Abstract

Diabetes mellitus is becoming pandemic, particularly affecting Sub-Saharan Africa, and the prevalence of complications is increasing. Diabetic foot disorders are a major source of morbidity and disability. Delay in the health care process due to patients’ beliefs may have deleterious consequences for limb and life in persons with diabetic foot ulcers. No previous studies of beliefs about health and illness in persons with diabetic foot ulcers living in Africa have been found. The aim of the study was to explore beliefs about health and illness among Ugandans with diabetic foot ulcers that might affect self-care and care seeking behaviour. In an explorative study with consecutive sample semi-structured interviews were held with 14 Ugandan men and women, aged 40-79, with diabetic foot ulcer. Knowledge was limited about causes, management and prevention of diabetic foot ulcers. Foot ulcers were often detected as painful sores, perceived to heal or improve, and led to stress and social isolation due to smell and reduced mobility. Most lacked awareness of the importance of complete daily foot care and seldom practised self-care. Health was described as absence of disease and pain. Many feared future health and related it to contact with nurses in the professional sector from whom they sought information, blood tests and wound dressings and desired better organised diabetes clinics offering health education and more opening hours. Many have an underutilised potential for self-care and need education urgently, delivered in well-organised diabetes clinics working to raise awareness of the threat and prevent foot ulcers.

Keywords: Africans, attitudes to health/illness, beliefs about health/illness, care-seeking behaviour, diabetes mellitus complications, foot ulcer, self-care.

INTRODUCTION

Since diabetes mellitus is growing into a pandemic, particularly increasing in Sub-Saharan Africa, the prevalence of diabetes-related complications is bound to increase [1]. Diabetic foot disorders are a major source of morbidity and disability and thus a significant burden for patients, their families, and society [2-4]. One in six people with diabetes in developed countries is estimated to have an ulcer during their lifetime, and in developing countries it is thought to be even more common [4]. Foot ulcers are more likely to be of neuropathic origin in persons with type 2 diabetes, constituting the majority of diabetes cases of the pandemic, and are highly preventable which is a challenge in the work facing the global diabetes community. Self-care is a cornerstone in this work.

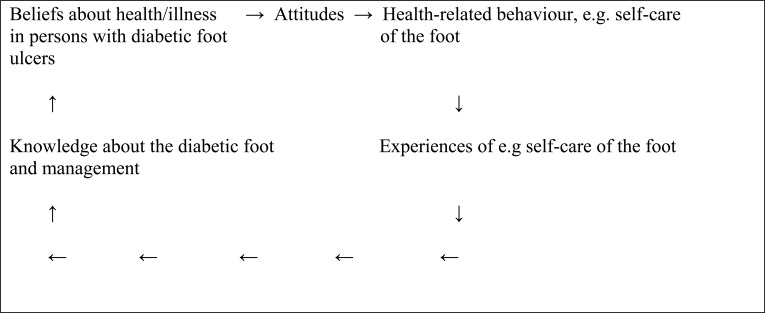

Health-related behaviour, including self-care measures and care seeking behaviour, is determined by individual beliefs about health and illness [5-9] (Fig. 1). Individual beliefs are culturally determined, transmitted through language and learned by socialisation and contact with others in the family, other groups and institutions, e.g. schools, churches, health care institutions etc. [10]. Beliefs are based on knowledge and refined by experience [5]. Delay in the health care process due to beliefs may have deleterious consequences for life and limb in persons with diabetic foot ulcers [4].

Fig. (1).

Our beliefs are ideas about what something is like, based on the knowledge we have. An attitude towards a particular behaviour, e.g. self-care, represents a summation of beliefs about that behaviour and determines the health-related behaviour, for example foot care. Measures taken will lead to experiences that refine the person’s knowledge and thus beliefs and then affect attitudes and behaviour.

Beliefs about health and illness have previously been studied in Ugandans and Zimbabweans with diabetes mellitus [11, 12]. Beliefs affected reported self-care and health care seeking. The respondents had limited knowledge of diabetes and the body, mixed traditional and modern explanations of diabetes, sometimes turned to traditional healers, and seldom practised self-care. A Swedish study, comparing beliefs about health and illness in migrants and Swedes with diabetic foot ulcers [8], showed a similar pattern in non-Swedes. Many of the foreigners had a passive attitude to self-care, perceived foot problems as less serious, and reported a more limited concept of foot care. However, no previous studies focusing on beliefs about health and illness in persons with diabetic foot ulcers living in Africa were found in the literature review.

Diabetes Care in Uganda

In Uganda diabetes care is run in the ordinary healthcare system. Some hospital outpatient diabetes clinics have been developed (World Diabetes Foundation 2008). The one in this study is under the department of internal medicine at a governmental university hospital, with physicians specialised in diabetology (GPs or internists) and non-specialised nurses [13]. The clinic is open one day/week offering consultations for disease control, prescription of drugs, and wound dressings. Sometimes diabetes education (not structured) is delivered by a nurse if time permits. There is no national health insurance system. The government is the main provider of health services free for the users, but health services are underfunded and frequently drugs are unavailable which forces patients to purchase from private pharmacies or from healers in the folk sector [13].

