Abstract

Background

Ultrasound is a valuable tool in the safe performance of an increasing number of procedures. It has additionally emerged as a powerful instrument for point-of-care assessment by offering internists an opportunity to extend their traditional physical examination.

Objective

This study explored how internal medicine (IM) educators perceive the use of ultrasound for procedures and point-of-care assessments, the extent to which curricula for teaching IM residents ultrasound skills exist, and perceived barriers to teaching its use.

Methods

In February 2012, we administered a 27-question survey to all members of the Association of Program Directors in Internal Medicine, eliciting their opinions about the use of point-of-care ultrasound.

Results

Of 2200 surveys distributed electronically, 234 were returned (a 11% response rate), including 167 by program directors or assistant program directors. Respondents highly rated the usefulness of ultrasound for central-line placement, thoracentesis, paracentesis, and diagnosis of pleural effusions. Evaluation of vena cava and heart, and placement of radial artery catheters received somewhat lower usefulness scores. Forty-five respondents (25%) reported having formal curricula to teach point-of-care ultrasound, and 46 respondents without current ultrasound programs were planning to initiate them in the next 12 months. Potential barriers to teaching and use of ultrasound included the time and cost to train faculty, the cost of ultrasound machines, and the time required to train residents.

Conclusions

Educational leaders in IM view point-of-care ultrasound as a valuable tool in diagnosis and procedures, and many residency programs are teaching these skills to their learners.

Editor's Note: The online version of this article contains the survey instrument used in this study. (Appendix Legends (22.5KB, doc) ) (Appendix 1 (15.1KB, xlsx) ) (Appendix 2 (33.2KB, docx) ) (Appendix 3 (20.5KB, docx) )

Introduction

Ultrasound is a useful tool for enhancing the safety of bedside procedures. The most noted of these is the placement of central venous catheters,1 which in 2001 was listed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality as 1 of 11 key recommendations for improving patient safety.2 Ultrasound use improves the safety and success of many other bedside procedures, including the placement of arterial lines,3 paracentesis,4,5 thoracentesis,6,7 arthrocentesis,8 and the incision and drainage of superficial abscesses.9,10

Point-of-care ultrasound has emerged as a powerful tool for bedside physical assessment. Although the use of ultrasound as a diagnostic instrument by radiologists and cardiologists is well-established, another paradigm has emerged in which clinicians use ultrasound to answer limited point-of-care questions and integrate their findings into their assessment and management, analogous to the use of a stethoscope.11 Emergency physicians were the first to adopt this paradigm, and others have followed, including critical care physicians,11 anesthesiologists,12,13 physiatrists,14 and rheumatologists.15 It has been speculated that ultrasound machines could become the first new diagnostic instrument to be added to the internist's black bag in generations.16

At the same time, relatively little is known about which ultrasound applications internists believe are the most useful, what ultrasound skills internal medicine (IM) residency programs are teaching their trainees, or what barriers may exist to the teaching or use of ultrasound in these settings. Prior experiences have shown that conflicts with traditional imagers,16 liability and risk,16 time constraints,17–19 and credentialing requirements13,19 may be barriers to the teaching and use of point-of-care ultrasound.

We surveyed IM educators to gain a better understanding of their views on the utility of ultrasound for procedures and diagnosis at the point of care and to determine what ultrasound training residents are currently receiving. We also sought to identify barriers to the adoption of point-of-care ultrasound in IM residency programs and clinical practice.

Methods

Setting and Subjects

In February 2012, a 27-question Web-based survey (created using surveymonkey.com) was sent to all 2200 members of the Association of Program Directors in Internal Medicine (APDIM). Members of APDIM include faculty in educational roles (program directors, associate and assistant program directors, and core faculty), program coordinators, fellows, and residents. Three notifications of the survey link were made. Participation was voluntary and anonymous.

Survey

Survey items (provided as online supplemental material) were developed by the authors and tested with the University of Minnesota General Internal Medicine Scholarship Committee, which resulted in the rewording of some unclear questions. The survey included questions about respondents' perceptions of the usefulness of ultrasound for various procedures (central venous lines, arterial lines, paracentesis, and thoracentesis) and for point-of-care evaluations. Responses used a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all useful, 5 = very useful). Participants who identified themselves as program directors were asked about current ultrasound use by their residents and about their program's existing or anticipated future educational efforts to teach ultrasound, including the curriculum's content, duration, timing during residency, and instructors. They were also asked about other residency or fellowship programs at their institution that might teach bedside ultrasound.

