Abstract

We collected anophelines every second week for one year from randomly selected houses in southwestern Ethiopia by using Centers for Disease Control (CDC) light traps, pyrethrum spray catches, and artificial pit shelter constructions to detect circumsporozoite proteins and estimate entomologic inoculation rates (EIRs). Of 3,678 Anopheles arabiensis tested for circumsporozoite proteins, 11 were positive for Plasmodium falciparum and three for P. vivax. The estimated annual P. falciparum EIR of An. arabiensis was 17.1 infectious bites per person per year (95% confidence interval = 7.03–34.6) based on CDC light traps and 0.1 infectious bites per person per year based on pyrethrum spray catches. The P. falciparum EIRs from CDC light traps varied from 0 infectious bites per person per year (in 60% of houses) to 73.2 infectious bites per person per year in the house nearest the breeding sites. Risk of exposure to infectious bites was higher in wet months than dry months, with a peak in April (9.6 infectious bites per person per month), the period of highest mosquito density.

Introduction

Although recent trends show a reduction in the prevalence of malaria in Ethiopia, it is still a challenge to the health of many communities.1 Long-lasting insecticidal treated nets (LLINs) and indoor residual spraying (IRS) are the two main malaria vector control tools being used to decrease mosquito density and longevity, and human–vector contact of Anopheles arabiensis, the species responsible for > 95% of malaria transmission.2 The impact of LLINs and IRS on indoor populations of vectors is to reduce entomologic transmission indicators, the most common of these is the entomologic inoculation rate (EIR), which is the product of sporozoite rate and human biting rate over a defined time and space,3 parity (longevity), sporozoite rates, and human blood index.4 The success of both interventions depends on the response of vectors,5 their behavior and interaction with humans, and alternative hosts.6,7

The EIR measures the intensity of malaria transmission in a particular area.3 Estimation of the EIR is important for quantifying the potential level of human exposure to infected mosquitoes and for assessing the impact of interventions on malaria transmission in a given area.4,8 Many studies have reported huge variations in malaria transmission intensity in Africa,9 not only between urban and rural settings but even within the same locality.10 It has been reported that the EIR varies between 0.01 and 1000 infectious bites per person per year (ib/p/year) in malaria-endemic countries in Africa.11

The human landing catch (HLC) has been the most widely accepted method for estimating the human-biting rate12 because it measures actual human–vector contact, but it has obvious ethical and technical problems.13 Other methods such as the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) light trap have been evaluated to replace the HLC by calibrating and determining an index equivalent to the human biting rate. It is believed that CDC light traps when set near sleeping persons protected by nets capture the anthropophilic mosquito species and thus can provide an indirect estimate of the human biting rate.13 Some investigators have also used pyrethrum spray catches (PSCs) to determine the human biting rate, although this method might underestimate the human–vector contact and consequently the intensity of malaria transmission because many indoor-fed mosquitoes will leave houses before and during spraying.7 In this study, CDC light traps and PSCs were used to estimate the EIR.

In Ethiopia, few attempts have been made to estimate EIR despite the fact that two-thirds of the country is malarious. However, several reports are available on sporozoite rates of An. arabiensis from different localities.2,14 Based on microscopic dissection, Krafsur15 in 1977 working in the low-lying and highly malarious town of Gambela and riverside villages in western Ethiopia, was the first to estimate an annual EIR of An. gambiae s.l. (presumably An. arabiensis). It was not until 36 years later that further estimation of EIR in Ethiopia was published for highland villages with unstable malaria transmission in the south-central region of the country.16 Thus, there are substantial gaps in knowledge regarding entomologic transmission levels and the impact of the current anti-vector operations (IRS and LLINs).

Malaria is clearly a public health problem in Chano village in southwestern Ethiopia.17 In the absence of entomologic information on malaria transmission in this village and the surrounding areas, a detailed longitudinal entomologic study was conducted to study host preferences, insecticide susceptibility, anopheline diversity, seasonal variations, and intensity of malaria transmission (EIR). Anopheles arabiensis has developed resistance to the pyrethroid insecticides and DDT, and showed a greater tendency to feed on cattle than humans, with an overall human blood index (HBI; the proportion of the An. arabiensis fed on human blood meals of the total blood meals determined) of 44% and a bovine blood index of 69%.18 We report anopheline species diversity, monthly variations of An. arabiensis in relation to meteorologic variables, variations between houses in relation to distance from breeding sites, and malaria transmission indices of sporozoite rates and EIR.

Materials and Methods

Study area.

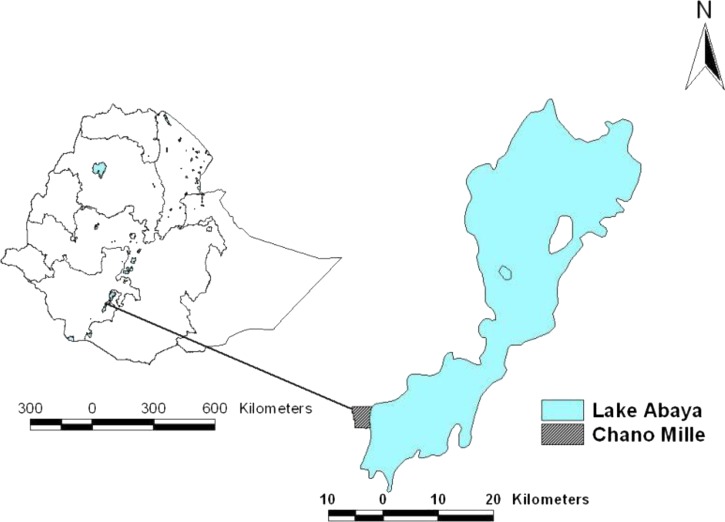

The study was conducted in Chano (Figure 1), which is north of Arba Minch during May 2009–April 2010. The health post, which is at the center of the village, is located at 6°6.666′N, 37°35.775′ E and at an altitude of 1,206 meters above sea level. For the purpose of epidemiologic study, the village was divided in to three sub-villages and coded as sub-village 01, 02 and 03. A detailed description of the study area has been reported elsewhere.18

Figure 1.

Location of the study site in Chano village, Ethiopia.

