Abstract

Plasma steady state methotrexate (MTX) level and red blood cell (RBC) MTX and folate concentrations were evaluated in 1124 children with newly diagnosed acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) enrolled on the Pediatric Oncology Group studies 9005 (lower risk; Regimens A and C) and 9006 (higher risk; Regimen A). These regimens included intermediate dose MTX (1 gram/m2) given as a 24 hour infusion every other week for 12 doses during intensification. Plasma MTX level was evaluated at the end of MTX infusions. RBC MTX and folate concentrations were measured at the end of intensification. The five year continuous complete remission (CCR) was 76 ± 1.4% versus 85 ± 3.0% for those patients with steady state MTX levels ≤ and > 14 µM, respectively (p=0.0125). Hispanic children had significantly reduced median steady state MTX levels, 8.7 µM, compared to non-Hispanic children, 9.95 µM (p=0.0015), but this did not correlate with a difference in outcome. Neither RBC MTX, RBC folate, nor the RBC MTX:folate ratio identified children at increased risk of failure.

Keywords: Red Blood Cell Methotrexate and Folate, Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

INTRODUCTION

Methotrexate (MTX) is an important component of chemotherapy for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). As a single agent, MTX resulted in remission rates of 29–83%, depending on the dose and route utilized1–2. Today, it is a component of all frontline therapies for children with ALL, given intrathecally, orally, intramuscularly, and/or intravenously. Despite its long history, however, the optimal route and dosage of MTX remain unknown.

After patients achieve remission, leukemic cell exposure to MTX cannot be measured. Therefore surrogate markers of exposure have been evaluated, including plasma MTX levels and red blood cell (RBC) MTX and folate concentrations3–9. Plasma MTX levels correlated with outcome in some studies, but not in others10–13, possibly because these levels do not reflect blast cell exposure/uptake or account for variation in duration of exposure or peak concentration. RBC MTX uptake occurs only during the erythroblast stage of development14, through the same mechanisms utilized by folate. MTX is then polyglutamated15 and retained throughout the life of the RBC. When MTX dosing is unchanged, steady state RBC MTX concentrations are reached after 6–12 weeks3–4. Therefore, RBC MTX concentrations have been studied as a surrogate marker of overall drug exposure and of compliance, absorption and metabolism. The study reported here prospectively sought to determine whether RBC MTX and folate concentrations or steady state plasma MTX levels were related to treatment outcome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

From January 1991 until September 1994, patients with newly diagnosed B-precursor ALL were enrolled on concurrent Pediatric Oncology Group (POG) studies 9005 and 9006 for patients with lower and higher risk of relapse, respectively. Patients were classified at diagnosis as having a lower or higher risk of relapse based on: (1) age, (2) white blood cell count (WBC), (3) DNA index (DNA content in leukemic cells/DNA content of normal cells), (4) presence of central nervous system (CNS) leukemia (blasts present on cytospin with WBC ≥ 5 cells/µL), and (5) presence of testicular disease (Table 1). Patients later found to have the Philadelphia chromosome [t(9;22)] or t(1;19) were classified as being at higher risk of relapse, regardless of other presenting features. Diagnosis was based on morphology and immunohistochemical staining. Lymphoblasts were Sudan black or esterase negative, lacked T-cell associated markers, and were of L1 or L2 FAB morphology or L3 and lacked surface immunoglobulin. Patients who completed intensive continuation (excluding those with t(9;22) and t(4;11)) are included in this analysis. Studies were approved by the institutional review board at each participating center. Informed consent was obtained from patients and parents or legal guardians prior to study enrollment. The follow-up period was to September 1, 2005, when the study data were frozen.

Table 1.

Criteria for Risk Classification

| DNA Index |

CNS or Testicular |

WBC × 103/µL |

Age (years) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 – 2.99 | 3 – 5.99 | 6 – 10.99 | ≥ 11 – 21 | |||

| ≤ 1.161 | Negative | < 10 | A2 | A | A | B3 |

| ≤ 1.16 | Negative | 10–99 | B | A | B | B |

| ≤ 1.16 | Negative | ≥ 100 | B | B | B | B |

| > 1.16 | Negative | Any | A | A | A | A |

| Any | Positive | Any | B | B | B | B |

≤ 1.16 or technically unsatisfactory

A, lower risk for relapse, POG 9005

B, higher risk for relapse, POG 9006

Treatment

The treatment regimens for POG 9005 Regimens A and C and 9006 Regimen A have been previously reported16–17. Each of these regimens included intermediate dose MTX (ID MTX) (1 gram/m2) as a 24 hour infusion every other week for 12 doses during the intensive continuation of treatment. Forty-eight hours after the start of the methotrexate infusion, leucovorin 5 mg/m2 IV/PO was administered every 6 hours × 5 doses or until the plasma methotrexate level was < 0.1 µM. The total duration of therapy was 2.5 years after completion of induction.