Theoretical Perspectives

Health-related behaviour, including strategies for self-care and health-care seeking, and treatment of disease are related to explanations of disease. An illness could be caused by external or internal factors and the causes could be classified as related to the individual, nature, social relationships and/or the supernatural sphere [14]. Care could be sought from different sectors of society: popular, folk or professional. The popular sector includes family, friends, and relatives. In the folk sector there are people working with sacred or secular healing, and the popular sector includes legally sanctioned health care institutions [15]. It has been proposed that persons in western societies first turn to the popular or the folk sector when needed and in the last resort to the professional sector, and to a higher extent base their illness explanations on factors related to social relationships and supernatural factors in contrast to developing countries where people mainly seek help from the professional sector after initial advice from family and friends in the popular sector, and in the last case turn to the folk sector [14, 15].

Health-related behaviour is also explained by perceived susceptibility to an ill-health condition, perceived seriousness of the condition, outcome expectations in terms of perceived benefits or barriers to specified actions, and efficacy expectations which mean peoples’ conviction about their own ability to carry out a recommended action (self-efficacy) [16], and perceived locus of control including a feeling of being able or not to influence the cause (internal vs external locus of control) [17]. The stronger the self-efficacy is perceived to be, the more active and persistent people are. Successful outcomes increase the degree of self-efficacy [18] and cultural differences may promote different self-efficacy appraisals [19]. Living in paternalistic cultures with high reliance on authorities, e.g. father, teacher or doctor, and in group-oriented societies, as in many African societies where people are dependent on others [20], may foster persons with low self-efficacy [19]. Sociodemographic factors such as age, sex, education, ethnicity and income are believed to influence health-related behaviour indirectly by affecting all the components [16].

MATERIALS AND METHODOLOGY

The Study

The aim of this study was to explore beliefs about health and illness among Ugandans with diabetic foot ulcers that might affect self-care and care seeking behaviour.

Design

A qualitative descriptive study using individual semi-structured interviews for data collection was chosen to reach the individuals’ own beliefs and hereby the patients’ understanding [21] which is important as a basis for self-care and facilitating behavioural changes [22]. Data were collected between October 2010 and February 2011.

Participants

The study population comprised 14 Ugandan men and women, aged 40-79 (Md 69.5 years) living in south-western Uganda, diagnosed with diabetes mellitus (DM) and with a foot ulcer (Table 1). Most were treated with diet and/or oral agents, had a median duration of DM of 7.5 years (range 1-18 years), and had had their foot ulcers a median 1 year, with a variation from 1-4 years. All were peasants and low educated. They originated from an area of the country where 75% of the population live, mostly belonging to the Bantu-speaking group [23].

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Population

| Variable | Ugandan Persons with Diabetic Foot Ulcers N=14 |

|---|---|

| Age 1 | 69.5 (40-79) |

| Gender2 | |

| Female | 10 |

| Male | 4 |

| Duration of DM 1 | 7.5 (1-18) |

| Treatment2 | |

| Diet | 2 |

| Oral agents | 6 |

| Insulin | 2 |

| Combination | 4 |

| Duration of Foot Ulcers 1 | 1(1-4) |

| Complications Related to DM2 | |

| Foot/lower extremity | 14 |

| Retinopathy | 9 |

| Educational Level2 | |

| No education | 8 |

| Primary school | 4 |

| Secondary school | 2 |

| Peasants | 14 |

| Marital Status | |

| Married | 8 |

| Widow | 4 |

| Divorced/separated | 2 |

Values are medians (range).

Values are n.

Inclusion criteria were diagnosis and duration of DM >2 years, present diabetic foot ulcer, and no known psychiatric disorder. Respondents were requested to participate in the study by a nurse working at the surgical ward at a university hospital. Consecutive sampling was used. The principle of saturation guided [21] the number of respondents included in the sample.

Data Collection

A thematised interview guide with open-ended questions including descriptions of common foot problems was used. The interview guide was developed partly on the basis of results from previous studies [7, 8, 24], followed by a review of the literature and discussions with staff at the diabetes clinic. The interview guide explored the following themes in persons with diabetic foot ulcers: 1) beliefs about health and illness, including factors important for health and causes and explanations of the occurrence of foot ulcers and perceived consequences, 2) care seeking behaviours, 3) self-care including advice received and daily foot care. The descriptions included common foot problems related to DM and discussions concerned self-care measures and/or help-seeking as well as the cause of the problem.

The interviews were held in the local language, Runyankore (one of the Bantu languages spoken in most of southern Uganda [23], by a bilingual nurse experienced in surgical care (first author) and not involved in managing the respondents’ diabetes. The interviews were held in a secluded room in the ward, lasted 45-60 minutes, were audio-taped and transcribed verbatim. The interviews were translated into English and then back-translated. The interview started with collecting data on medical and socio-demographic background variables in structured questions (see Table 1), then open-ended questions were posed. The interview guide was pilot-tested in three patients (not included in the study), leading to minor changes in the sequencing and wording of the questions.

