Poneh Adib-Samii

Poneh Adib-Samii, MBBS

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,*,

Natalia Rost

Natalia Rost, MD

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,*,

Matthew Traylor

Matthew Traylor, MSc

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,

William Devan

William Devan, BS

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,

Alessandro Biffi

Alessandro Biffi, MD

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,

Silvia Lanfranconi

Silvia Lanfranconi, MD

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,

Kaitlin Fitzpatrick

Kaitlin Fitzpatrick, BSc

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,

Steve Bevan

Steve Bevan, PhD

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,

Allison Kanakis

Allison Kanakis, BS

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,

Valerie Valant

Valerie Valant, BA

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,

Andreas Gschwendtner

Andreas Gschwendtner, MD

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,

Rainer Malik

Rainer Malik, PhD

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,

Alexa Richie

Alexa Richie, MPH

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,

Dale Gamble

Dale Gamble, MHSc

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,

Helen Segal

Helen Segal, PhD

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,

Eugenio A Parati

Eugenio A Parati, MD

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,

Emilio Ciusani

Emilio Ciusani, PhD

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,

Elizabeth G Holliday

Elizabeth G Holliday, PhD

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,

Jane Maguire

Jane Maguire, PhD

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,

Joanna Wardlaw

Joanna Wardlaw, MD

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,

Bradford Worrall

Bradford Worrall, MD

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,

Joshua Bis

Joshua Bis, PhD

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,

Kerri L Wiggins

Kerri L Wiggins, MA

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,

Will Longstreth

Will Longstreth, MD

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,

Steve J Kittner

Steve J Kittner, MD

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,

Yu-Ching Cheng

Yu-Ching Cheng, PhD

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,

Thomas Mosley

Thomas Mosley, PhD

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,

Guido J Falcone

Guido J Falcone, MD

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,

Karen L Furie

Karen L Furie, MD

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,

Carlos Leiva-Salinas

Carlos Leiva-Salinas, MD

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,

Benison C Lau

Benison C Lau, BS

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,

Muhammed Saleem Khan

Muhammed Saleem Khan, MSc

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1;

Australian Stroke Genetics Collaborative1,‡;

Wellcome Trust Case-Control Consortium-2 (WTCCC2)1,‡;

METASTROKE1,

Pankaj Sharma

Pankaj Sharma, PhD

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,

Myriam Fornage

Myriam Fornage, PhD

1Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK (P.A.-S., M.T., S.L., S.B., H.S.M.); Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (N.R., W.D., A.B., K.F., A.K., V.V., G.J.F., J.R.); Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA (N.R.); Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Klinikum der Universität München, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany (A.G., R.M., M.D.); Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL (A.R., D.G., J.M.); Stroke Prevention Research Unit, Nuffield Department of Neuroscience, University of Oxford, UK (H.S., P.M.R.); Department of Cerebrovascular Diseases (E.A.P., G.B.B.), and Laboratory of Clinical Pathology and Medical Genetics (E.C.), Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta,” Milano, Italy; Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Hunter Medical Research Institute and School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (E.G.H., C.L.); Priority Research Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health and Faculty of Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia (J.M.); Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Neuroimaging Sciences and Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK (J.W., C.L.); University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (B.W.); Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (J.B., K.L.W., W.L.); Department of Neurology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K., Y.-C.C.); Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (S.J.K.); University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS (T.M.); Department of Neurology, Brown University, Providence, RI (K.L.F.); Department of Radiology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (C.L.-S., B.C.L.); Imperial College Cerebrovascular Research Unit (ICCRU), Imperial College London, London, UK (M.S.K., P.S.); University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX (M.F.); Group Health Research Institute, Group Health, Seattle, WA (B.M.P.); and Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA (J.R.)

1,

Braxton D Mitchell

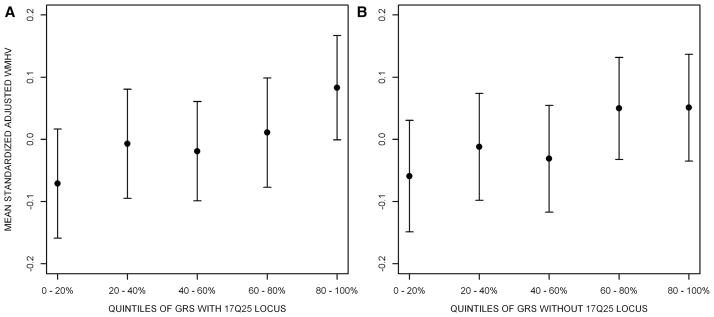

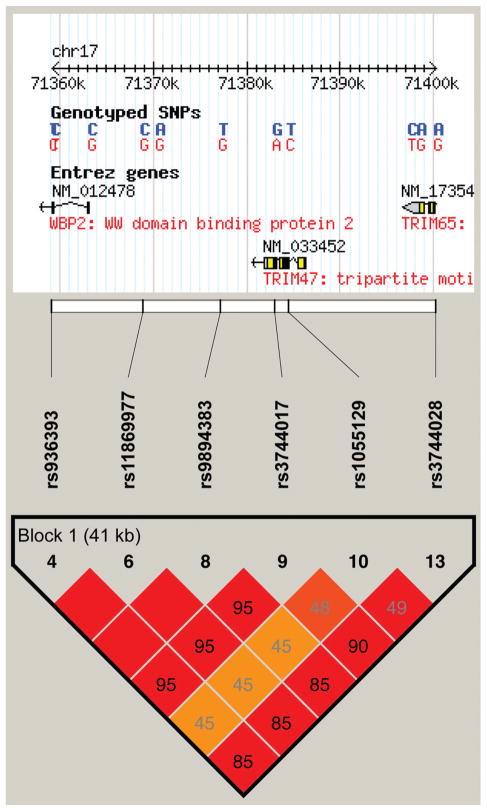

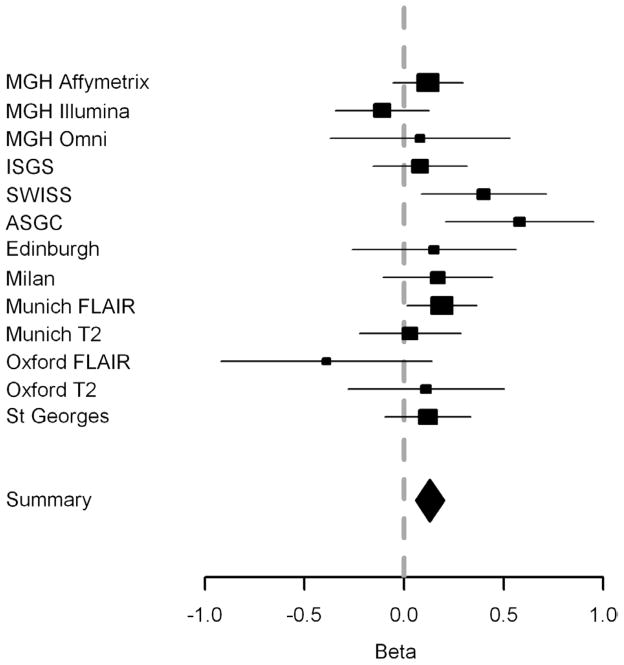

Braxton D Mitchell, PhD