CNS negative patients received prophylaxis with 16 and 18 doses of age adjusted triple intrathecal therapy on POG 9005 and 9006, respectively. Patients with CNS leukemia were treated on POG 9006 and received 11 doses of age adjusted intrathecal therapy, followed by radiation therapy (2400 cGy cranial and 1500 cGy spinal) at the completion of intensive continuation. No additional intrathecal therapy was administered after craniospinal radiation. Patients with testicular disease received bilateral testicular radiation.

Initial marrow response was assessed on day 29 of induction. Complete response was defined as ≤ 5% blasts on bone marrow examination with hematologic recovery of peripheral counts and normal physical exam. If 6 – 25% blasts remained on the day 29 marrow, an additional two weeks of induction therapy with vincristine and prednisone was administered. Induction failure was defined as > 25% blasts on day 29 or > 5% blasts on day 43. Bone marrow relapse was defined as >25% marrow blasts. CNS relapse was defined as positive cytomorphology and ≥5 WBC/µl. Bilateral testicular biopsies were required to confirm testicular relapse.

Sample Collection and Processing

Steady state plasma MTX levels were obtained at the end of each 24 hour ID MTX infusion and were assayed at the local institutions. Samples for RBC MTX and folate were drawn at completion of intensive continuation (week 25). Intensive continuation for all regimens included administration of the final ID MTX on day 1 of week 23 with the last MTX administration prior to sample acquisition of 20 mg/m2 intramuscularly on day 1 of week 24. Whole blood was collected into ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) containing tubes. Care was taken to ensure that the vacuum was maintained within the tube. Samples were shipped via regular mail at room temperature to Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas. The methods for RBC MTX and RBC folate assays have been previously published4, 18–20.

Statistical Considerations

There were 1150 patients enrolled on POG 9005 Regimens A and C and POG 9006 Regimen A who lacked t(9;22) and t(4;11). The primary endpoint was continuous complete remission (CCR), and was computed as the time from the completion of intensive continuation to failure (relapse, secondary malignancy, or death) or last contact (non-failures). A Wilcoxon rank sum or Kruskal-Wallis test was used to evaluate the effects of NCI risk group, gender and race on RBC MTX, RBC folate, RBC MTX:folate ratio, median steady state MTX level (median of the 12 institutional post-infusion values). Univariate analyses were conducted to study the association of NCI risk group, DNA index, gender, median steady state MTX level, RBC MTX, RBC folate, and RBCMTX:folate with CCR. Survival curves were computed using the Kaplan-Meier method and the corresponding standard errors was computed using Greenwood’s formula of Kalbfleisch and Prentice21. Results were given as estimate + standard error in this report. Multivariate analysis of the relative prognostic factors for CCR was performed using the Cox regression model22. Stepwise Cox regression was performed using a significance level of 0.05 for both entering and removing explanatory variables from the model.

RESULTS

Of the 1150 patients, 1124 patients completed intensive continuation (26 failures: 12 induction failures, 5 relapses, 5 induction deaths, 3 remission deaths, and 1 other). This report is based on these 1124 patients. Patient characteristics are presented in Table 2. Fifty three percent of patients were male and 71%, 9%, 13%, and 7% of patients self-identified as Caucasian, African-American, Hispanic, or other, respectively. Median age at diagnosis was 4.25 years (range 1.07–20.38). The demographic summary for the entire cohort of 1150 patients was similar to that for the 1124 patients included in this analysis.

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics

| Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 598 | 53 |

| Female | 526 | 47 |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 801 | 71 |