The survey also asked respondents to rate potential barriers to the implementation of point-of-care ultrasound curricula using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = no barrier, 5 = very large barrier). For each barrier, an average score for all respondents was calculated. This study was determined to be exempt from review by the University of Minnesota Human Subjects Committee.

Results

Survey Respondents

Of the 2200 surveys distributed to APDIM members, 234 were returned, yielding a response rate of 11%. Among the 234 respondents, 231 indicated their role in a training program. Ninety-eight respondents (42%) were associate program directors, 54 (23%) were program directors, 38 (16%) were other faculty members, and 15 (6%) were assistant program directors. The other 26 respondents (11%) included educational faculty (department chairs and educational chairs) and trainees.

Perceived Usefulness of Point-of-Care Ultrasound by Internists

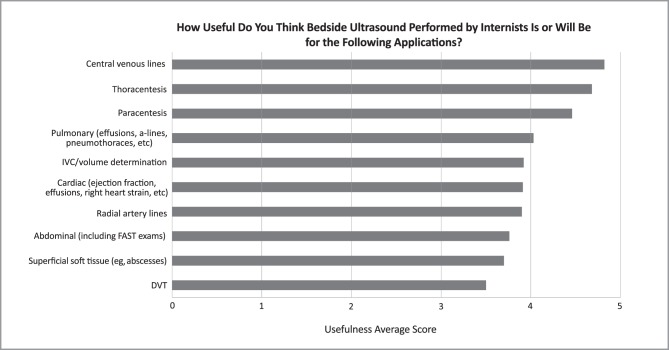

Respondents' average ratings for the usefulness of point-of-care ultrasound for specific procedures and diagnostic applications are shown in figure 1. The mean usefulness scores for procedures ranged from 3.9 to 4.8; scores were highest (indicating greatest usefulness) for central venous lines (4.8), thoracentesis (4.7), and paracentesis (4.6). The mean usefulness scores for diagnostic applications of ultrasound ranged from 3.5 to 3.9; scores were highest for assessment of the lungs (4.0), inferior vena cava (3.9), and heart (3.9).

FIGURE 1.

Perceived Usefulness of Point-of-Care Ultrasound Performed by Internists

The graph depicts average usefulness scores (based on a 5-point Likert scale in which 1 = not at all useful and 5 = very useful) for survey respondents. The number of responses ranged from 231 to 234 for each item.

Abbreviations: IVC, inferior vena cava; FAST, Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma; DVT, deep venous thrombosis.

Current Use of Ultrasound by IM Residents

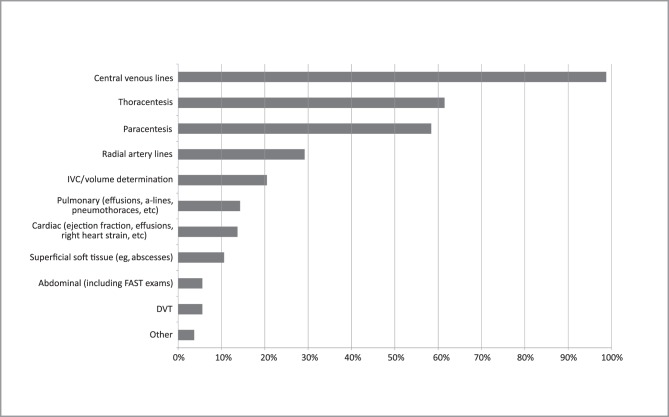

Of the respondents, 161 reported the applications for which residents use ultrasound (figure 2). The greatest use of ultrasound was reported for central venous catheter placement (n = 159; 99%), followed by thoracentesis (n = 99; 61%) and paracentesis (n = 94; 58%). A smaller number of respondents reported that residents currently use ultrasound for diagnostic evaluation.

FIGURE 2.

Current Usage of Point-of-Care Ultrasound by Internal Medicine Residents

The graph depicts the proportion of survey respondents who indicated that residents in their setting currently use ultrasound for a particular application (n = 161 for all questions). Procedural uses of ultrasound are the most common, with a substantially smaller fraction of residents using point-of-care ultrasound for diagnostic applications.

Programs were asked the indication(s) for which residents perform bedside ultrasound; data is the percentage of programs reporting use for the given indication.

Abbreviations: IVC, inferior vena cava; FAST, Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma; DVT, deep venous thrombosis.

