Abstract

Background

A large volume of literature has documented racial disparities in the delivery of cardiovascular care in the United States and that decreased access to procedures and undertreatment lead to worse outcomes. A lack of diversity among physicians is considered to be a major contributor. The fellowship training program in cardiovascular medicine at The Ohio State University Medical Center had never trained a fellow from a minority group underrepresented in medicine (URM) before 2007.

Intervention

In 2005, the fellowship made it a priority to recruit and match URM candidates in an effort to address the community's lack of diversity and disparities in cardiovascular care.

Methods

Program leaders revised the recruitment process, making diversity a high priority. Faculty met with members of diverse residency programs during visits to other institutions, the focus of interview day was changed to highlight mentorship, additional targeted postinterview communications reached out to highly competitive applicants, and a regular mentoring program was constructed to allow meaningful interaction with URM faculty and fellows.

Results

Since these changes were implemented, the program has successfully matched a URM fellow for 5 consecutive years. Such candidates currently make up 4 of 16 total trainees (25%) in the fellowship in cardiovascular medicine.

Conclusions

The cardiovascular medicine fellowship training program at The Ohio State University was able to revise recruitment to attract competitive URM applicants as part of a concerted effort. Other educational programs facing similar challenges may be able to learn from the university's experiences.

What was known

Research has shown that racial disparities exist in cardiovascular care, and members of minorities underrepresented in medicine (URMs) experience decreased access to procedures and undertreatment.

What is new

A cardiovascular disease fellowship made it a priority to recruit and match URM candidates to address a lack of diversity in the program and disparities in care in the community.

Limitations

Single institution study, small sample, and inability to attribute enhanced recruitment to the intervention (versus the decision to rank URM candidates) limit generalizability.

Bottom line

The intervention resulted in successfully matching URM fellows for 5 consecutive years and may be suitable for adoption or adaptation by other programs.

Introduction

A large volume of literature has documented racial disparities in cardiovascular care in the United States.1 Compared with Non-Hispanic Whites, minorities—primarily African Americans/blacks and Hispanics—suffer from decreased access to cardiac catheterization, percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery bypass graft surgery, and implantation of cardioverter-defibrillators. In addition, undertreatment of hypertension, acute coronary syndromes, and dyslipidemia greatly increases morbidity and mortality in minority populations.2

Data from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) describing minority groups underrepresented in medicine (URMs) within US medical graduates from 1978 to 2008 indicate that only 3.5% of 11 097 practicing cardiologists are African American, 4.5% are Hispanic or Latino (ie, have their origin in the countries of Latin America and the Iberian peninsula consisting of Spain and Portugal), and 0.9% are American Indian/Alaskan.3 Survey data from the 2009–2010 academic year show a total of 178 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education–accredited fellowships in cardiovascular disease. Of 2429 fellows, 105 (4.3%) were African American, 152 (6.3%) were of Hispanic/Latino origin, 2 (0.08%) were American Indian/Alaskan natives, and 2 (0.08%) were Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders.4 This shared gap among the practicing cardiology workforce and trainees in cardiovascular disease is particularly concerning as evidence exists that minority physicians are more likely to care for sicker minority patients, and that minority patients, when offered a choice, are more likely to choose a physician of their own race.5,6

Although some cardiology fellowship programs lack diversity, several programs have a history of training URM cardiologists. Many are historically prestigious medical centers; thus, positions in their residency and fellowship training programs are quite competitive, leading to high rankings during the Medical Specialties Match Program (MSMP)7 for non-URM and URM applicants. In addition to these institutions, medical schools affiliated with historically black colleges and universities produce graduates that are 70% to 85% URMs and have a nearly identical makeup of their graduate medical education programs.8

Before 2007, The Ohio State University (OSU) cardiovascular medicine fellowship training program had never trained a URM cardiologist during its 40-year existence. The objective of this article is to outline the approach initiated by the Division of Cardiovascular Medicine Fellowship Training Program to recruit and match more URM trainees, as it might be useful to other residency or fellowship programs facing similar concerns.

Methods

Setting

A structured cardiology training program has existed at OSU since 1967. Overall, 242 fellows have completed training, and 54 (23%) have assumed academic positions. As of 2011, there were 57 division faculty members, including 3 URMs and 9 women. As cardiology training is 1 of the most competitive specialties in internal medicine, it is routine for the program to receive between 400 and 500 applications per year through the AAMC's Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS).9 Each of these applications contains a curriculum vitae, personal statement, letters of recommendation, and United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) board scores. These are aggregated into an applicant score by the fellowship committee (each section is ranked 1 through 5, with additional rankings for “miscellaneous” and consolidated evaluations for those who are eventually selected to interview); USMLE scores are considered the most objective variable for comparison.

