Abstract

Zika virus infection closely resembles dengue fever. It is possible that many cases are misdiagnosed or missed. We report a case of Zika virus infection in an Australian traveler who returned from Indonesia with fever and rash. Further case identification is required to determine the evolving epidemiology of this disease.

A previously healthy 52-year-old Australian woman had malaise and rash after a 9-day holiday to Jakarta, Indonesia. On arrival in Australia, she initially reported some fatigue and non-specific malaise, followed by a prominent headache. The headache subsequently began to subside, but on day 4 of her symptoms, a maculopapular rash developed that started on her trunk before spreading to her back and limbs, but not her face. This rash was accompanied by generalized myalgia, some loose bowel movements, and an occasional dry cough. She did not experience any significant sweats or rigors.

Examination on day 5 of her illness showed mild bilateral conjunctivitis and a diffuse maculopapular rash, but no evidence of lymphadenopathy or tenosynovitis. Investigations at this time showed a total leukocyte count of 3.6 × 109 cells /L (reference range = 4.0–11.0 × 109 cells/L), a hemoglobin level of 137 g/L (reference range = 115–150 g/L), a hematocrit of 39%, and platelet count of 230 × 109 cells/L (reference range = 140–400 × 109 cells/L). Reactive lymphocytes were present on a blood film. Baseline liver and renal function test results were normal.

Dengue serologic analysis on day 5 of her illness showed a positive result for IgG, a weakly positive result for IgM, but a negative result for nonstructural protein 1 (NS1 antigen) by enzyme immunoassay. A generic flavivirus group polymerase chain reaction (PCR) result was positive, and the patient was provisionally given a diagnosis of dengue fever. A dengue-specific PCR result was negative. However, sequencing of the original flavivirus PCR product identified it as Zika virus (GenBank accession no. KF258813). The patient's symptoms had completely resolved after two weeks from onset of symptoms, and a convalescent PCR result at this time was negative for flavivirus.

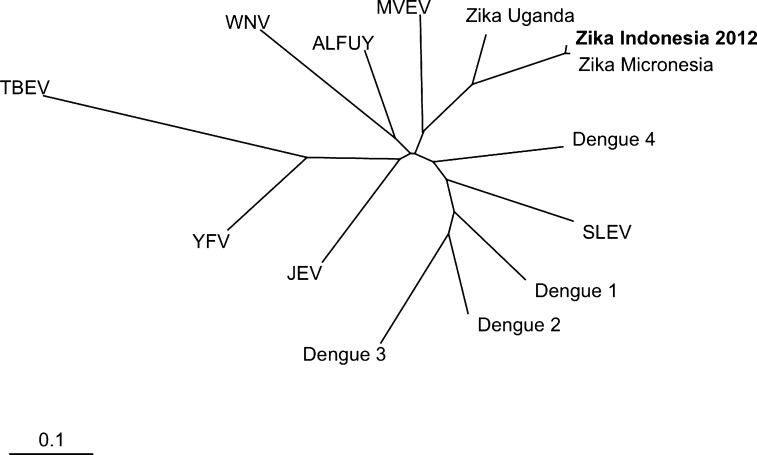

Zika virus is an RNA-containing flavivirus first isolated in 1948 from a sentinel rhesus monkey in the Zika Forest of Uganda.1 A number of cases of infection with this virus have since been reported in Africa, India, Southeast Asia, and Micronesia. Recent phylogenetic analysis of reported Zika virus strains has suggested that strains from Africa and Asia have emerged as two distinct virus lineages (Figure 1).2

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree showing relationships of Zika virus to other flaviviruses. Bold indicates virus isolated in this study. Scale bar indicates nucleotide substitutions per site. WNV = West Nile virus; ALFUV = subtype of MVEV; MVEV = Murray Valley encephalitis virus; SLEV = St. Louis encephalitis virus; JEV = Japanese encephalitis virus; YFV = yellow fever virus; TBEV = tick-borne encephalitis virus.