Existing and Planned Ultrasound Curricula in IM Residency Programs

Of 177 respondents, 45 (25%) reported that a formal ultrasound curriculum existed at their institution. Of those who did not report having a formal curriculum, 46 (35%) indicated plans to implement one in the next 12 months. Of the respondents indicating a current or planned curriculum, 79 of 84 (95%) reported that they plan to teach ultrasound-guided central venous catheter placement, followed by paracentesis (57 of 76; 75%) and thoracentesis (58 of 78; 74%). Use of ultrasound to evaluate the inferior vena cava was the most commonly taught diagnostic application.

Program directors with current or planned ultrasound curricula reported that an average of 10 hours is or will be spent on didactics and 13 hours in hands-on training. In many cases, training is or will be spread over the course of a residency. Critical care physicians (55 of 72 respondents; 76%) and hospitalists (38 of 66 respondents; 58%) make up a large proportion of the instructors for these courses.

Of 82 respondents, 52 (64%) reported that residents were required to complete training before using ultrasound for procedures. Of the 61 respondents who indicated that diagnostic ultrasound was being taught, 33 (54%) reported that training was required before using ultrasound in diagnosis. Few programs (7 of 80; 8%) retain images to provide feedback to learners.

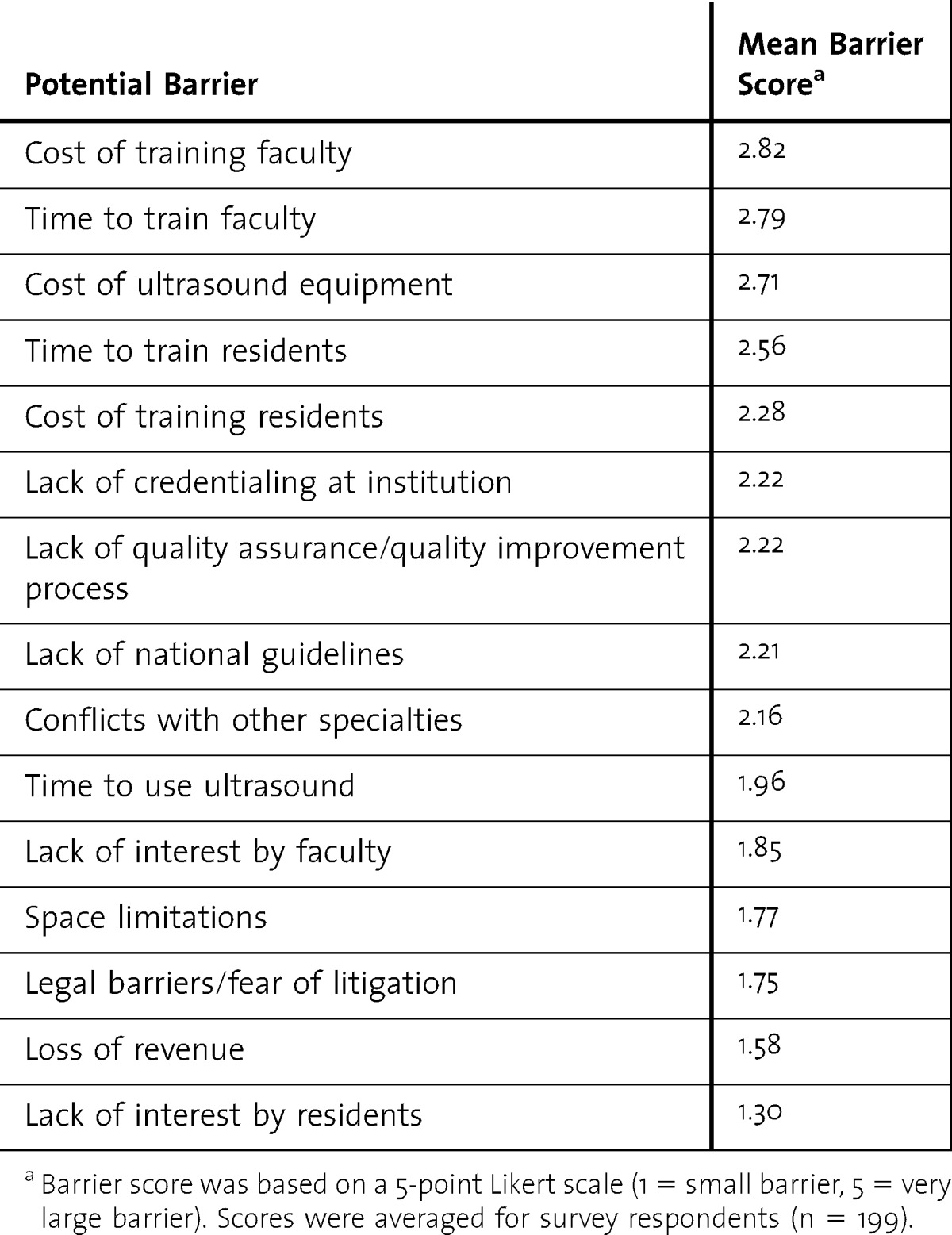

Perceived Barriers to Implementation of Point-of-Care Ultrasound

Mean scores for perceived barriers to teaching and/or implementing point-of-care ultrasound are presented in the t a b l e. Overall, respondents indicated that the cost and time to train faculty members (mean scores = 2.82 and 2.79, respectively) were the largest barriers to implementation.

TABLE.

Perceived Barriers to Implementation and/or Teaching of Ultrasound

Discussion

Our findings show a substantial interest in point-of-care ultrasound among IM educators. Almost all respondents reported that residents use ultrasound for central lines, and many also reported its use in thoracentesis, paracentesis, and other procedures. Many reported that ultrasound could be useful as a point-of-care diagnostic tool. Although only 25% of respondents indicated that their programs currently have formal curricula to teach these skills, others reported plans to implement training within the next year. To our knowledge, this is the first study documenting this interest in the use of ultrasound on a national level.