Participants

Fellowship leadership consists of a program director, an associate program director, 10 faculty members who make up the fellowship committee (including the 2 directors and 2 chief fellows), and a nonphysician program coordinator. In addition, the chief of the division of cardiovascular medicine serves as a resource and advocate for the directors and committee within the department of medicine and the medical center.

Intervention

Several contributing factors limiting fellowship diversity were identified. First, the number of URM residents within the internal medicine training program—who make up 25% to 60% of matriculating fellows—had been historically low. Second, the overall number of URM candidates of OSU's fellowship program represented a small fraction of those applying, and their applications tended to be less competitive than those of their non-URM peers. Third, the cardiology faculty lacked URM members. Finally, recruitment and training of URM fellows had never been labeled a priority by program and division leadership. To expand the pool of competitive URM applicants, we focused on revising the approach with the following steps:

Make a Diverse Fellowship Program a Priority

To this end, OSU formed a smaller subcommittee focused on URM recruitment; the subcommittee consisted of a URM fellowship committee member, the program director, and the associate program director. The 2005 recruitment of the senior author (Q.C.), a URM faculty member with interests in training URM fellows, led to his appointment to the fellowship committee. This served as a catalyst in organizing the division's efforts. The subcommittee met to specifically review and rank all URM applicants as a subgroup in parallel to the overall process. Although these candidates were judged by the same universal criteria as all non-URM applicants, the separate screening allowed for a more focused review before they were merged with the larger pool.

Reach Out to Diverse Residency Programs

As part of this step, the fellowship committee planned to meet non-OSU URM residents and inform them about opportunities for cardiology training at OSU. The university already has an annual structured fellowship career day that allows the fellowship committee to identify and interact with all interns and junior residents who have an interest in cardiology. As travel to other traditionally diverse programs would present a strong likelihood of interacting with URM residents with an interest in cardiology, fellowship committee members leveraged already scheduled invitations by the senior author to deliver grand rounds at Emory University, Meharry Medical College, Morehouse School of Medicine, and Vanderbilt School of Medicine. He volunteered to arrange separate times to meet with internal medicine residents to discuss their career plans and to deliver a presentation describing cardiology fellowship training and mentorship at OSU. These visits occurred over the course of 2008 to 2011 and were well-received by residents, several of whom approached the senior author for further information at the end of each session.

Revise the Interview Day Agenda

The agenda was changed to highlight faculty mentors and fellow achievements, physical facilities, and educational philosophy/environment while tailoring interviews to match clinical and research interests of each applicant. With the goal of better promoting OSU's areas of strength and attracting more competitive URM and non-URM residents, we altered the 2 interview days (on which 25 applicants were seen each day) to emphasize mentorship. The director's opening remarks were expanded to showcase the resources available at OSU, focus retention of fellows as faculty, and describe select faculty areas of interest and the unique opportunities for research and professional growth that they provide. Recent expansion of the faculty allowed us to make interview schedules that were more tailored to applicant career goals. As interviews were arranged, applicants were matched with at least 1 faculty member who had overlapping clinical or research pursuits.

As a supplement to scheduled interviews, a 20-minute open slot was provided for any applicants interested in meeting faculty members who were not on their scheduled agenda for the day. This provided residents with a chance to speak with program or division directors, seek out a person who a residency mentor had suggested they meet, or discuss adjunctive programs mentioned during the morning's welcome remarks. Finally, time was reserved to allow interaction and conversation between URM candidates, current URM fellows, and URM faculty members.

Target Postinterview Communication With Highly Competitive Applicants

Changes in this area involved contacting the most competitive URM applicants at the end of the interview season by phone and letter, reinforcing the program's interest and commitment to provide URM faculty mentorship during training. The MSMP has strict rules regarding how applicants and programs communicate.10 Each side can express interest in each other both during and after the interview as long as they maintain the integrity of the process. The OSU fellowship committee met to review the 50 applicants who were interviewed and then formulated a program rank order list based on each resident's applicant score. Once that was complete, plans were made to call the top 10 ranked applicants with a specific script that expressed OSU's interest but did not violate MSMP rules.

For highly ranked URM applicants, we took an additional step. A personal letter was drafted and sent to each that reiterated the unique strengths of OSU's medical center, division of cardiovascular medicine, and fellowship training program. It also emphasized the community of Columbus, Ohio, as an attractive place for URMs to live and work, noting that many of those in the city's leadership positions are minorities. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, each letter pledged the time and effort of the program and dedicated URM faculty to provide formal, regular, and sustained mentorship during the full course of their fellowship training.