Monthly meteorologic data were recorded from the weather station at Arba Minch University, which is 6 km from the study area. In common with most areas in the southern Ethiopian Rift Valley,19 there were two wet seasons with the main rains falling during March–May and a smaller rainy season during October–December; the dry seasons are during June–September and January–February. Because of high surface water, we classified November 2009 as a wet month despite the low rainfall recorded.

Mosquito sampling.

Thirty houses from the three sub-villages were selected for mosquito collections. The selected houses were distributed on the periphery and in the middle of each sub-village and equally divided for sampling by using CDC light traps (10 houses), PSCs (10 houses), or artificial pit shelters (10 houses). The distance from the main larval breeding sites to each house was recorded by using a global positioning system (GPS 60™; Garmon, Olathe, KS).

Anopheles mosquitoes were sampled every second week for 1 year (May 2009–April 2010). Before mosquito collection, verbal consent from the head of each household was obtained. Indoor host-seeking Anopheles were collected from 6:30 pm to 6:00 am in 10 houses by using CDC light traps by hanging them 45 cm above the floor at the feet of sleeping persons, who were protected by untreated mosquito nets.13 Other occupants in the houses were left to use LLINs provided by the Ministry of Health as part of the routine malaria control. Two trained field assistants from the community turned the light traps on and off at 6:30 pm and 6:00 am, respectively. In the mornings, collection bags were transported to the entomology laboratory at Arba Minch University for sorting and further processing.

Indoor-resting mosquitoes were sampled in the mornings (6:00 am to 9:00 am) from 10 other randomly selected houses by using the PSC technique. All food items and small animals were removed from houses, and all openings and eaves of windows and doors were closed with pieces of cloth. Finally, the floor and furniture were covered with white sheets before spraying houses with a pyrethroid roach killer aerosol (registration no. ET/HHP/130M/S, Kafr; EI Zayat, Egypt). Ten minutes after spraying, anophelines that had been knocked down were collected by using forceps, paper cups, and a torch light. The number of occupants who had slept in each house the previous night was recorded.

Outdoor-resting mosquitoes were collected by using a handheld mouth aspirator, paper cup, and torch from the pit shelters constructed under the shade of mango trees in the compound of each of the 10 houses. Each shelter was 1.5 m deep and had an opening of 1.2 m × 1.2 m. Approximately 0.5 meters from the bottom of each pit shelter, a 30-cm horizontal deep cavity was prepared in each of the four sides.20 During the collection period (6:30 am–10:00 am), the mouth of each pit shelter was covered with an untreated bed net to prevent mosquitoes from escaping.

Anopheles mosquito processing.

Female Anopheles mosquitoes were killed by freezing, identified to the species level by using a morphologic key,21 and classified into unfed, freshly fed, half-gravid, and gravid.12 The abdomens of unfed An. arabiensis, the only member of the An. gambiae complex in the area,18 were dissected for parity based on the method of Detinova.22 The remaining parts of parous and other specimens of Anopheles were preserved individually in vials with silica gel for detection of circumsporozoite protein (CSP).

Detection of CSP.

The head and thorax of female Anopheles were tested for the CSPs of Plasmodium falciparum, P. vivax 210, and P. vivax 247 by enzyme-linked immunoabsorbent assay (ELISA).23 All positive samples were re-tested for confirmation.

Data and statistical analysis.

Data were entered and analyzed by using SPSS version 19 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The sporozoite rate was calculated as the proportion of mosquitoes positive for P. falciparum and P. vivax of the total number of mosquitoes tested. Parity rate was determined as the proportion of parous mosquitoes over the number of total mosquitoes dissected.

Analysis of variance was used to compare the monthly total and the house density of An. arabiensis. Tukey's honestly significant difference (HSD) test was used to distinguish the months and the houses with the maximum mean density of mosquitoes. Log-transformed data were used for statistical analysis. The Spearman's rho correlation was used to test the relationship between mean monthly density of mosquitoes and EIR with rainfall. All tests were performed at a 0.05 significance level.

The annual P. falciparum and P. vivax EIR of An. arabiensis was calculated from CDC light traps by using the standard method, 1.605 × (no. circumsporozoite-positive ELISA results from CDC light trap/no. mosquitoes tested) × (no. mosquitoes collected from CDC light trap/no. catches) × 365 days, and the alternative method, 1.605 (no. positive ELISA/no. catches) × 365 days.24 The monthly EIR was determined as a product of the EIRs for each day of the month.

The EIR was also estimated from the PSC as described by the World Health Organization25 by using the formula: (human-biting rate) × (CSP rate). The human-biting rate was calculated by dividing the total number of freshly fed An. arabiensis caught by PSC by the total number of occupants who slept in the houses the night before collection and multiplied by the HBI. The HBI was calculated as the proportion of Anopheles mosquitoes that fed on humans (including mixed blood meal origins) of the total Anopheles analyzed for blood meal origin.26 Results of the HBI have been reported elsewhere.18

Results

Species composition.

Overall, 4,708 anopheline mosquitoes belonging to 16 species were collected and identified. Of the 16 species collected, 14 species were obtained from CDC light traps (n = 2,506), 12 species from pit shelters (n = 1,678), and 9 species from PSCs (n = 524). Anopheles arabiensis accounted for 89% of the mosquitoes from CDC light traps, 83.4% from the PSCs, and 63.0% from pit shelter collections. The next most abundant species was An. marshalli, which accounted for 9.1% of mosquitoes caught in CDC light traps, 13% in PSCs, and 31.3% in pit shelters (Table 1). Using CDC light traps as a reference, we found that the catch ratio of PSCs to CDC light traps was 0.2 and that of pit shelters to CDC light traps was 0.67 for all anophelines. The figures for An. arabiensis were 0.2 for PSC and 0.47 for pit shelters, and the respective values for An. marshalli were 0.29 and 2.3. Further analyses were then performed on samples of An. arabiensis.

Table 1.