Data Analysis

Collection and analysis of data proceeded concurrently, until no new information was added to the categories developed in the analysis [21]. The analysis followed the method described for qualitative interviews by Patton [21]. The aim was to be open to as much variation as possible in the data and thus regularities, patterns, and contradictions were sought. The tapes were listened through directly after the interviews to get a sense of the whole and notes were taken concerning general findings and ideas about emerging themes. By reviewing each line of the texts topics were identified and clustered in the form of categories. The lay theory model of illness causation by Helman [14] and the model for health care seeking behaviour by Kleinman [15] were used as main analytical categories, as previously described [6].

To name categories concepts and terms as close as possible to the text were used. Credibility was ensured by the second author conducting, transcribing and analysing the data [21]. The co-author, a diabetes specialist nurse and experienced researcher in diabetes care, double-checked the content of the categories to confirm their relevance. The confirmability of the study was further ensured by the way the findings are supported by the empirical data: categories followed in the form of literal citations and naming of categories as close as possible to the text. Dependability was ensured by describing the research process as clearly as possible.

Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the Ethics and Review Committee at Mbarara University and the Executive and Principal Nursing Officer at Mbarara University Hospital, Uganda, and was carried out with written informed consent from the respondents, and in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration [25].

RESULTS

In brief the results showed that beliefs about illness and health were mainly related to factors in the individual and nature, combined with social factors and in a few cases with elements of supernatural factors. Help was sought, when needed, in the professional sector, self-care was practiced in a limited extent and the majority of respondents were unaware of the importance of complete foot care. The different themes explored will be described below.

Beliefs About Illness

Most respondents did not know the cause of their foot problems. Some related the foot problems to the duration or condition of the disease while a few talked about external causes such as opening a swelling, their own scratching, overuse of antibiotics or delayed treatment because the wife (a nurse) had treated the wound at home. One perceived it as something natural.

Initially most had detected a painful wound or sores, others had felt irritation or swelling of the foot:

The wound started on a toe…and went to affect the whole foot and the leg. It was so painful that it would not allow me to move…I cannot tell the cause…

(R11).

It started as a small swelling …When the swelling started, I felt mild pain and an urge to scratch it.

(R13).

My wife is a nurse, so she treated me, she delayed taking me back to clinic

(R14).

At the onset of the ulcer the majority thought ‘it would heal’ (R3) or ‘improve’ (R5) and ‘pain would subside’ (R1), another that it ‘would kill’ (R9) him and finally another was ‘confused’ and ‘did not know what to do or where to seek help’ (R12).

All mentioned pain and discomfort due to the smell of foot ulcers, often describing it as a stressful experience, being depressed and feeling useless without any future or worrying for the future. A few related the future outcome to health care professionals:

Stressful. Not allowed to walk. Pain, discomfort due to smell. Change from strong to weak and disgusted with life. No future. Changed life. Worried and not able to provide for family

(R1).

My future depends on the health professionals and on the support I will get from family members

(R6).

Fears were expressed by some concerning social consequences such as poverty by losing one’s job or spouse and becoming social outcasts because of the smell, and individual factors like dying sooner than expected.

When comparing their situation on the day of interview with before the onset of the wound, all informants expressed being ‘disgusted with their lives’, and felt as if the wounds would never heal and they would soon die.

The consequences of the foot ulcers were mainly social and physical with related emotions (individual factors) (Table 2). Most described lost contacts with other people due to smell and thus feeling isolated and dependent on others, and being poor as they were unable to run their business or pay for school fees. Many described feeling disabled because of restricted mobility or being unable to walk. Sleep disturbance and feelings of anxiety, hopelessness, helplessness and lost self-esteem were also described:

Table 2.

Consequences of Diabetic Foot Ulcer

| Illuminative Quotation | Subcategories (n)2 | Main Analytical Category1(n)2 |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| ‘I have even lost my loved ones because of the smell which I cannot control. I feel I am a social outcast’ (R5) | Lost contacts or loved ones due to smell (8) | Social Factors (21) |

| ‘Made my business stick, restricted movement and stigma. The wound have made my life and that of my family a living hell…I feel isolated…’ (R3) | Feeling isolated (6) | |

| ‘Ulcer has caused me a lot of problems because I am now totally dependent on other people who look on me as a burden…’ (R5) | Dependent on others/burden to others (5) | |

| ‘Made my business stick…The wound has made my life and that of my family a living hell. One of my children has dropped out of school. I can no longer afford it.’ (R3) | Poor economy - business stuck, unable to afford school fees (3) | |

| ‘The wound made me anxious because the whole leg will be cut away. I feel disabled…I cannot visit my neighbours…I will no longer perform my usual activities as I used to’ (R6) | Disabled (7) | Individual factors - Physical (20) |