Results

The efforts described in this article were implemented during the winter/spring 2007 MSMP match season and continued over the subsequent 4 match cycles (2008–2011). Class sizes also expanded over that period from 5 entering fellows in 2008 to 6 in 2010, as a result of planned growth (note, however, that 1 first-year student decided to leave the program to return to internal medicine, leaving a current senior class of 4). The 2008 entering class (from the 2007 match) included 1 URM fellow out of 15 (7% of all trainees). Each subsequent entering class included at least 1 additional URM fellow—in 2009, 2 of 15 trainees (13%) were URMs, and in 2010, 3 of 15 trainees (20%) were URMs. In addition, 2 URMs joined the program in 2011 (4 of 16 total trainees [25%]). Finally, in the most recent match for the entering class of 2012, we successfully matched another URM candidate, maintaining a percentage of URM trainees in the program above 20% (of the 4 fellows, all are African American).

In a comparison of ERAS applications from URM and non-URM entering fellows over the past 5 years (including the matched class of 2012), mean USMLE scores were 223 and 230, respectively. When analyzed using a Wilcoxon rank sum test, as the sample sizes were relatively small (n = 6 for URMs, and n = 22 for non-URMs), there was no statistical difference between the 2 groups (P = .39).

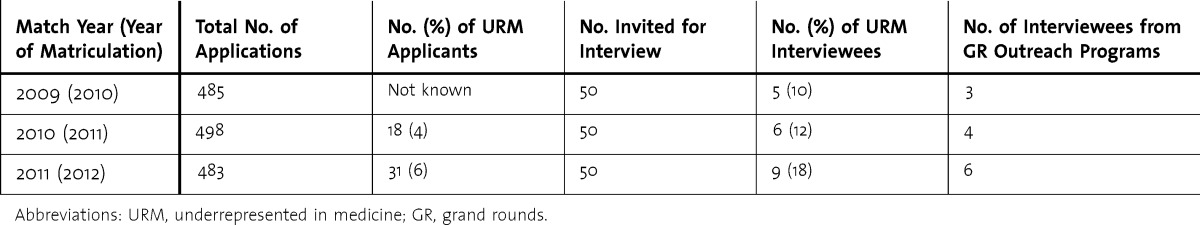

Applicant information from the past 3 match cycles is described in the T a b l e. Specific to the program's grand rounds–based outreach to residency programs with a history of matching URM medical students, there was an increase in all applicants from those programs, culminating in 14 of 483 total applicants (3%) in the 2011 match (Emory = 6, Meharry = 1, Morehouse = 1, Vanderbilt = 5). One was a URM resident, and 2 specifically cited the faculty member's visit as their motivation for applying to the OSU program.

The Importance of URM Faculty

Although our success would not be possible without support from the leadership of the division and fellowship training program and a total group effort from all participating faculty, our experience includes the hard work of a URM cardiologist with a strong interest in diversity and health disparities. This person participated by traveling to promote the program, reviewing fellowship applications, interviewing applicants, and communicating with residents after their interview. Also of importance was the establishment and maintenance of a relationship between our URM fellowship committee member and the fellows. During interview day, this person committed to providing personal mentorship to URM applicants, and has done so with each of the 4 URM fellows since their arrival on campus. He meets with each of them monthly to discuss overall career goals and has mentored them during research projects. Because URM faculty members often face challenges within academic medicine mirroring that of trainees, including limited senior mentorship and disparities in rates of promotion,11–13 this type of time commitment has the potential to become too onerous for 1 faculty member, despite best intentions.

In our experience, attainment of a critical mass of visible URM faculty in the division appeared to be a potential rate-limiting step to attracting URM fellows into the program. This is not to say that efforts to diversify cardiovascular fellowship training programs should have a low priority until the faculty is diversified. Rather, the urgency of diversifying the nation's cardiovascular human resources demands that efforts to diversify academic faculty and fellowship programs proceed in parallel, not in series.

Discussion

The OSU cardiology fellowship training program was able to revise its resident recruitment process to sustainably increase the number of URM trainees in a relatively short time. A concerted effort, focused on making the issue a priority, reaching out to and following up with URM residents, and providing regular support to URM fellows, made this possible. Previous publications have merely been descriptions noting a lack of diversity in various surgical disciplines as it relates to a medical college's efforts to increase the amount of URM students in their population.14–18 Thus far, this article seems to be the first to describe a successful stepwise process to recruit and train more URM cardiology fellows.

A limitation in the description of OSU's intervention is the lack of data on pre-2007 trends in the yearly numbers of URM applicants to the program, the strength of their applications, and the final program rank lists. Another limitation is the absence of data from URM fellows at OSU that establish a clear link between efforts to recruit and fellows' decisions to highly rank our program. The origins for these limitations are multifactorial, and include ERAS maintaining only the most recent year's applications and match results to the program's and fellows' need for confidentiality regarding rank order lists. Other variables may have played a role in URM applicant choices to rank the OSU program, namely a rise in our division's ranking in the U.S. News and World Report hospital rankings19 and the recruitment of several prominent midlevel and senior faculty to leadership positions starting in 2007. The momentum of adding URM fellows in serial years also led to a potentially more attractive makeup of the trainee group, therefore adding another influential variable. Finally, data are lacking quantifying faculty and staff effort (in terms of full-time equivalents) during their participation in addition to faculty perceptions of the intervention.