Anopheles spp. mosquitoes collected in Chano in southwestern Ethiopia, by using different collection methods during May 2009–April 2010*

| Species | Collection methods | Total no. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDC light trap, no. (%) | PSC, no. (%) | Pit shelter no. (%) | ||

| Anopheles arabiensis | 2,230 (89) | 437 (83.4) | 1,057 (63) | 3,724 (79.1) |

| An. marshalli | 228 (9.1) | 68 (13) | 525 (31.3) | 821 (17.4) |

| An. garnhami | 7 (0.28) | 9 (1.7) | 45 (2.7) | 61 (1.3) |

| An. funestus group | 2 (0.08) | 1 (0.2) | 23 (1.3) | 26 (0.6) |

| An. pharoensis | 21 (0.84) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 21 (0.4) |

| Other anophelines† | 18 (0.7) | 9 (1.7) | 28 (1.7) | 55 (1.2) |

| Total | 2,506 (53) | 524 (11) | 1,678 (36) | 4,708 |

CDC = Centers for Disease Control; PSC = pyrethrum spray catch.

Others anophelines include An. tenebrosus, An. rhodensiensis, An. flavicosta, An. longipalpis, An. daniculicus, An. pretoriensis, An. chrysti, An. moucheti, An. distinctus, and An. zeimanni.

Monthly density of indoor-biting and indoor- and outdoor-resting mosquitoes.

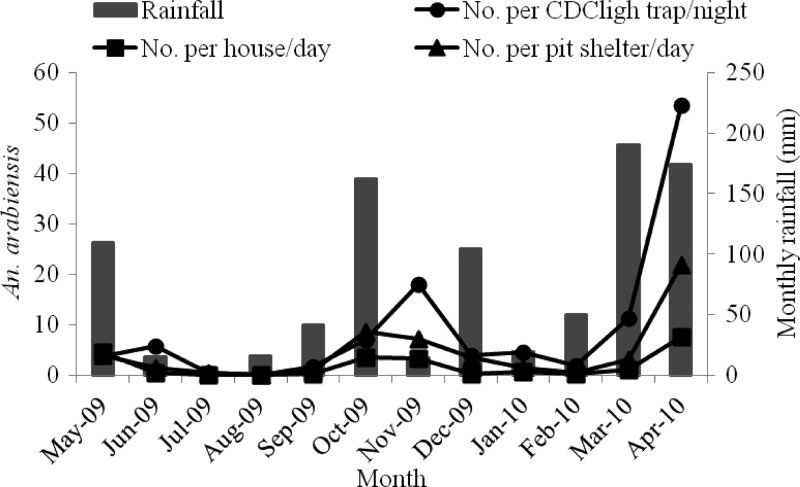

The monthly indoor and outdoor density of An. arabiensis in relation to rainfall is shown in Figure 2. Monthly density of indoor host-seeking An. arabiensis varied significantly (degrees of freedom [df] = 11, F = 6.0, P < 0.002). Collections peaked in April 2010 with 53.4/CDC light trap/night. In August 2009, no mosquitoes were found because of extremely low rainfall in June and July 2009. However, over most of the wet months (October, November, March, and April) the variation was not significant (P > 0.05, by HSD test).

Figure 2.

Monthly density of Anopheles arabiensis collected by three methods in Chano, southwestern Ethiopia. CDC = Centers for Disease Control.

The density of indoor-resting An. arabiensis also varied significantly (df =11, F = 5.5, P = 0.003) with a maximum of 7.6/house/day in April 2010. Seasonal trends were also reflected for outdoor-resting density of An. arabiensis (df =11, F = 8.1, P < 0.001), which had a maximum of 22/pit shelter/day and a minimum of 0/pit shelter/day.

The density of An. arabiensis was significantly associated with a one-month lag of rainfall in collections from CDC light traps (r = 0.81, P < 0.001), PSCs (r = 0.79, P = 0.002), and pit shelters (r = 0.63, P = 0.03). However, this association was not significant when An. arabiensis density was measured against rainfall in the month of collection or against a two-month lag.