| ‘The wound and the smell have made my life miserable…’ (R4) | Smell (5) | |

| ‘Unable to walk, feel disabled, restricted movement…’ (R1) | Restricted movement/unable to walk (4) | |

| ‘…I no longer sleep at night’ (R8) | Sleep disturbance (3) | |

| ‘Not eating, fear of passing stool as unable to walk to toilet’ (R1) | Not eating - fear of passing stool (1) | |

| ‘The wound made me anxious because I had a feeling that the whole leg will be cut away…’ (R6) | Anxious (2) | Individual factors - Emotional (8) |

| ‘Feeling hopeless, helpless’ (R1) | Hopeless (2) | |

| ‘…helpless’ (R1) | Helpless (1) | |

| ‘Lost self-esteem..’ (R1) | Lost self-esteem (1) | |

Developed from the lay theory model of illness causation by Helman (2007) including four main categories: factors related to the individual, nature, social relations and/or the supernatural world.

n stands for number of statements.

Ulcer has caused me a lot of problems because I am now totally dependent on other people who look on me as a burden. I may not be able to walk normally. I feel disabled. I feel hopeless. I have even lost my loved ones because of the smell which I cannot control. I feel I am a social outcast …

(R5).

Made my business stick, restricted movement and stigma. The wound has made my life and that of my family a living hell. One of my children has dropped out of school. I can no longer afford it. I feel isolated because I barely close my eyes to sleep

(R3).

None of the respondents perceived any advantages of having a diabetic foot ulcer.

Care-Seeking Behaviour and Self-Care

At the occurrence of foot ulcers most respondents had sought help from the professional sector: from nurses or doctors at the hospital, nearby clinic or health worker.

Some stated using self-care measures and bought drugs, e.g. antibiotics, from a drug shop or health centre in the professional sector. In one case a neighbour in the popular sector was consulted to debride a swelling, and one person had sought help from the folk sector by taking herbs.

Went to the nurse…sent for drugs from a drug shop

(R11).

The reason why the foot ulcers started at that moment was unknown to most of the respondents, while some said it was related to supernatural factors and part of ‘God’s plan’, and one person related it to the diabetic disease.

No one can tell why the wound started that moment, may be it was God’s plan

(R7).

The wound started at this moment, maybe the disease has got used to the body

(R8).

Initially when the ulcer occurred, the majority thought it would heal or improve and pain subside. One person thought that it would kill him, and another described being confused.

I thought it would heal with the tablets I bought from nearby drugstore

(R4).

Only one respondent had received advice about daily foot inspections, some claimed to follow advice but lacked advice about complete daily foot care:

When bathing I pay attention to my feet and try to put on shoes daily

(R5).

When foot problems were described it was apparent that cracked heals because of walking barefoot or digging without protective shoes was the most commonly experienced (Table 3). Other common foot problems reported were foot candida, dry skin, decreased sensitivity and irritated skin. A variety of causes of the problems were stated. As regards management of foot problems, the few answers mentioned self-care measures used to a limited extent, mainly drugs for treatment, or seeking help from nurses at health centres or diabetes clinics in the professional sector. Advice about blood glucose control was usual.

Table 3.

Reported Self-Care Measures, Health Care Seeking, and Explanations of the Causes of Foot Problems

| Self-Care Measures Individual Measures a | Nature Cure or Pharmaceutical Measures b | Health Care Seeking Pattern c | Explanations of the Foot Problems |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Foot problem 1: Cracked Heels (9) d | |||

| Cannot avoid | Buying drugs from drug shop | In one case check-ups at diabetes clinic (professional sector) | Bare feet or digging without protecting shoes (5) |

| Avoid walking bare feet | Poor hygiene | ||

| Stone to smoothen foot | DM drugs | ||

| Feet in warm water | DM | ||

| Put on shoes | |||

| Foot problem 2: Foot Candida (6) d | |||

| Protect feet with boots/shoes | Buying drugs from drug shop | In one case treatment at diabetes clinic (professional sector) | Don’t know |

| Foot bath with water and salt | Bare feet | ||

| Rest | Cow dung | ||

| Work environment | |||

| A germ | |||

| DM | |||

| Foot Problem 3: Decreased Sensitivity (6)d | |||

| Warm foot bath, pillows under the feet to raise them | Drugs from drug shop (professional sector) 2 | One person consulting doctor at hospital was referred to a physiotherapist (professional sector) for regular exercise | DM |

| No attention at first, then drugs 2 and advice from nurse at hospital 3 | Three persons went to nurse at health care centre (professional sector) and got advice about checking blood glucose | Level of blood glucose | |

| Advice from nurse at hospital for blood test 3 | Long DM duration | ||

| Decreased blood | |||

| DM drugs | |||

| Foot Problem 4: Dry Skin (6)d | |||

| Rubbing with cream 1 | Cream from drug shop (professional sector) 1 | In two cases consulting nurse at health care centre (professional sector) for blood test and check-ups | Old age |

| Rubbing with Vaseline mixed with local herbs 2 | Vaseline mixed with local herbs 2 (Folk sector) | Don’t know | |