| African-American | 103 | 9 |

| Hispanic | 146 | 13 |

| Other | 74 | 7 |

| NCI risk | ||

| Standard risk | 883 | 79 |

| High risk | 241 | 21 |

| DNA index1 | ||

| ≤ 1.161 | 761 | 69 |

| > 1.161 | 340 | 31 |

| t(1;19) | 36 | 3 |

23 patients did not have DNA index results

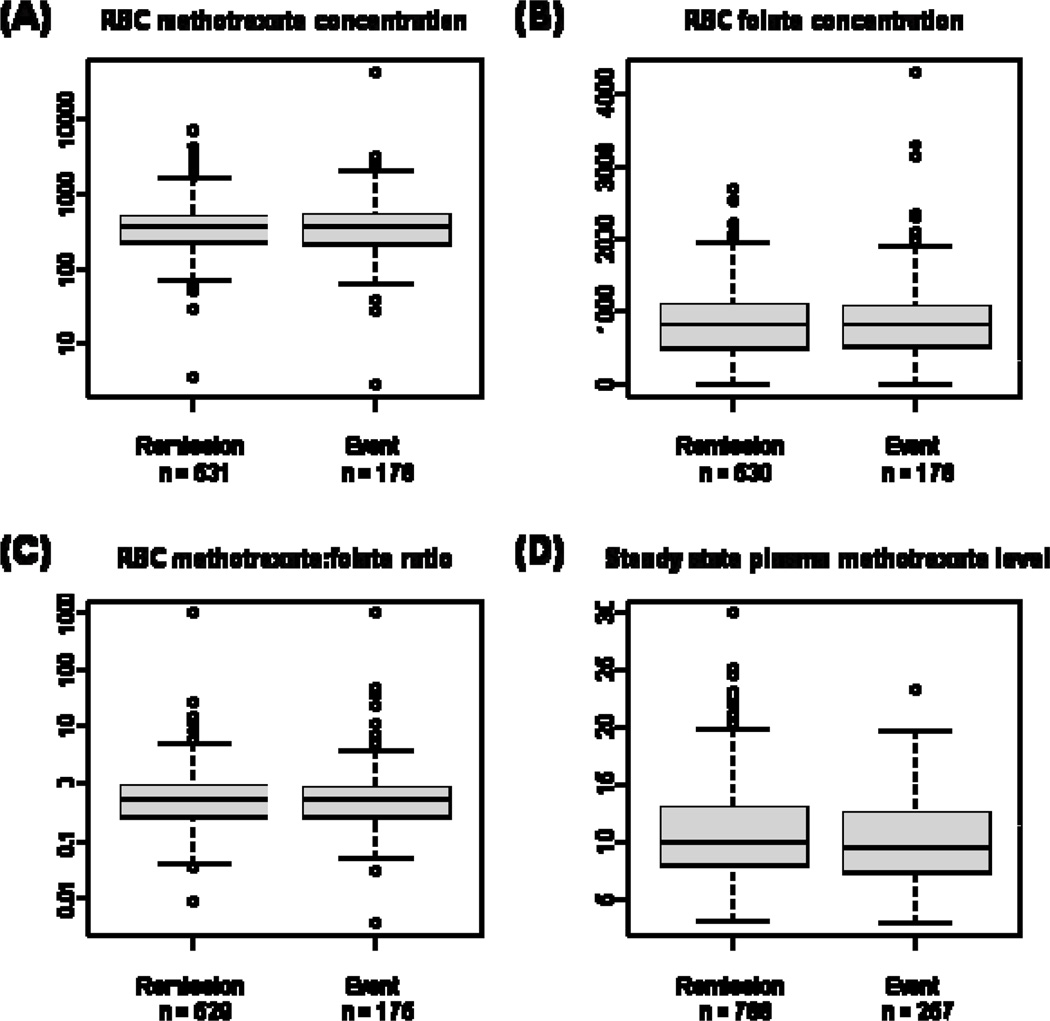

Of the 1124 patients who completed intensive continuation, 286 patients experienced events (Table 3). Direct comparison of the RBC MTX, RBC folate, and RBC MTX:folate ratio with remission status (Figure 1 and Table 4), failed to show significant differences between the remission and event groups. The median steady state MTX levels were 9.93 and 9.45 µM for remission and event groups, respectively, p = 0.0123.

Table 3.

Outcome of Patients Completing Intensive Continuation

| Outcome | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| No Event | 838 (75) |

| Relapse | |

| Isolated Marrow | 149 (13) |

| Isolated CNS | 38 (3) |

| CNS + Other site | 30 (3) |

| Extramedullary ± Marrow | 56 (5) |

| Second Malignancy | 6 (0.5) |

| Remission Death | 7 (0.5) |

| Total | 1124 |

Figure 1.

Box plots of (A) RBC MTX concentration, (B) RBC folate concentration, (C) RBC MTX:folate ratio, and (D) Steady state plasma MTX level (institutional MTX median) for patients in continuous remission versus those who experienced events post-intensive continuation therapy. The box represents the 1st to 3rd quartile (the middle 50% of data), the horizontal line is the median value, the bars represent the range, and the individual points are statistical outliers.

Table 4.

Comparison of patients who had events vs those in remission

| In Remission | Had Event | |

|---|---|---|

| RBC MTX1 | 353.26 (226.78, 510.75)2 | 353.82 (206.96, 537.89) |

| RBC Folate1 | 788.75 (468.32, 1072.89) | 792.94 (486.82, 1051.27) |

| RBC MTX:Folate | 0.47 (0.25, 0.85) | 0.48 (0.24, 0.80) |

| Steady State MTX3 | 9.93 (8.00, 12.85) | 9.45 (7.45, 12.40) |

pmol/ml RBC;

Median (quartiles);