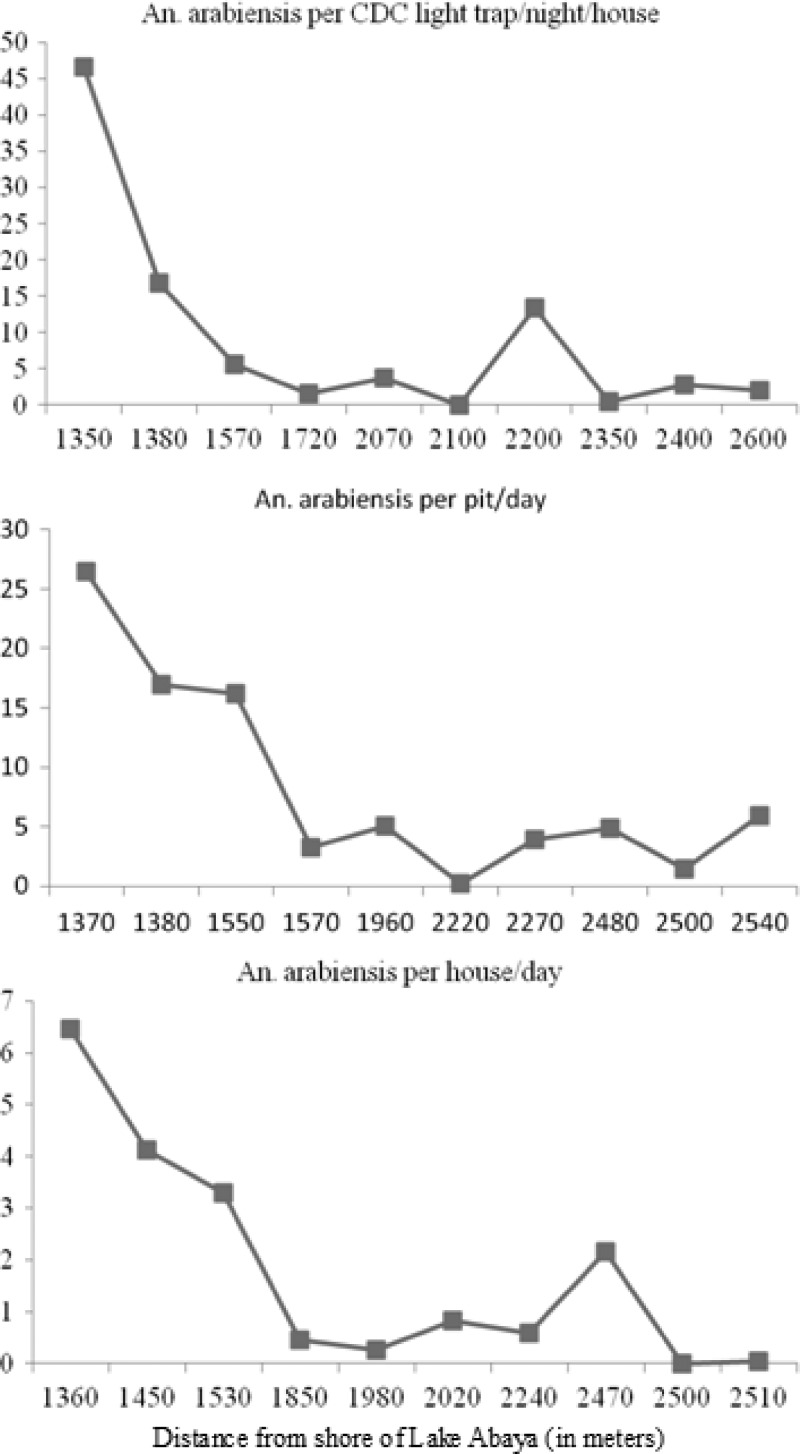

Household variations in indoor-biting and resting mosquitoes.

The association between densities of An. arabiensis and distance from the major breeding sites is shown in Figure 3. Mosquitoes were more abundant in houses located near main breeding sites on the shore of Lake Abaya than in those further away. Density of indoor-biting An. arabiensis differed significantly between houses (df = 9, F = 16.3, P < 0.001). Of 2,230 An. arabiensis sampled by CDC light traps, 74.3% (1,657) were from the 30% of houses that were closest to larval breeding sites. The distance of the houses closest to the breeding sites was 1350–1570 meters, and the density of indoor-biting An. arabiensis in these houses varied from 5.6/CDC light trap/house/night to 46.4/CDC light trap/house/night. In contrast, for houses further from the shore of the lake (2,350–2,600 meters), the density ranged from 0.4/CDC light trap/house/night to 2.8/CDC light trap/night.

Figure 3.

Relationship between distance from the identified major breeding site and household Anopheles arabiensis density in Chano, southwestern Ethiopia. CDC = Centers for Disease Control.

For PSCs, a similar trend in variation of indoor-resting density of An. arabiensis (df = 9, F = 8.5, P < 0.001) was observed. The density of An. arabiensis ranged between 3.3/house/day and 6.5/house/day in those houses closest to the breeding sites (1,360–1,530 meters) but ranged between 0.0 and 2.2/house/day in those houses further from the shore of the lake (1,980–2,510 meters). No significant variation was observed among houses between 1,360 and 1,530 meters from the shore of the lake (P = 0.83, by HSD test). The density of An. arabiensis in pit shelters also varied (df = 9, F = 9.0, P < 0.001).

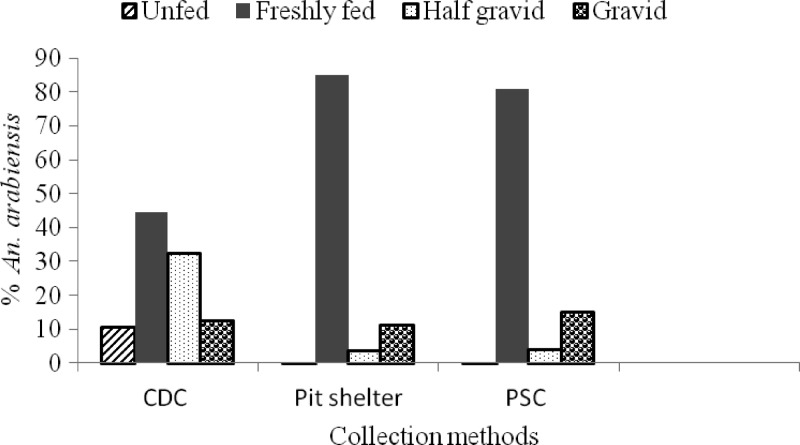

Abdominal conditions and parity rates.

Abdominal conditions of An. arabiensis from different collection sites are shown in Figure 4. Freshly fed An. arabiensis were dominant (60.3% of 3,724) followed gravid and half- gravid (33.2%), and the percentage of unfed was low (6.4%). The ratio of freshly fed An. arabiensis was higher in the PSCs (81% of 437) and pit shelters (85.1% of 1,057) than in CDC light traps (44.5% of 2,230). The proportion of gravid (including half-gravid) to freshly fed An. arabiensis was 1.35 times higher in PSCs than in pit shelters.

Figure 4.

Abdominal conditions of Anopheles arabiensis from different collection sites in Chano, southwestern Ethiopia. CDC = Centers for Disease Control; PSC = pyrethrum spray catch.

Unfed An. arabiensis were collected almost exclusively in CDC light traps (98.3% of 239). Of the small number of unfed An. arabiensis caught and dissected (n = 239) for ovarian ageing, the parous rate was 26.4% (63 of 239). Sixty-two percent (149 of 239) of unfed and 68% (43 of 63) of parous An. arabiensis were collected from the house nearest to the shore of the lake.

Sporozoite rates.

Overall, 4,534 Anopheles were analyzed for CSPs comprising An. arabiensis (n = 3,678), An. marshalli (n = 763), An. garnhami (n = 45), An. funestus group (n = 26), An. pharoensis (n = 15), and An. tenebrosus (n = 7). Of these mosquitoes, 14 An. arabiensis were positive for Plasmodium CSPs, 11 were positive for P. falciparum (78.6%), and 3 were positive for P. vivax 210 (21.4%). None of the tested An. arabiensis was positive for P. vivax 247 CSP, and no other anophelines were found to be positive for CSPs.

Monthly sporozoite rates of An. arabiensis from different collection sites are shown in Table 2. The greater numbers of (93% of 14) Plasmodium-positive An. arabiensis were collected during the wet months (October and November 2009 and March and April 2010). Seven of 11 P. falciparum sporozoite-positive An. arabiensis were captured by CDC light traps, three were collected in artificial pit shelters (3 of 11), and 1 by PSCs (1 of 11), although there was no statistically significant difference between the collection methods. The number of P. vivax-positive An. arabiensis was similar from all collection sites. The overall Plasmodium infection rate (P. falciparum and P. vivax) of An. arabiensis was 0.38%, and the P. falciparum sporozoite rate was 0.32% for CDC light traps, 0.28% for pit shelters, and 0.23% for PSCs. When categorized by species, the overall rate was 0.3% for P. falciparum and 0.08% for P. vivax 210.