Our findings suggest that although barriers exist to the implementation of ultrasonography in IM residency training settings, most are perceived to be low to moderate. Respondents indicated that legal barriers and fear of litigation were not major barriers; this finding is consistent with an analysis in emergency medicine, which found only 1 lawsuit related to bedside ultrasonography in more than 20 years of use. This lawsuit was notable, however, in that it was not for misapplication but for failure to use point-of-care ultrasound.20 Lack of interest by residents was not a barrier, which is consistent with a study that indicated there was strong interest in this technology among IM trainees.21

Respondents indicated that residents may be using point-of-care ultrasound to make patient care decisions without any training or quality assurance mechanisms. The American Medical Association has stated that appropriate training and quality assurance/quality improvement are mandatory for users of ultrasound.22 Guidelines for such training and procedures have been developed in emergency23 and critical care medicine,24,25 but to our knowledge none exist for IM. Further collaboration among ultrasound-trained faculty and the establishment of guidelines and standards by governing professional societies may be helpful in facilitating the safe advancement of ultrasound use in IM.

Our study is limited by the survey's low response rate (11% overall and 15% for program directors). The low response rate may be partially explained by the fact that the instructions for the survey asked only program directors and academic internists to complete the survey, thereby excluding many of those receiving it (program coordinators, fellows, and residents). It is possible that respondents were more enthusiastic about the use of ultrasound than nonresponders, and this would limit the generalizability of our results. We also did not pilot test our survey, and it is possible that respondents misunderstood or misinterpreted questions.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated interest in point-of-care ultrasound by IM educators, and an interest in teaching ultrasound skills to IM residents. Further research is needed to determine the ultrasound skills most useful for IM trainees and to develop competency-based curricula as well as quality improvement and quality assurance mechanisms.

Footnotes

All authors are with the Department of Medicine, University of Minnesota. Daniel J. Schnobrich, MD, is Assistant Professor of Medicine; Sophie Gladding, PhD, is Assistant Professor of Medicine; Andrew P. J. Olson, MD, is Chief Resident, Internal Medicine; and Alisa Duran-Nelson, MD, is Assistant Professor of Medicine.

Funding: The authors report no external funding source for this study.

The authors wish to thank the Association of Program Directors in Internal Medicine for permission to use their membership directory, the University of Minnesota Department of Medicine Scholarship Committee for their guidance on administration of the survey and interpretation of results, and Dr Anne Marie Weber-Main for the critical review and editing of manuscript drafts.