µM

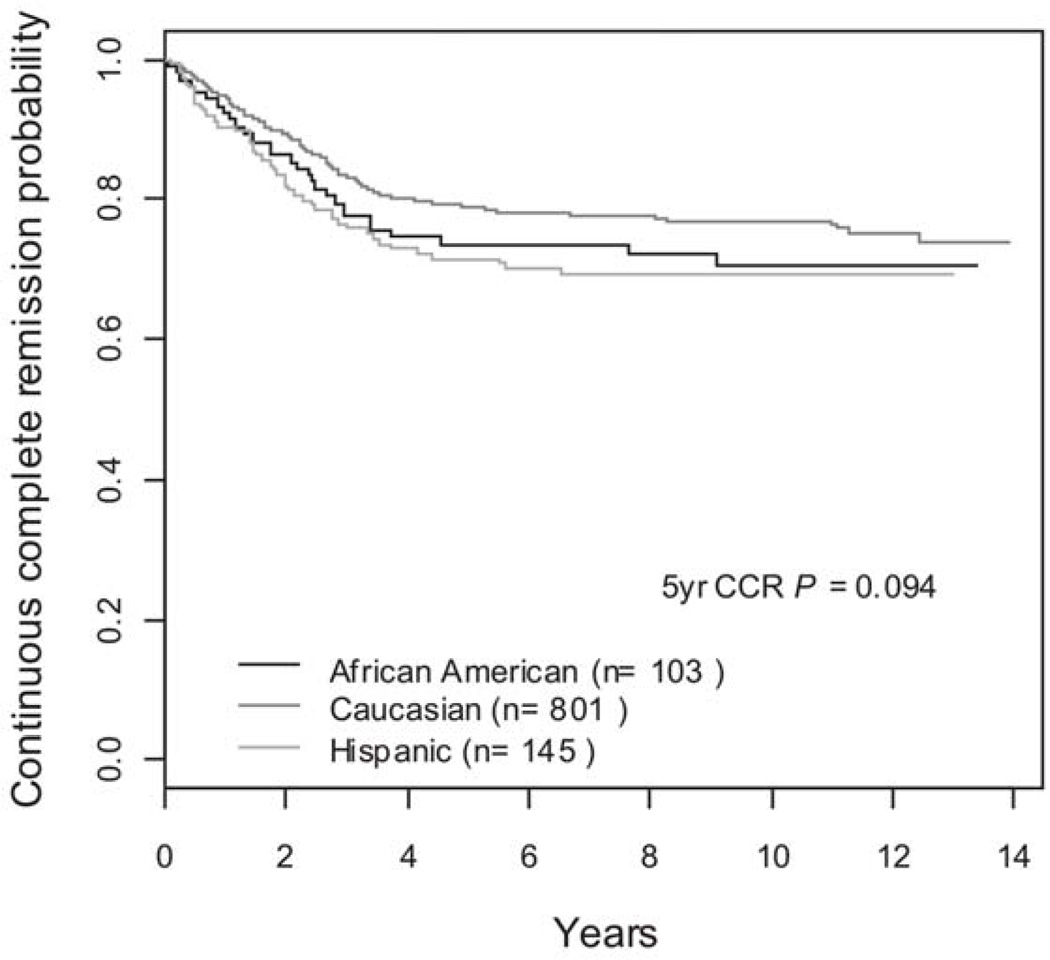

The effects of NCI risk group, gender, and race on RBC MTX, RBC folate, RBC MTX:folate ratio and median steady state MTX level are shown in Tables 5 and 6. Gender and NCI risk group did not result in a significant difference in values for any of the measured parameters. Race did not result in a significant difference in values for RBC MTX, RBC folate, or RBC MTX:folate ratio. Hispanic children had significantly lower median steady state plasma MTX levels (8.70 µM vs. 9.95 µM; p = 0.0015), but similar outcomes with five year CCR rates of 72 ± 3.8%, 79 ± 1.4%, and 74 ± 4.4% for Hispanic, Caucasian, and African American children, respectively (p=0.09), Figure 2.

Table 5.

Effect of NCI Risk Group and Gender on RBC MTX, RBC Folate, and Plasma MTX Values

| NCI Risk Group | Gender | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard | High | p | Male | Female | p | |

| RBC MTX1 | 359 (225,500)2 | 344 (222,537) | 0.86 | 370 (248,528) | 341 (202,497) | 0.10 |

| RBC Folate1 | 766 (459,1057) | 870 (570,1137) | 0.09 | 785 (509,1067) | 794 (445,1081) | 0.81 |

| RBC MTX:Folate | 0.49 (0.25,0.87) | 0.44 (0.24,0.76) | 0.24 | 0.49 (0.26,0.80) | 0.44 (0.24,0.89) | 0.49 |

| Steady State MTX3 | 9.8 (7.9,12.5) | 10.0 (7.8,13.0) | 0.38 | 9.9 (7.9, 12.5) | 9.8 (7.9, 13.0) | 0.83 |

pmol/ml RBC;

Median (quartiles);

µM

Table 6.