Table 2.

Monthly circumsporozoite protein–positive Anopheles arabiensis collected by three methods from Chano in southwestern Ethiopia*

| Month and year | CDC light trap | PSC | Pit shelter | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. tested | Pf positive (%, 95% CI) | Pv positive (%, 95% CI) | No. tested | Pf positive (%, 95% CI) | Pv positive (%, 95% CI) | No. tested | Pf positive (%, 95% CI) | Pv positive (%, 95% CI) | |

| May 2009 | 73 | 0 | 0 | 90 | 0 | 0 | 75 | 0 | 0 |

| Jun 2009 | 105 | 1 (0.95) | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 32 | 0 | 0 |

| Jul 2009 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| Aug 2009 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sep 2009 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 0 |

| Oct 2009 | 131 | 0 | 1 (0.76) | 69 | 0 | 0 | 170 | 0 | 0 |

| Nov 2009 | 356 | 1 (0.28) | 0 | 67 | 1 (1.5) | 1 (1.5) | 144 | 2 (1.4) | 0 |

| Dec 2009 | 76 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 70 | 0 | 0 |

| Jan 2010 | 87 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 31 | 0 | 0 |

| Feb 2010 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| Mar 2010 | 224 | 1(0.44) | 0 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 62 | 1 (1.6) | 0 |

| Apr 2010 | 1,063 | 4 (0.38) | 0 | 150 | 0 | 0 | 435 | 0 | 1 (0.23) |

| Total | 2,184 | 7 (0.32, 0.13–0.66) | 1 (0.046, 0.001–0.26) | 436 | 1 (0.23, 0.006–1.27) | 1 (0.23, 0.006–1.27) | 1056 | 3 (0.28, 0.06–0.83) | 1 (0.09, 0.003–0.53) |

CDC = Centers for Disease Control; PSC = pyrethrum spray catches; Pf = Plasmodium falciparum; CI = confidence interval; Pv = P. vivax.

Entomologic inoculation rates.

The monthly EIRs of An. arabiensis estimated from CDC light traps and PSCs are shown in Table 3. The monthly EIRs of An. arabiensis were highest in the wet months. A one-month lag of rainfall was significantly associated with the monthly EIR (r = 0.74, P = 0.006) of An. arabiensis from CDC light traps, but there was no significant association with the month of collection or with a two-month lag of rainfall (P > 0.05).

Table 3.

Monthly EIR of Anopheles arabiensis from CDC light traps and pyrethrum spray catches in Chano, southwestern Ethiopia*

| Month and year | CDC | PSC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. collected | No. tested for CSP | EIR† | EIR‡ (95% CI) | No. collected | No. tested for CSP | Pf EIR | Pv EIR | |

| May 2009 | 76 | 73 | 0 | 0 | 91 | 90 | 0 | 0 |

| June 2009 | 114 | 105 | 2.6 | 2.4 (0.06–12.0) | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| July 2009 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| August 2009 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| September 2009 | 33 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| October 2009 | 140 | 131 | 2.5§ | 2.4§ (0.06–11.9) | 69 | 69 | 0 | 0 |

| November 2009 | 361 | 356 | 2.4 | 2.4 (0.06–12.0) | 67 | 67 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| December 2009 | 77 | 76 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| January 2010 | 90 | 87 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 14 | 0 | 0 |

| February 2010 | 36 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| March 2010 | 226 | 224 | 2.5 | 2.5 (0.06–12.4) | 24 | 24 | 0 | 0 |

| April 2010 | 1,069 | 1,063 | 9.7 | 9.6 (2.7–21.2) | 151 | 150 | 0 | 0 |

EIR = entomologic inoculation rate; CDC = Centers for Disease Control; PSC = pyrethrum spray catch; CSP = circumsporozoite protein; CI = confidence interval; Pf = Plasmodium falciparum; Pv = P. vivax.

Standard method: 1.605 (no. enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA] positive from CDC light trap/no. ELISA tested) × (no. An. arabiensis collected from CDC light trap/no. of catches) × no. days per month.

Alternative method: 1.605 (no. ELISA positive/no. catches) × no. days per month.

P. vivax EIR.

The estimated annual EIRs of Anopheles from CDC light traps and PSCs are shown in Table 4. Based on the alternative method, the estimated annual P. falciparum EIR of An. arabiensis from CDC light traps was 17.1 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 7.0–34.6 ib/p/year, whereas that of P. vivax was 2.4 (95% CI = 0.06–13.4). The EIR from PSCs was 0.1 ib/p/year for P. falciparum and P. vivax.

Table 4.

Annual EIR of Anopheles arabiensis from CDC light traps and PSCs in Chano, southwestern Ethiopia*

| Variable | CDC light trap | PSC | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. collected | No. positive/no. tested (%) | EIR† | EIR‡ (95% CI) | No. collected | No. positive/no. tested (%) | EIR | |

| Pf EIR | 2,230 | 7/2,184 (0.32) | 17.4 | 17.1 (7.0–34.6) | 437 | 1/436 (0.23) | 0.1 |

| Pv EIR | 2,230 | 1/2,184 (0.046) | 2.5 | 2.4 (0.06–13.4) | 437 | 1/436 (0.23) | 0.1 |

EIR = entomologic inoculation rate; CDC = Centers for Disease Control; PSCs = pyrethrum spray catches; CI = confidence interval; Pf = Plasmodium falciparum; Pv = P. vivax.

Standard method: 1.605 (no. enzyme-linked immunsorbent assay [ELISA] positive from CDC light trap/no. ELISA tested) × (no. of Anopheles arabiensis collected from CDC light trap/no. catches) × 365,

Alternative method: 1.605 (no. ELISA positive/no. catches) × 365.

Estimates of the EIRs of An. arabiensis were also made individually for the three sub-villages, and for the wet (including main and small rainy months) and dry seasons for CDC light traps (Table 5). The P. falciparum EIR was 2.4 (95% CI = 0.12–11.7) in the dry season and 14.7 (95% CI = 5.9–29.4) in the wet season. This finding represented 6.1-fold more infectious bites in the wet than in the dry season. In sub-village 03, P. falciparum EIR was 24.4 ib/p/year (95% CI = 6.7–60.3) and P. vivax EIR was 5.8 ib/p/year (95% CI = 0.3–29.3). The annual P. falciparum EIR of An. arabiensis from CDC light traps varied between houses from 0 ib/p/year (in 60% of houses) to 73.2 (95% CI = 15.6–187) ib/p/year in house nearest to the major breeding site.