| Poor hygiene | |||

| High temperature | |||

| DM drugs | |||

| DM | |||

| Foot Problem 5: Irritated Skin (5)d | |||

| Self-care with drugs bought in drug shop (professional sector) | In one case consulting nurse at health centre (professional sector) for blood test | Sugar foods, fats, oils | |

| In one case seeking help for check-ups from diabetes clinic (professional sector) | Poor hygiene | ||

| DM | |||

| DM drugs | |||

| Foot Problem 6: Ingrowing Toenails (3)d | |||

| Incision, drainage at home by family member (popular sector) | Antibiotics from drug shop (professional sector) | Don’t know | |

| Problem 7: Indurations (2)d | |||

| Maybe putting on closed shoes | Maybe walking barefoot Don’t know |

||

According to the lay theory model of illness causation (Helman 2007) these measures were categorised as belonging to the individual sphere

and nature.

According to the model of health care seeking patterns

Kleinman 1980), health care may be sought either in the professional, popular or the folk sector. The professional sector includes the legally sanctioned healing professions, such as western scientific medicine or biomedicine. The popular sector comprises non-professionals in the family, friends and/or relatives. The folk sector includes certain persons, often termed folk healers, specialised in different forms of healing (sacred or secular).

Number in parentheses = n reporting the problem.

refer to the text in different columns to connect the text.

Complete daily foot care was practised by just one person:

I wash my feet daily, I keep my nails short, ensure no injury is inflicted on the skin while cutting nails I put on cotton socks to reduce moisture and always keep spaces between toes, I clean and dry them

(R3).

Two persons had changed their daily foot care practice, having become aware of the importance of foot care, either from having had a wound and being taught by health professionals (professional sector) or having received advice from a neighbour (popular sector):

Before, wash daily with soap, clean cloth but not paying attention to the feet. Wound developed, use of warm water. Hospital care, nurses taught: When bathing pay attention to feet. To put on shoes

(R1).

I used to wash my whole body with soap and clean cloth without paying attention to my feet. I was advised by my neighbour to use …salt in warm water

(R2).

However, the majority were unaware of the importance of complete daily foot care and most described washing with soap, salt and water, and a few talked about washing daily. Some discussed washing while bathing or washing as with any other part of the body. One person talked about putting on shoes.

I use water, sponge and soap I wash every part using the same friction. I had never thought of paying attention to the feet

(R11).

When it is time for me to take a bath, I wash my whole body including the feet

(R12).

Respondents had with one exception (using herbs), not used complementary alternative medicine measures or natural remedies for self-management of the feet, and none claimed that religion was important for their wound management.

Beliefs About Health

Health was described as having ‘no disease or no pain’ (individual factors), which some combined with being able to do daily duties or being able to work, walk and eat (individual and social factors):

When one is able to work and eats plus absence of the disease or being in no pain

(R4).

Some respondents considered the importance of instrumental tangible support from health care staff in terms of drugs and regular glucose monitoring but did not receive as it was not free:

The wound has made me very poor. I expected help from health care staff, especially drugs and regular glucose monitoring, but nothing was given to me… I was advised to constantly check my blood glucose but it is not possible …each time you check that is money which I don’t have

(R11).

The majority of the respondents stated they did not know whether it is possible to prevent diabetic foot ulcers, while some thought it was possible but did not explain how.

About half of the respondents discussed factors that could influence wound healing such as use of shoes, daily foot care and taking prescribed medications.

Factors mentioned as harmful or having a negative influence on health were social factors, such as feelings of stigma and discrimination, and loss of loved ones because of the smell and strained economy due to expensive drugs.

I have even lost my loved ones because of the smell which I cannot control. I feel I am a social outcast

(R5).

In order to feel well and experience good health most respondents discussed the importance of contact with health care staff in the professional sector for control of blood glucose at the diabetes clinic, wound dressings by nurses, and getting advice (social factors). Some relied on prayer (supernatural factor) and one talked about money to be able to join the diabetes association (social factor).

Dressings made by nurses. Checking the state of glucose level is so important because it helps the doctors review the management

(R2).

I pray not to get more complications which may worsen my already disgusting life. Where hope is left is in the hospital because when I go for check-ups in the diabetic clinic, I get counselling from the nurses and doctors. In the clinic I rarely receive drugs but at least the nurses care for us in all ways and one leaves the clinic happy

(R5).

Most respondents talked about their future health generally in negative terms and said they had no future or worried about the future. A few related the future to health care professionals and one did not think about the future at all:

Stressful. Not allowed to walk. Pain, discomfort due to smell. Change from strong to weak and disgusted with life. No future. Changed life. Worried and not able to provide for family

(R1).

My future depends on the health professionals and on the support I will get from family members

(R6).

The majority of respondents perceived that the wound would be long lasting either ‘forever’ (R?) or ‘for a long time’ and one said ‘I have no hope’ (R?).