Effect of Race on RBC MTX, RBC Folate, and Plasma MTX Values

| Caucasian | Hispanic | African American | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBC MTX1 | 353(222,512)2 | 348(202,497) | 380(235,548) | 0.63 |

| RBC Folate1 | 798(476,1071) | 850(482,1229) | 761(475,1033) | 0.63 |

| RBC MTX:Folate | 0.49(0.25,0.86) | 0.41(0.21,0.81) | 0.48(0.26,0.85) | 0.51 |

| Steady State MTX3 | 9.9(8.1,12.9) | 8.7(7.5,12.0) | 10.1(7.9,12.4) | 0.006 |

pmol/ml RBC;

Median (quartiles);

µM

Figure 2.

Five year CCR in Hispanic, Caucasian, and African American Children

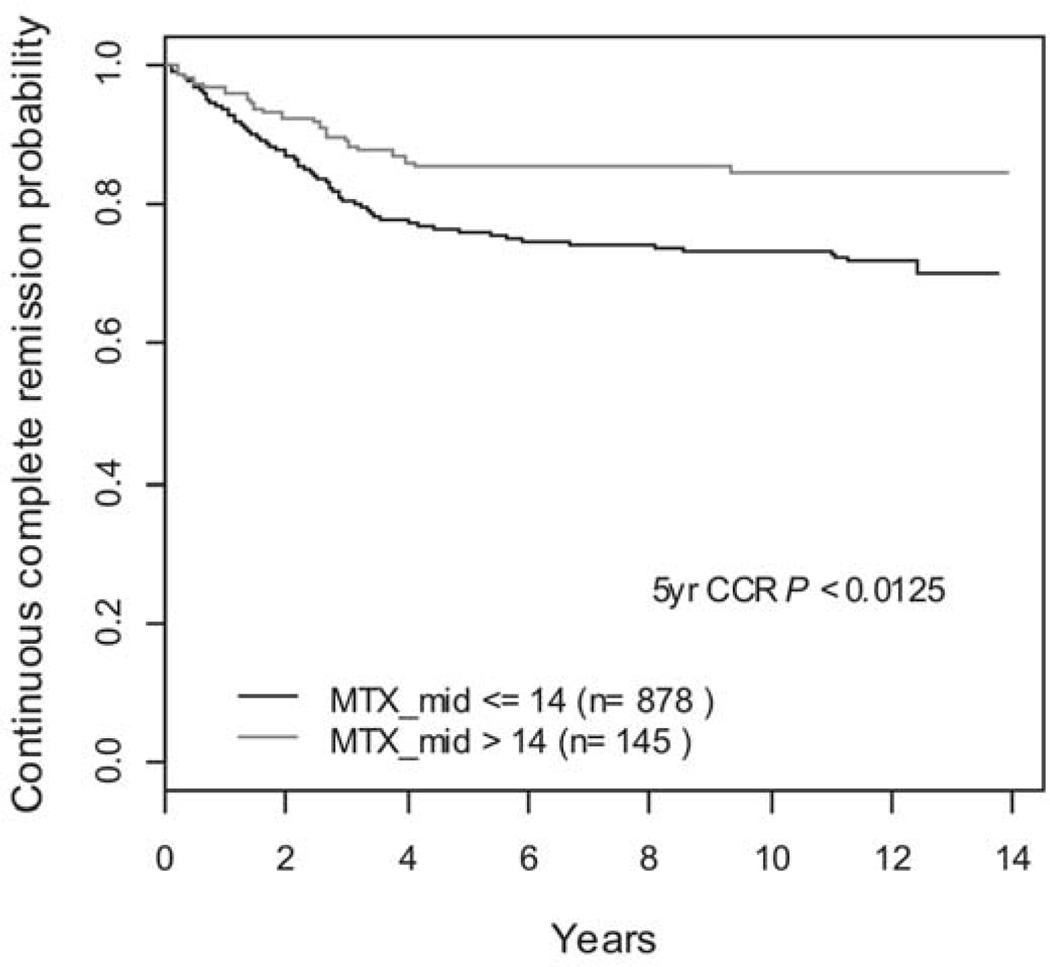

The univariate analyses of the association of NCI risk group, DNA index, gender, and median steady state MTX level, RBC MTX, RBC folate, and RBCMTX:folate with CCR revealed significant associations with NCI risk (p < 0.0001), DNA index (p = 0.0025), Gender (p = 0.0031), median steady state MTX level (p = 0.0126), and non-significant associations with RBC folate (p = 0.7365), RBC MTX (p = 0.1284) and RBC MTX:folate ratio (p = 0.1512). The receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves 23 were utilized to discriminate the effect of MTX level on CCR. The optimal cutoff of MTX level was 14 µM and the univariate analyses of the association of the dichotomized median steady state MTX level with CCR revealed a p-value of 0.0051 at the cutoff of 14 µM. The five-year CCR was 76 ± 1.4% versus 85 ± 3.0% for those patients with median steady state MTX levels ≤ and > 14 µM, respectively (p=0.0125), Figure 3. When analyzed by risk group, patients with lower risk of relapse had a trend towards improved outcome with a five-year CCR of 79 ± 1.5% versus 86 ± 3.3% for those with median steady state MTX levels ≤ and > 14 µM, respectively, but this did not reach statistical significance (p=0.1089). However, patients with higher risk of relapse had a five-year CCR of 64 ± 3.6% versus 84 ± 6.5% for those with median steady state MTX levels ≤ and > 14 µM, respectively (p=0.0231).