Another issue may be that we simply made it a priority to rank URM applicants more aggressively than in previous years, thus achieving success in matching them regardless of recruiting efforts, with the implication being that we accepted less competitive applicants in an effort to increase diversity. Although the measurement of an applicant's achievement reflected in his or her application and, by extrapolation, the applicant's potential for being a successful fellow, cannot be fairly quantified, USMLE score comparison shows no significant difference between URM and non-URM fellows matched to the OSU program.

Conclusion

The OSU experience provides a template for other programs interested in improving diversity in a postgraduate medical education program. Although our ability to directly link the interventions to success in attracting high-quality URM applicants to the program has limitations, the results demonstrate that actively making diversity a priority can have positive and sustained effects on the makeup of a cardiology fellowship program.

TABLE.

URM Applicant Information Within the Context of Overall Applicant Pool

Footnotes

All authors are in the Division of Cardiovascular Medicine of the Wexner Medical Center at The Ohio State University. Alex J. Auseon, DO, is Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine and Director of the Cardiovascular Medicine Fellowship Training Program; Albert J. Kolibash Jr, MD, is Associate Professor of Medicine; and Quinn Capers IV, MD, is Assistant Professor of Medicine, Director of Peripheral Vascular Interventions, and Associate Dean for Admissions.

Funding: The authors report no external funding source for this study.

The authors wish to thank Dr. Bill Abraham, Chief, Division of Cardiovascular Medicine; Mary Freeh, division administrator; Ruthie Igo, fellowship coordinator; and the faculty members who make up the fellowship committee for their contributions and support of these efforts.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine, Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yancy CW, Wang TY, Ventura HO, Pina IL, Vijayaraghavan K, Ferdinand KC, et al. The coalition to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in cardiovascular disease outcomes (credo): why credo matters to cardiologists. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(3):245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Association of American Medical Colleges. Diversity in the Physician Workforce. Facts and Figures 2010. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brotherton SE, Etzel SI. Graduate medical education, 2009–2010. JAMA. 2010;304(11):1255–1270. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moy E, Bartman BA. Physican race and care of minority and medically indigent patients. JAMA. 1995;273(19):1515–1520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saha S, Taggart SH, Komaromy M, Bindman AB. Do patients choose physicians of their own race. Health Aff. 2000;19(4):76–83. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.19.4.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. National Resident Matching Program website. www.nrmp.org. Accessed July 12, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mullan F, Chen C, Petterson S, Kolsky G, Spagnola M. The social mission of medical education: ranking the schools. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(12):804–811. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-12-201006150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Association of American Medical Colleges. Electronic Residency Application Service. www.aamc.org/services/eras. Accessed July 12, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10. National Resident Matching Program. Specialties Matching Service Match Participation Agreement. http://www.nrmp.org/fellow/policies/map_sms.html#matchviolations. Accessed July 12, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nivet MA. Minorities in academic medicine: review of the literature. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51(suppl 4):53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahoney MR, Wilson E, Odom KL, Flowers L, Adler SR. Minority faculty voices on diversity in academic medicine: perspectives from one school. Acad Med. 2008;83(8):781–786. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31817ec002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Price EG, Gozu A, Kern DE, Powe NR, Wand GS, Golden S, et al. The role of cultural diversity in recruitment, promotion, and retention of faculty in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(7):565–571. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0127.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vemulakonda VM, Sorensen MD, Joyner BD. The current state of diversity and multicultural training in urology residency programs. J Urol. 2008;180(2):668–672. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andriole DA, Jeffe DB, Schechtman KB. Is surgical workforce diversity increasing. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204(3):469–477. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gebhardt MC. Improving diversity in orthopaedic residency programs. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15(suppl 1):49–50. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200700001-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kane K, Rosero EB, Clagett GP, Adams-Huet B, Timaran CH. Trends of workforce diversity in vascular surgery programs in the United States. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49(6):1514–1519. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rumala BB, Cason FD., Jr Recruitment of underrepresented minority students to medical school: minority medical student organizations, an untapped resource. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(9):1000–1009. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. U.S. News & World Report. Top-ranked hospitals for cardiology & heart surgery. http://health.usnews.com/best-hospitals/rankings/cardiology-and-heart-surgery. Accessed July 12, 2013. [Google Scholar]