Table 5.

Estimated EIR of Anopheles arabiensis from CDC light traps from Chano, southwestern Ethiopia, by sub-village and season*

| Variable | No. collected | No. tested | No. catches | No. positive (%) | Pf EIR† | Pf EIR‡ (95% CI) | No. positive (%) | Pv EIR† | Pv EIR‡ (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-village | 01 | 124 | 117 | 72 | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0.0 (0.0–24.0) | 0 | 0 | 0.0 (0–24.0) |

| 02 | 411 | 409 | 72 | 3 (0.73) | 24.5 | 24.4 (5.1–68.5) | 0 | 0 | 0.0 (0–24.0) | |

| 03 | 1,695 | 1,658 | 96 | 4 (0.24) | 25.0 | 24.4 (6.7–60.3) | 1 (0.06) | 6.2 | 5.8 (0.3–29.3) | |

| Season | Wet§ | 1,949 | 1,923 | 120 | 6 (0.31) | 14.9 | 14.7 (5.9–29.4) | 1 (0.05) | 2.5 | 2.4 (0.12–11.7) |

| Dry¶ | 281 | 261 | 120 | 1 (0.38) | 2.6 | 2.4 (0.12–11.7) | 0 | 0 | 0.0 (0–14.6) | |

EIR = entomologic inoculation rate; CDC = Centers for Disease Control; Pf = Plasmodium falciparum; CI = confidence interval; Pv = P. vivax.

Standard method: 1.605 (No. enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA] positive from CDC light trap/no. ELISA tested) × (no. of Anopheles arabiensis collected from CDC light trap/no. catches) × 365.

Alternative method: 1.605 (no. positive ELISA/no. catches) × 365.

EIR calculated by multiplying by 182 days.

EIR calculated by multiplying by 183 days.

From the PSCs, two of the An. arabiensis collected on the same day from the house nearest the breeding site (with the maximum biting density of mosquitoes) were positive for CSP (1 for P. falciparum and 1 for P. vivax). The mean biting rate of An. arabiensis was 0.33 b/p/n, and the estimated EIR was 0.1 ib/p/year, which was calculated by multiplying the mean human-biting density by HBI (from a previous report18) and the CSP rate.

Discussion

This study showed that the estimated annual P. falciparum EIR of An. arabiensis in Chano, Ethiopia was 17.1 infectious bites/person/year. Anopheles arabiensis was identified as the principal vector of Plasmodium in the area, and the risk of exposure to infectious bites was higher in wet seasons than in dry seasons. There was a high variation in EIRs between houses, and a maximum in the house closest to larval-breeding sites.

The estimated EIR from CDC light traps was higher and relatively more representative than that of PSCs because a greater number of Plasmodium-positive An. arabiensis were collected in CDC light traps. We concluded that the EIR from PSCs cannot be representative of the study area because the two CSP-positive specimens were sampled from one house on the same day. The PSCs also had lower relative sampling efficiency for Anopheles mosquitoes than CDC light traps. The most likely explanation is that indoor-resting adults might leave houses immediately after feeding,7 before spraying, and during spraying.15 Therefore, using PSCs for estimating EIR can underestimate the human-biting rates.15 In Senegal, lower EIR was reported for PSCs compared with CDC light traps and HLC for An. gambiae,27 and CDC traps were more efficient than PSCs in collecting more species.27 Moreover, estimates of human-biting rates of An. arabiensis from the CDC light trap were comparable with HLC in an area with low mosquito density and high insecticide-treated mosquito net use.28 However, CDC light traps failed to determine the human-biting rate of An. gambiae s.s. on Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea.29 In Tanzania, approximately two-thirds of the human-biting An. gambiae complex were collected in a CDC light trap compared with the number caught by HLC.13

The HLC is a direct approach for estimating the human-biting rate12 and is effective in collecting mosquitoes with high sporozoite rates.27 However, this method could not be applied in our study because it is considered unethical in Ethiopia. It is known that the efficiency of CDC light traps or HLC can vary according to mosquito species.29 Despite various limitations of CDC light traps as a proxy for HLC, we believe that the EIR values from CDC light traps represented a reasonable estimate of the infective bites of An. arabiensis for our study area. However, the use of different methods for estimating EIR makes comparison of EIRs difficult between regions and between countries.4

The data from the P. falciparum sporozoite rate determination strongly suggest that An. arabiensis was the principal vector of malaria in the study area, as reported.2,14 We identified 16 species of anophelines, of which 5 had been reported from southern Ethiopia.14 Unlike most studies in this country,2,14,30 An. pharoensis were rarely sampled in our study site. Anopheles marshalli was the second most abundant species although in a previous study from Sille in southern Ethiopia, it was found only at low densities.14 The high proportion of HBI18 and the moderately frequent occurrence of An. marshalli indoors suggests a need for further investigations into its potential role as a vector of malaria in this area and other areas in Ethiopia.

The parous rate of An. arabiensis in our study was lower than the 73.2% reported in Sille in 200614 and the 58.3% reported in Awash Valley in 1996.31 This difference could be the result of mass emergence of nulliparous adults from the nearest breeding sites32 because most unfed An. arabiensis were collected from a house near the shore of the lake. The proportion of gravid (including half-gravid) to freshly fed An. arabiensis was 1.35 times higher for PSCs than for pit shelters, which suggested a tendency for endophilic rather than exophilic behavior. Exophilic and endophilic behavior of An. arabiensis has been reported in southern Ethiopia.18,33

We observed a clustered distribution of Plasmodium CSPs-positive An. arabiensis in a sub-village near the shore of the lake. This finding is consistent with recently reported clustering of malaria cases from the same part of a village34 and the distribution of malaria vectors in Sille in southern Ethiopia.35 The P. falciparum sporozoite rate of An. arabiensis from CDC light traps (0.32%) is comparable with that reported from Sille (0.5%) for HLCs,14 but the overall sporozoite rate (0.38%) was lower than the 2.26% rate in Sille.14 A higher P. falciparum CSP rate of An. arabiensis from CDC light traps was also reported from Ziway in the Central Rift Valley of Ethiopia (1.18%).36 Krafsur15 in 1977 reported a higher sporozoite rate (1.87%) for indoor-resting An. arabiensis, and a report in 2013 for south-central Ethiopia16 showed a P. falciparum CSP rate of 0.3% for CDC light traps and 0.2% for PSCs for An. arabiensis.