Figure 3.

Five year CCR in Patients with Steady State MTX levels ≤ 14 µM and > 14 µM

In the first Cox regression analysis, the relative prognostic importance of NCI risk group, DNA index, gender, and dichotomized median steady state MTX level were evaluated in the 1005 patients with complete data. The rank order of significance of each of the factors in the Cox regression was: (1) NCI risk group (p<0.001), (2) gender (p=0.004), (3) dichotomized median steady state MTX level (p=0.006), and (4) DNA index (p=0.007). Patients with median steady state MTX levels ≤ 14 µM (for a given NCI risk group, DNA index, and gender) had an increased instantaneous risk of failure of 1.84 (95% confidence interval, 1.19–2.84) relative to those with median steady state MTX levels > 14 µM.

In the second Cox regression analysis, the relative prognostic influence of NCI risk group, DNA index, gender, RBC MTX, RBC folate, and RBC MTX:folate ratio on CCR were evaluated in the 690 patients with complete data. Only NCI risk group reached significance (p=0.005). After adjustment for NCI risk group, the RBC MTX concentration was closest to significance (p=0.066).

DISCUSSION

MTX is an integral component of therapy for childhood ALL, but the optimal dosing schedule remains unknown. MTX has been administered in a wide range of dosages from 20 mg/m2/week by mouth during maintenance therapy to 33.6 grams/m2 intravenously over 24 hours during consolidation24. An intermediate dose of 1 gram/m2 infusion over 24 hours every other week for 12 doses was chosen for the POG 9005/9006 based on pharmacological studies demonstrating that ID MTX infusions were capable of sustaining plasma MTX levels of approximately 7–10 µM (believed to be cytocidal for leukemic cells)25–27. Twenty-four hour infusions of MTX bypassed the considerable variability in plasma drug levels following oral schedules and allowed increased time of exposure to the drug. Plasma concentrations at the end of the infusion and red cell folate and MTX concentrations were collected and analyzed so as to determine if they would serve as surrogate markers of leukemic blast MTX exposure and if they would correlate with CCR.

Higher plasma MTX levels and increased systemic clearance have correlated with a decreased risk of relapse11, 13, 28, though significant intrapatient variability may impact analyses12. Investigators at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital previously reported that steady state plasma MTX levels > 16 µM correlated with decreased risk of relapse, and the present study containing over 1000 patients demonstrated that median steady state plasma MTX levels > 14 µM correlated with decreased risk of relapse. Consistent with the study conducted at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, the plasma MTX level remained statistically significant for outcome only in higher risk patients29. Although this did not reach statistical significance, there was a trend towards improved CCR in patients with lower risk of relapse and steady state plasma MTX levels > 14 µM in our study. The differences in steady state MTX cutoff may be attributed to variation in patient characteristics, schedule of administration of MTX, or concomitant chemotherapy agents. Specifically, questions have been raised as to the role of leucovorin in modulating the safety and efficacy of methotrexate. Early preclinical studies utilizing leucovorin rescue in a mouse model of leukemia demonstrated the difficulty associated with the delivery of an anti-folate and a reduced folate rescue. Specifically, excessive delay or the use of “low doses” of leucovorin were associated with toxic deaths while large doses of leucovorin or the delivery of rescue shortly after the completion of MTX therapy interfered with efficacy30–31. Clinically, Skarby et al32 found that higher doses of leucovorin, despite their correlation with higher plasma MTX concentrations, were associated with an increased risk of relapse and Sterba et al33 found that leucovorin modulates the biologic impact of MTX with a fall in the area under the curve for plasma homocysteine concentrations with successive courses of MTX in response to a leucovorin mediated increase in plasma folate concentrations. In contrast, successful therapies developed by investigators at St Jude Childrens Research Hospital include early leucovorin dosing at hour 36 after the delivery of intrathecal methotrexate, emphasizing the complexities in understanding the impact of leucovorin and methotrexate on outcome in multi-agent trials. It is not known if a change in the dose or schedule of leucovorin delivery would have had a significant impact on the outcome of this trial.