Also the health care organisation is of importance for health. Most of the respondents said that ‘nurses and doctors’ were responsible for their care, some were more specific and added enrolled nurses and doctors:

Doctors work with the nurses, mainly senior enrolled nurses

(R5).

Some demonstrated their uncertainty by not specifying at all and instead talked about ‘health professionals’, and one about ‘nurses’.

The patients perceived that what health care staff wanted to change in the care delivered at the diabetes clinic was predominantly working with health information and having time for it. Some talked about outreach centres to deliver service nearer to people, a few desired increased staff or number of days for the diabetes clinic, and one desired free treatment.

I wish nurses could make time and educate the patients

(R9).

…to take service nearer to people, a clinic could be set up on every health centre. Increased number of staff

(R5).

To increase number of days for diabetic clinic, instead of being once a week it could be three times in a week

(R12).

As regards the patients’ perceptions of how good care for persons with diabetic foot ulcers should be organised, the attitude was important to them, with communicating/informing staff, patient-centered with committed nurses and other health professionals and staff having a common goal of patient satisfaction. Social factors pointed out were, firstly, the need for cheap and available drugs from the diabetes clinic and free hospital treatment, and secondly, daily foot care, including cleaning and treatment, delivered by qualified staff and in separate wards for those with dressings to be made.

Nurses should be committed and knowledgeable about the condition. Nurses and other professionals should have one goal and that is to create patient satisfaction

(R9).

To be able to get food and drugs that are not costly from diabetes clinic

(R1).

Patient should be treated and cleaned daily. Patients with diabetic foot ulcers should be nursed in a separate ward

(R11).

DISCUSSION

This study is unique as no previous investigations have been found focusing on beliefs about health and illness in patients with diabetic foot ulcers living in Africa. The main results showed limited knowledge about the causes, management and prevention of diabetic foot ulcers, often detected as painful sores perceived to heal or improve. The foot ulcer often led to stress, social isolation due to smell and reduced mobility. Most lacked awareness of the importance of complete daily foot care, including protection of the foot, and self-care was practised to a limited extent. Health was described as absence of disease and pain, many expressed fear about future health, and related health to contact with nurses in the professional sector whom they consulted to check blood glucose, dress wounds and obtain information. Patients desired a better organised diabetes clinic particularly for offering health education, cheap and available drugs, and longer opening hours.

Beliefs about health and illness were mainly related to factors in the individual and nature, combined with social factors and in a few cases with elements of supernatural factors. Help was sought, when needed, in the professional sector. Thus, the respondents did not show behaviour similar to that described in non-westerners by the models chosen for analysing data [14, 15]. It has been suggested that non-westerners more likely focus on the social and supernatural spheres, first contacting family, friends, or relatives in the popular sector and then traditional healers in the folk sector. This is in contrast to westerners, who emphasise factors in the individual or nature and consult the professional sector in case of problems. As in our previous studies of Swedes and migrants with diabetic foot ulcers living in Sweden [8] and Ugandans with diabetes mellitus [11] the results do not correspond to the theoretical models used [14, 15]; beliefs therefore need to be recognised as being individual.

Another Ugandan study investigating health care seeking behaviour among persons with diabetes found that many, particularly women, sought help from traditional healers if they felt health care had failed to help them [13] but the contrary was indicated here as many consulted nurses at the diabetes clinic in the professional sector and desired longer opening hours to get health education and help.

At the onset of the foot ulcer most respondents in this study reported having detected painful sores and skin irritations perceived to heal or improve and of unknown cause, and some had a fatalistic view, relating the sore to supernatural factors (God’s will) beyond their own control. They had a low awareness of the seriousness of the condition [16] and an external locus of control [17]. Persons who do not feel they have control over their health, as in this study, are less likely to carry out self-care measures and health-related behaviours [16, 27].

Detection of painful ulcers at the onset of the foot problems, despite shorter diabetes duration, in respondents in this study was in contrast to data from the previous study of Swedish- and foreign-born persons with diabetic foot ulcers living in Sweden (7.5 and 27 vs 18 years median) who reported problems with early detection of the foot ulcers because of decreased sensitivity and thus, many found an ulcer by regular foot inspection [8]. The difference might indicate later detection and deeper, more serious ulcers activating also the deeper pain systems [3, 28] among Ugandans. As previously concluded, small signs of foot problems might have gone unnoticed [3]. The difference can also be related to behavioural factors in the patient, e.g. expectations to express pain when having detected an ulcer, or different degrees of seriousness related to the causes of the ulcers [3], which seemed to be caused by external causes such as walking barefoot and working without protective shoes. Walking barefoot is a common practice in rural Africa, commonly related to low income (purchase of appropriate footwear might not be feasible or of high priority) but may be cultural as well [3]. Taken together with the findings of reported foot problems (mainly cracked heels, dry and irritated skin), practising self-care to a limited extent, and with few exceptions being unaware of how complete daily foot care should be practised and demonstrating lack of knowledge about how to prevent diabetic foot ulcers, clearly indicates limited knowledge about the diabetic foot and management of the foot among the respondents. Poor self-care has previously been shown to be an important risk factor for diabetic foot ulcers in Kenya [29], and age, low educational level and low socioeconomic status influence awareness of diabetic foot risks [30] and thus health-related behaviour [16].