This study showed that 93% of sporozoite-positive An. arabiensis were found in the wet season and together with EIR were closely associated with rainfall, as has been demonstrated in Gambela in western Ethiopia,15 in Ifakara, Tanzania,24 in Eritrea37 and elsewhere in Africa.3,9 It is clear that the risk of malaria transmission increases during periods of higher EIR9,38 and a decrease in density and number of sporozoite-positive mosquitoes results in a decreased EIR.4 Based on CDC light traps, the estimated annual P. falciparum EIR (17.1 ib/p/year) of An. arabiensis was higher compared with EIRs of An. arabiensis in Gambela (5.36 ib/p/year) and nearby villages (10.47 ib/p/year) estimated from PSCs15 but much lower than the overall EIR from river villages in Gambela (96.67ib/p/year). Recently, an annual P. falciparum EIR of 3.66 ib/p/year for An. arabiensis was reported from the central highland of southern Ethiopia.16 However, in two other studies in neighboring countries, higher EIRs than those recorded in our study have been reported. One study that lasted more than two years and used HLCs37 reported EIRs of 70.6 ib/p/year from Hiletsidi in the Gash Barka zone and 32.1 ib/p/year in Maiaini in the Debub zone in Eritrea, and another study using the PSC method estimated an annual EIR for An. arabiensis of 55.48 ib/p/year in eastern Sudan.39

The EIR has implications for monitoring the suitability of vector control interventions.4,8 Current malaria vector interventions such as LLINs and IRS reduce EIR in many malaria-endemic countries, but none of these interventions has managed to reduce EIR to < 1 ib/p/year,4 except in the Garki Project (which used propoxur for IRS) and reduced EIR only temporarily.40 It has been suggested that the annual EIR should be < 1 ib/p/year to reduce and interrupt malaria transmission, based on the finding of a linear relationship between malaria prevalence and EIRs.41 Our EIR estimate (17.1 ib/p/year) is more than sufficient to continue malaria transmission in the area, where incidence is reported to be 3.6/10,000 person-weeks of observation.17

Finally, this study clearly identified An. arabiensis as the principal vector of malaria in the Chano area, and the estimated EIR from CDC light traps was higher and more representative than that of PSCs. The risk of exposure to infectious bites was higher in the houses closer to the larval breeding sites, and in wet seasons than in dry seasons. Besides advocating about using the malaria vector control programs for the general population, we advise the vector control programs to focus those households with malaria clustering (hot spots). Such interventions could include IRS during the seasons of the local malaria vector density. Currently, we study if combining screening doors and windows with IRS and LLINs for those houses closer to the breeding sites will reduce malaria transmission. Because the nearby lake was the main mosquito breeding site, it might be worthwhile to assess if aerial spraying of larvicide on the lakeshore would reduce malaria in such populations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Arba Minch University for providing transport for fieldwork, Yohannes Negash (Aklilu Lemma Institute of Pathobiology) for providing technical support during mosquito analysis; Tegagn Kanko and Seifu Belete for providing support during collecting of mosquitoes, and the residents of Chano for cooperation and for allowing us to collect mosquitoes. Fekadu Massebo designed the study; conducted field and laboratory work, performed data analysis and interpretation, and wrote the manuscript; Meshesha Balkew designed the study, supervised field and laboratory work, and wrote the manuscript; Teshome Gebre-Michael designed the study, supervised laboratory work, and revised the manuscript; and Bernt Lindtjørn designed the study, supervised field work, provided statistical input, and revised the manuscript.

Footnotes

Financial support: This study was supported by the Centre for International Health, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway.

Authors' addresses: Fekadu Massebo, Department of Biology, Arba Minch University, Arba Minch, Ethiopia, and Centre for International Health, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway, E-mail: fekimesi@yahoo.com. Meshesha Balkew and Teshome Gebre-Michael, Aklilu Lemma Institute of Pathobiology, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, E-mails: meshesha_b@yahoo.com and teshomegm@gmail.com. Bernt Lindtjørn, Centre for International Health, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway, E-mail: bernt.lindtjorn@cih.uib.no.