Although Hispanic patients had significantly lower steady state MTX levels, this did not correlate with outcome, nor were these lower MTX levels clinically significant. It should be noted that this subset analysis was not in the original study design or power calculations. Additionally, the accuracy of self-reported ethnicity has been brought into question based upon results of genetic ancestry determined by genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphisms. In a genetic ancestry study of pediatric ALL patients from the Children’s Oncology Group and St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, American Indians as identified by genetic ancestry analysis often self-reported as having Hispanic ethnicity. This cohort of American Indians had a significantly increased risk of relapse34. Further understanding of genetic ancestry may improve our ability to correlate outcome data with ethnicity.

A recent study of pediatric ALL patients from the Children’s Oncology Group and St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital demonstrated an association between germline single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and end induction minimal residual disease (MRD)35. This study identified 102 SNPs associated with MRD, 21 of which were also associated with drug metabolism. Fourteen of these SNPs were associated with either MTX clearance or accumulation of polyglutamates. Three of the SNPs associated with MTX metabolism were also associated with etoposide clearance. This suggests that SNPs that affect MTX metabolism may also affect the metabolism of other chemotherapeutic agents. It is possible that plasma MTX concentrations obtained on the current study may simply be a surrogate of altered metabolism of other chemotherapeutic agents.

RBC MTX concentration may parallel the cellular uptake and polyglutamation of MTX in lymphoblasts. RBC MTX and folate concentrations were monitored before and during treatment on the POG 8036 pilot. A weak correlation between improved CCR and higher RBC MTX concentrations after consolidation was observed4. However, the present study failed to detect correlations between CCR and RBC MTX, RBC folate, or RBC MTX:folate concentrations, indicating that these parameters could not prospectively identify patients at higher risk of an event. These data suggest that RBC concentrations may not be an accurate surrogate for blast cell MTX or folate status during consolidation. It may, however, be more critical during the maintenance phase of therapy where both compliance and metabolism are of greater concern due to chronic administration of low dose oral therapy. Clearly, killing of lymphoblasts by MTX is dependent on factors beyond MTX or MTX:folate concentrations such folylpolyglutamate synthetase, dihydrofolate reductase, and thymidylate synthetase activity, endogenous folate pools and many other factors.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH U10 grant CA98543-08 and CA29139. A complete listing of grant support for research conducted by CCG and POG before initiation of the COG grant in 2003 is available online at: http://www.childrensoncologygroup.org/admin/grantinfo.htm

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the author(s) and are not to be construed as the official policy or position of the U.S. Government, the Department of Defense, or the Department of the Air Force.

