent's behavior.

Reactivity effects—bias in a respondent's behavior caused by the additional cognitive demands related to answering probe questions and explaining those answers (most likely by leading to more carefully thought-out answers than a survey respondent might typically provide).

Verbal probing—a cognitive interviewing technique wherein the interviewer administers a series of probe questions specifically designed to elicit detailed information beyond that normally provided by respondents.

Retrospective probing—a verbal probing technique wherein the interviewer administers the probe questions after the respondent has completed the entire survey (or a portion of the survey).

Think-aloud interviewing—a cognitive interviewing technique wherein survey respondents are asked to actively verbalize their thoughts as they attempt to answer the evaluated survey items.

Footnotes

Gordon B. Willis, PhD, is Cognitive Psychologist, Applied Research Program, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health; and Anthony R. Artino Jr, PhD, is Associate Professor of Medicine and Preventive Medicine & Biometrics, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences.

The authors are US government employees. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the US Department of Defense, the National Institutes of Health, or the US government.

References

- 1.Tourangeau R, Rips LJ, Rasinski K. The Psychology of Survey Response. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Willis GB. Cognitive Interviewing: A Tool for Improving Questionnaire Design. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Willis GB. Cognitive Interviewing: A “How-To” Guide. 1999. http://appliedresearch.cancer.gov/areas/cognitive/interview.pdf. Accessed May 22, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Magee C, Byars L, Rickards G, Artino AR., Jr Tracing the steps of survey design: a graduate medical education research example. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(1):1–5. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00364.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rickards G, Magee C, Artino AR., Jr You can't fix by analysis what you've spoiled by design: developing survey instruments and collecting validity evidence. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(4):407–410. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00239.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willis G. Cognitive aspects of survey methodology. In: Lavrakas P, editor. Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods. Vol 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2009. pp. 103–106. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tourangeau R. Cognitive science and survey methods: a cognitive perspective. In: Jabine T, Straf M, Tanur J, Tourangeau R, editors. Cognitive Aspects of Survey Design: Building a Bridge between Disciplines. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1984. pp. 73–100. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerber ER. The view from anthropology: ethnography and the cognitive interview. In: Sirken M, Herrmann D, Schechter S, Schwarz N, Tanur J, Tourangeau R, editors. Cognition and Survey Research. New York, NY: Wiley; 1999. pp. 217–234. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ericsson KA, Simon HA. Verbal reports as data. Psychol Rev. 1980;87:215–251. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conrad F, Blair J. Data quality in cognitive interviews: the case for verbal reports. In: Presser S, Rothgeb J, Couper M, Lessler J, Martin E, Martin J, Singer E, editors. Questionnaire Development Evaluation and Testing Methods. Vol. 2004. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons; pp. 67–87. [Google Scholar]