Having a foot ulcer was perceived by respondents in this study as a stressful, depressing experience because of pain and feelings of fear for the future, as found in European diabetic populations [8, 31]. It is important for health professionals to assess and deal with patients’ emotions to prevent consequences like stress-related hyperglycaemia which impairs the wound healing [32, 33]. It is also important to detect feelings of fear for the future as it is a realistic feeling as diabetic foot complications in Africa generally are associated with considerable long-term disability due to amputations and premature mortality [3]. A previous investigation from Tanzania showed mortality rates >50% among patients with severe foot ulcers, who did not undergo surgery [34]. Physical treatment of the ulcer is imperative, but psychological components are also important to deal with to offer holistic care supporting complete adaptational strategies to cope with the foot problems [8, 27].

In contrast to our previous Swedish investigation [8], it is worth noticing that respondents in this study did not state any advantages of having the ulcers; instead they described negative consequences such as social isolation due to reduced mobility and smell. Smell was not perceived as a problem in the Swedish study [8] but has been described in other investigations [3, 31] and can be related to identified care inadequacies in relation to diabetes in Africa, such as poverty, unaffordable medicines and dressings, lack of resources, and unhygienic conditions [2, 35].

The sample included a higher proportion of women than men, which could be seen as a bias, but the prevalence of diabetes mellitus has increased in women of reproductive age. Due to differences in life expectancy there are more women than men with diabetes in older age groups [26].

As regards demographic characteristics the sample included low-educated peasants and is thus similar to the general population of Uganda, with most having occupations of low socioeconomic status, but differing as most have an educational level from secondary school [23], which limits the results. However, the studied group is a risk group for foot ulcers [3] and previous studies of beliefs about health and illness in low-educated Ugandans with DM confirm limited DM knowledge [11].

Findings from qualitative studies have limited generalizability, but if appropriately conducted and carefully analysed the results are transferable to other groups with similar characteristics [21]. However, data from a qualitative study are intended to give a deeper understanding of the individuals situation and not to explain and draw general conclusions from.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, most respondents did not practise self-care as they lacked knowledge about the causes of diabetic foot ulcers as well as preventive measures and management and thus were unaware of the seriousness of the condition. Health was described as absence of disease and pain; many expressed fears for future health and related health to contact with health care staff and desired development of the diabetes clinic offering accessible health education and affordable drugs. Many have an underutilised potential for self-care management and need to be supported with diabetes education urgently to become aware of the threat and how to prevent it. Well-organised care, identification of the at-risk foot, and education do not require any expensive equipment and can make a clear difference in the outcome of diabetic foot ulcers [2].

Respondents in this study stated that having no disease or pain and regular contact with health care staff for blood control, wound dressings and teaching were important for their health. They also expressed fears for future health but practised self-care to a limited extent. As in our previous Swedish study of beliefs about health and illness in persons with diabetic foot ulcers, the patients are an underutilised resource in the prevention and management of diabetic foot ulcers [8]. However, they can and should be activated and their wish for a better organised diabetes clinic with higher accessibility and particularly focused on offering health education need to be supported. Education is the most important preventive tool in Africa and should include simple and repeated advice targeted at both healthcare workers and patients [2, 3, 36, 37]. Education should be tailored to the patients’ beliefs, understanding [2, 8] and social background [2] and aimed at developing awareness of the seriousness of the condition [8].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Ms Fortunate Atwine, lecturer at the Department of Nursing, Mbarara University of Science and Technology (MUST), Uganda, and Dr. Björn Albin, associate professor, School of Health and Nursing Sciences, Linnaeus University, Växjö, Sweden, for helpful criticism and stimulating discussions.

This work was supported by grants from The Linnaeus-Palme Foundation, Swedish International Development Aid, Sweden, which enabled joint international collaboration in Sweden and Uganda.

ABBREVIATION

- DM

= Diabetes mellitus

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Hjelm K: Conception and design of the study, data analysis and interpretation of results; drafting and preparation of the manuscript for publication.