References

- 1.Hind D, Calvert N, McWilliams R, Davidson A, Paisley S, Beverley C, et al. Ultrasonic locating devices for central venous cannulation: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2003;327(7411):361. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7411.361. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7411.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shojania KG, Duncan BW, McDonald KM, Wachter RM, Markowitz AJ. Making health care safer: a critical analysis of patient safety practices. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ) (43):i–x, 1–668. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shiloh AL, Savel RH, Paulin LM, Eisen LA. Ultrasound-guided catheterization of the radial artery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Chest. 2011;139(3):524–529. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0919. doi:10.1378/chest.10-0919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nazeer SR, Dewbre H, Miller AH. Ultrasound-assisted paracentesis performed by emergency physicians vs the traditional technique: a prospective, randomized study. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23(3):363–367. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel PA, Ernst FR, Gunnarsson CL. Evaluation of hospital complications and costs associated with using ultrasound guidance during abdominal paracentesis procedures. J Med Econ. 2012;15(1):1–7. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2011.628723. doi:10.3111/13696998.2011.628723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones PW, Moyers JP, Rogers JT, Rodriguez RM, Lee YC, Light RW. Ultrasound-guided thoracentesis: is it a safer method. Chest. 2003;123(2):418–423. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.2.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feller-Kopman D. Therapeutic thoracentesis: the role of ultrasound and pleural manometry. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2007;13(4):312–318. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e3281214492. doi:10.1097/MCP.0b013e3281214492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sibbitt WL, Jr, Kettwich LG, Band PA, Chavez-Chiang NR, DeLea SL, Haseler LJ, et al. Does ultrasound guidance improve the outcomes of arthrocentesis and corticosteroid injection of the knee. Scand J Rheumatol. 2012;41(1):66–72. doi: 10.3109/03009742.2011.599071. doi:10.3109/03009742.2011.599071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Squire BT, Fox JC, Anderson C. ABSCESS: applied bedside sonography for convenient evaluation of superficial soft tissue infections. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(7):601–606. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.01.016. doi:10.1197/j.aem.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tayal VS, Hasan N, Norton HJ, Tomaszewski CA. The effect of soft-tissue ultrasound on the management of cellulitis in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(4):384–388. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.11.074. doi:10.1197/j.aem.2005.11.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kendall JL, Hoffenberg SR, Smith RS. History of emergency and critical care ultrasound: the evolution of a new imaging paradigm. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(suppl 5):S126–S130. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000260623.38982.83. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000260623.38982.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffin J, Nicholls B. Ultrasound in regional anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 2010;65(suppl 1):1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2009.06200.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2009.06200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Desjardins G, Cahalan M. The impact of routine trans-oesophageal echocardiography (TOE) in cardiac surgery. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2009;23(3):263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finnoff JT, Smith J, Nutz DJ, Grogg BE. A musculoskeletal ultrasound course for physical medicine and rehabilitation residents. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;89(1):56–69. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181c1ee69. doi:10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181c1ee69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grassi W, Filippucci E. Ultrasonography and the rheumatologist. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2007;19(1):55–60. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3280119648. doi:10.1097/BOR.0b013e3280119648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alpert JS, Mladenovic J, Hellmann DB. Should a hand-carried ultrasound machine become standard equipment for every internist. Am J Med. 2009;122(1):1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.05.013. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moore CL, Molina AA, Lin H. Ultrasonography in community emergency departments in the United States: access to ultrasonography performed by consultants and status of emergency physician-performed ultrasonography. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47(2):147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.08.023. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dean AJ, Breyer MJ, Ku BS, Mills AM, Pines JM. Emergency ultrasound usage among recent emergency medicine residency graduates of a convenience sample of 14 residencies. J Emerg Med. 2010;38(2):214–220; quiz 220–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.12.028. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eisen LA, Leung S, Gallagher AE, Kvetan V. Barriers to ultrasound training in critical care medicine fellowships: a survey of program directors. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(10):1978–1983. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181eeda53. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181eeda53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blaivas M, Pawl R. Analysis of lawsuits filed against emergency physicians for point-of-care emergency ultrasound examination performance and interpretation over a 20-year period. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30(2):338–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2010.12.016. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kessler C, Bhandarkar S. Ultrasound training for medical students and internal medicine residents—a needs assessment. J Clin Ultrasound. 2010;38(8):401–408. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20719. doi:10.1002/jcu.20719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Medical Association House of Delegates. H-230.960 Privileging for Ultrasound Imaging. http://www.ama-assn.org/resources/doc/PolicyFinder/policyfiles/HnE/H-230.960.HTM. Accessed May 20, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.American College of Emergency Physicians. Emergency ultrasound guidelines. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53(4):550–570. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.12.013. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neri L, Storti E, Lichtenstein D. Toward an ultrasound curriculum for critical care medicine. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(suppl 5):S290–S304. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000260680.16213.26. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000260680.16213.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marik PE, Mayo P. Certification and training in critical care ultrasound. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(2):215–217. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0924-4. doi:10.1007/s00134-007-0924-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]