REFERENCES

- 1.Perrin JC, Mauer AM, Sterling TD. Intravenous methotrexate (amethopterin) therapy in the treatment of acute leukemia. Pediatrics. 1963;31:833–839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frei E, III, Freireich EJ, Gehan E, et al. Studies of Sequential and Combination Antimetabolite Therapy in Acute Leukemia: 6-Mercaptopurine and Methotrexate. Blood. 1961;18:431–454. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schrøder H, Clausen N, Ostergaard E, et al. Pharmacokinetics of erythrocyte methotrexate in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia during maintenance treatment. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology. 1986;16:190–193. doi: 10.1007/BF00256175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graham ML, Shuster JJ, Kamen BA, et al. Red blood cell methotrexate and folate levels in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia undergoing therapy: a Pediatric Oncology Group pilot study. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1992;31:217–222. doi: 10.1007/BF00685551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graham ML, Shuster JJ, Kamen BA, et al. Changes in red blood cell methotrexate pharmacology and their impact on outcome when cytarabine is infused with methotrexate in the treatment of acute lymphocytic leukemia in children: a pediatric oncology group study. Clin Cancer Res. 1996;2:331–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cole PD, Zebala JA, Alcaraz MJ, et al. Pharmacodynamic properties of methotrexate and Aminotrexate during weekly therapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2006;57:826–834. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0115-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vijayanathan V, Smith AK, Zebala JA, et al. High-performance liquid chromatography separation of aminopterin-polyglutamates within red blood cells of children treated for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Transl Res. 2007;150:367–373. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamen BA, Holcenberg JS, Turo K, et al. Methotrexate and folate content of erythrocytes in patients receiving oral vs intramuscular therapy with methotrexate. The Journal of pediatrics. 1984;104:131–133. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(84)80610-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamen BA, Nylen PA, Camitta BM, et al. Methotrexate accumulation and folate depletion in cells as a possible mechanism of chronic toxicity to the drug. British Journal of Haematology. 1981;49:355–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1981.tb07237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balis FM, Holcenberg JS, Poplack DG, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oral methotrexate and mercaptopurine in children with lower risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a joint children's cancer group and pediatric oncology branch study. Blood. 1998;92:3569–3577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans WE, Abromowitch M, Crom WR, et al. Clinical pharmacodynamic studies of high-dose methotrexate in acute lymphocytic leukemia. NCI Monogr. 1987;5:81–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seidel H, Nygaard R, Moe PJ, et al. On the prognostic value of systemic methotrexate clearance in childhood acute lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Res. 1997;21:429–434. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(96)00127-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Camitta B, Mahoney D, Leventhal B, et al. Intensive intravenous methotrexate and mercaptopurine treatment of higher-risk non-T, non-B acute lymphocytic leukemia: A Pediatric Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:1383–1389. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.7.1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.da Costa M, Iqbal MP. The transport and accumulation of methotrexate in human erythrocytes. Cancer. 1981;48:2427–2432. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19811201)48:11<2427::aid-cncr2820481115>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baugh CM, Krumdieck CL, Nair MG. Polygammaglutamyl metabolites of methotrexate. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1973;52:27–34. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(73)90949-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahoney DH, Jr, Shuster JJ, Nitschke R, et al. Acute neurotoxicity in children with B-precursor acute lymphoid leukemia: an association with intermediate-dose intravenous methotrexate and intrathecal triple therapy--a Pediatric Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1712–1722. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.5.1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lauer SJ, Shuster JJ, Mahoney DH, Jr, et al. A comparison of early intensive methotrexate/mercaptopurine with early intensive alternating combination chemotherapy for high-risk B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a Pediatric Oncology Group phase III randomized trial. Leukemia. 2001;15:1038–1045. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamen BA, Caston JD. Direct radiochemical assay for serum folate: competition between 3H-folic acid and 5-methyltetrahydrofolic acid for a folate binder. The Journal of laboratory and clinical medicine. 1974;83:164–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamen BA, Takach PL, Vatev R, et al. A rapid, radiochemical-ligand binding assay for methotrexate. Analytical biochemistry. 1976;70:54–63. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(76)80047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamen BA, Caston JD. Properties of a folate binding protein (FBP) isolated from porcine kidney. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1986;35:2323–2329. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(86)90458-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalbfleisch JD, Prentice RL. The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc/; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cox DR. Regression models and Life-Tables. Journal of Royal Statistical Society. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patrick J, Thomas L, Margaret S. Time-Dependent ROC curves for censored survival data and a diagnostic marker. Biometrics. 2000:337–344. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hilden JM, Dinndorf PA, Meerbaum SO, et al. Analysis of prognostic factors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in infants: report on CCG 1953 from the Children's Oncology Group. Blood. 2006;108:441–451. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-3011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keefe DA, Capizzi RL, Rudnick SA. Methotrexate Cytotoxicity for L5178Y/Asn- Lymphoblasts: Relationship of Dose and Duration of Exposure to Tumor Cell Viability. Cancer Res. 1982;42:1641–1645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borsi JD, Moe PJ. A comparative study on the pharmacokinetics of methotrexate in a dose range of 0.5 g to 33.6 g/m2 in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer. 1987;60:5–13. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870701)60:1<5::aid-cncr2820600103>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodman JH, Sunderland M, Kavanagh RL, et al. Pharmacokinetics of Continuous Infusion of Methotrexate and Teniposide in Pediatric Cancer Patients. Cancer Res. 1990;50:4267–4271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Evans WE, Crom WR, Abromowitch M, et al. Clinical pharmacodynamics of high-dose methotrexate in acute lymphocytic leukemia. Identification of a relation between concentration and effect. New England Journal of Medicine. 1986;314:471–477. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198602203140803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evans WE, Schell MJ, Pui CH. MTX clearance is more important for intermediate-risk ALL. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:1115–1116. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.6.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sirotnak FM, Donsbach RC, Moccio DM, et al. Biochemical and pharmacokinetic effects of leucovorin after high-dose methotrexate in a murine leukemia model. Cancer Res. 1976;36:4679–4686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sirotnak FM, Moccio DM, Dorick DM. Optimization of high-dose methotrexate with leucovorin rescue therapy in the L1210 leukemia and sarcoma 180 murine tumor models. Cancer Res. 1978;38:345–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skarby TVC, Anderson H, Heldrup J, et al. High leucovorin doses during high-dose methotrexate treatment may reduce the cure rate in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2006;20:1955–1962. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sterba J, Dusek L, Demlova R, et al. Pretreatment Plasma Folate Modulates the Pharmacodynamic Effect of High-Dose Methotrexate in Children with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia and Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma:"Folate Overrescue" Concept Revisited. Clin Chem. 2006;52:692–700. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.061150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harvey RC, Mullighan CG, Wang X, et al. Identification of novel cluster groups in pediatric high-risk B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia with gene expression profiling: correlation with genome-wide DNA copy number alterations, clinical characteristics, and outcome. Blood. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-239681. Epub 2010 Aug 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang JJ, Cheng C, Yang W, et al. Genome-wide Interrogation of Germline Genetic Variation Associated With Treatment Response in Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Jama. 2009;301:393–403. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]