Beebwa E: Conception and design of the study, data collection, analysis of data and interpretation of results; drafting and final approval of the manuscript for publication.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mbanya J, Matala A, Sobngwi E, Assah F, Enoru S. Diabetes in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet. 2010;375(9733):2254–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60550-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boulton A, Vileikyte L, Ragnarsson-Tennvall G, Apelqvist J. The global burden of diabetic foot disease. Lancet. 2005;366:1719–24. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67698-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abbas ZG, Archibald LK. Epidemiology of the diabetic foot in Africa. Med Sci Monit. 2005;11(8):262–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakker K, Schaper NC. The development of global consensus guidelines on the management and prevention of the diabetic foot 2011. Diabetes Metab. 2012;28(1):116–8. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glanz K, Rimer B, Lewis F. Health Behaviour and Health Education. Theory, Research, and Practice. 3rd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hjelm K, Nyberg P, Isacsson Å, Apelqvist J. Beliefs about health and illness essential for self-care practice: a comparison of migrant Yugoslavian and Swedish diabetic females. J Adv Nurs. 1999;30(5):1147–59. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hjelm K, Nyberg P, Apelqvist J. Gender influences beliefs about health and illness in diabetic subjects with severe foot lesions. J Adv Nurs. 2002;40(6):673–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hjelm K, Nyberg P, Apelqvist J. The influence of beliefs about health and illness on foot care in diabetic subjects with severe foot lesions: a comparison of foreign-and Swedish-born individuals. Clin Effect Nurs. 2003;7:3–14. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hjelm K, Bard K, Nyberg P, Apelqvist J. Beliefs about health and diabetes in men with diabetes mellitus of different origin living in Sweden. J Adv Nurs. 2005;50:47–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berger P, Luckmann T. The social construction of reality. A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. London: Penguin Books; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hjelm K, Nambozi G. Beliefs about health and illness: a comparison between Ugandan men and women living with Diabetes Mellitus. Int Nurs Rev. 2008;55(4):434–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2008.00665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hjelm K, Mufunda E. Zimbabwean Diabetics’ beliefs about health and illness: an interview study. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2010;10(7):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-10-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hjelm K, Atwine F. Health-care seeking behaviour among persons with diabetes in Uganda: an interview study. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2011;26(11):11. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-11-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Helman C. Culture, Health and Illness. London: Butterworth & Co (Publishers), Ltd; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kleinman A. Patients and healers in the context of culture. London: University of California Press, Ltd; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH. Social learning theory and the health belief model. Health Educ Quart. 1988;11:403–18. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rotter JB. Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychol Monogr. 1966;80(1):1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bandura A. Exercise of personal and collective efficacy in changing societies. In: Bandura A, editor. Self-Efficacy in Changing Societies. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1995. pp. 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oettingen G. Cross-cultural perspectives on self-efficacy. In: Bandura A, editor. Self-Efficacy in Changing Societies. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1995. pp. 149–76. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hofstede G. Culture’s consequences: international differences in work-related values. London: Sage Publications; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patton MQ. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed. London: Sage; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stuart L, Wiles PG. A comparison of qualitative and quantitative research methods used to assess knowledge of foot care among people with diabetes. Diabetes Med. 1997;14(9):785–91. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199709)14:9<785::AID-DIA466>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.SIDA. Landguiden Uganda, Afrika; 2007. (Country Guide to Uganda, Africa) Available from: http://www.landguiden.se/pubCountryText.asp?country_id=178&subject_id=0 . [Cited: 2012 September 15].

- 24.Hjelm K, Nyberg P, Apelqvist J. The diabetic foot - multidisciplinary management from the patient’s perspective. Clin Effect Nurs. 2002;6:66–77. [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Available from: http://www.wma.net/e/policy/b3.htm . 2008. [Cited 2012 September 8].

- 26.IDF. International Diabetes Federation. Diabetes Prevalence. Diabetes Atlas, 3rd edition, Montreal. Available from: http://www.diabetesatlas.org/content/what-is-diabetes . 2009. [Cited 2012 August 15].

- 27.Przybylski M. Health locus of control theory in diabetes: a worthwhile approach in managing diabetic foot ulcers? J Wound Care. 2010;19(6):228–33. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2010.19.6.48470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot. International Consensus on the Diabetic Foot. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Nyamu PN, Otieno CF, Amayo EO, McLigeyo SO. Risk factors and prevalence of diabetic foot ulcers at Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi. East Africa Med J. 2003;80(1):36–43. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v80i1.8664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lamchabab FZ, El Kihal N, Khoudri I, Charibi A, Hassam B, Ait Ourhroui. Factors influencing the awareness of diabetic foot risks. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2011;54(6):359–65. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ribu L, Wahl A. Living with diabetic foot ulcers: A life of fear, restrictions, and pain. Ostomy/Wound Management. 2004;50(2):57–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vileikyte L. Stress and wound healing. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25(1):49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Broadbent E, Petrie KJ, Alley PG, Booth TJ. Psychological stress impairs early wound repair following surgery. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(5):865–69. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000088589.92699.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abbas ZG, Archibald LK. Foot complications in diabetes patients with symptomatic peripheral neuropathy in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Diab Int. 2000;10:52–56. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whiting DR, Guariguata L, Weil C, Shaw J. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2011 and 2030. Diab Res Clin Pract. 2011;94(3):311–21. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gill GV, Mbanya JC, Ramaiya S, Tesfaye S. A sub-Saharan African perspective of diabetes. Diabetologia. 2009;52:8–16. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1167-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bakker K, Apelqvist J, Schaper NC. Practical guidelines on the management and prevention of the diabetic foot 2011. Diabete Metab. 2012;28(Suppl 1):225–31. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]