References

- 1.Otten M, Aregawi M, Were W, Karema C, Medin A, Bekele W, Jima D, Gausi K, Komatsu R, Korenromp E, Low-Beer D, Grabowsky M. Initial evidence of reduction of malaria cases and deaths in Rwanda and Ethiopia due to rapid scale-up of malaria prevention and treatment. Malar J. 2009;8:14. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abose T, Yeebiyo Y, Olana D, Alamirew D, Beyene Y, Regassa L, Mengesha A. Re-orientation and Definition of the Role of Malaria Vector Control in Ethiopia. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelly-Hope L, McKenzie FE. The multiplicity of malaria transmission: a review of entomological inoculation rate measurements and methods across sub-Saharan Africa. Malar J. 2009;8:19. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaukat A, Breman JG, McKenzie FE. Using entomological inoculation rate to assess the impact of vector control on malaria parasite transmission and elimination. Malar J. 2010;9:122. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coluzzi M. Heterogeneities of the malaria vectorial system in tropical Africa and their significance in malaria epidemiology and control. Bull World Health Organ. 1984;62:107–113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Day J. Host-seeking strategies of mosquito diseases vectors. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2005;21:17–22. doi: 10.2987/8756-971X(2005)21[17:HSOMDV]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garrett-Jones C, Boreham PF, Pant CP. Feeding habits of anophelines (Diptera: Culicidae) in 1971–1978, with reference to the human blood index: a review. Bull Entomol Res. 1980;70:165–185. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ulrich J, Naranjo DP, Alimi TO, Müller GC, Beier JC. How much vector control is needed to achieve malaria elimination? Trends Parasitol. 2013;29:104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hay S, Rogers DJ, Toomer JF, Snow RW. Annual Plasmodium falciparum entomological inoculation rates (EIR) across Africa: literature survey, internet access and review. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000;94:113–127. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(00)90246-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Omumbo J, Guerrab CA, Hay SI, Snow RW. The influence of urbanisation on measures of Plasmodium falciparum infection prevalence in east Africa. Acta Trop. 2005;93:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trape J, Rogier C. Combating malaria morbidity and mortality by reducing transmission. Parasitol Today. 1996;12:236–240. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(96)10015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization . Manual on Practical Entomology in Malaria. Part 2: Methods and Techniques. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lines J, Curtis CF, Wilkes TJ, Njunwa T. Monitoring human biting mosquitoes in Tanzania with light traps hung beside mosquito nets. Bull Entomol Res. 1991;81:77–84. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taye A, Hadis M, Adugna N, Tilahun D, Wirtz RA. Biting behaviour and Plasmodium infection rates of Anopheles arabiensis from Sille, Ethiopia. Acta Trop. 2006;97:50–54. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krafsur E. The bionomics and relative prevalence of Anopheles species with respect to the transmission of Plasmodium to man in western Ethiopia. J Med Entomol. 1977;25:180–194. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/14.2.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Animut A, Gebre-Michael T, Balkew M, Lindtjørn B. Blood meal sources and entomological inoculation rates of anophelines along a highland altitudinal transect in south-central Ethiopia. Malar J. 2013;12:76. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loha E, Lindtjorn B. Predictors of Plasmodium falciparum malaria incidence in Chano Mille, south Ethiopia: a longitudinal study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87:450–459. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Massebo F, Balkew M, Gebre-Michael T, Lindtjørn B. Blood meal origins and insecticide susceptibility of Anopheles arabiensis from Chano in south-west Ethiopia. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:44. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Viste E, Korecha D, Sorteberg A. Recent drought and precipitation tendencies in Ethiopia. Theor Appl Climatol. 2013;112:535–551. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silver J. Mosquito Ecology: Field Sampling Methods. New York: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gillies M, Coetzee M. A supplement to the anopheline of Africa south of the Sahara. S Afr Inst Med Res. 1987;55:143. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Detinova T. Age Grouping Methods in Diptera of Medical Importance, with Special Reference to Some Vectors of Malaria. Geneva: World Health Organization, Monograph Series, No. 47; 1962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beier J, Perkins PV, Wirtz RA, Whitmire RE, Mugambi M, Hockmeyer WT. Field evaluation of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for Plasmodium falciparum sporozoite detection in anopheline mosquitoes from Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1987;36:459–468. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1987.36.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drakeley C, Schellenberg D, Kihondaj J, Sousa CA, Arez AP, Lopes D, Lines J, Mshinda IH, Lengelers C, Schellenberg AJ, Tanner M, Alonso P. An estimation of the entomological inoculation rate for Ifakara: a semi-urban area in a region of intense malaria transmission. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8:767–774. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization . Malaria Entomology and Vector Control. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garrett-Jones C. The human blood index of malaria vectors in relation to epidemiological assessment. Bull World Health Organ. 1964;30:241–261. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ndiath M, Mazenot C, Gaye A, Konate L, Bouganali C, Faye O, Sokhna C, Trape JF. Methods to collect Anopheles mosquitoes and evaluate malaria transmission: a comparative study in two villages in Senegal. Malar J. 2011;10:270. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fornadel C, Norris LC, Norris DE. Centers for disease control light traps for monitoring Anopheles arabiensis human biting rates in an area with low vector density and high insecticide-treated bed net use. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83:838–842. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Overgaard H, Sæbø S, Reddy MR, Reddy VP, Abaga S, Matias A, Slotman MA. Light traps fail to estimate reliable malaria mosquito biting rates on Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea. Malar J. 2012;11:56. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nigatu W, Petros B, Lulu M, Adugna N, Wirtz R. Species composition, feeding and resting behaviour of the common anthropophilic anopheline mosquitoes in relation to malaria transmission in Gambella, south-west Ethiopia. Int J Trop Insect Sci. 1994;15:371–377. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ameneshewa B, Service MW. The relationship between female body size and survival rate of the malaria vector Anopheles arabiensis in Ethiopia. Med Vet Entomol. 1996;10:170–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.1996.tb00724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Charlwood J, Smith T, Kihonda J, Heiz B, Billingsley PF, Takken W. Density independent feeding success of malaria vectors (Diptera: Culicidae) in Tanzania. Bull Entomol Res. 1995;85:29–35. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tirados IC, Gibson G, Torr SJ. Blood feeding behaviour of the malaria mosquito Anopheles arabiensis: implications for vector control. Med Vet Entomol. 2006;20:425–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2006.652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loha E, Lunde TM, Lindtjørn B. Effect of bednets and indoor residual spraying on spatio-temporal clustering of malaria in a village in south Ethiopia: a longitudinal study. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e47354. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ribeiro J, Seulu F, Abose T, Kidane G, Teklehaimanot A. Temporal and spatial distribution of anopheline mosquitoes in an Ethiopian villages: implications for malaria control strategies. Bull World Health Organ. 1996;74:299–305. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kibret S, Alemu Y, Boelee E, Tekie H, Alemu D, Petros B. The impact of a small-scale irrigation scheme on malaria transmission in Ziway area, central Ethiopia. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15:41–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shililu J, Ghebremeskel T, Mengistu S, Fekadu H, Zerom M, Mbogo C, Githure J, Novak R, Brantly E, Beier JC. High seasonal variation in entomologic inoculation rates in Eritrea, a semi-arid region of unstable malaria in Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;69:607–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith D, Dushoff J, Snow RW, Hay SI. The entomological inoculation rate and Plasmodium falciparum infection in African children. Nature. 2005;438:492–495. doi: 10.1038/nature04024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Himeidan Y, Elzaki MM, Kweka EJ, Ibrahim M, Elhassan IM. Pattern of malaria transmission along the Rahad River basin, eastern Sudan. Parasit Vectors. 2011;4:109. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Molineaux L, Gramiccia G. The Garki Project: Research on the Epidemiology and Control of Malaria in the Sudan Savanna of West Africa. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beier J, Killeen GF, Githure JI. Short report: entomologic inoculation rates and Plasmodium falciparum malaria prevalence in Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61:109–113. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]