Infection with Zika virus results in a clinical syndrome similar to illness resulting from infection with other flaviviruses. Commonly reported symptoms include malaise, headache, maculopapular rash, myalgia, arthralgia, conjunctivitis, and fever.1,3 Diagnosis can be confirmed by demonstration of specific antibodies against Zika virus in serum or by PCR detection of the virus.4–6 Detailed serologic testing of the Yap Islands Zika virus outbreak in 2007 showed limited cross-reactivity with IgM against other flaviviruses, including dengue virus.7

To our knowledge, this is the first case of Zika virus infection reported in a returned traveler to Australia, although serologic evidence of Zika virus infection has been reported in Java, Indonesia.8 The only other reported cases outside virus-endemic regions were in two U.S. scientists working in Senegal who showed development of clinical infection after returning to the United States, and one scientist subsequently infected his wife, possibly through sexual transmission.9 However, it is likely that many cases are either undiagnosed (because of mild symptoms) or misdiagnosed, presumably most commonly as dengue fever, given their clinical similarities. Cross-sectional surveys in Africa and Asia show higher seroprevalence of antibodies against Zika virus than is suggested on the basis of the reported incidence of Zika infection.2

For returned travelers, accurate diagnosis and rapid differentiation from other possible travel-related illnesses is important in minimizing healthcare-associated morbidity. In our patient, although a provisional diagnosis of dengue fever was made, the absence of thrombocytopenia and the negative results for nonstructural protein 1 in the context of a positive PCR result for flavivirus was believed to be unusual. To our knowledge, thrombocytopenia has not been reported with confirmed Zika virus infection.

Although severe cases of Zika virus infection in humans have not been described, the spectrum of clinical disease remains uncertain. As with other flaviviruses, a seemingly indolent virus may in some cases be associated with more significant illness. With more frequent identification of cases through pan-flavirvirus molecular testing, better characterization of the evolving epidemiology and full clinical spectrum of Zika virus infection will be possible.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Jason C. Kwong has received financial assistance from Pfizer to attend an international conference. Karin Leder has received funding from GlaxoSmithKline for a study on hepatitis B, and financial assistance from GlaxoSmithKline and Sanofi Pasteur to attend international conferences.

Authors' addresses: Jason C. Kwong and Karin Leder, Victorian Infectious Diseases Service, The Royal Melbourne Hospital, Parkville, Victoria, Australia, E-mails: kwongj@gmail.com and karin.leder@monash.edu. Julian D. Druce, Victorian Infectious Diseases Reference Laboratory, North Melbourne Victoria, Australia, E-mail: julian.druce@mh.org.au.

References

- 1.Heang V, Yasuda CY, Sovann L, Haddow AD, Travassos da Rosa AP, Tesh RB, Kasper MR. Zika virus infection, Cambodia, 2010. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:349–351. doi: 10.3201/eid1802.111224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haddow AD, Schuh AJ, Yasuda CY, Kasper MR, Heang V, Huy R, Guzman H, Tesh RB, Weaver SC. Genetic characterization of Zika virus strains: geographic expansion of the Asian lineage. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1477. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duffy MR, Chen TH, Hancock WT, Powers AM, Kool JL, Lanciotti RS, Pretrick M, Marfel M, Holzbauer S, Dubray C, Guillaumot L, Griggs A, Bel M, Lambert AJ, Laven J, Kosoy O, Panella A, Biggerstaff BJ, Fischer M, Hayes EB. Zika virus outbreak on Yap Island, Federated States of Micronesia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2536–2543. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayes EB. Zika virus outside Africa. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1347–1350. doi: 10.3201/eid1509.090442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faye O, Faye O, Dupressoir A, Weidmann M, Ndiaye M, Alpha Sall A. One-step RT-PCR for detection of Zika virus. J Clin Virol. 2008;43:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balm MN, Lee CK, Lee HK, Chiu L, Koay ES, Tang JW. A diagnostic polymerase chain reaction assay for Zika virus. J Med Virol. 2012;84:1501–1505. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lanciotti RS, Kosoy OL, Laven JJ, Velez JO, Lambert AJ, Johnson AJ, Stanfield SM, Duffy MR. Genetic and serologic properties of Zika virus associated with an epidemic, Yap State, Micronesia, 2007. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1232–1239. doi: 10.3201/eid1408.080287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olson JG, Ksiazek TG, Suhandiman, Triwibowo. Zika virus, a cause of fever in Central Java, Indonesia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1981;75:389–393. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(81)90100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foy BD, Kobylinski KC, Chilson Foy JL, Blitvich BJ, Travassos da Rosa A, Haddow AD, Lanciotti RS, Tesh RB. Probable non-vector-borne transmission of Zika virus, Colorado, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:880–882. doi: 10.3201/eid1705.101939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]